Introduction

Meningioma is a common intracranial tumour,

accounting for 13–19% of all primary brain tumors (1). This tumor is generally encapsulated and

benign (2). The symptoms of

meningioma depend on the pressure of the tumor on the brain or

spinal cord and the intracranial location of the tumor (3). Symptoms, such as seizures, single or

multiple muscle twitches, spasms, loss of control of body

functions, change in sensation and partial or total loss of

consciousness, are associated with the different locations of the

mass (1,4). Meningiomas accounted for ~33.8% of all

the primary brain and central nervous system tumors reported in the

United States between 2002 and 2006 (2). Furthermore, in recent decades, increased

exposure to risk factors has determined an increase in the

incidence of primary brain tumors, inclusive of meningioma, in

several countries (5). The

predominant risk factor identified is the exposure to ionizing

radiation; however, other risk factors may be associated with the

risk of meningioma, including elevated estrogen and/or progesterone

hormone levels (2,6,7), head

trauma (2), cell phone use (2,8), breast

cancer (2), occupation (2), diet (2).

Notably, a significant inverse correlation has been identified

between meningioma and allergies (2,9); Linos

et al (10) revealed that

individuals with a history of allergy exhibited a lower risk of

developing brain tumours than individuals with no history of

allergy. Meningiomas have a higher incidence rate among female

individuals, with a female to male ratio of ~2:1 (5). In addition, age-specific incidence rates

indicate that risk increases with age. Prevalence rates for

non-Hispanic individuals of African descent are marginally higher

(6.67 per 100,000 persons) compared with Caucasian non-Hispanic and

Hispanic individuals (5.90 and 5.94 per 100,000 persons,

respectively) (2,4). The primary treatment strategy for

meningiomas is total resection surgery if the tumor is benign and

in an area of the brain where it can be safely and completely

removed. Subsequently, radiation therapy is applied for the most

malignant cases of meningioma or when surgery is not feasible due

to the meningioma location.

Extracranial meningiomas are uncommon (accounting

for <2% of meningiomas) (11),

particularly those extending into the middle ear. The present study

described a rare case of meningioma extending into the middle ear

from the middle cranial fossa through the tegmen tympani. Written

informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Case report

In May 2004, a 56-year-old woman presented to the

Ear Nose and Throat Unit of Santa Maria delle Grazie Hospital

(Naples, Italy) with an intense headache associated with vertigo

that was treated with intravenous administration of 10% glycerol

and 8 mg dexamethasone, with no results. After approximately two

months, the patient had developed generalized seizure episodes.

