Introduction

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most

common type of malignant lymphoma in adults, accounting for 31% of

all non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) in western countries (1). DLBCL can be divided into two main

subtypes, germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) and activated

B-cell-like (non-GCB), based on evaluation of the cell of origin

using gene expression profiling (2).

Non-GCB DLBCL tends to have an inferior prognosis compared to GCB

DLBCL, with a 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate of 40%

compared to 75% in GCB DLBCL (3).

The combination chemotherapy regimen with

cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP)

plus rituximab (R-CHOP) is the new standard in first-line therapy

for DLBCL, which can significantly improve overall survival (OS) in

both GCB and non-GCB DLBCL. Previous studies have shown that 76% of

DLBCL patients acquire complete response (CR) with R-CHOP, while

~40% of patients will have an initial response followed by

refractory or relapsed disease and most of these patients will

eventually succumb to disease (4,5).

Therefore, researchers are studying the molecular biology and

genetics of tumor cells in order to discover novel biomarkers,

provide new therapeutic targets, and develop new ideas to improve

prognosis.

Myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MYD88) is

the first identified member of the Toll-interleukin-1 (IL-1)

receptor (TIR) family, an adaptor protein that mediates toll and

interleukin receptor signaling and activates nuclear factor-κB

(NF-κB) pathways (6). The

constitutive activation of NF-κB pathways is a distinguishing

feature of non-GCB DLBCL (7,8). Ngo et al identified that the

MYD88 signaling pathway is essential for the pathogenesis of

non-GCB DLBCL. Among mutations affecting this pathway, the

MYD88 L265P mutation is the most frequent and has the most

severe oncogenic effects through its alteration of NF-κB signaling

pathways (9). This mutation was

identified in 29% of non-GCB DLBCL but is rare in GCB DLBCL

(9).

To our best knowledge, there are seven studies

investigated the prognosis value of MYD88 L265P in DLBCL.

Three studies reported that the MYD88 L265P mutation was not

a significant prognostic indicator for DLBCL and primary breast

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (PBDLBCL) (10–12).

Nevertheless, the other four studies found that MYD88 L265P

mutation was associated with poor prognosis of DLBCL, primary

cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, and primary central

nervous system lymphoma (13–16). Researchers have not reached a

consensus regarding the role of MYD88 L265P as a prognostic

factor for this subset of DLBCL patients.

With the arrival of various targeted therapeutic

agents acting on NF-κB pathways, mutational analysis of a limited

number of genes in these pathways could help in selecting an

optimal treatment strategy in DLBCL (17,18). The

majority of non-GCB DLBCL patients treated with the R-CHOP regimen

have poor outcomes, which raises concerns regarding the

MYD88 L265P mutation. To the best of our knowledge, there

has been no analysis regarding the association between treatment

response to R-CHOP and the MYD88 L265P mutation in DLBCL

patients. Therefore, in our study we investigated the prevalence of

the MYD88 L265P mutation in patients with DLBCL and

evaluated its association with the response to R-CHOP and other

clinicopathologic characteristics, including patient outcome.

Materials and methods

Patients and sample collection

This study was retrospective in nature and included

53 patients who were newly diagnosed with DLBCL between January

2007 and January 2015 in the Sichuan Cancer Hospital based on the

current World Health Organization classifications (19). Inclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Available clinical and follow-up data; ii) CD20-positive; iii)

undergoing R-CHOP chemotherapy for at least 3 continuous cycles;

and iv) tumor samples available at diagnosis for DNA analysis.

Classification into the GCB/non-GCB subgroups by

immunohistochemistry followed the algorithm of Hans (20). Overall survival (OS) was defined as

the period from clear diagnosis to death, lost follow-up or

deadline. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the period

from clear diagnosis of the tumor to first tumor progression,

death, lost follow-up or deadline.

