Introduction

Tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing

ligand (TRAIL) is a member of the tumor necrosis factor cytokine

superfamily and has a homotrimeric structure. Since TRAIL induces

apoptosis in a variety of transformed and cancer cells, but not in

normal cells, it is a promising target for cancer prevention and

treatment. However, growing evidence suggests that some cancer cell

types such as malignant melanoma, glioma and non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC) cells are resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis

(1). Moreover, TRAIL-responsive

tumors acquire a resistant phenotype that renders TRAIL therapy

ineffective. Overcoming the TRAIL resistance of cancer cells is

necessary for effective TRAIL therapy and drugs potentiating TRAIL

effectiveness are urgently required (2). TRAIL binds to receptors (DRs) that

contain death domains such as death receptor (DR) 4/TRAIL-receptor

1 (TRAIL-R1) and DR5/TRAIL-R2 (3).

This binding induces oligomerization of the receptors and

conformational changes in the death domains, resulting in the

formation of a death-inducing signaling complex; and subsequent

activation of caspase-8. In turn, activated caspase-8 activates the

effector caspase-3/6/7, which executes the apoptotic process

(4,5). The activation of caspase-8 is also

linked to the intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptotic pathway.

Activated caspase-8 can cleave and activate the pro-apoptotic

Bcl-2-family molecule Bid, which in turn activates other

Bcl-2-family molecules, Bax and Bak, resulting in their

oligomerization and the formation of megachannels in the outer

mitochondrial membrane. The release of cytochrome c through

the Bax/Bak megachannels into the cytosol induces the assembly of

apoptosome and the activation of caspase-9, resulting in the

activation of caspase-3/6/7 (4).

Recently, various pro-apoptotic receptor agonists such as

recombinant human TRAIL and agonistic antibodies against DR4/DR5

have been subjected to clinical trials in a variety of cancer cell

types, including malignant melanoma and NSCLC cells. Unfortunately,

the results showed that these receptor agonists were disappointedly

only modestly effective (6).

Induction of apoptosis by the intrinsic pathway is considered to be

the major mechanism of conventional chemotherapy and is therefore a

critical target in cancer treatment. However, clinical observations

suggest that amplification of the known apoptotic pathways is not

sufficient for overcoming TRAIL resistance in cancer cells.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide

(O2−), hydrogen peroxide

(H2O2), and hydroxyl radicals (•OH) are

products of normal metabolism in virtually all aerobic organisms

and are also produced following xenobiotic exposure. Low

physiological levels of ROS function as second messengers in

intracellular signaling and are required for normal cell function,

while excessive ROS cause damage to multiple macromolecules, impair

cell function, and promote cell death (7). Imbalance between ROS production and

the ability of a biological system to detoxify oxidants or to

repair the resulting damage leads to oxidative stress. Several

lines of evidence suggest that intracellular

H2O2 is a mediator of DR ligand-induced

apoptosis in tumor cells. The flavonoid wogonin kills

TNF-α-resistant T-cell leukemia cells and sensitizes them to TNF-α-

or TRAIL-induced apoptosis by increasing intracellular

H2O2 levels (8). LY303511 sensitizes human

neuroblastoma cells to TRAIL, and intracellular

H2O2 generation plays a role in this effect

(9). On the other hand, some

evidence suggests that H2O2 acts as an

anti-apoptotic factor in DR ligand-induced apoptosis. The

continuous presence of low concentrations of

H2O2 inhibits caspase-mediated apoptosis in

Jurkat cells by inactivating pro-caspase-9 (10). It was reported that in human

astrocytoma cells, H2O2 is generated in a

caspase-dependent manner and contributes to resistance to

TRAIL-induced apoptosis (11).

Thus, the role of H2O2 in DR ligand-induced

apoptosis is controversial.

Here we demonstrate that H2O2

induces cell death in TRAIL-resistant melanoma cells via

intracellular O2− generation. Our data

suggest that the intracellular O2− mediates

ER-associated cell death in these cells. Importantly, normal

primary melanocytes were much lesser sensitive than malignant

melanoma cells to oxidative cell death.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and antibodies

Reagents were obtained from the following

manufacturers: soluble recombinant human TRAIL, Enzo Life Sciences

(San Diego, CA); DATS, Wako Pure Chemicals (Osaka, Japan);

thapsigargin, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO);

z-VAD-fluoromethylketone (fmk) (VAD), z-DEVD-fmk (DEVD), z-IETD-fmk

(IETD), z-LETD-fmk (LETD) and Mn (III) tetrakis (4-benzonic acid)

porphyrin chloride (MnTBaP), Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). z-LEVD-fmk

(LEVD) and z-ATAD-fmk (ATAD), BioVision (Mountain View, CA);

dichlorohydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), dihydroethidium

(DHE), MitoSOX™ Red (MitoSOX) and

5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethyl-benz-imidazolocarbocyamine

iodide (JC-1), Life Technologies Japan (Tokyo, Japan). Reagents

were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide and diluted with Hanks’

balanced salt solution (HBSS; pH 7.4) to a final concentration of

<0.1% before use. Dimethylsulfoxide alone at a concentration of

0.1% (vehicle) showed no effects throughout this study. Polyclonal

antibodies against X-box-binding protein-1 (XBP-1) and

glucose-related protein 78 (GRP78) were purchased from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). All the other chemicals were of

analytical grade.

