Introduction

It is hypothesized that neuroendocrine carcinoma

(NEC) arise from cells that are involved in the diffuse endocrine

system (1). The biological activity

and prognosis of NEC are associated with various factors, including

the tumor site, histological type and degree of differentiation. A

number of studies have confirmed that poorly differentiated NEC is

associated with an aggressive clinical course and poor prognosis

(2,3). Numerous patients with NEC develop

hepatic metastasis (4), which must

be distinguished from primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HCC

is one of the most common types of tumor worldwide and one of the

most malignant. Furthermore, patients with chronic hepatitis B

viral infection or alcoholic cirrhosis are at increased risk of

developing HCC (5). In the present

case, the patient was diagnosed with primary HCC within a few

months of being diagnosed with a tonsil NEC. Such NEC of the tonsil

tend to be aggressive and are associated with a poor prognosis.

This report describes one case of tonsil neuroendocrine carcinoma

concurrent with hepatocellular carcinoma. Patient provided written

informed consent.

Case report

A 72-year-old male was admitted to the Gaozhou

People’s Hospital (Gaozhou, China) in March 2013 with a four-month

history of a left neck tumor. Fine-needle aspiration of the left

tonsil mass had been performed at two other hospitals and was

identified to be positive for a small-cell malignancy or NEC. The

patient was referred to The Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Guangzhou

Medical University (Guangzhou, China) for further treatment. The

patient’s medical history included hypertension, which had been

present for six years with intermittent use of oral

antihypertensive agents. In addition, the patient was infected with

the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and had suffered with liver cirrhosis

for 15 years. The patient was a non-smoker, however, occasionally

consumed alcohol. The physical examination was notable for a

solitary, left, level II tonsil mass (size, 3.6×2.0 cm), according

to the following chinese antiadoncus clinical classification

system: I, Tonsil enlargement which does not exceed the pharyngeal

arch palate; II, tonsil enlargement exceeds the pharyngeal arch

palate, but does not exceed the midline of the posterior pharyngeal

wall; and III, tonsil enlargement exceeds the midline of the

posterior pharyngeal wall (6).

There were numerous enlarged nodes on each side of the neck; the

largest node was 2.2×1.1 cm. The laboratory tests were abnormal;

the α-fetoprotein (AFP) level had increased to 9.2×104

ng/ml (normal range, 0–25 ng/ml), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9

(normal range, 0–37 U/ml), cancer antigen 125 (normal range, 0–35

kU/l) and neuron specific enolase (NSE; normal range, 0–12.5 U/ml)

