Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a common

malignancy, the third cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide

(1). Frequent intrahepatic and

extrahepatic metastases are the main factors contributing to the

high mortality of HCC patients (2). Previously, bone metastases were

considered less common in patients with HCC. However, due to the

improved duration of intrahepatic primary tumors, bone metastases

from HCC seem to be increasing and frequently recorded (3,4).

Thus, early diagnosis of bone metastasis plays a pivotal role in

the therapeutic regimen and the assessing prognosis (5). It is generally considered that cancer

is a dynamic exchange between tumor cells and surrounding host

cells, as first proposed in 1889 by Stephen Paget who indicated

that the seeding of metastatic cancer cells depended on the host

organ microenvironment (the ‘seed and soil’ concept) (6). To our knowledge, soluble factors

secreted by host cells and direct cell-to-cell interactions are

deemed to contribute to the preferential metastasis and growth of

cancer cells in bone (7,8), however, the underlying mechanism of

metastasis of HCC in the bone is poorly understood.

Marrow/mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) play a major

role of tumor stroma in bone microenvironment and have an effect on

growth and metastasis of human malignancies. However, the exact

effect of MSCs on tumor growth and progress is still under debate

(9). The contradiction exists in

some cancer cells, including melanoma (10,11),

breast cancer (12), colon cancer

(13), Kaposi’s sarcoma (14), and prostate cancer (15). In HCC, some studies demonstrated

that MSCs contributed to tumor progression (16–18),

several other studies demonstrated that MSCs could inhibit

metastasis (19–21) and tumorigenesis (22). MSCs in HCC metastasis remains

controversial. MSCs secrete various cytokines that have both

paracrine and autocrine functions, besides MSCs are able to

generate a direct effect through intercellular signaling via

physical contact with tumor cells (23).

CCL5 (also known as regulated upon activation,

normally T cell expressed and secreted, or RANTES) belongs to the

CC family of inflammatory chemokines and is expressed by many liver

and infiltrating cells (24), and

interacts with the G-protein coupled receptors CCR1, CCR3 and CCR5.

CCL5 is also secreted from tumor or stromal cells, and may act in

an autocrine or a paracrine manner on cancer cells to enhance their

migration and invasion (12,25,26).

It was shown that CCL5 exhibited in vitro migratory and

invasive stimulus on HCC cells (27,28),

but some other studies reported that increased CCL5 expression

might be connected with favorable outcomes in some cancer diseases

(29,30). However, the effects of CCL5

mediated by HS-5 cells and detailed mechanisms of Huh7 cell

progress are largely unknown, thus, there is an urgent need for

increased understanding.

Based on the studies above, we aimed to investigate

the effects of CCL5 from HS-5 cells on Huh7 cells, as well as the

underlying mechanisms. Our investigation found that HS-5-CM could

promote the proliferation, migration and invasion of Huh7 cells,

and inhibited apoptosis. CCL5 down-regulation inhibited the effects

of HS-5 cells on Huh7 cells migration and invasion via PI3K-Akt

signaling pathway and reduced MMP-2 expression. These results

suggest that MSCs mediated CCL5 promoting migration and invasion of

Huh7 cells and it may offer a novel strategy to efficiently inhibit

metastasis.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and reagents

The human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines Huh7,

SMMC-7721, HepG2 and normal human liver cell lines LO2 were kindly

provided by Dr Tongchuan He (University of Chicago Medical Center),

and bone marrow stromal cell lines HS-5 were purchased from

American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cells were

maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, HyClone,

USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA) and

100 U/ml streptomycin/penicillin at 37°C in 5% CO2. The

primary antibodies used in this study were: rabbit anti-Akt

monoclonal antibody, rabbit anti-phosphor-Akt monoclonal antibody,

rabbit anti-ERK1/2 monoclonal antibody and rabbit

anti-phosphor-ERK1/2 monoclonal antibody and were obtained from

Cell Signaling Technology. Rabbit anti-MMP-2 polyclonal antibody

was purchased from Immunoway (Immunoway, USA). Mouse anti-β-actin

monoclonal antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biothechnology.

Secondary antibodies included HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG

antibody and anti-rabbit IgG antibody were purchased from Zhongshan

Goldenbridge Biotechnology. Specific inhibitors of PI3K (LY294002)

and ERK1/2 (PD98059) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology.

CCL5 neutralization antibody was purchased from Peprotech.

Collection of HS-5 cell conditioned

medium (HS-5-CM)

HS-5 cells were plated in a 100 mm2

culture dish at a density of 80%, for 6 h, for cells adherence,

culture medium was changed to serum-free DMEM (SF DMEM). The

culture supernatant was harvested every day for 3 days and then all

medium were pooled, and sterile filtered. The HS-5-CM was stored at

−20°C.

Co-culture experiment

The co-culture experiment was set up in duplicates

using 6-well Transwell inserts (Millipore, USA) with 0.4 μm

pore size. In Transwell chamber, HS-5 cells were plated at the

density of 105 cells/well in 1 ml, whereas Huh7 or

SMMC-7721 or LO2 cells were plated in the 6-well plates at the

density of 2×105 cells/well in 2 ml. Cells were left to

adhere for 6 h before being put together in the SF DMEM for 3 days,

and cells alone were used as control.

Cell viability assay

MTT [3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,

5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay was used to detect cell

viability. A total of 2×103 cells/well were cultured in

96-well plates and treated with fresh DMEM, 50% HS-5-CM

(CM:DMEM=1:1) or 100% HS-5-CM containing 1% FBS for 24, 48 and 72

h. After the indicated hours of culture, the MTT reagent (Sigma,

St. Louis, MO, USA) was added (20 μl/well), and incubated

for 4 h at 37°C. Dimethyl sulfoxide was added to dissolve the

formazan product for 10 min at room temperature. Finally, the

absorbance was measured daily for the next three days at 492 nm

using a microplate reader. Each group was done in sextuplicate, and

the overall experiment was repeated three times.

Flow cytometry

Cell cycle and cell apoptosis analysis were assessed

by flow cytometry. Cells were divided into 3 groups: i) control

group, Huh7 cells; ii) co-culture group, Huh7 cells were

co-cultured with HS-5 cells; and iii) HS-5-CM group, Huh7 cells

were treated with HS-5-CM. In brief, cells were seeded into 6-well

plates at a density of 2×105 cells/well. Every

experiment was repeated twice in each group. Cells were harvested,

re-suspended in 1 ml cold PBS. Samples were fixed with pre-cold 75%

enthanol for 1 h at 4°C by cell cycle assay, and other samples were

added using propidium iodide (PI) and FITC-Annexin V for cell

apoptosis analysis according to the manufacturer’s protocol

(Invitrogen, USA). Respectively, data were analyzed using FACsorter

(Becton Dickinson, CA, USA).

Wound-healing assay, Transwell chamber

migration and invasion assay

For wound-healing assay, cells were grown to 95%

confluence and the monolayer was scratched with a pipette tip, and

then culture medium was replaced with fresh DMEM or 50% HS-5-CM or

100% HS-5-CM containing 1% FBS. Cells that migrated into the

scratched area were compared using bright field microscopy at 48 h.

Cell migration and invasion assay were performed by 24-well

Transwell chambers (8 μm pore size, Millipore) without or

with ECM gel (Sigma). Briefly, cells (5×104/400

μl) in SF DMEM were seeded onto the upper chambers, and

fresh DMEM or 50% HS-5-CM or 100% HS-5-CM (600 μl/well)

containing 20% FBS added to the lower chambers. After 24 h, cells

that migrated to the underside of the filter were fixed with

methanol and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and

counted by brightfield microscopy. All the experiments were

repeated three times.

Animal studies

The in vivo experiments were performed in

accordance with the guidelines established by the Animal Care and

Use Committee, of Chongqing University Laboratory Animal Research.

