Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) is a rare autosomal

dominant syndrome that is characterized by the presence of

bilateral vestibular schwannomas (VS; acoustic neuroma). In certain

patients, the disease may be complicated by meningioma, ependymoma,

spinal schwannomas or vitreous opacities. The growth of VS may lead

to brain stem compression, tinnitus, progressive hearing loss,

deafness, ataxia and eventual mortality. The incidence of NF2 in

the population is 1 in 40,000–33,000, and 50% of the cases

represent sporadic mutation, while the other half inherit the

disease from their parents (1).

Microsurgery for tumor resection and stereotactic radiotherapy are

the standard treatment strategies; however, these may sacrifice

hearing to achieve tumor control.

A vast amount of data has indicated that

angiogenesis is pivotal for tumor growth, and vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF) is a vital factor affecting angiogenesis and

vascular permeability. Therefore, molecular targeted treatment may

be promising for NF2-related tumors. Bevacizumab is the first Food

and Drug Administration-approved monoclonal antibody that is able

to neutralize the activity of VEGF in order to inhibit

angiogenesis, tumor metastasis and growth, specifically (2). Bevacizumab has been used to treat

malignant tumors, including metastatic rectal carcinoma and

advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Plotkin et al (3) previously achieved a favorable outcome by

treating NF2 with bevacizumab [5 mg/kg/2 weeks; intravenous

injection (IV)], including radiographic tumor regression and

hearing improvement. To the best of our knowledge, the optimal

regimen remains to be defined. A dosage of 5 mg/kg/2 weeks is

widely used; however, this may induce adverse effects, including

hypertension, thrombosis or delayed wound healing. Thus,

establishing a well-tolerated therapy would be promising for

patients, given the adverse effects of bevacizumab.

In the present case involving a patient with

bilateral VS in NF2, a lowered dose of bevacizumab and protracted

infusion interval was trialled so as to explore the efficacy of

low-dose bevacizumab regimen in inhibiting tumor growth and

minimizing the adverse effects.

