Introduction

Lung cancer has been and remains one of the most

common malignancy in the world with an estimated 1.6 million new

cases per annum (1). Small-cell

lung cancer (SCLC), which constitutes between 10 and 15% of all

lung neoplasm and is different from non-small-cell lung cancer

(NSCLC) types in that it has neuroendocrine features, grows more

rapidly, spreads earlier and has a lower cure rate (1,2).

Furthermore, SCLC metastasizes rapidly to distant sites within the

body and is most often discovered after it has spread extensively

(1,3).

Whilst SCLC is initially sensitive to chemotherapy

and radiotherapy, relapse is almost inevitable and the efficacy of

treatment beyond first-line therapy diminishes as it becomes

increasingly resistant to treatment (1–3).

Although continuous efforts to improve clinical outcomes in

patients with SCLC by progressing clinical trials with novel

promising drugs are ongoing, platinum (such as cisplatin)-etoposide

doublets still represent the gold standard of a first-line therapy

(1). Furthermore, the 5-year

survival rates have not improved significantly over the last 40

years and have currently plateaued, although advance in diagnosis

and treatment have resulted in improved survival of other

solid-tumor malignancies (1).

Therefore, there is an obvious need to develop new therapeutic

strategies for SCLC.

Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PDTC), a thiol compound

derived from dithiocarbamates, was initially described as an

antioxidant agent and reported to induce cytotoxicity in some tumor

cell lines (4,5). On the other hand, PDTC has been

described to act as a pro-oxidant agent (6–9). In

fact, its pro-oxidant activity has been demonstrated to induce

growth inhibition and cell death in rat cortical astrocytes

(6), a human pancreatic

adenocarcinoma cell line, PaGa44 (10) and promyelocytic leukemic cell line,

HL-60 (11), respectively. It

should be noted that PDTC has been demonstrated to sensitize human

cervical cancer line and metastatic renal cell carcinoma to

cisplatin (12,13). As mentioned above, cisplatin-based

regimens have become and remain the first-line treatment for SCLC

from the 1980s (14,15). Therefore, we hypothesize that PDTC

may be a promising candidate of adjunct therapeutic reagent for

SCLC. However, the effect of PDTC in SCLC cell lines, alone or in

combination with cisplatin, has not yet been investigated.

Increased intracellular Cu content has been

associated with PDTC-mediated cytotoxicity due to its ionophore

properties (6,9,11).

Furthermore, the presence of CuCl2 has been demonstrated

to potentiate the cytotoxic effects of PDTC in rat cortical

astrocytes and HL-60 cells (6,11).

Intracellular Cu homeostasis is well known to be maintained by Cu

transporters including copper-transporting P-type adenosine

triphosphatase (ATP7A) responsible for Cu efflux, and copper

transporter 1 (CTR1) responsible for Cu uptake (16). Moreover, ATP7A has been reportedly

associated with platinum drug resistance in various types of solid

tumors (16–18). It is especially noteworthy that

ATP7A plays a critical role in cisplatin-resistance of NSCLC, and

is a negative prognostic factor of NSCLC patients treated with

platinum-based chemotherapy (19–21).

However, to our knowledge, little is known about the expression of

Cu transporters in SCLC cell lines as well as the impact of PDTC on

their expression.

In the present study, we investigated first the

cytocidal effects of PDTC on SCLC cell lines in view of growth

inhibition, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis induction. We further

evaluated whether oxidative stress is involved in the cytocidal

effects by determining alterations in intracellular reactive oxygen

species (ROS) level along with expression levels of

oxidative-related genes. At the same time, the effect

N-acetyl-l-

cysteine (NAC), a free radical scavenger, on PDTC-mediated

cytotoxicity was also evaluated. We further investigated the

cytocidal effect of PDTC in combination with CuCl2 in

the presence or absence of bathocuproine disulfonate (BCPS), a

non-permeable copper-specific chelator, in order to verify whether

Cu is involved in the cytocidal effect. Importantly, we

investigated for the first time the effect of PDTC on the

expression levels of copper transporters such as ATP7A and CTR1,

and further evaluated the effects of cisplatin in combination with

non-toxic dose of PDTC on SCLC cell lines.

Materials and methods

Materials

PDTC, RPMI-1640 medium, CuCl2, NAC, and

ISOGEN (Wako Pure Chemical Industry, Osaka, Japan); fetal bovine

serum (FBS) (Nichirei Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan); agarose X (Nippon

Gene, Tokyo, Japan); dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA)

(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA); propidium iodide (PI),

ribonuclease A (RNaseA),

2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)

carbony]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT), BCPS and cisplatin

(Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were purchased from indicated

suppliers.

Cell culture and treatment

Human SCLC cell lines (NCI-H196 and NCI-H889) and

normal human embryonal lung fibroblast MRC-5 cells were obtained

from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA,

USA). SCLC cell lines and MRC-5 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640

medium and Eagle’s minimum essential medium (MEM), respectively,

supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml of penicillin

and 100 μg/ml of streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere

(5% CO2 in air). Cells were treated with indicated

concentrations of PDTC for the indicated time-points. In order to

investigate whether oxidative stress is involved in PDTC-induced

cytotoxicity, cells were treated with 0.3 or 1 μM PDTC in the

presence or absence of 1 or 2 mM NAC for 24 h. Moreover, in order

to clarify whether copper ions are implicated in the PDTC-induced

cytotoxicity, cells were treated with CuCl2 (10 μM) and

BCPS (50 μM) (a non-permeable copper-specific chelator), alone or

in combination, for 3 h prior to treatment with 0.1 and 0.3 μM PDTC

in the presence or absence of these reagents. Cells were also

treated with 5 μM cisplatin in the presence or absence of 0.1 μM

PDTC for 24 h to investigate whether PDTC sensitize SCLC cell lines

to cisplatin. Cell viability was measured by the XTT assay as

described previously (22).

IC50 value of PDTC was ~0.3 μM calculated from the cell

proliferation inhibition curve of NCI-H196 cells after 24-h

treatment.

