Introduction

Facial nerve schwannomas are rare benign tumors,

which originate along the facial nerve. On imaging, those

presenting as an enhancing cerebellopontine angle mass may be

difficult to distinguish from vestibular schwannoma (also termed

acoustic neuroma) and meningiomas. The geniculate ganglion is

located in the temporal bone and contains cell bodies associated

with facial nerve-specialized taste and general somatic sensory

fibers. In the absence of pathological conditions, the geniculate

ganglion is not usually observed under intravenous gadolinium-based

enhancement.

Common clinical presentations of vestibular

schwannoma include ipsilateral sensorineural hearing loss/deafness,

disturbed sense of balance and altered gait, vertigo, nausea and

vomiting, as well as a sensation of pressure in the ears (1). It is generally hypothesized that as

the tumor increases in size, it compresses the brainstem and other

cranial nerves. The facial nerves are rarely involved and, thus,

facial paralysis is an uncommon symptom. However, Mackle et

al (2) reported that 3.7% of

vestibular schwannoma patients do not present with the typical

audiovestibular symptoms that are associated with vestibular

schwannoma. Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient.

Case report

In December 2012, a 36-year-old male was referred to

Shuang Ho Hospital (Taipei, Taiwan) presenting with the sudden

onset of right facial palsy three days previously. The patient had

experienced right facial palsy two years previously and recovered

completely following treatment at another hospital (Far Eastern

Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan). The patient also experienced

the sudden onset of right-sided tinnitus without noticeable hearing

impairment or dizziness. On physical examination, a House-Brackmann

(HB) grade III facial palsy was observed (3). No spontaneous or provoked nystagmus

were identified during a head shaking maneuver. Furthermore, the

tympanic membranes and nasopharynx were unremarkable.

Pure tone audiometry did not reveal any hearing

impairment and the patient’s speech recognition was 100%

bilaterally. In addition, the auditory brainstem response appeared

to be normal. Vestibular evoked myogenic potentials were

symmetrical on either side. The caloric test revealed 38% right

canal paresis, while facial electroneurography demonstrated 80%

degeneration on the right side. The patient did not experience

facial paresthesia or altered sensations of taste. Brain magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a mass (maximal diameter, 1.2

cm) in the right internal auditory canal (Fig. 1). No enhancement was observed at the

labyrinthine portion of the facial nerve or at the geniculate

ganglion.

Following steroidal therapy with prednisolone (1

mg/kg per day) for two weeks, the facial weakness improved to HB

grade I. Considering the patient’s hearing status and that the

tumor remained intracanalicular without any immediate risk of

compressing other vital structures, conservative treatment

(watchful waiting) with an MRI follow-up was performed.

