Introduction

In recent years, cytokine research has been at the

forefront of cancer research and cytokine approaches are involved

in the treatment of various carcinomas. Cytokine approaches for

cancer therapy have three potential mechanisms of action. They can

i) directly induce cell death programs in tumor cells, ii) increase

the number or activity of immune effector cells, or iii) increase

the recognition of tumor cells by the immune system (1).

Interferons (IFNs) are one of the most important

cytokines. They are naturally secreted glycoproteins produced by

almost every cell type as a mechanism of host defense in response

to microbial attack (2). The IFN

family includes three different groups. IFNα belongs to the type I

IFN group, and was discovered 50 years ago. It was the first

cytokine to be produced by recombinant DNA technology, and it is

used as an important regulator of cell growth and differentiation,

affecting cellular communication and signal transduction pathways

as well as immunological control (3). More recently, IFNα has been applied

in the treatment of multiple carcinomas including leukemia,

hepatocellular carcinoma, bladder cancer, and osteosarcoma

(4–7).

Breast cancer is a leading cause of cancer-related

death in women worldwide. According to GLOBOCAN 2012, there are

approximately 1.67 million newly diagnosed breast cancer patients

every year (8). In China, breast

cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer, and the number of

breast cancer patients has been increasing annually (9). Surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy,

endocrinotherapy and molecular targeting therapy are the major

treatment modalities for breast cancer. However, challenges remain

in the treatment of breast cancer, and novel therapeutic approaches

are urgently needed.

Although the use of IFN in clinical practice is

widely recommended, its antineoplastic activity and clinical

efficacy for breast cancer is still unclear and controversial

(10,11). In this study, an NEB Ph.D.-12

peptide library was employed to select a short peptide that

specifically binds to the cell membrane of MCF-7 cells, and a

high-affinity IFNα-MCF-7 fusion molecule IMBP was constructed. Our

aim was to investigate whether this reconstructed cytokine had

enhanced cell growth inhibition activity compared to the wild-type

IFNα.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human breast cancer cell line MCF-7, lung cancer

cell line A549 and prostate cancer cell line PC-3 were kept in our

lab. Human embryonic kidney 293T cell line was used for lentiviral

packaging. All cell lines were routinely cultivated in Dulbecco's

modified eagle's medium (DMEM, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) with

10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) at 37°C in a humidified

atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Phage display library screening of breast

cancer binding peptides

Phage display library (Ph.D.-12 library, #E8110S,

New england Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) was employed to screen a

short 12-peptide that specifically binds to MCF-7 breast cancer

cells (12,13). Briefly, 1×1011 phage in

1 ml DMEM medium was incubated with 1×106 MCF-7 cells at

room temperature (RT) for 1 h to develop phage-cell complexes.

After binding, cells were washed 5 times with 5 ml TBST [TBS (10

mmol/l Tris pH 7.5, 150 mmol/l NaCl) containing 0.1% Tween-20] to

remove the unbound phages. Cells were collected by centrifuging at

3200 × g. The surface-bound phages were eluted in 1 ml elution

buffer [0.2 N Glycine-HCl (pH 2.2), 1 mg/ml BSA] for 20 min and was

neutralized by 150 μl 1 N Tris-HCl, pH 9.0. The eluted

phages were reproduced by infecting E. coli ER2738 and

purified using polyethylene glycol (PEG)-8000/NaCl solution (20%

PEG-8000 and 2.5 N NaCl).