The 4-6-week old male NOD/SCID mice were randomly divided into 2

groups (n=4/group), respectively, and were injected subcutaneously

with a mixture of equal number of HS-5 cells (3×106) and

Huh7 cells (3×106) or with Huh7 cells (6×106)

alone. Tumor volume was measured every 10 days with vernier

calipers, and calculated in mm3 as ab2/2,

where a and b represent the largest and smallest tumor diameters,

respectively. The mice were sacrificed after 70 days, and tumor

tissues, livers and lungs were collected and stained using H&E

in order to examine the histopathology.

Total RNA isolation, RT-PCR, and

real-time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

Huh7 cells were co-cultured with HS-5 cells or alone

in SF DMEM for 3 days, total RNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagents

(Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total

RNA (2 μg) was used to generate cDNA templates for reverse

transcriptase-PCR. Touchdown PCR analysis determined the gene

expression levels and was performed by using the following program:

95°C × 2 min for one cycle, 10 cycles at 92°C × 20 sec, 65°C × 30

sec, and 70°C × 40 sec with a decrease of one degree per cycle, and

25 cycles at 92°C × 20 sec, 55°C × 30 sec, and 70°C × 40 sec. 70°C

× 5 min for one cycle. Real-time PCR was run in the Rotor-Gene 6000

Real-Time PCR machine (Corbett Research, Australia) using SYBR

Premix Ex Taq (Takara) with the following protocol: initial

activation of HotStar Taq DNA polymerase at 95°C for 10 min, then

45 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 20 sec. GAPDH was used as

an internal control. The primer efficiency was confirmed to be high

(>90%) and comparable (Table

I). Data were analyzed according to the 2−ΔΔCt

method. The expression levels of mRNA were normalized to GAPDH.

| Table I.The sequence of PCR primers for each

gene. |

Table I.

The sequence of PCR primers for each

gene.

| Genes | Forward primers

(5′→3′) | Reverse primers

(5′→3′) |

|---|

| CXCL12 |

TGAGCTACAGATGCCCATGC |

TTCTCCAGGTACTCCTGAATCC |

| CXCR4 |

ACGCCACCAACAGTCAGA |

ACAACCACCCACAAGTCA |

| CXCR7 |

TTATCGCTGTCTTCTACTTCC |

CTTGGTGAGCCCTGTTTT |

| CX3CL1 |

AAGGAGCAATGGGTCAAGG |

ACGGGAGGCACTCGGAAA |

| CX3CR1 |

CACCGACATTTACCTCCT |

TTGGCTTTCTTGTGGTTCTT |

| CXCL8 |

ACTCCAAACCTTTCCACC |

CTTCTCCACAACCCTCTG |

| CXCR1 |

AAAATGGCGGATGGTGTT |

GACGAAGAAGTGTAGGAGGT |

| CCL5 |

TTGCTACTGCCCTCTGCG |

CACTTGGCGGTTCTTTCG |

| CCR1 |

CCCTTGGAACCAGAGAGAAG |

CAAACTCTGTGGTCGTGTCA |

| CCR3 |

TCGTTCTCCCTCTGCTCG |

AGATGCTTGCTCCGCTCA |

| CCR5 |

CTGCTACTCGGGAATCCTAAA |

CATAGCTTGGTCCAACCTGTTA |

| MMP-2 |

CTACGATGATGACCGCAAGT |

CAGTCCGCCAAATGAACC |

| MMP-7 |

GGAGGAGATGCTCACTTCGAT |

AGGAATGTCCCATACCCAAAGA |

| MMP-9 |

GGGACGCAGACATCGTCATC |

TCGTCATCGTCGAAATGGGC |

| GAPDH |

CAGCGACACCCACTCCTC |

TGAGGTCCACCACCCTGT |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA)

To determine quantification of the levels of CCL5

secreted in the supernatants from co-culture or non co-culture, the

culture medium was collected and detected by using ELISA Kits

(RayBiotech, ELH-RANTES-001), according to the manufacturer’s

protocol. Briefly, samples were added to the coated wells with CCL5

mAb of 96-well plates and incubated for 2.5 h at room temperature,

washed four times and then incubated with an HRP-linked

streptavidin solution for 30 min at room temperature in the dark.

The absorbance was then measured at 450 nm on the microplate reader

(Sunrise Remote, Switzerland) immediately. All the experiments were

repeated for three times.

Gelatin zymography of MMP-2 and MMP-9

activity

Equal amount of protein from Huh7 cells co-cultured

with HS-5 cells or alone were mixed with SDS buffer, and were added

onto a 5% (w/v) stacking polyacrylamide gel and separated on a 10%

(w/v) polyacrylamide gel containing 1.0 mg/ml porcine gelatin

(Sigma) for the detection of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity. After

electrophoresis, gels were washed twice for 40 min in 2.5% Triton

X-100 (Sigma) to remove SDS, and incubated for 42 h at 37°C in 50

mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6) containing 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM CaCl2

and 0.02% Brij-35, and gels were stained for 3 h in 45%

methanol/10% acetic acid containing 0.5% Coomassie brilliant Blue

R-250 (w/v). Finally, destained with a solution containing 5%

acetic acid until clear bands of gelatinolysis appeared on a dark

background, proteolytic activity was detected as clear bands on a

blue backgroup of the Coomassie Blue staining gel.

Western blot analysis

Western blot was done using standard protocols. In

brief, Huh7 cells co-cultured or non co-cultured were washed three

times with cold PBS and lysed in RIPA lysis buffer, and cell lysate

was denatured after boiling. The protein concentration was measured

according to NanoDrop100 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo

Scientific, USA). Equal amount of proteins were loaded onto 10%

SDS-PAGE gels, and transferred subsequently onto PVDF membranes.

After blocking with 5% BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin, Solarbio) in

TBST, the membranes were probed with the primary antibody, and

followed by incubation with a secondary antibody conjugating with

horseradish peroxidase. Protein levels were quantified with

SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate kit.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation

(SD). Comparisons were made using independent sample Student’s

t-test in GraphPad prism 5. Statistical significance is indicated

as p<0.05.

