Introduction

Cervical cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed

cancer and the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortalities

in females worldwide. Cervical cancer accounted for 9% (529,800) of

all newly diagnosed cancer cases and 8% (275,100) of all

cancer-related mortalities among females, worldwide in 2008

(1) and >85% of these cases and

mortalities occurred in developing countries (1). According to the American Cancer

Society, the five-year relative survival rate for uterine cervical

cancer diagnosed between 2002 and 2008 in the USA was 69% (2). At present, standard treatment for

cervical carcinoma treatment involves surgery, chemotherapy and

radiotherapy. Combined chemotherapy using cisplatin (DDP) has been

widely approved for the clinical treatment of cervical carcinoma.

Furthermore, a marked decrease in mortality of patients has been

observed with DDP-containing chemotherapy schemes in cervical

carcinoma treatment (3,4). The efficacy of DPP appears to be a

result of its ability to enter cells via multiple pathways and

produce multiple DNA-platinum adducts, which initiate the apoptotic

pathway, resulting in cell death (5). At present, DDP remains a front-line

clinical therapy and constitutes part of the treatment regimen for

patients with various types of cancer. However, drug resistance has

become a major challenge associated with successful DDP treatment

of cervical carcinoma. In addition, the molecular basis for

resistance remains unclear.

DNA-platinum adducts may initiate a cellular

self-defense system, resulting in significant epigenetic and/or

genetic alternations. Previous studies have demonstrated that the

mechanisms underlying DDP resistance are associated with supporting

cell survival, including cell growth-promoting pathways, apoptosis,

developmental pathways, DNA damage repair and endocytosis (6).

In human papillomavirus (HPV) infected cervical

carcinoma, the HPV virus produces E6 and E7 proteins (7) that inactivate cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitors (CKI), including P16INK4A and retinoblastoma

protein (Rb), or cause the overexpression of cyclin D that releases

active E2F, which induces cell cycle traversal (8). It has been reported that irreversible

proliferation arrest is a drug-responsive program, able to

influence the outcome of cancer chemotherapy (9). Certain CKIs, including P21, P27 and

p53, regulate DDP resistance (8) by

mediating the apoptotic pathway (10,11).

However, the association between the cell cycle and DDP resistance

in HPV-infected cervical carcinoma requires further study. The

tumor suppressor and CKI, P16INK4A, which is usually

overexpressed in cervical carcinoma, is not detectable in cervical

carcinomas, which are predominantly sensitive to DDP (12,13),

and the cyclin D-CDK4,6/p16/phosphorylated RB (pRb)/E2F cascade is

altered in >80% of human tumors (14–17).

However, the association between P16INK4A and DDP

resistance in cervical carcinoma remains unclear.

In the present study, the association between p16

and DDP resistance in cevical carcinoma was investigated. The mRNA

and protein expression levels of P16, Cyclin D1 and pRb in SiHa and

SiHa-DDP cell lines were detected, and p16 knock down of a SiHa-DDP

cell line was performed to investigate the possible mechanism of

DDP chemoresistance, which may lead to the development of novel

treatment strategies for chemoresistant cervical carcinoma.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection of

shRNA

SiHa and SiHa-DPP cells were purchased from

Professor Wang He (West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan,

China). The SiHa cell lines were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified

Eagle medium (DMEM; HyClone, Logan, UT, USA) supplemented with 10%

fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hangzhou Sijiqing Biological Engineering

Materials Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) and 50 U/ml penicillin and

streptomycin (all from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen,

China). Human normal oral keratinocytes were cultured in Oral

Keratinocyte Medium (ScienCell Research Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA,

USA) containing 5 ml oral keratinocyte growth supplement and 5 ml

penicillin/streptomycin solution. Transfection was performed when

cells had reached ~80% confluency. P16 shRNA (shP16) and the

control shRNA (0.1 mg; mock) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa

Cruz, CA, USA) vectors were transfected with lipofectamine LTX

reagent with PLUS reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad,

CA, USA). Following transfection, the cells were isolated using

culture medium. Western blot analysis was then performed to

determine the efficiency of p16 knockdown.

