Introduction

More than 30 years ago, eukaryotic translation

initiation factor 6 (eIF6) was first identified as a protein in

wheat germ (1). This protein

functions as an anti-association factor to interact with the 60S

ribosome, and prevent the assembly of the 60S and 40S subunits in

the cytoplasm (2–5). eIF6 is found in yeast and mammalian

cells, and the majority of eIF6 is located in the cytoplasm of

mammalian cells (4,5). Originally, eIF6 was first observed in

the proliferating compartment of the colonic epithelium and stem

cells (6), and is also highly

expressed in epithelial and embryonic tissues (7–9).

Furthermore, an increasing number of studies have demonstrated that

eIF6 is overexpressed in human cancer (6,10–15). Accumulating evidence suggests that

eIF6 is a useful biomarker in cancer diagnosis, and that it serves

as an anti-cancer molecular target. However, the specific role of

eIF6 in tumorigenesis remains to be elucidated.

The present review focuses on eIF6-associated

studies, particularly those pertaining to its subcellular location,

phosphorylation and dephosphorylation, roles in cancer and

molecular mechanisms in oncogenesis.

Subcellular localization of eIF6

eIF6, also known as integrin β4 binding protein,

p27BBP or β4 integrin interactor, is a remarkably conserved protein

from yeast to mammals (7,13–14). In

yeast, eIF6 is primarily localized in the nucleolus (9–10). By

contrast, in mammalian cells, the majority of eIF6 is present in

the cytoplasm, with a smaller but significant fraction (~30%)

located in the nucleus (4,16–18).

Notably, eIF6 is located in the nucleolus of certain cell lines,

such as HeLa, A431, NIH/3T3 fibroblasts and Jurkat T cells

(8), in addition to neoplastic

tissues, including colonic adenoma and carcinoma (6). Previous studies have demonstrated that

eIF6 functions as a component of the preribosomal particles in the

nucleolus, thus serving an important role in 60S ribosome

biogenesis (8,18). In the cytoplasm, eIF6 functions as a

translation factor (9), therefore,

subcellular localization is crucial for the functional regulation

of eIF6.

Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of

eIF6

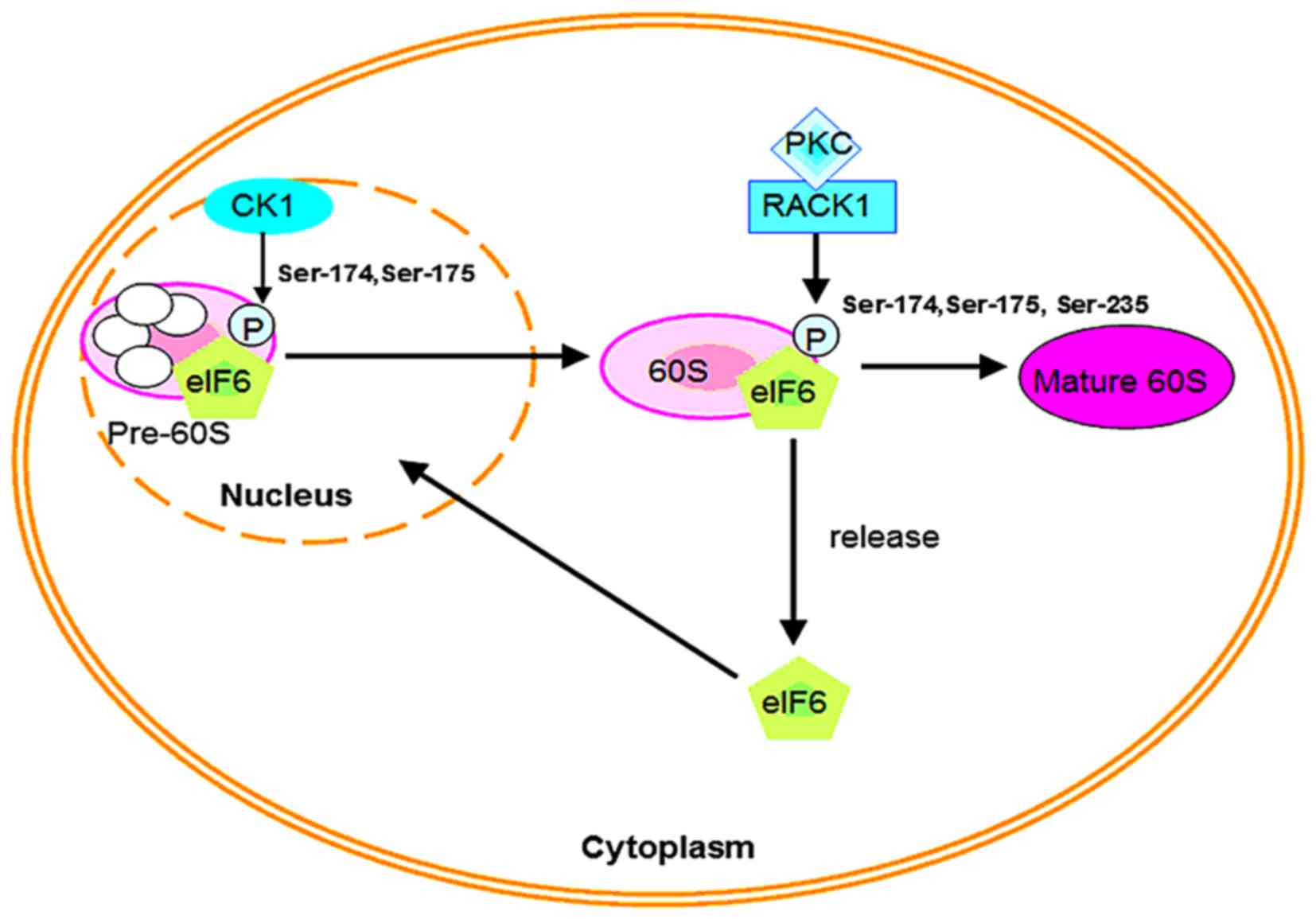

In mammalian cells, eIF6 regulates ribosomal

assembly and biogenesis, thus controlling the binding of 40S and

60S ribosomal subunits and participating in 80S assembly (7–9,16). As described above, eIF6 is present in

