Introduction

A characteristic feature of epithelial cancer is

aberrant glycosylation of glycoproteins. The Tn antigen, an

O-linked N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) epitope, which should be

covered by other distal sugars in normal cells, is a well

characterized glyco-epitope expressed by breast, colorectal and

ovarian cancer cells (1–8).

MUC1 is a 500–1000-kDa transmembrane glycoprotein

expressed by normal and cancer cells. In healthy human epithelial

cells MUC1 is expressed on the apical surface of the cell, i.e.,

the side of the cell membrane that faces the tubular interior of a

vessel. As a mucin, its functions are to lubricate, to keep the

cell hydrated, and to protect from pathogen invasion. The

extracellular domain of MUC1 contains a variable number (25–125) of

tandem repeats of 20 amino acids in length (1–8),

each of which has five potential O-glycosylation sites:

(-His-Gly-Val-Thr-Ser-Ala-Pro-Asp-Thr-Arg-Pro-Ala-Pro-Gly-Ser-Thr-Ala-Pro-Pro-Ala-)n.

In healthy cells, MUC1 is heavily glycosylated, and the O-glycans

are mostly of the core 2 type, which is a trisaccharide. It may be

elongated by several LacNAc units, whereas fucose and/or sialic

acid are terminal sugars of the completed oligosaccharide. Unlike

normal cells, most carcinomas overexpress MUC1, and MUC1 is

distributed over the entire cell surface. The glycans are

‘abnormal’ due to incomplete glycosylation and premature

sialylation. Two common tumor associated antigens found in

carcinomas are the Tn (αGalNAc, 2), and the STn

(αNeuAc-2,6-αGalNAc). It is believed that these glycans are

truncated because there are different expression levels of glycosyl

transferases in carcinomas when compared to healthy cells, which

may be caused by mutation or inactivation of glycosyltransfeases,

or by lack of functional chaperone proteins for

glycosyltransferases. The mutation of COSMC, an X chromosome

located gene encoding a chaperon protein required by core-1

β1,3-galactosyltransferase, is believed to be associated with

expression of the Tn antigen (9).

Due to the overexpression of MUC1 by almost all epithelial

carcinomas, glycopeptide partial sequences with abnormal O-glycans

contained in the MUC1’s tandem repeats are ideal potential antigens

and biomarkers that could be detected by monoclonal antibodies.

A fundamental problem is that the exact epitopes at

the molecular level remain unknown. If and how epitope expression

changes over time as the cancer progresses is also poorly

understood (10). One could

envision isolating MUC1 glycopeptides directly from cancer cells,

and analyzing them by mass spectrometry. However, a major obstacle

is the resistance of MUC1 toward proteolytic digestion. Two methods

that have been used for the discovery or detection of MUC1 epitopes

both take advantage of glycostructure recognition by antibodies.

The first method utilizes synthetic glycopeptides believed to exist

on cancer MUC1, conjugation of these glycopeptides to create an

immunogen, immunization of mice (11), collection of anti-sera, and

analysis of the binding of antibodies to MUC1 expressed on cancer

cells by flow cytometry (FACS) analysis (12). The advantage of this method is that

polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies can be obtained that recognize

an epitope of known chemical structure, and using these antibodies,

cancer tissue can be analyzed for the presence of a particular

epitope. However, the obtained antibodies can only detect the

epitope for which they were elicited, and the presence of other

epitopes may remain undetected. The second approach utilizes modern

glyco-microarrays (13), which are

utilized for the screening of patient serum for the presence of

auto-antibodies that recognize compounds in the microarray. While

this approach is capable of detecting multiple epitopes given that

the patient has produced auto-antibodies, large micro-arrays are

required, and not every patient produces sufficient levels of

auto-antibodies against MUC1. Thus, cancer may not be detected in

all patients due to an insufficient diversity of the microarray, or

due to no (or weak) immune responses to the cancer. While large

glyco-microarrays have been printed, including glycopeptides of

MUC1, undoubtedly even more diverse glyco-microarrays are needed

for the discovery of new biomarkers using the screening

methodologies already in place. There are currently no tools

available that allow for a comprehensive screening of cancer tissue

for the presence of a large number of specific biomarkers.