Cell culture

Human A2058 and SK-MEL-2 melanoma cells were

obtained from Health Science Research Resource Bank (Osaka, Japan).

Human A375 melanoma cells were obtained from American Type Culture

Collection (Manassas, VA). These cells were cultured in high

glucose-containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM;

Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; JRH

Biosciences, Lenexa, KS) in a 5% CO2-containing

atmosphere. The cells were harvested by incubation in 0.25%

trypsin-EDTA medium (Life Technologies Japan) for 5 min at 37°C.

Normal human epidermal melanocytes were obtained from Cascade

Biologics (Portland, OR) and cultured in DermaLife Basal medium

(Kurabo, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with DermaLife M LifeFactors

(Kurabo) in a 5% CO2-containing atmosphere. The cells

were harvested by incubation in 0.25% trypsin-EDTA medium for 5 min

at 37°C.

Determination of cell death by

fluorescence microscopy

The overall cell death was evaluated by performing

fluorescence microscopy as previously described (12). Briefly, the cells (1×104

cells) were placed on 8-chamber coverslips (Asahi Glass Co., Tokyo,

Japan) and treated with the agents to be tested for 24 h at 37°C in

a 5% CO2-containing atmosphere. The cells were then

stained with 4 μM each of calcein-AM and ethidium bromide

homodimer-1 (EthD-1) to label live and dead cells, respectively,

using a commercially available kit (LIVE/DEAD®

Viability/Cytotoxicity kit; Life Technologies Japan) according to

the manufacturer’s instructions. Images were obtained using a

fluorescence microscope (IX71 inverted microscope, Olympus, Tokyo,

Japan) and analyzed using the LuminaVision software (Mitani

Corporation, Fukui, Japan).

Determination of apoptotic cell

death

Apoptotic cell death was quantitatively assessed as

previously described (12).

Briefly, the cells plated in 24-well plates (2×105

cells/well) were treated with TRAIL and the agents to be tested

alone or together for 20 h in DMEM containing 10% FBS (FBS/DMEM).

Subsequently, the cells were stained with FITC-conjugated Annexin V

and PI using a commercially available kit (Annexin V FITC Apoptosis

Detection Kit I; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The stained cells

were analyzed in a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences)

using the CellQuest software (BD Biosciences). Four cellular

subpopulations were evaluated: viable cells (Annexin

V−/PI−); early apoptotic cells (Annexin

V+/PI−); late apoptotic cells (Annexin

V+/PI+); and necrotic/damaged cells (Annexin

V−/PI+). Annexin V+ cells were

considered to be apoptotic cells.

Measurements of mitochondrial membrane

potential (ΔΨm) depolarization and caspase-3/7

activation

ΔΨm depolarization and caspase-3/7

activation were simultaneously measured by a previously described

method (12). Briefly, the cells

plated in 24-well plates (2×105 cells/well) were treated

with the agents to be tested in FBS/DMEM for 24 h, stained with the

dual sensor MitoCasp (Cell Technology Inc., Mountain View, CA), and

analyzed for their caspase-3/7 activity and ΔΨm in the

FACSCalibur using the CellQuest software. Changes in ΔΨm

were also measured using the lipophilic cation JC-1 by a previously

described method (13).

Measurement of caspase-12 activation

Activated caspase-12 in living cells was detected

using the caspase-12 inhibitor ATAD conjugated to FITC as

previously described (12). This

compound binds to active caspase-12, but not to inactive

caspase-12. The cells (2×105 cells/ml) were stained with

FITC-ATAD for 30 min at 37°C using a CaspGLOW Fluorescein

Caspase-12 Staining Kit (BioVision) according to the manufacturer’s

protocol. Fluorescence was determined using the FL-1 channel of the

FACSCalibur and analyzed using the CellQuest software.

Measurement of intracellular ROS

The production of intracellular ROS was measured

using the oxidation sensitive DHE and DCFH-DA by flow cytometry by

a previously described method (14). Briefly, cells (4×105/500

μl) resuspended in HBSS were treated with the agents to be

tested and incubated at 37°C for various time periods, then

incubated with 5 μM DHE or DCFH-DA for 15 min at 37°C. The

cells were washed, resuspended in HBSS on ice and centrifuged at

4°C. The green fluorescence (DCFH-DA) and red fluorescence (DHE)

were measured using the FL-1 and FL-2 channels of the FACSCalibur,

respectively, and analyzed using the CellQuest software.

