Introduction

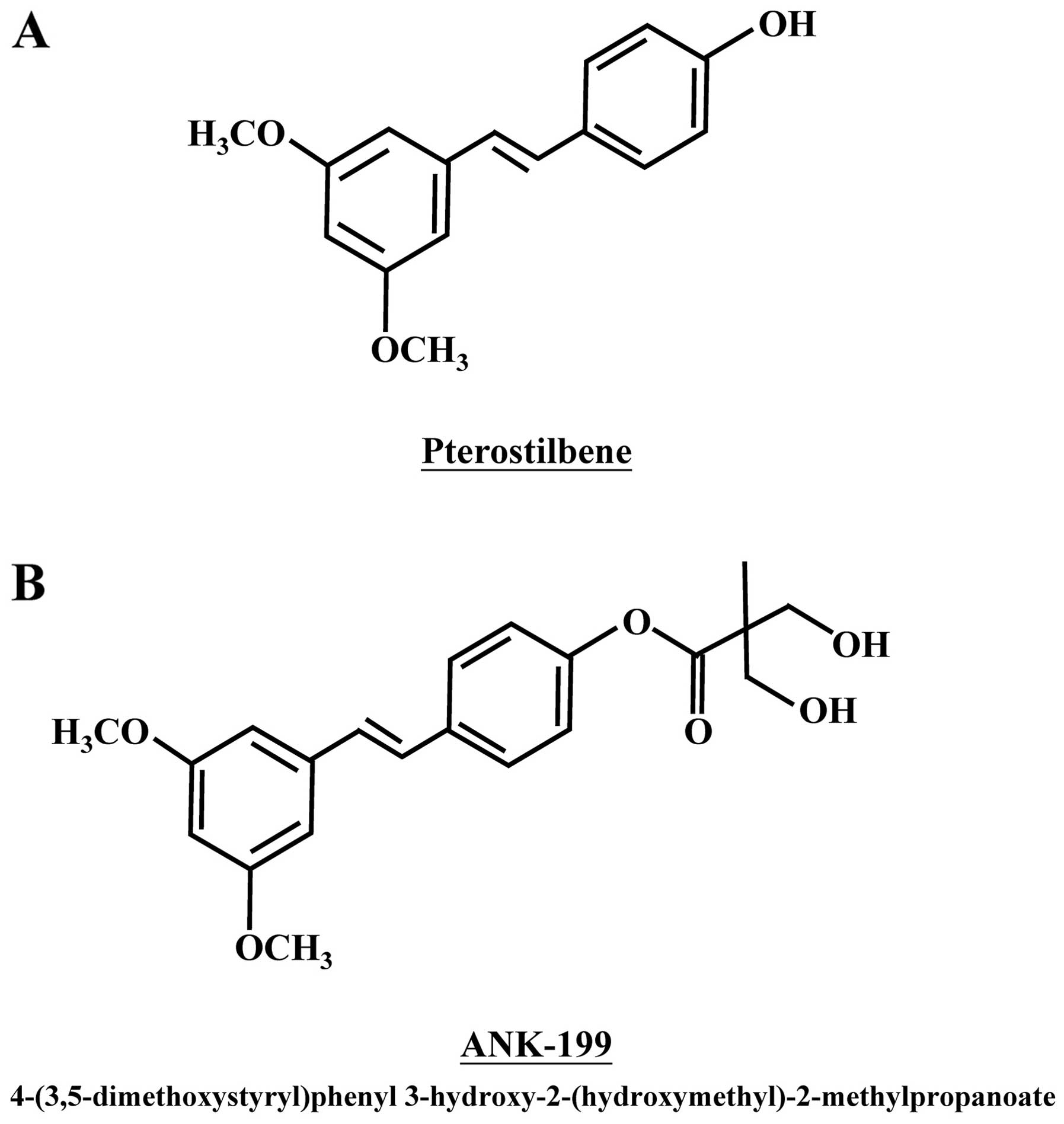

Pterostilbene, a natural stilbenoid compound of

phenolic phytoalexin analogue, is found in narra tree, grape and

blueberries (Fig. 1A) (1–4). It

possesses many different pharmacological and biologic activities,

such as anticancer activity with low intrinsic toxicity (4–6),

anti-inflammatory properties (7–9),

anti-oxidative effect (2),

regulation of neutrophil function (10,11)

and protection against free radical-mediated oxidative damage

(12–14). The anticancer activity of

pterostilbene has drawn the most attention among of them so far

(1,4–6). As

reported in previous studies, pro-apoptosis (4,15,16),

pro-autophagy (17–19), telomerase inhibition (20), DNA damage (12,13,15),

anti-angiogenesis (21),

anti-metastasis (4,21) and immuno-stimulatory effects

(10,11) are possible mechanisms responsible

for its anticancer activity.

Pterostilbene is able to induce apoptosis in many

different cancer cell lines, such as pancreatic cancer cells

(22,23), breast cancer MCF-7 cells (20,24,25),

docetaxel-induced multiple drug resistance (MDR) lung cancer cells

(26), osteosarcoma cells

(27), prostate cancer PC-3 and

LNCaP cells (28,29), leukemia K562 cells (30,31),

MDR and BCR-ABL-expressing leukemia cells (30,31),

colon cancer cells (32–34), hepatocellular carcinoma cells

(35,36) and gastric carcinoma cells (7,15).

On the other hand, it is also reported that autophagic death can be

triggered by pterostilbene in leukemia HL60 (17) and MOLT4 cells (37), lung cancer cells (18,32,38),

colon cancer HT29 cells (32),

breast cancer MCF-7 cells (39),

bladder cancer cells (17,40) and vascular endothelial cells

(41). In addition, pterostilbene

is capable of inhibiting tumorigenesis and metastasis with minor

toxicity in vivo (4,22,38).

It is safe in doses up to 250 mg/day in human clinical trial, and

deserves further investigation as a potential anticancer agent

(42). A novel pterostilbene

derivative, ANK-199, was therefore designed and synthesized by our

group (Fig. 1B).

Chewing the mixtures of betel leaf and areca nut is

a popular custom in many South and Southeast Asia countries. It is

a high risk factor for oral cavity carcinoma (43,44),

and is the 4th most common cause of cancer death in Taiwanese males

(45). Natural product with high

anticancer activity and low toxicity, like pterostilbene, appears

to be an ideal candidate to prevent or treat oral cancer, as it can

directly contact with human oral mucosa without intravenous

administration or surgery (22).

The anti-oral cancer activity of pterostilbene derivative, ANK-199,

was first investigated in this study. Both normal human oral cell

lines and cisplatin-resistant CAR human oral cancer cell lines were

used. Here, we report the cytotoxic effect and anticancer mechanism

of ANK-199 in human oral cancer CAR cells.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 3-methyladenine (3-MA),

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

(MTT), monodansyl cadaverine (MDC), cisplatin, β-actin antibody,

and Tween-20 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corp. (St. Louis, MO,

USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS), L-glutamine,

penicillin/streptomycin, Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM),

acridine orange (AO), and trypsin-EDTA were purchased from Life

Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The primary antibodies

(anti-Atg5, anti-Atg7, anti-Atg12, anti-Atg14, anti-Atg16L1,

anti-beclin 1, anti-PI3K class III, anti-LC3-II, and anti-Rubicon)

were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA),

and the horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary

antibodies against rabbit or mouse immunoglobulin for western blot

analysis were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa

Cruz, CA, USA). ANK-199 [4-(3,5-dimethoxystyryl)phenyl

3-hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-methylpropanoate] was synthesized by

Dr Sheng-Chu Kuo.

