Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of gynecologic

cancer deaths in the United States (US) (1). While ovarian cancer has a typically

good response to first-line combination chemotherapy after initial

cytoreductive surgery, the prognosis of patients with advanced

malignant ovarian cancer remains poor because of acquired

chemotherapy resistance (2).

Despite recent advances made in chemotherapies of ovarian cancer,

the overall survival of patients has not improved significantly

because a considerable number of patients harbor ovarian cancer

refractory to these therapies and the majority of the initially

responsive tumors become resistant to treatments (3). Thus, the development of novel

targeted therapy that retains activity against

chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer is an unmet and urgent

medical need.

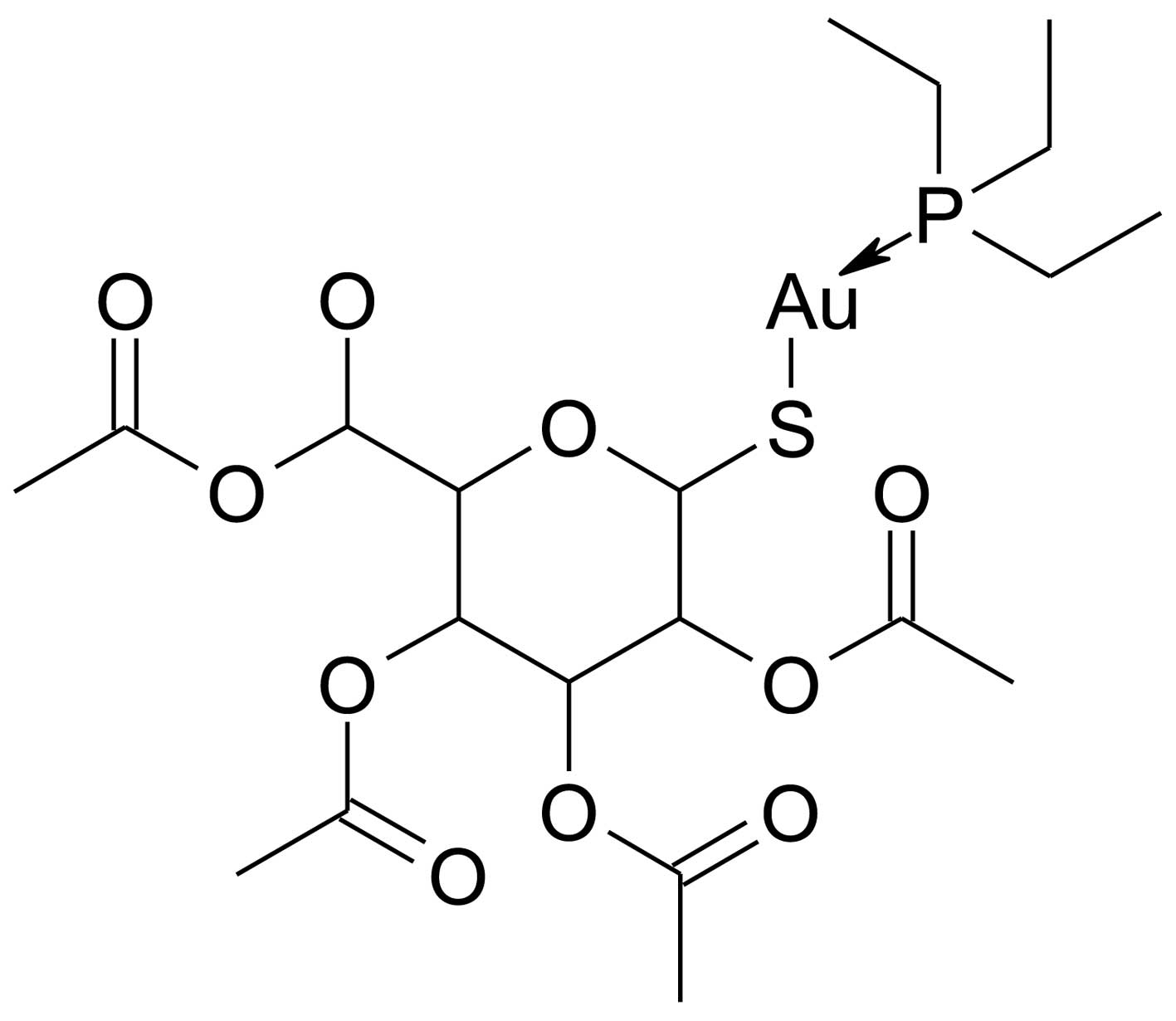

Auranofin

[2,3,4,6-tetra-o-acetyl-1-thio-β-D-glucopyranosato-S-(triethyl-phosphine)

gold] is a thiol-reactive gold (I)-containing compound (Fig. 1) that reduces the effects of the

inflammatory process in the body, and has been utilized to treat

rheumatoid arthritis by reducing pain and swelling (4,5).

Auranofin can inhibit IgE- and non-IgE-mediated histamine release

from human basophils and suppress the de novo synthesis of

sulfidopeptide leukotriene C4 (LTC4), which is induced by anti-IgE

from basophils and mast cells (6).

In addition, auranofin is a potent inhibitor of mitochondrial

thioredoxin reductase in vitro and in vivo, since

auranofin is able to block its active site (7). In addition, auranofin has been shown

to inhibit the activation of the IKK/NF-κB signaling pathway and

thereby downregulate the gene expression of pro-inflammatory

cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α (8–10).

