Introduction

Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma (NA) is a rare,

non-encapsulated and highly-vascularized benign tumor that

primarily affects adolescent males (1,2). Extremely

few studies have described NA in elderly individuals; in our

previous report of 162 cases from 1995 to 2012, all patients were

male subjects ranging in age from 8–41 years (mean, 17.5 years)

(3). Although NA is a benign neoplasm

histopathologically, it has a propensity for locally destructive

growth with bone erosion, which can lead to life threatening

complications, such as fatal epistaxis, and other complications,

including facial swelling, proptosis, cranial neuropathy, and

intraoperative massive hemorrhage (1,4). In the

majority of cases, patients present with symptoms of a painless,

unilateral nasal obstruction and epistaxis (4). Currently, surgery is the standard

treatment for NA (5).

The present study reports the case of a 72-year-old

male with NA that underwent a successful resection via an

endoscopic-assisted sublabial and buccolabial incision approach

(6). This case confirms the

occurrence of NA in the elderly, and also highlights the potential

of an endoscopic-assisted sublabial and buccolabial incision

approach for the treatment of NA in elderly patients.

Case report

A 72-year-old male presented with continuous

headaches, right nasal epistaxis, right nasal obstruction and a

decreased sense of smell for three months. The patient was admitted

to the First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang

University (Hangzhou, China) on March 29, 2013, three months after

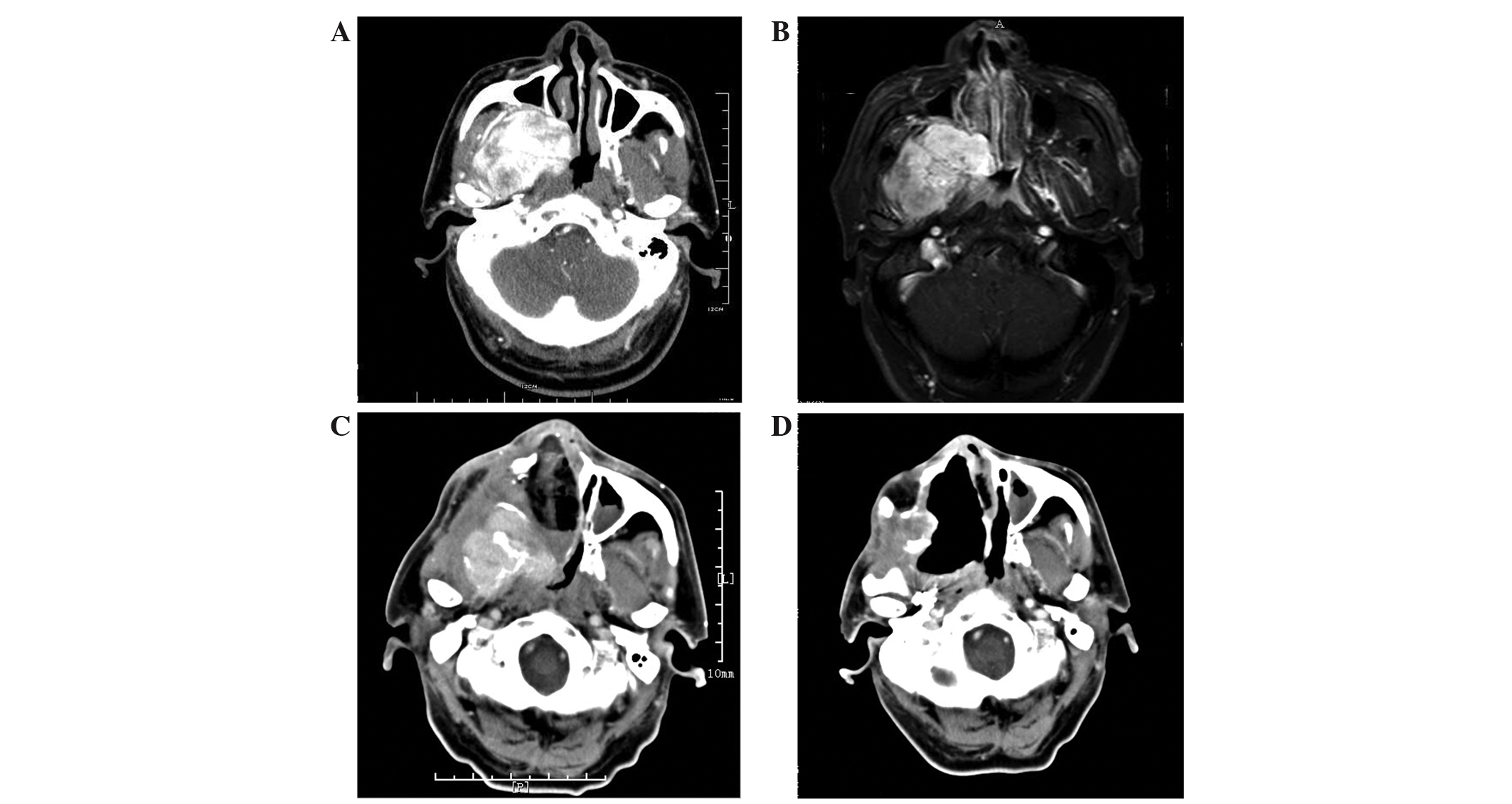

the initial onset of these symptoms. The contrast-enhanced computed

tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a

highly vascular nasopharyngeal mass, and the sphenomaxillary fossa

was enlarged (Fig. 1A and B).

Surgical resection was performed using a lateral rhinotomy

approach. However, due to massive hemorrhage, the tumor was not

completely removed. Histopathological examination of the excised

lesion revealed the presence of angiofibroma. Five months after

surgery, the patient presented with recurrent right spontaneous

epistaxis and right nasal obstruction and was subsequently referred

to the Fudan University Affiliated Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat

Hospital (Shanghai, China) to receive additional treatment.

A physical examination at our hospital revealed a

red mass in the right nasal cavity. Contrast-enhanced CT confirmed

the presence of a large soft-tissue nasal and nasopharyngeal mass

that extended into the right maxillary antrum and up towards the

orbital floor, with destruction of the medial and lateral walls of

the antrum, into the sphenoid sinus on the right side and continued

dorsally to the right parapharyngeal space and infratemporal fossa

(Fig. 1C).