Results

HS-5 cells stimulate proliferation and

suppress apoptosis of Huh7 cells in vitro

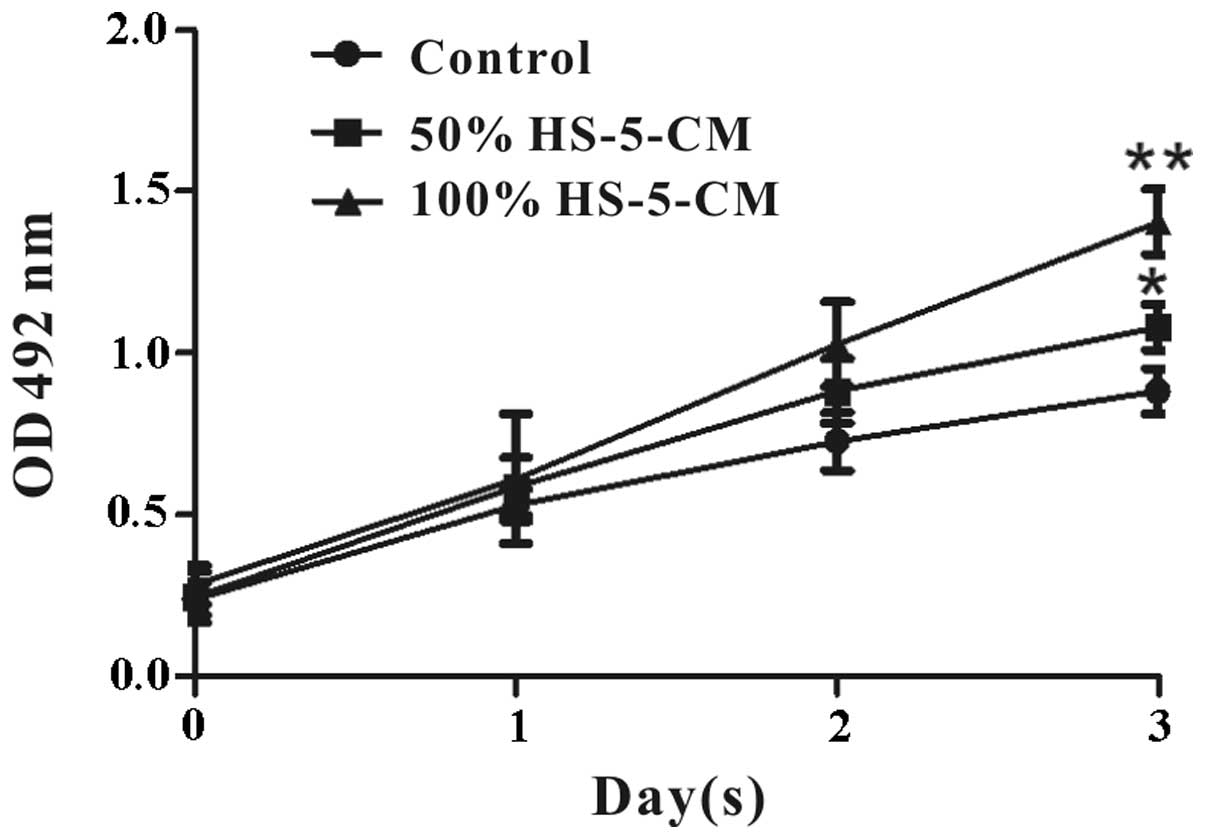

The effects of HS-5 cells on Huh7 cell viability

in vitro were evaluated by MTT assay. It revealed that Huh7

cell viability treated with HS-5-CM increased obviously and

time-dependently compared with control (Fig. 1). To further investigate the

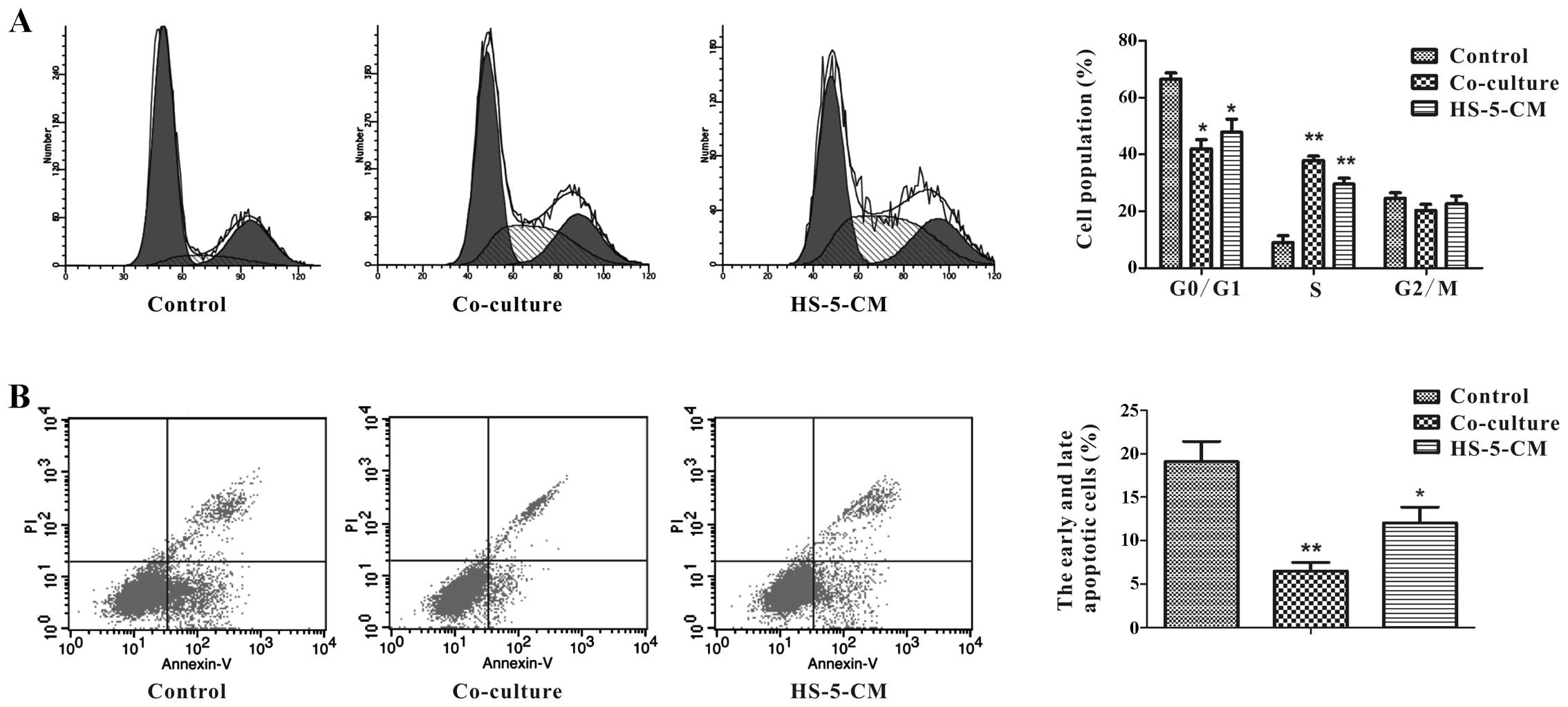

mechanisms of HS-5 cell-induced proliferation of Huh7 cells, flow

cytometry was performed to measure the cell cycle. In order to

study how HS-5 cells affect Huh7 cell growth in tumor

microenvironment, we adopted two ways to culture Huh7 cells:

co-cultured with HS-5 cells, and treatment with HS-5-CM, subsequent

experiments were done using 100% HS-5-CM. Respectively, Huh7 cells

in co-culture group (37.85±1.52%) and in HS-5-CM group

(29.56±2.03%) were at S phase of cell cycle at day 3, which was

significantly higher than the control (8.96±2.34%) (Fig. 2A). These two ways had different

degrees of increase in S phase, but the data demonstrated that HS-5

cells could promote Huh7 cell proliferation.

The proportion of Huh7 cells undergoing apoptosis

was determined by flow cytometry analysis. After 3 days, the data

showed the apoptosis ratio (early + late) of Huh7 cells in

co-culture group was approximately 6.50%, and it was significantly

decreased compared to the control group, although HS-5-CM was not

distinct in decreasing the apoptotic percentage of Huh7 cells, the

small change implied that HS-5 cells could suppress Huh7 cell

apoptosis (Fig. 2B).