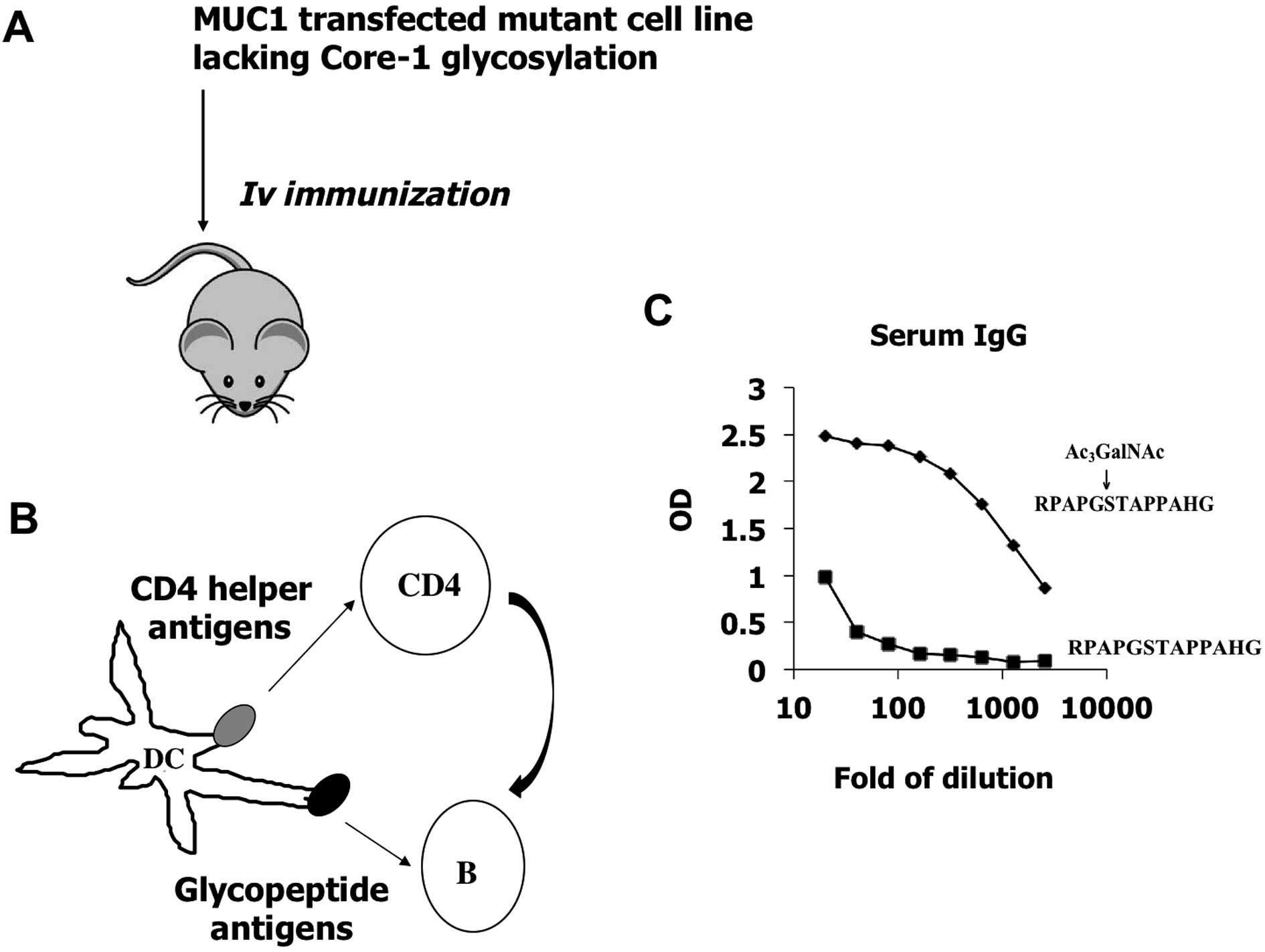

In this study, we generated glycopeptide-specific

antibodies which recognize authentic glycoforms expressed by tumor

cells (Fig. 1). The method will

allow us to generate a library of monoclonal antibodies that

recognize all existing forms of glycopeptides abnormally expressed

by tumor cells deficient in O-glycosylation, which may lead to

feasible methods to study the O-linked glycoproteome in cancer

cells.