DNA fragmentation analysis

DNA fragmentation analysis was carried out according

to a method described previously (23). Briefly, DNA samples [~20 μg DNA/20

μl TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA)] and a Tracklt™

100 bp DNA Ladder (Invitrogen) as a DNA size marker were

electrophoresed, respectively, on a 2% agarose X gel, and

visualized by ethidium bromide staining, followed by viewing under

UV Light Printgraph (ATTO Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Cell cycle analysis

After treatment with the IC50 value of

PDTC at 0.3 μM for 24 h, cell cycle analysis was performed using a

FACSCanto flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, CA, USA) according to

methods reported previously with modifications (24,25).

A total of 10,000 events were acquired and Diva software and ModFit

LT™ Ver.3.0 (Verity Software House, ME, USA) were used to calculate

the number of cells at each sub-G1,

G0/G1, S and G2/M phase

fraction.

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain

reaction (RT-PCR) analysis

Total RNA isolation and complementary DNA were

prepared according to methods described previously with

modifications (23). Total RNA was

extracted from cells using an RNA extraction kit, ISOGEN.

Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 μg of RNA using 100 pmol

random primer and 50 U M-MLV RT in a total volume of 20 μl,

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. PCR was performed

according to the methods previously described (23) using a Takara Thermal Cycler MP

(Takara Shuzo Co., Osaka, Japan). DNA sequences of PCR primers and

optimal conditions for PCR are shown in Table I. PCR primers were purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich (Hokkaido, Japan). PCR products and 100 bp DNA Ladder

were electrophoresed on a 2% UltraPure™ agarose gel (Invitrogen),

respectively, and visualized by ethidium bromide staining, followed

by viewing under UV Light Printgraph. The relative expression

levels of target gene/β-actin gene were calculated as the ratios

against those at 0-time using ImageJ 1.46 m (Wayne Rasband,

USA).

| Table IRT-PCR analysis. |

Table I

RT-PCR analysis.

| A, PCR primers and

optimal numbers of PCR cycle |

|---|

|

|---|

| Target mRNA | | DNA sequence of PCR

primer | Optimal cycles |

|---|

| Cox-2 | Sense |

5′-TTCAAATGAGATTGTGGGAAAATTGCT-3′ | 36 |

| Antisense |

5′-AGATCATCTCTGCCTGAGTATCTT-3′ | |

| HO-1 | Sense |

5′-CCAGCAACAAAGTGCAAGATTC-3′ | 27 |

| Antisense |

5′-CTGCAGGAACTGAGGATGCTG-3′ | |

| Mn-SOD | Sense |

5′-GCACTAGCAGCATGTTGAGCCG-3′ | 27 |

| Antisense |

5′-CAGTTACATTCTCCCAGTTGATTAC-3′ | |

| Cu/Zn-SOD | Sense |

5′-GCCTAGCGAGTTATGGCGACGA-3′ | 27 |

| Antisense |

5′-GGCCTCAGACTACATCCAAGG-3′ | |

| Catalase | Sense |

5′-CAGATGGACATCGCCACATG-3′ | 27 |

| Antisense |

5′-AAGACCAGTTTACCAACTGGG-3′ | |

| GPx1 | Sense |

5′-TGGCTTCTTGGACAATTGCG-3′ | 27 |

| Antisense |

5′-CCACCAGGAACTTCTCAAAG-3′ | |

| β-actin | Sense |

5′-CCTTCCTGGGCATGGAGTCCTG-3′ | 24 |

| Antisense |

5′-GGAGCAATGATCTTGATCTTC-3′ | |

|

| B, Conditions for

PCR |

|

| Denaturation

reaction | Annealing

reaction | Extension

reaction |

|

|

|

|

| Target mRNA | Temperature

(°C) | Time (sec) | Temperature

(°C) | Time (sec) | Temperature

(°C) | Time (sec) |

|

| Cox-2 | 94 | 30 | 58 | 30 | 72 | 30 |

| HO-1 | 94 | 60 | 65 | 60 | 72 | 60 |

| Mn-SOD | 94 | 60 | 62 | 60 | 72 | 60 |

| Cu/Zn-SOD | 94 | 60 | 65 | 60 | 72 | 120 |

| Catalase | 94 | 60 | 55 | 120 | 72 | 180 |

| GPx1 | 94 | 60 | 55 | 120 | 72 | 180 |

| β-actin | 94 | 45 | 60 | 45 | 72 | 120 |

Measurement of intracellular ROS

levels

Intracellular ROS levels were analyzed using DCFH-DA

as a ROS-reactive fluorescence probe as described previously

(24,26). In brief, after treatment with 0.3

μM PDTC for 3 or 12 h, cells (1×106 cells) were

suspended in 1 ml of PBS with 5 mM DCFH-DA and incubated for 20 min

at 37°C. Next, cells were washed with PBS twice, and resuspended in

500 μl of 2 μg/ml PI/PBS. The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of

DCF green fluorescence from 3×104 cells were acquired

for flow cytometry analysis using a FACSCanto flow cytometer and

Diva software.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Student’s t-test and

p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Cytocidal effects of PDTC on SCLC cell

lines

After the treatment with various concentrations of

PDTC (0.1, 1 and 10 μM) for 24 h, a significant decrease in cell

viability was observed in a dose-dependent manner in NCI-H196 cells

with IC50 value of 0.3 μM (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, although PDTC

also exhibited dose-dependent cytotoxic activity against NCI-H889,

the IC50 value of PDTC could not be calculated from its

proliferation inhibition curve since >50% of cells survived even

when treated with the highest concentration of PDTC (10 μM)

(Fig. 1A), indicating NCI-H196 is

more sensitive to the cytotoxicity of PDTC compared to NCI-H889.

Moreover, no apparent cytotoxic activity was observed in normal

human embryonal lung fibroblast MRC-5 when treated with the same

range of PDTC concentrations even for 48 h (Fig. 1B). No DNA fragmentation was

observed in either SCLC cell line, indicating no involvement of

apoptosis induction in the PDTC-mediated cytotoxicity (Fig. 1C).