Case report

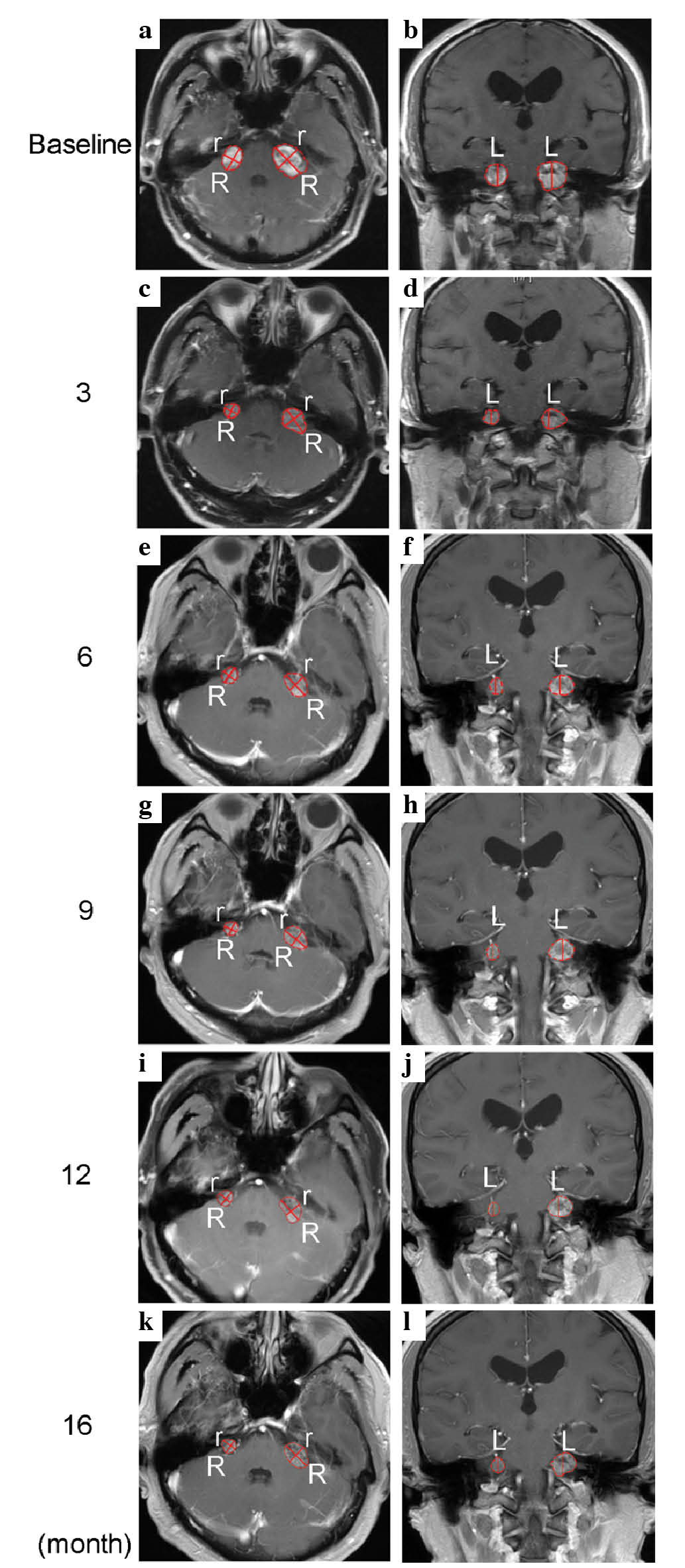

A 55-year-old man who was suffering with left

progressive hearing loss and facial weakness was misdiagnosed with

nerve deafness in 2007 at Binzhou Medical University Hospital

(Binzhou, China). The patient presented right hearing loss in April

2009. On February 25, 2013, contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI; Signa HDx 3.0T and 1.5T MR; GE Healthcare Life

Sciences) (Fig. 1) revealed bilateral

VS measuring 5.25 and 2.54 cm3 on the left and right,

respectively (Fig. 1a–b). No mass

effects were detected on MRI of the spinal cord. Café au

lait spots (3×2 cm) were noted in the left anterior tibial

skin. The patient was conscious without nystagmus, and his left

nasolabial groove was shallower than the right. These findings

confirmed a diagnosis of NF2. The pure tone average (PTA) threshold

of 0.5, 1 and 2 kHz tones presented by bone-conduction indicated an

impaired capacity for bilateral language recognition (Fig. 2). However, the patient refused

microsurgical tumor resection and gamma knife therapy due to fears

of surgery complications. On February 28, 2013, bevacizumab (Roche

Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) was administered by IV to

inhibit tumor growth and avoid further deterioration of hearing

initially. The drug dose was calculated according to patient's body

weight (91 kg). Initially, 300 mg (91 kgx3.3 mg/kg) was

administered every 2 weeks for 3 months. Subsequently, the dose of

bevacizumab was gradually lowered to 2.2 mg/kg every 4 weeks in

order to avoid adverse effects. Given that the patient had history

of hypertension, felodipine (5 mg/day) was administered orally to

maintain the patient's blood pressure within a normal range.