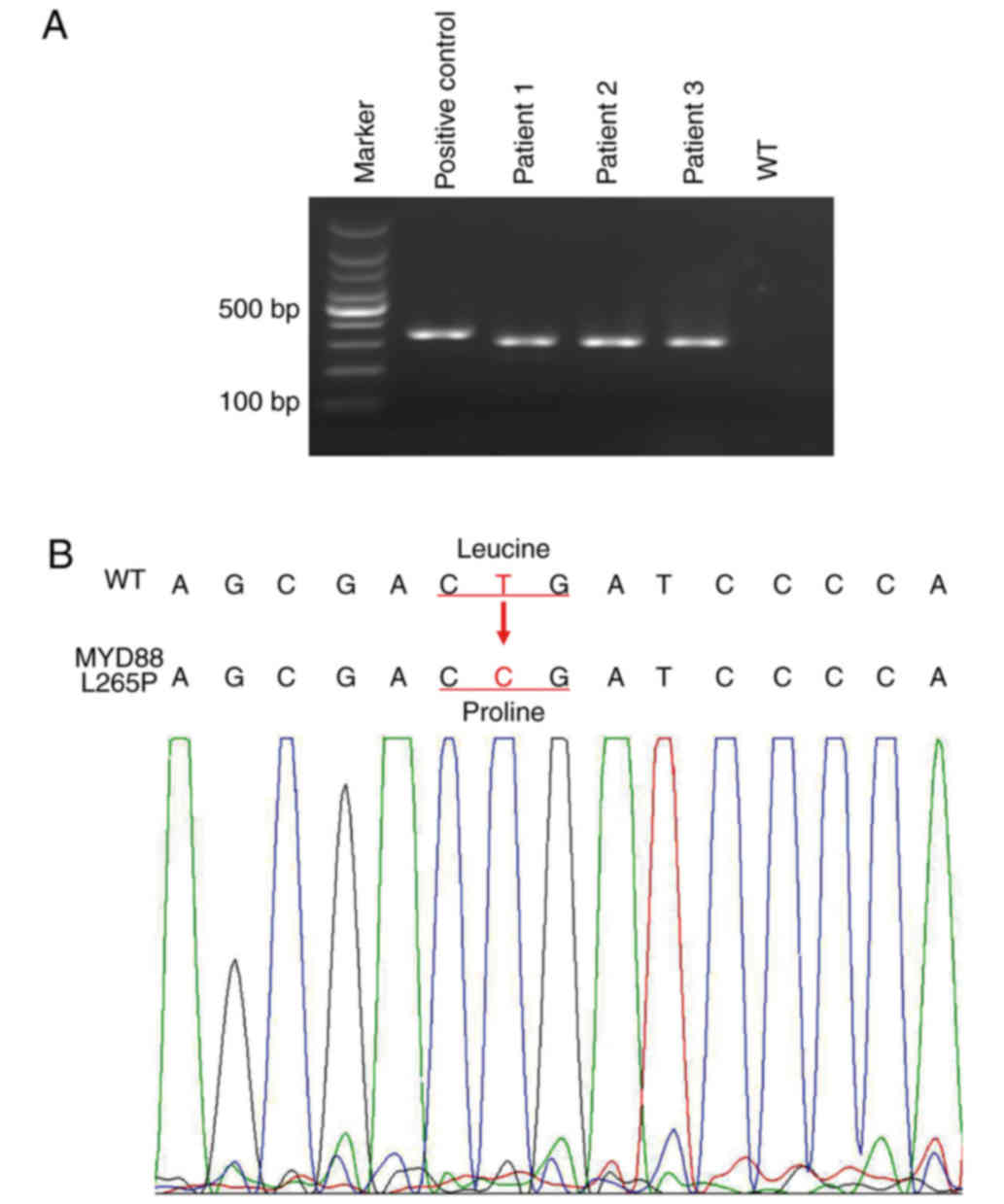

DNA was extracted from 4% formalin-fixed

paraffin-embedded tissues with the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit

(Qiagen, Ltd., Sussex, UK) following the manufacturer's

instructions. The L265P mutant of MYD88 was prepared by PCR

with site-directed mutagenic primers using DNA from a healthy

individual as a positive control, and the wild-type MYD88

allele from a healthy person was used as a reference (Table I). L265P mutant DNA and wild-type DNA

was validated by examination of agarose gels and Sanger sequencing

(Fig. 1). The standards for

MYD88 L265P were generated by a serial dilution of the

mutant DNA with the wild-type DNA (10−3,

10−4, 10−5, 10−6, 10−7,

10−8, 10−9, 10−10,

10−11, 10−12, 10−13). All primers

were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 (Premier Biosoft

International, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Primer synthesis and Sanger

sequencing were conducted by Tsingke (Chengdu, China).

| Table I.Primers of PCR in this study. |

Table I.

Primers of PCR in this study.

| Variable | Primers |

|---|

| Site-directed

mutagenesis primers (340 bp) | F:

5′-CAGCCTCTCTCCAGGTAAGCTCAACC-3′ |

|

| R:

5′-ATTGCCTTGTACTTGATGGGGATCGGTCGCTTCTG-3′ |

|

| (containing

mutation L265P base) |

| First round general

PCR (604 bp) | F:

5′-CAGCCTCTCTCCAGGTAAGCTCAACC-3′ |

|

| RW:

5′-ATTGCCTTGTACTTGATGGGGATCA-3′ |

|

| RM:

5′-CCTTGTACTTGATGGGGAAGG-3′ |

|

| (two internal

mismatches in the 2nd and 3rd position from the 3′-end) |

| Second real-time

PCR (304 bp) | F:

5′-GGCAAGAGAATGAGGGAATGTG-3′ |

|

| RW:

5′-GCCTTGTACTTGATGGGGAACA-3′ |

|

| RM:

5′-CCTTGTACTTGATGGGGAACG-3′ |

|

| (an internal

mismatch in the 3rd position from the 3′-end) |

The study was performed after patients signed

informed consent, and it was approved by the Ethics Committee of

the Sichuan Cancer Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of

Helsinki.

Development of allele-specific

semi-nested PCR (ASSN-PCR) assay for MYD88 L265P assessment

The ASSN-PCR method included two steps of PCR. The

first round was a conventional AS-PCR assay. We designed two

reverse primers to separate the mutant and wild-type alleles of

MYD88 L265P and one common primer to amplify large fragments

to improve the sensitivity of the ASSN-PCR. To increase the

specificity of the ASSN-PCR, we introduced two internal mismatches

in the second and third positions from the 3′-end in the reverse

primer (Table I) (21).

PCR was performed in a total reaction volume of 25

ml, including 50 nM of each primer, 15 ng DNA and 2X master mix

(Tsingke). Thermal cycling conditions consisted of the following:

Five minutes of preheating at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 sec

at 95°C, 45 sec at 56°C, and 1 min at 72°C. The final step was an

extension step for 5 min at 72°C.

The second round was a quantitative AS-(q)PCR assay

for the assessment of MYD88 L265P. After the first round of

conventional PCR, we obtained two PCR products for each specimen

(wild-type products, W; likely mutation products, M). To optimize

the real-time PCR, we diluted W and M to 10−8 and

10−4, respectively. Then, the second round of real-time

AS-PCR was developed using specific primers (Table I) with diluted W, diluted M and

standards as templates. Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix was applied

following the manufacturer's instructions and reactions were run on

the ABI Prism 7500 Sequence Detection system (Applied Biosystems,

Foster City, CA, USA). The contents of the PCR reactions were the

same as in the first round of AS-PCR. Thermal cycling conditions

were: Two minutes of preheating at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of

30 sec at 95°C, 45 sec at 62°C, and routine melt curve cycling

conditions. The products of the second round of real-time AS-PCR

were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Interpretation of AS-qPCR results

The CT (MYD88 L265P)

represents the amount of mutated MYD88 L265P within the

sample, while the CT (wild-type) reflects the

total amount of MYD88 allelic template in the sample.