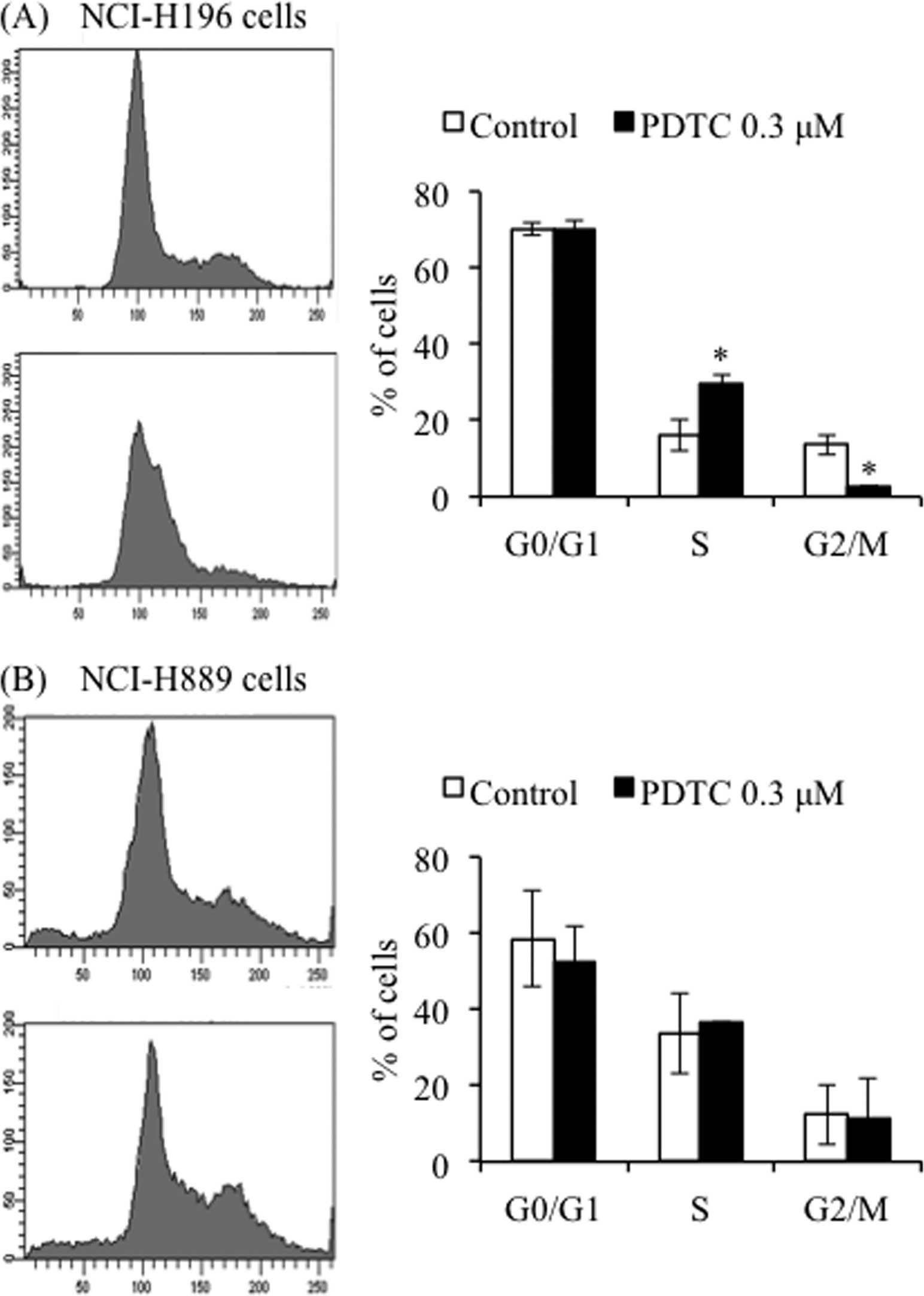

Effects of PDTC on cell cycle of SCLC

cell lines

S phase arrest along with a significant decrease in

the number of cells in G2/M phase was observed in

NCI-H196 cells after treatment with the IC50 value of

PDTC at 0.3 μM for 24 h (Fig. 2A).

However, no apparent alterations of cell cycle were observed in

NCI-H889 cells under the same treatment conditions (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, in agreement with

the results presented in Fig. 1C,

no significant accumulation of cells in sub-G1 phase was

observed in the treated cells (Fig.

2).