the nucleus and cytoplasm (9,17). Notably, it is reported that

nucleocytoplasmic shuttling is caused by the phosphorylation of

eIF6, in line with the well-established hypothesis that

phosphorylation is able to regulate the biological activity of

numerous proteins (9). Therefore,

phosphorylation is likely to modulate eIF6 activity, and three

potential phosphorylation sites have been identified (18). For nuclear export in mammalian cells,

eIF6 is phosphorylated in vitro at Ser-175 and Ser-174 by

the nuclear isoforms of casein kinase (CK) CK1α or CK1δ, thereby

promoting the formation of pre-60S ribosomal particles in the

cytoplasm. In addition, the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent

protein phosphatase calcineurin mediates dephosphorylation, which

facilitates migration of eIF6 back to the nucleolus and continues

60S ribosome biogenesis (18). Such

evidence implies that CK1 controls the subcellular distribution of

eIF6.

Although CK1 is widely found in the nucleus,

cytoplasm, cell membrane and cytoskeleton of mammalian and yeast

cells (19–21), it is unclear whether extranuclear CK1

enters the nucleus to regulate the export of eIF6. It should be

noted that cytoplasmic eIF6 in mammalian cells is also

phosphorylated by receptors for activated C kinase 1

(RACK1)/protein kinase C (PKC) signaling at positions Ser-174,

Ser-175 and Ser-235 (Fig. 1)

(16,22). These procedures result in dissociation

of eIF6 from the 60S subunit, thus aiding its maturation (18). Recent research demonstrates that

GTPase elongation factor-like 1 (EFL1) is involved in the

cytoplasmic maturation of the ribosomal 60S subunit (3). SBDS, the protein mutated in

Shwachman-Bodian-Diamond syndrome, and EFL1 release the

anti-association factor eIF6 from the surface of the 60S subunit

(2,5).

In addition, the Ser235 PKC phosphorylation site has also been

identified in the Xenopus eIF6 protein (23).

However, there is little or no evidence to verify

whether CK1 and the RACK1-PKC complex phosphorylate the Ser-174 and

Ser-175 sites of eIF6 at the same time. Moreover, an increasing

number of studies have demonstrated that eIF6 is highly

overexpressed in tumor cells (8–11). The

C-terminal of eIF6 is subject to RACK1-PKCβII complex

phosphorylation at Ser-235, which modulates the protumorigenic

activity of eIF6 (16), whereas

mutation of the phosphorylation site at Ser235 of eIF6 in mouse

models reduces translation and lymphomagenesis (4). A previous study demonstrated that the

Ras cascade, which regulates phosphorylation of eIF6, is triggered

by agonists of phorbol esters (16).

Therefore, it may be speculated that the Ras cascade recruits

PKCβII and phosphorylates eIF6 at Ser235, and the activity of eIF6

leads to increased translation and tumorigenesis.

Overexpression of eIF6 in human

carcinoma

Numerous studies have demonstrated highly aberrant

expression of eIF6 in human cancer (10–15).

Although the function of eIF6 is not fully understood, differential

expression of eIF6 is correlated with cancer pathogenesis, and eIF6

functions as a regulator in cancer development (6,10–15). The cancer tissues and cell lines in

which eIF6 is overexpressed are presented in Table I. In this section, the potential of

eIF6 as a cancer biomarker is discussed.

| Table I.Overexpression of eIF6 in various

cancer tissues and cell lines. |

Table I.

Overexpression of eIF6 in various

cancer tissues and cell lines.

| Type | Overexpression of

eIF6 |

|---|

| Cancer tissues | Colorectal cancer,

head and neck carcinoma, NSCLC, ovarian serous adenocarcinoma |

| Cancer cell

lines | A2780 ovarian

cancer cells, WM793 primary melanoma cells, SW480 colorectal cancer

cells |

Colorectal cancer

eIF6 is regarded as a nuclear matrix protein that

accumulates in nucleoli (8), and is

found in the cytoplasm of glandular crypt cells in the human

colonic epithelium (6). However,

higher levels of eIF6 are observed in colorectal carcinoma compared

with colorectal precancer and normal mucosa (6–7,16). Consequently, there is a progressive

increase of eIF6 from normal tissue to dysplastic adenoma and

carcinoma. This raises the question of which mechanisms are

involved in the increased expression of eIF6 protein. It is

hypothesized that eIF6 is upregulated at the transcriptional level,

such that the mRNA coding for eIF6 is highly concentrated in tumors

relative to normal colorectal tissues (6). mRNA translation controls distinct

cellular processes, including tumorigenesis, cell migration,

adhesion and growth, and cell-cycle control (24). Notably, gross gene expression of eIF6

is less well known. Therefore, further research is required to

understand the underlying reasons for this.