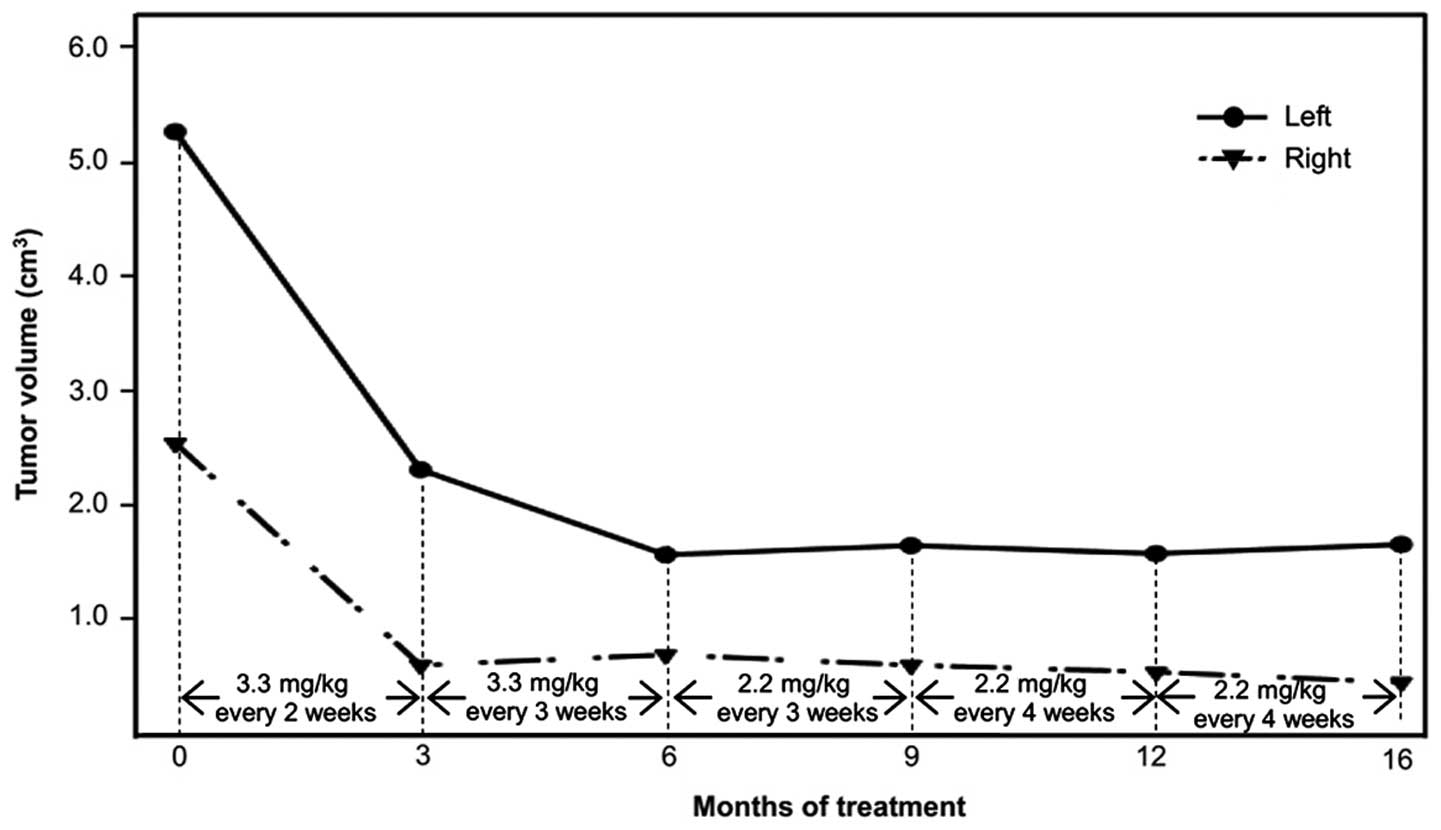

Following bevacizumab treatment (3.3 mg/kg, every 2

weeks) for a period of 3 months, the patient's hearing level

remained stable without deterioration and the bilateral VS

regressed by 56% and 76% on the left and right, respectively

(Figs. 1c–d and 2). The central part of tumor was not well

enhanced due to the rapid inhibition of angiogenesis by

bevacizumab. On June 17, 2013, the patient was recommenced on

bevacizumab (3.3 mg/kg, every 3 weeks), administered by IV, for the

next 3 months. His hearing remained stable as before and the left

VS further regressed by 13%, while the right VS remained stable

(Figs. 1e–f and 2). Given the adverse effects induced by

bevacizumab, including anemia, neutropenia and lymphocytopenia

(4), on September 14, 2013, the dose

was further lowered to 2.2 mg/kg and the infusion interval

protracted to 4 weeks so as to reduce the risk of hypertension

aggravated by bevacizumab whilst preventing tumor recurrence

following drug discontinuation.