mRNA expression analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol Reagent

(Invitrogen Life Technologies) and reverse transcription was

performed using the PrimeScript™ First Strand cDNA synthesis kit

(Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was generated from 5 mg of total

RNA, also according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse

transcription (RT) real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(qPCR) was performed to evaluate the expression levels of P16 mRNA

in the SiHa cell lines. Quantitative PCR was performed using Takara

SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) and an ABI

PRISM® 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster

City, CA, USA). The total reaction volume was 10 μl consisting of 5

μl 2× SYBR premix EX Taq™, 0.5 μl (10 μM) PCR forward primer, 0.5

μl (10 μM) PCR reverse primer, 0.5 μl cDNA and 3.5 μl

dH2O. The sequences of the gene specific primers were as

follows: Forward, 5′-CCTTTGGTTATCGCAAGCTG-3′; and reverse,

5′-CCCTGTAGGACCTTCGGTGA-3′ for P16; forward,

5′-CAAGGGTCATTATGGGTTAGGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-TTAGGTGTAGGGGAGGGGAGA-3′ for pRb; and forward,

5′-AGCCACATCGCTCAGACAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCCCAATACGACCAAATCC-3′

for GAPDH.

Protein expression analysis

Proteins were extracted using cell lysis buffer

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. The protein concentration was

quantified using the Enhanced BCA Protein Assay kit (Beyotime

Institute of Biotechnology). For western blot analysis, equal

amounts of total protein (20 μg) were boiled and separated by

SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, the protein was blotted onto a

polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA,

USA) and blocked for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were

then incubated with human anti-mouse monoclonal p16 antibody

(Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), human anti-mouse polyclonal

pRb and β-actin antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology Inc.,

Danvers, MA, USA), human anti-rabbit monoclonal CDK4 antibody (Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.) overnight at 4°C. The membranes were

then washed with Tris-buffered saline three times prior to

incubation with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat

anti-rabbit CDK4 and HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse p16, Rb and

β-actin secondary antibodies (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

and visualized using an ECL substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Waltham, MA, USA). The membranes were scanned using a myECL Imager

(Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the relative level of protein

expression was analyzed by ImageJ software (imagej.nih.gov/ij/).

3-(4,5-dimethyl-thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

assay

Cells proliferation was measured by MTT assay

(Funakoshi Co., Tokyo, Japan) (20)

in 96-well microculture plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The

cells were seeded at a density of 1×104 cells/well in

96-well plates in DMEM containing 10% FBS. Three duplicate wells

were set up for each group and the experiment was peformed in

triplicate. After 48 h incubation, 20 μl MTT solution (5 mg/ml) in

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), was added to each well for 4 h. The absorbance of

each well was analyzed using an Infinite F50 microplate reader

(Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) at a wavelength of 570 nm.

Proliferation curves were plotted according to the optical

density.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis detection was carried out using Annexin V

flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA, USA) as previously

described (21). Cells were treated

with 2 mM DDP or left untreated, and adherent cells were then

harvested after 72 h and washed in cold PBS, centrifuged at 200 × g

at 4°C for 5 min and resuspended in Annexin-binding buffer. Annexin

V and propidium iodide (Invitrogen Life Technologies) were added to

the cell resuspension and the stained cells were analyzed by flow

cytometry using the S3 cell sorter (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at

wavelengths of 530 and >575 nm.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined using SPSS,

version 16.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Data

are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean.