As a marker of cell proliferation, the distribution

of argyrophilic nucleolar organizer region (AgNOR)-associated

proteins in the nucleolus and cell correspond to proteins located

in the nucleolar organizer regions. Previously, nucleolar staining

by AgNORs was considered to be a prognostic marker of malignancy

(25). Moreover, the value of AgNORs

as proliferation markers has been reported in various forms of

cancer, such as breast, ovarian, cervical, prostate,

hepatocellular, papillary thyroid, gastric and bladder cancer

(25–31). Certain studies have demonstrated a

correlation between AgNOR count in tumors and various clinical

parameters, including tumor size and staging, and distant

metastasis (28–32). Therefore, eIF6 may be used as a

diagnostic tool on the basis of the function of AgNORs. In

addition, differentially-expressed eIF6 may serve a critical

function in colon carcinogenesis and provide a novel marker in

surgical pathology.

Head and neck carcinoma

eIF6 is overexpressed in colorectal cancer (6). Similarly, in head and neck carcinoma,

the expression of eIF6 is also higher than that observed in normal

mucosa (13). Additionally, nucleolar

overexpression of eIF6 has been detected in head and neck

metastatic carcinoma (13). Head and

neck cancer has previously been reported as the sixth leading type

of cancer worldwide, accounting for ~6% of all tumors, of which

>90% are head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (33,34).

Despite advances in treatment, the prognosis remains poor.

Therefore, the discovery of molecular markers is not only important

for understanding the pathogenesis of head and neck cancer, but may

also provide further insight into tumor biology, diagnosis,

therapeutic perspectives and prognosis (34,35).

eIF6 is highly concentrated in nucleoli, is easily

observed and its overexpression is not difficult to measure. eIF6

may function as a molecular marker for use in surgical pathological

diagnosis. Notably, a larger 52-kDa protein, detected by eIF6

antibody, is also observed in lymph node metastases (13). This larger protein has tissue

specificity due to its absence in samples of colorectal carcinoma,

parotid gland adenocarcinoma and leiomyosarcoma of the larynx

(13). Consequently, this 52-kDa band

is able to be utilized by head and neck surgeons and surgical

pathologists during diagnosis.

Non-small cell lung cancer

(NSCLC)

Lung cancer is an extraordinarily malignant tumor

with the highest morbidity and mortality, of which the most common

variant is NSCLC (36,37). The primary features of this cancer are

invasion and metastasis (36–39). eIF6 interacts with the cytoplasmic

integrin β4 subunit, and in a previous study, positive eIF6

staining was observed in 82.5% (66/80) of NSCLC specimens (37). Therefore, eIF6 is likely to be present

at a high concentration in NSCLC (6,13).

Integrin β4 subunit, α6β4, the receptor for the basement membrane

protein laminin-5, is an important cellular adhesion molecule, and

is closely associated with tumor invasion and metastasis (6,40). α6β4

integrin is expressed in invasive breast carcinomas and is a

potential indicator of poor prognosis (40). Taken together, a large increase in

eIF6 is apparent in NSCLC, which may promote the migration of NSCLC

cells; however, further study is required to confirm this.

Ovarian serous adenocarcinoma

Ovarian serous adenocarcinoma is the most prevalent

form of epithelial ovarian cancer and a fatal type of gynecological

malignancy (41,42). Human eIF6 is located on chromosome

20q12, which is an amplified chromosomal region (20q12-12) in

ovarian cancer (43). This suggests

that increased eIF6 may be a consequence of increased protein

turnover in rapidly proliferating malignant cells based upon its

role in ribosome assembly. Notably, eIF6, Dicer and RNaseIII

endonuclease, which are essential components of miRNA machinery,

are overexpressed in ovarian serous adenocarcinoma and associated

with its clinicopathological features (15). miRNAs are a class of small, noncoding

RNAs that affect the post-transcriptional control of mRNA and

contribute to human tumorigenesis (44–46). Low

eIF6 expression has increasingly been associated with reduced the

probability of disease-free survival (15). Therefore, it is not inconceivable that

downregulated expression of miRNAs and eIF6 could be useful

biomarkers for the prediction of ovarian serous adenocarcinoma.

Additionally, eIF6 and proteins of the miRNA machinery are closely

related to future RNA interference-based therapy.

Upstream modulator of eIF6

As aforementioned, eIF6 is overexpressed in human

colorectal cancer (6), head and neck

cancer (13), lung cancer (14) and ovarian serous adenocarcinoma

(15). Therefore, it is necessary to

determine which oncogenes in the transcriptional network control

eIF6 expression during tumorigenesis. Previous studies have

established that the transcription factor complex GA-binding

protein (GABP) regulates eIF6 expression, as the eIF6 promoter

region contains GABP-binding sites (47). GABP is an E26 transformation-specific

sequence (ETS) transcription factor, which contains an unrelated

GABP protein, an ETS DNA-binding domain and a nuclear localization

signal (48). The transcription of

nuclear genes involved in mitochondrial respiration is controlled

by the GABP complex (48). Moreover,

certain ribosomal proteins are also GABP targets (49,50). For

these reasons, GABP may be essential in regulating the

transcription of ribosomal genes. The activity of the eIF6 promoter

could be inhibited through blocking endogenous GABP activity. To

date, a possible function for GABP in tumorigenesis remains to be

described. Accounting for the fact that GABP could be vital in

mediating the proliferative response, it may be useful to determine

whether certain oncogenes directly affect GABP expression.