Our previous study shows that IKK-β activation phosphorylates the

serine-644 residue in the FOXO3 protein and subsequently triggers

faster protein degradation of FOXO3 via the proteasome-mediated

ubiquitination (Ub) mechanism, which results in the stimulation of

human breast cancer cell proliferation in vitro and the

development of breast tumor in vivo (11,12).

These findings suggest that IKK-β may be a potential target for

anticancer therapy through FOXO3 activation. Interestingly, when we

screened for small molecules that can promote the activation of

FOXO3 in ovarian cancer cells, we identified auranofin as a

candidate FOXO3-activating small molecule from the US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA)-approved compound libraries. Since auranofin

is also a candidate inhibitor targeting IKK-β, it is a promising

small molecule candidate for development as anticancer

therapeutics.

FOXO3 is a member of the human Forkhead-box (FOX)

gene family that is known to have the distinct Forkhead DNA binding

domain (13). As a transcriptional

factor, FOXO3 is known to regulate various cellular processes such

as cell cycle (14,15), cellular apoptosis (16–19),

DNA damage repair (20,21), stress responses (15,22,23),

metabolism (24), aging (25) and tumor suppression in mammalian

cells (12,18,26).

The results from gene knockout exhibit key functions of FOXO family

members in tumor suppression (27)

and in preventing the decline of the hematopoietic stem cell pool

(28). The FOXO3 protein in cancer

cells can be regulated by various protein modification mechanisms

such as phosphorylation, acetylation and ubiquitination (25,29–31).

It has been shown that several active protein kinases (such as Akt,

IKK-β and MAPK) display the ability to phosphorylate the specific

serine/threonine residues on the FOXO3 protein and induce the

translocation of FOXO3 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. This

nuclear exclusion and translocation of FOXO3 into the cytoplasm

inhibits FOXO3-dependent transcription and results in the

proteasome-mediated Ub and protein degradation of FOXO3 (11,12,18,25,31).

This inhibition of function of FOXO3 leads to tumor development and

progression, suggesting that FOXO3 is a crucial tumor suppressor.

Importantly, several clinical studies on the relationship between

the FOXO3 protein nuclear localization or expression level and

cancer patient survival rates have revealed that FOXO3 is a good

prognostic biomarker for cancer survival (12,32–34),

which suggests that the regulation of FOXO3 activation in cancer

cells may be a promising strategy for developing anticancer

therapeutic drugs.

Sequential activation of caspases (the cysteinyl

aspartate-specific proteases) plays an important role in the

execution phase of cellular apoptosis (35). In general, caspases exist as

inactive pro-enzymes that undergo proteolytic processing at the

conserved aspartic residues to produce two fragments that form a

functional dimer as an active protease. It has been shown that

cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) by caspase-3, a

crucial protease in regulating apoptosis, at the pro-apoptotic

cleavage site of PARP1 produces the p85-kDa proteolytic fragment,

which has been suggested as a biomarker associated with apoptosis

(36,37).

In the present study, we used human ovarian

carcinoma SKOV3 cells, which are p53-null, as the cell model system

to investigate the cytotoxic activity and the anticancer mechanisms

of auranofin. Cell-based assays and biochemical analyses were

employed to elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying the

anticancer activity of auranofin in SKOV3 cells. Based on our

findings, we propose that FOXO family members may upregulate the

pro-apoptotic genes and downregulate certain cell survival genes

that contribute to the cellular apoptosis response to auranofin in

a p53-independent manner. The important biological and pathological

significance of this new mechanism of auranofin in cancer therapy

is discussed below.

Materials and methods

Chemical reagents and antibodies

Auranofin, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), glycerol,

glycine, sodium chloride, thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide,

Trizma base and Tween-20 were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO,

USA). Mouse anti-IκB kinase β (1:2,000 dilution), mouse anti-IκBα

(1:1,000 dilution), rabbit anti-p-IκBα (1:1,000 dilution), mouse

anti-PARP1 (1:1,000 dilution) and rabbit anti-FOXO3 (1:1,000

dilution) antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology

(Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:1,000

dilution), rabbit anti-Bax (1:1,000 dilution), rabbit anti-Bim

(1:1,000 dilution) and rabbit anti-Bcl-2 (1:1,000 dilution)

antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers,

MA, USA). Mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:3,000 dilution) was

purchased from Sigma. Goat anti-mouse and goat anti-rabbit

horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG were obtained from Jackson

ImmunoResearch (West Grove, PA, USA). ECL Western Blotting

Detection reagents were obtained from Genedepot (Barker, TX,

USA).

Cells, cell culture and siRNA

transfection

Human ovarian carcinoma SKOV3 cells (from ATCC) were

maintained in DMEM/F12 media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine

serum, 3% L-glutamine and 1% streptomycin/penicillin at 37°C in a

humidified incubator containing 5% CO2 in air.

FOXO3-siRNA and control-siRNA were obtained from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology. Cells were transfected with FOXO3-siRNA or

control-siRNA by using DharmaFECT 1 transfection reagent (Thermo

Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), according to the manufacturer’s

instructions and as described previously (19).

MTT cell viability assay

A 200 μl aliquot of cells (1×103 cells in

media) was added to each well of a 96-well plate and incubated for

18 h at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5% CO2

in air. After incubation, each dose (0, 50, 100, 200 and 400 nM) of

auranofin was added into the wells for 72 h for the dose-dependent

response assay and 100 nM of auranofin was added into the wells for

0, 24, 72 and 120 h for the time-dependent response assay. Control

cultures were treated with DMSO. After incubation, a 20 μl MTT

solution (5 mg/ml in phosphate buffer) was added to each well and

the incubation continued for 4 h, after which time the solution was

carefully removed. The blue crystalline precipitate was dissolved

in DMSO 200 μl. The visible absorbance at 560 nm of each well was

quantified using a microplate reader.