An endoscopic-assisted sublabial and buccolabial

incision approach was used to remove the tumor following

pre-operative embolization. Using clamp forceps, the nasal

component of the tumor was pushed down into the nasopharynx and

drawn out through the oral cavity. In order to remove the

infratemporal fossa extension of the NA, a sublabial and

buccolabial incision, which extended from the first molar teeth to

the maxillary tuberosity at the gingivobuccal sulcus, was made on

the involved side. Due to the complex anatomy and high vascularity

of the region, a blood loss of ~2,800 ml occurred during the

surgery. The patient therefore received a blood transfusion of 400

ml fresh frozen plasma and 4 units of packed red blood cells. The

extensive hemorrhage also led to a poor surgical field. In order to

prevent accidental injury, the surgery was terminated without

further investigation. A contrast-enhanced CT scan was performed

the next day to determine whether the tumor had been completely

removed. The results revealed the presence of residual tumor in the

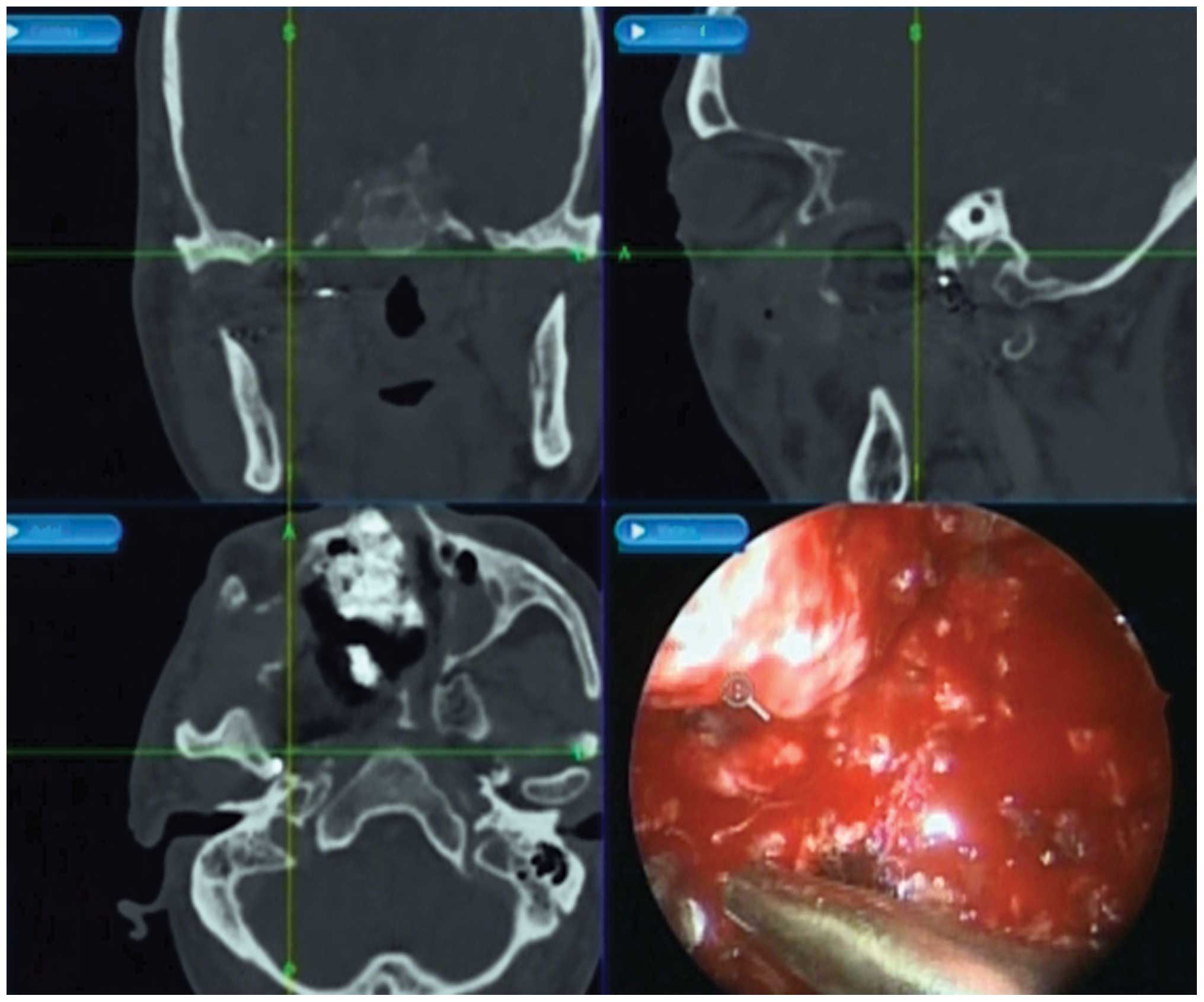

right parapharyngeal space and infratemporal fossa. A day later, a

repeat endoscopic-assisted sublabial and buccolabial incision

approach was performed to remove the residual tumor. An

image-guided navigation system (Medtronic, Louisville, KY, USA) was

used for the localization of the residual tumor in the right

parapharyngeal space and infratemporal fossa (Fig. 2). A contrast-enhanced CT scan

performed 2 weeks subsequent to the procedure confirmed the

complete removal of the tumor (Fig.

1D). The patient was followed up for 6 months, without

exhibiting evidence of recurrence.