Materials and methods

Predicting glycopeptide sequences by

computational glycomics

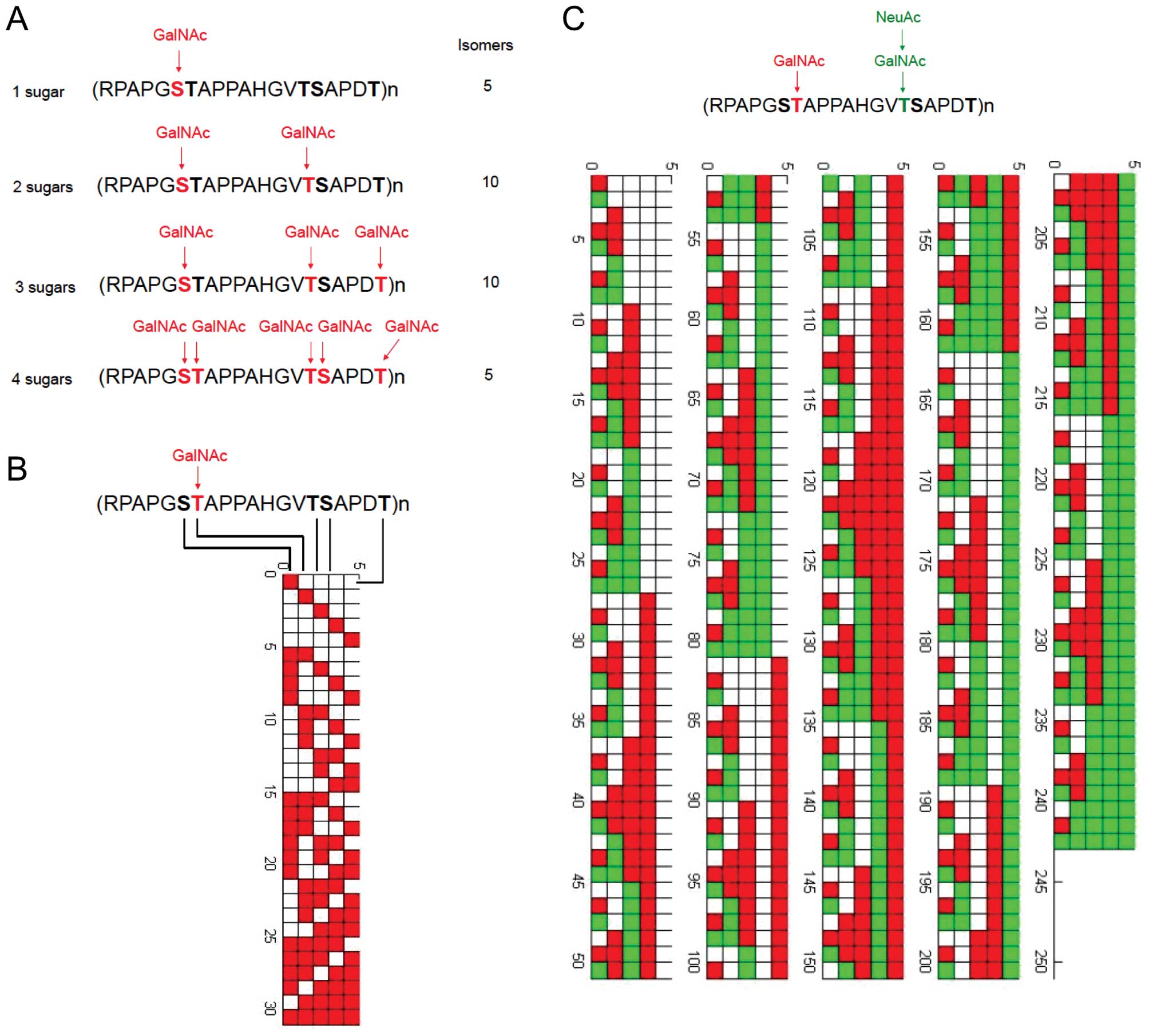

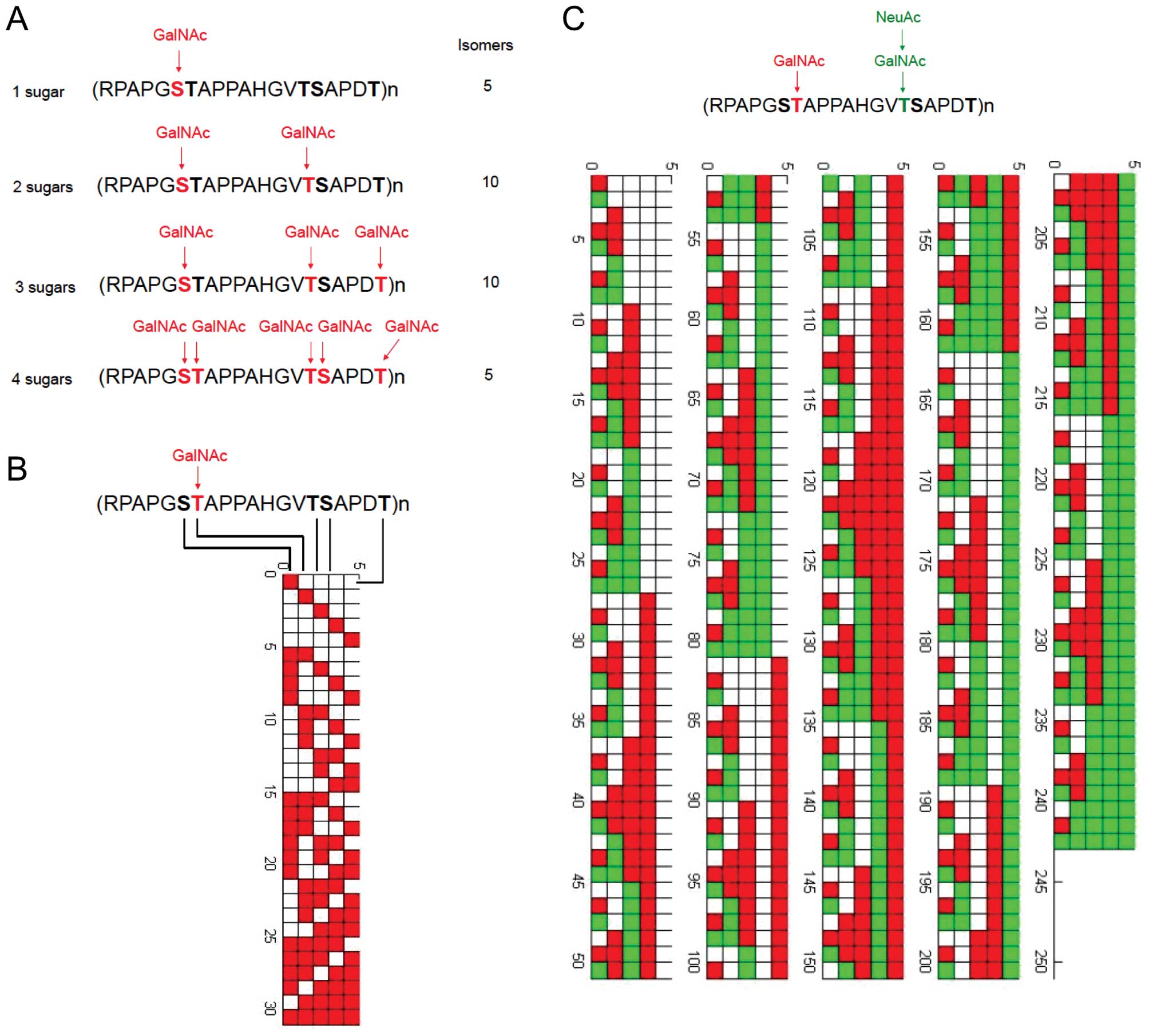

We have analyzed the family of mucin glycoproteins,

focusing on tandem repeat sequences which are heavily

O-glycosylated, and express Tn antigens in cancer conditions. A

theoretical database covering possible O-glycopepetide sequences

has been constructed by MATLAB language. Fig. 2 shows the example of MUC1 tandem

repeat modified by Tn antigen (GalNAc) and sialyl Tn antigen

(NeuAcα6GalNAc).