ΔCT cut-off value was measured using the formula

below:

ΔCT=CT(MY88L265P)–CT(wild-type)ΔCTcut-off=CT(10–8)–CT(AR-W)

where CT (10−8) is the average

CT (MY88 L265P) value of the 10−8 dilution of

positive control template mixed into a normal DNA template, and

CT(AR-W) is the average CT(wild-type) value

of allelic reference.

A positive result for the MYD88 L265P

mutation is defined as a mean ΔCT value less than

ΔCT cut-off value for each sample, while a negative

mutation result (i.e., no mutation detected) is defined as a mean

ΔCT exceeding the ΔCT cut-off value.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS

version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). We used a Chi-square or

Fisher's exact test to analyze the association between categorical

variables and the MYD88 L265P mutation, and the Mann-Whitney

U test to evaluate the association between continuous variables and

the MYD88 L265P mutation. The association between

MYD88 L265P and patient survival (OS and PFS) was evaluated

by survival curves using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank

(Mantel-Cox test). Cox regression was applied to evaluate the

independent factors for OS and PFS. Two-sided P-value

<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Specificity and sensitivity of AS-qPCR

assay

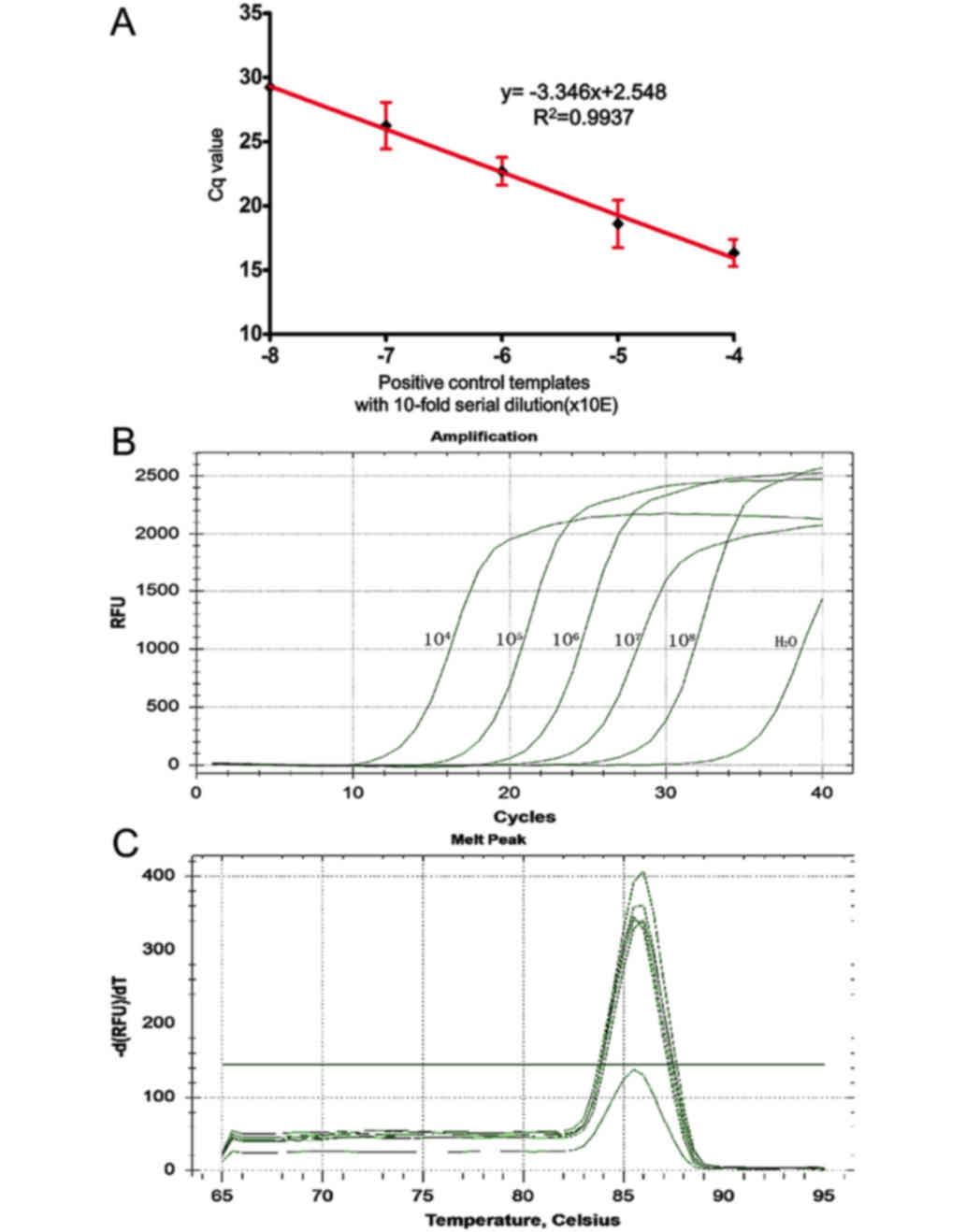

We analyzed the sensitivity and specificity of the

AS-qPCR assay in detecting the MYD88 L265P mutation using a

standard curve. The standard curve amplification plot and linear

regression (the standards diluted from 10−4 to

10−8) generated a correlation coefficient of 0.9937,

with a y-intercept value of 2.548 and a slope of −3.346. The

calculated amplification efficiency was 99% (Fig. 2A and B). This method was determined to

be suitable for the detection and quantitative assessment of

MYD88 L265P and is capable of detecting MYD88 L265P

at a lower limit of 10−12. Analysis of the melt curves

showed that the PCR assay had good specificity (Fig. 2C). ΔCT cut-off value has a

value of 6.01±0.076. Thus, the sample ΔCT value of all

mutant specimens for each assay ≤6 or >6 was interpreted as

positive or negative for the MYD88 L265P mutation,

respectively.