A hematoxylin and eosin-stained section revealed

that the tumor was composed of a characteristic fibrous stroma in

which the vascular channels were lined by flat endothelial cells

(Fig. 3A). A Van-Gieson-stained

section established that the tumor was mainly composed of collagen

fibers, while elastic fibers were scarcely discernible (Fig. 3B). Immunohistochemically, the tumor

was positive for the expression of cluster of differentiation

(CD)31 (Fig. 3C), CD34 (Fig. 3D), CD68 (Fig. 3E), HHF35 (Fig. 3F), smooth muscle actin (Fig. 3G), and vimentin (Fig. 3H). The percentage of Ki-67-positive

cells was 4% (Fig. 3I). According to

these findings, a diagnosis of angiofibroma was established.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Fudan University Affiliated Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital, and

written informed consent was obtained from the patient and the

patient's family.

Discussion

In general, NA primarily affects adolescent males,

and is therefore considered to be a juvenile disease. However, NA

has been observed in at least three patients over the age of 70

(Table I), consisting of a

79-year-old male (7), a 71-year-old

female (8) and a 70-year-old male

(9). These patients were treated by

traditional open surgical approaches and the diagnoses were lacking

in immunohistochemical evidence. According to Patrocinio et

al (10), immunohistochemical

analyses are required for the diagnosis of atypical NA cases,

particularly those with atypical clinical manifestations. The

immune profile is extremely useful during the process of

pathological differential diagnosis.

| Table I.Three patients over the age of 70

diagnosed with nasopharyngeal angiofibroma. |

Table I.

Three patients over the age of 70

diagnosed with nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.

| First author

(ref.) | Gender | Age, years | Surgical

approach |

|---|

| Conley et al

(7) | Male | 79 | Transpalatine or

lateral rhinotomy approach |

| Ewing and Shively

(8) | Female | 71 | Right lateral

rhinotomy and antrotomy |

| Shaheen (9) | Male | 70 | Moure's lateral

rhinotomy incision |

The present study reported a rare case of NA in a

72-year-old male, which was confirmed by histopathological and

immunohistochemical analysis. With the exception of age, the

patient demonstrated typical presentation, clinical examination and

radiological findings (Fig. 1).

Histologically and immunohistochemically, the tumor was composed of

proliferating vasculature in a fibrous stroma. The presence of

red-colored regions following Van-Gieson staining and a strong

positivity to vimentin indicated that the majority of the stromal

cells were fibrocytes (11). Positive

immunohistochemical staining for the endothelial markers CD31 and

CD34 supported true endothelial differentiation (Fig. 3) (12).

This typical presentation was of significant value for the

diagnosis of NA.

The etiology and pathogenesis of NA remains unclear.

It has been reported that no abnormalities in the serum levels of

dihydrotestosterone, testosterone and estradiol-17 B are detected

in NA patients (13). To a certain

extent, the occurrence of NA in the elderly may support the

hypothesis that serum androgen levels do not affect the development

of NA, since low serum androgen levels are present in older men

(14,15).

Large NAs continue to present a considerable

surgical challenge (1,6). The optimal treatment for these tumors is

gross total resection. However, open approaches require external

and internal incisions, which results in extensive soft-tissue

dissection and multiple osteotomies (3). Improvements in pre-operative assessment

and preparation, in addition to operative techniques and

instrumentation, may enable the endoscopic removal of the majority

of juvenile NAs (16). If the

location or extension of the tumor is too lateral or inferior to be

effectively resected by an endoscopic approach, a combination of

endoscopic and open approaches may be considered (17,18). It

has previously been reported that an endoscopic-assisted sublabial

and buccolabial incision is an optional approach for the removal of

an NA with extensive infratemporal fossa extension in youths

(6). The present case confirmed that

this modified surgery is well tolerated by the elderly. Due to a

firm connection with surrounding structures, the tumor may break

during surgery, leaving remnants in the surgical cavity, which

poses a challenge for effective treatment. As a result of tumor

extension and massive intraoperative hemorrhage, complete resection

of the tumor was unsuccessful following the first

endoscopic-assisted sublabial and buccolabial incision approach in

the current case. Therefore, a revision surgery was considered.