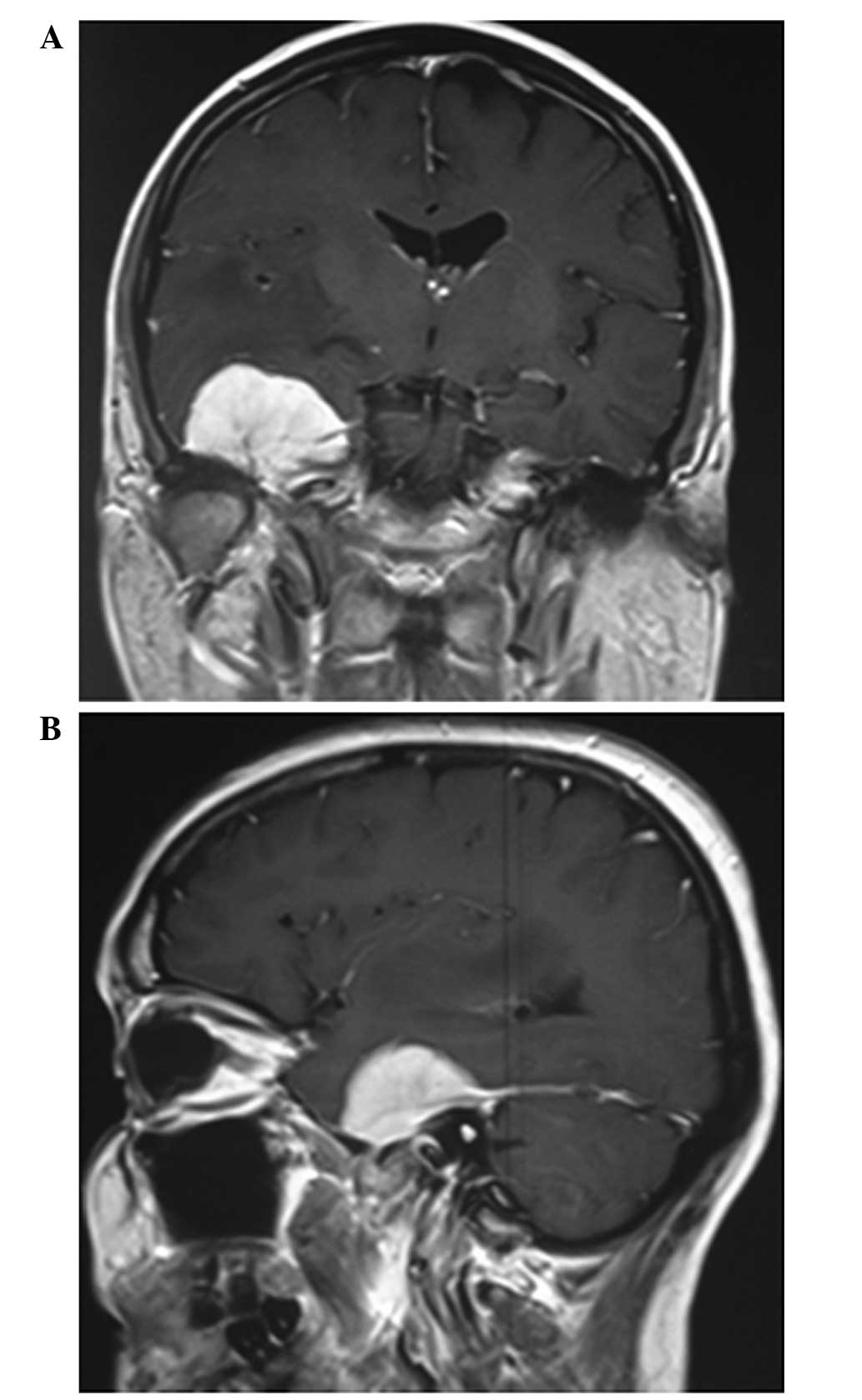

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium revealed the

presence of a large (37×40×25 mm), T1-hypointense lesion widely

invading the right middle cranial fossa with compression of the

adjacent structures and dislocation of the middle cerebral artery.

In addition, the lesion exhibited high contrast enhancement and a

dural tail (Fig. 1A and B). Based on

these radiological features of the lesion, a diagnosis of

meningioma was determined. A right pterional craniotomy with

partial extirpation of the lesion was performed, since the tumor

presented a large and deep implantation base on the tentorial dura

of the petrous bone roof.

The postoperative course was uneventful.

Histopathological examination of the excised tumor determined a

diagnosis of transitional meningioma. Subsequently, the patient

underwent postoperative stereotactic radiotherapy (200 cGy, six

days a week) for five weeks, to treat the residual tumor, and

clinico-radiological follow-up.

In March 2006, two years after surgery, the patient

underwent appositional transtympanic drainage in the right ear due

to right chronic otitis media with effusion at the Complex Unit of

Otolaryngology and Neck Surgery of Monaldi Hospital (Naples,

Italy); however, no substantial clinical improvement occurred. The

patient experienced progressive worsening of right-ear hearing

loss, otorrhea and otalgia, despite frequent antibiotic therapies

(with quinolones and cephalosporins). Therefore, the patient

underwent petrous bone computed tomography (CT). The CT scan

identified an intratympanic mass that enveloped the ossicular chain

without erosion and thickening of the tegmen tympani (Fig. 2A and B).

In January 2010, the patient was admitted to the Ear

Nose and Throat Unit of Santa Maria delle Grazie Hospital with

right otalgia, otorrhea, vertigo and increasing right hypoacusis,

which had occurred intermittently for the past 20 years. A right

otomicroscopy identified granulation tissue in the drainage tube

and the hyperemic, bulging and everted tympanic membrane. A pure

tone audiogram determined right anacusis and left-sided

sensorineural hearing loss. In addition, pre-operative brain MRI

confirmed the presence of a hyperintense tissue mass, occupying the

tympanic cavity (Fig. 3).