| Figure 2Theoretical glycopeptide epitopes

expressed by MUC1. (A) MUC1 protein is heavily glycosylated in the

tandem repeat domain of 20 amino acids. Each TR domain contains 5

potential O-glycosylation sites. We have generated a database of

glycopeptide sequences with 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 GalNAc residues,

respectively. Of 31 possible MUC1 glycopeptides that vary in number

and location of Tn epitopes, four MUC1 sequences that bear one,

two, three, or four Tn moieties are illustrated. For TR domain

which may bear 1 GalNAc residue, there may exist 5 different

isomers for antibody recognition. For TR domain which bears 2

GalNAc residues, there may exist 10 different isomers for antibody

recognition. For TR domain which bears 3 GalNAc residues, there may

exist 10 different isomers for antibody recognition. For TR domain

which bears 4 GalNAc residues, there may exist 5 different isomers

for antibody recognition. In reality, cross-reactivity must be

considered for monoclonal antibody recognition, thus the exact

number of epitopes which may be uniquely recognized by monoclonal

antibodies must be determined by experiments. (B) All possible

modification results by GalNAc sugar (31 results in total) in a

single sequence of RPAPGSTAPPAHGVTSAPDT, as constructed by MATLAB

language. (C) All possible modification results (242 results in

total) by GalNAc and NeuAc sugars in a single sequence of

RPAPGSTAPPAHGVTSAPDT. |

In a MATLAB program specially designed to create

Fig. 2B, each of the five

modifiable loci was represented by binary digits. After simple

calculation, a 5x31 matrix with all zeros was created. Functions

existing in MATLAB were utilized to change zeros to ones in the

matrix sequentially. Each element of zero represents a locus

without modification, while one represents a locus with

modification of GalNAc. Finally, every element in the matrix was

inputed into a loop, creating a figure where X-axis is five

rectangles representing five loci in (RPAPGSTAPPAHGVTSAPDT)n and

Y-axis is different modification results (each modified locus was

stained by red color).

Based on the same principle, Fig. 2C was created, ternary digits were

utilized to represent different modification. Loci with

modification of GalNAc only was stained by red color. The

combination of GalNAc and NeuAc was stained by green color.

Biotinylated (glyco)peptides

The biotinylated glycopeptide

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG-dPEG™11-Biotin (Fig. 3), and non-glycosylated peptide,

RPAPGTAPPAHG-dPEG™11-Biotin were custom synthesized by Peptide

International Inc. (Louisville, KY). They were synthesized on an

automated peptide synthesizer from Protein Technologies, Inc.

(Tucson, AZ), model ‘Prelude’, using fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl

(Fmoc)-protected amino acids as the building blocks,

6-chloro-benzotriazole-1-yl-oxy-tris-pyrrolidino-phosphonium

hexafluorophosphate (PyClock) as the coupling reagent, and

2-chlorotrityl resin preloaded with glycine, loading capacity 0.59

mmol/g, as the solid support. In each coupling cycle PyClock and

the Fmoc amino acid were used in 2.5-fold excess, and

N-methylmorpholine (NMM) in 4.25-fold excess in

N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Removal of the Fmoc group after each

coupling was performed with 20% piperidine in DMF. For the

glycopeptide preparation, the glycosylamino acid

Fmoc-Thr(Ac3GalNAc)-OH was coupled in only 1.2-fold

excess with the coupling reagent

O-(7-Azabenzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium

hexafluorophosphate (HATU) and NMM. The peptide and glycopeptide

were released from the resin with simultaneous deprotection by

treatment with cocktail R (TFA/thioanisole/EDT/anisole, 90:5:3:2)

and precipitated by cold ether. The crude peptides were purified by

preparative reversed-phase HPLC. The peptides were biotinylated via

the heterobifunctional cross linker

mono-N-t-Boc-amido-dPEG®11 amine. Coupling was performed

with diphenylphosphoryl azide and NMP in solution. Peptides were

characterized by mass spectrometry.

The glycopeptide

RPAPGS(GalNAc)TAPPAHG-dPEG™11-Biotin was prepared by deacetylation

of RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc) TAPPAHG-dPEG™11-Biotin. Briefly,

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc) TAPPAHG-dPEG™11-Biotin (600 μg

in 100 μl DMSO solution) was mixed with 5 μl

hydrazine. The mixture was shaken at room temperature for 30 min.

The deacetylation reaction was monitored by analytical HPLC on a

Waters 626 HPLC instrument with a Symmetry300™ C18 column (5.0

μm, 4.6x250 mm) at 40°C, eluted with a linear gradient of

0–60% MeCN containing 0.1% TFA within 20 min at a flow rate of 1

ml/min. Preparative HPLC was performed on a Waters 600 HPLC

instrument with a preparative Symmetry300 C18 column (particle size

7.0 μm, dimensions 19x250 mm), which were eluted with a

suitable gradient of aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% TFA at a

flow rate of 12 ml/min. The residue was neutralized with AcOH until

pH 4.0, and subject to the preparative HPLC purification to give

the de-acetylated product (420 μg as quantified by

analytical HPLC).

The glycopeptide containing the tri-O-acetylated

GalNAc residue (synthetic precursor of the de-O-acetylated

glycopeptide, RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG-dPEG™11-Biotin)

was included in the binding studies in order to answer the question

whether OH-3, OH-4, and OH-6 of the GalNAc residue were important

for the binding specificity of the mAbs. ELISA experiments with the

non-glycosylated peptide allows for clues of the extent of peptide

involvement in binding.