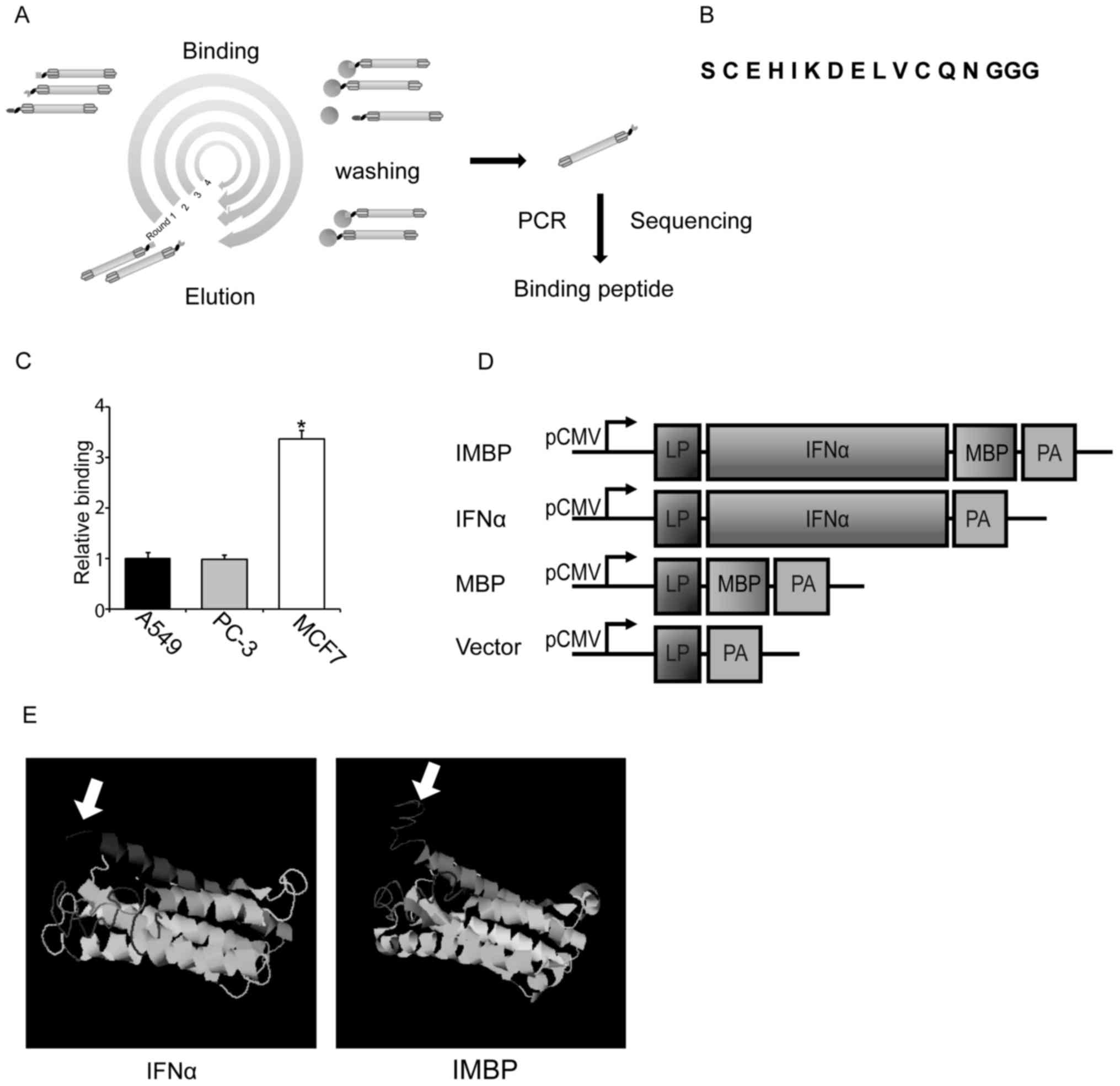

After 4 rounds of surface panning, the DNA sequences

of MCF-7-binding peptide (MBP) were amplified by PCR (Fig. 1A). Primers used for PCR

amplification were as follows: 5′-CTTTAGTGGTACCTTTCTATTCTCGAGTCT-3′ (forward primer

with Xho I) and 5′-CTTTCAACAGTTTCGTCTAGAACCTCCACC-3′ (reverse

primer with XbaI). The PCR production was purified from 3%

agrose gel and cloned into pJet vector using CloneJET PCR Cloning

kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for sequencing and

constructing the engineered IFNα molecules.

Phage-ELISA assay

Phage-ELISA was carried out to determine the binding

affinity of the isolated MBP. Approximately 2×104 MCF-7

cells were collected into a 96-well V-bottom tissue culture plate

and incubated with blocking buffer (5% BSA/PBS, Sigma, Shanghai,

China) at 37°C for 1 h. For comparison, A549 lung cancer and PC-3

prostate cancer cells were used as negative controls. Cells were

pelleted by centrifuging at 3,200 × g and resuspended in 100

μl PBS buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Beijing, China)

containing 1×109 phage particles. After incubated at RT

for 1 h, cells were pelleted and washed with PBST for 5×5 min. For

quantitation, cells were incubated with 100 μl PBS buffer

containing HRP conjugated anti-M13 monoclonal antibody (1:5,000, GE

Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) at 37°C for 45 min. Cells were

centrifuged and washed by PBST for 5×5 min. Then 100 μl of

TMB solution (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) was added to each

well and the plate was kept in the dark for 15 min until blue color

was developed. Reaction was stopped by adding 50 μl 1 N

sulfuric acid. The absorbance of 450 nm and 630 nm were measured by

microplate reader (Bioteck, Beijing, China). Final optical density

(OD) was designated as

OD450-OD630-ODblank.

Recombinant plasmid construction

After the phage library screening and sequencing,

one of the MBP sequence was selected for the following cell

studies. We ligated MBP to the C-terminus of IFNα to construct an

engineered synthetic IFNα fusion protein. The fusion protein was

generated by ligating the MBP sequence into IFNα vector at the

XhoI/XbaI restriction sites and was designated as

IMBP. The wild-type IFNα expression plasmid was prepared as

previous described (14,15) and kept in our laboratory. The

vector containing the isolated MBP sequence and the empty

lentivirus vector were constructed in parallel and used as control

groups. All plasmid constructs were confirmed by DNA

sequencing.

The putative structure of the IMBP

The putative structure of the synthetic IMBP was

predicted using online I-TASSER server (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu).

Lentivirus production

293T cells were seeded into a 6-well plate at a

proper density 24 h pre-transfection. Lentiviruses were packaged by

the co-transfection of the plasmids constructed above and

pSPAX2/pMD2.G packing vectors (System Biosciences, Mountain View,

CA, USA) using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Thermo Fisher

Scientific). The viral supernatants were collected at 24 and 48 h

post-transfection and used for cell transfection as previously

described (16,17).

Infection of recombinant lentivirus

Approximately 2×105 MCF-7 cells were

plated into a 6-well plate 24 h pre-transfection. Cells were

infected with lentiviruses carrying MBP, IFNα, IMBP and empty

vector DNA in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma).

After two rounds of infection with lentiviruses at 37°C for 24 h,

the tissue culture medium was replaced with fresh complete medium.

Three days after viral infection, the stable MCF-7 cells were

selected by puromycin and used for the following cell

experiments.

Detection of the secreted IMBP fusion

protein

On day 5 post-transduction, 100 μl

supernatant of MCF-7 cells was collected and the secreted IFNα and

IMBP fusion protein were quantitated with IFNα assay kit according

to the manufacture's instruction (Cusabio, Hubei, China).

Western blotting

Protein were extracted with RIPA buffer (KeyGEN

Biotech, Jiangsu, China) supplemented with cocktail protease

inhibitor (Roche, Shanghai, China) and quantified with BCA protein

assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Jiangsu, China). Whole cell

lysates were resolved on 5–10% or 5–12% SDS polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). To detect the secreted IFNα and IMBP

proteins in cell supernatants, on day 5 post-transduction, 100

μl MCF-7 cell supernatant was collected and condensed to 20

μl in a vacuum-freeze dryer (Boyikang, Beijing, China).

Solutions were resolved on Mini-PROTEIN TGX gradient gel (Bio-Rad,

Beijing, China). Proteins were transferred to 0.45 μm PVDF

membranes (Roche) and immunoblotted at 4°C overnight or at RT for 1

h with the following antibodies: IFNα (1:1,000, Abcam, Shanghai,

China), STAT1 (phospho Y701, 1:1,000, Abcam), Cleaved CASP-9

(1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, Beijing, China), p53 (1:1,500,

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), p21 (1:500, Santa

Cruz Biotechnology), CDK2 (1:1500, Cell Signaling Technology),

Cyclin A (1:1,500, Abcam) and β-actin (1:3,000, Santa Cruz

Biotechnology). Membranes were incubated with horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:3,000, ZSGB-BIO,

Beijing, China) at 37°C for 1 h before chemiluminescence reading.