It is worth noting that the Notch-1 receptor has

been demonstrated to directly regulate transcription of the eIF6

gene (12). The Notch-1 receptor

belongs to the Notch family of transmembrane proteins in mammals

(51). The highly-conserved Notch

signaling pathway is essential in the regulation of various

physiological processes, including cell development,

differentiation and proliferation (52–55). In

particular, activation of the canonical Notch-1 pathway is of major

significance in human tumorigenesis (12,51,56). A

high level of Notch-1 expression has been observed in salivary

adenoid cystic carcinoma (56) and

breast cancer (57). Notably, it was

reported that Notch-1 activation resulted in a 2 to 3-fold

overexpression of eIF6, thus enhancing the invasiveness of A2780

cells (12,57). Therefore, it is conceivable that the

Notch-1 signal is key to control the expression of eIF6. Notch-1

functions as an upstream regulator of eIF6, which directly

regulates eIF6 expression via a recombinant binding protein

suppressor of Hairless (RBP-Jκ)-dependent mechanism. In other

words, the Notch-1/RBP-Jκ signaling pathway stimulates eIF6

promoter activity, resulting in abnormal expression of eIF6

(57,12). Overexpression of eIF6 enhances cell

migration and invasiveness, but it is noteworthy that it does not

affect proliferation (12).

Downstream regulation of eIF6

eIF6 and the canonical Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway

In previous studies, eIF6 has primarily been used to

control translation through regulation of ribosome biogenesis and

assembly (3,4,9,18). Further research using yeast two-hybrid

assays has demonstrated that eIF6 interacts with the C terminus of

β-catenin, functioning as a transcriptional activation domain

(7,55). In addition, the Wnt signal

transduction cascade, with β-catenin as a major transducer, is a

canonical cellular pathway in cell adhesion and proliferation

during embryogenesis in animals (58–61). In

general, the Wnt signal is absent in normal cells or tissues.

However, the aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling leads

to the dysregulation of cellular growth and development, and

contributes to human tumorigenesis (58,60). The

targets of β-catenin transcription are also overexpressed in

various types of carcinoma (59,63).

Although the molecular mechanism remains to be clarified, previous

research has demonstrated that dysregulation of Wnt/β-catenin

signaling results in large accumulation of β-catenin in the nucleus

(62,63). Subsequently, combined with T cell

factor/lymphoid enhancing factor (TCF/LEF), transcription of target

genes, including c-Myc (64) and

cyclin D1 (65), may be activated

resulting in carcinogenesis. Previous research has demonstrated

that eIF6 serves as a factor participating in Wnt/β-catenin

signaling and the distribution of eIF6 and β4 is altered in colonic

adenoma and carcinoma (6).

Furthermore, in SW480 cells transfected with full-length eIF6, the

level of activated β-catenin was reduced compared with controls

(66). The question may therefore be

raised as to whether eIF6 has the same effect as Dickkopf

antagonists on the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. However, this

is problematic to answer as eIF6 is overexpressed in colorectal

carcinoma (6). Moreover, MG132, a

proteasome-specific inhibitor, fails to inhibit the decrease in

β-catenin that occurs upon overexpression of yellow fluorescent

protein-eIF6 in SW480 cells (66).

Consequently, despite the fact that β-catenin functions as a

downstream effector of eIF6, eIF6 expression does not directly

regulate the level of β-catenin, indicating that downregulation of

β-catenin may only exist in certain vectors transfected with cell

lines overexpressing eIF6.

Downstream effector of eIF6: Cell

division control protein 42 (Cdc42)

In a previous study, several membrane-associated

proteins differed in abundance upon eIF6 overexpression in A2780

ovarian cancer cells (11). This

effect is particularly notable in Cdc42 (11), a small GTPase belonging to the Ras

homolog family (67–69). A number of studies have established

that Cdc42 regulates cell differentiation, cell cycle progression,

cell polarity, cell fate determination, and cell motility and

adhesion (68,70). Aberrant expression of Cdc42 is pivotal

in tumorigenesis, including that of breast carcinoma (71). Notably, it was reported that Cdc42

expression is disrupted at the post-transcriptional level by

enhanced levels of eIF6 in A2780 ovarian cancer cells (11). In addition, it was observed that

downstream of eIF6 activation, Cdc42 levels are increased by a

post-transcriptional mechanism (11).

Although the underlying mechanisms of eIF6-mediated

Cdc42 expression remain to be elucidated, a possible theory may be

that enhanced levels of eIF6 indirectly control the variation in

the abundance of Cdc42. This is supported by the fact that Cdc42

mRNA expression levels exhibit little or no difference following

eIF6 overexpression (11), which also

demonstrates that eIF6 may target the translation of specific

mRNAs. In A2780 cells overexpressing eIF6, ML-141, a selective and

potent inhibitor of Cdc42 GTPase, has been demonstrated to

significantly decrease migratory activity (11). The tumor-promoting ability of eIF6 is

not restricted to the A2780 cell line; the primary melanoma cell

line WM793 has also been reported to exhibit upregulated Cdc42

expression, in addition to increased motility and invasiveness

(11). Therefore, eIF6 is crucial for

Cdc42 upregulation. As eIF6 affects Cdc42 translation in ovarian

cancer cells, this indicates that the increased expression of eIF6

is more likely to cause Cdc42 activation in ovarian cancer tissue,

which in turn is accountable for increased migration and invasion.