were all increasing. In addition, the level of HBV-DNA was

1.62×107 IU/ml (normal range, 0–50 IU/ml). However,

alanine aminotransferase (normal range, 10–40 IU/l), aspartate

aminotransferase (normal range, 10–40 IU/l) and bilirubin (normal

range, 3.4–17.1 μmol/l) were all observed to be within the normal

ranges.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of the

oropharyngeal airway revealed a 3.6-cm mass of the left palate and

there were numerous enlarged nodes on each side of the neck, with

the largest measuring 2.2×1.1 cm. A computed tomography (CT) scan

of the chest and abdomen demonstrated liver cirrhosis, multiple

liver tumors and portal vein thrombosis, as well as metastasis to

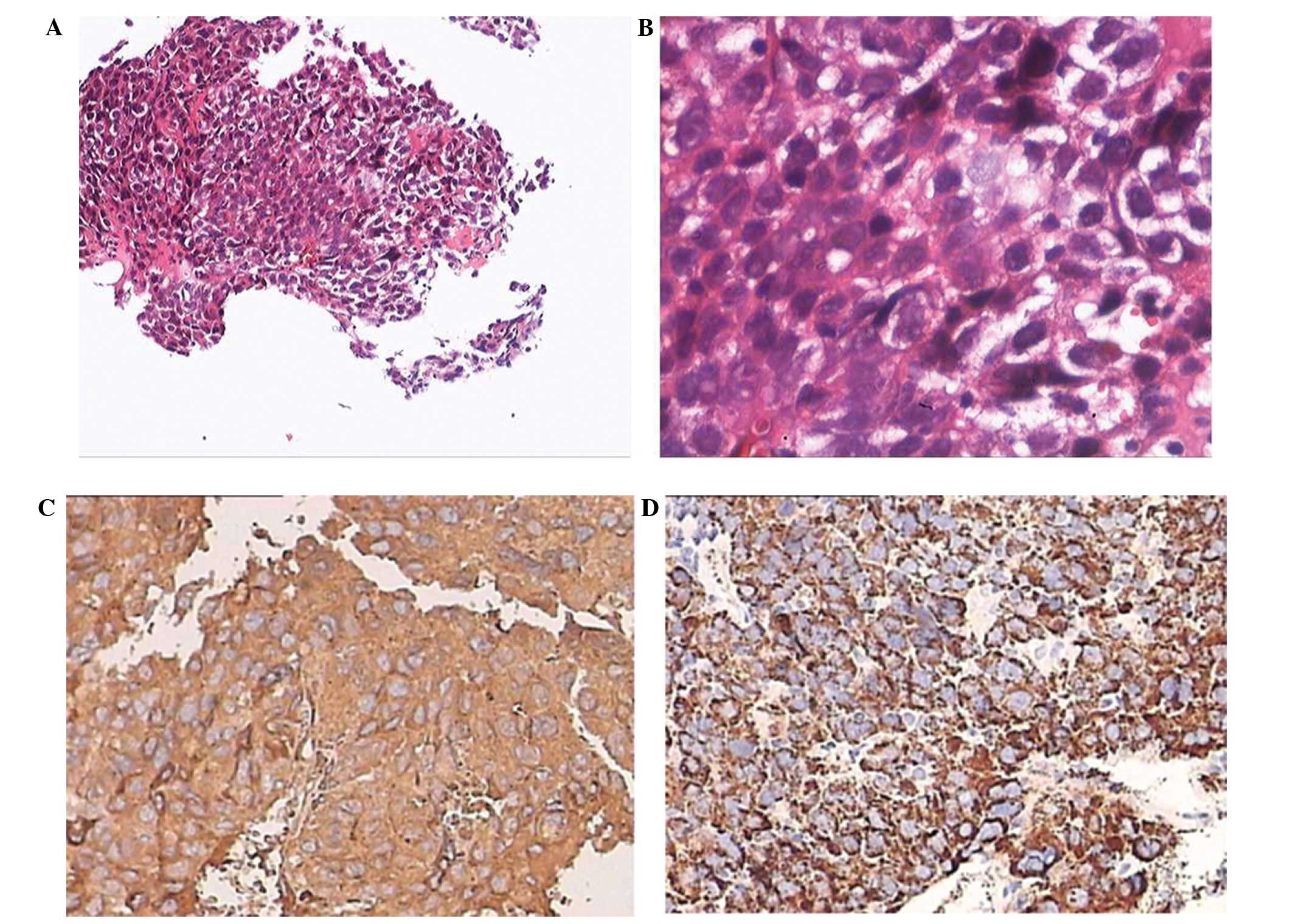

the hilar, abdomen and retroperineum. Histologic examination of the

tonsil revealed an NEC (Fig. 1A and

B). Immunohistochemistry was positive for chromogranin A (CgA),

synaptophysin (Syn), cluster of differentiation (CD)56, AFP, and

some hepatocytes and negative for cytokeratin (CK), p63, melan-A,

CD3, CD10, CD20, CD30, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, CAM5.2,

PAX-5 and CD43. The cell growth index was 80%. Various

tumors located in the right hepatic posterior lobe and right

adrenal gland were identified by color Doppler ultrasound. The

largest liver tumor measured 3.3×3.1 cm and was located in the

right lobe. Histologic examination of the liver revealed a poorly

differentiated primary HCC (Fig. 2A and

B). Immunohistochemistry was positive for Hepatocyte Specific

Antigen antibody (Hep Par-1), AFP, and a small quantity of CK and

was negative for CgA, Syn, CD56 and inhibin. The cell growth index

was 50%. A biopsy of the right adrenal tumor was not performed, as

it was located between the right hepatic lobe and the right kidney

which is unsuitable for biopsy. The size of the oval-shaped tumor

was observed via color Doppler ultrasound to be ~5.3×4.0 cm. The

patient was diagnosed with NEC of the right tonsil with metastatic

disease to the neck, a poorly differentiated HCC, right adrenal

metastatic tumor and level 3 hypertension, and was considered to be

at a particularly high-risk stage. The patient received one cycle

of palliative chemotherapy lasting two days with a cycle duratino

of 21 days with carboplatin (0.5 g) and etoposide (EP; 0.2 g) on

days one to two. The masses continued to grow and the size of the

hepatic tumor increased to 8.0×6.2 cm. Treatment with carboplatin

and EP failed to inhibit the disease progression, and the tonsil

carcinoma became larger and was almost completely blocking the

oropharyngeal airway. Radiotherapy was administered with the aim of

controlling the growth of the tonsil tumor. However, the patient

abandoned the treatment and succumbed due to asphyxia two days

after leaving The Cancer Center of Guangzhou Medical University

(Guangzhou, China).