Mitochondrial O2− generation was measured

using the mitochondria-targeting probe MitoSOX Red as previously

described (14). Briefly, the

cells (4×105/500 μl) suspended in HBSS were

treated with the agents to be tested and incubated at 37°C for

various time periods, then incubated with 5 μM MitoSOX Red

for 15 min at 37°C. The cells were washed, resuspended in HBSS on

ice, and centrifuged at 4°C. The red fluorescence was measured

using the FL-2 channels of the FACSCalibur and analyzed by

CellQuest software.

Detection of intercellular ROS by

fluorescent microscopy

The cells (1×104) were plated on

8-chamber cover glasses and treated with the agents to be tested

for 30 min at 37°C in a 5% CO2 containing atmosphere.

After removal of the medium, the cells were stained with 4

μM each of DCFH-DA and DHE to label cells producing

H2O2 and O2−,

respectively. Images were obtained with the fluorescence microscope

and analyzed using LuminaVision software.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out by the

previously described method (12).

The cells in 6-well plates (1×106 cells/ml/well) were

treated with the agents to be tested for 24 h at 37°C, washed and

lysed with SDS-sample buffer. The whole cell lysates were subjected

to SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Nippon Millipore,

Tokyo, Japan). After blocking the membranes with BlockAce

(Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Osaka, Japan) at room temperature for

60 min, GRP78 and XBP-1 proteins on the membranes were detected

using specific antibodies. Antibody-antigen complexes were detected

using the ECL Prime Western Blotting Reagent (GE Healthcare Japan,

Tokyo, Japan). To verify equal loading, the membranes were

re-probed with an antibody against β-actin or GAPDH.

Results

H2O2 induces cell

death in human TRAIL-resistant melanoma cells

First, we examined the effect of exogenously applied

H2O2 on melanoma cell survival. After

treatment with H2O2 at varying

concentrations, A375 cells were stained with calcein-AM and EthD-1

and subjected to fluorescence microscopic analysis. Live cells were

stained green with calcein-AM, while dead cells with compromised

cell membranes were stained red with EthD-1. As shown in Fig. 1A, treatment with 100 μM

H2O2 for 24 h resulted in considerable cell

death, while treatment with 100 ng/ml TRAIL had a marginal effect.

Similarly, A2058 cells and SK-MEL-2 cells were killed by

H2O2, but not by TRAIL (Fig. 1B and C). In addition, more

pronounced cell death was observed in the cells treated with TRAIL

and H2O2 than in the cells treated with

either of the agents alone. The cytotoxic effects of

H2O2 on TRAIL-resistant melanoma cells were

confirmed by apoptosis measurements using Annexin V/PI staining.

H2O2 treatment resulted in a dose- and

time-dependent increase in apoptosis in the A375 cells (Fig. 1D and E). Treatment with

H2O2 up to 30 μM for 24 h resulted in

only a modest (maximum 15%) increase in apoptosis (Annexin

V+ cells) and a moderate (35%) apoptosis was observed

after 72 h. Treatment with 100 μM H2O2

for 24 h caused a moderate apoptosis and 70–90% of the cells

underwent apoptosis at 72 h. While 30 μM

H2O2 primarily caused apoptosis with minimal

induction of necrosis, 100 μM H2O2

appeared to also cause necrosis, since not only Annexin

V+ but also Annexin V−/PI+ cells

were increased. The effect varied considerably in different

experiments depending on the basal level of Annexin

V−/PI+ cells. The level varied ranging from

1.6–9.2% and when the level was relatively high, necrotic cells

were increased up to 25%. These data suggest that under certain

circumstances, these cells spontaneously undergo necrosis and that

high concentrations of H2O2 promotes this

process. Consistent with the analysis by fluorescent microscopy,

TRAIL alone caused minimal apoptosis for 72 h. However, higher

amplitude of apoptosis was observed in the cells treated with TRAIL

plus 30 μM H2O2, but not TRAIL plus

100 μM H2O2 (Fig. 1F). H2O2

induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in all the cell lines

tested while substantial amplification of TRAIL-induced apoptosis

by H2O2 was observed in some but not all cell

lines (data not shown). The amplification was more pronounced with

H2O2 at low concentrations than with

H2O2 at high concentrations. These data show

that H2O2 treatment induces cell death in

human TRAIL-resistant melanoma cells. Subsequently, we investigated

the H2O2-induced cell death in greater detail

using A375 cells as a model cell system.

