Introduction

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is one of the

leading causes of cancer death among women worldwide (1). Although continuous improvement in

surgical techniques and initial response to chemotherapy has been

made in the past few decades, recurrence still occurs in ~70% of

patients who underwent the first-line chemotherapy within 18 months

(2,3). The 5-year survival rate remains poor

at 30.6% for patients with advanced EOC (4,5). Thus,

it is of great clinical importance to develop effective

chemotherapy strategies for EOC.

Differentiation therapy has emerged as a potential

chemotherapy strategy against tumors (6). The clinical effectiveness of

differentiation therapy has been demonstrated in acute

promyelocytic leukemia (APL) using all-trans-retinoic acid

as an inducer (7). Recently,

arsenic trioxide (As2O3), a well-established

human carcinogen, has also proven to be a differentiation agent in

the treatment of APL patients (8).

Of interest, such effects are not reliably reproduced in solid

tumors. Differentiation agents for ovarian cancer remain

elusive.

Thrichostatin A (TSA), a hydroxamate-type histone

deacetylase inhibitor, can promote histone acetylation by

remodeling of chromatin architecture, and induce cell

differentiation (9). TSA also

catalyzes the acetylation of non-histone proteins, which may

regulate signaling related to tumorigenesis (10,11).

Accumulated evidence indicates that TSA can activate AKT signaling

pathway (12). Overexpression of

epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), the upstream effector of

AKT, has been associated with increased chemoresistance and poorer

clinical outcome (13,14). However, it is unclear whether TSA

transactivates the EGFR/AKT pathway in EOC, and whether the

blockage of this pathway can potentiate the effect of TSA on EOC

differentiation.

In this study, we demonstrate that TSA can induce

cellular differentiation in HO8910 ovarian cancer cells. We show

that TSA transiently activates EGFR/AKT signaling pathway, causing

expression of differentiation-related genes, and blocking this

pathway sensitizes HO8910 cells to TSA. This implies that a

combination of EGFR/AKT pathway inhibitors with TSA may represent a

better differentiation therapy strategy for ovarian cancer.

Materials and methods

Cell line and culture

Human ovarian cancer cell line, HO8910, was kindly

provided by Dr Qixiang Shao of Jiangsu University (Zhenjiang,

China). The HO8910 cells were derived from ascites of ovarian

adenocarcinoma patients. The cells were maintained for no longer

than 3 months as described previously (15).

Antibodies and reagents

EGFR, phospho-EGFR (Tyr992), AKT, phospho-AKT

(Ser473), FOXA2, and acetyl-histone H3K9 antibodies were purchased

from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). α-tubulin and

secondary antibodies were procured from Bioworld Technology

(Shanghai, China). OCT4, SOX2, p21Cip1, cyclin D1, and

histone H3 antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA,

USA). The EGFR inhibitor AG1478, AKT inhibitor A6730, and HDAC

inhibitor TSA were procured from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). TSA

and A6730 were dissolved in ethanol as stocks (6.6 mM) and dimethyl

sulfoxide as stocks (20 mM), respectively.

Drug treatment

In TSA experiments, HO8910 cells were incubated with

100, 200, and 400 nM TSA and harvested at 48 h. When the expression

of differentiation-related genes was examined, cells were harvested

at 24 h. For cotreatment of TSA and EGFR pathway inhibitors, cells

were incubated with 200 nM TSA in presence of AG1478 (10 µM) or

A6730 (20 µM) for 24 h.

Morphological evaluation

The morphological changes in TSA-treated cells were

observed during a 72-h time course with a light microscope

(Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), and images were obtained via a CCD camera

(Olympus).

Histone protein and whole-cell

extraction and western blotting

Histones were prepared using the bioepitope nuclear

and cytoplasmic extraction kit (Bioworld Technology) following the

manufacturer's protocol. Total cellular proteins were isolated

directly from cultures in 100-mm Petri dishes after being washed

with ice-cold PBS and the addition of 200 µl Cell and Tissue

Protein Extraction reagent (Kangchen Biotech, Shanghai, China),

containing protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails

(Roche). Antibodies against OCT4 (1:5,000), SOX2 (1:5,000), FOXA2

(1:1,000), cyclin D1 (1:10,000), p21Cip1 (1:3,000), EGFR

(1:1,000), p-EGFR (1:600), AKT (1:1,000), p-AKT (1:800), α-tubulin

(1:1,000), and histone H3 (1:2,000) were used for western blot

analysis, which was performed as described previously (16).