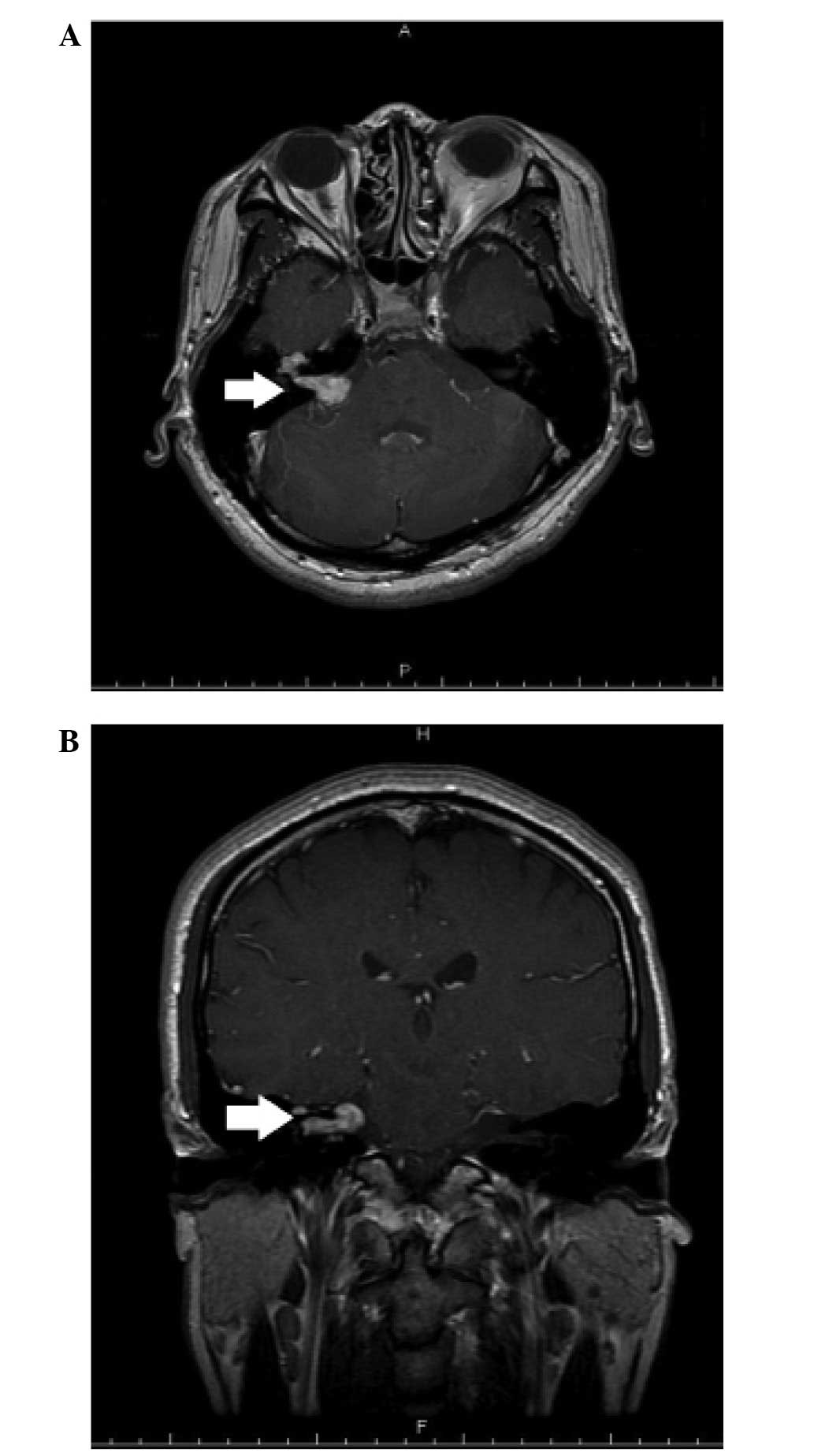

At the one-year follow-up the tumor had enlarged and

extended along the facial nerve to the peri-geniculate area

(Fig. 2). Right-sided tinnitus was

observed, however, the patient’s hearing remained normal. Gamma

Knife radiosurgery using a margin dose of 13 Gy was performed. Six

months following radiosurgery, follow-up MRI imaging revealed that

the tumor was stable without progression. In addition, the

patient’s facial nerve function and hearing remained intact.

Discussion

Facial nerve tumors are rare tumors of the temporal

bone, which may involve any aspect of the facial nerve. However,

facial nerve tumors predominantly present in the peri-geniculate

area and the tympanic segment. Skip lesions or multiple segments of

involvement are occasionally identified. Typical symptoms include

the slow progression of facial nerve paresis or paralysis, as well

as hearing loss, tinnitus, pain and vestibular symptoms.

Furthermore, an ear canal mass may be present (9). Facial twitching followed by

progressive paresis is also a common symptom of this type of tumor.

Facial nerve tumors account for 5% of all cases of facial

paralysis, worldwide and, therefore, must be considered in all

cases of facial palsy (11).