Nevertheless, further studies are required to elucidate the

mechanisms behind these processes.

Conclusions and perspectives

The protein eIF6 possesses a high degree of

evolutionary sequence conservation (1–8), and is

located subcellularly in the nucleolus and cytoplasm.

Phosphorylation of eIF6 regulates nucleocytoplasmic shuttling in

mammalian cells and involves the release of eIF6 from the 60S

ribosome subunit (3,16,17). In

cancer cells, eIF6 is phosphorylated by the RACK1-PKCβII complex,

and thus by the Ras cascade (16,72). eIF6

functions as an important component in gene regulatory networks and

exerts crucial roles in neoplastic progression (10–15).

Nevertheless, the specific molecular mechanisms underlying the role

of eIF6 in these processes remain unclear. Oncogenesis typically

involves several different signaling pathways. For example, the

Ras-extracellular related kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase

pathway and phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT/mammalian target of

rapamycin pathway each take part in the phosphorylation of eIF4E,

which is involved in cancer development (73–75).

Consequently, it is possible that these signals are involved in the

mechanisms of eIF6 overexpression in cancer, since eIF4E is a

eukaryotic initiation factor in addition to eIF6.

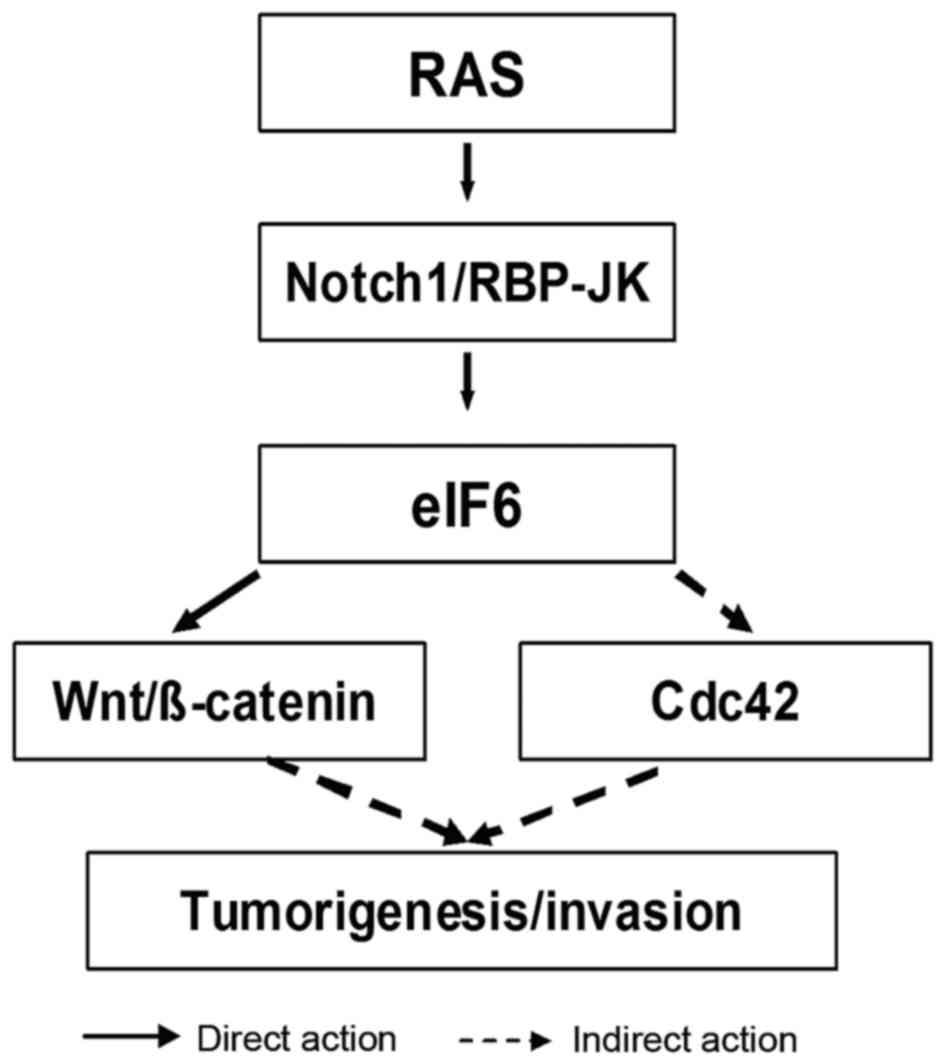

In conclusion, the following hypothesis is proposed

(Fig. 2). Firstly, Notch-1 activated

by oncogenic Ras promotes transcription of the eIF6 gene through an

RBP-Jκ-dependent mechanism. Ras signaling has a key role in

increasing Notch-1 expression in breast carcinoma (75). Secondly, overexpression of eIF6 leads

to aberrant activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

Similarly, overexpressed eIF6 controls its downstream effector

Cdc42, which in turn affects tumorigenesis. As a consequence,

understanding the signaling network in which eIF6 lies may

contribute novel insights into the pathogenesis of cancer, and

offer a promising target for the development of novel

antineoplastic agents.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the National

Natural Science Foundation of China, (grant no. 81472275) and the

Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (grant no.

2014A030313542).