Cell proliferation assays

The cell proliferation assays were performed using

CCK-8 and EdU. Briefly, HO8910 cells (5×103) were seeded

in 96-well plates, and then treated with TSA for 24, 48, and 72 h.

For CCK-8 analysis, the cells were incubated with 1/10 volume of

CCK-8 for 2 h. The plates were then read at 450 nm with a Bio-Rad

model 680 microplate reader (Richmond, CA, USA). The cell

proliferation rate =

ODexperiment/ODcontrol×100%. For EdU assay,

HO8910 cells were treated with 200 nM TSA for 48 h, and then

incubated with EdU (50 mM) for 2 h, after which the nuclei were

stained with DAPI. The images were photographed by an Olympus

inverted microscope system.

Cell cycle analysis

The effect of TSA on HO8910 cell cycle phase

distribution was determined by flow cytometry. HO8910 cells were

fixed in 70% ethanol for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were then

incubated with propidium iodide (50 µg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C,

after which the fluorescence was measured with a flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical

significance was calculated by Student's t-test or ANOVA, and

values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

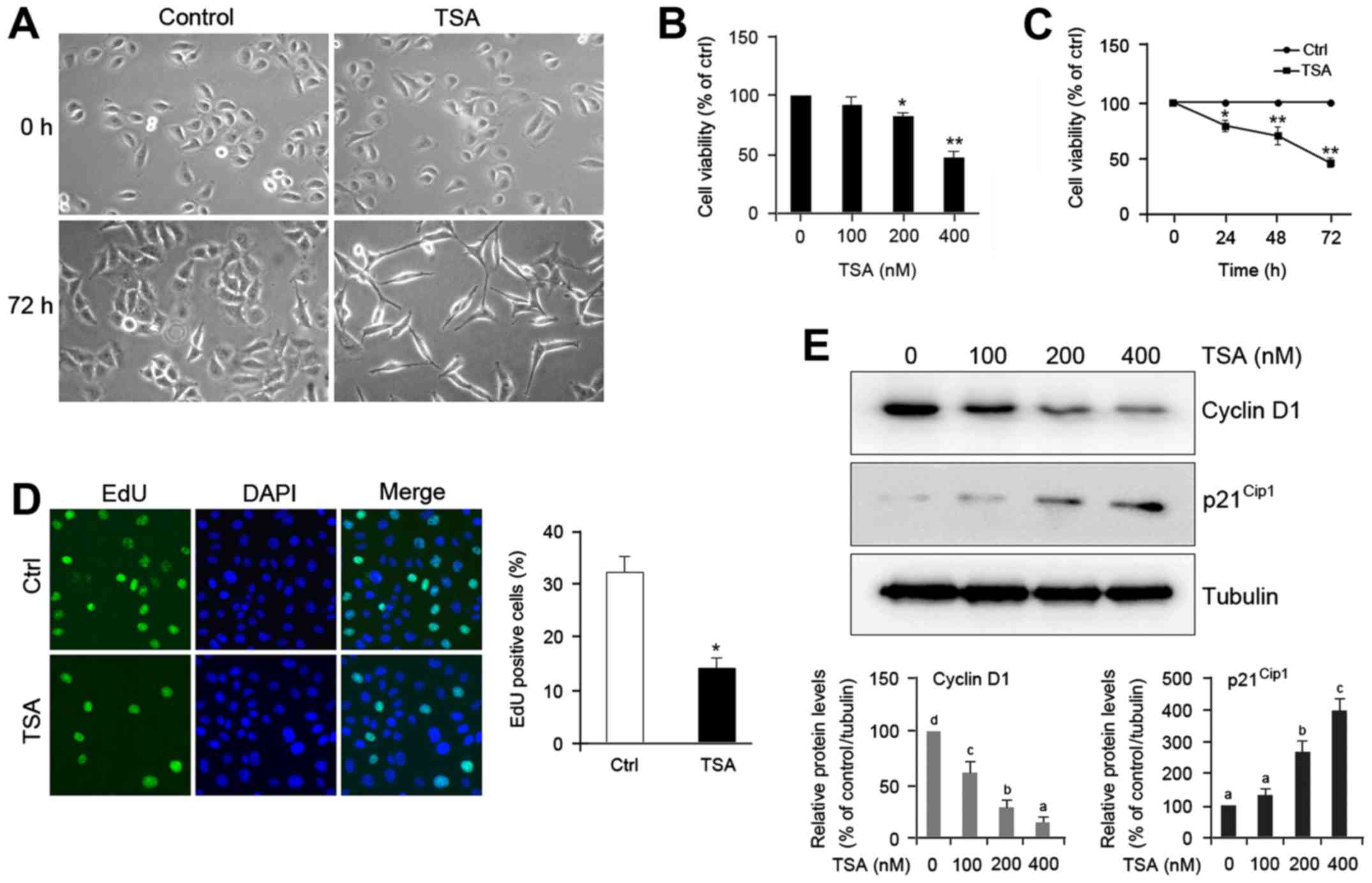

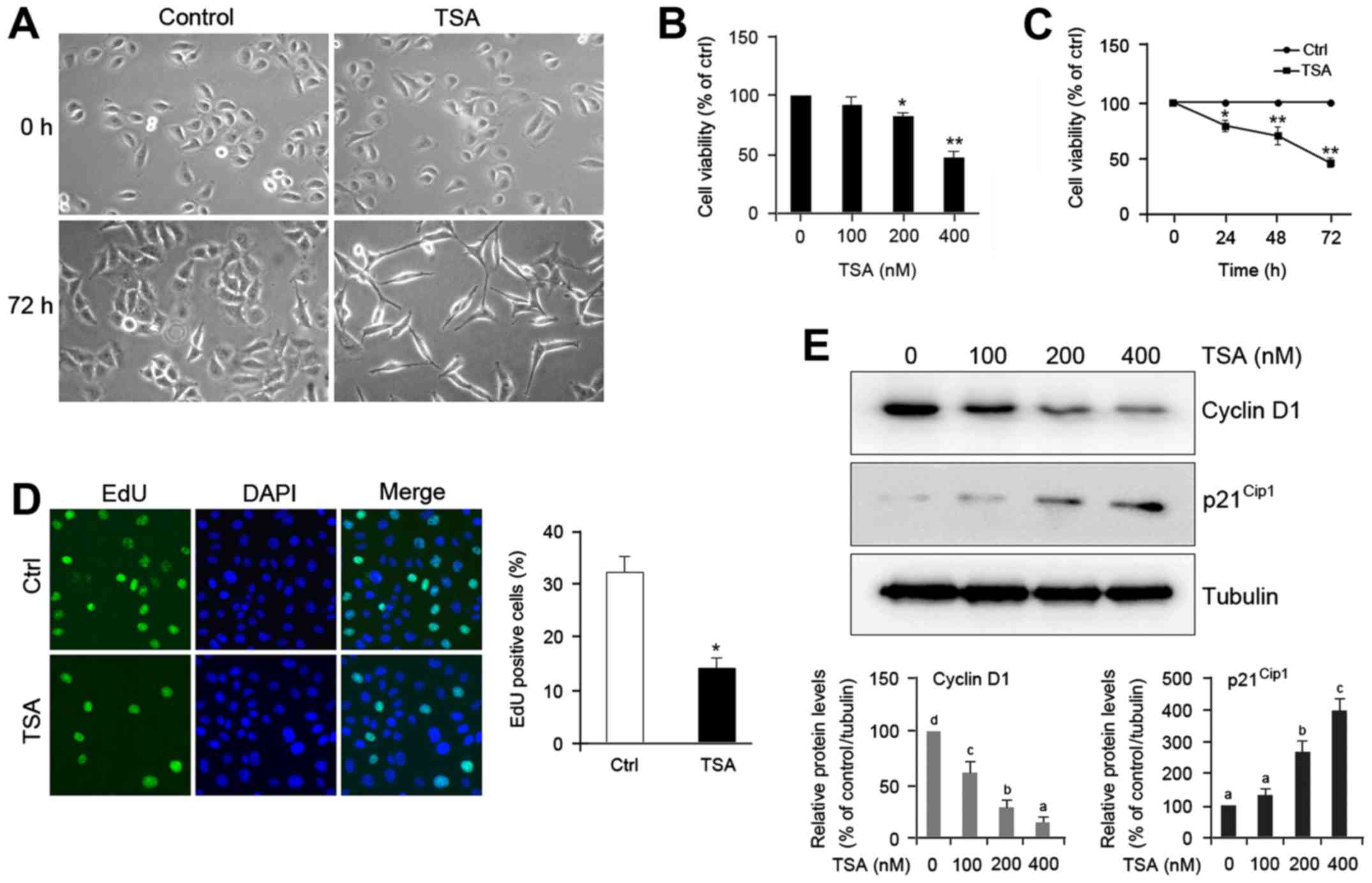

TSA induces morphological changes of

HO8910 cells

To elucidate the effect of TSA on ovarian cancer

cell differentiation, we examined the morphology of HO8910 cells