After a constant treatment (2.2 mg/kg) for 1 year,

the patient's hearing was successfully preserved by low-dose

bevacizumab, without further progression (Fig. 3). Although no hearing improvement was

detected by pure tone audiometry (using the Madsen Midimate 622

audiometer; GN Otometrics, Taastrup, Denmark), the patient

subjectively experienced a significant hearing improvement as his

ability to communicate with people and distinguish voices was

restored. Compared with baseline measurements prior to treatment,

the bilateral VS regressed by 3.59 cm3 (68%) and 2.08

cm3 (82%) on the left and right, respectively (Fig. 1g–l; Table

I). At the time of writing, the patient was continuing to

receive bevacizumab treatment (2.2 mg/kg, every 4 weeks) by IV

without any significant adverse effects observed, and with no signs

of tumor progression or hearing deterioration.

| Table I.Tumor size analysis. |

Table I.

Tumor size analysis.

|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | 16 months |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Dimension | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right | Left | Right |

|---|

| R, mm | 27.5 | 18.3 | 20.0 | 11.0 | 17.7 | 11.1 | 17.8 | 11.6 | 17.2 | 10.9 | 18.2 | 9.8 |

| r, mm | 18.7 | 15.6 | 15.1 | 10.5 | 12.1 | 10.6 | 13.4 | 10.6 | 12.6 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 9.4 |

| L, mm | 19.5 | 17.0 | 14.6 | 10.1 | 14.0 | 11.3 | 13.2 | 9.5 | 13.9 | 9.3 | 15.4 | 9.5 |

| V,

cm3 | 5.25 | 2.54 | 2.31 | 0.61 | 1.57 | 0.70 | 1.65 | 0.61 | 1.58 | 0.55 | 1.66 | 0.46 |

Discussion

A complete literature review was conducted using

computer search engines in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) to identify all

cases of VS in NF2 treated with bevacizumab. The search was

performed using single or combined search terms, including

‘bevacizumab’, ‘bilateral vestibular schwannomas’,

‘neurofibromatosis 2’ and ‘adverse effects’. In total, 6 relevant

reports comprising 39 cases of VS in NF2, published between 2010

and 2014, were included (3,5–9). The

clinical characteristics are summarized in Table II, including drug dose, number of

patients, treatment duration, mean age and adverse effects.

Radiological response and hearing status are detailed in Table III. All patients received

bevacizumab 5 mg/kg/2 weeks by IV. The mean age was 26±2.2 years

(range, 12–73 years). The median duration of treatment was 12

months, and 85% of the patients (33/39) experienced tumor

regression. The median tumor volume reduction was 27.5% (range,

3–91%). The solid component regressed less than the cystic

component of the tumor (8). However,

the findings also indicate that tumor regrowth may occur after drug

discontinuation (9). The rate of

hearing improvement was 45.2% (14/31), whilst the rate of hearing

stability was 48.4% (15/31). Hearing loss was observed during

treatment intermission and disappeared after treatment resumed

(7). Plotkin et al (7) reported bevacizumab treatment for

progressive VS in 31 patients with a 3-year follow-up. The rates of

tumor stability or regression were 88% at 1 year, 67% at 2 years

and 54% at 3 years. The rates of hearing stability or improvement

were 90% at 1 year, 81% at 2 years, and 61% at 3 years. However,

168 adverse events were identified during 572 patient-months of

treatment. The frequency of adverse events was high, demonstrating

how adverse effects have become an obstacle for the clinical use of

bevacizumab.

| Table II.Summary of patient characteristics and

adverse effects in previous studies. |

Table II.

Summary of patient characteristics and

adverse effects in previous studies.

| Author, year | Dose | Patients, n | Median duration

(range), months | Mean age (range),

years | Adverse effects | Ref. |

|---|

| Subbiah et al,

2012 | 5 mg/kg IV/2 wk | 2a | 9.5 (9–10) | 28.5 (16–41) | No significant

adverse effects | (5) |

| Eminowicz et

al, 2012 | 5 mg/kg IV/2 wk | 2 | 3.5 (3–4) | 34 (31–37) | No significant

adverse effects | (6) |

| Plotkin et al,

2012 | 5 mg/kg IV/2 wk | 31 | 14 (6–41) | 26 (12–73) | Hypertension,

proteinuria, menorrhagia, epistaxis, pneumonia | (7) |

| Plotkin et al,

2009 | 5 mg/kg IV/2 wk | 10 | 12 (3–19) | 25 (16–53) | Hypertension,

proteinuria, menorrhagia, epistaxis, pneumonia | (3) |

| Mautner et al,

2010 | 5 mg/kg IV/2 wk | 2 | 4.5 (3–6) | 32 (24–40) | No significant

adverse effects | (8) |

| Mautner et al,

2010 | 5 mg/kg IV/2–4

wk | 2 | 15 (12–18) | 30 (22–38) | Hypertension | (9) |

| Table III.Summary of radiological response and

hearing status after the treatment. |

Table III.