Facial nerve schwannoma are the most common type of

tumor involving the facial nerve. In a series analyzing 600

temporal bones, the incidence of intratemporal facial schwannoma

was 0.8% (12). Perez et al

(13) observed growth in four out

of 13 facial schwannomas that were managed via expectant treatment,

with a mean growth rate of 1.4 mm/year among the tumors that grew

(although if all 13 tumors were considered, the mean growth rate

was 0.42 mm/year). Facial nerve tumors are rarely considered during

the differential diagnoses of enhancing cerebellopontine angle

lesions. In the present case, the diagnosis was based on MRI

enhancement of the geniculate ganglion, a structure that is located

along the facial nerve within the temporal bone.

The management of facial nerve tumors has evolved

from the performance of microsurgical excision with facial nerve

repair (MER) to an increased adoption of more conservative

techniques, which are regarded as facial nerve preservation

approaches (14). These include

observation with the watchful waiting approach, fallopian canal

decompression and stereotactic radiosurgery. All of which are

considered to be important treatment options for the management of

facial nerve tumors (15). There is

controversy regarding the resection of facial nerve tumors of any

size when the facial nerve function is normal or near normal (HB

grade I–II). In cases where tumors are determined to have a high

probability of being facial nerve schwannoma, via imaging or

electrophysiological analysis, preservation of the best possible

facial nerve function must be prioritized regardless of the tumor

size. An exception to this principle includes cases where the tumor

is causing compressive symptoms, such as brainstem compression or

labyrinthine erosion.

Stereotactic radiosurgery is an emerging treatment

modality. Although it has been widely used for treating acoustic

neuroma, there are few reports regarding its use in facial nerve

tumors, however, the number is increasing (2). For facial nerve tumors, the advantages

of stereotactic radiation include the avoidance of surgery,

potential growth arrest of the tumor and possible preservation of

facial nerve function. The selection of treatment is based on the

intent to preserve facial nerve functions at the best possible

level for the longest duration. If patients exhibit a progressively

worsening clinical and radiological condition (HB grade II–IV and

radiological evidence of growth or impending complications)

treatments including, fallopian canal decompression, radiation or

MER are considered to be treatment options that are dependent on

the patient’s situation. Irradiation is an alternative for patients

with early facial dysfunction (HB grade II–III) and a documented

worsening of the clinical and radiological condition. It has a

relatively small, although notable risk of worsening the auditory

and facial function, which must be considered and discussed with

the patient prior to determining the treatment plans (10).

The changes in facial function and tumor sizes of

patients with facial nerve tumors, following stereotactic

radiosurgery from all published studies identified during the

literature search are presented in Table I. Approximately 4% of patients

experienced a decline in facial nerve function and 7% exhibited

tumor enlargement. The current treatment modality relies on

observations with serial MRI for cases with no or limited facial

nerve dysfunction.

| Table ISummary of variations in patient HB

grade and tumor size following stereotactic radiation treatment for

facial nerve tumors, obtained from the literature. |

Table I

Summary of variations in patient HB

grade and tumor size following stereotactic radiation treatment for

facial nerve tumors, obtained from the literature.