Protein expression levels were determined semi-quantitatively by

densitometric analysis with the Quantity One software (Bio-Rad).

Western blotting was performed in triplicate, and data showed a

representative finding of these triplicate analyses.

Cell binding assay of IMBP

The binding affinity of the engineered hybrid

molecule to the MCF-7 cell membrane was measured by FACS. MCF-7

cells were collected and stained with Trypan blue to make sure that

viable cells were more than ninety percent. Approximately

1×106 normal MCF-7 cells were incubated with equal

amount of the secreted IFNα or IMBP at 37°C for 1 h. After washed

with PBS, cells were incubated with FITC-conjugated IFNα antibody

(PBL, Piscataway, NJ, USA). The FITC-conjugated mouse IgG (Abcam)

was used as the isotype control. Cells were analyzed using BD LSRII

Fortesa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and FlowJo software

(FlowJo, OR, Ashland, USA) to calculate the fluorescence intensity

(14,15).

Cell viability assay

On day 7 post-transfection, approximately

5×103 viable stable MCF-7 cells transduced by lentivirus

carrying IMBP, IFNα, MBP and empty vector DNA were seeded into a

96-well plate 24 h before cell viability assay. Then, cell growth

was analyzed by WST-1 Cell Proliferation Reagent (Roche). According

to the manufacturer's instructions, 20 μl WST-1 reagent was

added to 200 μl cell culture medium and incubated at 37°C in

the dark for 2 h. The absorbances of 450 and 630 nm were measured

with microplate reader (Bioteck). Final OD was designated as

OD450-OD630-ODblank.

Cell cycle assay

On day 7 post-transfection, 1×106 stable

MCF-7 cells were collected and washed by cold PBS. Cells were

resuspended in 1 ml fixation solution (300 μl PBS and 700

μl ethanol). After incubation at 4°C for 4 h, cells were

centrifuged and the fixation solution was removed. After washed

twice with PBS, cells were pelleted, stained with 0.5 ml propidium

iodide (PI, Sigma) staining solution [50 μg/ml PI, 20

μg/ml RNase A (Takara, Liaoning, China) and 0.2% Triton

X-100 (Sigma)], and incubated in the dark at 37°C for 10 min. Cell

suspensions were filtered with a 400-mesh sieve. Cell cycle was

analyzed by BD LSRII Fortesa flow cytometer.

Flow cytometry for cell apoptosis

Annexin V-FITC and PI double staining flow cytometry

analyses were used for cell apoptosis assay. Approximately

1×106 stable MCF-7 cells were collected and washed three

times with cold PBS and binding buffer. Then cells were stained

with Annexin V-FITC and PI (Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection kit,

BD Bioscience) for apoptosis detection. Briefly, MCF-7 cells were

first resuspended in 1 ml binding buffer. Then, 5 μl of

Annexin V-FITC was added to the tubes, and cells were incubated for

10 min at RT followed by the addition of 5 μl PI. After 15

min incubation in PI buffer at RT, cells were immediately analyzed

with a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). The cells in the different

portions represented the different cell states as follows: the

late-apoptotic cells were present in the upper right portion, the

viable cells were present in the lower left portion, and the early

apoptotic were cells present in the lower right portion.

Treatment with chemotherapeutic drug

doxorubicin

The anticancer drug doxorubicin (DOX, Sigma) was

dissolved in water. We harvested 12 ml of cell supernatant

containing the secreted interferons from the stable MCF-7 cells

transduced by lentivirus carrying IMBP, IFNα, MBP and empty vector.

The cell supernatant was centrifuged at 3,500 × g for 5 min to

remove cell debris. Then the supernatant was successively passed

through two centrifugal filter units with MW cut-off 30 and 10 kDa

(Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) to remove large and small molecules.

The interceptions were dissolved in 6 ml DMEM complete medium and

kept in 4°C. Normal MCF-7 cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a

density of 3×105 cells/well. After 24 h, cell medium was

changed to the interception-DMEM supplemented with 0.1 μg/ml

DOX. MCF-7 cells were treated with this therapeutic medium for 3

days, with the medium changed every day. After that, cells were

harvested and applied for the next step of cell viability assay or

molecule detection.

Real-time PCR

Total cellular RNA was isolated using an Eastep

Super total RNA isolation kit (Promega, Beijing, China).

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 800 ng of total RNA using

Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche). Real-time PCR

was performed using an aliquot of first-strand cDNA as a template

in a 20 μl reaction system containing 10 μl 2X SYBR

premixed buffer (Roche), 2 μl forward and reverse primers.

The primers were as follows: IFIT1 (interferon induced protein with

tetratricopeptide repeats) sense 5′-TCTCAGAGGAGCCTGGCTAA-3′, IFIT1

antisense 5′-CCAGACTATCCTTGACCTGATGA-3′; MX1 (MX dynamin-like

GTPase 1) sense: 5′-CTTTCCAGTCCAGCTCGGCA-3′, MX1 antisense:

5′-AGCTGCTGGCCGTACGTCTG-3′); STAT1 sense:

5′-GGCACCAGAACGAATGAGGG-3′, STAT1 antisense:

5′-CCATCGTGCACATGGTGGAG-3′ (18);

IFITM1 (interferon-induced transmembrane protein 1) sense:

5′-ACAGGAAGATGGTTGGCGAC-3′, IFITM1 antisense:

5′-ATGGTAGACTGTCACAGAGC-3′; β-actin sense:

5′-TCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTACGA-3′, β-actin antisense:

5′-CAGCGGAACCGCTCATTGCCAA TGG-3′ (19). The PCR amplification process was

one cycle at 95°C 10 min, 40 cycles at 95°C for 10 sec and 60°C for

30 sec (ABI StepOnePlus, Beijing, China).

Statistical analysis

All data and results were calculated from at least

three replicate measurements and presented as means ± SD. The

significance was determined by SPSS 20.0 (IBM). Student's t-test

was used to compare statistical differences for variables among

treatment groups. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Construction of the IFNα/MCF-7-binding

peptide fusion protein

In order to enhance the antitumor activity of IFNα

in breast cancer therapy, we used a NEB Ph.D.-12 peptide library to

select a short peptide with 12 amino acids that specifically binds

to the cell membrane of MCF-7 cells. Our aim is to add a short,

high-affinity peptide to the C-terminus of IFNα and construct an

IFNα-MCF-7 fusion molecule (IMBP), which may facilitate the binding

of IFNα to the MCF-7 cell membranes and enhance the cell growth

inhibition activity of IFNα.