treated with or without TSA. Microscopic observation of control

cells revealed round, stellate-like appearance and growth in

clusters. Unlike the morphology of control, a majority of

TSA-treated cells exhibited spindle shape and much longer, fine,

tapering processes (Fig. 1A).

Treatment with TSA also caused a decrease in cell density (Fig. 1A), which suggests that TSA may

impede proliferation of HO8910 cells. Consistent with this

prediction, we found that TSA treatment caused a notable reduction

in cell proliferation rate compared with the control in a dose- and

time-dependent manner (Fig. 1B and

C). The suppressive effect of TSA on cell proliferation was

further confirmed by 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) assay

(Fig. 1D).

| Figure 1.TSA induces cell differentiation and

proliferation inhibition of HO8910 ovarian cancer cells. (A) Cells

were incubated without or with 200 nM thrichostatin A (TSA) for the

indicated times (magnification, ×200). (B) Cells were treated with

different doses of TSA for 48 h, and cell proliferation was

analyzed by CCK-8 assay. (C) Cells were treated with 200 nM TSA for

the indicated times, after which cell proliferation was detected

via CCK-8 assay. (D) Cells were treated without or with TSA 200 nM

TSA for 48 h, and then incubated with 50 mM

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) for 2 h and the nuclei were stained

with DAPI. Representative micrographs (left panel, magnification,