| Study [year,

(ref)] | Patients, n | Variation |

|---|

|

|---|

| HB grade | Tumor size |

|---|

| Litre et al

[2007, (4)] | 11 | 3 improved | 4 decreased |

| 8 unchanged | 6 stable |

| | 1 increased |

| Kida et al

[2007, (5)] | 14 | 5 improved | 8 decreased |

| 8 unchanged | 6 stable |

| 1 worsened | |

| Nishioka et al

[2009, (6)] | 4 | 4 unchanged | 2 decreased |

| | 2 stable |

| Madhok et al

[2009, (7)] | 6 | 1 improved | 3 decreased |

| 5 unchanged | 3 stable |

| Hillman et al

[2008, (8)] | 2 | 1 improved | 2 stable |

| 1 unchanged | |

| Wilkinson et

al [2011, (9)] | 6 | 1 improved | 3 decrease |

| 5 unchanged | 1 stable |

| | 2 increased |

| Channer et al

[2012, (10)] | 3 | 1 improved | 3 stable |

| 1 unchanged, 1

worsened | |

The deterioration of facial nerve function or

hearing, rapid tumor growth, or impending labyrinthine erosion or

other complications require the consideration of conducting more

aggressive treatment strategies. Irradiation or fallopian canal

decompression of tumors is often employed for facial nerve function

with an HB grade between II and IV. Microsurgical excision and

facial nerve repair is generally delayed until the facial nerve

function deteriorates to HB grades IV–VI. This is due to the

consideration that postoperative facial nerve paralysis is expected

to last for six to 18 months, which may be followed by an

improvement to an HB grade III at best. In conclusion, the present

case identified that enhancement of the geniculate ganglion is an

important characteristic to identify when evaluating the MRI

appearance of cerebellopontine angle masses. In addition, a more

conservative treatment modality may allow a greater number of

patients to experience improved long-term facial nerve function in

the management of facial nerve tumors.

References

|

1

|

Kirazli T, Oner K, Bilgen C, Ovul I and

Midilli R: Facial nerve neuroma: clinical, diagnostic, and surgical

features. Skull Base. 14:115–120. 2004.

|

|

2

|

Mackle T, Rawluk D and Walsh RM: Atypical

clinical presentations of vestibular schwannomas. Otol Neurotol.

28:526–528. 2007.

|

|

3

|

House JW and Brackmann DE: Facial nerve

grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 93:146–147. 1985.

|

|

4

|

Litre CF, Gourg GP, Tamura M, et al: Gamma

knife surgery for facial nerve schwannomas. Neurosurgery.

60:853–859. 2007.

|

|

5

|

Kida Y, Yoshimoto M and Hasegawa T:

Radiosurgery for facial schwannoma. J Neurosurg. 106:24–29.

2007.

|

|

6

|

Nishioka K, Abo D, Aoyama H, et al:

Stereotactic radiotherapy for intracranial nonacoustic schwannomas

including facial nerve schwannoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys.

75:1415–1419. 2009.

|

|

7

|

Madhok R, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC and

Lunsford LD: Gamma knife radiosurgery for facial schwannomas.

Neurosurgery. 64:2009.

|

|

8

|

Hillman TA, Chen DA and Fuhrer R: An

alternative treatment for facial nerve tumors: short-term results

of radiotherapy. Ear Nose Throat J. 87:574–577. 2008.

|

|

9

|

Wilkinson EP, Hoa M, Slattery WH III, et

al: Evolution in the management of facial nerve schwannoma.

Laryngoscope. 121:2065–2074. 2011.

|

|

10

|

Channer GA, Herman B, Telischi FF, Zeitler

D and Angeli SI: Management outcomes of facial nerve tumors:

comparative outcomes with observation, CyberKnife, and surgical

management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 147:525–530. 2012.

|

|

11

|

O’Donoghue GM, Brackmann DE, House JW and

Jackler RK: Neuromas of the facial nerve. Am J Otol. 10:49–54.

1989.

|

|

12

|

Saito H and Baxter A: Undiagnosed

intratemporal facial nerve neurilemomas. Arch Otolaryngol.

95:415–419. 1972.

|

|

13

|

Perez R, Chen JM and Nedzelski JM:

Intratemporal facial nerve schwannoma: a management dilemma. Otol

Neurotol. 26:121–126. 2005.

|

|

14

|

Minovi A, Vosschulte R, Hofmann E, Draf W

and Bockmuhl U: Facial nerve neuroma: surgical concept and

functional results. Skull Base. 14:195–200; discussion 200–191,

2004.

|

|

15

|

Shirazi MA, Leonetti JP, Marzo SJ and

Anderson DE: Surgical management of facial neuromas: lessons

learned. Otol Neurotol. 28:958–963. 2007.

|