References

|

1

|

Russell DW and Spremulli LL: Mechanism of

action of the wheat germ ribosome dissociation factor: Interaction

with the 60 S subunit. Arch Biochem Biophys. 201:518–526. 1980.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Finch AJ, Hilcenko C, Basse N, Drynan LF,

Goyenechea B, Menne TF, González Fernández A, Simpson P, D'Santos

CS, Arends MJ, et al: Uncoupling of GTP hydrolysis from eIF6

release on the ribosome causes Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Genes

Dev. 25:917–929. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Gartmann M, Blau M, Armache JP, Mielke T,

Topf M and Beckmann R: Mechanism of eIF6-mediated inhibition of

ribosomal subunit joining. J Biol Chem. 285:14848–14851. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Miluzio A, Beugnet A, Grosso S, Brina D,

Mancino M, Campaner S, Amati B, de Marco A and Biffo S: Impairment

of cytoplasmic eIF6 activity restricts lymphomagenesis and tumor

progression without affecting normal growth. Cancer Cell.

19:765–775. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

García-Márquez A, Gijsbers A, de la Mora E

and Sánchez-Puig N: Defective guanine nucleotide exchange in the

Elongation Factor-Like 1 (EFL1) GTPase by mutations in the

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome protein. J Biol Chem. 290:17669–17678.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sanvito F, Vivoli F, Gambini S,

Santambrogio G, Catena M, Viale E, Veglia F, Donadini A, Biffo S

and Marchisio PC: Expression of a highly conserved protein, p27BBP,

during the progression of human colorectal cancer. Cancer Res.

60:510–516. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Biffo S, Sanvito F, Costa S, Preve L,

Pignatelli R, Spinardi L and Marchisio PC: Isolation of a novel

beta4 integrin-binding protein (p27 (BBP)) highly expressed in

epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 272:30314–30321. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sanvito F, Piatti S, Villa A, Bossi M,

Lucchini G, Marchisio PC and Biffo S: The beta4 integrin interactor

p27 (BBP/eIF6) is an essential nuclear matrix protein involved in

60S ribosomal subunit assembly. J Cell Biol. 144:823–837. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gandin V, Miluzio A, Barbieri AM, Beugnet

A, Kiyokawa H, Marchisio PC and Biffo S: Eukaryotic initiation

factor 6 is rate-limiting in translation, growth and

transformation. Nature. 455:684–688. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Brina D, Grosso S, Miluzio A and Biffo S:

Translational control by 80S formation and 60S availability: The

central role of eIF6, a rate limiting factor in cell cycle

progression and tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 10:3441–3446. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pinzaglia M, Montaldo C, Polinari D,

Simone M, La Teana A, Tripodi M, Mancone C, Londei P and Benelli D:

EIF6 over-expression increases the motility and invasiveness of

cancer cells by modulating the expression of a critical subset of

membrane-bound proteins. BMC Cancer. 15:1312015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Benelli D, Cialfi S, Pinzaglia M, Talora C

and Londei P: The translation factor eIF6 is a Notch-dependent

regulator of cell migration and invasion. PLos One. 7:e320472012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rosso P, Cortesina G, Sanvito F, Donadini

A, Di Benedetto B, Biffo S and Marchisio PC: Overexpression of

p27BBP in head and neck carcinomas and their lymph node metastases.

Head Neck. 26:408–417. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Tang CL, Yuan SZ, Yang HP, Wang QL and

Zhang R: Expression and significance of P311 and ITGB4BP in

non-small lung cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 32:526–528.

2010.(In Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Flavin RJ, Smyth PC, Finn SP, Laios A,

O'Toole SA, Barrett C, Ring M, Denning KM, Li J, Aherne ST, et al:

Altered eIF6 and Dicer expression is associated with

clinicopathological features in ovarian serous carcinoma patients.

Mod Pathol. 21:676–684. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ceci M, Gaviraghi C, Gorrini C, Sala LA,

Offenhäuser N, Marchisio PC and Biffo S: Release of eIF6 (p27BBP)

from the 60S subunit allows 80S ribosome assembly. Nature.

426:579–584. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Biswas A, Mukherjee S, Das S, Shields D,

Chow CW and Maitra U: Opposing action of casein kinase 1 and

calcineurin in nucleo-cytoplasmic shuttling of mammalian

translation initiation factor eIF6. J Biol Chem. 286:3129–3138.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Miluzio A, Beugnet A, Volta V and Biffo S:

Eukaryotic initiation factor 6 mediates a continuum between 60S

ribosome biogenesis and translation. EMBO Rep. 10:459–465. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Cruciat CM: Casein kinase 1 and

Wnt/b-catenin signaling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 31:46–55. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Schittek B and Sinnberg T: Biological

functions of casein kinase 1 isoforms and putative role in

tumorigenesis. Mol Cancer. 13:2312014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Knippschild U, Kruger M, Richter J, Xu P,

García-Reyes B, Peifer C, Halekotte J, Bakulev V and Bischof J: The

CK1 family: Contribution to cellular stress response and its role

in carcinogenesis. Front Oncol. 4:962014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

de Marco N, Iannone L, Carotenuto R, Biffo

S, Vitale A and Campanella C: p27 (BBP)/eIF6 acts as an

anti-apoptotic factor upstream of Bcl-2 during Xenopus laevis

development. Cell Death Differ. 17:360–372. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

de Marco N, Tussellino M, Vitale A and

Campanella C: Eukaryotic initiation factor 6 (eif6) overexpression

affects eye development in Xenopus laevis. Differentiation.