Cell culture

The human oral cancer cell line CAL 27 was obtained

from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA,

USA). CAR, a cisplatin-resistant cell line, was established by

clonal selection of CAL 27 using 10 cycles of 1 passage treatment

with 10–80 μM of cisplatin followed by a recovery period of another

passage. CAR cells were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10%

FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin, 2 mM L-glutamine

and 80 μM cisplatin. Human normal gingival fibroblasts cells (HGF)

and human normal oral keratinocyte cells (OK) were kindly provided

by Dr Tzong-Ming Shieh (Department of Dental Hygiene, China Medical

University). HGF and OK cells were cultivated in DMEM as previously

described for our study (45).

Cell viability and morphological

examination

CAR cells (1×104 cells) in a 96-well

plate were incubated with 0, 25, 50, 75 and 100 μM of ANK-199 for

24, 48 and 72 h. For incubation with the autophagy inhibitor, cells

were pretreated with 3-MA (10 mM) for 1 h, followed by treatment

with or without ANK-199 (50 and 75 μM) for 48 h. After washing the

cells, DMEM containing MTT (0.5 mg/ml) of was added to detect

viability as previously described (6). The cell viability was expressed as %

of the control. Cell morphological examination of autophagic

vacuoles was determined utilizing a phase-contrast microscope

(46,47).

Observation of autophagic vacuoles by MDC

and acidic vesicular organelles (AVO) with AO staining

CAR cells were seeded on sterile coverslips in

tissue culture plates with a density of 5×104 cells/per

coverslip. After 0, 50, 75 μM of ANK-199 treatment for 24 h, cells

were stained with either 1 μg/ml AO or 0.1 mM MDC at 37°C for 10

min. The occurrece of autophagic vacuoles and AVO were immediately

observed under fluorescence microscopy (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA)

(46–48).

Autophagy assay by LC3B-GFP imaging and

nuclear stain

The induction of autophagy was detected with the

Premo™ Autophagy Sensor (LC3B-GFP) BacMam 2.0 kit (Molecular

Probes/Life Technologies). CAR cells were seeded on sterile

coverslips in tissue culture plates with a density of

1×104 cells/per coverslip. After CAR cells were

transfected with LC3B-GFP in accordance with the manufacturer’s

protocol, cells were treated with 0, 50 and 75 μM of ANK-199 for 24

h. Cells were then fixed on ice with 4% paraformaldehyde, and the

slides were mounted and analyzed by a fluorescence microscope.

After treatments, cells were stained with

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Molecular Probes/Life

Technologies) and photographed using a fluorescence microscope

(46,47,49).

Western blot analysis

CAR cells (1×107 cells/75-T flask) were

treated with ANK-199 (50 and 75 μM) for 48 h. At the end of

incubation, the total proteins were prepared, and the protein

concentration was measured by using a BCA assay kit (Pierce

Chemical, Rockford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of cell lysates were

run on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and further

employed by immunoblotting as described by Lin et al

(46).

Real-time PCR analysis

CAR cells at a density of 5×106 in T75

flasks were incubated with or without 50 and 75 μM of ANK-199 for

24 h. Cells were collected, and total RNA was extracted by the

Qiagen RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA). Each RNA

sample was individually reverse-transcribed using the High Capacity

cDNA Reverse Transcription kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City,

CA, USA). Quantitative PCR was assessed for amplifications with 2X

SYBR-Green PCR Master mix (Applied Biosystems), as well as forward

and reverse primers for Atg7, Atg12, beclin 1

and LC3-II gene. (Human ATG7-F-CAGCAGTGACGATCGGATGA; human

ATG7-R-GACGGGAAGGACATTATCAAACC; human

ATG12-F-TGTGGCCTCAGAACAGTTGTTTA; human

ATG12-R-CGCCTGAGACTTGCAGTAATGT; human

BECN1-F-GGATGGTGTCTCTCGCAGATTC; human BECN1-R-GGTGCCGCCATCAGATG;

human LC3-II-F-CCGACCGCTGTAAGGAGGTA; human

LC3-II-R-AGGACGGGCAGCTGCTT) Applied Biosystems 7300 Real-Time PCR

System was run in triplicate, and each value was expressed in the

comparative threshold cycles (CT) method for the housekeeping gene

GAPDH.

cDNA microarray analysis

CAR cells (5×106 per T75 flask) were

incubated with or without 75 μM of ANK-199 for 24 h. Cells were

scraped and collected by centrifugation. The total RNA was

subsequently isolated as stated above, and the purity was assessed

at 260 and 280 nm using a Nanodrop (ND-1000; Labtech

International). Each sample (300 ng) was amplified and labeled

using the GeneChip WT Sense Target Labeling and Control Reagents

(900652) for Expression Analysis. Hybridization was performed

against the Affymetrix GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST array. The arrays

were hybridized for 17 h at 45°C and 60 rpm. Arrays were

subsequently washed (Affymetrix Fluidics Station 450), stained with

streptavidin-phycoerythrin (GeneChip Hybridization, Wash, and Stain

Kit, 900720), and scanned on an Affymetrix GeneChip Scanner 3000.

Resulting data were analyzed by using Expression Console software

(Affymetrix) with default RMA parameters. Genes regulated by

ANK-199 were determined with a 1.5-fold change. For detection of

significantly over-represented GO biological processes, the DAVID

functional annotation clustering tool (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) was used (DAVID

Bioinformatics Resources 6.7). Enrichment was determined at DAVID

calculated Benjamini value <0.05. Significance of overexpression

of individual genes was determined (50).

Statistical analysis

All the statistical results were expressed as the

mean ± SEM of triplicate samples. Statistical analyses of data were

done using one-way ANOVA followed by Student’s t-test, and

*p<0.05 and ***p<0.001 were considered

significant.

Results

ANK-199 exhibits cytotoxicity and

inhibits viable CAR cells

CAR cells were treated with different concentrations

of ANK-199 for 24, 48 and 72 h. ANK-199 concentration- and

time-dependently decreased cell viability of CAR cells (Fig. 2A). The half maximal inhibitory

concentration (IC50) for a 24, 48 and 72-h treatment of

ANK-199 in CAR cells were 106.21±3.21, 73.25±4.20 and 32.58±2.39

μM, respectively. To investigate whether the cell death was

mediated through apoptosis by ANK-199, cells were treated with 50

and 75 μM ANK-199 for 48 h. The appearance of DNA fragmentation was

not observed (data not shown), suggesting that ANK-199 was unable

to induce apoptosis in CAR cells. As shown in Fig. 2B, ANK-199 was able to induce the

formation of autophagic vacuoles in CAR cells in a time-dependent

manner in the presence of 50 μM ANK-199 for 24, 48 and 72 h. This

result implies that autophagic cell death plays a pivotal role in

ANK-199-induced cell death. However, no viability impact and

morphological trait change was observed in ANK-199-treated HGF and

OK cells, suggesting that ANK-199 has an extremely low toxicity in

normal oral cell lines. In accordance with this observation, the

IC50 value of HGF and OK cells is greater than 100 μM

(Fig. 3A and B). In short,

ANK-199-induced cell death of CAR cells is mediated through

autophagic death, rather than apoptosis.