Cell counting assay

SKOV3 cells (1×104) were seeded in 6-cm

dishes and incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing

5% CO2 in air incubator for 18 h. After incubation,

cells were treated with DMSO as control vehicle and the indicated

concentration of auranofin (100 nM) for 0, 24, 72 and 120 h. Each

day, cell numbers were measured by using a hemocytometer.

Colony formation assay

SKOV3 cells (0.5×103) were seeded in 6-cm

dishes and incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing

5% CO2 in air incubator for 18 h. After incubation,

cells were treated with DMSO as control vehicle and the indicated

concentration of auranofin (100 nM) for 7 days. The colonies were

washed twice with PBS, fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde and stained

with 1% crystal violet solution in distilled water.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described

previously (11,12,19).

Briefly, cells were washed with PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (50

mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, pH

8.0) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cell lysates were

centrifuged (10,000 × g, 4°C, 10 min) and the supernatants were

separated on 6 or 10% SDS-PAGE gels and blotted onto nitrocellulose

membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). The membranes

were blocked in 3% non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature and

probed with appropriate antibodies. Membranes were then probed with

HRP-tagged anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibodies diluted

1:5,000–1:15,000 in 3% non-fat dry milk for 1 h at room

temperature. Chemiluminescence was detected using enhanced ECL.

Cytoplasmic and nuclear protein

fractionation

Cells from each condition were trypsinized,

centrifuged, washed, re-suspended in a cytoplasmic fractional

buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 500 mM sucrose, 1 mM EDTA,

0.5 mM spermidine, 0.15 mM spermine, 0.2% Triton X-100, 1 mM DTT, 2

μM PMSF and 0.15 U/ml aprotinin) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min on

a rotator. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 30

min at 4°C and the supernatant was collected for cytoplasmic

fraction. The nuclear pellet was washed twice with the washing

buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl, 25% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA,

0.5 mM spermidine and 0.15 mM spermine). The remaining pellet was

re-suspended with a nuclear fractional buffer (10 mM HEPES pH 8,

350 mM NaCl, 25% glycerol, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM spermidine and 0.15

mM spermine) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min on a rotator. The

nuclear suspension was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C,

the supernatant was collected for nuclear fraction. Protein in each

fraction was quantified by the Bradford protein determination

reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories), using BSA as a standard.

DNA fragmentation assay

SKOV3 cells (2×107 per sample) were

trypsinized, lysed in the lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA,

0.1% Triton-X 100, 0.1% SDS and pH 7.5) and incubated on ice for 30

min. The lysates were digested with RNase I followed by digestion

with proteinase K. The DNA was extracted by phenol-chloroform (1:1,

v/v), precipitated with 2 volumes of EtOH plus 10% NaAc (3 M, pH

5.2) and then dissolved in distilled water. Equal amounts of the

extracted DNA (2 μg/lane) and size markers (1-kb ladder) were

subjected to electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels, which were stained

with ethidium bromide and photographed.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as arithmetic mean ± SEM (the

standard error of the mean). To compare the statistical meaning

between the groups, two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test was used.

All experiments were repeated three times and the representative

data are shown. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

software (version 19.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Mean

differences with P-values <0.05 were considered statistically

significant.