Results

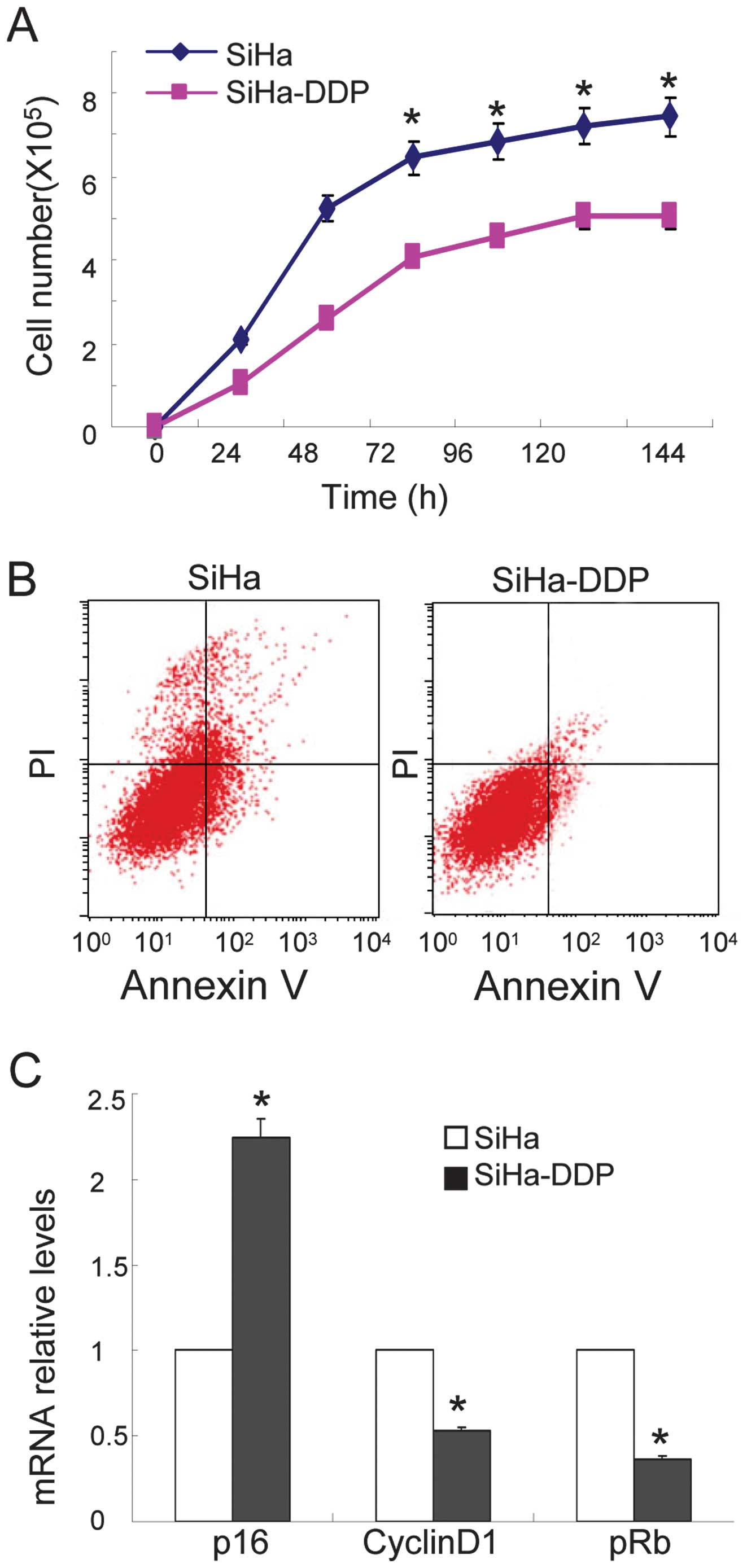

High P16INK4A expression is

associated with reduced cellular growth and apoptosis in SiHa-DPP

cells

The DDP-sensitive and -resistant cervical carcinoma

cell lines were used to compare DDP responses. MTT assay and flow

cytometry were performed to identify the characteristics of human

cervical cancer cells (SiHa) and SiHa-DDP cells. As shown in

Fig. 1A, reduced cellular growth

was observed in the SiHa-DDP cells when compared with SiHa cells,

and less apoptosis was observed in SiHa-DDP cells following

treatment with DDP (Fig. 1B). qPCR

demonstrated that the levels of P16INK4A increased

(Fig. 1C) while cyclin D1 and pRb

levels were downregulated in SiHa-DDP cells when compared with SiHa

cells. These results indicate that SiHa cells resistance to DDP was

associated with high P16INK4A expression levels.