Discussion

NEC are a heterogeneous family of neoplasms that

possess a broad spectrum of types of histomorphology, tissue

origins and clinical behaviors (7).

NEC generally exhibit slow growth, however, prognosis is dependent

on the tumor site, histological type, degree of differentiation,

mitotic rate, Ki-67 proliferative index, tumor size, depth,

location and the presence of lymph node or liver metastases

(8). The recent WHO classification

(year 2000) defines tumors, on the basis of histopathological and

biological characteristics, into well-differentiated NEC (benign or

uncertain malignancy), well-differentiated NEC (low-grade

malignancy), poorly differentiated NEC (high-grade malignancy) and

mixed tumors (9).

NEC of the head and neck are rare and, therefore,

case reports are only sporadically observed in the literature. A

previous study reported metastatic NEC to the head and neck in

certain primary lung or breast NEC patients (7). In addition, a previous study described

a case of tonsillar metastasis from a primary early-stage large

cell NEC of the lung (10). In the

current patient, the origin of the tumor was hypothesized to be the

tonsil as no tumors were observed in the lung by radiological

examination and there are currently few reports concerning the

metastasis of a tonsil NEC from a primary liver NEC. Furthermore,

the microscopic findings, large size of the tumor and the enlarged

neck lymph nodes supported this hypothesis. Thus, primary NEC

arising from the tonsil was considered to be the most appropriate

diagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, this may be the first

report of a primary tonsil NEC.

The majority of previous reports describe cases of

tumors with a laryngeal origin where the tumors are predominantly

moderately differentiated (11).

However, the pathology slides of the patient in the present study

failed to provide the level of differentiation. In addition, as the

standard therapy for tonsil NEC has not yet been established, the

treatment was conducted with a strategy that is commonly used for

laryngeal NEC. Barker et al (12) investigated 23 adults with

nonsinonasal NEC (NSNEC) of the head and neck, and recommended the

treatment strategy of sequential chemotherapy and radiation. In

this study, there were 19 cases of small-cell undifferentiated

carcinomas and the use of combination chemotherapy approximately

doubled the two-year overall survival and disease-free survival

rates, and reduced the two-year rate of distant metastasis by half.

As NSNEC was found to be highly responsive to cisplatin/EP

combination chemotherapy the induction chemotherapy strategy was

adopted in the present case. However the outcome was not positive

and the efficacy of radiotherapy remains unknown. Further studies

are required to elucidate an optimal treatment strategy for tonsil

NEC.

A total of 50–95% of patients with NEC develop liver

metastases and 80% of patients exhibiting advanced liver disease

succumb within five years of diagnosis (13). Furthermore, certain cases of primary

hepatic NEC have been described in previous studies (14,15).

Therefore, a careful clinical evaluation is essential to

distinguish the extrahepatic origins of tumors; either primary

hepatic NEC or HCC (as in the present case). Kaya et al

(15) reported one case of primary

NEC of the liver in 2001. In this case, the tumor cells were

positively stained for CgA and Syn (the immunological markers for

tumors derived from the neuroendocrine system) and negatively

stained for AFP. In contrast to HCC, hepatic NEC has not previously

been associated with liver cirrhosis. A review of the literature

identified that the immunohistochemical characteristics of HCC

include positivity for the neurosecretory markers, CgA, Syn and

NSE, and negativity for Hep Par-1 (OCH1E5), AFP, thyroid

transcription factor-1, CDX2 and leukocyte common antigen. A

percutaneous biopsy of the liver mass was performed in the present

case and immunohistochemistry revealed a poorly differentiated

HCC.