Results

Auranofin inhibits cell survival or

growth of SKOV3 cells

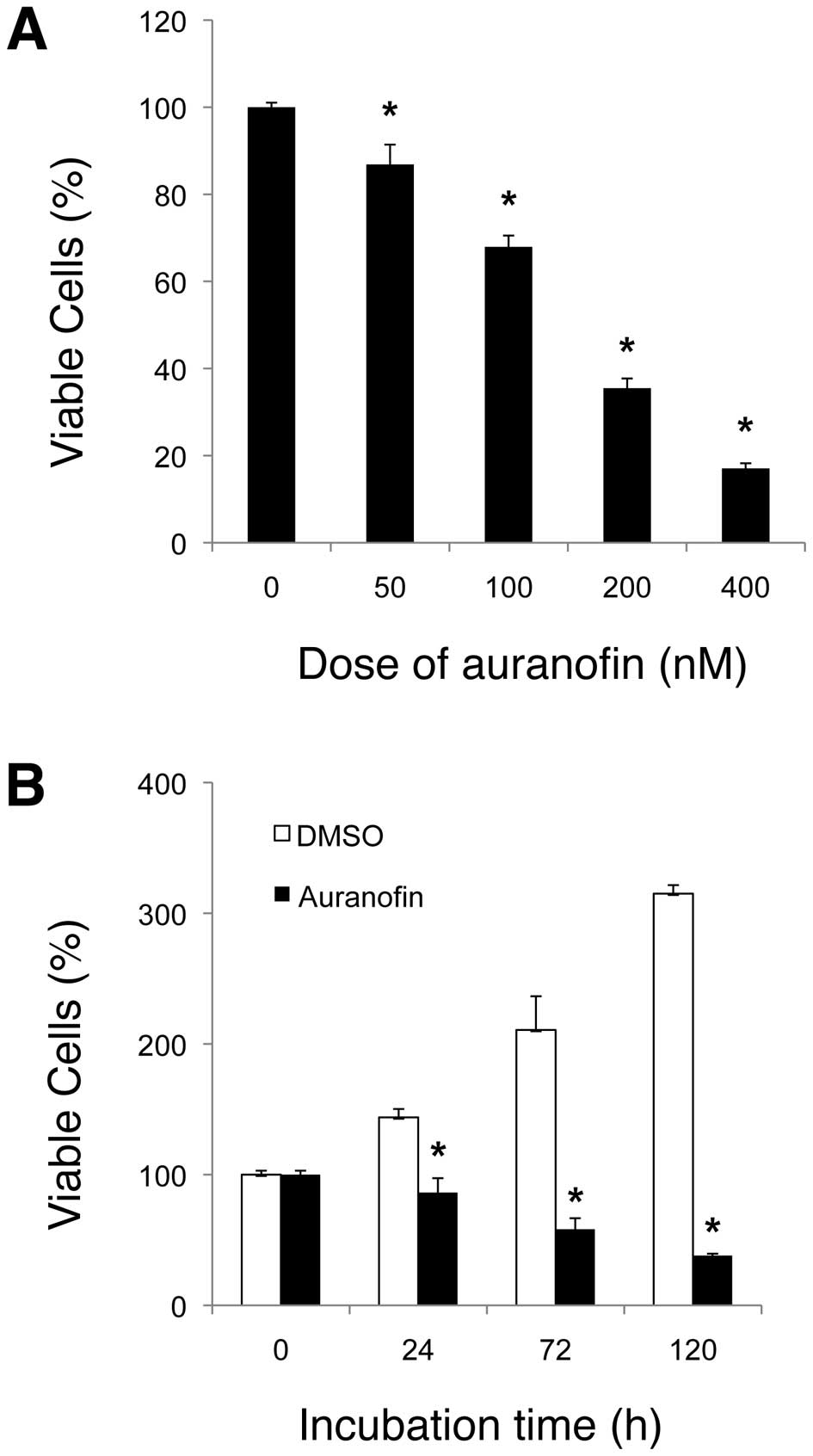

To examine the potential anticancer activity of

auranofin against ovarian cancer cells, we treated human ovarian

carcinoma SKOV3 cells with auranofin and measured the survival

and/or growth rate of SKOV3 cells using the MTT, cell counting and

colony formation assays. We showed that auranofin had an inhibitory

effect on SKOV3 cell survival/growth in a dose- and time-dependent

manner. After 72 h incubation, the dose-dependent assay data

indicated that the IC50 value of auranofin on SKOV3 was

~150 nM (Fig. 2A), which is

thought to be relatively low. The time-dependent assay results also

demonstrated the anti-survival/ proliferation activity of auranofin

(Fig. 2B), which was confirmed by

cell counting assay using the same treatment condition of auranofin

against SKOV3 cells (Fig. 3).

After 120 h incubation, the cell number in SKOV3 cells treated with

auranofin (100 nM) was significantly lower (~13 times) than that of

the control (DMSO) treatment. Furthermore, the clonogenic assay

results showed that auranofin treatment significantly suppressed

the colony-forming ability of SKOV3 cells (Fig. 4). Taken together, these results

support that auranofin displays a potent inhibitory effect on cell

survival/proliferation of ovarian carcinoma SKOV3 cells.

Auranofin induces cellular apoptosis in

SKOV3 cells

To examine the effect of auranofin on apoptosis in

SKOV3 cells, we performed western blot analyses and DNA

fragmentation assays. We found that the auranofin treatment (100 nM

for 48 h) increased the cleavage of PARP1 and caspase-3. Auranofin

also upregulated the expression of Bax and Bcl-2 interacting

mediator of cell death (Bim) in SKOV3 cells as compared with the

DMSO control treatment, whereas the auranofin treatment decreased

the Bcl-2 expression level under the same condition (Fig. 5A). These results suggest that

auranofin may exhibit its apoptotic effect through the

caspase-3-mediated mechanism in SKOV3 cells, the upregulation of

the mitochondrial proapoptotic Bax and Bim proteins and the

downregulation of the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 protein expression. Also,

when compared with the DMSO control, treatment of SKOV3 cells with

auranofin (100 nM) for 48 h resulted in an increase in the amount

of DNA fragmentation, a typical marker of apoptosis caused by the

cleaved (active) caspase-3 (Fig.

5B). Collectively, our results show that auranofin treatment

can induce cellular apoptosis in SKOV3 cells.