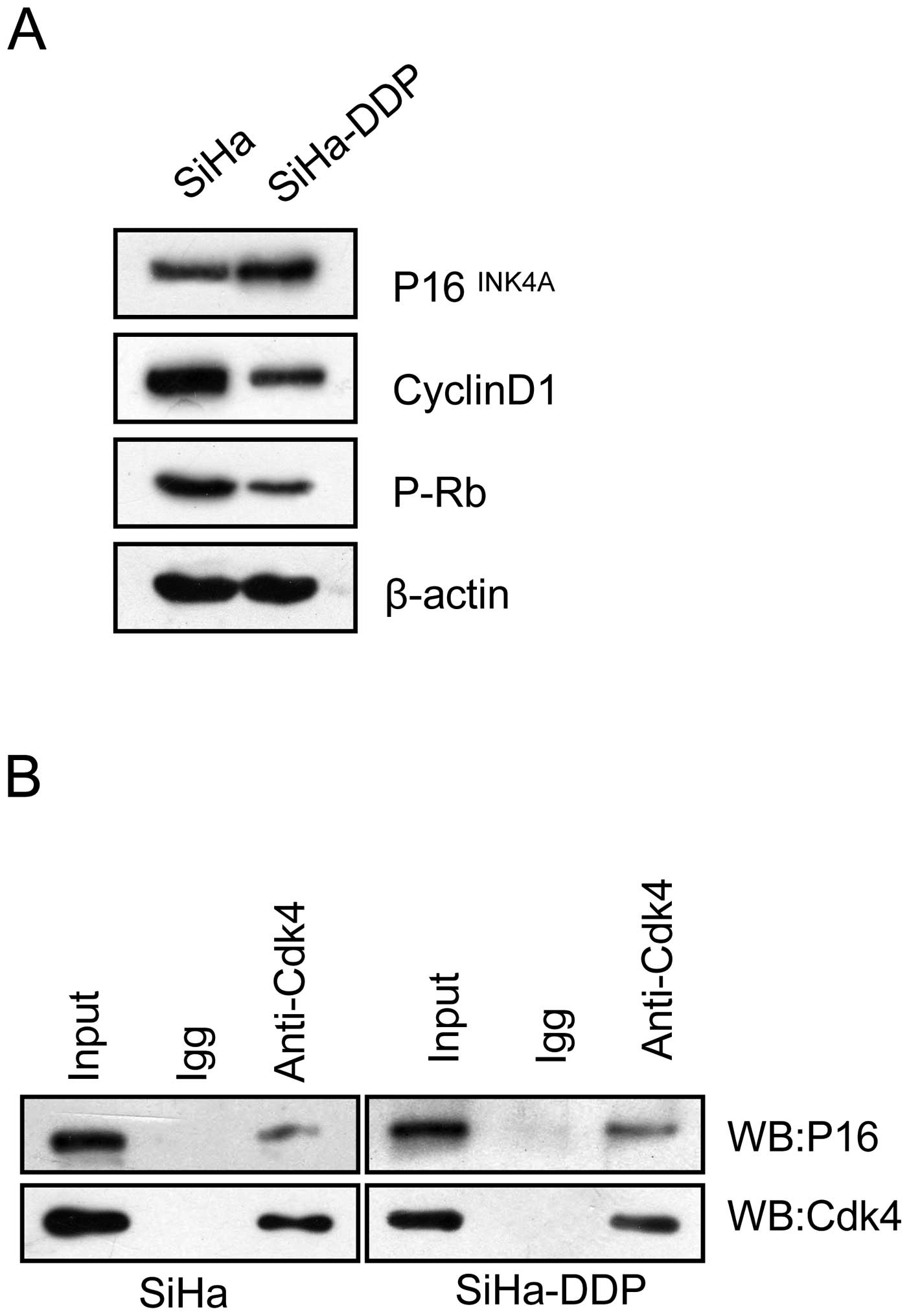

Levels of P16INK4A-CDK4

complex increase in SiHa-DPP cells with pRb inactivation

It has been hypothesized that the cyclin D1-CDK4-pRb

pathway causes DDP resistance via cell cycle arrest (14,15).