H2O2 induces

melanoma cell death in a caspase-dependent or -independent manner,

depending on the concentration applied

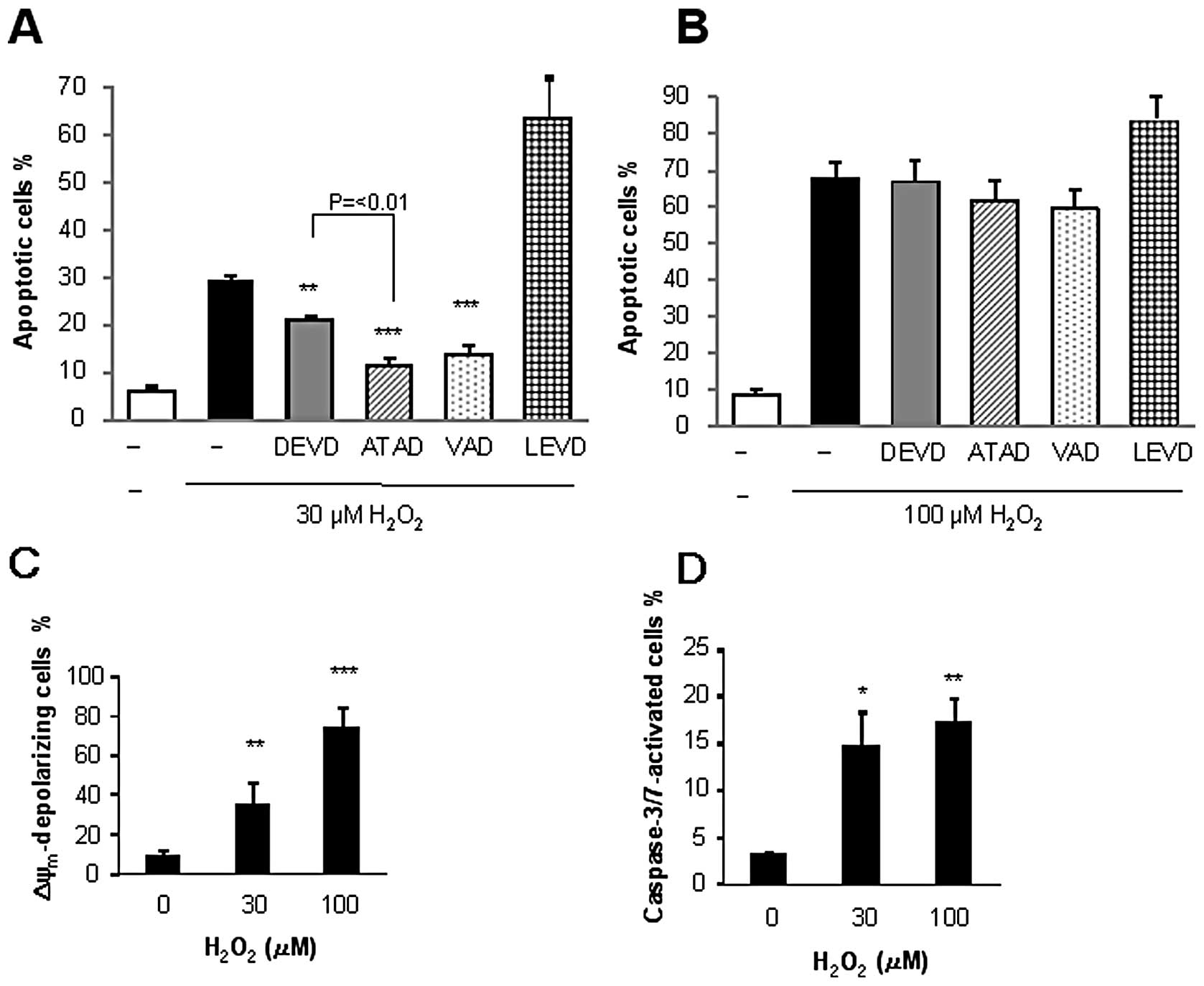

To understand the mechanisms underlying the

H2O2-induced cell death, we examined whether

or not the cell death was caspase-dependent. Analysis using

caspase-specific inhibitors revealed that

H2O2-induced apoptosis exhibited discriminate

sensitivities to the given caspase inhibitor depending on the

concentration of the oxidant applied. The general caspase inhibitor

VAD pronouncedly inhibited the apoptosis induced by 30 μM

H2O2 (maximum of 63% inhibition), while the

caspase-3/7 inhibitor DEVD reduced it by 40% (Fig. 2A). Strikingly, the caspase-12

inhibitor ATAD was as effective as VAD and was significantly more

effective than DEVD at inhibiting apoptosis. By contrast, the

caspase-4 inhibitor LEVD enhanced rather than suppressed apoptosis.