Mass spectrometry analysis of

(glyco)peptides

Glycosylated and non-glycosylated peptides were

diluted in 80% ACN/0.1% FA to a final concentration of 0.1

μg/μl and 1 μl was directly injected at 300

nl/min into an ESI-linear ion trap-mass spectrometer (LTQ XL,

Thermo-Fisher Scientific), equipped at the front end with a

nano-electrospray ionization source (Thermo-Fisher Scientific). MS

spectra were collected in positive-ion mode for 120 sec, at the

400–2,000 m/z range, and the ions of interest were subjected to

collision-induced dissociation (35% normalized collision

energy).

Generation of a monoclonal antibody

specific for RPAPGS-(GalNAc)TAPPAHG

cDNA containing MUC1 tandem repeat sequences was

generated from the breast cancer cell line T47D by a RT-PCR kit

from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), with PCR primers

5′-atgacaccgggcacccagtctcct-3′ and 5′-tcaggggagcatggggaaggaaaag-3′.

The amplified cDNA sequence was compared to published literature

(8, GenBank: X52228.1), and cloned into vector pcDNA-IRES-eGFP

(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The Jurkat cell line, which synthesizes

abnormal glycans (O-GalNAc residue) on all glycoproteins (14), was transfected by

pcDNA-IRES-eGFP-MUC1 and the mock vector pcDNA-IRES-eGFP,

respectively. Stable cell lines were generated by selection with

G418, and fluorescence-activated cell sorting for eGFP expressing

cells. C57B6 mice were immunized by Jurkat pcDNA-IRES-eGFP-MUC1.

Monoclonal antibodies were generated by screening against each

synthesized glycopeptide using ELISA methods as described below.

One monoclonal antibody, 16A, has been generated, which showed

stronger binding to RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG in ELISA

experiments than the non-glycosylated RPAPGSTAPPAHG. Another

monoclonal antibody, 14A, which showed similar binding to

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG and RPAPGSTAPPAHG, was also

generated.

ELISA to determine antibody binding to

glycopeptides

The biotinylated (glyco)-peptides (1 μg/ml)

were bound to streptavidin-coated plates (2 μg/ml), and

incubated with serially diluted serum for 2 h. Binding of

glycopeptide-specific IgG was visualized by a secondary antibody

(goat anti-mouse IgG) followed by colorimetric detection. One

percent bovine serum albumin was used as blank for determining the

cutoff value.

Immunohistochemistry

The study subjects were female patients selected

from a clinical database at the University of Texas M.D. Anderson

Cancer Center. The institutional review boards (IRB) of the M.D.

Anderson Cancer Center approved the retrospective review of the

medical records and identification and analysis of tumor blocks for

the purposes of the present study. Breast cancer diagnosis was made

by core needle or excisional biopsy of the breast tumor. All

pathologic specimens were reviewed by dedicated breast

pathologists. The histological type of the tumor specimens was

defined according to the World Health Organization Classification

System (15).

Immunohistochemistry was performed as previously

described (16). Briefly,

5-μm paraffin-fixed tissue sections were deparaffinized in

xylene and rehydrated through using a gradient of alcohol (100, 95

to 80%, Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Antigen retrieval was carried out

for 30 min using PT Module (Lab Vision Corp., USA) in Tris-EDTA

buffer (pH 9.0). After cooling down, the slides were thoroughly

washed in distilled water and washed three times in 1X

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), 2 min each. Endogenous peroxidase

activity was quenched by immersion in 3% hydrogen peroxide (Sigma),

then in methanol for 10 min at room temperature followed by rinsing

for 2 min in 1X PBS three times. Nonspecific binding of the primary

antibody was blocked by incubating the sections with 10% normal

horse serum for 30 min at room temperature. Sections were then

incubated with primary anti-16A, 14A, or C595 (17, Abcam,

Cambridge, MA) 4°C overnight, at 1 μg/ml concentration.

The second day, after washing three times in 1X PBS

(2 min each), the slides were incubated with secondary anti-mouse

IgG-biotin antibody (1:200, Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector

laboratories, CA, USA) at room temperature for 1 h and rinsed in 1X

PBS three times (2 min each). After another 1-h incubation with the

avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (1:100, Vectastain Elite ABC Kit;

Vector Laboratories, CA, USA) and repeated washing steps with 1X

PBS, visualization was performed with the chromagen

3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA). The slides

were counterstained with hematoxylin and coverslipped with

PerMount. Sections of Jurkat-pcDNA-IRES-eGFP-MUC1 and

Jurkat-pcDNA-IRES-eGFP were used as positive and negative controls,

respectively. Isotype IgG and omission of the primary antibody were

used as negative controls for staining.

Surface plasmon resonance (SPR)

measurement of antibody affinity toward glycopeptides

Interactions of RPAPGSTAPPAHG,

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG, and RPAPGS(GalNAc)TAPPAHG with

immobilized antibody 14A and 16A were determined by surface plasmon

resonance on a Biacore T100 (GE Healthcare) instrument (18). Antibody 14A and 16A were

immobilized on a CM5 chip until reaching 5000 response units. A

reference channel was immobilized with ethanolamine, respectively.

Immobilizations were carried out at protein concentrations of 25

μg/ml in 10 mM acetate pH 5.0 by using an amine coupling kit

supplied by the manufacturer. Measurements were carried out at 25°C

in 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4 containing 150 mM NaCl and 0.005% surfactant

P20 at a flow rate of of 30 μl/min. The association time was

120 sec and dissociation time was 200 sec. The surface was

regenerated by 3 M MgCl2 solution. Data were analyzed

with BIA evaluation software (GE Healthcare).