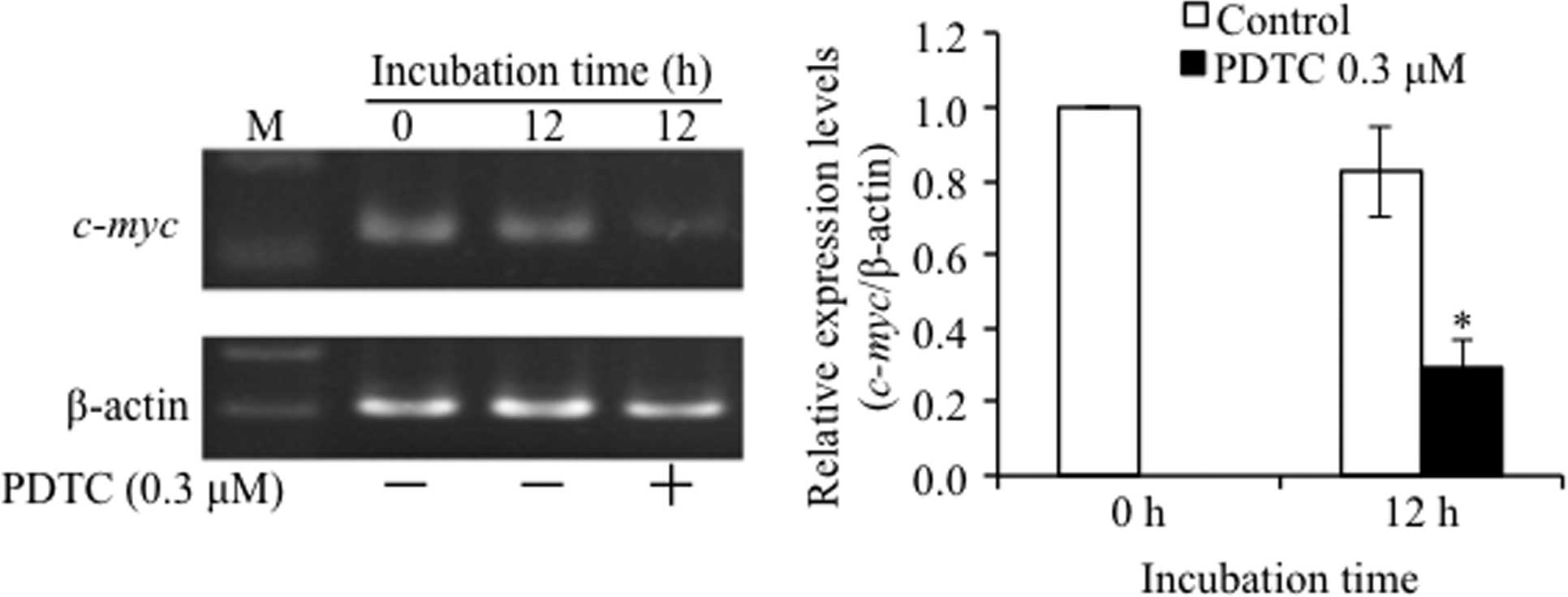

Suppression of c-myc expression in

PDTC-treated NCI-H196 cells

A large body of physiological evidence has shown

that either upregulation or downregulation of c-myc activity

has profound consequences on cell cycle progression (27,28).

Therefore, the alteration of c-myc gene expression was

evaluated in NCI-H196 cells after treatment with 0.3 μM of PDTC for

12 h. As shown in Fig. 3, the

expression level of c-myc gene was significantly suppressed

in PDTC-treated cells when compared to that in untreated cells.

Furthermore, similar phenomena were not observed in NCI-H889 cells

(data not shown).

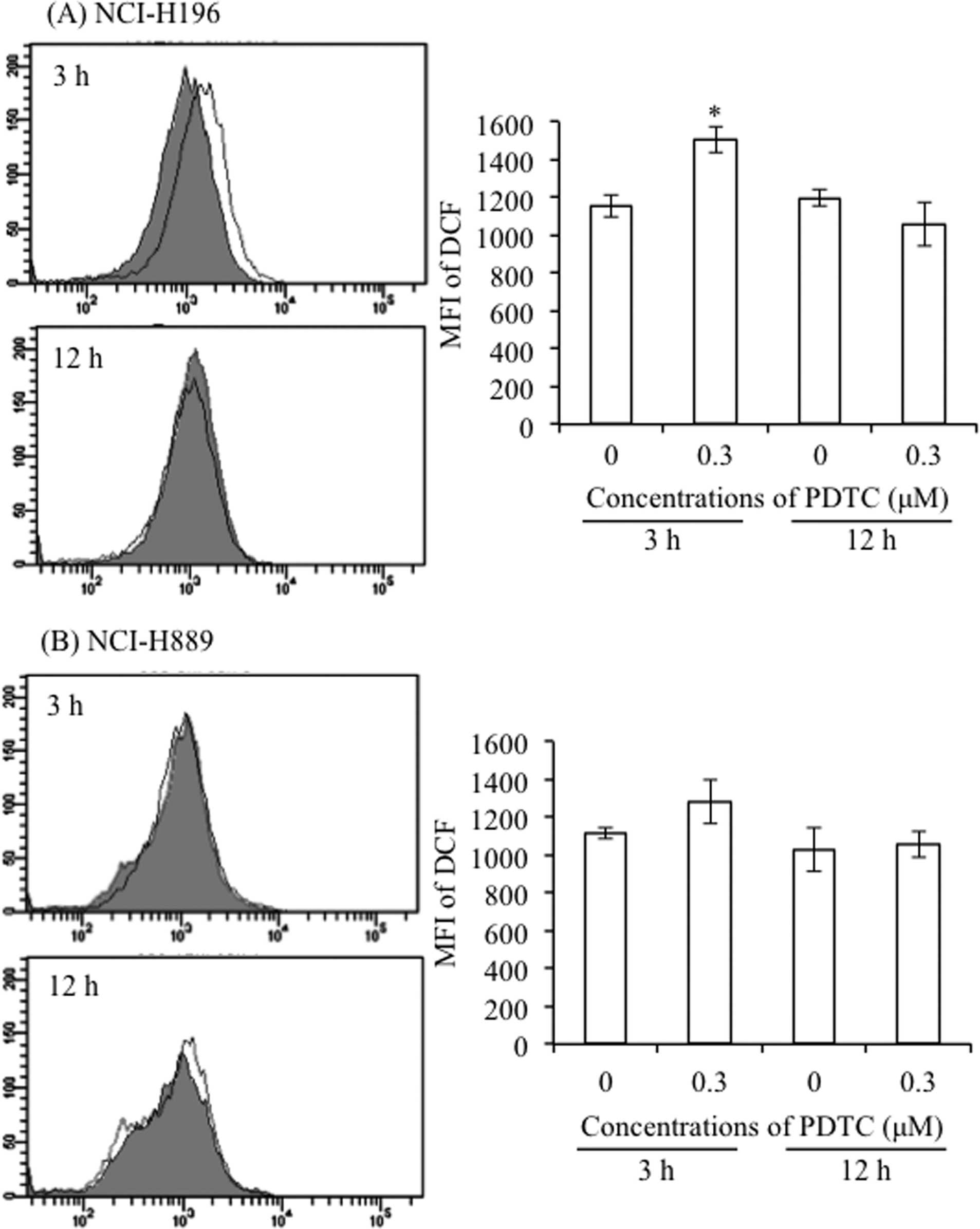

Alteration of intracellular ROS levels in

PDTC-treated SCLC cell lines

Since the pro-oxidant activity of PDTC has been

described to induce growth inhibition and cell death in different

types of cancer cells (10,11),

intracellular ROS levels were evaluated in both SCLC cell lines

after treatment with 0.3 μM of PDTC for 3 and 12 h. FACS analysis

using DCFH-DA as a ROS-reactive fluorescence probe showed that a

transient increase in the intracellular ROS levels was observed in

NCI-H196 cells at 3-h post-treatment, followed by restoration to

the control levels at 12-h post-treatment (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, a slight, but

non-significant, increase in the accumulation of intracellular ROS

was observed in NCI-H889 cells after treatment with PDTC for 3 h

(Fig. 4B).