Therefore, the influence of P16 on the cyclin D1-CDK4-pRb pathway

in SiHa-DPP cells was analyzed. Co-immunoprecipitation was

performed to evaluate the interaction between P16INK4A

and CDK4 in SiHa-DDP cells and SiHa cells. The results showed that

P16 was coprecipitated with CDK4 in both cell lines (Fig. 2A), and the interaction in SiHa-DDP

was enhanced when compared with SiHa cells, indicating that the

P16-CDK4 complex existed and may be involved in DDP-resistance. To

investigate whether the enhanced levels of the P16-CDK4 complex

contributes to cell cycle arrest, western blot analysis was

performed to detect changes in pRb activity. As shown in Fig. 2B, pRb levels decreased concurrently

with the upregulation of P16INK4A protein levels in

SiHa-DDP cells, indicating that P16 may compete with cyclin D1 to

interact with CDK4, thus inhibiting pRb activation associated with

DDP-resistance in SiHa-DDP cells.

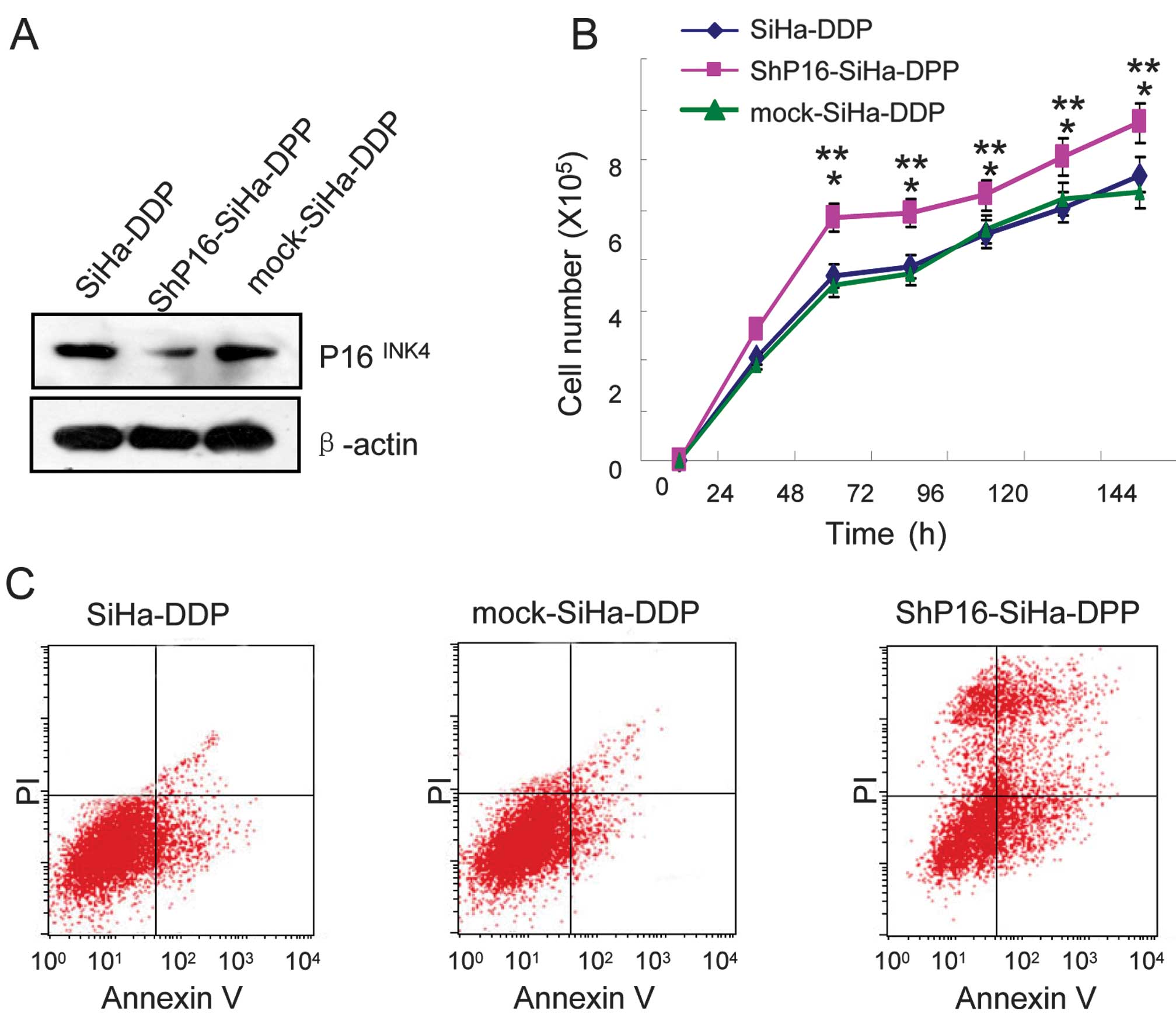

Knockdown of P16INK4A induces

growth and apoptosis in cells treated with DDP

To investigate whether P16INK4A regulates

cellular growth and apoptosis in SiHa-DPP cells and contributes to

DDP-resistance, shRNA and mock of P16INK4A were

transfected into SiHa-DPP cells. Western blot analysis was used to

evaluate the protein levels of P16INK4A. It was

indicated that P16INK4A in shRNA-transfected cells was

markedly downregulated when compared with mock-transfected cells

(Fig. 3A). To investigate the

proliferative effects in shP16-transfected cells, cellular growth

was monitored for 144 h. The shP16-transfected SiHa-DPP cells

exhibited a significant increase in cellular growth when compared

with mock-transfected cells (P=0.05; Fig. 3B). Therefore, the effect of DDP

treatment on the sensitivity of P16INK4A knockdown cells

to DNA damage was assessed. Flow cytometry revealed that

shP16-transfected cells were more sensitive to DDP-induced

apoptosis when compared with mock-transfected cells (Fig. 3C).