HS-5 cells significantly promote

migration and invasion of Huh7 cells in vitro

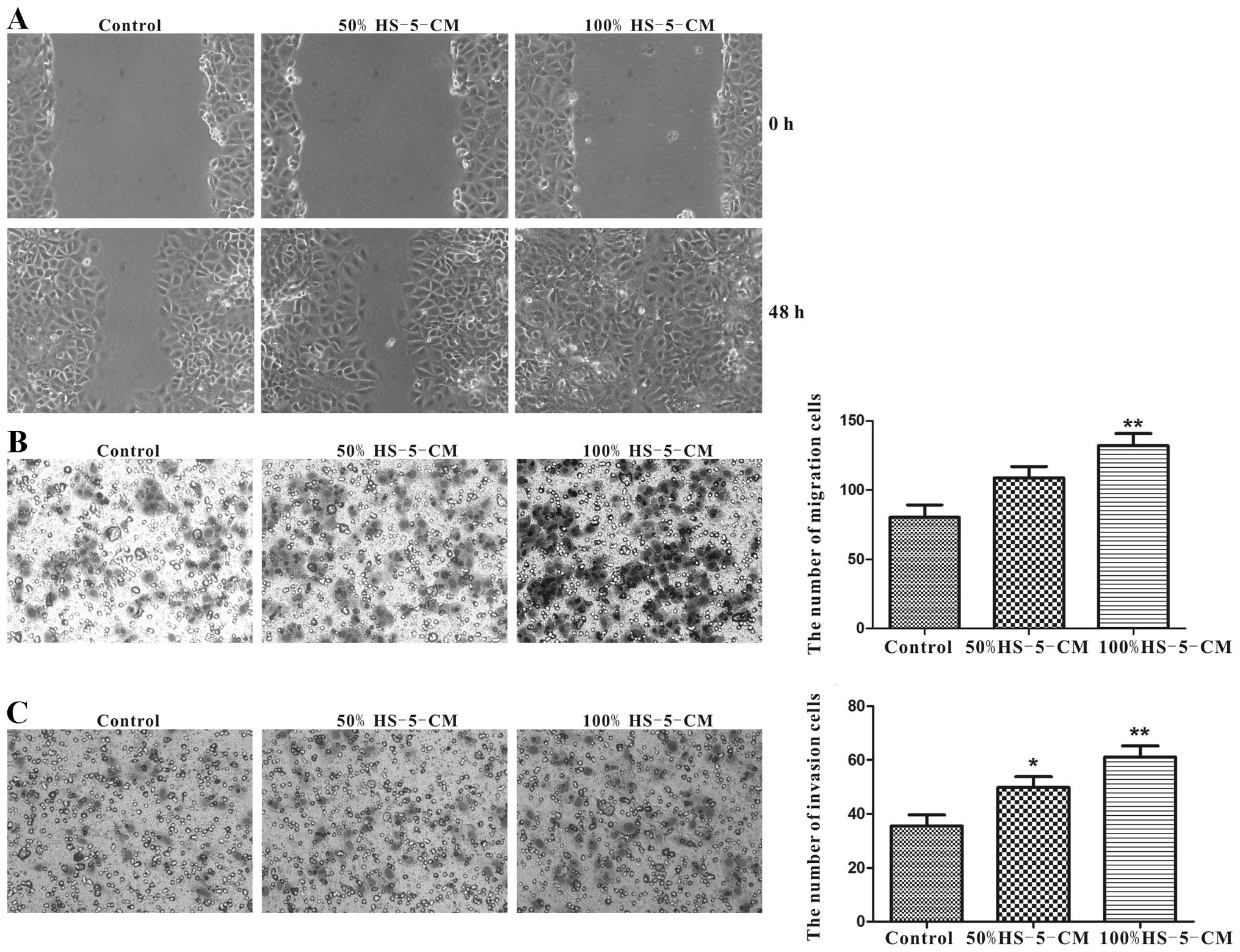

As cell migration and invasion abilities are

important determinants in the progression of HCC metastasis, the

potential to migrate was tested in the commonly used wound-healing

assay. After cultured with HS-5-CM for 48 h, the motility of Huh7

cells was significantly accelerated compared with control,

especially in 100% HS-5-CM (Fig.

3A). Transwell assay was carried out to verify the migration

potency. In line with the wound-healing experiment, it demonstrated

that 100% HS-5-CM prominently increased the migration potency of

Huh7 cells compared to the control (Fig. 3B). Applying Transwell assay to test

the invasion property of Huh7 cells for 24 h, respectively, the

number of transmembrane cells in 50% HS-5-CM group and 100% HS-5-CM

group was remarkably increased compared to the control group

(Fig. 3C).

HS-5 cells promote tumor growth of Huh7

cells in vivo

A critical experiment for determining whether HS-5

cells affect tumor growth of HCC is the in vivo

tumorigenicity assay. Therefore, we sought to validate our in

vitro findings by using an in vivo model. It found that

HS-5 cells accelerated the growth of Huh7 tumors, up to 20 days,

there was no significant difference in the two groups, while the

tumor volumes became palpable after 20 days, the Huh7 group grew

from 150 to 2,522.4 mm3 and the co-culture group grew

from 200 to 3,321.8 mm3 (Fig. 4A and B). These results were

consistent with the in vitro observation that HS-5 cells

markedly promoted Huh7 cells growth. H&E staining showed no

variance in heterogeneity between the two groups (Fig. 4C). Tumor cells were not found in

the liver and lung tissues between the two groups (data not

shown).

Co-culture with Huh7 cells increases CCL5

expression in HS-5 cells

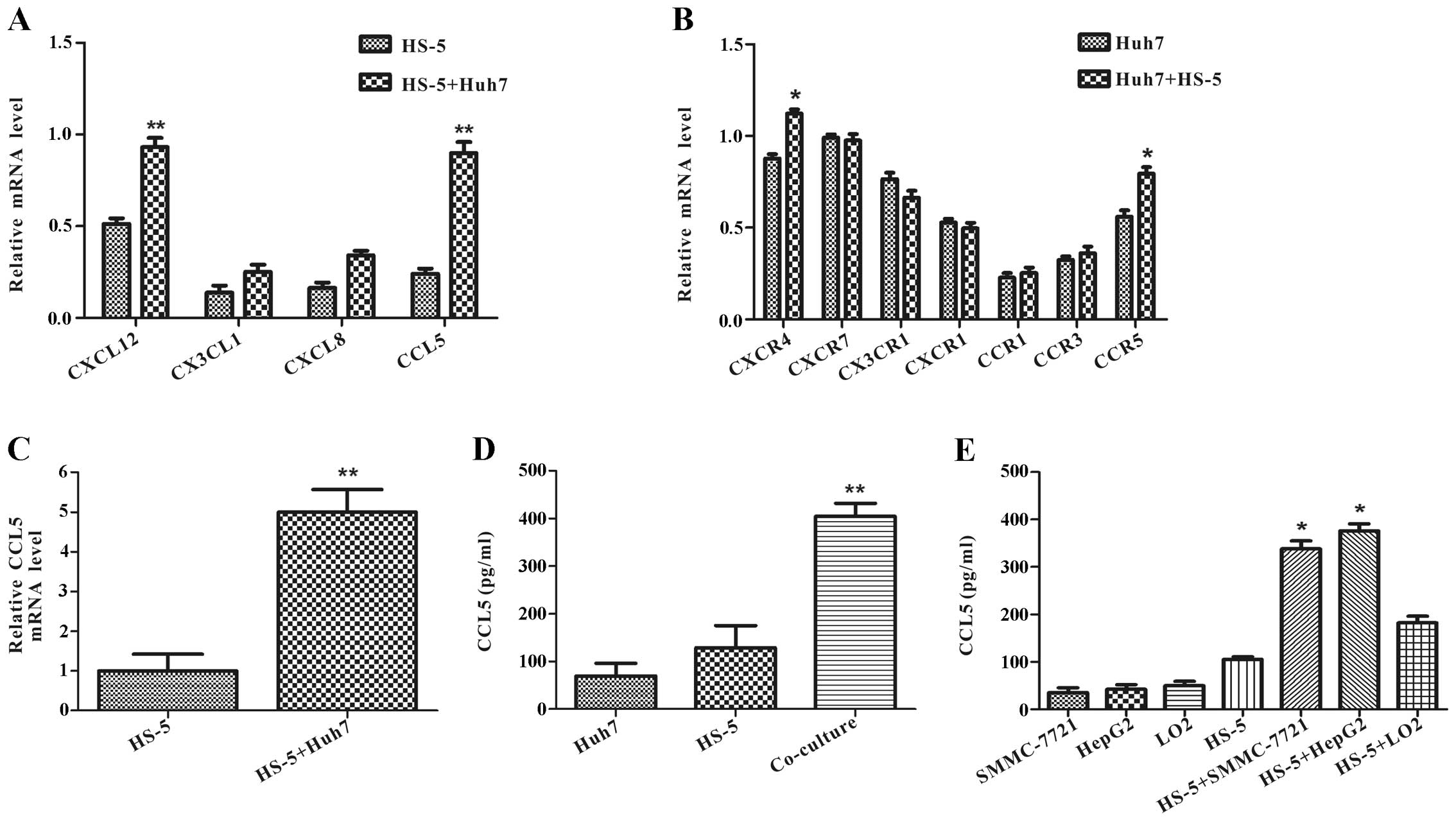

The molecular mechanisms of these pro-metastatic

impacts in tumor microenvironment are still unclear. To investigate

whether it is mediated by soluble factors secreted from HS-5 cells

in the capacity of migration and invasion, we identified several

chemokines by RT-PCR using RNA prepared from HS-5 cells co-cultured

with Huh7 cells or alone at day 3. It was found that CXCL12,

CX3CL1, CXCL8, CCL5 mRNA levels were upregulated in HS-5 cells

after co-culture, among which CCL5 showed the highest level of

increase (Fig. 5A). We also

examined these chemokine special receptor mRNAs in Huh7 cells.