Expression profiles of oxidative

stress-related mRNAs in PDTC-treated NCI-H196 cells

Since a transient increase in the intracellular ROS

levels was observed in PDTC-treated NCI-H196 cells, expression

profiles of oxidative stress-related gene mRNAs were evaluated in

the cells after treatment with 0.3 and 1 μM of PDTC for 1, 3, 6 and

12 h, respectively. It should be noted that the expression profiles

of these gene mRNAs in cells treated with 0.3 μM PDTC were very

similar to those in cells treated with 1 μM PDTC. As shown in

Fig. 5A and B, a significant

increase in the expression level of Cox-2, which is known to play a

central role in ROS production (29), was observed 6 h after treatment

with PDTC, and the increase continued up to 12 h. Furthermore, the

expression of HO-1, which is closely associated with oxidative

stress mediated cellular damage (30,31),

was significantly induced from as early as 3 h after the treatment

with PDTC. In comparison to untreated cells, the level of HO-1 gene

expression increased approximately 6- or 9-fold after 6- and 12-h

treatment, respectively. Moreover, a significant decrease in the

expression levels of Mn-SOD and Cu/Zn-SOD was observed 3 h after

treatment with PDTC, and continued up to 12 h. A slight but

significant downregulation in catalase expression was observed 1 h

after treatment with PDTC, followed by a substantial decrease at 3-

and 6-h post-treatment. Similar to the expression of other

antioxidant enzymes, the expression levels of GPx1 were also

significantly downregulated at 6- and 12-h post-treatment,

respectively. Moreover, PDTC-mediated alterations in expression

level of the above-mentioned oxidative-related genes were abolished

by the addition of 2 mM NAC, a free radical scavenger (Fig. 5C). However, similar phenomena were

not observed in NCI-H889 cells, except the behavior of HO-1 gene

expression (data not shown).

Blocking of PDTC-induced cytotoxicity by

NAC

To further verify whether oxidative stress is

responsible for the cytotoxicity of PDTC against SCLC cell lines,

we investigated the effects of NAC on the PDTC-induced cytotoxicity

in NCI-H196 cells. As shown in Fig.

6A, dose-dependent cytotoxic effects of PDTC on NCI-H196 cells

were reconfirmed by the reduction in cell viability. Furthermore,

the cells treated with 0.3 μM PDTC for 24 h displayed apparent

morphological changes such as shrinkage, spherical morphology, and

detachment of the cells (Fig. 6B).

In contrast, PDTC-induced reduction in cell viability and

morphological changes were almost completely abrogated by the

addition of 1 or 2 mM NAC (Fig.

6).

Inhibition of enhanced cytotoxicity of

PDTC in combination with CuCl2 by BCPS

As shown in Fig. 7,

no cytocidal effects was observed in either of the SCLC cell lines

after treatment with 0.1 μM PDTC alone for 24 h, consistent with

the results in Fig. 1. However, a

significant decrease in cell viability was observed in both cells

after treatment with 0.1 μM PDTC in combination with 10 μM

CuCl2. Furthermore, a much stronger cytocidal effect

against NCI-H196 cells was confirmed. Intriguingly, the addition of

50 μM BCPS, a non-permeable copper-specific chelator, completely

abrogated the enhanced cytotoxicity of PDTC in combination with

CuCl2. Moreover, after treatment 0.3 μM PDTC alone for

24 h, a significant decrease in the cell viability was observed in

NCI-H196, but not in NCI-H889, reconfirming that NCI-H196 is more

sensitive to the cytotoxicity of PDTC. Similarly, the addition of

50 μM BCPS completely abrogated 0.3 μM PDTC-mediated cytotoxicity

in NCI-H196 cells. When both cells were treated with 0.3 μM PDTC

combined with 10 μM CuCl2, the enhanced cytotoxicity was

significantly abrogated by the addition of 50 μM BCPS. Moreover, no

alteration in cell viability was observed in the cells when treated

with BCPS and CuCl2, either alone or in combination.

Downregulation of expression levels of

ATP7A in PDTC-treated NCI-H196 cells

It has been demonstrated that cellular oxidative

stress induced by PDTC may be attributed to increased intracellular

concentrations of Cu (9,32). Indeed, it has been clarified that

treatment with a relatively high concentration of PDTC (10–100 μM)

markedly increased an intracellular concentrations of Cu, and that

the combination of PDTC (0.1–1 μM) with Cu (1 μM) also

significantly increased the concentrations of intracellular Cu in

parallel with an enhanced cytotoxicity in HL-60 cells and rat

thymocytes, respectively (9,11).

Therefore, the expression levels of ATP7A responsible for Cu

efflux, and CTR1 responsible for Cu uptake were investigated in

PDTC-treated SCLC cell lines. As shown in Fig. 8, in comparison to control at 24-h

time-point, almost no alteration in the expression level of CTR1

was observed in the cells after treatment with 0.3 μM PDTC for 24

h, although there was a trend showing an increase in its expression

level. On the other hand, the expression level of ATP7A

significantly decreased by >50% in NCI-H196 cells, whereas

displayed a slight, but not significant, increase in NCI-H889

cells. Interestingly, the expression level of two Cu transporters

appeared to be affected by medium change, since notable differences

in their expression levels were observed in control groups between

0- and 24-h time-points.