According to the manual of NEB Ph.D.-12 peptide

library, MCF-7 cells were incubated with 1×1011 phage

particles in DMEM tissue culture medium. The unbounded phage

particles were stripped off by stripping buffer. The bound phages

on the cell membrane were eluted and recovered for the second round

of screening. After four rounds of screening, the phages

specifically binding to MCF-7 cells were enriched and identified

(Fig. 1A). After cloning and

sequencing, one sort of phage encodes short peptide with the

sequence of 'C E H I K D E L V C Q N' was selected for further cell

studies (Fig. 1B). Using

phage-ELISA, we showed that this phage displayed short peptide was

able to bind preferentially to MCF-7 cells compared to A549 lung

cancer and PC-3 prostate cancer cells (Fig. 1C).

In order to examine the role of this short peptide

and compare the antitumor activity of wild-type IFNα and IMBP, we

linked the short peptide to the C-terminus of IFNα and the IMBP

fusion molecule was synthesized (Fig.

1D). Then we used software on the website (http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu) to predict

the protein structure of the synthetic IMBP. The structure of

wild-type IFNα and the putative structure of IMBP is illustrated in

Fig. 1E. Arrow indicates the short

peptide fused into wild-type IFNα.

Detection of the secreted IFNα and IMBP

fusion protein

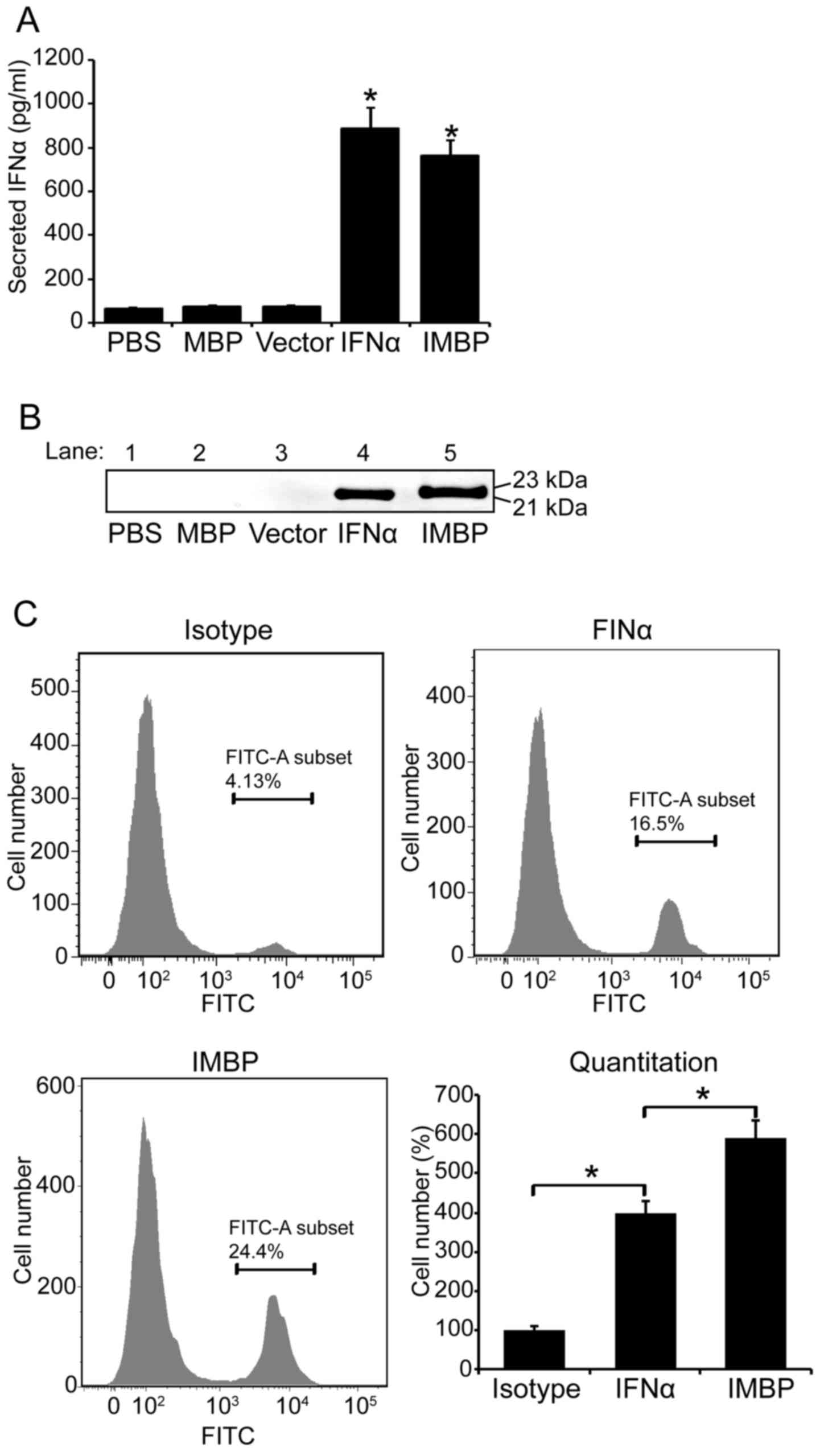

We used 293T cells to produce lentivirus carring the

DNA sequences of IMBP, wild-type IFNα, MBP and empty vector. Then,

MCF-7 cells were transducted by lentiviruses and the stable cells

were selected with puromycin. On day 5 post-transduction, 100

μl supernatant of MCF-7 cells was collected and the secreted

IFNα and IMBP fusion protein were quantitated with IFNα assay kit.

Based on the result of IFNα ELISA, the concentration of secreted

wild-type IFNα in MCF-7 supernatant was 885 pg/ml and that of the

IMPB fusion molecule was 763 pg/ml (Fig. 2A). We further used western blotting

to confirm the secretion of wild-type IFNα and IMPB fusion

molecule. The blots are shown in Fig.

2B.