Interestingly, all these inhibitors minimally inhibited the

apoptosis induced by 100 μM H2O2

(Fig. 2B). We further examined the

effects of H2O2 on the ΔΨm and

caspase-3/7 activation, as these are hallmarks of the intrinsic

apoptotic pathway. Flow cytometric analysis using the fluorescent

ΔΨm-sensitive dye or the caspase-3/7-specific probe

revealed that H2O2 induced ΔΨm

depolarization and caspase-3/7 activation in a dose-dependent

manner (Fig. 2C and D). These data

show that H2O2 stimulates multiple death

pathways including intrinsic apoptotic and caspase-independent

apoptotic and necrotic death pathways, depending on the

concentration applied.

H2O2 induces

intracellular O2− generation, which mediates

apoptosis in human TRAIL-resistant melanoma cells

To elucidate the potential role of ROS in the

H2O2-induced cell death, we analyzed the

generation of intracellular ROS after H2O2

treatment using the oxidation-sensitive dye DCF or DHE. DCF can

react with multiple oxidants such as H2O2,

peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and •OH, but an increase in DCF

fluorescence can be considered to primarily represent increased

H2O2 level, since H2O2

is the most stable among these DCF-reacting oxidants. On the other

hand, DHE undergoes two-electron-oxidation to form DNA-binding

ethidium bromide; the reaction is mediated by

O2−, but not by H2O2 or

ONOO−. Consequently, DCFH-DA and DHE have been widely

used to assess the generation of intracellular

H2O2 and O2−,

respectively, in various rodent and human non-transformed and

transformed cells (15–18). A375 cells were treated with

H2O2 for 30 min and analyzed for their DCF or

DHE fluorescence by performing fluorescence microscopy. As shown in

Fig. 3A, only a modest increase in

DCF (green) fluorescence, but not DHE (red) fluorescence, was

observed in TRAIL-treated cells. This increase in DCF fluorescence

was transient and declined to below the basal level within 1 h. On

the other hand, unexpectedly, H2O2 treatment

increased not only DCF fluorescence but also DHE fluorescence,

indicating the production of intracellular

O2−. This oxidative response was confirmed by

flow cytometric analysis. The increase in the DHE signal was

initially observed at 1 h (Fig.

3B), and it lasted for at least 4 h; the signal was completely

abolished by superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic antioxidant MnTBaP

(Fig. 3C).

Because mitochondria are the major site of ROS

generation under physiological conditions, we examined the role of

this organelle in H2O2-induced

O2− generation. MitoSOX localizes to the

mitochondria and serves as a fluoroprobe for selective detection of

O2− in the organelle (15,19).

As shown in Fig. 3D, a substantial

increase in the MitoSOX signal was initially observed at 1 h after

treatment and the increase lasted for at least 4 h; again, MnTBaP

completely abolished the effect (Fig.

3E). Similar effects were also observed in A2058 cells (data

not shown). To understand the role of intracellular

O2− in H2O2-induced

cell death, we examined the effect of MnTBaP treatment on cell

death. The antioxidant blocked apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner

(Fig. 3F). In addition to

apoptosis, necrotic cell death induced by 100 μM

H2O2 was also reduced. On the contrary,

catalase had no effect on the cell death (data not shown). These

results show that H2O2, but not TRAIL,

induces the generation of intracellular O2−,

including inside the mitochondria in TRAIL-resistant melanoma cells

and that the O2− mediates apoptosis.

H2O2 induces ER

stress responses while scavenging of O2−

inhibits them

Caspase-12 is ubiquitously expressed and is

localized to the ER membrane. It is specifically activated by ER

stress to play a key role in the stress-induced apoptosis (22–25).

Consequently, the data obtained suggested the possible role of ER

stress including caspase-12 activation in oxidative cell death. To

test this view, we examined whether H2O2

modulates caspase-12 activation. Fluorometric analysis using

FITC-ATAD revealed that H2O2 induced

caspase-12 activation in a dose-dependent manner at concentrations

that effectively induced apoptosis (Fig. 4A and B). Furthermore, MnTBaP

treatment blocked H2O2-induced caspase-12

activation. Treatment with MnTBaP (100 μM) almost completely

abolished the effect of 30 μM H2O2 and

reduced the effect of 100 μM H2O2 by

50% (Fig. 4C). These data show

that scavenging of O2− inhibits

H2O2-induced cell death and caspase-12

activation.

To obtain further evidence for the induction of ER

stress, we assessed the levels of 2 unfolded protein response (UPR)

proteins GRP78 and XBP-1, after H2O2

treatment. Western blot analysis showed that treatment with the

positive control thapsigargin considerably upregulated the

expression of GRP78 for 24 h, while H2O2

treatment did not (Fig. 4D). On

the other hand, H2O2 increased the expression

of XBP-1, although the degree varied considerably in different

experiments. Both the active spliced form (XBP-1s) and inactive

unspliced form (XBP-1u) of XBP-1 were increased, and these effects

were totally inhibited by MnTBaP treatment (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these data show

that H2O2 induces ER stress responses and

that scavenging of O2− inhibits them.