Enhancement of cytotoxicity in NCI-H196

cells treated with combination of cisplatin and PDTC

A correlation between the expression level of Cu

transporters and the degree of the acquired resistance to platinum

drug, known as a first line treatment for SCLC patients, suggested

that Cu transporters play critical roles in regulation of

sensitivity to platinum drugs (16,19–21).

Since the results presented in Fig.

8 showed that treatment with a relatively low concentration of

PDTC significantly downregulated the expression level of ATP7A in

NCI-H196 cells, an investigation into the effects of the

combination of cisplatin and PDTC on the cells were followed in the

study. After the treatment of NCI-H196 cells with various

concentrations of cisplatin alone for 24 h, the relative cell

viabilities were 85, 70 and 25% of control for 5, 10, and 100 μM

cisplatin, respectively. Moreover, a significant decrease in the

cell viability was only observed in NCI-H889 cells when treated

with 100 μM cisplatin (the value of cell viability, 51%).

Intriguingly, treatment with 5 μM cisplatin in combination with

non-toxic dose of 0.1 μM PDTC decreased the cell viability of

NCI-H196 by ~50%, showing a synergistic effect in augmenting

cytotoxicity of cisplatin (Fig.

9). On the other hand, a slight decrease in the cell viability

of NCI-H889 was observed (Fig.

9).

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that PDTC

exhibited a much stronger dose-dependent cytotoxic activity against

NCI-H196 compared to NCI-H889 cells. Furthermore, S phase arrest

along with a significant decrease in the number of cells in

G2/M phase, but not DNA fragmentation, was observed in

NCI-H196 cells. These results suggest that PDTC induces

cytotoxicity in the SCLC cells via cell cycle arrest in the

S-phase, rather than apoptosis induction. Similar phenomena have

also been observed in PDTC-treated human pancreatic adenocarcinoma

cell line, PaCa44 (10).

Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that NCI-H889 is more

sensitive to the cytotoxicity of ABT-737, a small-molecule

inhibitor of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bcl-w (33), compared to NCI-H196, due to

NCI-H889 having much higher Bcl-2 gene copy number (34). Therefore, the differential

sensitivities of the two SCLC cell lines to PDTC may not be

attributed to the different amounts of Bcl-2 gene number.

Furthermore, consistent with previous findings showing that normal

primary cells including human bone marrow CD34+ cells

and fibroblasts are insensitive to the cytocidal effects of PDTC

(10,35), we demonstrated that no alteration

was observed in cell viability of the human MRC-5 embryonal lung

fibroblasts when treated with toxic doses of PDTC in SCLC cell

lines. These findings imply that normal cells are equipped with

mechanisms by which they respond differently to PDTC effects with

respect to tumor cells, providing further supportive evidence for

the use of PDTC in wide clinical practice.

We further demonstrated that suppression of

c-myc gene expression was observed in PDTC-treated NCI-H196

cells. It has been demonstrated that c-Myc is a critical protein in

controlling proliferation, differentiation and survival of cancer

cells (27,28,36).

It was demonstrated (28) that

c-Myc downregulation caused by resveratrol, a plant polyphenol

naturally occurring in grapes with chemopreventive properties

(37), resulted in cell cycle

arrest at S phase and apoptotic cell death in human medulloblastoma

cells. It was further clarified that transfection of c-myc

directed antisense oligonucleotides to the cells reduced

c-myc expression, and consequently inhibited cell growth

concomitant with cell cycle arrest in the S phase (28). Taken together, we suggested that

c-myc downregulation is a critical molecular event in

PDTC-mediated cell cycle arrest of NCI-H196 cells. In fact, a

previous report demonstrated that treatment of leukemic cell line

U-937 with 100 μM of PDTC markedly downregulated the expression

level of c-myc, associated with cell growth inhibition

(38). Furthermore, Donadelli

et al have demonstrated that PDTC induced

P21WAF1/CIP1 expression post-transcriptionally

via a ROS/ERK mediated mechanism in PaCa44 cells, and consequently

resulted in cell cycle arrest at S phase (10). It should be noted that c-myc

has been reported to be a negative regulator of

P21WAF1/CIP1 expression in lung cancer cells

(39). Therefore, further studies

may be needed to clarify the molecular details of correlation

between c-myc and P21WAF1/CIP1 in

PDTC-treated SCLC cell lines.

We also demonstrated that PDTC induced accumulation

of intracellular ROS in NCI-H196 cells, paralleled with an

alteration of oxidative stress-related gene expression, suggesting

that PDTC acts as a pro-oxidant agent in the cells, although the

antioxidant activity of PDTC has been reported to induce

cytotoxicity in some tumor cell lines, such as colorectal (4) and prostatic carcinoma cells (5). In line with these results, the

addition of NAC, a free radical scavenger, not only abolished

PDTC-triggered alterations of the above-mentioned oxidative

stress-related gene expression but also almost completely abrogated

PDTC-induced reduction in cell viability and morphological changes

associated with cell damage.

In agreement with a previous report showing that

combination treatment with CuCl2 and PDTC enhanced the

cytocidal effects against HL-60 cells (11), we also demonstrated that a

significant decrease in cell viability was observed in SCLC cell

lines after treatment with 0.1 μM PDTC in combination with 10 μM

CuCl2, either of which was a non-toxic dose.

Interestingly, BCPS, a non-permeable copper-specific chelator,

completely abrogated the enhanced cytotoxicity of PDTC in

combination with CuCl2. In this regard, BCPS has been

demonstrated to block the penetration of Cu into cells and prevent

Cu overload, and consequently protect HL-60 cells from the

cytotoxicity caused by PDTC/Cu complex (11). Furthermore, it has been

demonstrated that cellular oxidative stress induced by PDTC may be

attributed to an increased intracellular concentrations of Cu due

to ionophore activity of PDTC (6,9,32).