ANK-199 induces autophagic cell death in

CAR cells

To further confirm the formation of autophagosome

vesicles in ANK-199-treated CAR cells, the autophagic cell death

caused by ANK-199 was monitored by using MDC staining, a popular

fluorescent marker that preferentially accumulates in autophagic

vacuoles (46,48). After cells were treated with 50 and

75 μM of ANK-199 for 48 h, autophagic vacuoles were easily observed

under fluorescence microscopy (Fig.

4A). The intensity of MDC staining was directly proportional to

the concentration of ANK-199. The ANK-199-triggered autophagic cell

death was also examined by using AO staining. In Fig. 4B, AO staining of ANK-199-treated

CAR cells clearly showed the presence of AVOs within the cytoplasm

compared to control. Microtubule-associated protein 1 light-chain 3

(LC3) is an autophagic membrane marker for the detection of early

autophagosome formation (46,49).

The LC3 distribution in ANK-199-treated CAR cells was also

investigated. A more punctate pattern of LC3B-GFP was observed in

ANK-199 treated cells (Fig. 4C).

The occurrence of DNA condensation was also investigated in the

presence of 50 and 75 μM ANK-199 for 24 h. No significant change

was observed in ANK-199-treated CAR cells under microscope, which

means that ANK-199-induced cell death triggered by apoptosis is

quite unlikely (Fig. 4D). Again,

all of the above results support that ANK-199-induced cell death in

CAR cells is mediated through the induction of autophagic death

instead of apoptosis.

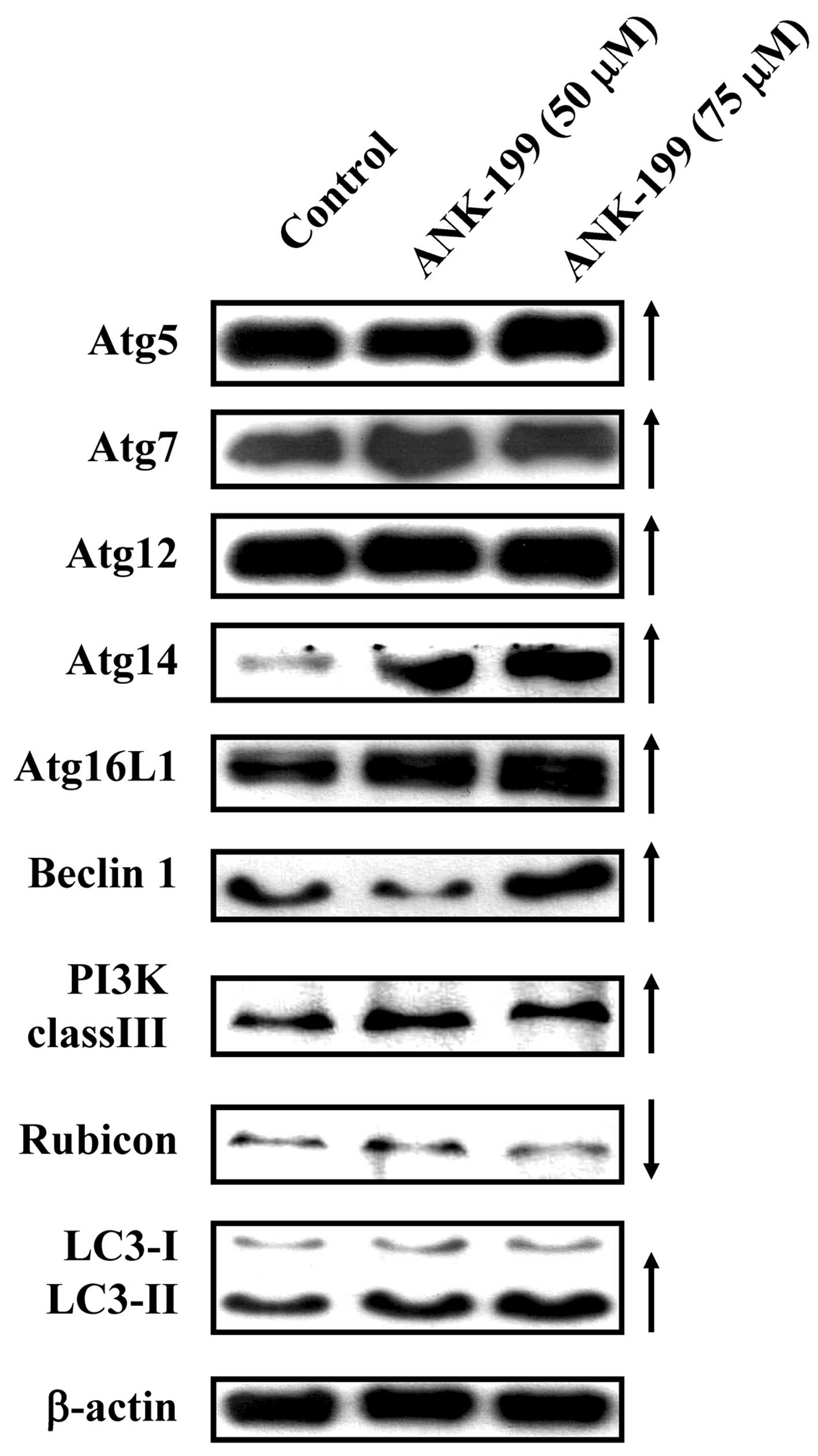

ANK-199 upregulates the

autophagy-associated protein levels in CAR cells

The protein level of autophagy marker proteins, like

Atg complex (Atg5, Atg7, Atg12, Atg14 and Atg16L1), beclin 1, PI3K

class III, rubicon and LC3, was also investigated in

ANK-199-treated CAR cells. As shown in Fig. 5, ANK-199 at 50 and 75 μM increased

the protein levels of Atg5, Atg7, Atg12, Atg14 and Atg16L1, beclin

1, PI3K class III and LC3, but decreased the protein level of

rubicon in CAR cells. Our results imply that ANK-199 induced

autophagic cell death in CAR cells through interfering with the

kinase class III/beclin 1/Atg-associated signal pathway.