Correlation between MYD88 L265P status

and clinical characteristics

The clinicopathologic characteristics of the 53

DLBCL patients are listed in Table

II and associations between clinicopathologic factors and the

MYD88 mutation status are summarized in Table III. Among 53 DLBCL patients, 28

cases presented with extranodal invasion, and mutation statuses of

the DLBCL patients are listed in Table

IV. Using the ASSN-PCR assay, we detected the MYD88

L265P mutation in 16 out of 53 R-CHOP-treated DLBCL patients

(30.19%). The MYD88 L265P mutation rate in the central

nervous system (CNS) and testicular DLBCLs is 60% (3/5) (Table IV). Further, by excluding the CNS and

testicular DLBCLs, the MYD88 L265P mutation ratio is 27.08%

(13/48). We discovered that the MYD88 L265P mutation was not

statistically significantly associated with treatment response or

tumor recurrence (P>0.05). However, the MYD88 L265P

mutational status showed a significant association with age

(P=0.025) and location (P=0.033).

| Table II.Clinicopathologic characteristics of

DLBCL cases. |

Table II.

Clinicopathologic characteristics of

DLBCL cases.

| Clinicopathologic

parameters | No. of patients

(n=53) | Proportion (%) |

|---|

| Age (years) |

|

|

|

<60 | 32 | 56.604 |

|

≥60 | 21 | 43.396 |

| Sex |

|

|

|

Male | 31 | 58.491 |

|

Female | 22 | 41.509 |

| Location |

|

|

|

Nodal | 25 | 47.169 |

|

Extranodal | 28 | 52.831 |

| B symptom |

|

|

|

Absent | 41 | 77.358 |

|

Present | 12 | 22.642 |

| Clinical stage |

|

|

| Low

(I–II) | 26 | 49.057 |

| High

(III–IV) | 27 | 50.943 |

| Subgroup |

|

|

|

GCB | 11 | 20.755 |

|

Non-GCB | 42 | 79.245 |

| IPI score |

|

|

| Low

(0–2) | 35 | 66.038 |

| High

(3–5) | 18 | 33.962 |

| ECOG score |

|

|

| Low

(0–1) | 45 | 84.906 |

| High

(2–4) | 8 | 15.094 |

| LDH |

|

|

|

Normal | 24 | 45.283 |

|

High | 29 | 54.717 |

| Ki-67 |

|

|

|

≤50 | 42 | 79.25 |

|

>50 | 11 | 20.75 |

| Treatment

response |

|

|

|

CR/PR | 47 | 88.679 |

|

PD/SD | 6 | 11.321 |

| Recurrence |

|

|

|

Absent | 28 | 52.83 |

|

Present | 25 | 47.17 |

| Table III.The association analysis between

clinical characters and MYD88 mutation in DLBCL cases. |

Table III.

The association analysis between

clinical characters and MYD88 mutation in DLBCL cases.

|

|

| MYD88

mutation (%) |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinicopathologic

parameters | No. | WT | L265P | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) |

|

|

| 0.025 |

|

<60 | 32 | 26 (70.03) | 6 (37.5) |

|

|

≥60 | 21 | 11 (29.7) | 10 (62.5) |

|

| Sex |

|

|

| 0.828 |

|

Male | 31 | 22 (59.5) | 9 (56.2) |

|

|

Female | 22 | 15 (40.5) | 7 (43.8) |

|

| Location |

|

|

| 0.033 |

|

Nodal | 25 | 21 (56.8) | 4 (25.0) |

|

|

Extranodal | 28 | 16 (43.2) | 12 (75.0) |

|

| B symptom |

|

|

| 0.787 |

|

Absent | 41 | 29 (78.4) | 12 (75.0) |

|

|

Present | 12 | 8 (21.6) | 4 (25.0) |

|

| Clinical stage |

|

|

| 0.611 |

| Low

(I–II) | 26 | 19 (51.4) | 7 (43.8) |

|

| High

(III–IV) | 27 | 18 (48.6) | 9 (56.2) |

|

| Subgroup |

|

|

| 0.275 |

|

GCB | 11 | 6 (16.2) | 5 (31.2) |

|

|

Non-GCB | 42 | 31 (83.8) | 11 (68.8) |

|

| IPI score |

|

|

| 0.322 |

| Low

(0–2) | 35 | 26 (70.3) | 9 (56.2) |

|

| High

(3–5) | 18 | 11 (29.7) | 7 (43.8) |

|

| ECOG score |

|

|

| 0.729 |

| Low

(0–1) | 45 | 31 (83.8) | 14 (87.5) |

|

| High

(2–4) | 8 | 6 (16.2) | 2 (12.5) |

|

| LDH |

|

|

| 0.454 |

|

Normal | 24 | 18 (48.6) | 6 (37.5) |

|

|

High | 29 | 19 (51.4) | 10 (62.5) |

|

| Ki-67 |

|

|

| 0.632 |

|

<50 | 5 | 3 (8.1) | 2 (12.5) |

|

|

≥50 | 48 | 34 (91.1) | 14 (87.5) |

|

| Treatment

response |

|

|

| 0.655 |

|

CR/PR | 47 | 32 (86.5) | 15 (93.8) |

|

|

PD/SD | 6 | 5 (23.5) | 1 (6.2) |

|

| Recurrence |

|

|

| 0.743 |

|

Absent | 28 | 19 (51.4) | 9 (56.2) |

|

|

Present | 25 | 18 (48.6) | 7 (43.8) |

|

| Table IV.The mutation status of enrolled

patients. |

Table IV.