Results and Discussion

Generation of a monoclonal antibody, 16A,

toward glycopeptide RPAPGS(GalNAc)TAPPAHG

Immunizing mice by MUC-1 transfected mutant cancer

cells induced IgG antibody responses against authentic

glyco-epitopes expressed on tumor cell surface, which could be

measured by ELISA experiments using chemically synthesized

glycopeptide RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG. We observed

individual variation of IgG titers, and selected one mouse with

titer above 5000 for hybridoma fusion. Supernatants of hybridoma

cultures were screened toward both glycopeptide

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc) TAPPAHG and non-glycosylated peptide

RPAPGSTAPPAHG.

A hybridoma clone 16A, which produces a monoclonal

antibody belonging to the IgG1 subclass, showed stronger binding to

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG (EC50=6.509±0.8019

ng/ml), but approx. 40-fold weaker binding to non-glycosylated

peptide, RPAPGSTAPPAHG (EC50=247.3±16.29 ng/ml), as measured by

ELISA experiments (Fig. 4A).

EC50 of binding to RPAPGS(GalNAc)TAPPAHG by 16A was

9.278±1.059 ng/ml, indicating at least 25-fold higher affinity as

compared to RPAPGSTAPPAHG.

| Figure 4A monoclonal antibody, 16A, binds to

glycopeptide RPAPGS(GalNAc) TAPPAHG with high affinity. (A)

Monoclonal antibody 16A was prepared as described in the text. Its

binding to glycopeptides RPAPGS(GalNAc) TAPPAHG (▪),

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG (♦) was compared to peptide

control RPAPGSTAPPAHG (▴), 2 μg/ml of biotinylated peptides

were bound to streptavidin coated ELISA plates. Monoclonal antibody

was added at indicated concentration, and binding was detected by

secondary goat anti-mouse IgG antibody, which was conjugated to

HRP. At a working concentration of 10 ng/ml, 16A antibody showed

strong binding to glycopeptide, but much weaker binding to peptide

alone. (B) A control monoclonal antibody, 14A, was generated by

screening the supernatant of hybridomas against nonglycosylated

control peptide RPAPGSTAPPAHG. 14A antibody showed same binding to

glycosylated and non-glycosylated peptides. Both 16A and 14A

antibodies showed no reactivity with 2 irrelevant glycopeptides

modified by GalNAc, PAHGVT(GalNAc)SAPD and PAHGVTS(GalNAc)APD. |

As a control, we also selected another hybridoma,

14A, by ELISA using RPAPGSTAPPAHG peptide. Not surprisingly, 14A

monoclonal antibody showed same binding specificity toward

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG and non-glycosylated RPAP

GSTAPPAHG. EC50 for RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG,

RPAPGS(GalNAc)TAPPAHG, and RPAPGSTAPPAHG were 189.3±52.55 ng/ml,

245.7±54.80 ng/ml, and 348.3±79.25 ng/ml respectively (Fig. 4).

The 16A and 14A antibodies do not bind to two other

GalNAc modified glycopeptides synthesized by our group,

PAHGVT(GalNAc)SAPD, or PAHGVTS(GalNAc)APD, as measured by ELISA

experiments, indicating that antibody binding is not only toward

the GalNAc sugar residue, but also to the specific peptide backbone

involved.

However, surface plasmon resonance measurement of

the antibody affinity to glyopeptides showed similar binding of 16A

antibody toward both glycosylated and non-glycosylated peptides

(Table II). This suggests that the

25-fold higher affinity of 16A antibody binding to glycosylated

peptides observed in ELISA experiments (Fig. 4) might be due to the conformational

changes of glycopeptides when the 2-fragment antigen-binding sites

of IgG1 molecules bind to glycopeptides in a bivalent fashion.

| Table IISPR measurement of dissociation

constants for the binding of 14A and 16A monoclonal antibodies to

glycopeptides. |

Table II

SPR measurement of dissociation

constants for the binding of 14A and 16A monoclonal antibodies to

glycopeptides.

| (Glyco)peptide | Ka (1/Ms) | Kd (1/s) | KD (nM) | Chi2

(RU2) |

|---|

| 16A | | | | |

|

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG | 5.721E+4 | 0.02794 | 488.5 | 18.6 |

|

RPAPGS(GalNAc)TAPPAHG | 3.353E+4 | 0.03120 | 930.4 | 23.1 |

| RPAPGSTAPPAHG | 7208 | 0.003898 | 540.8 | 4.95 |

| 14A | | | | |

|

RPAPGS(Ac3GalNAc)TAPPAHG | 1.600E+5 | 0.07362 | 460.2 | 10.3 |

|

RPAPGS(GalNAc)TAPPAHG | 1.172E+5 | 0.05141 | 438.6 | 19.4 |

| RPAPGSTAPPAHG | 1.218E+4 | 0.002851 | 234.0 | 3.35 |

Binding of 16A antibody to patient

samples

We further examined whether 16A antibody binds to

breast cancer tissue sections. Among 10 patients studied, we

observed strong positive staining in four patients (Table I). Fig. 5 shows a representative staining of

an estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and HER2-positive

breast tumor. In contrast, 14A antibody showed very weak binding in

immunohistochemistry experiments (data not shown).

| Table IExpression of MUC1 in breast cancer

patients as measured by 16A monoclonal antibody. |

Table I

Expression of MUC1 in breast cancer

patients as measured by 16A monoclonal antibody.