Summary of radiological response and

hearing status after the treatment.

|

|

|

| Hearing status, %

(n)a |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Author, year | Tumor reduction,

median (range) | No. of patients

experiencing tumor regression | Improved | Stable | Declined | Ref. |

|---|

| Subbiah et

al, 2012 | Stable | 0 of 2 | – | 100 (2 of 2) | – | (5) |

| Eminowicz et

al, 2012 | 30.5% (10–52%) | 2 of 2 | – | 100 (2 of 2) | – | (6) |

| Plotkin et

al, 2012b | 26%

(3–91%) | 27 of 31 | 57 (13 of 23) | 35 (8 of 23) | 8 (2 of 23) | (7) |

| Plotkin et

al, 2009 | 26%

(5–44%) | 9 of

10 | 57 (4 of 7) | 29 (2 of 7) | 14 (1 of 7) | (3) |

| Mautner et

al, 2010 | 42%

(41–43%) | 2 of 2 | – | 100 (2 of 2) | – | (8) |

| Mautner et

al, 2010 | 47.5% (43–52%) | 2 of

2c | 50 (1 of

2)d | 50 (1 of 2) | – | (9) |

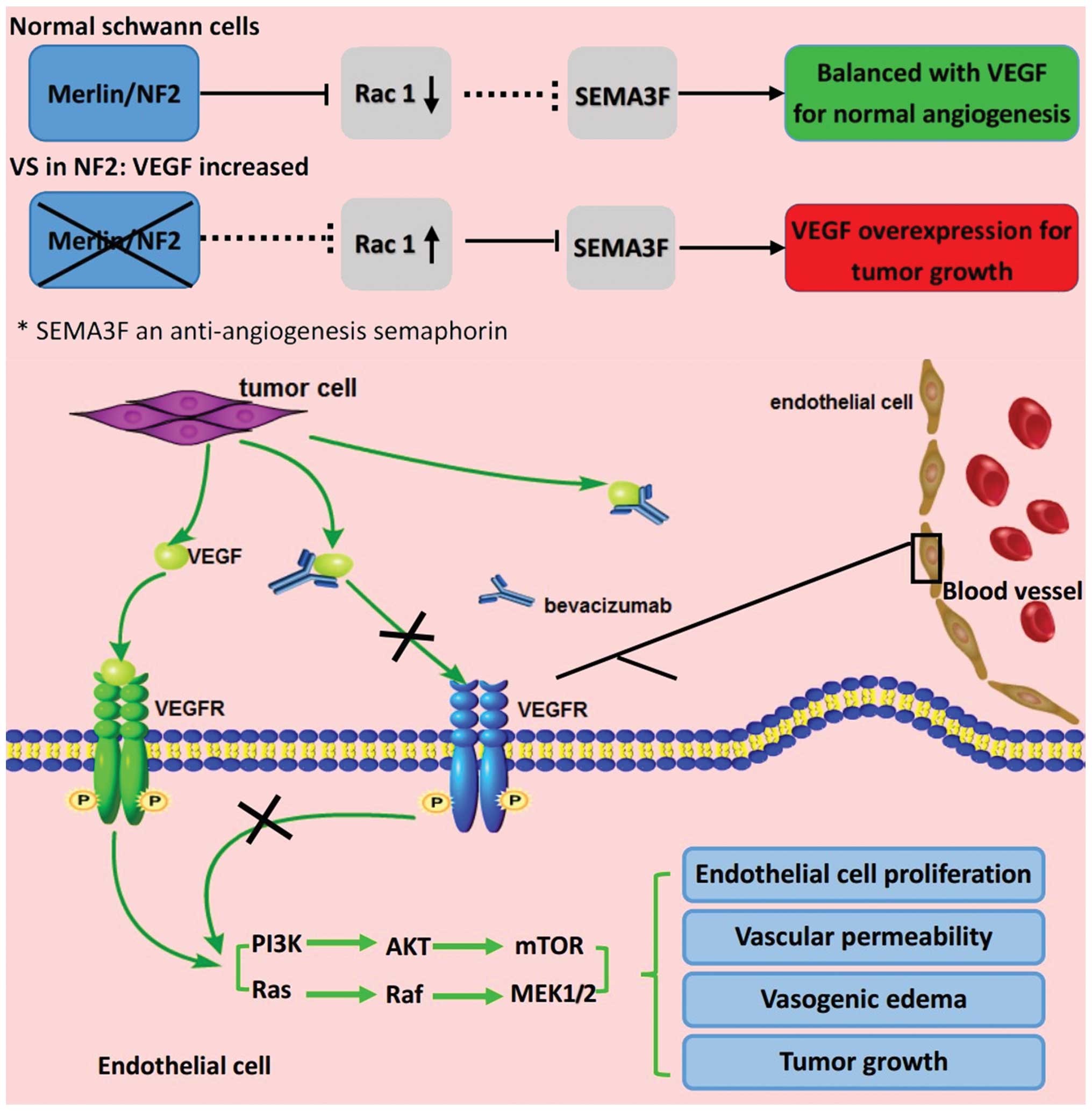

The NF2 tumor suppressor gene has been shown to

reside on chromosome 22q12.2, with the highest mutation rate among

human genetic diseases (10). The

aberration of the NF2 gene may lead to neoplasia of ectodermal and

mesodermal tissues during embryonic development phases by affecting

a variety of signal transduction pathways associated with tumor

genesis and progression, including the phosphoinositide

3-kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway and

the Raf/Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase pathway

(5,11). Loss of a functional NF2 gene product,

Merlin (a tumor suppressor protein), may inhibit the expression of

anti-angiogenesis semaphorin-3F by up regulating the Rac1 pathway

in VS, resulting in a relative surplus of VEGF (12). Furthermore, tumor necrosis occurs when

a tumor's blood supply cannot satisfy its growth, which may

activate the compensatory overexpression of VEGF to improve the