RT-PCR assay showed that CXCR4 and CCR5 mRNA expression was

increased, and CX3CR1 mRNA was decreased in Huh7 cells co-cultured

with HS-5 cells compared with Huh7 cells alone at day 3 (Fig. 5B).

To confirm the change on CCL5 expression by qRT-PCR

and ELISA assay. qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated that CCL5 mRNA

expression had an approximate 5-fold increase in HS-5 cells

co-cultured with Huh7 cells compared with HS-5 cells alone at day 3

(Fig. 5C). In accordance with CCL5

mRNA level, ELISA assay revealed that co-culture specifically

increased CCL5 protein level more than 3-fold compared with the

secretion from Huh7 cells or HS-5 cells (Fig. 5D).

ELISA assay also verified that the change of CCL5

upregulation was not an accidental event with SMMC-7721 or HepG2 or

LO2 cells. It found that CCL5 protein levels were increased in HS-5

cells co-cultured with SMMC-7721 or HepG2 cells in different

degrees, but not with normal liver cells LO2 (Fig. 5E). The aforementioned data

illustrated that interaction with HCC and HS-5 cells could increase

CCL5 secretion in HS-5 cells.

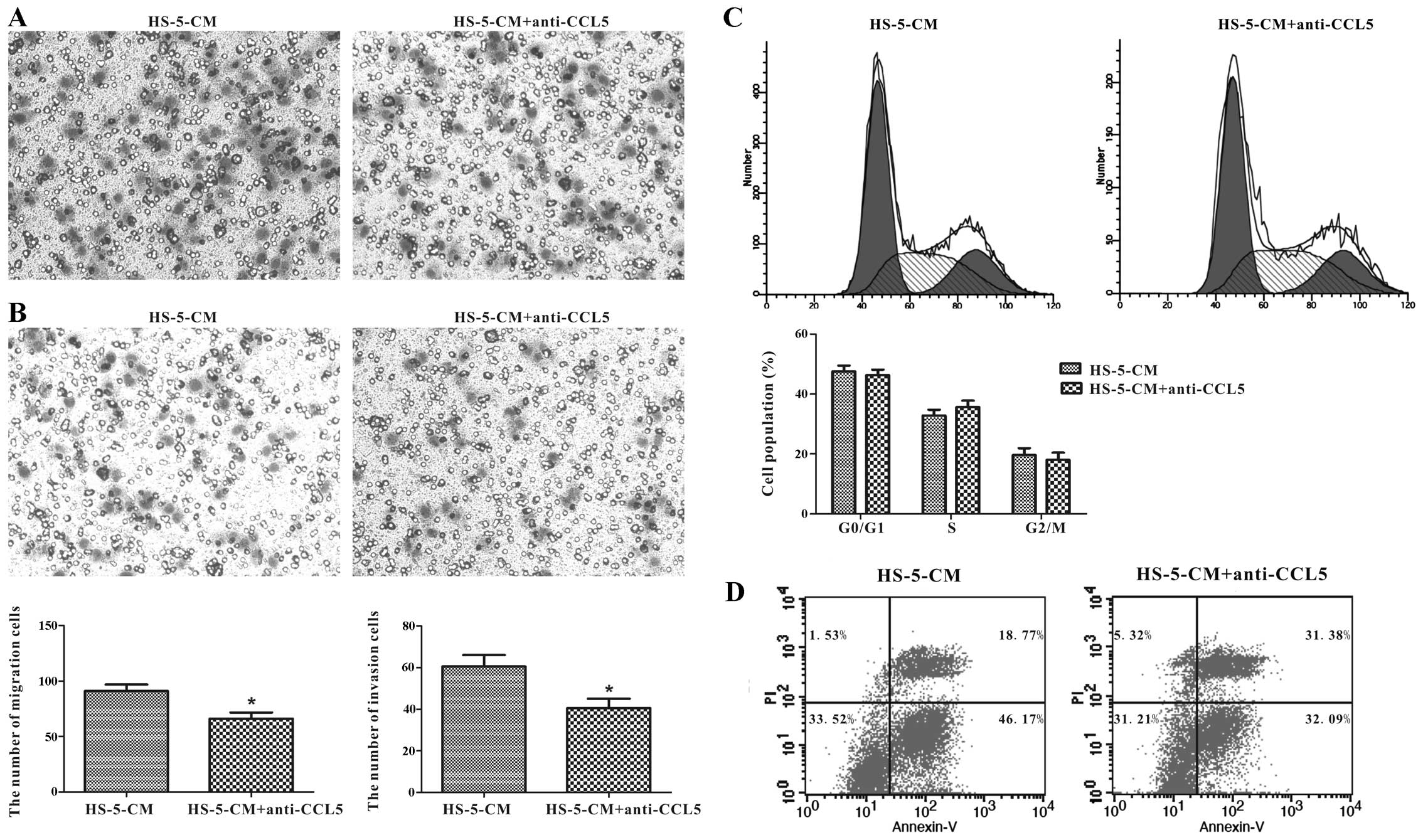

CCL5 secreted from HS-5 cells promotes

Huh7 cell migration and invasion in vitro

Whether HS-5 cells can modulate Huh7 cells

progression via CCL5 secretion remains unreported. We took a

loss-of-function approach to confirm its impact on Huh7 cells,

utilizing anti-CCL5 neutralizing antibody to HS-5-CM which was

cultured in Huh7 cells for 24 h. We tested the migration and

invasion abilities by Transwell assay, and it illustrated that

anti-CCL5 neutralizing antibody caused a decrease of 27.47% in

HS-5-CM-induced migration activity of Huh7 cells compared with the

control (Fig. 6A). Consistently,

Huh7 cell invasion ability was inhibited by 33.06% compared to the

control (Fig. 6B). However, not as

imagined, CCL5 downregulation in HS-5-CM did not overtly change

proliferation and apoptosis of Huh7 cells (Fig. 6C and D). It was thus possible that

CCL5 from HS-5-CM did not play a leading role in Huh7 cell

proliferation and apoptosis impact, but in migration and invasion

potency.

Effects of CCL5-secreted from HS-5 cells

on Huh7 cells via PI3K-Akt signaling pathway

The underlying mechanisms of the interaction with

MSCs and HCC within HCC micro-environment remain an enigma, so we

concentrated on the mechanisms of HS-5 cells inducing migration and

invasion of Huh7 cells. It has been reported that stimulation of

MSCs with certain chemokines causes the activation of Akt kinase

and ERK1/2 MAP kinase (31).

Therefore, we examined the potential changes of Huh7 cells in the

presence of HS-5 cells further. The transwell co-culture with HS-5

cells for 3 days, demonstrated by western blot analysis, revealed

that Huh7 cells had enhanced expression of p-Akt (Ser473) (Fig. 7A), but not p-ERK1/2 (Fig. 7B). The aforementioned data showed

that CCL5 expression was upregulated in HS-5 cells after co-culture

(Fig. 5C and D). Previous research

showed that CCL5 activated Gαi-PI3K-Akt and Gαi-MEK-ERK signaling

pathways (32). So it was

postulated that CCL5 is associated with the activation of p-Akt

(Ser473) and p-ERK1/2 in co-culture system. We applied anti-CCL5

antibody for 24 h to the co-culture system to evaluate the

hypothesis, the data showed the activation of p-Akt (Ser473) was

reduced by adding anti-CCL5 neutralizing antibody to Huh7 cells

co-cultured with HS-5 cells (Fig.