The incidence of two types of cancer presenting in

one patient is rare; however, ~20% of patients with NEC develop

secondary cancers (8). Combined

primary NEC and HCC of the liver in a 65-year-old male patient was

reported in 2009 by Yang et al (14). It was proposed that the NEC

originated from a poorly differentiated tumor clone of an HCC that

had undergone neuroendocrine differentiation. Ki-67 and p53

expression were identified to be higher in the NEC compared with

that in the HCC. Furthermore, HCC is one of the leading causes of

cancer-associated mortality. HCC progress so rapidly that the

majority of patients are diagnosed with locally advanced or distant

metastasis; therefore, the resulting treatment efficacy and

prognosis is poor. The tumor exhibited a more aggressive clinical

course in accordance with being an NEC, rather than a conventional

HCC, and the patient succumbed due to multiple recurrent tumors and

metastases within a year after surgery. In the present case, the

Ki-67 proliferative index in the tonsil NEC was identified to be

higher than that in the HCC. Considering the aggressive biological

behavior of the NEC, the tonsil NEC was initially treated using

chemotherapy. However, the patient deteriorated and succumbed

within two months of the diagnosis.

In conclusion, NEC of the head and neck is uncommon

and has rarely been described in the tonsil. With regard to NEC,

the prognosis of this type of tumor appears to be poorer when it is

located in the tonsil compared with in other sites of the head and

neck. In addition, it was identified that tonsil NEC is not

sensitive to a chemotherapy regimen that contained carboplatin and

EP. Thus, the optimal treatment for NEC of the tonsil remains

unclear.

References

|

1

|

Clark OH, Benson AB III, Berlin JD, et al:

NCCN Neuroendocrine Tumors Panel Members: NCCN Practice Guidelines

in Oncology: neuroendocrine tumors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw.

7:712–747. 2009.

|

|

2

|

Hochwald SN, Zee S, Conlon KC, et al:

Prognostic factors in pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: an analysis

of 136 cases with a proposal for low-grade and intermediate-grade

groups. J Clin Oncol. 20:2633–2642. 2002.

|

|

3

|

Pape UF, Jann H, Müller-Nordhorn J, et al:

Prognostic relevance of a novel TNM classification system for upper

gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer. 113:256–265.

2008.

|

|

4

|

Soga J1, Yakuwa Y and Osaka M: Carcinoid

syndrome: a statistical evaluation of 748 reported cases. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 18:133–141. 1999.

|

|

5

|

Bruix J and Sherman M; American

Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of

hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 53:1020–1022.

2011.

|

|

6

|

Chen WB, Pan XL, Kang XX, et al: Head.

Diagnostics. 7th edition. People’s Medical Publishing House;

Beijing: pp. 1012007, (In Chinese).

|

|

7

|

Salama AR, Jham BC, Papadimitriou JC and

Scheper MA: Metastatic neuroendocrine carcinomas to the head and

neck: report of 4 cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg

Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 108:242–247. 2009.

|

|

8

|

Ian DH and John AHW: Classification of

neuroendocrine tumors. Clinical Endocrine Oncology. (Part 5)2nd

edition. Wiley-Blackwell; Malden, MA: pp. 4422008

|

|

9

|

Solcia E, Klöppel G and Sonbin LH: World

Health Organization international histological classification of

tumours: Histological typing of endocrine tumours. Clin Endocrinol.

53:7–15. 2000.

|

|

10

|

Sugiura Y, Kaseda S, Kakizaki T, et al:

Tonsillar metastais from primary lung large cell neuroendocrine

carcinoma in the early stage; report of a case. Kyobu Geka.

62:1101–1104. 2009.(In Japanese).

|

|

11

|

Mills SE: Neuroectodermal neoplasms of the

head and neck with emphasis on neuroendocrine carcinomas. Mod

Pathol. 15:264–278. 2002.

|

|

12

|

Barker JL Jr, Glisson BS, Garden AS, et

al: Management of nonsinonasal neuroendocrine carcinomas of the

head and neck. Cancer. 98:2322–2328. 2003.

|

|

13

|

Renner G: Small cell carcinoma of the head

and neck: a review. Semin Oncol. 34:3–14. 2007.

|

|

14

|

Yang CS, Wen MC, Jan YJ, et al: Combined

primary neuroendocrine carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma of

the liver. J Chin Med Assoc. 72:430–433. 2009.

|

|

15

|

Kaya G, Pasche C, Osterheld MC, et al:

Primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the liver: an autopsy case.

Pathol Int. 51:874–878. 2001.

|