Consequently, a right canal-wall-down (CWD)

tympanoplasty was performed. A granulomatous-like mass invading the

tympanic cavity, mastoid antrum and oval window was removed

(Fig. 4). Histological analysis

confirmed the lesion to be transitional meningioma with identical

histology to the previous tumor and thus, it was considered to be a

section of the tumor that was resected in 2004.

The patient underwent clinico-radiological follow-up

and, five years later, exhibited no evidence of middle ear tumor

recurrence (Fig. 5).

Discussion

Meningioma is a common intracranial tumor,

accounting for 13–19% of all the primary brain tumors (1). Meningiomas are slow-growing and

originate from the arachnoid villi of the meninges (11). Extracranial meningioma are uncommon

(accounting for <2% of meningiomas) (11), particularly those extending into the

middle ear. Furthermore, the majority of intracranial meningiomas

are benign (90%), with atypical (6%) and malignant forms (2%)

occurring less frequently (12).

Meningiomas are typically diagnosed in adults aged

>60 years and the incidence rate increases with age. In

addition, these tumors occur more often in women than in men

(13). Depending on the location of

the tumor, patients can present with a variety of neurological

symptoms, including headaches, speech problems, visual

disturbances, cognitive deficits, motor deficits and epilepsy

(4). In cases of temporal bone

meningioma, otalgia is the most common feature, although hearing

loss (conductive, mixed or sensorineural) (14), facial palsy and tinnitus are also

common (15). A lower proportion of

patients present with other cranial nerve palsies or vestibular

symptoms (16).

In the current case, the patient exhibited a middle

fossa meningioma that presented with epileptic seizures and

symptoms of chronic otitis media. Chronic otitis media has been

reported to occur in 16% of intratympanic meningiomas (17), possibly due to the obstruction of the

Eustachian tube upon extension of the tumor into the middle ear

cavity. Temporal bone meningioma scans follow multiple extension

pathways: The tegmen tympani, the jugular foramen and the internal

auditory canal (16). Based on their

imaging characteristics, meningiomas are stratified into three

groups with different primary locations and vectors of spread. The

jugular foramen and tegmen tympani meningiomas are characterized by

spread to the middle ear cavity. By contrast, internal auditory

canal meningiomas spread to the intralabyrinthine structures

(18). In the present case,

meningioma primary to the tegmen tympani arose from the floor of

the middle cranial fossa and spread inferomedially into the middle

ear cavity. A number of radiological features (including thickening

of the tegmen tympani, absence of bone and ossicular erosion and

contrast enhancement of the lesion) (18) helped to distinguish meningioma from

cholesteatoma in the current study. Furthermore, the jugular

foramen, internal acoustic canal and labyrinthic area appeared

healthy and free of disease.

Four histological subtypes of meningioma have been

reported thus far: Meningotheliomatous, transitional, fibrous and

angioblastic. Extracranial meningiomas are more often transitional

or meningotheliomatous (19). In the

present case, the extracranial lesion was diagnosed as a

transitional meningioma.

Surgery is the treatment of choice for meningioma,

with overall survival rates of 85, 75 and 70% at 5, 10 and 15

years, respectively. However, complete resection is often not

considered to be possible, particularly in large tumors (20). Furthermore, in contrast to their

intracranial counterparts, meningiomas involving the temporal bone

do not often exhibit well-demarcated tumor margins (21).

The role of radiotherapy in the treatment of

meningiomas remains controversial and is generally reserved for the

adjuvant treatment of non-radically removed or recurrent

meningiomas (19). Thus, in the

present case, the patient underwent neurosurgical therapy with

successive radiotherapy. Due to the persistence of the residual

tumor in middle fossa for a number of years, the patient underwent

a CWD tympanoplasty for the middle ear tumor.

In conclusion, temporal bone meningioma involving

the middle ear is uncommon. Due to presenting similar symptoms with

chronic otitis media, diagnosing meningioma is often difficult.