Since the phage particles bind to MCF-7 cell

membrane specifically, we used FACS to further examine whether the

IMBP fusion protein binds to MCF-7 cell surface easier than the

wild-type IFNα. Therefore, FITC conjugated-IFNα antibody was used

in FACS assay and the binding affinity of the two proteins was

quantitatively evaluated according to the fluorescence intensity in

flow cytometry (Fig. 2C).

Quantitative analysis result showed that the binding affinity of

the IMBP fusion protein was 1.5-fold increase compared to the

wild-type IFNα (P<0.05), and the binding ability of both the

wild-type IFNα and the IMBP fusion protein was significantly higher

than the isotype control (Fig. 2C,

P<0.05).

Synthetic IMBP fusion protein inhibits

cell growth of MCF-7 cells

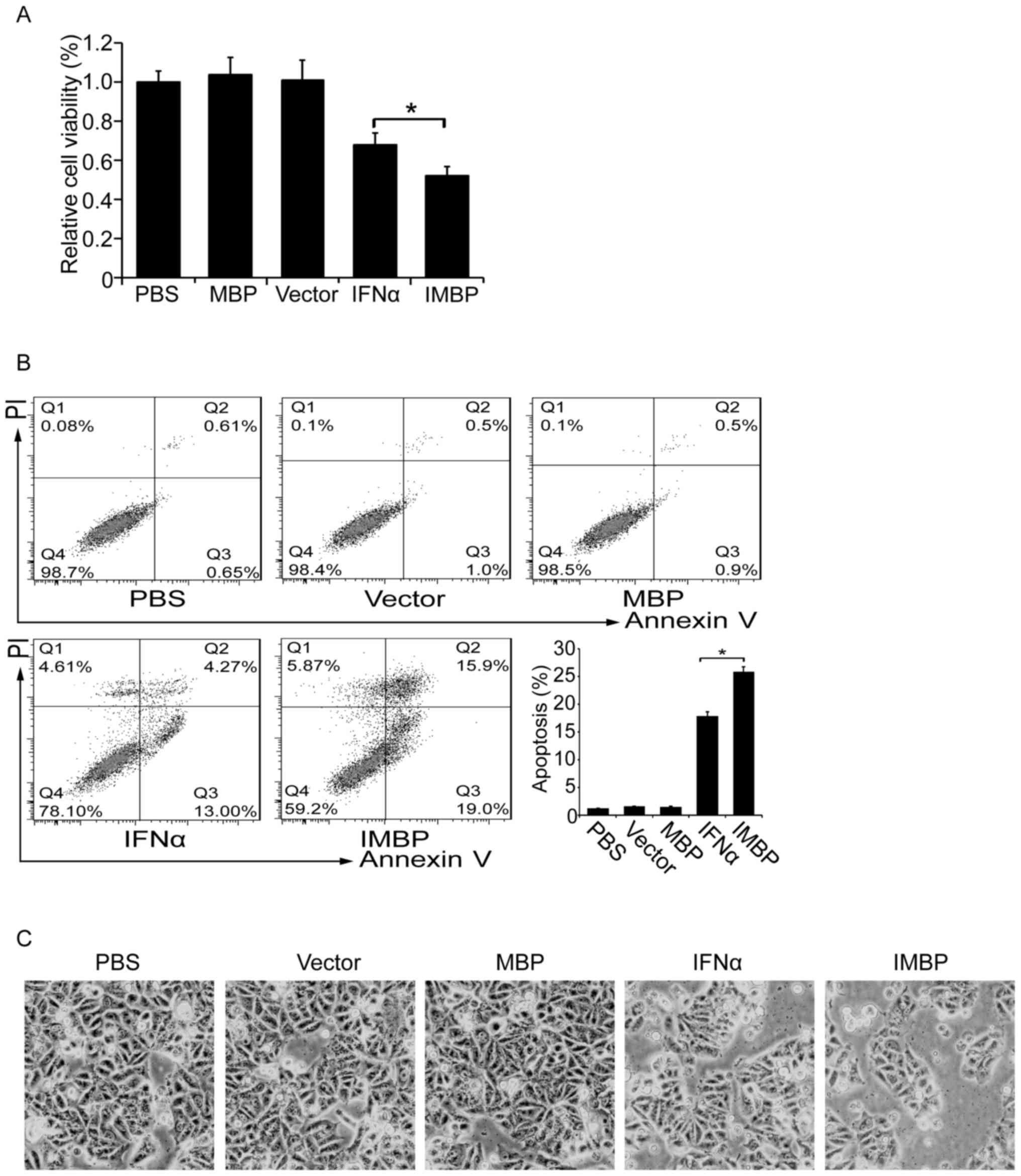

We compared the cell growth inhibition effect

between the IMBP and the wild-type IFNα. MCF-7 breast cancer cells

were transfected with lentiviruses carrying IMBP, IFNα, MBP and

empty vector, respectively. Cell proliferation was determined by

WST-1 assay. We found that although both the secreted IFNα and IMBP

inhibited the growth of MCF-7 cells, IMBP was superior to IFNα

(Fig. 3A, P<0.05).

Then we examined cell apoptosis of the stable

transfected MCF-7 cells with flow cytometry. As was shown in

Fig. 3B, we found that the

transfection of both IFNα and IMBP induced an increased apoptosis

ratio, but the IMBP group showed a significantly higher apoptosis

ratio than the IFNα group (26 vs. 18%, P<0.05). The cell

morphology also showed a similar result (Fig. 3C).