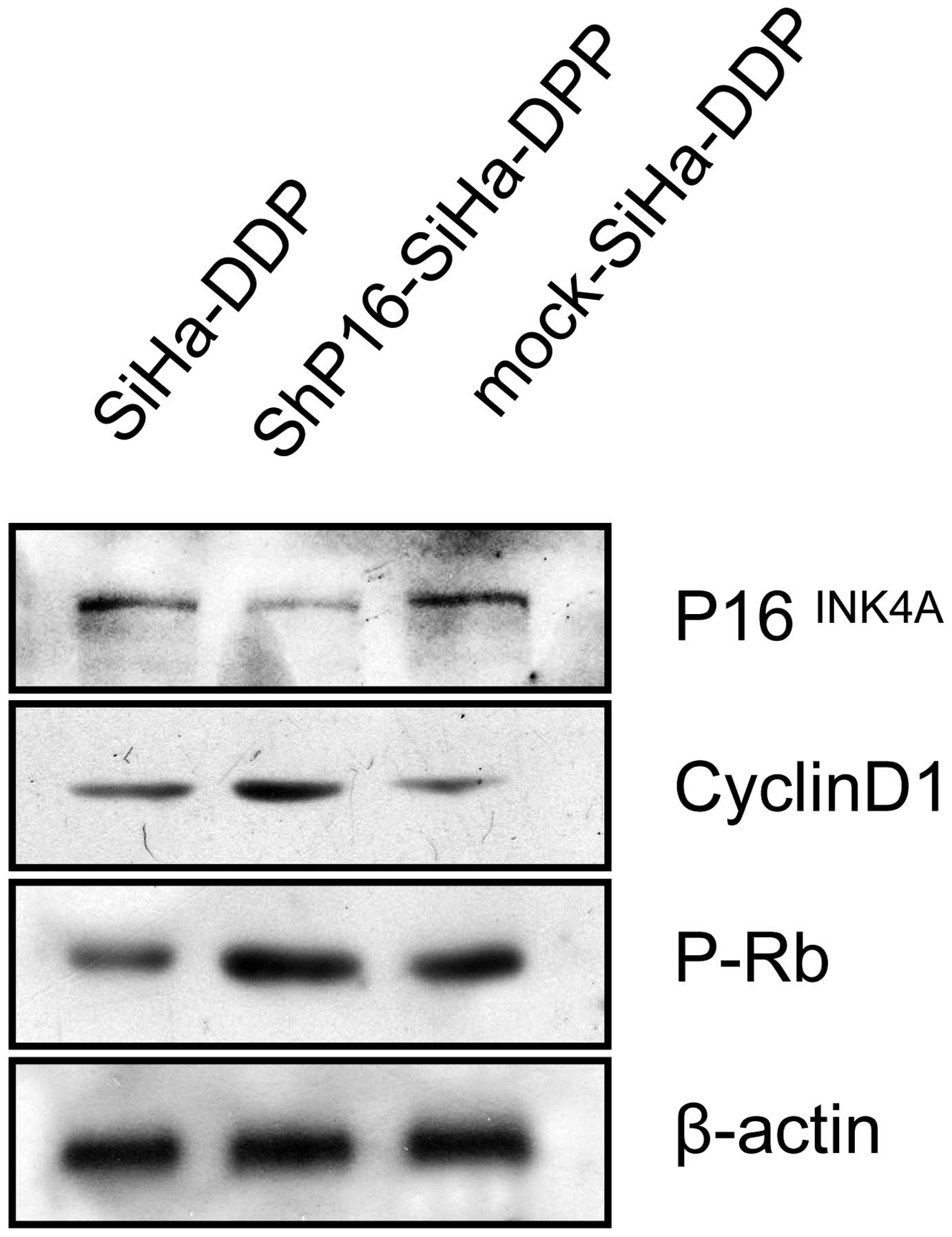

P16INK4A inactivates pRb in

SiHa-DDP cells

To identify the mechanism by which downregulated

P16INK4A influences proliferation, which contributes to

DDP resistance, the protein expression of pRb and cyclin D1 in

SiHa, mock-transfected SiHa-DDP cells and shP16-transfected

SiHa-DDP cells was investigated. pRb and cyclin D1 were

significantly increased in shP16-transfected SiHa-DDP cells

(Fig. 4).

Discussion

Rapidly proliferating cancer cells may be

successfully killed by numerous chemotherapeutic drugs; however,

several healthy proliferating cells are also damaged in the

process, including hair follicle cells, intestinal cells and

hematopoietic precursors. This nonselective killing of rapidly

proliferating healthy cells often causes adverse effects in cancer

patients. Several studies have indicated that CKIs may be used to

protect normal cells from the toxicity caused by chemotherapy

(8).

The cyclin D-CDK4,6/p16/pRb/E2F cascade has been

found to be altered in a number of tumors (18). During the G1 phase of the cell

cycle, Rb is inactivated by sequential phosphorylation events,

which are mediated by various CKIs, including P16INK4A,

which leads to the release of the E2F transcription factors and

promotion of the cell cycle. It appears that the threshold level of