hypoxic microenvironment (12).

Hence, VEGF blockade using bevacizumab may normalize the

vascularity and decrease edema (Fig.

4) (12).

Microsurgery for tumor resection and stereotactic

radiotherapy are usually recommended for VS in NF2 (13). However, patients must abandon hearing

in order to achieve tumor control, and are also subject to possible

postoperative complications, such as cerebrospinal fluid leak and

facial weakness. Unfortunately, postoperative tumor recurrence may

induce the need for reoperation in some patients, resulting in a

decline in quality of life (14). In

the current study, anti-angiogenesis therapy with bevacizumab

objectively induced tumor regression and hearing preservation in a

case of VS in NF2. A low-dose regimen was beneficial for avoiding

significant adverse effects, providing an alternative treatment

strategy instead of surgical intervention.

Compared with baseline measurements prior to

treatment, the bilateral VS regressed by 3.59 cm3 (68%)

and 2.08 cm3 (82%) on the left and right, respectively

(Fig. 1; Table I). The absolute change in tumor volume

was not as significant as the relative change; as the tumors in the

current patient were not very large, a small absolute volume change

may result in a large relative percentage reduction in tumor volume

compared with the baseline. To avoid the potential bias in tumor

volume analysis, relative percentage and absolute volume changes

from baseline were used for comparison. The tumor volume remained

stable in last 10 months without further regression. This suggests

that tumor stability may be a compromise between tumor regression

induced by low-dose regimen and tumor growth.

Although no objective hearing improvement was

detected in the patient, subjective hearing improvement did occur.