Auranofin downregulates the expression of

IKK-β and induces the nuclear translocation of FOXO3 protein in

SKOV3 cells

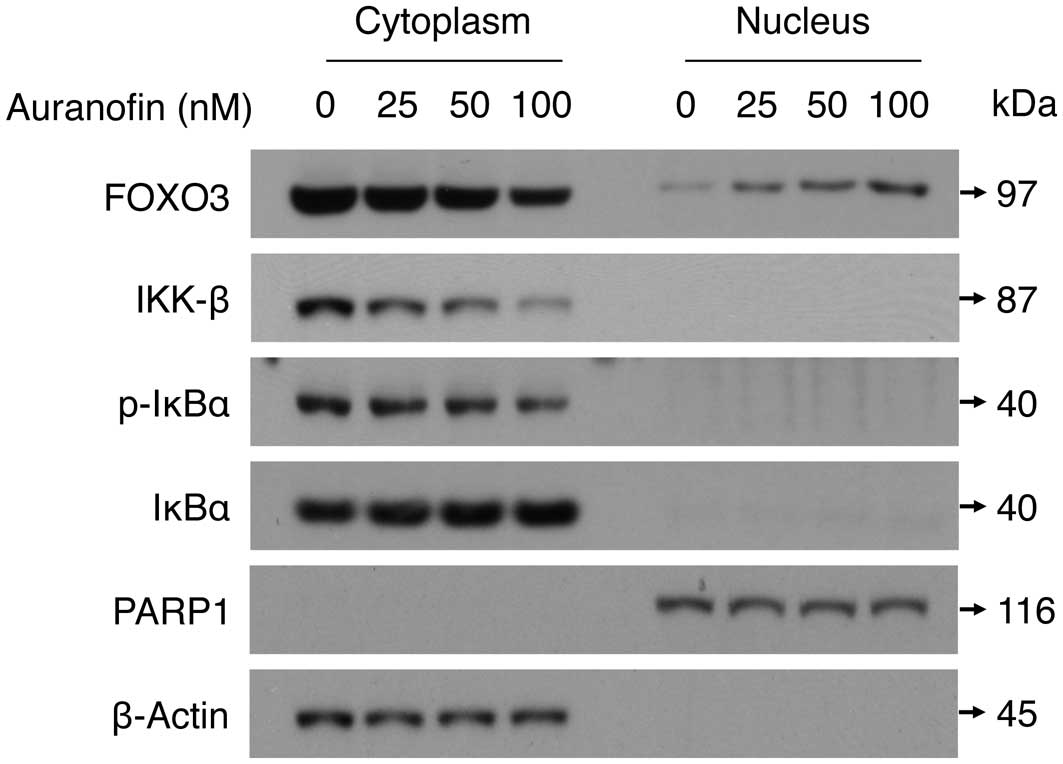

To elucidate the anticancer mechanism of auranofin

treatment against SKOV3 cells, we carried out western blot analyses

with cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts that had been fractionated

from SKOV3 cells previously treated with auranofin. We showed that

auranofin treatment (0, 25, 50 and 100 nM for 48 h) decreased the

expression level of IKK-β protein in the cytoplasm in a

dose-dependent manner. These data were confirmed by a parallel

decrease of the phosphorylation level of IκBα, which is a

well-known substrate of IKK-β, while the total amount of IκBα

protein was not affected by auranofin treatment (Fig. 6). At the same time, the level of

the cytoplasmic FOXO3 protein was decreased by auranofin treatment,

while the level of the nuclear FOXO3 protein was significantly

increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6). These results suggest that

auranofin may display its anticancer effect through downregulation

of IKK-β, which then triggers the translocation of the FOXO3

protein from the cytoplasm into the nucleus of ovarian cancer

cells.

Auranofin promotes apoptosis in SKOV3

cells in a FOXO3-dependent manner

To examine the role of FOXO3 in auranofin-induced

apoptosis in SKOV3 cells, we silenced FOXO3 expression in SKOV3

cells and analyzed the protein status of PARP1, caspase-3, Bax,

Bim, Bcl-2 and FOXO3 using western blot assays. Interestingly,

knockdown of FOXO3 expression in SKOV3 cells significantly

attenuated the caspase-3-mediated cleavage of PARP1 and caspase-3

proteins and reduced the expression levels of Bax and Bim, extra

large (EL) isoform, when these cells were treated with auranofin

(Fig. 7). In contrast, silencing

FOXO3 decreases the repressive effect of auranofin on Bcl-2

expression. Collectively, these results suggest that FOXO3 may play

an essential role in promoting the caspase-3-mediated apoptosis

after auranofin treatment in SKOV3 cells.

Discussion

FOXO3 has received great attention as a potential

prognostic biomarker for overall survival in patients with cancer

because several clinical studies with primary tumor specimens have

indicated that FOXO3′s nuclear exclusion or downregulation

correlates significantly with poor prognosis and survival in breast

and ovarian carcinomas (12,32–34).

These findings also suggest that small molecules that can induce

nuclear localization (activation) of FOXO3 in cancer cells may

become promising antitumor chemotherapeutic drugs. The promotion of

nuclear localization of the FOXO transcription factors by

gold-containing compounds such as auranofin has not been reported

and the roles of FOXO transcription factors in auranofin-mediated

cellular apoptosis have not been determined. In this study, our

results provide the first evidence that auranofin promotes the

FOXO3 protein to translocate from the cytoplasm into the nucleus,

where it upregulates the expression of the target genes Bax and Bim

and downregulates the expression of Bcl-2 (an important gene

regulating cell survival) in ovarian cancer cells. Because this

phenomenon is discovered in a p53-null cell line SKOV3, it suggests

that activation of FOXO3, Bax and Bim by auranofin may be through a

mechanism independent of p53. It is known that the tumor suppressor

p53 plays a key role in genotoxic stress responses including repair

of DNA damage, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, which are

complicated and mostly through a p53-dependent pathway (38–40).