The mutation status of enrolled

patients.

| ID | MYD88 | Sex | Age (years) | Extranodal sites

(NO.; location) |

|---|

| 1 | Wide-type | Male | 60 | 1; testis |

| 2 | Wide-type | Female | 48 | 3; lung, liver,

bone marrow |

| 3 | Wide-type | Male | 68 | 0 |

| 4 | Wide-type | Male | 68 | 2; Liver, CNS |

| 5 | L265P | Male | 55 | 0 |

| 6 | Wide-type | Male | 48 | 2; Oropharynx,

stomach |

| 7 | Wide-type | Female | 58 | 1; Left frontal

lobe |

| 8 | Wide-type | Male | 26 | 0 |

| 9 | Wide-type | Female | 41 | 1; stomach |

| 10 | L265P | Female | 61 | 0 |

| 11 | L265P | Male | 70 | 1; testis |

| 12 | Wide-type | Male | 25 | 0 |

| 13 | L265P | Female | 62 | 3; Bone marrow,

iliac, calf skin |

| 14 | L265P | Female | 40 | 4; Breast, CNS,

spinal cord, pelvic cavity |

| 15 | Wide-type | Male | 61 | 1; thyroid |

| 16 | Wide-type | Female | 61 | 0 |

| 17 | Wide-type | Male | 27 | 1; stomach |

| 18 | Wide-type | Male | 78 | 1; bone |

| 19 | Wide-type | Female | 74 | 1; skin |

| 20 | Wide-type | Female | 79 | 1; thyroid |

| 21 | Wide-type | Male | 49 | 2; bone marrow,

bone |

| 22 | Wide-type | Female | 53 | 0 |

| 23 | L265P | Female | 46 | 1; Bone |

| 24 | Wide-type | Female | 32 | 1; Breast |

| 25 | Wide-type | Male | 73 | 0 |

| 26 | Wide-type | Female | 20 | 0 |

| 27 | Wide-type | Female | 56 | 2; Psoas muscle,

vertebral body |

| 28 | Wide-type | Female | 44 | 0 |

| 29 | L265P | Male | 57 | 1; lung |

| 30 | L265P | Male | 40 | 1; CNS |

| 31 | L265P | Male | 34 | 0 |

| 32 | Wide-type | Male | 56 | 0 |

| 33 | Wide-type | Male | 54 | 1; lung |

| 34 | L265P | Male | 67 | 0 |

| 35 | L265P | Male | 62 | 1; thyroid |

| 36 | Wide-type | Female | 53 | 0 |

| 37 | Wide-type | Male | 52 | 0 |

| 38 | Wide-type | Male | 64 | 0 |

| 39 | L265P | Female | 75 | 1; thyroid |

| 30 | L265P | Male | 63 | 1; lung |

| 41 | Wide-type | Male | 43 | 0 |

| 42 | Wide-type | Male | 75 | 0 |

| 43 | Wide-type | Female | 49 | 0 |

| 44 | Wide-type | Male | 47 | 0 |

| 45 | Wide-type | Female | 55 | 0 |

| 46 | Wide-type | Male | 66 | 0 |

| 47 | Wide-type | Female | 43 | 0 |

| 48 | L265P | Male | 72 | 1; stomach |

| 49 | Wide-type | Male | 60 | 0 |

| 50 | Wide-type | Male | 41 | 0 |

| 51 | L265P | Female | 66 | 1; thyroid |

| 52 | Wide-type | Male | 45 | 1; stomach |

| 53 | L265P | Female | 64 | 2; lung, bone |

MYD88 L265P mutation and survival

analysis

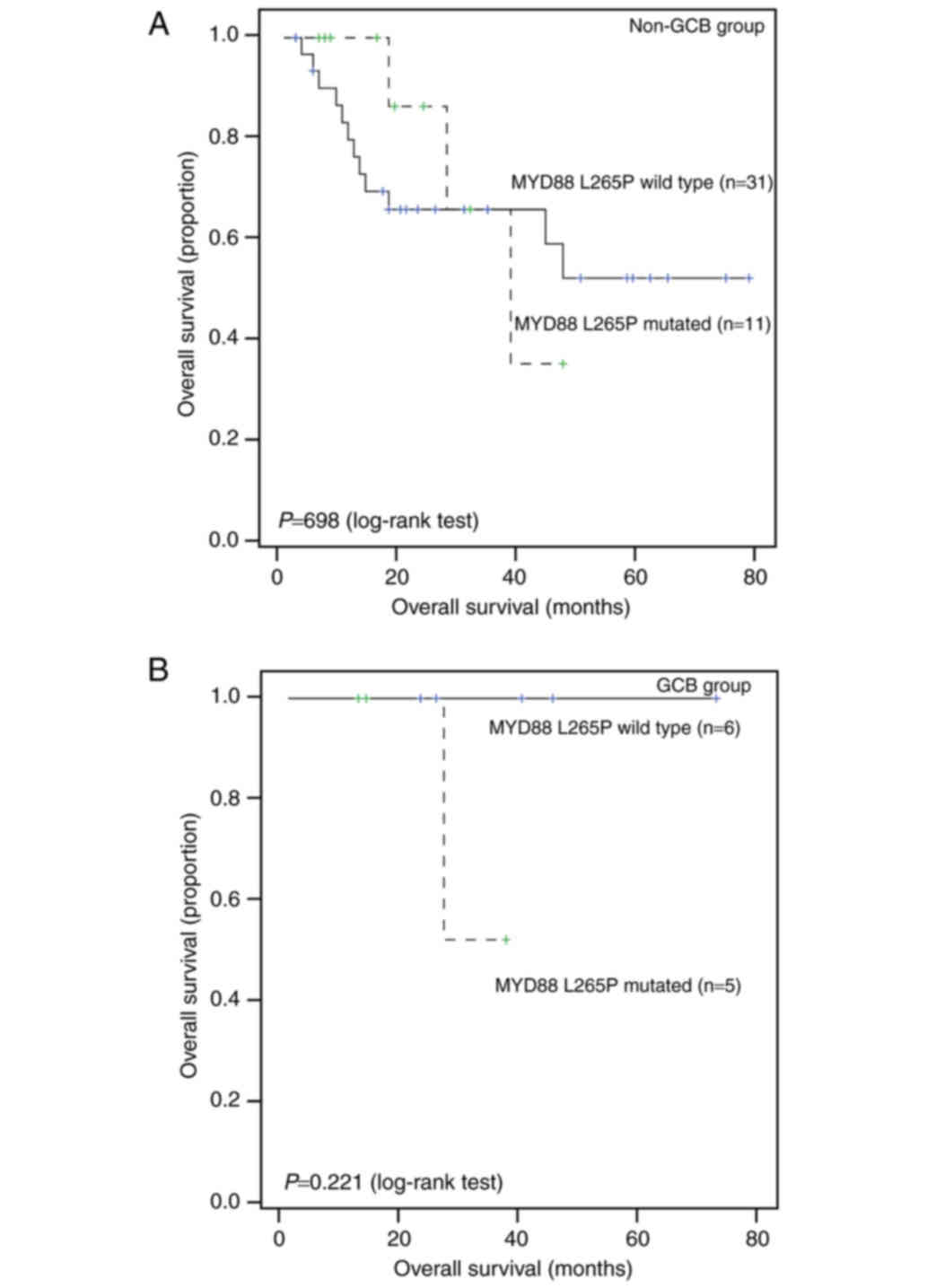

The median follow-up time across the entire cohort

was 18 months (range, 3–80 months), with 3-year OS and PFS rates of

56 and 42%, respectively. Univariate analysis showed that B

symptoms (P=0.004) and Ki-67 (P=0.03) were significantly associated

with PFS. However, the MYD88 mutation status and other

factors showed no association with OS or PFS (Fig. 3). Cox regression showed that B

symptoms remained a significant risk factor for PFS (P=0.012,

hazard ratio (HR) = 3.08; 95% CI = 1.28–7.41) (Table V) after controlling for other factors.