Furthermore, the patient's hearing declined during treatment

intermission and recovered after treatment was resumed, while the

tumor volume remained stable. Thus, we hypothesized that hearing

stability was drug-dependent. It is possible that higher-dose

regimens may be helpful for hearing improvement, whilst low-dose

regimens are not. In addition, the biological mechanisms underlying

the effects of bevacizumab for hearing stability may be different

from those for tumor regression, which have been reported

previously (15).

Whether bevacizumab may be used for long-term

treatment remains controversial due to the risk of adverse effects,

which include hypertension, proteinuria, thrombosis and hemorrhage

(7). Furthermore, considering tumor

recurrence following drug discontinuation (9), the optimal dose and duration of

treatment is undetermined. As reported by Zuniga et al

(16), disease recurrence and more

aggressive progression were also detected in the treatment of

malignant glioma following bevacizumab discontinuation. However, no

evidence has indicated that bevacizumab discontinuation leads to

accelerated disease progression. Therefore, the current patient is

undergoing close monitoring to observe the efficacy of low-dose

regimen in avoiding severe adverse effects and tumor recurrence

following drug discontinuation.

Given the adverse effects induced by systemic IV

administration of bevacizumab and the insufficient drug

concentration at the tumor site due to the blood-tumor barrier

(BTB), Riina et al (17)

reported a novel approach involving super-selective intra-arterial

cerebral infusion of bevacizumab following BTB disruption. Of 3

patients, 1 experienced tumor regression of 11% and 19% on the left

and right, respectively. All 3 patients presented hearing

improvement or stability. Appropriate cerebrovascular

interventional therapy may be better in certain circumstances. For

example, with regard to local chemotherapy, cerebrovascular

interventional therapy results in less neurotrauma than craniotomy.

Furthermore, cerebrovascular interventional therapy may benefit

patients exhibiting tumors which extend into the internal auditory

canal, as gross total resection is difficult, patients that cannot

tolerate the adverse effects induced by systemic chemotherapy, and

patients with a Karnofsky performance scale score of ≥60 (18).

As the pathogenesis of NF2 depends on multiple

signaling pathways, the combination of bevacizumab with other

molecular targeted drugs, such as erlotinib and lapatinib

(inhibitors of epidermal growth factor receptor), may generate

synergistic effects (5,19). However, the efficacy of this treatment

must be confirmed by clinical trials containing a larger cohort of

patients.

For the patients who exhibit no response to

bevacizumab, a surgical intervention is recommended following a

4-6-week drug metabolism phase to minimize the risk of

postoperative hemorrhage and delayed wound healing (6,8).

In summary, a low-dose regimen of bevacizumab (2.2

mg/kg/4 weeks, IV) would appear to be promising for patients with

VS in NF2, given the adverse effects triggered by bevacizumab

(4). However, the minimum dose

required to sustain a response to bevacizumab in NF2 patients is

still unknown, and may differ from patient to patient. Finding the

minimum effective dose for individual patients sufficient to

sustain hearing and/or volumetric response would aid in decreasing

toxicity and long-term tolerability. With the scientific

advancements, more comprehensive and safe regimens may be

determined.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Shilei Ni from

the Department of Neurosurgery, Qilu Hospital (Jinan, China) for

the valuable suggestions on study design.

References

|

1

|

Di Maio S, Mrak G, Juric-Sekhar G, Born D,

Mantovani A and Sekhar LN: Clinicopathologic assay of 15 tumor

resections in a family with neurofibromatosis type 2. J Neurol Surg

B Skull Base. 73:90–103. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Claudio PP, Russo G, Kumar CA, Minimo C,

Farina A, Tutton S, Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Angeloni G, Maria V, et

al: pRb2/p130, vascular endothelial growth factor, p27 (KIP1) and

proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in hepatocellular

carcinoma: Their clinical significance. Clin Cancer Res.

10:3509–3517. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Plotkin SR, Stemmer-Rachamimov AO, Barker

FG II, Halpin C, Padera TP, Tyrrell A, Sorensen AG, Jain RK and di

Tomaso E: Hearing improvement after bevacizumab in patients with

neurofibromatosis type 2. N Engl J Med. 361:358–367. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yonezawa S, Miwa K, Shinoda J, Nomura Y,

Asano Y, Nakayama N, Ohe N, Yano H and Iwama T: Bevacizumab

treatment leads to observable morphological and metabolic changes

in brain radiation necrosis. J Neurooncol. 119:101–109. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Subbiah V, Slopis J, Hong DS, Ketonen LM,

Hamilton J, McCutcheon IE and Kurzrock R: Treatment of patients

with advanced neurofibromatosis type 2 with novel molecularly

targeted therapies: From bench to bedside. J Clin Oncol.