×400) and quantification (right panel) of EdU-incorporating cells

in control and TSA-treated cells. Green, EdU; blue, DAPI. The error

bars represent mean ± SEM (n=3). Statistical differences compared

with the controls are given as *P<0.05 and **P<0.01

(Student's t-test). (E) Cells were treated with different doses of

TSA for 48 h. Total protein was extracted and blotted with

antibodies against cyclin D1, p21Cip1, and α-tubulin.

The error bars represent the mean ± SEM (n=3). Values within the

same row with different superscripted letters are significantly

different, P<0.05 (one-way ANOVA). |

To identify the mechanism of action of TSA in

decreasing cell proliferation, we undertook cell cycle analysis

with propidium iodide to label DNA. Table I reveals that treatment with TSA for

48 h led to an accumulation of HO8910 cells in the

G0/G1 phase (60.2 vs. 82.8%, P<0.05) and a

concomitant decrease in the S-phase cell fraction (26.7 vs. 3.8%,

P<0.01). The TSA-induced cell cycle arrest was further confirmed

by examining the expression of cell cycle regulatory protein cyclin

D1 in HO8910 cells. Western blot analysis indicated that TSA

treatment exhibited decrease of cyclin D1 levels and increase of

p21Cip1 protein (Fig.

1E). These data suggest that TSA induces cell differentiation

and proliferation inhibition of HO8910 cells.

| Table I.TSA causes cell cycle arrest in

G0/G1 phase in HO8910 cells. |

Table I.