82:108–115. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Silvera D, Formenti SC and Schneider RJ:

Translational control in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 10:254–266. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Atallah AM, Tabll AA, El-Nashar E,

El-Bakry KA, El-Sadany M, Ibrahim T and El-Dosoky I: AgNORs count

and DNA ploidy in liver biopsies from patients with schistosomal

liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Biochem.

42:1616–1620. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Gottwald L, Danilewic M, Fendler W, Suzin

J, Spych M, Piekarski J, Tylinski W, Chalubinska J,

Topczewska-Tylinska K and Cialkowska-Rysz A: The AgNORs count in

predicting long-term survival in serous ovarian cancer. Arch Med

Sci. 10:84–90. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Lewinska A, Adamczyk J, Pajak J, Stoklosa

S, Kubis B, Pastuszek P, Slota E and Wnuk M: Curcumin-mediated

decrease in the expression of nucleolar organizer regions in

cervical cancer (HeLa) cells. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ

Mutagen. 771:43–52. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Winzer KJ, Bellach J and Hufnagl P:

Long-term analysis to objectify the tumour grading by means of

automated microscopic image analysis of the nucleolar organizer

regions (AgNORs) in the case of breast carcinoma. Diagn Pathol.

8:562013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gupta V, Garg M, Chaudhry M, Singh S, Sen

R, Gill M and Sangwaiya A: Role of cyclin D1 immunoreactivity and

AgNOR staining in the evaluation of benign and malignant lesions of

the prostate. Prostate Int. 2:90–96. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Raĭkhlin NT, Bukaeva IA, Smirnova EA,

Pavlovskaia AI, Brzhezovskiĭ VZh, Bogatyrev VN and Ponomareva MV:

Prognistic value of a study of the expression of argyrophilic

nucleolar organizer region associated proteins in case of papillary

thyroid cancer. Arkh Patol. 72:49–52. 2010.(In Russian). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mondal NK, Roychoudhury S and Ray MR:

Higher AgNOR expression in metaplastic and dysplastic airway

epithelial cells predicts the risk of developing lung cancer in

women chronically exposed to biomass smoke. J Environ Pathol

Toxicol Oncol. 34:35–51. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Alaeddini M, Khalili M, Tirgary F and

Etemad-Moghadam S: Argyrophylic proteins of nucleolar organizer

regions (AgNORs) in salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma and its

relation to histological grade. Oral Surg Oral Pathol Oral Radiol

Endod. 105:758–762. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Duvvuri U and Myers JN: Cancer of the head

and neck is the sixth most common cancer worldwide. Curr Probl

Surg. 46:114–117. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ and Brakenhoff

RH: The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

11:9–22. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ferreira MB, De Souza JA and Cohen EE:

Role of molecular markers in the management of head and neck

cancers. Curr Opin Oncol. 23:259–264. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Siegel R, Naishadham D and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 63:11–30. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Peters S, Adjei AA, Gridelli C, Reck M,

Kerr K and Felip E; ESMO Guidelines Working Group, : Metastatic

non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): ESMO Clinical Practice

Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol.

23:vii56–vii64. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Cetin K, Ettinger DS, Hei YJ and O'Malley

CD: Survival by histologic subtype in stage IV nonsmall cell lung

cancer based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End

Results Program. Clin Epidemiol. 3:139–48. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Zhang J, Zhang J, Cui X, Yang Y, Li M, Qu

J, Li J and Wang J: FoxM1: A novel tumor biomarker of lung cancer.

Int J Clin Exp Med. 8:3136–3140. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Diaz LK, Zhou X, Welch K, Sahin A and

Gilcrease MZ: Chromogenic in situ hybridization for alpha6beta4

integrin in breast cancer: Correlation with protein expression. J

Mol Diagn. 6:10–15. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 65:5–29. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Karlsen MA, Høgdall EV, Christensen IJ,

Borgfeldt C, Kalapotharakos G, Zdrazilova-Dubska L, Chovanec J, Lok

CA, Stiekema A, Mutz-Dehbalaie I, et al: A novel diagnostic index

combining HE4, CA125 and age may improve triage of women with

suspected ovarian cancer-An international multicenter study in

women with an ovarian mass. Gynecol Oncol. 138:640–646. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tanner MM, Grenman S, Koul A, Johannsson

O, Meltzer P, Pejovic T, Borg A and Isola JJ: Frequent

amplification of chromosomal region 20q12-q13 in ovarian cancer.

Clin Cancer Res. 6:1833–1839. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Katz B, Tropé CG, Reich R and Davidson B:

MicroRNAs in ovarian cancer. Hum Pathol. 46:1245–1256. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

van Jaarsveld MT, Helleman J, Berns EM and

Wiemer EA: MicroRNAs in ovarian cancer biology and therapy

resistance. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 42:1282–1290. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Chong GO, Jeon HS, Han HS, Son JW, Lee YH,

Hong DG, Lee YS and Cho YL: Differential microRNA expression

profiles in primary and recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer.

Anticancer Res. 35:2611–2617. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Donadini A, Giacopelli F, Ravazzolo R,

Gandin V, Marchisio PC and Biffo S: GABP complex regulates

transcription of eIF6 (p27BBP), an essential trans-acting factor in

ribosome biogenesis. FEBS Lett. 580:1983–1987. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Ristevski S, O'Leary DA, Thornell AP, Owen

MJ, Kola I and Hertzog PJ: The ETS transcription factor GABPalpha

is essential for early embryogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 24:5844–5849.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Ristola M, Arpiainen S, Shimokawa T, Ra C,

Tienari J, Saleem MA, Holthöfer H and Lehtonen S: Regulation of

nephrin gene by the Ets transcription factor, GA-binding protein.