H2O2 induces

minimal apoptosis and O2− generation in

primary melanocytes

We examined the cytotoxic effect of

H2O2 on primary normal melanocytes.

Fluorescence microscopic analysis revealed that treatment with 100

ng/ml TRAIL and 100 μM H2O2 alone or

in combination for 24 h resulted in minimal cell death (data not

shown) and apoptosis (Fig. 5A) in

normal melanocytes. In addition, only minimal intracellular and

mitochondrial O2− generation was observed

after 4-h H2O2 treatment (Fig. 5B and C). These data indicate that

melanocytes are resistant to H2O2-induced

cell death and O2− generation.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the possible

role of H2O2 in TRAIL-induced apoptosis.

TRAIL induced no or only a marginal increase in intracellular

H2O2 levels in human TRAIL-resistant melanoma

cells. On the other hand, exogenously applied

H2O2 at relatively low concentrations (30–100

μM) substantially killed these cells. In addition, under

certain circumstances, a synergistic induction of apoptosis was

observed when H2O2 and TRAIL were applied in

combination. Collectively, these data indicate that

H2O2 is a modulator rather than primary

mediator of the cytotoxic effect of TRAIL. Interestingly, the

synergism was more clearly observed with low concentrations of

H2O2 than with high concentrations of

H2O2, suggesting that as the concentration

increases, in addition to its intrinsic mechanism,

H2O2 also stimulates apoptotic pathways that

are at least partially shared with TRAIL.

H2O2 induced apoptotic or necrotic cell

death, depending on the concentration of the oxidant applied. The

intrinsic mitochondrial pathway is considered to be the major

mechanism of apoptosis. Consistent with this view, the cell death

induced by low concentrations of H2O2 was

caspase-dependent and was associated with increased ΔΨm

collapse and caspase-3/7 activation. However, inhibition of

caspase-3/7 only partially blocked apoptosis. These data suggest

that while the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway does play a role in

inducing apoptosis, another caspase cascade may also be involved in

this caspase-dependent apoptosis.

ER can initiate cell death through a pathway that

is independent of intrinsic (mitochondria) and extrinsic (death

receptor) pathways. ER-associated cell death is thought to be

mediated by caspase-12 (22–26).

A variety of cellular conditions such as glucose deprivation,

hypoxia, disturbance of calcium homeostasis and excess ROS can

cause ER stress, which is characterized by the accumulation of

unfolded proteins. ER stress activates the adaptive UPR, which

protects cells owing to protein synthesis inhibition, chaperone

protein upregulation and an increase in protein degradation. If UPR

activation is not able to relieve ER stress, the cells undergo

ER-mediated apoptosis (22–26).

Upon ER stress, the chaperone molecule GRP78 dissociates from the

transmembrane proteins, such as inositol requiring enzyme 1α

(IRE1α) and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6). The free ATF6

translocates to the Golgi apparatus where it is activated. The

active ATF6 in turn enters the nucleus and initiates the expression

of the transcription factor XBP-1. Activated IRE1α splices the

transcribed XBP-1 mRNA to allow translation of the mature XBP-1

protein, which acts as a transcription factor and mediates the

transcriptional upregulation of numerous genes involved in ER

function (20,21,23).

Our data showed that H2O2 induced ER stress,

as shown by caspase-12 activation and upregulated the expression of

the mature XBP-1 protein. Furthermore, inhibition of caspase-12

strongly blocked the H2O2-induced apoptosis.

Collectively, our data suggest that the ER-mediated apoptotic

pathway involving caspase-12 plays a key role in

H2O2-induced apoptosis.

Interestingly, while activation of caspase-12

following the induction of ER stress during apoptosis has been

reported in various mammalian cells including mouse, rat, rabbit

and cow (26), the role of

caspase-12 in ER-mediated apoptosis of human cells is a matter of

debate. This might be because the human caspase-12 gene contains

several mutations that block its expression (27). Nevertheless, an increasing body of

evidence suggests that a caspase-12-like protein exists and is

activated in human cells following the induction of ER stress by

divergent causes, including H2O2, cisplatin,

tetrocarcin A and hyperthermia (12,28–33).

Recently, adaptation to ER stress was suggested to

be a key driver of malignancy and resistance to therapy in cancer

cells, including malignant melanoma cells, with GRP78 playing a key

role in this adaptation (34,35).

GRP78 expression is associated with tumor development and growth

and is correlated with resistance to chemotherapeutic drugs such as

cisplatin and adriamycin (34–36).