Taking these previous results and our observations into account, we

suggested that PDTC induced cytocidal effects against SCLC cell

lines by raising intracellular levels of Cu, known to be

responsible for ROS generation via Fenton reaction (32,40).

Intriguingly, after treatment with PDTC, the

expression level of ATP7A, a copper export protein responsible for

maintaining copper homeostasis (16,19–21),

significantly decreased in NCI-H196 cells, whereas almost no

alteration was observed in the expression level of CTR1 responsible

for copper uptake (16). Although

the detailed mechanisms underlying the downregulation of the

expression level of ATP7A are need to clarify, these results

provide a new rationale for the clinical use of PDTC since

expression of ATP7A has been reportedly associated with

platinum-drug resistance in various types of solid tumors (17–19).

It is especially noteworthy that ATP7A overexpression plays an

important role in platinum-resistance of NSCLC, and was a negative

prognostic factor of NSCLC patients treated with platinum-based

chemotherapy (20). Furthermore, a

recent study demonstrated that microRNA-495 enhanced the

sensitivity of NSCLC cells to platinum-drug by modulation of ATP7A

expression (21). Although PDTC

has been demonstrated to sensitize different types of cancer cells

by inhibiting transcription activity of NF-κB (12,13),

the effects of PDTC on the expression of copper transporters still

remains unclear. Therefore, our current findings suggest that PDTC

can raise the intracellular level of Cu via downregulation of ATP7A

expression, result in the accumulation of intracellular ROS, and

consequently cause profound cytotoxicity in SCLC cell lines. Based

on the fact that the expression of ATP7A is closely related with

platinum-resistance in various types of solid tumors including lung

cancer (17,19–21,41),

we further hypothesized that PDTC could probably be able to

sensitize SCLC cells to cisplatin. As expected, combination of much

lower dose of cisplatin (5 μM) and non-toxic dose of PDTC (0.1 μM)

synergistically induced a significant cytotoxicity in NCI-H196

cells, the details of the study on the synergistic effects are

current underway.

In conclusion, PDTC-induced cytocidal effects

against SCLC cells were characterized by the S phase arrest

paralleled with suppression of c-myc expression.

Furthermore, the cytotoxicity triggered by PDTC and

CuCl2, alone or in combination, was significantly

abrogated by the addition of BCPS. Importantly, the downregulation

of ATP7A expression was observed for the first time in PDTC-treated

NCI-H196 cells. These results support the plausibility that

increased accumulation of intracellular Cu as a result of ATP7A

inhibition plays an important role in PDTC-mediated cytotoxicity in

SCLC cell lines, although its exact concentrations were not

evaluated in the current study. Given that ATP7A plays a critical

role in the resistance of platinum-drugs (such as cisplatin)

representing the first-line treatment of SCLC, PDTC could be a

promising candidate of adjunct therapeutic reagent for the patients

requiring treatment with platinum-based regimens.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by grants from the

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology and

by the Promotion and Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of

Japan.

References

|

1

|

Chan BA and Coward JI: Chemotherapy

advances in small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 5:S565–S578.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA and De

Ruysscher DK: Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 378:1741–1755.

2011.

|

|

3

|

Jackman DM and Johnson BE: Small-cell lung

cancer. Lancet. 366:1385–1396. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Chinery R, Brockman JA, Peeler MO, Shyr Y,

Beauchamp RD and Coffey RJ: Antioxidants enhance the cytotoxicity

of chemotherapeutic agents in colorectal cancer: a p53-independent

induction of p21WAF1/CIP1 via C/EBPbeta. Nat Med.

3:1233–1241. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Herrmann JL, Beham AW, Sarkiss M, et al:

Bcl-2 suppresses apoptosis resulting from disruption of the

NF-kappa B survival pathway. Exp Cell Res. 237:101–109. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chen SH, Liu SH, Liang YC, Lin JK and

Lin-Shiau SY: Death signaling pathway induced by pyrrolidine

dithiocarbamate-Cu(2+) complex in the cultured rat cortical

astrocytes. Glia. 31:249–261. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Forman HJ, York JL and Fisher AB:

Mechanism for the potentiation of oxygen toxicity by disulfiram. J

Pharmacol Exp Ther. 212:452–455. 1980.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Goldstein BD, Rozen MG, Quintavalla JC and

Amoruso MA: Decrease in mouse lung and liver glutathione peroxidase

activity and potentiation of the lethal effects of ozone and

paraquat by the superoxide dismutase inhibitor

diethyldithiocarbamate. Biochem Pharmacol. 28:27–30. 1979.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Nobel CI, Kimland M, Lind B, Orrenius S

and Slater AF: Dithiocarbamates induce apoptosis in thymocytes by

raising the intracellular level of redox-active copper. J Biol

Chem. 270:26202–26208. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Donadelli M, Dalla Pozza E, Costanzo C, et

al: Increased stability of P21(WAF1/CIP1) mRNA is required for

ROS/ERK-dependent pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell growth inhibition

by pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1763:917–926.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Chen SH, Lin JK, Liang YC, Pan MH, Liu SH

and Lin-Shiau SY: Involvement of activating transcription factors

JNK, NF-kappaB, and AP-1 in apoptosis induced by pyrrolidine

dithiocarbamate/Cu complex. Eur J Pharmacol. 594:9–17. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Morais C, Gobe G, Johnson DW and Healy H:

Inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B transcription activity drives

a synergistic effect of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate and cisplatin

for treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Apoptosis. 15:412–425. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Venkatraman M, Anto RJ, Nair A, Varghese M

and Karunagaran D: Biological and chemical inhibitors of NF-kappaB

sensitize SiHa cells to cisplatin-induced apoptosis. Mol Carcinog.

44:51–59. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Evans WK, Shepherd FA, Feld R, Osoba D,

Dang P and Deboer G: VP-16 and cisplatin as first-line therapy for

small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 3:1471–1477. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sundstrom S, Bremnes RM, Kaasa S, et al:

Cisplatin and etoposide regimen is superior to cyclophosphamide,

epirubicin, and vincristine regimen in small-cell lung cancer:

results from a randomized phase III trial with 5 years’ follow-up.