Further subgroup analysis showed that MYD88 mutation status

is not significantly associated with survival in either the Non-GCB

group or the GCB group (all P>0.05; Fig. 4).

| Table V.Clinical characters affecting

progression-free and overall survival. |

Table V.

Clinical characters affecting

progression-free and overall survival.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

|

| OS | PFS | PFS |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Clinicopathologic

parameters | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| MYD88 (WT vs.

L265P) | 0.97

(0.31–3.04) | 0.952 | 0.99

(0.41–2.39) | 0.981 |

|

|

| Age (<60 vs. ≥60

years) | 1.16

(0.43–3.12) | 0.766 | 0.83

(0.37–1.86) | 0.645 |

|

|

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 1.31

(0.48–3.56) | 0.596 | 0.93

(0.42–2.04) | 0.848 |

|

|

| Location (nodal vs.

extranodal) | 0.66

(0.25–1.76) | 0.401 | 1.39

(0.61–3.15) | 0.423 |

|

|

| B symptom (absent

vs. present) | 2.04

(0.69–5.97) | 0.184 | 3.29

(1.39–7.80) | 0.004 | 3.08

(1.28–7.41) | 0.012 |

| Clinical stage

(I–II vs. III–IV) | 2.50

(0.80–7.77) | 0.102 | 1.45

(0.64–3.30) | 0.370 |

|

|

| Subgroup (GCB vs.

non-GCB) | 3.47

(0.46–26.40) | 0.200 | 2.12

(0.63–7.08) | 0.207 |

|

|

| IPI score (0–2 vs.

3–5) | 1.67

(0.62–4.46) | 0.304 | 1.14

(0.51–2.55) | 0.754 |

|

|

| ECOG score (0–1 vs.

2–4) | 2.18

(0.70–6.80) | 0.166 | 2.02

(0.30–5.05) | 0.122 |

|

|

| LDH (normal vs.

high) | 1.50

(0.54–4.15) | 0.429 | 0.93

(0.42–2.04) | 0.845 |

|

|

| Ki-67 (<50 vs.

≥50) | 2.02

(0.27–15.42) | 0.487 | 0.32

(0.11–0.96) | 0.030 | 0.38

(0.12–1.15) | 0.085 |

Discussion

In our study, we developed the ASSN-PCR to detect

the MYD88 L265P mutation and successfully revealed a high

prevalence of the MYD88 L265P mutation in DLBCL patients

undergoing R-CHOP treatment. However, we did not have enough

evidence to conclude that there was a significant association

between the MYD88 L265P mutation and treatment response or

tumor recurrence. The MYD88 L265P mutation may not be a

significant prognostic factor for DLBCL patients undergoing R-CHOP

treatment.

Previous studies have shown that MYD88 L265P

was a key player in the constitutive activation of NF-κB pathways

in lymphomagenesis. It was frequently detected in non-GCB type

DLBCL (21.6–32.5%), as well as extranodal DLBCL, such as in the

central nervous system and testes (50 and 90%, respectively)

(22–24). In our study, MYD88 L265P was

identified in 30.19% of all DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP. The

MYD88 L265P mutation was predominantly detected in non-GCB

type DLBCL (68.8 vs. 31.2% GCB type), as was previously reported

(22,25). It was reported that excessive

activation of NF-κB pathways frequently existed in non-GCB type

DLBCL, which may explain the predominant existence of MYD88

L265P in this subtype (21,26).

In our study, 5 out of 7 primary extranodal DLBCL

patients harboring MYD88 L265P were in the advanced stage.