In this study, thapsigargin substantially increased GRP78

expression, while H2O2 decreased GRP78

expression in melanoma cells; these cells were killed by

H2O2, but not thapsigargin. On the other

hand, GRP78 expression was minimally increased in

thapsigargin-sensitive Jurkat leukemia cells (Inoue and Suzuki,

unpublished data). GRP78 has been shown to exert its anti-apoptotic

function by inhibiting caspase-4 or caspase-7 activity (36). However, caspase-4 appears to

regulate H2O2-induced apoptosis negatively

rather than positively, as inhibition of the enzymatic activity

significantly enhanced the apoptosis. Given the structural

similarity between caspase-4 and caspase-12, it is possible that

GRP78 may also target caspase-12 to counteract ER-mediated

apoptosis.

ROS levels are controlled by the antioxidant

defense system, including the antioxidant enzymes manganese- or

copper-zinc-containing superoxide dismutase, which catalyze the

dismutation of O2− into

H2O2, and catalase and glutathione

peroxidase, which degrade H2O2. Our data

showed that these enzymes had no effects on

H2O2-induced cell death.

H2O2 is a diffusible molecule that is readily

transported across the cell membrane to the extracellular space.

Consequently, scavenging of extracellular

H2O2 by catalase may eventually result in a

decrease in the intracellular H2O2 level.

Therefore, the ineffectiveness of catalase to suppress

H2O2-induced cell death suggests that

H2O2in situ plays a minor role in the

cell death. The ineffectiveness of MnTBaP to enhance

H2O2-induced cell death supports this view,

since MnTBaP increased intracellular H2O2

levels. Instead, our data showed that O2− is

a key mediator in H2O2-induced cell death.

H2O2 induced persistent intracellular

O2− generation at concentrations that

effectively induced cell death. Consistent with the role of

mitochondria as the most common source of ROS during apoptosis,

H2O2 induced substantial mitochondrial

O2•− generation. Moreover, MnTBaP, a cell

permeable SOD mimetic, reduced the

H2O2-induced mitochondrial

O2− generation and cell death, In addition,

MnTBaP blocked H2O2-induced ER stress

responses such as caspase-12 and XBP-1 activation. Collectively,

these data suggest O2− most likely derived

from the mitochondria mediates ER-mediated apoptosis, thereby

promoting H2O2-induced cell death.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated for the first

time that H2O2 induces cell death in

TRAIL-resistant human melanoma cells via intracellular

O2− generation. Further studies on the

mechanisms by which H2O2 induces this

O2− generation are under way. Since melanoma

cells are much more susceptible to oxidative cell death than normal

primary melanocytes, H2O2 has therapeutic

potential in the treatment of malignant melanoma.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr M. Murai for her

technical assistance. This study was supported in part by a

Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports,

Science and Technology (KAKENHI 23591631; to Y.S.) and

Grants-in-Aid from Nihon University (to Y.S.).

References

|

1

|

Dyer MJ, MacFarlane M and Cohen GM:

Barriers to effective TRAIL-targeted therapy of malignancy. J Clin

Oncol. 25:4505–4506. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Johnstone RW, Frew AJ and Smyth MJ: The

TRAIL apoptotic pathway in cancer onset, progression and therapy.

Nat Rev Cancer. 8:782–798. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

LeBlanc HN and Ashkenazi A: Apo2L/TRAIL

and its death and decoy receptors. Cell Death Differ. 10:66–75.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wang S: The promise of cancer therapeutics

targeting the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand and TRAIL

receptor pathway. Oncogene. 27:6207–6215. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Sayers TJ: Targeting the extrinsic

apoptosis signaling pathway for cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol

Immunother. 60:1173–1180. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Dimberg LY, Anderson CK, Camidge R,

Behbakht K, Thorburn A and Ford HL: On the TRAIL to successful

cancer therapy? Predicting and counteracting resistance against

TRAIL-based therapeutics. Oncogene. May 14–2012.(Epub ahead of

print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Circu ML and Aw TY: Reactive oxygen

species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol

Med. 48:749–762. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fas SC, Baumann S, Zhu JY, et al: Wogonin

sensitizes resistant malignant cells to TNFalpha- and TRAIL-induced

apoptosis. Blood. 108:3700–3706. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shenoy K, Wu Y and Pervaiz S: LY303511

enhances TRAIL sensitivity of SHEP-1 neuroblastoma cells via

hydrogen peroxide-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase

activation and up-regulation of death receptors. Cancer Res.