| Patient ID | Histology | ER | PR | HER2 | MUC1 (16A) |

|---|

| 1 | IDC+ILC | + | + | − | + |

| 2 | IDC | + | − | + | − |

| 3 | IDC | + | − | − | − |

| 4 | IDC | + | − | + | + |

| 5 | IDC | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | IDC | − | − | − | − |

| 7 | IDC | + | − | − | + |

| 8 | IDC | + | − | − | − |

| 9 | IDC | + | − | + | − |

| 10 | IDC | − | − | − | − |

Problems with current approaches to the

discovery of MUC1 biomarkers

In the past, most approaches focused on targeting

nonglycosylated MUC1, or MUC1 peptides with undefined glycosylation

profiles (19). While the

importance of the glycosylation pattern for the immunogenic

properties of a glycoprotein has been recognized (20), the peptide portion should not be

neglected. Recently, Schietinger and coworkers found that in a

mouse fibrosarcoma, a mutant chaperone abolished function of a

glycosyltransferase, which disrupted O-glycan core 1 synthesis, and

created a transmembrane protein as a tumor-specific antigen. This

antigen was recognized by a monoclonal antibody with exquisite

specificity. X-ray-crystallographic analysis showed that the

cognate epitope consisted of both the Tn antigen and an octapeptide

portion of the underlying protein backbone (21). Furthermore, the

glycopeptide-specific antibody showed high affinity toward cancer

antigen (Kd=10−7 M) and cured cancer in mouse models,

which is in contrast to the low affinities often observed for

antibodies toward Tn antigen (GalNAc). This result suggests that

glycopeptide epitopes may be highly immunogenic, most likely more

immunogenic than the saccharide portion alone.

Since biochemical characterization of glycan

epitopes are often challenging, we have developed a complementary

approach, that is to predict the glycolipid or glycopeptide

structures based on the central dogma of glycobiology proposed by

Kornfeld and Kornfeld (22). Since

the glycoconjugates are assembled stepwise by glycosyltransferases,

we have written computer programs that predict the glycan

structures by sequential additions of sugar units. Here we take a

novel approach to the potential discovery of new MUC1 biomarkers

via monoclonal antibodies. This approach is based on the

immunization of mice with authentic tumor cell surface MUC1. The

MUC1 epitopes expressed on the cell surface trigger B cell

responses, while the CD4 helper signals are provided by tumor

proteins (Fig. 1), when tumor

cells are lysed by xenogenicity-induced cell lysis. From these

experiments, an entire library of monoclonal antibodies can

potentially be obtained. As a first proof-of-principle experiment,

we have generated monoclonal antibodies which show higher affinity

to glycopeptide RPAPGS(GalNAc) TAPPAHG. This approach may be

complemented with conventional monoclonal antibody production via

immunization of mice with certain MUC1 glycopeptides conjugated to

adjuvants (23). Our approach

could potentially lead to a massive toolbox of monoclonal

antibodies that could be used for the discovery of authentic

biomarkers on cancer cell surfaces, and for the development of new

tools for diagnostic imaging using radioisotope-labeled monoclonal

antibodies.

Cross reactivity is an issue of all monoclonal

antibodies. In this study, we generated 16A monoclonal antibody

which preferentially binds to glycosylated peptide. The 16A

antibody showed strong binding to glycopeptide RPAPGS(GalNAc)

TAPPAHG, but much weaker binding to peptide RPAPGSTAPPAHG alone. It

has no cross reactivity with 2 other glycopeptides modified by

GalNAc, PAHGVT(GalNAc)SAPD and PAHGVTS(GalNAc)APD (Fig. 4). Identifying individual

glycopeptide epitopes will need not one, but an entire set of

monoclonal antibodies. Thus, multiple monoclonal antibodies with

preferential binding specificities will provide specific

information for an individual MUC1 glycopeptide.

In conclusion, glycopeptide epitopes expressed by

MUC1 may be predicted by bioinformatics tools. Glyco-epitopes

expressed on tumor cell surfaces may elicit antibody responses in

mice and cancer patients. Monoclonal antibodies can be generated

from mice immunized by tumor cells, and selected by ELISA

experiments using chemically synthesized glycopeptides predicted by

bioinformatics tools. Such monoclonal antibodies are valuable tools

for discovery of new biomarkers and targets for immunotherapy. This

approach was successful in generating a monoclonal antibody, 16A,

that was able to stain tissue sections. The nonglycosylated peptide

is being recognized, but 25-fold weaker than the glycopeptide.

Interestingly, 16A binds 3,4,6-tri-O-acetylated GalNAc glycopeptide

more strongly than the nonglycosylated peptide by a factor of

approximately 40, indicating that the absence of hydroxyl groups in

the sugar moiety does not abolish binding. One possible explanation

for this finding could be that the antibodies engage in

intermolecular contacts simultaneously with the peptide and those

parts of the Ac3GalNAc moiety that it has in common with

GalNAc, for example the acetamido group at position 2. Research

investigating this molecular recognition phenomenon is currently

underway.

Acknowledgements

We thank Long Vien and Laura Bover at

the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Monoclonal

Antibody Facility for technical support. This work was partially

funded by the grants from the University of Texas M.D. Anderson

Cancer Center (D.Z.), 1SC2CA148973-01 (KM), and R00CA133244

(E.A.M.). E.S.D. is supported by National Cancer Institute training

Grant T32CA009598. D.Z. is supported by NIAID grant AI079232. M.D.

Anderson Cancer Center is supported in part by NIH grant CA16672.

We thank the Biomolecule Analysis Core Facility at the Border

Biomedical Research Center/Biology/UTEP (NIH grants

2G12RR008124-16A1 and 2G12RR008124-16A1S1) for the access to the

Biacore T-100 and LC-MS instruments. D.Z. is President of

NanoCruise Pharmaceutical Suzhou Ltd., a consultant for BioTex,

Houston, TX, and an inventor involved in patents related to

technologies mentioned in this study, issued or in application.