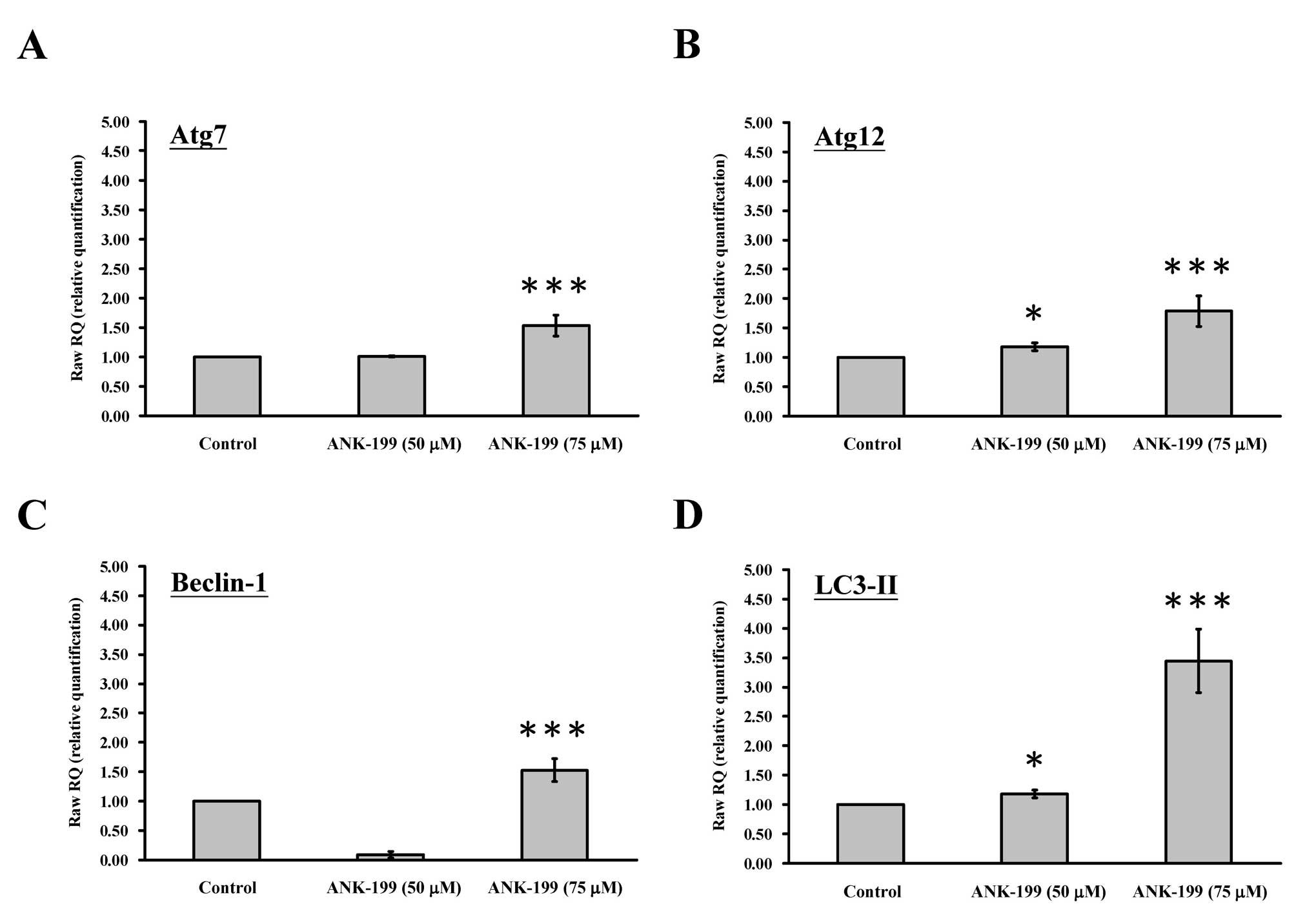

ANK-199 stimulates the

autophagy-associated mRNA levels in CAR cells

The mRNA level of autophagy-associated gene was also

investigated in ANK-199-treated CAR cells. As shown in Fig. 6, ANK-199 is able to enhance the

expression level of Atg7 gene (Fig. 6A), Atg12 gene (Fig. 6B), beclin 1 gene (Fig. 6C) and LC3-II gene (Fig. 6D) in CAR cells.

Protection effect of 3-MA against

autophagy in ANK-199- treated CAR cells

3-MA, an inhibitor of PI3K kinase class III, has

been shown to potently inhibit autophagy-dependent protein

degradation and suppress the formation of autophagosomes. CAR cells

were pretreated with 3-MA and then exposed to 50 or 75 μM of

ANK-199. The formation of autophagic vacuoles and cell viability

were then monitored under phase contrast microscopy. Our results

showed that 3-MA can inhibit the formation of autophagic vacuoles

(Fig. 7A) and enhance the

viability of ANK-199-treated CAR cells (Fig. 7B), suggesting that ANK-199-induced

autophagy in CAR cells is mediated through interference with the

PI3K kinase class III.

Microarray analysis

The cDNA microarray experiments were carried out to

examine the gene expression in ANK-199-treated CAR cells. The

transcripts of 26 genes were upregulated, while these of 96 genes

were downregulated in ANK-199-treated CAR cells (Table I). The important biological

processes and Gene to Go Molecular Function test regulated by

ANK-199 are listed in Table II

and Table III. The formation of

autophagosomes and autophagolysosome was observed during the course

of ANK-199 induced autophagic cell death. In a good agreement with

above results, membrane formation or reorganization is closely

associated with following biological processes: cellular component

biogenesis, actin cytoskeleton organization, regulation of actin

filament-based process, regulation of cytoskeleton organization,

regulation of actin polymerization or depolymerization, regulation

of actin filament length.

| Table IThe genes with more than 1.5-fold

changes in mRNA levels in CAR cells after ANK-199 (50 μM) 24-h

treatment identified by DNA microarray. |

Table I

The genes with more than 1.5-fold

changes in mRNA levels in CAR cells after ANK-199 (50 μM) 24-h

treatment identified by DNA microarray.

| Accession | Gene | FC |

|---|

| XR_042379 | LOC401875:

hypothetical LOC401875 | 7.34 |

| NM_198581 | ZC3H6: zinc finger

CCCH-type containing 6 | 5.68 |

| NM_004755 | RPS6KA5: ribosomal

protein S6 kinase, 90 kDa, polypeptide 5 | 3.27 |

| NM_006472 | TXNIP: thioredoxin

interacting protein | 3.00 |

| NM_001506 | GPR32: G

protein-coupled receptor 32 | 2.15 |

| NM_018387 | STRBP: spermatid

perinuclear RNA binding protein | 2.04 |

| BC007928 | C21orf119:

chromosome 21 open reading frame 119 | 1.93 |

| BC108718 | LOC389765: similar

to KIF27C | 1.88 |

| NM_153335 | LYK5: protein

kinase LYK5 | 1.86 |

|

ENST00000021776 | CCT8L1: chaperonin

containing TCP1, subunit 8 (theta)-like 1 | 1.81 |

| NM_018434 | RNF130: ring finger

protein 130 | 1.75 |

| NM_181684 | KRTAP12-2: keratin

associated protein 12-2 | 1.72 |

| NM_201266 | NRP2: neuropilin

2 | 1.71 |

| NM_181351 | NCAM1: neural cell

adhesion molecule 1 | 1.63 |

| NM_004064 | CDKN1B:

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1B (p27, Kip1) | 1.63 |

| NM_007051 | FAF1: Fas (TNFRSF6)

associated factor 1 | 1.62 |

| NM_001039752 | SLC22A10: solute

carrier family 22, member 10 | 1.62 |

| NM_198993 | STAC2: SH3 and

cysteine rich domain 2 | 1.62 |

| NM_018257 | PCMTD2:

protein-L-isoaspartate (D-aspartate) O-methyltransferase domain

containing 2 | 1.62 |

| NM_000901 | NR3C2: nuclear

receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 2 | 1.62 |

| BC093665 | FAM92B: family with

sequence similarity 92, member B | 1.56 |

| NM_016609 | SLC22A17: solute

carrier family 22, member 17 | 1.55 |

| NM_181605 | KRTAP6-3: keratin

associated protein 6-3 | 1.55 |

| XM_938903 | LOC649839: similar

to large subunit ribosomal protein L36a | 1.53 |

| BC021739 | LOC554201:

hypothetical LOC554201 | 1.53 |

|

ENST00000329244 | LOC100132169:

similar to hCG1742852 | 1.50 |

| NM_021109 | TMSB4X: thymosin

beta 4, X-linked | −1.50 |

| NM_019896 | POLE4: polymerase

(DNA-directed), epsilon 4 (p12 subunit) | −1.51 |

| NM_015475 | FAM98A: family with

sequence similarity 98, member A | −1.51 |

| NM_006136 | CAPZA2: capping

protein (actin filament) muscle Z-line, alpha 2 | −1.51 |

| NM_001128619 | LUZP6: leucine

zipper protein 6 | −1.51 |

| NM_014248 | RBX1: ring-box

1 | −1.52 |

| NM_024755 | SLTM: SAFB-like,

transcription modulator | −1.53 |

| NM_003168 | SUPT4H1: suppressor

of Ty 4 homolog 1 (S. cerevisiae) | −1.53 |

| NM_017892 | PRPF40A: PRP40

pre-mRNA processing factor 40 homolog A (S. cerevisiae) | −1.53 |

| NM_004776 | B4GALT5:

UDP-Gal:betaGlcNAc beta 1,4-galactosyltransferase, polypeptide

5 | −1.53 |

| NM_002090 | CXCL3: chemokine

(C-X-C motif) ligand 3 | −1.53 |

| NM_001005333 | MAGED1: melanoma

antigen family D, 1 | −1.53 |

| NM_000937 | POLR2A: polymerase

(RNA) II (DNA directed) polypeptide A, 220 kDa | −1.54 |

| NM_001349 | DARS: aspartyl-tRNA

synthetase | −1.55 |

| NM_003348 | UBE2N:

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2N (UBC13 homolog, yeast) | −1.56 |

| NM_001614 | ACTG1: actin, gamma

1 | −1.56 |

| NM_053024 | PFN2: profilin

2 | −1.56 |

| NM_003010 | MAP2K4:

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 | −1.57 |

| NM_001099771 | A26C1B:

ANKRD26-like family C, member 1B | −1.57 |

| NM_006000 | TUBA4A: tubulin,

alpha 4a | −1.58 |

| NM_133494 | NEK7: NIMA (never

in mitosis gene a)-related kinase 7 | −1.59 |

| NM_173647 | RNF149: ring finger

protein 149 | −1.59 |

| NM_182917 | EIF4G1: eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 4 gamma, 1 | −1.59 |

| NM_002599 | PDE2A:

phosphodiesterase 2A, cGMP-stimulated | −1.62 |

| NM_005066 | SFPQ: splicing

factor proline/glutamine-rich (polypyrimidine tract binding protein

associated) | −1.64 |

| NM_001039479 | KIAA0317:

KIAA0317 | −1.64 |

| NM_001127649 | PEX26: peroxisomal

biogenesis factor 26 | −1.64 |

| NM_015153 | PHF3: PHD finger

protein 3 | −1.64 |

| NM_007189 | ABCF2: ATP-binding

cassette, sub-family F (GCN20), member 2 | −1.64 |

| NM_007126 | VCP:

valosin-containing protein | −1.64 |

| NM_012234 | RYBP: RING1 and YY1

binding protein | −1.65 |

| NR_004845 | LOC644936:

cytoplasmic beta-actin pseudogene | −1.65 |

| NM_014795 | ZEB2: zinc finger

E-box binding homeobox 2 | −1.66 |

| NM_005998 | CCT3: chaperonin

containing TCP1, subunit 3 (gamma) | −1.67 |

| NM_001099692 | EIF5AL1: eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 5A-like 1 | −1.67 |

| NM_138689 | PPP1R14B: protein

phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 14B | −1.67 |

| NM_015665 | AAAS: achalasia,

adrenocortical insufficiency, alacrimia (Allgrove, triple-A) | −1.67 |

| NM_001099692 | EIF5AL1: eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 5A-like 1 | −1.68 |

| NM_001099692 | EIF5AL1: eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 5A-like 1 | −1.68 |

| NM_002154 | HSPA4: heat shock

70 kDa protein 4 | −1.68 |

| NM_013451 | FER1L3: fer-1-like

3, myoferlin (C. elegans) | −1.70 |

| NM_000303 | PMM2:

phosphomannomutase 2 | −1.71 |

| NM_002795 | PSMB3: proteasome

(prosome, macropain) subunit, beta type, 3 | −1.71 |

| NM_001363 | DKC1: dyskeratosis

congenita 1, dyskerin | −1.71 |

| NM_001102 | ACTN1: actinin,

alpha 1 | −1.73 |

| NM_004299 | ABCB7: ATP-binding

cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP), member 7 | −1.73 |

| NM_005857 | ZMPSTE24: zinc

metallopeptidase (STE24 homolog, S. cerevisiae) | −1.74 |

| NM_152265 | BTF3L4: basic

transcription factor 3-like 4 | −1.74 |

| NM_020409 | MRPL47:

mitochondrial ribosomal protein L47 | −1.74 |

| NM_006148 | LASP1: LIM and SH3

protein 1 | −1.76 |

| BC065192 | C2orf12: chromosome

2 open reading frame 12 | −1.76 |

| NM_001414 | EIF2B1: eukaryotic

translation initiation factor 2B, subunit 1 alpha, 26 kDa | −1.78 |

| NM_003222 | TFAP2C:

transcription factor AP-2 gamma (activating enhancer binding

protein 2 gamma) | −1.78 |

| NM_007350 | PHLDA1: pleckstrin

homology-like domain, family A, member 1 | −1.79 |

|

ENST00000242577 | DYNLL1: dynein,

light chain, LC8-type 1 | −1.79 |

| NM_032830 | CIRH1A: cirrhosis,

autosomal recessive 1A (cirhin) | −1.79 |

| NM_152265 | BTF3L4: basic

transcription factor 3-like 4 | −1.80 |

| NM_176816 | CCDC125:

coiled-coil domain containing 125 | −1.80 |

| NM_001039690 | CTF8: chromosome

transmission fidelity factor 8 homolog (S. cerevisiae) | −1.83 |

| NM_001127257 | SLC39A10: solute

carrier family 39 (zinc transporter), member 10 | −1.84 |

| XM_001716411 | LOC128322:

hypothetical LOC128322 | −1.86 |

| NM_002370 | MAGOH: mago-nashi

homolog, proliferation-associated (Drosophila) | −1.90 |

| NM_138578 | BCL2L1: BCL2-like

1 | −1.91 |

| NM_003580 | NSMAF: neutral

sphingomyelinase (N-SMase) activation associated factor | −1.92 |

| NM_015922 | NSDHL: NAD(P)

dependent steroid dehydrogenase-like | −1.92 |

| NM_001797 | CDH11: cadherin 11,

type 2, OB-cadherin (osteoblast) | −1.93 |

| NM_021242 | MID1IP1: MID1

interacting protein 1 [gastrulation specific G12 homolog

(zebrafish)] | −1.93 |

| NM_005968 | HNRNPM:

heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M | −1.95 |

| NM_012338 | TSPAN12:

tetraspanin 12 | −1.97 |

| NM_014953 | DIS3: DIS3 mitotic

control homolog (S. cerevisiae) | −2.02 |

| NM_003130 | SRI: sorcin | −2.11 |

| NM_018993 | RIN2: Ras and Rab

interactor 2 | −2.12 |

| NM_004093 | EFNB2:

ephrin-B2 | −2.13 |

| NM_032256 | TMEM117:

transmembrane protein 117 | −2.14 |

| NM_005415 | SLC20A1: solute

carrier family 20 (phosphate transporter), member 1 | −2.15 |

| NM_017872 | THG1L:

tRNA-histidine guanylyltransferase 1-like (S. cerevisiae) | −2.20 |

| NM_014624 | S100A6: S100

calcium binding protein A6 | −2.24 |

| NM_153618 | SEMA6D: sema

domain, transmembrane domain (TM), and cytoplasmic domain,

(semaphorin) 6D | −2.27 |

| NM_014604 | TAX1BP3: Tax1

(human T-cell leukemia virus type I) binding protein 3 | −2.27 |

| NM_033505 | SELI: selenoprotein

I | −2.30 |

| NM_003666 | BLZF1: basic

leucine zipper nuclear factor 1 | −2.35 |

| NM_002714 | PPP1R10: protein

phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 10 | −2.50 |

| NM_002714 | PPP1R10: protein

phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 10 | −2.50 |

| NM_002714 | PPP1R10: protein

phosphatase 1, regulatory (inhibitor) subunit 10 | −2.50 |

| NR_003003 | SCARNA17: small

Cajal body-specific RNA 17 | −2.51 |

| NR_002738 | SNORD57: small

nucleolar RNA, C/D box 57 | −2.57 |

| NM_006080 | SEMA3A: sema

domain, immunoglobulin domain (Ig), short basic domain, secreted,

(semaphorin) 3A | −2.57 |

| NM_009587 | LGALS9: lectin,

galactoside-binding, soluble, 9 | −2.65 |

| NM_003234 | TFRC: transferrin

receptor (p90, CD71) | −2.85 |

| NM_138966 | NETO1: neuropilin

(NRP) and tolloid (TLL)-like 1 | −2.97 |

| NM_001098272 | HMGCS1:

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A synthase 1 (soluble) | −2.97 |

| NM_006350 | FST:

follistatin | −4.21 |

| NM_024090 | ELOVL6: ELOVL

family member 6, elongation of long chain fatty acids(FEN1/Elo2,

SUR4/Elo3-like, yeast) | −4.46 |

| NM_005328 | HAS2: hyaluronan

synthase 2 | −5.00 |

| NM_001753 | CAV1: caveolin 1,

caveolae protein, 22 kDa | −5.04 |

| NM_033439 | IL33: interleukin

33 | −5.96 |

| Table IIGene to GO Biological Process test

for over-representation (ANK-199 to control). |

Table II

Gene to GO Biological Process test

for over-representation (ANK-199 to control).

| Term | Count | % | p-value |

|---|

| GO:0044087 -

regulation of cellular component biogenesis | 9 | 6.382979 | 8.59E-06 |

| GO:0030036 - actin

cytoskeleton organization | 10 | 7.092199 | 3.75E-05 |

| GO:0032956 -

regulation of actin cytoskeleton organization | 7 | 4.964539 | 4.43E-05 |

| GO:0043254 -

regulation of protein complex assembly | 7 | 4.964539 | 4.72E-05 |

| GO:0032970 -

regulation of actin filament-based process | 7 | 4.964539 | 5.34E-05 |

| GO:0051493 -

regulation of cytoskeleton organization | 8 | 5.673759 | 5.75E-05 |

| GO:0030029 - actin

filament-based process | 10 | 7.092199 | 6.17E-05 |

| GO:0007010 -

cytoskeleton organization | 13 | 9.219858 | 7.13E-05 |

| GO:0008064 -

regulation of actin polymerization or depolymerization | 6 | 4.255319 | 7.77E-05 |

| GO:0030832 -

regulation of actin filament length | 6 | 4.255319 | 9.07E-05 |

| Table IIIGene to GO Molecular Function test

for over-representation (ANK-199 to control). |

Table III

Gene to GO Molecular Function test

for over-representation (ANK-199 to control).

| Term | Count | % | p-value |

|---|

| GO:0003723 - RNA

binding | 21 | 14.89362 | 1.54E-07 |

| GO:0000166 -

nucleotide binding | 33 | 23.40426 | 6.28E-05 |

| GO:0008092 -

cytoskeletal protein binding | 11 | 7.801418 | 0.00346 |

| GO:0032553 -

ribonucleotide binding | 24 | 17.02128 | 0.005183 |

| GO:0032555 - purine

ribonucleotide binding | 24 | 17.02128 | 0.005183 |

| GO:0017076 - purine

nucleotide binding | 24 | 17.02128 | 0.008794 |

| GO:0003779 - actin

binding | 8 | 5.673759 | 0.009366 |

| GO:0019900 - kinase

binding | 6 | 4.255319 | 0.009636 |

| GO:0047485 -

protein N-terminus binding | 4 | 2.836879 | 0.016454 |

| GO:0003924 - GTPase

activity | 6 | 4.255319 | 0.018492 |

Discussion

Apoptosis, autophagy and necrosis are three major

routes that lead to cell death (51). Both apoptosis and autophagy belong

to the form of cell programmed death, but necrosis does not

(51–54). Autophagic death can promote cell

survival or cell death when cells experience stress, such as

damage, nutrient starvation, aging and pathogen infection (55–57).

Indeed, induction of autophagic death for cancer cells is thought

to be one of the best strategies in chemotherapy (58–60).

Not only many autophagy-related proteins (Atgs) are involved in

this process, but also a specific morphological and biochemical

modification can be observed (56,60,61).

Autophagy is first triggered by membrane nucleation, which is

mediated by phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) class III, beclin

1 (the mammalian ortholog of yeast ATG6), rubicon and Atg14

(62–64). The cytoplasm and phagophore of

various organelles are then sequestered by a membrane to form an

autophagosomes. Atg16L1-Atg12-Atg7-Atg5 complex and

microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 type II (LC3-II)

(membrane-bound form) are absolutely required for autophagosome

formation (55,65–67).

The autophagosome fuses with the lysosome then forming

autophagolysosome, eventually resulting in the degradation of the

captured proteins or organelles by lysosomal enzymes (55,68,69).

Once cells undergo autophagic cell death, an autophagosomal marker

LC3-II increases from the conversion of LC3-I (70,71).

Our results demonstrated that the ANK-199 can induce

the formation of autophagic vesicle (Fig. 4A) and acidic vesicular organelles

(Fig. 4B). It also simultaneously

enhances the protein level of autophagic proteins, Atg complex,

beclin 1, PI3K class III and LC3-II (Fig. 5), and mRNA expression of autophagic

genes Atg7, Atg12, beclin 1 and LC3-II

(Fig. 6). More importantly, 3-MA,

a specific inhibitor of PI3K kinase class III, can inhibit the

autophagic vesicle formation induced by ANK-199 (Fig. 7). All of the above results support

that ANK-199-induced cell death in CAR cells is mediated through

the induction of autophagic death. This molecular signaling pathway

induced by ANK-199 is summarized in Fig. 8.

However, ANK-199 treatment duration for CAR cells is

72 h. We cannot completely rule out the possibility that apoptotic

cell death or other signaling pathways can be induced by ANK-199

for longer treatment time. A series of pterostilbene derivatives

have been synthesized as less toxic anticancer candidates (30,40,72,73).