IMBP potentiates the therapeutic efficacy

of doxorubicin-based chemotherapy

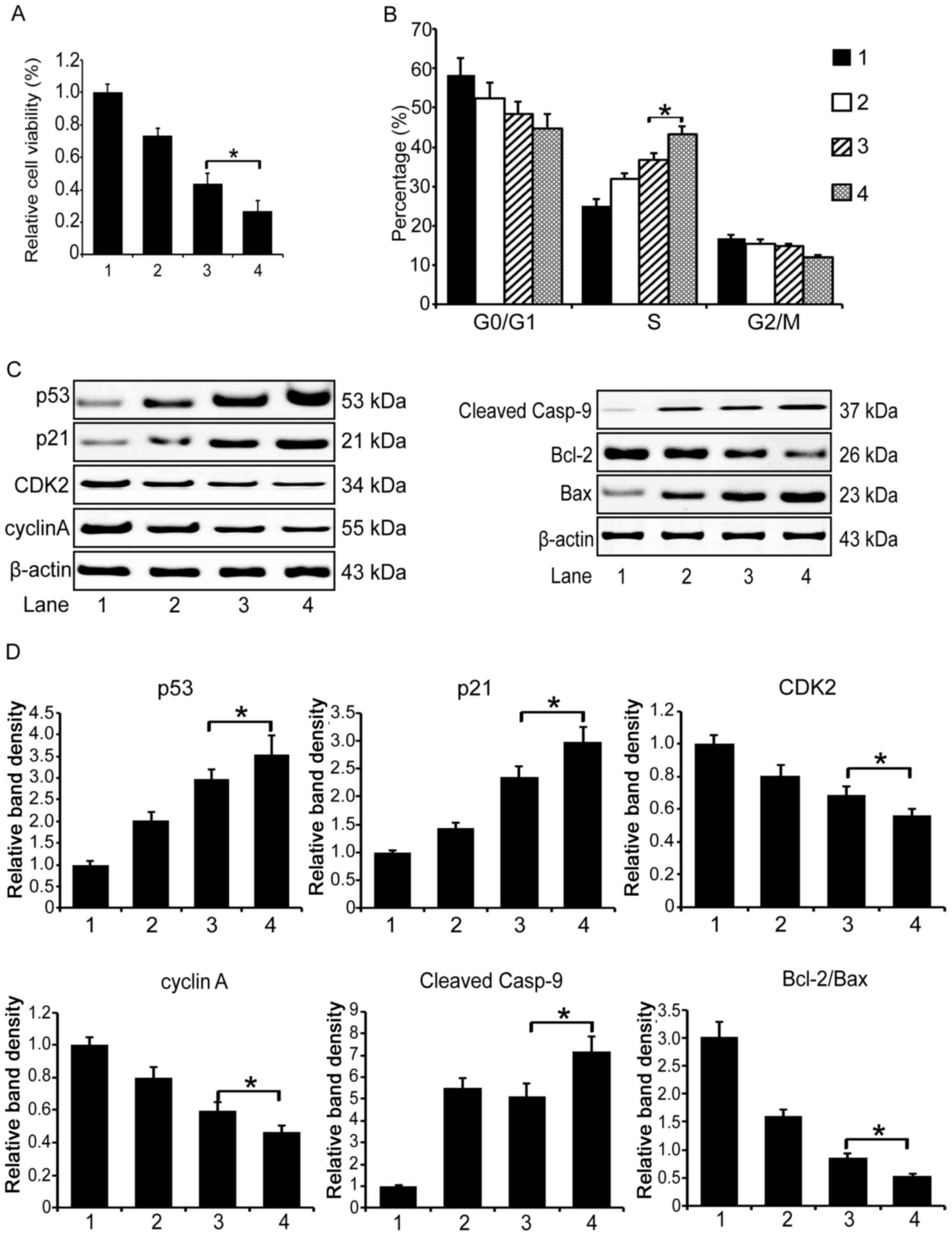

Since doxorubicin is one of widely used

anthracyclines to treat breast cancer, we examined the synergistic

effect on cell killing by the combined use of DOX and IMBP fusion

molecule. First, using WST-1 cell proliferation assay, we tested a

serial working concentration of DOX including 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2,

0.5 and 1.0 μg/ml for the cell growth inhibition of MCF-7

cells. We selected a relative low concentration of 0.1 μg/ml

of DOX with a cell growth inhibition ratio approximately 25% for

the chemotherapy (data not shown). Then, we investigated the cell

killing ability of the co-administration of DOX/IFNα or DOX/IMBP.

The WST-1 assay result showed that cell proliferation in both the

DOX/IFNα and DOX/IMBP treatment groups was apparently inhibited

compared to the PBS control group and the DOX group. Of note, cell

killing ability of the co-administration of DOX and IMBP was

superior to the co-administration of DOX and IFNα (Fig. 4A, 48 vs. 32%, P<0.05).

Then we examined the cell cycle distribution in the

treated MCF-7 cells with flow cytometry. We found that the

co-administration apparently induced an S phase cell cycle arrest,

and the DOX/IMBP treatment group showed a more obvious arrest

effect than the DOX/IFNα group (Fig.

4B, 43 vs. 37%, P<0.05).

To unveil the underlying molecular mechanism that

explains the enhanced therapeutic efficacy of the combined use of

DOX and IMBP in chemotherapy, we first examined the expression of

the cell cycle pathway related genes by western blotting. We found

that the expression of p53 and p21 in the DOX/IMBP chemotherapy

group was dramatically up-regulated compared to the DOX/IFNα group;

the expression of CDK2 and cyclin A was dramatically down regulated

(Fig. 4C left panel and D,

P<0.05). We then examined the expression of the cell apoptosis

pathway-related genes and found that the caspase 9 and Bcl-2/Bax

apoptosis pathways were activated (Fig. 4C right panel and D, P<0.05).

IMBP fusion molecule activates the STAT1

pathway

To further delineate the mechanism of the enhanced

activity of the combination chemotherapy, we used real-time PCR to

examine the expression of the interferon pathway genes in the

treated MCF-7 cells. The quantitation result showed that both the

DOX/IMBP and DOX/IFNα co-administration activate several inducible

genes of the STAT1 pathway, including STAT1, IFIT1, IFITM1, and

MX1. However, DOX/IMBP group showed a stronger activation effect

than the DOX/IFNα group (Fig. 5A).

The western blot analysis result also showed an activation of the

phosphorylated STAT1 (Y701, Fig.

5B).

Discussion

Anthracyclines, one type of anticancer therapy, are

commonly used to treat both early and metastatic breast cancer;

however, their toxicity, especially cardiac toxicity, is high

(20,21). Additionally, frequent use of single

therapeutic agent may result in chemoresistance, which is a major

obstacle to the successful treatment of breast cancer. To minimize

the toxicity of DOX and maximize the therapeutic efficiency of DOX,

a combination therapeutic strategy is important.

The functions of IFNs are represented by three major

biological activities, antiviral activity, antitumor activity and

immunoregulatory activity (22).