J Clin Oncol. 20:4665–4672. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Safaei R: Role of copper transporters in

the uptake and efflux of platinum containing drugs. Cancer Lett.

234:34–39. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Samimi G, Safaei R, Katano K, et al:

Increased expression of the copper efflux transporter ATP7A

mediates resistance to cisplatin, carboplatin, and oxaliplatin in

ovarian cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 10:4661–4669. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Safaei R, Katano K, Samimi G, et al:

Cross-resistance to cisplatin in cells with acquired resistance to

copper. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 53:239–246. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Inoue Y, Matsumoto H, Yamada S, et al:

Association of ATP7A expression and in vitro sensitivity to

cisplatin in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett. 1:837–840.

2010.

|

|

20

|

Li ZH, Qiu MZ, Zeng ZL, et al:

Copper-transporting P-type adenosine triphosphatase (ATP7A) is

associated with platinum-resistance in non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC). J Transl Med. 10:212012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Song L, Li Y, Li W, Wu S and Li Z: miR-495

enhances the sensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer cells to

platinum by modulation of copper-transporting P-type adenosine

triphosphatase A (ATP7A). J Cell Biochem. 115:1234–1242. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Imai M, Kikuchi H, Denda T, Ohyama K,

Hirobe C and Toyoda H: Cytotoxic effects of flavonoids against a

human colon cancer derived cell line, COLO 201: a potential natural

anticancer substance. Cancer Lett. 276:74–80. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Yuan B, Ohyama K, Bessho T and Toyoda H:

Contribution of inducible nitric oxide synthase and

cyclooxygenase-2 to apoptosis induction in smooth chorion

trophoblast cells of human fetal membrane tissues. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 341:822–827. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kikuchi H, Yuan B, Yuhara E, Takagi N and

Toyoda H: Involvement of histone H3 phosphorylation through p38

MAPK pathway activation in casticin-induced cytocidal effects

against the human promyelocytic cell line HL-60. Int J Oncol.

43:2046–2056. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kon A, Yuan B, Hanazawa T, et al:

Contribution of membrane progesterone receptor alpha to the

induction of progesterone-mediated apoptosis associated with

mitochondrial membrane disruption and caspase cascade activation in

Jurkat cell lines. Oncol Rep. 30:1965–1970. 2013.

|

|

26

|

Hu XM, Yuan B, Tanaka S, et al:

Involvement of oxidative stress associated with glutathione

depletion and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in

arsenic disulfide-induced differentiation in HL-60 cells. Leuk

Lymphoma. 55:392–404. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Obaya AJ, Mateyak MK and Sedivy JM:

Mysterious liaisons: the relationship between c-Myc and the cell

cycle. Oncogene. 18:2934–2941. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhang P, Li H, Wu ML, et al: c-Myc

downregulation: a critical molecular event in resveratrol-induced

cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of human medulloblastoma cells. J

Neurooncol. 80:123–131. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Payne CM, Bernstein C and Bernstein H:

Apoptosis overview emphasizing the role of oxidative stress, DNA

damage and signal-transduction pathways. Leuk Lymphoma. 19:43–93.

1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Keyse SM and Tyrrell RM: Heme oxygenase is

the major 32-kDa stress protein induced in human skin fibroblasts

by UVA radiation, hydrogen peroxide, and sodium arsenite. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 86:99–103. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Keyse SM and Tyrrell RM: Both near

ultraviolet radiation and the oxidizing agent hydrogen peroxide

induce a 32-kDa stress protein in normal human skin fibroblasts. J

Biol Chem. 262:14821–14825. 1987.

|

|

32

|

Furuta S, Ortiz F, Zhu Sun X, Wu HH, Mason

A and Momand J: Copper uptake is required for pyrrolidine

dithiocarbamate-mediated oxidation and protein level increase of

p53 in cells. Biochem J. 365:639–648. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Oltersdorf T, Elmore SW, Shoemaker AR, et

al: An inhibitor of Bcl-2 family proteins induces regression of

solid tumours. Nature. 435:677–681. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Olejniczak ET, Van Sant C, Anderson MG, et

al: Integrative genomic analysis of small-cell lung carcinoma

reveals correlates of sensitivity to bcl-2 antagonists and uncovers

novel chromosomal gains. Mol Cancer Res. 5:331–339. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Malaguarnera L, Pilastro MR, DiMarco R, et

al: Cell death in human acute myelogenous leukemic cells induced by

pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate. Apoptosis. 8:539–545. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Cheng YC, Lin H, Huang MJ, Chow JM, Lin S

and Liu HE: Downregulation of c-Myc is critical for valproic

acid-induced growth arrest and myeloid differentiation of acute

myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 31:1403–1411. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, et al: Cancer

chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived

from grapes. Science. 275:218–220. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Aragones J, Lopez-Rodriguez C, Corbi A, et

al: Dithiocarbamates trigger differentiation and induction of CD11c

gene through AP-1 in the myeloid lineage. J Biol Chem.

271:10924–10931. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bae KM, Wang H, Jiang G, Chen MG, Lu L and

Xiao L: Protein kinase C epsilon is overexpressed in primary human

non-small cell lung cancers and functionally required for

proliferation of non-small cell lung cancer cells in a

p21/Cip1-dependent manner. Cancer Res. 67:6053–6063. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Lloyd DR and Phillips DH: Oxidative DNA

damage mediated by copper(II), iron(II) and nickel(II) fenton

reactions: evidence for site-specific mechanisms in the formation

of double-strand breaks, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine and putative

intrastrand cross-links. Mutat Res. 424:23–36. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zhang H, Wu JS and Peng F: Potent

anticancer activity of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate-copper complex

against cisplatin-resistant neuroblastoma cells. Anticancer Drugs.

19:125–132. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|