Image-guided navigation systems are useful for the localization of

deep located tumors (19). In the

present study, radiographical analysis revealed that the tumor had

been completely resected following image-guided surgery. This

counter example illustrated the value of the image-guided

navigation system.

The present study confirmed the occurrence of NA in

the elderly and highlighted the potential of an image-guided

endoscopic-assisted sublabial and buccolabial incision approach for

the treatment of NA in the elderly. In addition, the present study

established that image-guided navigation systems are useful for the

localization of deep NA lesions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient for his

contribution to this work. This work was supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81371077) and by

Shanghai Municipal Hospitals' Rising and Leading Technology Program

(grant no. SHDC12013121).

References

|

1

|

Sun XC, Wang DH, Yu HP, et al: Analysis of

risk factors associated with recurrence of nasopharyngeal

angiofibroma. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 39:56–61.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Boghani Z, Husain Q, Kanumuri VV, et al:

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: A systematic review and

comparison of endoscopic, endoscopic-assisted and open resection in

1047 cases. Laryngoscope. 123:859–869. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Huang Y, Liu Z, Wang J, et al: Surgical

management of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: Analysis of 162

cases from 1995 to 2012. Laryngoscope. 124:1942–1946. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Tang IP, Shashinder S, Gopala Krishnan G

and Narayanan P: Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma in a tertiary

centre: Ten-year experience. Singapore Med J. 50:261–264.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Paris J, Guelfucci B, Moulin G, et al:

Diagnosis and treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.

Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 258:120–124. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sun XC, Li H, Liu ZF, et al:

Endoscopic-assisted sublabial and buccolabial incision approach for

juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with extensive infratemporal

fossa extension. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 76:1501–1506.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Conley J, Healey WV, Blaugrund SM and

Erzin KH: Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma in the juvenile. Surg Gynecol

Obstet. 126:825–837. 1968.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ewing JA and Shively EH: Angiofibroma: a

rare case in an elderly female. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

89:602–603. 1981.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Shaheen HB: Nasopharyngeal fibroma. J

Laryngol Otol. 45:259–264. 1930. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Patrocínio JA, Patrocínio LG, Borba BH, et

al: Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma in an elderly woman. Am J

Otolaryngol. 26:198–200. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bornemann A and Schmalbruch H:

Anti-vimentin staining in muscle pathology. Neuropathol Appl

Neurobiol. 19:414–419. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Pusztaszeri MP, Seelentag W and Bosman FT:

Immunohistochemical expression of endothelial markers CD31, CD34,

von Willebrand factor, and Fli-1 in normal human tissues. J

Histochem Cytochem. 54:385–395. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Farag MM, Ghanimah SE, Ragaie A and Saleem

TH: Hormonal receptors in juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma.

Laryngoscope. 97:208–211. 1987. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ferrini RL and Barrett-Connor E: Sex

hormones and age: a cross-sectional study of testosterone and

estradiol and their bioavailable fractions in community-dwelling

men. Am J Epidemiol. 147:750–754. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Laughlin GA, Barrett-Connor E and

Bergstrom J: Low serum testosterone and mortality in older men. J

Clin Endocrinol Metab. 93:68–75. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Douglas R and Wormald PJ: Endoscopic

surgery for juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma: Where are the

limits? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 14:1–5. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Khalifa MA and Ragab SM: Endoscopic

assisted antral window approach for type III nasopharyngeal

angiofibroma with infratemporal fossa extension. Int J Pediatr

Otorhinolaryngol. 72:1855–1860. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Gallia GL, Ramanathan M Jr, Blitz AM and

Reh DD: Expanded endonasal endoscopic approach for resection of a

juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma with skull base involvement. J

Clin Neurosci. 17:1423–1427. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Farhadi M, Jalessi M, Sharifi G, et al:

Use of image guidance in endoscopic endonasal surgeries: A 5-year

experience. B-ENT. 7:277–282. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|