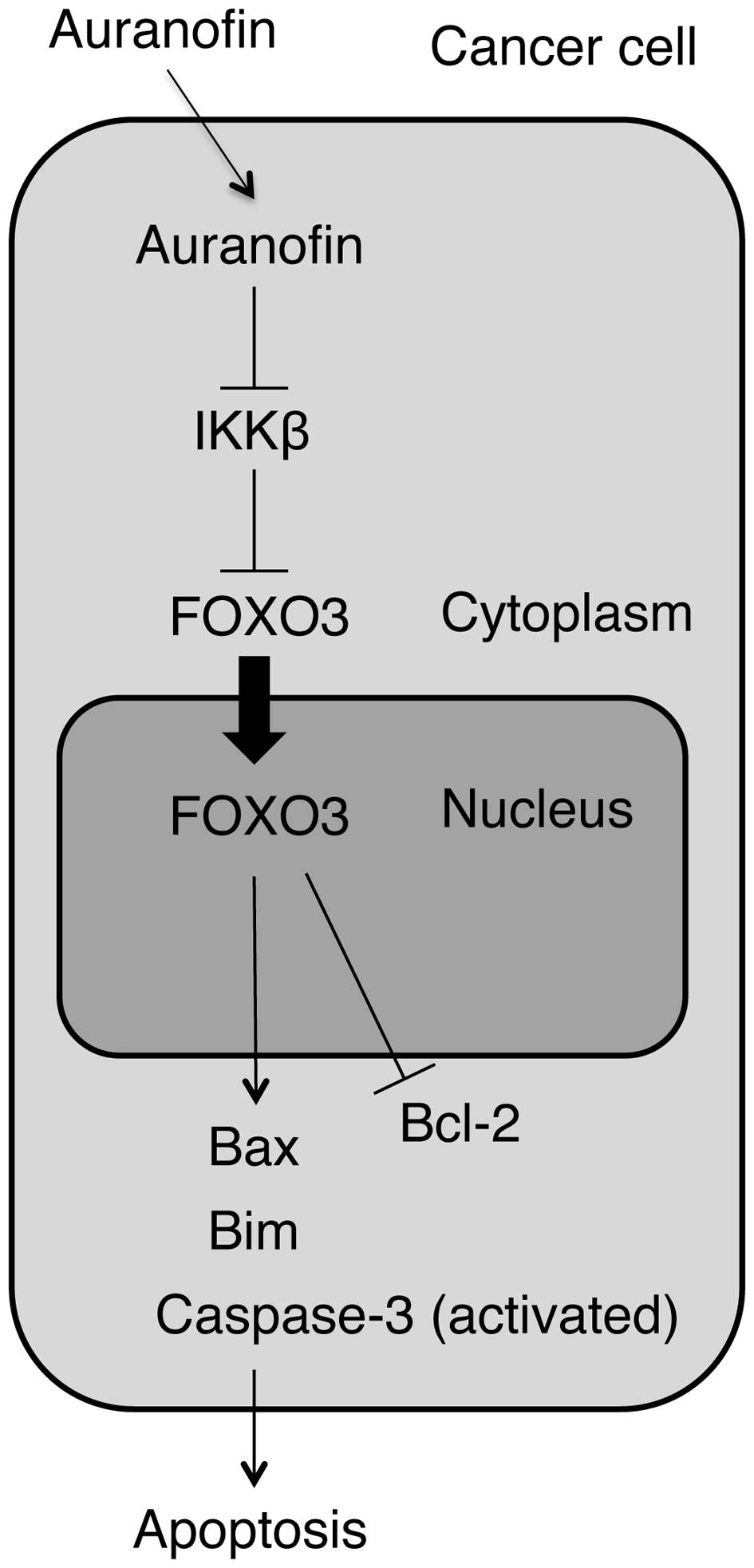

Therefore, we propose a new mechanism by which FOXO3 induces

apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells in response to auranofin

treatment through upregulation of Bax and Bim and downregulation of

Bcl-2 in a p53-independent manner (Fig. 8).

We found that auranofin treatment increased the

cleavage of PARP1 and caspase-3 in SKOV3 cells, while the level of

parental caspase-3 protein appear to be not significantly affected

by auranofin treatment (Figs. 5A

and 7). These results suggest that

auranofin may exhibit caspase-3-mediated apoptotic effect through

the activation of caspase-3 protein instead of through the

upregulation of caspase-3 expression in SKOV3 cells. Interestingly,

silencing the expression of FOXO3 in SKOV3 cells significantly

reduced the caspase-3-mediated cleavage of PARP1 and caspase-3

proteins (Fig. 7). Currently,

there is no literature to our knowledge that demonstrates FOXO3 is

required for the caspase-3-mediated cleavage of PARP1 and caspase-3

proteins and for auranofin-induced apoptotic signaling in cancer

cells. However, it remains largely unknown how FOXO3 regulates the

activation of caspase-3 protein in cancer cells in response to

auranofin treatment. It is of interest to further elucidate the

molecular mechanisms governing the control of the FOXO3-mediated

activation of caspase-3 protein in promoting the apoptotic

signaling pathways in cancer cells.

As an anti-rheumatoid arthritis agent, auranofin has

been shown to inhibit the activation of NF-κB by blocking IKK

activity in the LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 mouse macrophages

(8). In this study, our results

provide initial evidence of the anticancer effect of auranofin on

human ovarian cancer cells, in which auranofin treatment

downregulates the expression of IKK-β and reduces the level of

phospho-IκBα (p-IκBα) (Fig. 6).

Using the mutant forms of IKK-α and IKK-β subunits, Jeon et

al suggest a possible inhibitory mechanism to explain how

auranofin inhibited IKK activity in vitro (8). According to their report, a

substitution of cystine-179 of IKK-β with alanine (mutant

IKK-β-179A) made IKK-β resistant to inhibition by auranofin.

However, a similar protective effect was not observed with IKK-α

mutant. This result indicates that auranofin inhibited the two

subunits of IKK in a different mode and that the inhibition of IKK

activation induced by inflammatory signals in the auranofin-treated

cells may be via its interaction with cystine-179 of IKK-β. It will

be interesting to examine whether or not auranofin treatment

exhibits an inhibitory effect on mutant IKK-β-179A activity in

human cancer cells. Previously, our laboratory identified a novel

mechanism by which cancer cells can impair the tumor suppressive

function of FOXO3 protein by the oncogenic IKK-β-mediated

phosphorylation of the serine-644 residue in FOXO3 (FOXO3-pS644)

protein that leads to the translocation of FOXO3 from the nucleus

into the cytoplasm in cancer cells (11,12).