This result is consistent with a previous study (27) that suggests that the MYD88

L265P gene mutation may be an early molecular change in DLBCL

tumorigenesis (28). Moreover, we

observed a significant association between the MYD88 L265P

mutation and age as well as location, which is consistent with the

previous study (15). With increasing

age, the incidence of poor prognosis factors, such as various

genetic features, non-GCB subtype, and BCL2 expression will

increase for DLBCL (29). This may

explain the predominance of MYD88 L265P in elderly DLBCL

patients. Meanwhile, we discovered that the MYD88 L265P

mutation was not significantly associated with treatment response

or tumor recurrence.

To evaluate the prognostic value of MYD88

L265P for DLBCL, we conducted univariate analyses and multivariate

Cox regression analyses. The presence of B symptoms and

Ki-67>50% indicated poor prognosis. After controlling for other

factors and conducting the cox regression analysis, Ki-67 lost its

prognostic significance. Our results suggest that MYD88

L265P does not affect the outcome of R-CHOP-treated DLBCL patients.

Recent meta-analysis study revealed that the MYD88 L265P mutation

was associated with a low survival rate, except for individual

studies (30). However, since the

study didn't enrolled all published data into pooled analysis, and

pathological type and clinical treatment is various, additional

studies are required with increased number of patients and

differential patient stratification to determine the role of this

mutation.

Limitations of our study include that patients had a

relatively short period of follow-up and the sample size was

relatively small. Therefore, further large-scale, multi-center,

prospective studies with longer follow-up periods are warranted.

Although there are some limitations, the treatment of enrolled

patients was homogeneous; moreover, it is worth noting that we are

the first group to use semi-nested PCR to detect the MYD88

L265P mutation and that the prevalence of detected MYD88

L265P mutations in our study was 30.19%, which is higher than the

prevalence seen when using previously reported methods (13,31).

Excluding the CNS and testicular DLBCLs, the MYD88 L265P

mutation ratio is 27.08%, which is higher than the pooled published

data (16.5%) (30).

As far as we know, some investigators used general

PCR and sequencing to detect MYD88 L265p mutations (10,11,27). MYD88

L265P mutation rate is low and heterogeneous (6.5–19.3%). Since

Sanger sequencing might be unable to detect lower frequency

mutations in FFPE samples with fragmented nucleic acids, AS-PCR was

applied to detect the MYD88 L265P mutation, which is a highly

sensitive and cost-effective (24).

Two powerful studies utilized this method and detected relative

high rate of MYD88 L265P mutation (22–22.3%) (32,33).

Nested PCR is a modification of polymerase chain reaction intended

to reduce non-specific binding in products due to the amplification

of unexpected primer binding sites. In this study, we combined

AS-PCR and semi-nested PCR to assess the MYD88 L265P status.

This method can overcome the issues involved with DNA extraction

from paraffin wax, such as poor quality and low concentration, thus

improving the sensitivity and specificity of PCR. This method can

detect MYD88 L265P at a lower limit of 10−12,

which is more sensitive than the 0.1% previously published for

allele-specific oligonucleotide PCR alone (34).

In conclusion, this study indicates that the

MYD88 L265P mutation is not associated with treatment

response or tumor recurrence and that MYD88 L265P does not

affect patient outcomes and may not be a prognostic factor for

DLBCL patients undergoing R-CHOP treatment. Current data should be

validated in further studies.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Department of Medical

Oncology of Sichuan Cancer Hospital and Institute.

References

|

1

|

Martelli M, Ferreri AJ, Agostinelli C, Di

Rocco A, Pfreundschuh M and Pileri SA: Diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 87:146–171. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Alizadeh AA, Eisen MB, Davis RE, Ma C,

Lossos IS, Rosenwald A, Boldrick JC, Sabet H, Tran T, Yu X, et al:

Distinct types of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identified by gene

expression profiling. Nature. 403:503–511. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Lenz G, Wright G, Dave SS, Xiao W, Powell

J, Zhao H, Xu W, Tan B, Goldschmidt N, Iqbal J, et al: Stromal gene

signatures in large-B-cell lymphomas. N Engl J Med. 359:2313–2323.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht

R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, Van Den Neste E, Salles G,

Gaulard P, et al: CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with

CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma.

N Engl J Med. 346:235–242. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Nowakowski GS and Czuczman MS: ABC, GCB

and double-hit diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Does subtype make a

difference in therapy selection? Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book.

e449–e457. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kawai T and Akira S: The role of

pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on

Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 11:373–384. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Lim KH, Yang Y and Staudt LM: Pathogenetic

importance and therapeutic implications of NF-κB in lymphoid

malignancies. Immunol Rev. 246:359–378. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Davis RE, Brown KD, Siebenlist U and

Staudt LM: Constitutive nuclear factor kappaB activity is required

for survival of activated B cell-like diffuse large B cell lymphoma

cells. J Exp Med. 194:1861–1874. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ngo VN, Young RM, Schmitz R, Jhavar S,

Xiao W, Lim KH, Kohlhammer H, Xu W, Yang Y, Zhao H, et al:

Oncogenically active MYD88 mutations in human lymphoma. Nature.

470:115–119. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kim Y, Ju H, Kim DH, Yoo HY, Kim SJ, Kim

WS and Ko YH: CD79B and MYD88 mutations in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 45:556–564. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Choi JW, Kim Y, Lee JH and Kim YS: MYD88

expression and L265P mutation in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hum

Pathol. 44:1375–1381. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Taniguchi K, Takata K, Chuang SS,

Miyata-Takata T, Sato Y, Satou A, Hashimoto Y, Tamura M, Nagakita

K, Ohnishi N, et al: Frequent MYD88 L265P and CD79B mutations in

primary breast diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Surg Pathol.