the E2F1 protein, as well as the cell type, determine the function

of the gene (17). DDP-resistant

cells exhibited less and delayed growth when compared with

non-resistant (siHa) cells (13). A

reasonable explanation may be that the depressed growth of siHa-DDP

cells was attributable to an elevated cellular p16 level, which

caused proliferation arrest.

In the present study, SiHa human cervical carcinoma

cells, which are known to be infected with HPV, were used (8). The results showed high

P16INK4A expression and its enhanced interaction with

CDK4 in cervical carcinoma DDP-resistance cells (SiHa-DPP), which

may cause irreversible proliferation arrest. Knockdown of

P16INK4A induced cells exiting the G1 phase into the S

phase and promoted their proliferation, which enhanced DDP

chemosensitivity as DDP targets cells in the S phase. Previous

studies have revealed that the induction of P16INK4A,

p21Waf1 or p27Kip1 lead to significant

resistance to DDP-mediated cytotoxicity in the human cervical

cancer cells, but not in the SiHa cells (19). This indicated that high expression

of p16INK4A in SiHa-DDP cells was required for DDP

resistance, but did not cause it, implying that additional factors

coordinated with P16INK4A, leading to DDP resistance in

HPV-infected cervical carcinoma cells. Therefore, future studies

are required to confirm the identity of such factors.