69:1941–1950. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Barbouti A, Amorgianiotis C, Kolettas E,

Kanavaros P and Galaris D: Hydrogen peroxide inhibits

caspase-dependent apoptosis by inactivating procaspase-9 in an

iron-dependent manner. Free Radic Biol Med. 43:1377–1387. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Choi K, Ryu SW, Song S, Choi H, Kang SW

and Choi C: Caspase-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species

in human astrocytoma cells contributes to resistance to

TRAIL-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 17:833–845. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Suzuki Y, Inoue T, Murai M, et al:

Depolarization potentiates TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human

melanoma cells: role for ATP-sensitive K+ channels and

endoplasmic reticulum stress. Int J Oncol. 41:465–475.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Suzuki Y, Yoshimaru T, Inoue T and Ra C:

Mitochondrial Ca2+ flux is a critical determinant of the

Ca2+ dependence of mast cell degranulation. J Leukoc

Biol. 79:508–518. 2006.

|

|

14

|

Inoue T, Suzuki Y, Yoshimaru T and Ra C:

Reactive oxygen species produced up-or downstreame of calcium

influx regulate proinflammatory mediator release from mast cells:

role of NADPH oxidase and mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Acta.

1783:789–802. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Robinson KM, Janes MS, Pehar M, et al:

Selective fluorescencet imaging of superoxide in vivo using

ethidium-based probes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 103:15038–15043.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Carter WO, Narayanan PK and Robinson JP:

Intracellular hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion detection in

endothelial cells. J Leukoc Biol. 55:253–258. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Devadas S, Hinshaw JA, Zaritskaya L and

Williams MS: Fas-stimulated generation of reactive oxygen species

or exogenous oxidative stress sensitize cells to Fas-mediated

apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 35:648–661. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Suzuki Y, Yoshimaru T, Inoue T and Ra C:

Discrete generations of intracellular hydrogen peroxide and

superoxide in antigen-stimulated mast cells: reciprocal regulation

of store-operated Ca2+ channel activity. Mol Immunol.

46:2200–2209. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Mukhopadhyay P, Rajesh M, Kashiwaya Y,

Haskó G and Pacher P: Simple quantitative detection of

mitochondrial superoxide production in live cells. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 358:203–208. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Breckenridge DG, Germain M, Mathai JP, et

al: Regulation of apoptosis by endoplasmic reticulum pathways.

Oncogene. 22:8608–8618. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Boyce M and Yuan J: Cellular response to

endoplasmic reticulum stress: a matter of life or death. Cell Death

Differ. 13:363–373. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Nakagawa T, Zhu H, Morishima N, et al:

Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and

cytotoxicity by amyloid-beta. Nature. 403:98–103. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Groenendyk J and Michalak M: Endoplasmic

reticulum quality control and apoptosis. Acta Biochim Pol.

52:381–395. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rao RV, Castro-Obregon S, Frankowski H, et

al: Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death

program. An Apaf-1-independent intrinsic pathway. J Biol Chem.

277:21836–21842. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Morishima N, Nakanishi K, Takenouchi H,

Shibata T and Yasuhiko Y: An endoplasmic reticulum stress-specific

caspase cascade in apoptosis. Cytochrome c-independent activation

of caspase-9 by caspase-12. J Biol Chem. 277:34287–34294. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Szegezdi E, Fitzgerald U and Samali A:

Caspase-12 and ER-stress-mediated apoptosis: the story so far. Ann

NY Acad Sci. 1010:186–194. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Fischer H, Koenig U, Eckhart L and

Tschachler E: Human caspase 12 has acquired deleterious mutations.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 293:722–726. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pallepati P and Averill-Bates DA:

Activation of ER stress and apoptosis by hydrogen peroxide in HeLa

cells: protective role of mild heat preconditioning at 40°C.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 12:1987–1999. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mandic A, Hansson J, Linder S and Shoshan

MC: Cisplatin induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and

nucleus-independent apoptotic signaling. J Biol Chem.

278:9100–9106. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tinhofer I, Anether G, Senfter M, et al:

Stressful death of T-ALL tumor cells after treatment with the

anti-tumor agent Tetrocarcin-A. FASEB J. 16:1295–1297.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Xie Q, Khaoustov VI, Chung CC, et al:

Effect of tauroursodeoxycholic acid on endoplasmic reticulum

stress-induced caspase-12 activation. Hepatology. 36:592–601. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Trisciuoglio D, Uranchimeg B, Cardellina

JH, et al: Induction of apoptosis in human cancer cells by

candidaspongiolide, a novel sponge polyketide. J Natl Cancer Inst.

100:1233–1246. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Shellman Y, Howe WR, Miller LA, et al:

Hyperthermia induces endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptosis in

melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer cells. J Invest Dermatol.

128:949–956. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hersey P and Zhang XD: Adaptation to ER

stress as a driver of malignancy and resistance to therapy in human

melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 21:358–367. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rutkowski DT and Kaufman RJ: That which

does not kill me makes me stronger: adapting to chronic ER stress.

Trends Biochem Sci. 32:469–476. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Jiang CC, Mao ZG, Avery-Kiejda KA, Wade M,

Hersey P and Zhang XD: Glucose-regulated protein 78 antagonizes

cisplatin and adriamycin in human melanoma cells. Carcinogenesis.

30:197–204. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|