40:324–334. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Fernándezrodríguez C, Bellosillo B,

Garcíagarcía M, Sánchez-González B, Gimeno E, Vela MC, Serrano S,

Besses C and Salar A: MYD88 (L265P) mutation is an independent

prognostic factor for outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Leukemia. 28:2104–2106. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Pham-Ledard A, Beylot-Barry M, Barbe C,

Leduc M, Petrella T, Vergier B, Martinez F, Cappellen D, Merlio JP

and Grange F: High frequency and clinical prognostic value of MYD88

L265P mutation in primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma,

leg-type. JAMA Dermatol. 150:1173–1179. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Rovira J, Karube K, Valera A, Colomer D,

Enjuanes A, Colomo L, Martínez-Trillos A, Giné E, Dlouhy I, Magnano

L, et al: MYD88 L265P mutations, but no other variants, identify a

subpopulation of DLBCL patients of activated B-cell origin,

extranodal involvement and poor outcome. Clin Cancer Res.

22:2755–2764. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hattori K, Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Okoshi Y,

Goshima Y, Yanagimoto S, Nakamoto-Matsubara R, Sato T, Noguchi M,

Takano S, Ishikawa E, et al: MYD88 (L265P) mutation is associated

with an unfavourable outcome of primary central nervous system

lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 177:492–494. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Steinhardt JJ and Gartenhaus RB: Promising

personalized therapeutic options for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

subtypes with oncogene addictions. Clin Cancer Res. 18:4538–4548.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Czuczman MS, Dave

SS, Wright G, Grant N, Shovlin M, Jaffe ES, Janik JE, Staudt LM and

Wilson WH: Differential efficacy of bortezomib plus chemotherapy

within molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood.

113:6069–6076. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Swerdllow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, Jaffe

ES, Pileri SA, Stein H, Thiele J and Vardiman JW: WHO

classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues.

2. 4th. IARC Press; France: pp. 4392008

|

|

20

|

Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC,

Gascoyne RD, Delabie J, Ott G, Müller-Hermelink HK, Campo E,

Braziel RM, Jaffe ES, et al: Confirmation of the molecular

classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by

immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood. 103:275–282.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Xu L, Hunter ZR, Yang G, Zhou Y, Cao Y,

Liu X, Morra E, Trojani A, Greco A, Arcaini L, et al: MYD88 L265P

in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, immunoglobulin M monoclonal

gammopathy, and other B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders using

conventional and quantitative allele-specific polymerase chain

reaction. Blood. 121:2051–2058. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kraan W, Horlings HM, van Keimpema M,

Schilder-Tol EJ, Oud ME, Scheepstra C, Kluin PM, Kersten MJ,

Spaargaren M and Pals ST: High prevalence of oncogenic MYD88 and

CD79B mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas presenting at

immune-privileged sites. Blood Cancer J. 3:e1392013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Rossi D: Role of MYD88 in

lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma diagnosis and pathogenesis. Hematology

Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2014:113–118. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Staiger AM, Ott MM, Parmentier S,

Rosenwald A, Ott G, Horn H and Griese EU: Allele-specific PCR is a

powerful tool for the detection of the MYD88 L265P mutation in

diffuse large B cell lymphoma and decalcified bone marrow samples.

Br J Haematol. 171:145–148. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fernández-Rodriguez C, Bellosillo B,

Garcia-Garcia M, Sánchez-González B, Gimeno E, Vela MC, Serrano S,

Besses C and Salar A: MYD88 (L265P) mutation is an independent

prognostic factor for outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Leukemia. 28:2104–2106. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Eliopoulos AG, Stack M, Dawson CW, Kaye

KM, Hodgkin L, Sihota S, Rowe M and Young LS: Epstein-Barr

virus-encoded LMP1 and CD40 mediate IL-6 production in epithelial

cells via an NF-kappaB pathway involving TNF receptor-associated

factors. Oncogene. 14:2899–2916. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Caner V, Sen Turk N, Baris IC, Cetin GO,

Tepeli E, Hacioglu S, Sari I, Zencir S, Dogu MH, Bagci G and Keskin

A: MYD88 expression and L265P mutation in mature B-cell non-Hodgkin

lymphomas. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 19:372–378. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Landau DA, Carter SL, Stojanov P, et al:

Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic

leukemia. Cell. 152:714–726. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Klapper W, Kreuz M, Kohler CW, Burkhardt

B, Szczepanowski M, Salaverria I, Hummel M, Loeffler M, Pellissery

S, Woessmann W, et al: Patient age at diagnosis is associated with

the molecular characteristics of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Blood. 119:1882–1887. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lee JH, Jeong H, Choi JW, Oh H and Kim YS:

Clinicopathologic significance of MYD88L265P mutation in diffuse

large B-cell lymphoma: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 7:17852017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Kim Y, Ju H, Kim DH, Yoo HY, Kim SJ, Kim

WS and Ko YH: CD79B and MYD88 mutations in diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. Hum Pathol. 45:556–564. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Kraan W, Horlings HM, van Keimpema M,

Schilder-Tol EJ, Oud ME, Scheepstra C, Kluin PM, Kersten MJ,

Spaargaren M and Pals ST: High prevalence of oncogenic MYD88 and

CD79B mutations in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas presenting at

immune-privileged sites. Blood Cancer J. 3:e1392013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Rovira J, Karube K, Valera A, Colomer D,

Enjuanes A, Colomo L, Martínez-Trillos A, Giné E, Dlouhy I, Magnano

L, et al: MYD88 L265P mutations, but no other variants, identify a

subpopulation of DLBCL patients of activated B-cell origin,

extranodal involvement and poor outcome. Clin Cancer Res.

22:2755–2764. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Xu L, Hunter ZR, Yang G, Zhou Y, Cao Y,

Liu X, Morra E, Trojani A, Greco A, Arcaini L, et al: MYD88 L265P

in Waldenström macroglobulinemia, immunoglobulin M monoclonal

gammopathy, and other B-cell lymphoproliferative disorders using

conventional and quantitative allele-specific polymerase chain

reaction. Blood. 121:2051–2058. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|