CKI-mediated resistance to chemotherapy may be a

useful approach to protect normal cells from chemotherapy-induced

toxicity in patients with pRb pathway-impaired cancer. Our results

provided the first evidence that P16INK4A regulated DDP

resistance in cervical carcinoma SiHa cells, which may lead to the

development of novel strategies for the treatment of chemoresistant

cervical carcinoma.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The Third Xiangya Hospital

of Central South University (Changsha, China).

References

|

1

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al: Global

cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel R, Naishadham D and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 63:11–30. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kondagunta GV, Sheinfeld J, Mazumdar M, et

al: Relapse-free and overall survival in patients with pathologic

stage II nonseminomatous germ cell cancer treated with etoposide

and cisplatin adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 22:464–467.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Einhorn LH: Role of the urologist in

metastatic testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 25:1024–1025. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Siddik ZH: Cisplatin: mode of cytotoxic

action and molecular basis of resistance. Oncogene. 22:7265–7279.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Shen DW, Pouliot LM, Hall MD and Gottesman

MM: Cisplatin resistance: a cellular self-defense mechanism

resulting from multiple epigenetic and genetic changes. Pharmacol

Rev. 64:706–721. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

del Moral-Hernández O, López-Urrutia E,

Bonilla-Moreno R, Martínez-Salazar M, Arechaga-Ocampo E, Berumen J

and Villegas-Sepúlveda N: The HPV-16 E7 oncoprotein is expressed

mainly from the unspliced E6/E7 transcript in cervical carcinoma

C33-A cells. Arch Virol. 155:1959–1970. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Schmidt M and Fan Z: Protection against

chemotherapy-induced cytotoxicity by cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitors (CKI) in CKI-responsive cells compared with

CKI-unresponsive cells. Oncogene. 20:6164–6171. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Rebbaa A: Targeting senescence pathways to

reverse drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Lett. 219:1–13. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Koster R, di Pietro A, Timmer-Bosscha H,

Gibcus JH, van den Berg A, Suurmeijer AJ and Bischoff R:

Cytoplasmic p21 expression levels determine cisplatin resistance in

human testicular cancer. J Clin Invest. 120:3594–3605. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Mandic R, Schamberger CJ and Müller JF:

Reduced cisplatin sensitivity of head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma cell lines correlates with mutations affecting the

COOH-terminal nuclear localization signal of p53. Clin Cancer Res.

11:6845–6852. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sari Aslani F, Safaei A, Pourjabali M and

Momtahan M: Evaluation of Ki67, p16 and CK17 markers in

differentiating cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and benign

lesions. Iran J Med Sci. 38:15–21. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Vogelstein B and Kinzler KW: Cancer genes

and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 10:789–799. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nevins JR: The Rb/E2F pathway and cancer.

Hum Mol Genet. 10:699–703. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Kaye FJ: RB and cyclin dependent kinase

pathways: defining a distinctionbetween RB and p16 loss in lung

cancer. Oncogene. 21:6908–6914. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Giacinti C and Giordano A: RB and cell

cycle progression. Oncogene. 25:5220–5227. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Crosby ME and Almasan A: Opposing roles of

E2Fs in cell proliferation and death. Cancer Biol Ther.

3:1208–1211. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Pei XH and Xiong Y: Biochemical and

cellular mechanisms of mammalian CDK inhibitors: a few unresolved

issues. Oncogene. 24:2787–2795. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Chen XL, Wang H, Zhang XM, et al:

Establishment of a cisplatin-resistant human cervical cancer cell

line. Sichuan Da Zue Zue Bao Yixue Ban. 43:151–155. 2012.(In

Chinese).

|

|

20

|

Uchida F, Uzawa K and Kasamatsu A:

Overexpression of CDCA2 in human squamous cell carcinoma:

correlation with prevention of G1 phase arrest and apoptosis. PLoS

One. 8:e563812013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Al-Khalaf HH, Colak D and Al-Saif M: p16

(INK4a) positively regulates cyclin D1 and E2F1 through negative

control of AUF1. PLoS One. 6:e211112013. View Article : Google Scholar

|