ANK-199 is less toxic than pterostilbene (unpublished data). More

importantly, ANK-199 has much less cytotoxicity in the normal oral

cells (HGF and OK) than that in CAR cells (Fig. 3). This is a novel finding regarding

that ANK-199 represents a promising candidate as an anti-oral

cancer drug with low toxicity to normal cells. Results presented in

this study show that ANK-199 may become a novel therapeutic reagent

for the treatment of oral cancer in the near future (patent

pending).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by AnnCare Bio-Tech Center

Inc. and a research grant from the Ministry of Health and Welfare,

Executive Yuan, Taiwan (DOH101-TD-C-111-005) awarded to S.-C.K.

References

|

1

|

Estrela JM, Ortega A, Mena S, Rodriguez ML

and Asensi M: Pterostilbene: Biomedical applications. Crit Rev Clin

Lab Sci. 50:65–78. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

McCormack D and McFadden D: A review of

pterostilbene antioxidant activity and disease modification. Oxid

Med Cell Longev. 2013:5754822013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cherniack EP: A berry thought-provoking

idea: the potential role of plant polyphenols in the treatment of

age-related cognitive disorders. Br J Nutr. 108:794–800. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

McCormack D and McFadden D: Pterostilbene

and cancer: current review. J Surg Res. 173:e53–e61. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Mikstacka R and Ignatowicz E:

Chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic effect of trans-resveratrol

and its analogues in cancer. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 28:496–500.

2010.(In Polish).

|

|

6

|

Rimando AM and Suh N:

Biological/chemopreventive activity of stilbenes and their effect

on colon cancer. Planta Med. 74:1635–1643. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li N, Ma Z, Li M, Xing Y and Hou Y:

Natural potential therapeutic agents of neurodegenerative diseases

from the traditional herbal medicine Chinese Dragons Blood. J

Ethnopharmacol. 152:508–521. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Paul S, Rimando AM, Lee HJ, Ji Y, Reddy BS

and Suh N: Anti-inflammatory action of pterostilbene is mediated

through the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in colon

cancer cells. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2:650–657. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pan MH, Chang YH, Tsai ML, et al:

Pterostilbene suppressed lipopolysaccharide-induced up-expression

of iNOS and COX-2 in murine macrophages. J Agric Food Chem.

56:7502–7509. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Perecko T, Drabikova K, Rackova L, et al:

Molecular targets of the natural antioxidant pterostilbene: effect

on protein kinase C, caspase-3 and apoptosis in human neutrophils

in vitro. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 31(Suppl 2): 84–90.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Perecko T, Jancinova V, Drabikova K, Nosal

R and Harmatha J: Structure-efficiency relationship in derivatives

of stilbene. Comparison of resveratrol, pinosylvin and

pterostilbene. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 29:802–805. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rossi M, Caruso F, Antonioletti R, et al:

Scavenging of hydroxyl radical by resveratrol and related natural

stilbenes after hydrogen peroxide attack on DNA. Chem Biol

Interact. 206:175–185. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Acharya JD and Ghaskadbi SS: Protective

effect of pterostilbene against free radical mediated oxidative

damage. BMC Complement Altern Med. 13:2382013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rimando AM, Cuendet M, Desmarchelier C,

Mehta RG, Pezzuto JM and Duke SO: Cancer chemopreventive and

antioxidant activities of pterostilbene, a naturally occurring

analogue of resveratrol. J Agric Food Chem. 50:3453–3457. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pan MH, Chang YH, Badmaev V, Nagabhushanam

K and Ho CT: Pterostilbene induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest

in human gastric carcinoma cells. J Agric Food Chem. 55:7777–7785.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ferrer P, Asensi M, Priego S, et al:

Nitric oxide mediates natural polyphenol-induced Bcl-2

down-regulation and activation of cell death in metastatic B16

melanoma. J Biol Chem. 282:2880–2890. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Siedlecka-Kroplewska K, Jozwik A,

Boguslawski W, et al: Pterostilbene induces accumulation of

autophagic vacuoles followed by cell death in HL60 human leukemia

cells. J Physiol Pharmacol. 64:545–556. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hsieh MJ, Lin CW, Yang SF, et al: A

combination of pterostilbene with autophagy inhibitors exerts

efficient apoptotic characteristics in both chemosensitive and

chemoresistant lung cancer cells. Toxicol Sci. 137:65–75. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kapoor S: Pterostilbene and its emerging

antineoplastic effects: a prospective treatment option for systemic

malignancies. Am J Surg. 205:4832013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tippani R, Prakhya LJ, Porika M, Sirisha

K, Abbagani S and Thammidala C: Pterostilbene as a potential novel

telomerase inhibitor: Molecular docking studies and its in vitro

evaluation. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. Jan 12–2014.(Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

21

|

Li K, Dias SJ, Rimando AM, et al:

Pterostilbene acts through metastasis-associated protein 1 to

inhibit tumor growth, progression and metastasis in prostate

cancer. PLoS One. 8:e575422013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

McCormack DE, Mannal P, McDonald D, Tighe

S, Hanson J and McFadden D: Genomic analysis of pterostilbene

predicts its antiproliferative effects against pancreatic cancer in

vitro and in vivo. J Gastrointest Surg. 16:1136–1143. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Mannal PW, Alosi JA, Schneider JG,

McDonald DE and McFadden DW: Pterostilbene inhibits pancreatic

cancer in vitro. J Gastrointest Surg. 14:873–879. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Moon D, McCormack D, McDonald D and

McFadden D: Pterostilbene induces mitochondrially derived apoptosis

in breast cancer cells in vitro. J Surg Res. 180:208–215. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Pan MH, Lin YT, Lin CL, Wei CS, Ho CT and

Chen WJ: Suppression of heregulin-beta1/HER2-modulated invasive and

aggressive phenotype of breast carcinoma by pterostilbene via

inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9, p38 kinase cascade and

Akt activation. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med.

2011:5621872011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yang Y, Yan X, Duan W, et al:

Pterostilbene exerts antitumor activity via the Notch1 signaling

pathway in human lung adenocarcinoma cells. PLoS One. 8:e626522013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Liu Y, Wang L, Wu Y, et al: Pterostilbene

exerts antitumor activity against human osteosarcoma cells by

inhibiting the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathway. Toxicology.

304:120–131. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lin VC, Tsai YC, Lin JN, et al: Activation

of AMPK by pterostilbene suppresses lipogenesis and cell-cycle

progression in p53 positive and negative human prostate cancer

cells. J Agric Food Chem. 60:6399–6407. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Chakraborty A, Gupta N, Ghosh K and Roy P:

In vitro evaluation of the cytotoxic, anti-proliferative and

anti-oxidant properties of pterostilbene isolated from

Pterocarpus marsupium. Toxicol In Vitro. 24:1215–1228. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Roslie H, Chan KM, Rajab NF, et al:

3,5-Dibenzyloxy-4′-hydroxystilbene induces early caspase-9

activation during apoptosis in human K562 chronic myelogenous

leukemia cells. J Toxicol Sci. 37:13–21. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Tolomeo M, Grimaudo S, Di Cristina A, et

al: Pterostilbene and 3′-hydroxypterostilbene are effective

apoptosis-inducing agents in MDR and BCR-ABL-expressing leukemia

cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 37:1709–1726. 2005.

|

|

32

|

Mena S, Rodriguez ML, Ponsoda X, Estrela

JM, Jaattela M and Ortega AL: Pterostilbene-induced tumor

cytotoxicity: a lysosomal membrane permeabilization-dependent

mechanism. PLoS One. 7:e445242012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Harun Z and Ghazali AR: Potential

chemoprevention activity of pterostilbene by enhancing the

detoxifying enzymes in the HT-29 cell line. Asian Pac J Cancer

Prev. 13:6403–6407. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Nutakul W, Sobers HS, Qiu P, et al:

Inhibitory effects of resveratrol and pterostilbene on human colon

cancer cells: a side-by-side comparison. J Agric Food Chem.