Although IFNα is widely used in the treatment of various types of

cancer, its antineoplastic potency for breast cancer is low.

Therefore, improvements in this cytokine are valuable and further

investigation is still needed.

In our previous study, using a cDNA in-frame library

screening approach, we identified a short peptide derived from

placental growth factor-2 (PLGF-2). We demonstrated that fusing

this short peptide to IFNα and IFNγ induced greater activity than

the wild-type counterparts in inhibiting of tumor cell growth,

invasion and colony formation (14,15).

In this study, using a Ph.D.-12 peptide library, we selected a

short peptide that specifically binds to the cell membrane of MCF-7

cells, and we synthesized a high-affinity IFNα-MCF-7 fusion

molecule (IMBP). Using lentiviral DNA delivery system, we obtained

a stable MCF-7 breast cancer cell line that secretes IMBP. Compared

with wild-type IFNα, the IMBP fusion molecule demonstrated higher

antitumor activity potency in the inhibition of cell growth,

promotion of cell cycle arrest and induction of cell apoptosis.

Recently, using the same approach, we also identified a short

peptide that specifically binds to Jurkat T lymphocyte leukemia

cells (JBP). We demonstrated that a JBP and IFNα fusion protein

(IFNP) also had significantly better antitumor activity than

wild-type IFNα (unpublished data). Through this series study, we

evaluated the value of engineering an IFNα fusion molecule, which

may serve as a novel antitumor agent in cancer treatment.

IFNs bind to receptors on the cell surface, activate

specific signaling pathways and exert antitumor actions (23). Unfortunately, we still do not know

the function of how this Ph.D.-12 peptide binds to the cell

membrane. According to the result of 'Blastp' on the NCBI website,

this 12-peptide is not homologous to any existing protein

sequences. We speculate that it may bind to some unknown

receptor(s) or biomacromolecule(s) on the surface of the cell

membrane. Using a cell binding assay, we demonstrated that MBP

promoted the adherence affinity of IFNα to its receptor (Fig. 2C), which is probably why we

detected a lower level of free IMBP in the cell supernatant

(Fig. 2A). We speculate that

because more IMBP molecules adhere to the cell surface of MCF-7

cells than IFNα, the IMBP possesses a higher tumor cell killing

ability than wild-type IFNα.

The STAT pathway plays a critical role in the

anti-infection role of IFNs (24–27).

When binding to its receptor on the cell surface, IFNα initiates

the phosphorylation of TYK2 and JAK1 kinases, which is followed by

the activation of STAT family transcription factors (28,29).

Several IFN inducible genes can be co-activated in the STAT

pathway, including IFIT1, IFIT3, MX1, IFITM1, OAS1

(2′–5′-oligoadenylate synthetase 1), PARP9 and PARP12

[poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase family] (30). It was reported that IFIT3 promotes

IFNα adjuvant therapeutic effects by strengthening IFNα effector

signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma patients (31); IFNγ inhibits the growth of human

liver cancer cells through activating IFITM1, which enhances the

transcriptional activity of p53 and stabilizes the p53 protein by

inhibiting p53 phosphorylation on Thr55 (19).

The JAK-STAT signaling pathway also plays an

important role in doxorubicin-based breast cancer chemotherapy

(32). It was demonstrated that

the combined use of doxorubicin and IFNs may have a significant

synergistic effect. Thomas et al showed that doxorubicin

potentiates STAT1 activation in response to IFNγ, and the

combination of doxorubicin and IFNγ enhances apoptosis in breast

cancer cells (33). Hannesdóttir

et al reported that STAT1 is crucial to the susceptibility

of breast cancer cells to chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g.,

doxorubicin) by contributing to the induction of a productive

antitumor immune response, which is based on IFNγ-producing T cells

(34). In this study, we found

that a combination of low dose DOX antitumor drug (0.1

μg/ml) and endogenous secretory IFNα had an advantage over

the single use of either DOX or IFNα in inhibiting breast cancer

cell growth. Of note, we found that low dose DOX combined with

synthetic IMBP fusion protein had a significantly better

therapeutic effect than the DOX/IFNα combination. When we examined

the molecular mechanism of this enhanced antitumor activity, we

observed that the DOX/IMBP combination activated cell cycle arrest

and cell apoptosis pathway genes more efficiently than the DOX/IFNα

combination (Fig. 4), which was

also correlated with the activation of STAT1 pathway target genes

(Fig. 5).

In summary, by using a phage library screening, we

have identified a short peptide that specifically binds to MCF-7

breast cancer cells. Fusion of this short peptide to IFNα

significantly enhanced the antitumor activity. The combined use of

DOX and IMBP fusion protein potentiated the effectiveness of

chemotherapy. Since using lentivirus to deliver molecules into

cells is hard to apply in clinical gene therapy, construction of an

in vitro expression and purification system to produce

purified IMBP recombinant protein is needed in our further study.

We consider this type of purified IMBP molecule may have good

clinical application prospect and the co-administration of DOX and

IMBP provides new insight into breast cancer treatment.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the

National Science Foundation of China (81302380, to D.-H.Y.) and

Grant from the Health and Family Planning Commission in Jilin

Province of China (2016Q035, to L.Z.).

References

|

1

|

Roychowdhury S and Caligiuri MA: Cytokine

therapy for cancer: Antigen presentation. Cancer Treat Res.

123:249–266. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kotredes KP and Gamero AM: Interferons as

inducers of apoptosis in malignant cells. J Interferon Cytokine

Res. 33:162–170. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gutterman JU: Cytokine therapeutics:

Lessons from interferon alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

91:1198–1205. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lamm D, Brausi M, O'Donnell MA and Witjes

JA: Interferon alfa in the treatment paradigm for

non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol. 32:e21–e30. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Whelan J, Patterson D, Perisoglou M,

Bielack S, Marina N, Smeland S and Bernstein M: The role of

interferons in the treatment of osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer.