7A), however, there was no significant change in p-ERK1/2

(Fig. 7B). We next focused on CCL5

expression in response to p-Akt (Ser473) and p-ERK1/2 signaling

pathways. Before we investigated the roles of p-Akt (Ser473) and

p-ERK1/2 signaling pathways, western blot analysis demonstrated

PI3K and ERK1/2 specific inhibitors which, respectively, were

LY294002 (20 μM) and PD98059 (10 μM) could decrease

the expression of p-Akt (Ser473) and p-ERK1/2 (Fig. 7A and B). Transwell assay

illustrated that the migration and invasion of Huh7 cells induced

by HS-5-CM were partly reversed by treatment with LY294002 but not

by PD98059 (Fig. 7C and D). In

addition, ELISA assay demonstrated that LY294002 reduced the

secretion of CCL5 in co-culture system (Fig. 7E). Thus, our results illustrated

that CCL5 derived from HS-5 cells had a pivotal role in migration

and invasion of Huh7 cells via PI3K-Akt signaling pathway.

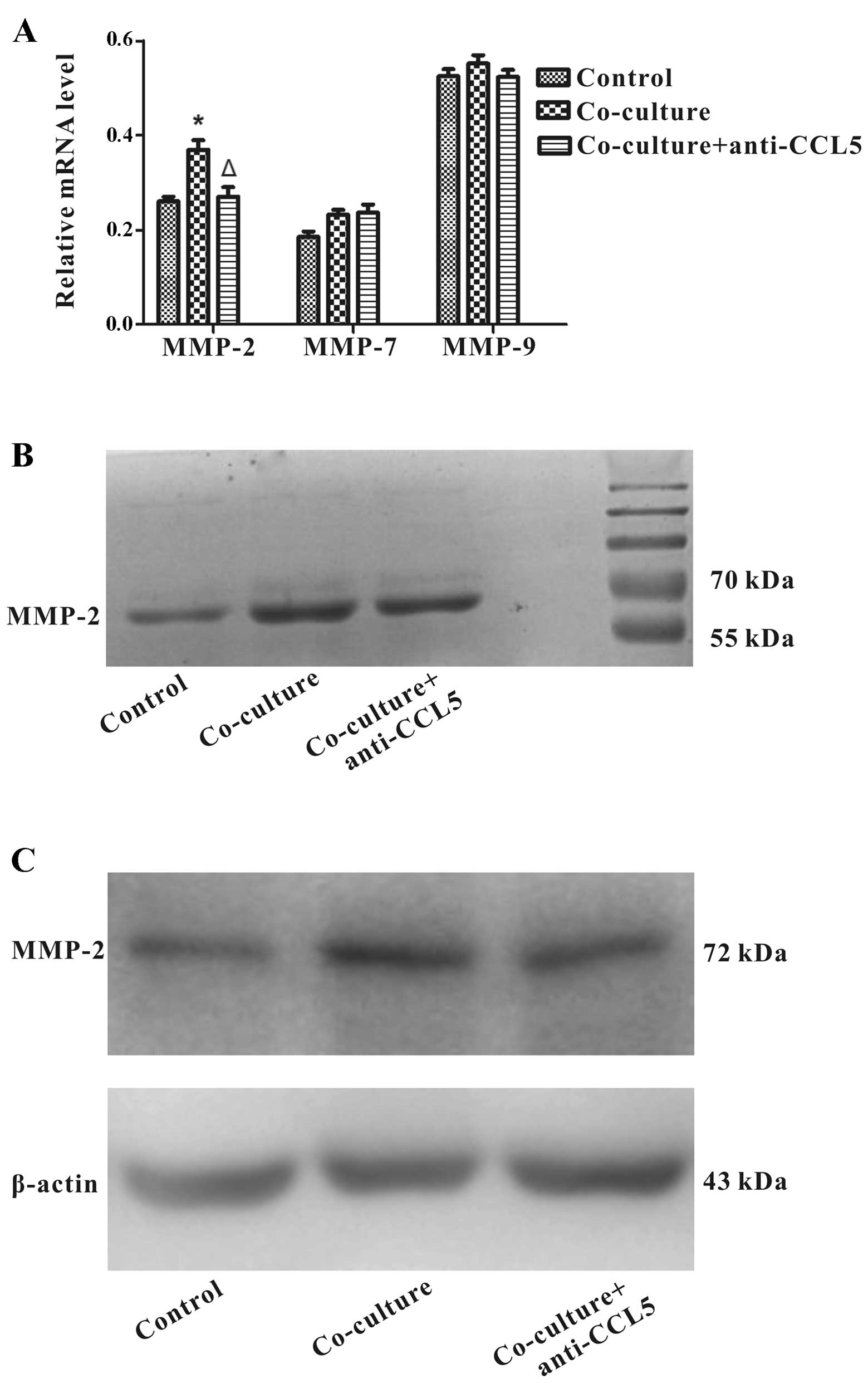

CCL5 downregulation from HS-5 cells

decreases MMP-2 expression in Huh7 cells

Cell movement is involved in the proteolytic

activity of MMPs, which regulate the dynamic ECM (extracellular

matrix)-cell and cell-cell interaction during migration (33). High expression of MMPs is related

to HCC progression (34,35). We investigated whether CCL5

regulated the levels of MMP-2, MMP-7 and MMP-9 in Huh7 cells

co-cultured with HS-5 cells. RT-PCR analysis showed that MMP-2

expression was up-regulated in Huh7 cells co-cultured with HS-5

cells at day 3, extraordinary, MMP-2 mRNA was downregulated through

the addition of anti-CCL5 neutralizing antibody. Nonetheless, the

expression of MMP-7 and MMP-9 mRNAs remained significantly

unchanged (Fig. 8A). To further

characterize the effect of CCL5 in MMP expression of Huh7 cells, we

applied gelatin zymography analysis to determine expression and

enzymatic activities of MMP-2 and MMP-9. The results revealed that

treatment of anti-CCL5 neutralizing antibody pointed to a decrease

in MMP-2 upregulation of Huh7 cells co-cultured with HS-5 cells,

whereas MMP-9 was not detected (Fig.

8B). Consistently, western blot assay confirmed that anti-CCL5

neutralizing antibody could reduce MMP-2 protein upregulation

mediated by HS-5 cells in Huh7 cells (Fig. 8C). The data indicated that CCL5

downregulation from HS-5 cells decreased MMP-2 expression in Huh7

cells.

Discussion

HCC invasion and metastasis are very strongly

related to cancer patient survival, but the detailed mechanisms are

still unknown (36). Advanced HCC

patients presenting with bone metastases are different from breast

and prostate cancer patients, particularly in liver function

impairment, prognosis and available effective treatments (37). Cirrhosis is an independent

prognostic factor for osteoporosis (38). Bone marrow is the most common

source of MSCs, which are found to take part in tumor

microenvironment that mediates tumor cell progress. However,

crosstalk of the tumor-MSCs is complicated, the controversy on the

effects of MSCs on the tumor cell progression remains to be

debated, especially in HCC. Herein, we adopted HS-5-CM to eliminate

the interaction with HCC cells, and it demonstrated that HS-5 cells

could promote proliferation, migration and invasion of Huh7 cells

in vitro, and the increase of proliferation was verified by

the in vivo results. Our results are consistent with a large

proportion of research (16,17,20).

However, the tumor metastasis in liver and lung regions were not

found, demonstrating that Huh7 cell invasion ability is limited

in vivo. Despite the above, some reports stated that MSCs

could inhibit HCC cell growth (22,39).