Subsequently, βTrCP1, an E3 Ub-ligase, interacts with the

FOXO3-pS644 protein and induces the Ub-mediated degradation of

FOXO3, resulting in the promotion of tumorigenesis and tumor growth

in vivo (11). This

IKK-β-mediated tumorigenic mechanism is consistent with and

supports our current finding that auranofin treatment can

downregulate the expression of IKK-β and promote FOXO3 nuclear

localization to regulate the expression of its downstream target

genes, resulting in the suppression of cell survival/growth and the

promotion of cellular apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells.

From the standpoint of cancer therapy, the initial

standard surgical management certainly plays an important and

essential role in ovarian cancer treatment. Most patients will have

appropriate surgical staging followed by optimal surgical

cytoreduction, with the goal being to remove all gross disease

before starting chemotherapy (2).

There are a number of important issues to be resolved in the

management of ovarian cancer that relates to surgery, including the

role of surgical interval cytoreduction, as well as the role of

second-look laparotomy (3). There

are basically three initial chemotherapy options considered the

standard of care at the present time for the treatment of ovarian

cancer. The first is the use of carboplatin and paclitaxel. The

second is a cisplatin and paclitaxel regimen. The third is the use

of a carboplatin and docetaxel regimen. Unfortunately, in the

second-line setting for the treatment of ovarian cancer, we have

far fewer encouraging data based upon randomized controlled trials

that give us definitive answers as to optimal management in the

malignancy. A considerable number of patients harbor ovarian tumor

refractory to these therapies and the majority of the initially

responsive tumors become resistant to treatments (41). Thus, the development of novel

targeted therapy that retains activity against

chemotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer is an unmet medical need.

Since auranofin is an FDA-approved small-molecule drug, it can be

expedited for future clinical trials as a promising anticancer

therapeutics and save time and money for the required pre-clinical

investigation and toxicity testing for new compounds (42).

Finally, further investigation of the signaling

mechanisms by which auranofin downregulates the expression of

antiapoptotic proteins IKK-β and Bcl-2 that in turn contributes to

tumor cell survival/growth may provide new cellular targets that

can be exploited therapeutically. On the other hand, further

elucidation of the molecular mechanisms underlying the

FOXO3-mdiated pro-apoptotic signaling pathways induced by auranofin

is necessary for understanding the molecular basis of auranofin

anticancer activity and its application as a new anticancer

therapy.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Freidenrich Center for Translational

Research for generously providing support. This study was supported

in part by R01 grant CA113859 (to M.C.T.H.) from the National

Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, the 2012

Developmental Cancer Research Award from Stanford Cancer Institute

(to M.C.T.H.), a grant 02-2013-051 from the Avon Foundation for

Women (to M.C.T.H.), and the 2012 Ann Schreiber Research Award from

the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (to S.H.P.).

References

|

1

|

Siegel R, Naishadham D and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 62:10–29. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Banerjee S and Kaye SB: New strategies in

the treatment of ovarian cancer: current clinical perspectives and

future potential. Clin Cancer Res. 19:961–968. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Shigetomi H, Higashiura Y, Kajihara H and

Kobayashi H: Targeted molecular therapies for ovarian cancer: an

update and future perspectives. Oncol Rep. 28:395–408.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Snyder RM, Mirabelli CK and Crooke SJ: The

cellular pharmacology of auranofin. Semin Arthritis Rheum.

17:71–80. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Madeira JM, Gibson DL, Kean WF and

Klegeris A: The biological activity of auranofin: implications for

novel treatment of diseases. Inflammopharmacology. 20:297–306.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Columbo M, Galeone D, Guidi G,

Kagey-Sobotka A, Lichtenstein LM, Pettit GR and Marone G:

Modulation of mediator release from human basophils and pulmonary

mast cells and macrophages by auranofin. Biochem Pharmacol.

39:285–2891. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Rigobello MP, Scutari G, Boscolo R and

Bindoli A: Induction of mitochondrial permeability transition by

auranofin, a gold(I)-phosphine derivative. Br J Pharmacol.

136:1162–1168. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Jeon KI, Jeong JY and Jue DM:

Thiol-reactive metal compounds inhibit NF-κB activation by blocking

IκB kinase. J Immunol. 164:5981–5989. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kim IS, Jin JY, Lee IH and Park SJ:

Auranofin induces apoptosis and when combined with retinoid acid

enhances differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukaemia cells in

vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 142:749–755. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Park SJ and Kim IS: The role of p38 MAPK

activation for auranofin-induced apoptosis of human promyelocytic

leukaemia HL-60 cells. Br J Pharmacol. 146:506–513. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tsai WB, Chung YM, Zou Y, Park SH, Xu Z,

Nakayama K, Lin SH and Hu MC: Inhibition of FOXO3 tumor suppressor

function by βTrCP1 through ubiquitin-mediated degradation in a

tumor mouse model. PLoS One. 5:e111712010.

|

|

12

|

Hu MC, Lee DF, Xia W, Golfman LS, Ou-Yang

F, Yang JY, Zou Y, Bao S, Hanada N, Saso H, Kobayashi R and Hung

MC: IkappaB kinase promotes tumorigenesis through inhibition of

forkhead FOXO3a. Cell. 117:225–237. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Katoh M and Katoh M: Human FOX gene

family. Int J Oncol. 25:1495–1500. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Alvarez B, Martinez AC, Burgering BM and

Carrera AC: Forkhead transcription factors contribute to execution

of the mitotic programme in mammals. Nature. 413:744–747. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Furukawa-Hibi Y, Kobayashi Y, Chen C and

Motoyama N: FOXO transcription factors in cell-cycle regulation and

the response to oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 7:752–760.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo

P, Hu LS, Anderson MJ, Arden KC, Blenis J and Greenberg ME: Akt

promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead

transcription factor. Cell. 96:857–868. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Sunters A, Fernández de Mattos S, Stahl M,

Brosens JJ, Zoumpoulidou G, Saunders CA, Coffer PJ, Medema RH,

Coombes RC and Lam EW: FOXO3 transcriptional regulation of Bim

controls apoptosis in paclitaxel-treated breast cancer cell lines.