54:350–354. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Wang L, Jia D, Duan F, Sun Z, Liu X, Zhou

L, Sun L, Ren S, Ruan Y and Gu J: Combined anti-tumor effects of

IFN-α and sorafenib on hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in

vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 422:687–692. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Simonsson B, Hjorth-Hansen H, Bjerrum OW

and Porkka K: Interferon alpha for treatment of chronic myeloid

leukemia. Curr Drug Targets. 12:420–428. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser

S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D and Bray F: Cancer

incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major

patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 136:e359–e386. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Fan L, Strasser-Weippl K, Li JJ, St Louis

J, Finkelstein DM, Yu KD, Chen WQ, Shao ZM and Goss PE: Breast

cancer in China. Lancet Oncol. 15:e279–e289. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ramos MC, Mardegan MC, Tirone NR, Michelin

MA and Murta EF: The clinical use of type 1 interferon in

gynecology. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 31:145–150. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang BX, Rahbar R and Fish EN: Interferon:

Current status and future prospects in cancer therapy. J Interferon

Cytokine Res. 31:545–552. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li X and Mao C: Using phage as a platform

to select cancer cell-targeting peptides. Methods Mol Biol.

1108:57–68. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Cao B, Yang M and Mao C: Phage as a

genetically modifiable supramacromolecule in chemistry, materials

and medicine. Acc Chem Res. 49:1111–1120. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yin H, Chen N, Guo R, Wang H, Li W, Wang

G, Cui J, Jin H and Hu JF: Antitumor potential of a synthetic

interferon-alpha/PLGF-2 positive charge peptide hybrid molecule in

pancreatic cancer cells. Sci Rep. 5:169752015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Liu Y, Chen N, Yin H, Zhang L, Li W, Wang

G, Cui J, Yang B and Hu JF: A placental growth factor-positively

charged peptide potentiates the antitumor activity of

interferon-gamma in human brain glioblastoma U87 cells. Am J Cancer

Res. 6:214–225. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sun J, Li W, Sun Y, Yu D, Wen X, Wang H,

Cui J, Wang G, Hoffman AR and Hu JF: A novel antisense long

noncoding RNA within the IGF1R gene locus is imprinted in

hematopoietic malignancies. Nucleic Acids Res. 42:9588–9601. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang H, Li W, Guo R, Sun J, Cui J, Wang G,

Hoffman AR and Hu JF: An intragenic long noncoding RNA interacts

epigenetically with the RUNX1 promoter and enhancer chromatin DNA

in hematopoietic malignancies. Int J Cancer. 135:2783–2794. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Choi HJ, Lui A, Ogony J, Jan R, Sims PJ

and Lewis-Wambi J: Targeting interferon response genes sensitizes

aromatase inhibitor resistant breast cancer cells to

estrogen-induced cell death. Breast Cancer Res. 17:62015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yang G, Xu Y, Chen X and Hu G: IFITM1

plays an essential role in the antiproliferative action of

interferon-gamma. Oncogene. 26:594–603. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Khasraw M, Bell R and Dang C: Epirubicin:

Is it like doxorubicin in breast cancer? A clinical review Breast.

21:142–149. 2012.

|

|

21

|

Damiani RM, Moura DJ, Viau CM, Caceres RA,

Henriques JA and Saffi J: Pathways of cardiac toxicity: Comparison

between chemotherapeutic drugs doxorubicin and mitoxantrone. Arch

Toxicol. 90:2063–2076. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Chelbi-Alix MK and Wietzerbin J:

Interferon, a growing cytokine family: 50 years of interferon

research. Biochimie. 89:713–718. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Parker BS, Rautela J and Hertzog PJ:

Antitumour actions of interferons: Implications for cancer therapy.

Nat Rev Cancer. 16:131–144. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Szelag M, Piaszyk-Borychowska A,

Plens-Galaska M, Wesoly J and Bluyssen HA: Targeted inhibition of

STATs and IRFs as a potential treatment strategy in cardiovascular

disease. Oncotarget. 7:48788–48812. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Merches K, Khairnar V, Knuschke T,

Shaabani N, Honke N, Duhan V, Recher M, Navarini AA, Hardt C,

Häussinger D, et al: Virus-induced type I interferon deteriorates

control of systemic pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Cell Physiol

Biochem. 36:2379–2392. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Heim MH and Thimme R: Innate and adaptive

immune responses in HCV infections. J Hepatol. 61(Suppl 1):

S14–S25. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhu Y, Jia H, Chen J, Cui G, Gao H, Wei Y,

Lu C, Wang L, Uede T and Diao H: Decreased osteopontin expression

as a reliable prognostic indicator of improvement in pulmonary

tuberculosis: impact of the level of interferon-gamma-inducible

protein 10. Cell Physiol Biochem. 37:1983–1996. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhao LJ, He SF, Liu Y, Zhao P, Bian ZQ and

Qi ZT: Inhibition of STAT pathway impairs anti-hepatitis C virus

effect of interferon alpha. Cell Physiol Biochem. 40:77–90. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Takaoka A and Yanai H: Interferon

signalling network in innate defence. Cell Microbiol. 8:907–922.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Legrier ME, Bièche I, Gaston J, Beurdeley

A, Yvonnet V, Déas O, Thuleau A, Château-Joubert S, Servely JL,

Vacher S, et al: Activation of IFN/STAT1 signalling predicts

response to chemotherapy in oestrogen receptor-negative breast

cancer. Br J Cancer. 114:177–187. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

31

|

Yang Y, Zhou Y, Hou J, Bai C, Li Z, Fan J,

Ng IOL, Zhou W, Sun H, Dong Q, et al: Hepatic IFIT3 predicts

interferon-α therapeutic response in patients of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Hepatology. Mar 13–2017.Epub ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lee SC, Xu X, Lim YW, Iau P, Sukri N, Lim

SE, Yap HL, Yeo WL, Tan P, Tan SH, et al: Chemotherapy-induced

tumor gene expression changes in human breast cancers.

Pharmacogenet Genomics. 19:181–192. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Thomas M, Finnegan CE, Rogers KM, Purcell

JW, Trimble A, Johnston PG and Boland MP: STAT1: A modulator of

chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 64:8357–8364. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Hannesdóttir L, Tymoszuk P, Parajuli N,

Wasmer MH, Philipp S, Daschil N, Datta S, Koller JB, Tripp CH,

Stoitzner P, et al: Lapatinib and doxorubicin enhance the

Stat1-dependent antitumor immune response. Eur J Immunol.

43:2718–2729. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|