It is proposed that the time of MSCs introduction into tumors might

be a critical factor for the contradicting results (9). In this study, we consider that MSCs

are helpful for HCC progression.

MSC secretions include a complex mixture of

cytokines, growth factors and chemokines, which have an influence

on cancer cell migration and invasion. In this study, the data

determined that in co-culture with Huh7 cells, HS-5 cells expressed

an increased level of CCL5. To circumvent variability in cell-cell

interaction subsequent experiments were done using conditioned

medium from the ‘co-culture’ cell lines, and it was shown to

consistently alter the CCL5 level. To our knowledge, chemokines and

receptors play a number of non-redundant roles in tumor

progression. Besides, some reports indicate that CCL5 is an

effective inducer of tumor cell migration and invasion, such as in

breast, colorectal, osteosarcoma and prostate tumor cells, acting

through paracrine and autocrine manners (40–44).

It was demonstrated that stroma-derived CCL5 was particularly

important in inducing pro-malignancy impact in CCR5-expressing

breast cancer cells (12).

However, in tumor microenvironment, whether HS-5 cells mediated

CCL5 plays a pivotal role in HCC migratory and invasion, has not

been extensively studied. We found that Huh7 cells revealed a

higher level of CCR5 mRNA than CCR1 and CCR3, and an obvious

increase in CCR5 mRNA after co-culture. Furthermore, a recent

report determined that CCR5 was involved to HCC inflammation

(45). CCR5 is more important than

CCR1 and CCR3 in HCC progress in our study. Anti-CCL5

neutralization antibody decreased the migration and invasion of

Huh7 cells mediated by HS-5-CM. The results indicated that the

CCL5/CCR5 axis was associated with migration and invasion of Huh7

cells in tumor micro-environment. It cannot be denied that other

cytokines play a pivotal role of malignant progression like CXCL12

promoting tumor cell proliferation and survival via paracrine and

auto-crine mechanisms (46,47).

It was proposed that CXCL12 could promote HCC cells migration

(48). Nevertheless, in mimicking

HCC microenvironment, it cannot be ignored that CCL5-secreted from

MSCs is a critical factor in Huh7 cell migration and invasion.

Activation of PI3K contributes to invasion and

metastasis of HCC (49). ERK1/2

pathway is connected with the migratory or invasive behavior of a

variety of malignancies (50).

Thus, whether the progression of HCC induced by MSCs is involved in

the PI3K/Akt and ERK1/2 signaling pathways has not been yet

established. In particular, we demonstrated that the PI3K inhibitor

LY294002 antagonized enhancement in migration and invasion of Huh7

cells, and also reduced CCL5 secretion. However, co-culture did not

activate the p-ERK1/2 signaling pathway and ERK1/2 specific

inhibitor PD98059 did not reduce the mobility and invasiveness of

Huh7 cells. It is possible that ERK1/2 signaling pathway regulates

another biological function in HCC microenvironment. It is

conceivable that other signaling pathways may synergistically or

antagonistically regulate the HCC progress. Our data indicated that

PI3K/Akt signaling pathway could play an important part in

CCL5-mediated migration and invasion of Huh7 cells.

MMPs play a key role in cancer cell invasion. Some

data showed that the expression of MMP-2 increased in hepatic

fibrosis (51), others reported

that certain cytokines could increase MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion in

human sarcoma cells (52). Xiang

et al showed that MMP-2 was an independent prognostic factor

for lymph node metastasis in HCC (53). Previous studies showed that CCL5

promoted the expression of MMP-9 in tumor cells (44,54,55).

In this study, we demonstrated that HS-5 cells did not elevate

MMP-9 expression but MMP-2 expression in Huh7 cells. The results

suggest that anti-CCL5 neutralization antibody could depress the

secretion of MMP-2 in Huh7 cells. Therefore, MMP-2 may be a

CCL5-responsive mediator, and it causes the degradation of ECM,

which may lead to subsequent HCC migration and metastasis.

In conclusion, the current observations indicate

that HS-5 cells can promote the proliferation, migration and

invasion, and inhibit apoptosis of Huh7 cells. Exocrine CCL5

secreted from MSCs promotes migration and invasion of Huh7 cells

via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, and accompanies the MMP-2

upregulation. Hence, CCL5 may be an important factor in HCC with

bone metastases.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Tongchuan He

(University of Chicago) for the gift of human hepatocellular

carcinoma cell lines and normal human liver cell lines. This study

was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China

(NSFC 31200971), National Ministry of Education Foundation of China

(20115503110009) and the 973 Program of the Ministry of Science and

Technology of China (2011CB707906).

References

|

1.

|

Yang JD and Roberts LR: Hepatocellular

carcinoma: A global view. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 7:448–458.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Ma W, Wong CC, Tung EK, Wong CM and Ng IO:

RhoE is frequently down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

and suppresses HCC invasion through antagonizing the

Rho/Rho-kinase/myosin phosphatase target pathway. Hepatology.

57:152–161. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Ho CL, Chen S, Yeung DW and Cheng TK:

Dual-tracer PET/CT imaging in evaluation of metastatic

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 48:902–909. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Natsuizaka M, Omura T, Akaike T, et al:

Clinical features of hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic

metastases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 20:1781–1787. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Xiang ZL, Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, et al:

Chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma

patients increases the risk of bone metastases and poor survival.

BMC Cancer. 9:1762009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Paget S: The distribution of secondary

growths in cancer of the breast. 1889. Cancer Metastasis Rev.

8:98–101. 1989.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Chung LW, Baseman A, Assikis V and Zhau

HE: Molecular insights into prostate cancer progression: the

missing link of tumor microenvironment. J Urol. 173:10–20. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Chackal-Roy M, Niemeyer C, Moore M and

Zetter BR: Stimulation of human prostatic carcinoma cell growth by

factors present in human bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 84:43–50.

1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Klopp AH, Gupta A, Spaeth E, Andreeff M

and Marini F III: Concise review: Dissecting a discrepancy in the

literature: do mesenchymal stem cells support or suppress tumor

growth? Stem Cells. 29:11–19. 2011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Maestroni GJ, Hertens E and Galli P:

Factor(s) from nonmacrophage bone marrow stromal cells inhibit

Lewis lung carcinoma and B16 melanoma growth in mice. Cell Mol Life

Sci. 55:663–667. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Kucerova L, Matuskova M, Hlubinova K,

Altanerova V and Altaner C: Tumor cell behaviour modulation by

mesenchymal stromal cells. Mol Cancer. 9:1292010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, et al:

Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer

metastasis. Nature. 449:557–563. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Lin JT, Wang JY, Chen MK, et al: Colon

cancer mesenchymal stem cells modulate the tumorigenicity of colon

cancer through interleukin 6. Exp Cell Res. 319:2216–2229. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Khakoo AY, Pati S, Anderson SA, et al:

Human mesenchymal stem cells exert potent antitumorigenic effects

in a model of Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Exp Med. 203:1235–1247.

2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Zhang C, Soori M, Miles FL, et al:

Paracrine factors produced by bone marrow stromal cells induce

apoptosis and neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer

cells. Prostate. 71:157–167. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Hernanda PY, Pedroza-Gonzalez A, van der

Laan LJ, et al: Tumor promotion through the mesenchymal stem cell

compartment in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Carcinogenesis.

34:2330–2340. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Mizuguchi T, Hui T, Palm K, et al:

Enhanced proliferation and differentiation of rat hepatocytes

cultured with bone marrow stromal cells. J Cell Physiol.