References

|

1.

|

S GendlerJ Taylor-PapdimitriouT DuhigJ

RothbardJ BurchellA highly immunogenic region of a human

polymorphic epithelial mucin expressed by carcinoma is made up of

tandem repeatsJ Biol Chem263128201282319883417635

|

|

2.

|

JC ByrdRS BresalierMucins and mucin

binding proteins in colorectal cancerCancer Metastasis

Rev237799200410.1023/A:102581511359915000151

|

|

3.

|

SE BaldusK EngelmannFG HanischMUC1 and the

MUCs: a family of human mucins with impact in cancer biologyCrit

Rev Clin Lab Sci41189231200410.1080/1040836049045204015270554

|

|

4.

|

PK SinghMA HollingsworthCell

surface-associated mucins in signal transductionTrends Cell

Biol16467476200610.1016/j.tcb.2006.07.00616904320

|

|

5.

|

MA TarpH ClausenMucin-type O-glycosylation

and its potential use in drug and vaccine developmentBiochim

Biophys Acta1780546563200810.1016/j.bbagen.2007.09.01017988798

|

|

6.

|

RE BeatsonJ Taylor-PapadimitriouJM

BurchellMUC1

immunotherapyImmunotherapy2305327201010.2217/imt.10.17

|

|

7.

|

AM VladJC KettelNM AlajezCA CarlosOJ

FinnMUC1 immunobiology: from discovery to clinical applicationsAdv

Immunol82249293200410.1016/S0065-2776(04)82006-614975259

|

|

8.

|

E YangXF HuPX XingAdvances of MUC1 as a

target for breast cancer immunotherapyHistol

Histopathol22905922200717503348

|

|

9.

|

T JuVI OttoRD CummingsThe Tn

antigen-structural simplicity and biological complexityAngew Chem

Int Ed5017701791201110.1002/anie.20100231321259410

|

|

10.

|

R SewellM BackstromM DalzielThe

ST6GalNAc-1-sialyltransferase localizes throughout the Golgi and is

responsible for the synthesis of the tumor-associated sialyl-Tn

O-glycan in human breast cancerJ Biol

Chem28135863594200610.1074/jbc.M51182620016319059

|

|

11.

|

H CaiZH HuangL ShiZY SunYF ZhaoH KunzYM

LiVariation of the glycosylation pattern in MUC1 glycopeptide BSA

vaccines and its influence on the immune responseAngew Chem Int Ed

Engl5117191723201210.1002/anie.20110639622247051

|

|

12.

|

A Hoffmann-RöderA KaiserS WagnerSynthetic

antitumor vaccines from Tetanus toxoid conjugates of MUC1

glycopeptides with the Thomsen-Friedenreich antigen and a

fluorinesubstituted analogueAngew Chem Int Ed

Engl4984988503201020878823

|

|

13.

|

S KracunE CloH ClausenSB LeveryKJ JensenO

BlixtRandom glycopeptide bead libraries for seromic biomarker

discoveryJ Proteom Res967056714201010.1021/pr100847720886906

|

|

14.

|

A SchietingerM PhilipBA YoshidaP AzadiH

LiuSC MeredithH SchreiberA mutant chaperone converts a wild-type

protein into a tumor-specific

antigenScience314304308200610.1126/science.112920017038624

|

|

15.

|

WHO1982The World Health Organization

histological typing of breast tumors. Second editionAm J Clin

Pathol7880681619827148748

|

|

16.

|

JQ ChenJ LittonL XiaoHZ ZhangCL WarnekeY

WuX ShenS WuA SahinR KatzM BondyG HortobagyiNL BerinsteinJL MurrayL

RadvanyiQuantitative immunohistochemical analysis and prognostic

significance of TRPS-1, a new GATA transcription factor family

member, in breast cancerHorm

Cancer12133201010.1007/s12672-010-0008-8

|

|

17.

|

MR PriceJA PughF HudeczW GriffithsE

JacobsIM SymondsAJ ClarkeWC ChanRW BaldwinC595 - a monoclonal

antibody against the protein core of human urinary epithelial mucin

commonly expressed in breast carcinomasBr J

Cancer61681686199010.1038/bjc.1990.1541692469

|

|

18.

|

G SafinaApplication of surface plasmon

resonance for the detection of carbohydrates, glycoconjugates, and

measurement of the carbohydrate-specific interactions: a comparison

with conventional analytical techniques. A critical reviewAnal Chim

Acta712929201210.1016/j.aca.2011.11.016

|

|

19.

|

C BrockeH KunzSynthesis of

tumor-associated glycopeptide antigensBioorg Med

Chem1030853112200210.1016/S0968-0896(02)00135-912150854

|

|

20.

|

S DziadekH KunzSynthesis of

tumor-associated glycopeptide antigens for the development of

tumor-selective vaccinesChem

Rec3308321200410.1002/tcr.1007414991920

|

|

21.

|

CL BrooksA SchietingerSN BorisovaP KuferM

OkonT HiramaCR MackenzieLX WangH SchreiberSV EvansAntibody

recognition of a unique tumor-specific glycopeptide antigenProc

Natl Acad Sci

USA1071005610061201010.1073/pnas.091517610720479270

|

|

22.

|

R KornfeldS KornfeldAssembly of

asparagine-linked oligosaccharidesAnnu Rev

Biochem54631664198510.1146/annurev.bi.54.070185.0032153896128

|

|

23.

|

S IngaleMA WolfertT BuskasGJ

BoonsIncreasing the antigenicity of synthetic tumor-associated

carbohydrate antigens by targeting Toll-like

receptorsChembiochem10455463200910.1002/cbic.20080059619145607

|