J Biol Chem. 278:49795–49805. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Fu Z and Tindall DJ: FOXOs, cancer and

regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene. 27:2312–2319. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chung YM, Park SH, Tsai WB, Wang SY, Ikeda

MA, Berek JS, Chen DJ and Hu MC: FOXO3 signalling links ATM to the

p53 apoptotic pathway following DNA damage. Nat Commun. 3:10002012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tran H, Brunet A, Grenier JM, Datta SR,

Fornace AJ Jr, DiStefano PS, Chiang LW and Greenberg ME: DNA repair

pathway stimulated by the forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a

through the Gadd45 protein. Science. 296:530–534. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Tsai WB, Chung YM, Takahashi Y, Xu Z and

Hu MC: Functional interaction between FOXO3 and ATM regulates DNA

damage response. Nat Cell Biol. 10:460–467. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yang J-Y, Xia W and Hu MC: Induction of

FOXO3a and Bim expression in response to ionizing radiation. Int J

Oncol. 29:643–648. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sunters A, Madureira PA, Pomeranz KM,

Aubert M, Brosens JJ, Cook SJ, Burgering BM, Coombes RC and Lam EW:

Paclitaxel-induced nuclear translocation of FOXO3 in breast cancer

cells is mediated by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and Akt. Cancer Res.

66:212–220. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Nemoto S, Fergusson MM and Finkel T:

Nutrient availability regulates SIRT1 through a forkhead-dependent

pathway. Science. 306:2105–2108. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Greer EL and Brunet A: FOXO transcription

factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression.

Oncogene. 24:7410–7425. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Seoane J, Le HV, Shen L, Anderson SA and

Massagué J: Integration of Smad and forkhead pathways in the

control of neuroepithelial and glioblastoma cell proliferation.

Cell. 117:211–223. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Paik JH, Kollipara R, Chu G, Ji H, Xiao Y,

Ding Z, Miao L, Tothova Z, Horner JW, Carrasco DR, Jiang S,

Gilliland DG, Chin L, Wong WH, Castrillon DH and DePinho RA: FoxOs

are lineage-restricted redundant tumor suppressors and regulate

endothelial cell homeostasis. Cell. 128:309–323. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Miyamoto K, Araki KY, Naka K, Arai F,

Takubo K, Yamazaki S, Matsuoka S, Miyamoto T, Ito K, Ohmura M, Chen

C, Hosokawa K, Nakauchi H, Nakayama K, Nakayama KI, Harada M,

Motoyama N, Suda T and Hirao A: FOXO3 is essential for maintenance

of the hematopoietic stem cell pool. Cell Stem Cell. 1:101–112.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Huang H and Tindall DJ: FOXO factors: a

matter of life and death. Future Oncol. 2:83–89. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Hu MC and Hung MC: Role of IkappaB kinase

in tumorigenesis. Future Oncol. 1:67–78. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Eijkelenboom A and Burgering BM: FOXOs:

signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 14:83–97. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lu M, Zhao Y, Xu F, Wang Y, Xiang J and

Chen D: The expression and prognosis of FOXO3a and Skp2 in human

ovarian cancer. Med Oncol. 29:3409–3915. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Fei M, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Lu M, Cheng C,

Huang X, Zhang D, Lu J, He S and Shen A: Low expression of Foxo3a

is associated with poor prognostic in ovarian cancer patients.

Cancer Invest. 27:52–59. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Habashy HO, Rakha EA, Aleskandarany M,

Ahmed MA, Green AR, Ellis IO and Powe DG: FOXO3a nuclear

localization is associated with good prognosis in luminal-like

breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 129:11–21. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Nicholson DW: Caspase structure,

proteolytic substrates, and function during apoptotic cell death.

Cell Death Differ. 6:1028–1042. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S,

Poirier GG and Earnshaw WC: Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase

by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature. 371:346–347.

1994. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kumari SR, Mendoza-Alvarez H and

Alvarez-Gonzalez R: Functional interactions of p53 with

poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) during apoptosis following DNA

damage: covalent poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of p53 by exogenous PARP

and noncovalent binding of p53 to the M(r) 85,000 proteolytic

fragment. Cancer Res. 58:5075–5078. 1998.

|

|

38

|

Carvajal LA and Manfredi JJ: Another fork

in the road - life or death decisions by the tumour suppressor p53.

EMBO Rep. 14:414–421. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Yoshida K and Miki Y: The cell death

machinery governed by the p53 tumor suppressor in response to DNA

damage. Cancer Sci. 101:831–835. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Das S, Boswell SA, Aaronson SA and Lee SW:

P53 promoter selection: choosing between life and death. Cell

Cycle. 7:154–157. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Fung-Kee-Fung M, Oliver T, Elit L, Oza A,

Hirte HW and Bryson P: Optimal chemotherapy treatment for women

with recurrent ovarian cancer. Curr Oncol. 14:195–208. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Chong CR and Sullivan DJ Jr: New uses for

old drugs. Nature. 448:645–646. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|