189:106–119. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Jing Y, Han Z, Liu Y, et al: Mesenchymal

stem cells in inflammation microenvironment accelerates

hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis by inducing

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS One. 7:e432722012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19.

|

Li GC, Ye QH, Dong QZ, Ren N, Jia HL and

Qin LX: Mesenchymal stem cells seldomly fuse with hepatocellular

carcinoma cells and are mainly distributed in the tumor stroma in

mouse models. Oncol Rep. 29:713–719. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Li GC, Ye QH, Xue YH, et al: Human

mesenchymal stem cells inhibit metastasis of a hepatocellular

carcinoma model using the MHCC97-H cell line. Cancer Sci.

101:2546–2553. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Niess H, Bao Q, Conrad C, et al: Selective

targeting of genetically engineered mesenchymal stem cells to tumor

stroma microenvironments using tissue-specific suicide gene

expression suppresses growth of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg.

254:767–775. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22.

|

Qiao L, Xu Z, Zhao T, et al: Suppression

of tumorigenesis by human mesenchymal stem cells in a hepatoma

model. Cell Res. 18:500–507. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Ho IA, Toh HC, Ng WH, et al: Human bone

marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells suppress human glioma growth

through inhibition of angiogenesis. Stem Cells. 31:146–155. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Sahin H, Trautwein C and Wasmuth HE:

Functional role of chemokines in liver disease models. Nat Rev

Gastroenterol Hepatol. 7:682–690. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Makinoshima H and Dezawa M: Pancreatic

cancer cells activate CCL5 expression in mesenchymal stromal cells

through the insulin-like growth factor-I pathway. FEBS Lett.

583:3697–3703. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Luther SA and Cyster JG: Chemokines as

regulators of T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2:102–107. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Charni F, Friand V, Haddad O, et al:

Syndecan-1 and syndecan-4 are involved in RANTES/CCL5-induced

migration and invasion of human hepatoma cells. Biochim Biophys

Acta. 1790:1314–1326. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Sutton A, Friand V, Papy-Garcia D, et al:

Glycosaminoglycans and their synthetic mimetics inhibit

RANTES-induced migration and invasion of human hepatoma cells. Mol

Cancer Ther. 6:2948–2958. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Liou JM, Lin JT, Huang SP, et al:

RANTES-403 polymorphism is associated with reduced risk of gastric

cancer in women. J Gastroenterol. 43:115–123. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Kondo T, Ito F, Nakazawa H, Horita S,

Osaka Y and Toma H: High expression of chemokine gene as a

favorable prognostic factor in renal cell carcinoma. J Urol.

171:2171–2175. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Honczarenko M, Le Y, Swierkowski M, Ghiran

I, Glodek AM and Silberstein LE: Human bone marrow stromal cells

express a distinct set of biologically functional chemokine

receptors. Stem Cells. 24:1030–1041. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32.

|

Tyner JW, Uchida O, Kajiwara N, et al:

CCL5-CCR5 interaction provides antiapoptotic signals for macrophage

survival during viral infection. Nat Med. 11:1180–1187. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Bao M, Chen Z, Xu Y, et al: Sphingosine

kinase 1 promotes tumour cell migration and invasion via the

S1P/EDG1 axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 32:331–338.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34.

|

Palagyi A, Neveling K, Plinninger U, et

al: Genetic inactivation of the Fanconi anemia gene FANCC

identified in the hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HuH-7 confers

sensitivity towards DNA-interstrand crosslinking agents. Mol

Cancer. 9:1272010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35.

|

Shi F, Shi M, Zeng Z, et al: PD-1 and

PD-L1 upregulation promotes CD8(+) T-cell apoptosis and

postoperative recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Int

J Cancer. 128:887–896. 2011.

|

|

36.

|

Chen J, Liu WB, Jia WD, et al:

Overexpression of mortalin in hepatocellular carcinoma and its

relationship with angiogenesis and epithelial to mesenchymal

transition. Int J Oncol. 44:247–255. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37.

|

Montella L, Addeo R, Palmieri G, et al:

Zoledronic acid in the treatment of bone metastases by

hepatocellular carcinoma: a case series. Cancer Chemother

Pharmacol. 65:1137–1143. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38.

|

Crawford BA, Kam C, Pavlovic J, et al:

Zoledronic acid prevents bone loss after liver transplantation: a

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med.

144:239–248. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39.

|

Lu YR, Yuan Y, Wang XJ, et al: The growth

inhibitory effect of mesenchymal stem cells on tumor cells in vitro

and in vivo. Cancer Biol Ther. 7:245–251. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40.

|

Wang SW, Wu HH, Liu SC, et al: CCL5 and

CCR5 interaction promotes cell motility in human osteosarcoma. PLoS

One. 7:e351012012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41.

|

Cambien B, Richard-Fiardo P, Karimdjee BF,

et al: CCL5 neutralization restricts cancer growth and potentiates

the targeting of PDGFRβ in colorectal carcinoma. PLoS One.

6:e288422011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42.

|

Vaday GG, Peehl DM, Kadam PA and Lawrence

DM: Expression of CCL5 (RANTES) and CCR5 in prostate cancer.

Prostate. 66:124–134. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43.

|

Gallo M, De Luca A, Lamura L and Normanno

N: Zoledronic acid blocks the interaction between mesenchymal stem

cells and breast cancer cells: implications for adjuvant therapy of

breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 23:597–604. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44.

|

Long H, Xie R, Xiang T, et al: Autocrine

CCL5 signaling promotes invasion and migration of CD133+

ovarian cancer stem-like cells via NF-κB-mediated MMP-9

upregulation. Stem Cells. 30:2309–2319. 2012.

|

|

45.

|

Barashi N, Weiss ID, Wald O, et al:

Inflammation-induced hepatocellular carcinoma is dependent on CCR5

in mice. Hepatology. 58:1021–1030. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46.

|

Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, et al:

Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas

promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12

secretion. Cell. 121:335–348. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47.

|

Mo W, Chen J, Patel A, et al: CXCR4/CXCL12

mediate autocrine cell-cycle progression in NF1-associated

malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Cell. 152:1077–1090.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48.

|

Liu H, Pan Z, Li A, et al: Roles of

chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) and chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) in

metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Mol Immunol.

5:373–378. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49.

|

Li X, Yang Z, Song W, et al:

Overexpression of Bmi-1 contributes to the invasion and metastasis

of hepatocellular carcinoma by increasing the expression of matrix

metalloproteinase (MMP)-2, MMP-9 and vascular endothelial growth

factor via the PTEM/PI3K/Akt pathway. Int J Oncol. 43:793–802.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50.

|

Suthiphongchai T, Promyart P, Virochrut S,

Tohtong R and Wilairat P: Involvement of ERK1/2 in invasiveness and

metastatic development of rat prostatic adenocarcinoma. Oncol Res.

13:253–259. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51.

|

Diaz-Gil JJ, Garcia-Monzon C, Rua C, et

al: The anti-fibrotic effect of liver growth factor is associated

with decreased intrahepatic levels of matrix metalloproteinases 2

and 9 and transforming growth factor beta 1 in bile ductligated

rats. Histol Histopathol. 23:583–591. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52.

|

Roomi MW, Kalinovsky T, Rath M and

Niedzwiecki A: In vitro modulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 in

pediatric human sarcoma cell lines by cytokines, inducers and

inhibitors. Int J Oncol. 44:27–34. 2014.

|

|

53.

|

Xiang ZL, Zeng ZC, Fan J, et al: Gene

expression profiling of fixed tissues identified hypoxia-inducible

factor-1α, VEGF, and matrix metalloproteinase-2 as biomarkers of

lymph node metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res.

17:5463–5472. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54.

|

Wang YH, Dong YY, Wang WM, et al: Vascular

endothelial cells facilitated HCC invasion and metastasis through

the Akt and NF-κB pathways induced by paracrine cytokines. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 32:512013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55.

|

Gao J, Ding F, Liu Q and Yao Y: Knockdown

of MACC1 expression suppressed hepatocellular carcinoma cell

migration and invasion and inhibited expression of MMP2 and MMP9.

Mol Cell Biochem. 376:21–32. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|