59:10964–10970. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Huang CS, Ho CT, Tu SH, et al: Long-term

ethanol exposure-induced hepatocellular carcinoma cell migration

and invasion through lysyl oxidase activation are attenuated by

combined treatment with pterostilbene and curcumin analogues. J

Agric Food Chem. 61:4326–4335. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Pan MH, Chiou YS, Chen WJ, Wang JM,

Badmaev V and Ho CT: Pterostilbene inhibited tumor invasion via

suppressing multiple signal transduction pathways in human

hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 30:1234–1242. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Siedlecka-Kroplewska K, Jozwik A,

Kaszubowska L, Kowalczyk A and Boguslawski W: Pterostilbene induces

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MOLT4 human leukemia cells.

Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 50:574–580. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Chen RJ, Tsai SJ, Ho CT, et al:

Chemopreventive effects of pterostilbene on urethane-induced lung

carcinogenesis in mice via the inhibition of EGFR-mediated pathways

and the induction of apoptosis and autophagy. J Agric Food Chem.

60:11533–11541. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Chakraborty A, Bodipati N, Demonacos MK,

Peddinti R, Ghosh K and Roy P: Long term induction by pterostilbene

results in autophagy and cellular differentiation in MCF-7 cells

via ROS dependent pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 355:25–40. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chen RJ, Ho CT and Wang YJ: Pterostilbene

induces autophagy and apoptosis in sensitive and chemoresistant

human bladder cancer cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 54:1819–1832. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Zhang L, Cui L, Zhou G, Jing H, Guo Y and

Sun W: Pterostilbene, a natural small-molecular compound, promotes

cytoprotective macroautophagy in vascular endothelial cells. J Nutr

Biochem. 24:903–911. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Riche DM, McEwen CL, Riche KD, et al:

Analysis of safety from a human clinical trial with pterostilbene.

J Toxicol. 2013:4635952013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Shetty SR, Babu S, Kumari S, Prasad R,

Bhat S and Fazil KA: Salivary ascorbic acid levels in betel quid

chewers: A biochemical study. South Asian J Cancer. 2:142–144.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Arjungi KN: Areca nut: a review.

Arzneimittelforschung. 26:951–956. 1976.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Chang PY, Peng SF, Lee CY, et al:

Curcumin-loaded nanoparticles induce apoptotic cell death through

regulation of the function of MDR1 and reactive oxygen species in

cisplatin-resistant CAR human oral cancer cells. Int J Oncol.

43:1141–1150. 2013.

|

|

46

|

Lin C, Tsai SC, Tseng MT, et al: AKT

serine/threonine protein kinase modulates baicalin-triggered

autophagy in human bladder cancer T24 cells. Int J Oncol.

42:993–1000. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Tsai SC, Yang JS, Peng SF, et al: Bufalin

increases sensitivity to AKT/mTOR-induced autophagic cell death in

SK-HEP-1 human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol.

41:1431–1442. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Huang WW, Tsai SC, Peng SF, et al:

Kaempferol induces autophagy through AMPK and AKT signaling

molecules and causes G2/M arrest via downregulation of CDK1/cyclin

B in SK-HEP-1 human hepatic cancer cells. Int J Oncol.

42:2069–2077. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Huang AC, Lien JC, Lin MW, et al:

Tetrandrine induces cell death in SAS human oral cancer cells

through caspase activation-dependent apoptosis and LC3-I and LC3-II

activation-dependent autophagy. Int J Oncol. 43:485–494. 2013.

|

|

50

|

Liu CY, Yang JS, Huang SM, et al: Smh-3

induces G(2)/M arrest and apoptosis through calcium-mediated

endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial signaling in human

hepatocellular carcinoma Hep3B cells. Oncol Rep. 29:751–762.

2013.

|

|

51

|

Jin Z and El-Deiry WS: Overview of cell

death signaling pathways. Cancer Biol Ther. 4:139–163.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jin S and White E: Role of autophagy in

cancer: management of metabolic stress. Autophagy. 3:28–31. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Fink SL and Cookson BT: Apoptosis,

pyroptosis, and necrosis: mechanistic description of dead and dying

eukaryotic cells. Infect Immun. 73:1907–1916. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Lockshin RA and Zakeri Z: Apoptosis,

autophagy, and more. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 36:2405–2419. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Shimizu S, Yoshida T, Tsujioka M and

Arakawa S: Autophagic cell death and cancer. Int J Mol Sci.

15:3145–3153. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Mukhopadhyay S, Panda PK, Sinha N, Das DN

and Bhutia SK: Autophagy and apoptosis: where do they meet?

Apoptosis. 19:555–566. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Ma Y, Galluzzi L, Zitvogel L and Kroemer

G: Autophagy and cellular immune responses. Immunity. 39:211–227.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Morselli E, Galluzzi L, Kepp O, et al:

Anti- and pro-tumor functions of autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1793:1524–1532. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Li LC, Liu GD, Zhang XJ and Li YB:

Autophagy, a novel target for chemotherapeutic intervention of

thyroid cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 73:439–449. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Meschini S, Condello M, Lista P and

Arancia G: Autophagy: Molecular mechanisms and their implications

for anticancer therapies. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 11:357–379.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Liu B, Bao JK, Yang JM and Cheng Y:

Targeting autophagic pathways for cancer drug discovery. Chin J

Cancer. 32:113–120. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Ghavami S, Shojaei S, Yeganeh B, et al:

Autophagy and apoptosis dysfunction in neurodegenerative disorders.

Prog Neurobiol. 112:24–49. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Fu LL, Cheng Y and Liu B: Beclin-1:

autophagic regulator and therapeutic target in cancer. Int J

Biochem Cell Biol. 45:921–924. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kang R, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT and Tang D: The

Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death

Differ. 18:571–580. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Parkes M: Evidence from genetics for a

role of autophagy and innate immunity in IBD pathogenesis. Dig Dis.

30:330–333. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Martinez-Lopez N and Singh R: ATGs:

Scaffolds for MAPK/ERK signaling. Autophagy. 10:535–537. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Tam BT and Siu PM: Autophagic cellular

responses to physical exercise in skeletal muscle. Sports Med.

44:625–640. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Jiang P and Mizushima N: Autophagy and

human diseases. Cell Res. 24:69–79. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Pottier M, Masclaux-Daubresse C, Yoshimoto

K and Thomine S: Autophagy as a possible mechanism for

micronutrient remobilization from leaves to seeds. Front Plant Sci.

5:112014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Schmeisser H, Bekisz J and Zoon KC: New

function of type I IFN: Induction of autophagy. J Interferon

Cytokine Res. 34:71–78. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Mizushima N and Yoshimori T: How to

interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy. 3:542–545. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Zhang W, Sviripa V, Kril LM, et al:

Fluorinated N,N-dialkylaminostilbenes for Wnt pathway inhibition

and colon cancer repression. J Med Chem. 54:1288–1297. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Fuendjiep V, Wandji J, Tillequin F, et al:

Chalconoid and stilbenoid glycosides from Guibourtia

tessmanii. Phytochemistry. 60:803–806. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|