Nephrol Dial Transplant. 28:846–855. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Yu S, Cui K, Jothi R, Zhao DM, Jing X,

Zhao K and Xue HH: GABP controls a critical transcription

regulatory module that is essential for maintenance and

differentiation of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. Blood.

117:2166–2178. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD and Lake RJ:

Notch signaling: Cell fate control and intergration in development.

Science. 284:770–776. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Radtke F, MacDonald HR and

Tacchini-Cottier F: Regulation of innate andadaptive immunity by

Notch. Nat Rev Immunol. 13:427–437. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Ranganathan P, Weaver KL and Capobianco

AJ: Notch signalling in solid tumours: A little bit of everything

but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 11:338–351. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Lin JT, Chen MK, Yeh KT, Chang CS, Chang

TH, Lin CY, Wu YC, Su BW, Lee KD and Chang PJ: Association of high

levels of Jagged-1 and Notch-1 expression with poor prognosis in

head and neck cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 17:2976–2983. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Ranganathan P, Weaver KL and Capobianco

AJ: Notch signalling in solid tumours: A little bit of everything

but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 11:338–351. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Bell D, Hanna EY, Miele L, Roberts D,

Weber RS and El-Naggar AK: Expression and significance of notch

signaling pathway in salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma. Ann Diagn

Pathol. 18:10–13. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zardawi SJ, Zardawi I, McNeil CM, Millar

EK, McLeod D, Morey AL, Crea P, Murphy NC, Pinese M, Lopez-Knowles

E, et al: High Notch1 protein expression is an early event in

breast cancer development and is associated with the HER-2

molecular subtype. Histopathology. 56:286–296. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Arya M, Thrasivoulou C, Henrique R, Millar

M, Hamblin R, Davda R, Aare K, Masters JR, Thomson C, Muneer A, et

al: Targets of Wnt/ß-catenin transcription in penile carcinoma.

PLos One. 10:e01243952015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Clevers H and Nusse R: Wnt/b-catenin

signaling and disease. Cell. 149:1192–1205. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Polakis P: Drugging Wnt signaling in

cancer. EMBO J. 31:2737–2746. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Li VS, Ng SS, Boersema PJ, Low TY,

Karthaus WR, Gerlach JP, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Maurice MM, Mahmoudi

T and Clevers H: Wnt signaling through inhibition of β-catenin

degradation in an intact Axin1 complex. Cell. 149:1245–1256. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Niehrs C and Acebron SP: Mitotic and

mitogenic Wnt signalling. EMBO J. 31:2705–2713. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Klaus A and Birchmeier W: Wnt signaling

and its impact on development and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer.

8:387–398. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Higgs MR, Lerat H and Pawlotsky JM:

Hepatitis C virus-induced activation of β-catenin promotes c-Myc

expression and a cascade of pro-carcinogenetic events. Oncogene.

32:4683–4693. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Wang H, Wang H, Makki MS, Wen J, Dai Y,

Shi Q, Liu Q, Zhou X and Wang J: Overexpression of β-catenin and

cyclinD1 predicts a poor prognosis in ovarian serous carcinomas.

Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 7:264–271. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ji Y, Shah S, Soanes K, Islam MN, Hoxter

B, Biffo S, Heslip T and Byers S: Eukaryoticinitiation factor 6

selectively regulates Wnt signaling and beta-catenin protein

synthesis. Oncogene. 27:755–762. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Sahai E and Marshall CJ: Rho GTPases and

cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2:133–142. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Pedersen E and Brakebusch C: Rho GTPase

function in development: How in vivo models change our view. Exp

Cell Res. 318:1779–1787. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Reymond N, Riou P and Ridley AJ: Rho

GTPases and cancer cell transendothelial migration. Methods Mol

Biol. 827:123–142. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Stengel K and Zheng Y: Cdc42 in oncogenic

transformation, invasion, and tumorigenesis. Cell Signal.

23:1415–1423. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Bray K, Gillette M, Young J, Loughran E,

Hwang M, Sears JC and Vargo-Gogola T: Cdc42 overexpression induces

hyperbranching in the developing mammary gland by enhancing cell

migration. Breast Cancer Res. 15:R912013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Weijzen S, Rizzo P, Braid M, Vaishnav R,

Jonkheer SM, Zlobin A, Osborne BA, Gottipati S, Aster JC, Hahn WC,

et al: Activation of Notch-1 signaling maintains the neoplastic

phenotype in human Ras-transformed cells. Nat Med. 8:979–986. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Furic L, Rong L, Larsson O, Koumakpayi IH,

Yoshida K, Brueschke A, Petroulakis E, Robichaud N, Pollak M,

Gaboury LA, et al: eIF4E phosphorylation promotes tumorigenesis and

is associated with prostate cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 107:pp. 14134–14139. 2010; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Cope CL, Gilley R, Balmanno K, Sale MJ,

Howarth KD, Hampson M, Smith PD, Guichard SM and Cook SJ:

Adaptation to mTOR kinase inhibitors by amplification of eIF4E to

maintain cap-dependent translation. J Cell Sci. 127:788–800. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Grosso S, Pesce E, Brina D, Beugnet A,

Loreni F and Biffo S: Sensitivity of global translation to mTOR

inhibition in REN cells depends on the equilibrium between eIF4E

and 4E-BP1. PLoS One. 6:e291362011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|