However, imaging techniques can facilitate distinguishing between

meningioma tumors and other diseases of the middle ear. In

particular, in cases of hyperplastic chronic otitis media in

patients with a previous meningioma, a temporal bone CT and MRI

with gadolinium should be performed. Furthermore, treatment

typically requires sequential neurosurgical and otosurgical

approaches, followed by postoperative radiotherapy in cases of

partial exeresis.

References

|

1

|

Prayson RA: Middle ear meningiomas. Ann

Diagn Pathol. 14:149–153. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wiemels J, Wrensch M and Claus EB:

Epidemiology and etiology of meningioma. J Neurooncol. 99:307–314.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

American Society of Clinical

Oncology:Meningioma: Symptoms and Signs. http://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/meningioma/symptoms-and-signsAccessed.

January 13–2015.

|

|

4

|

vanAlkemade H, de Leau M, Dieleman EM,

Kardaun JW, van Os R, Vandertop WP, van Furth WR and Stalpers LJ:

Impaired survival and long-term neurological problems in benign

meningioma. Neuro Oncol. 14:658–666. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United

States, . CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Central

Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in Eighteen States in

2002–2006CBTRUS. Hinsdale, IL: pp. 13–26. 2009–2010

|

|

6

|

Claus EB, Black PM, Bondy ML, Calvocoressi

L, Schildkraut JM, Wiemels JL and Wrensch M: Exogenous hormone use

and meningioma risk: what do we tell our patients? Cancer.

110:471–476. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Vadivelu S, Sharer L and Schulder M:

Regression of multiple intracranial meningiomas after cessation of

long-term progesterone agonist therapy. J Neurosurg. 112:920–924.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Inskip PD, Tarone RE, Hatch EE, Wilcosky

TC, Shapiro WR, Selker RG, Fine HA, Black PM, Loeffler JS and Linet

MS: Cellular-telephone use and brain tumors. N Engl J Med.

344:79–86. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Schoemaker MJ, Swerdlow AJ, Hepworth SJ,

van Tongeren M, Muir KR and McKinney PA: History of allergic

disease and risk of meningioma. Am J Epidemiol. 165:477–485. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Linos E, Raine T, Alonso A and Michaud D:

Atopy and risk of brain tumors: A meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer

Inst. 99:1544–1550. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

George M, Ikonomidis C, Pusztaszeri M and

Monnier P: Primary meningioma of the middle ear: case report. J

Laryngol Otol. 124:572–574. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rowland LP: Tumors of the

meningesMerritt's Neurology. 10th. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins;

Philadelphia, PA: pp. 250–253. 2000

|

|

13

|

Ozbayir T, Malak AT, Bektas M, Ilce AO and

Celik GO: Information needs of patients with meningiomas. Asian Pac

J Cancer Prev. 12:439–441. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Thompson LD, Bouffard JP, Sandberg GD and

Mena H: Primary ear and temporal bone meningiomas: a

clinicopathologic study of 36 cases with a review of the

literature. Mod Pathol. 16:236–245. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Pankhania M, Rourke T and Draper MR: The

middle ear mass: a rare but important diagnosis. BMJ Case Rep. Dec

2–2011.(Epub ahead of print). View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chang CY, Cheung SW and Jackler RK:

Meningiomas presenting in the temporal bone: the pathways of spread

from an intracranial site of origin. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

119:658–664. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Batsakis JG: Pathology consultation.

Extracranial meningiomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 93:282–283.

1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Hamilton BE, Salzman KL, Patel N, Wiggins

RH III, Macdonald AJ, Shelton C, Wallace RC, Cure J and Harnsberger

HR: Imaging and clinical characteristics of temporal bone

meningioma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 27:2204–2209. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Tsunoda R and Fukaya T: Extracranial

meningioma presenting as a tumour of the external auditory meatus:

a case report. J Laryngol Otol. 111:148–151. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Marosi C, Hassler M, Roessler K, Reni M,

Sant M, Mazza E and Vecht C: Meningioma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

67:153–171. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rietz DR, Ford CN, Kurtycz DF, Brandenburg

JH and Hafez GR: Significance of apparent intratympanic

meningiomas. Laryngoscope. 93:1397–1404. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|