30:e64–e68. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Eminowicz GK, Raman R, Conibear J and

Plowman PN: Bevacizumab treatment for vestibular schwannomas in

neurofibromatosis type two: Report of two cases, including

responses after prior gamma knife and vascular endothelial growth

factor inhibition therapy. J Laryngol Otol. 126:79–82. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Plotkin SR, Merker VL, Halpin C, Jennings

D, McKenna MJ, Harris GJ and Barker FG II: Bevacizumab for

progressive vestibular schwannoma in neurofibromatosis type 2: A

retrospective review of 31 patients. Otol Neurotol. 33:1046–1052.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mautner VF, Nguyen R, Kutta H, Fuensterer

C, Bokemeyer C, Hagel C, Friedrich RE and Panse J: Bevacizumab

induces regression of vestibular schwannomas in patients with

neurofibromatosis type 2. Neuro Oncol. 12:14–18. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Mautner VF, Nguyen R, Knecht R and

Bokemeyer C: Radiographic regression of vestibular schwannomas

induced by bevacizumab treatment: Sustain under continuous drug

application and rebound after drug discontinuation. Ann Oncol.

21:2294–2295. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Ferrer M, Schulze A, Gonzalez S, Ferreiro

V, Ciavarelli P, Otero J, Giliberto F, Basso A and Szijan I:

Neurofibromatosis type 2: Molecular and clinical analyses in

argentine sporadic and familial cases. Neurosci Lett. 480:49–54.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Akhmametyeva EM, Mihaylova MM, Luo H,

Kharzai S, Welling DB and Chang LS: Regulation of the

neurofibromatosis 2 gene promoter expression during embryonic

development. Dev Dyn. 235:2771–2785. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

London NR and Gurgel RK: The role of

vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular stability in

diseases of the ear. Laryngoscope. 124:E340–E346. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Carlson ML, Tveiten OV, Driscoll CL,

Goplen FK, Neff BA, Pollock BE, Tombers NM, Castner ML, Finnkirk

MK, Myrseth E, et al: Long-term quality of life in patients with

vestibular schwannoma: An international multicenter cross-sectional

study comparing microsurgery, stereotactic radiosurgery,

observation, and nontumor controls. J Neurosurg. 122:833–842. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Narita Y: Drug review: Safety and efficacy

of bevacizumab for glioblastoma and other brain tumors. Jpn J Clin

Oncol. 43:587–595. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fisher LM, Doherty JK, Lev MH and Slattery

WH: Concordance of bilateral vestibular schwannoma growth and

hearing changes in neurofibromatosis 2: Neurofibromatosis 2 natural

history consortium. Otol Neurotol. 30:835–841. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Zuniga RM, Torcuator R, Jain R, Anderson

J, Doyle T, Ellika S, Schultz L and Mikkelsen T: Efficacy, safety

and patterns of response and recurrence in patients with recurrent

high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab plus irinotecan. J

Neurooncol. 91:329–336. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Riina HA, Burkhardt JK, Santillan A,

Bassani L, Patsalides A and Boockvar JA: Short-term

clinico-radiographic response to super-selective intra-arterial

cerebral infusion of bevacizumab for the treatment of vestibular

schwannomas in neurofibromatosis type 2. Interv Neuroradiol.

18:127–132. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Burkhardt JK, Riina HA, Shin BJ, Moliterno

JA, Hofstetter CP and Boockvar JA: Intra-arterial chemotherapy for

malignant gliomas: A critical analysis. Interv Neuroradiol.

17:286–295. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Lim SH, Ardern-Holmes S, McCowage G and de

Souza P: Systemic therapy in neurofibromatosis type 2. Cancer Treat

Rev. 40:857–861. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|