TSA causes cell cycle arrest in

G0/G1 phase in HO8910 cells.

|

| Control | TSA (nM) |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Groups | 0 | 200 |

|---|

|

G0/G1 | 60.2±1.8 |

82.8±1.7a |

| S | 26.7±1.3 |

3.8±0.6b |

Molecular evidence of TSA-induced

differentiation of HO8910 cells

To verify the role of TSA in HO8910 cell

differentiation, two groups of genes including FOXA2 as

differentiation marker gene, and SOX2 and OCT4 as pluripotency

marker genes were evaluated quantitatively. FOXA2 gene was

evaluated because it plays important roles in regulating the

expression of genes involved in cell differentiation in a number of

different organs (17), and is

essential for differentiation and development of glands in mouse

uterus (18). A dose-dependent

upregulation of FOXA2 protein and H3K9 acetylation was observed in

TSA-treated cells compared with the controls (Fig. 2). In contrast, the expression of

SOX2 and OCT4 proteins was notably restrained by TSA (Fig. 2). This molecular evidence confirms

that TSA actually induces the differentiation of HO8910 cells.

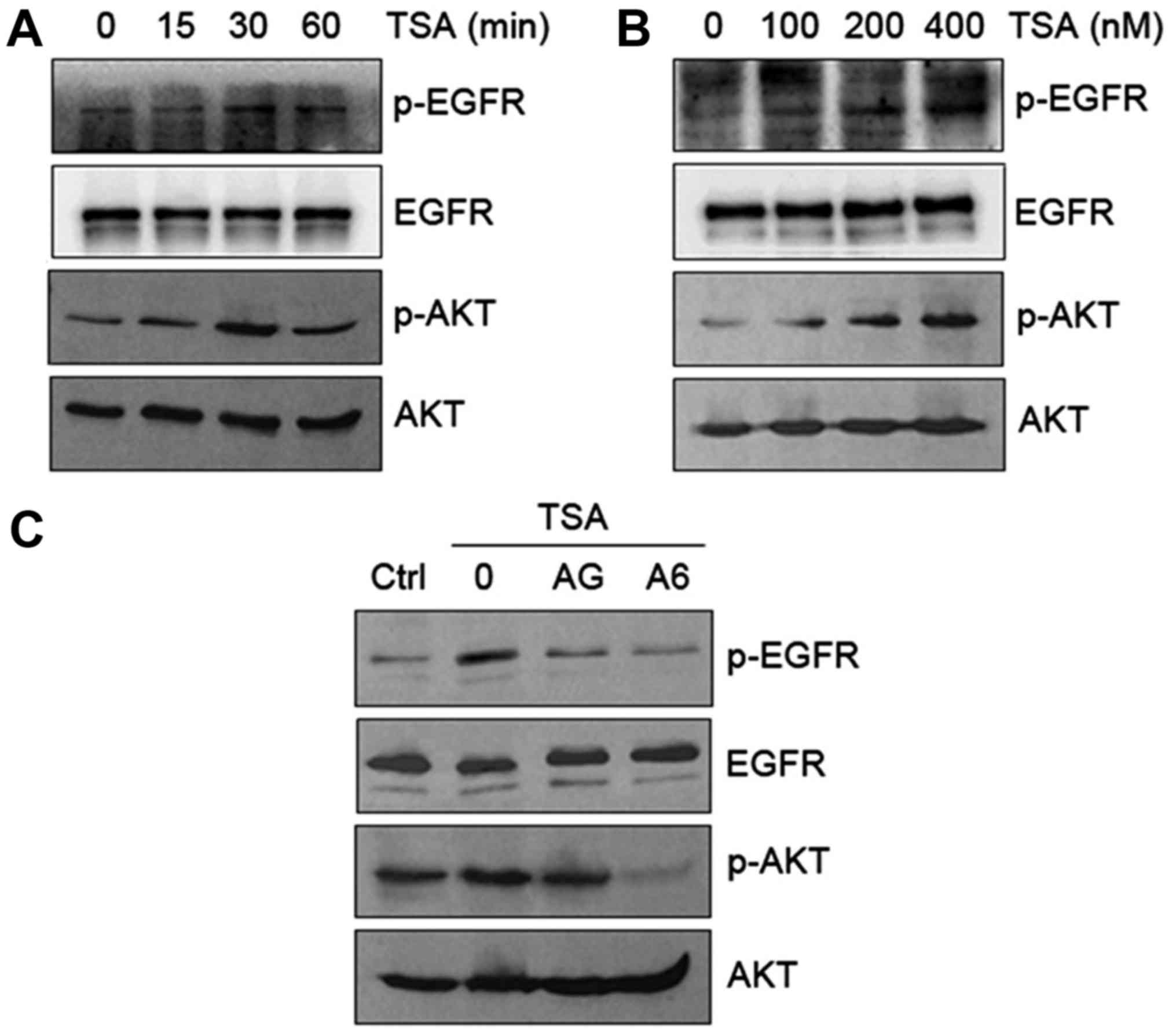

Transactivation of EGFR/AKT pathway by

TSA in HO8910 cells

Since EGFR expression strongly correlates with tumor

resistance to cytotoxic agents (19), EGFR could be a potential target for

anticancer therapy. To decipher whether TSA transactivates EGFR in

HO8910 cells, we first examined phosphorylation of EGFR and AKT in

response to TSA. Our results indicated that TSA caused a time- and

dose-dependent increase in phosphorylation of EGFR (Tyr992) and AKT

(Ser473) (Fig. 3A and B). The

TSA-induced phosphorylation of EGFR and AKT occurred at 15 min and

peaked at 30 min (Fig. 3A). The

observed changes in EGFR and AKT phosphorylation were reversed in

HO8910 cells in response to EGFR inhibitor AG1478 and AKT inhibitor

A6730 (Fig. 3C). These data suggest

that TSA activates EGFR phosphorylation and subsequent activation

of downstream AKT signaling.

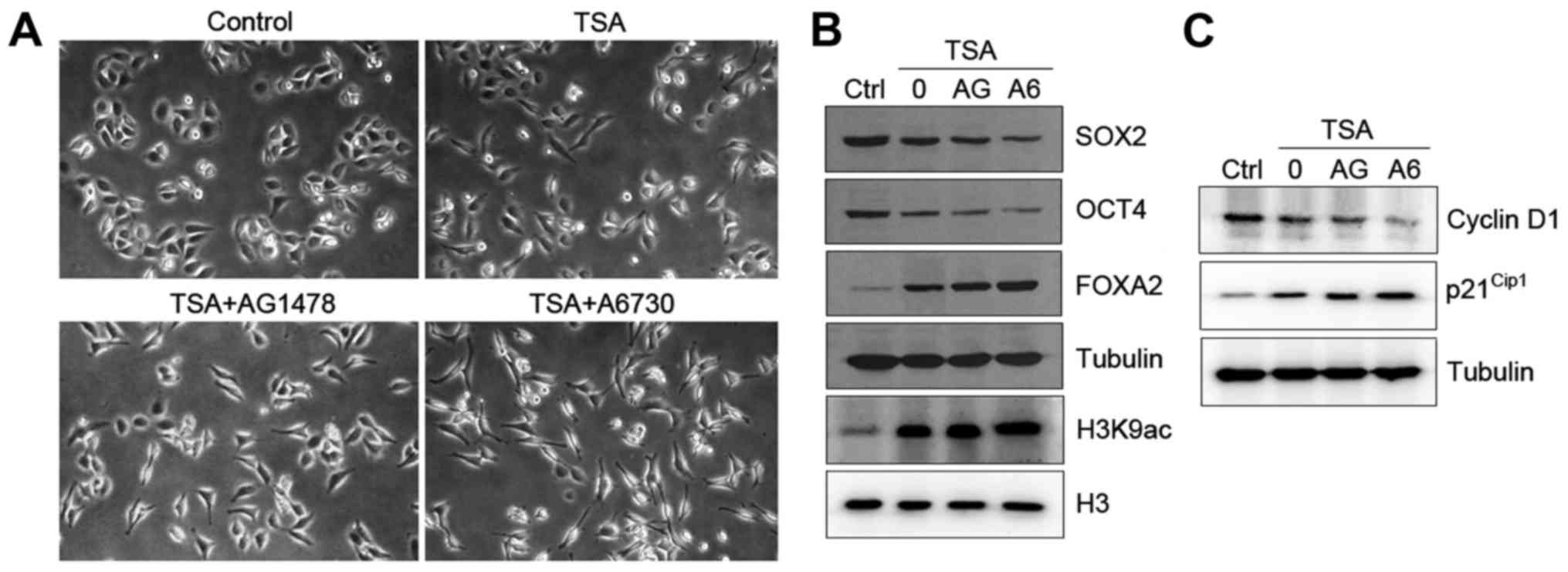

Inhibition of EGFR/AKT pathway

promotes TSA-induced differentiation of HO8910 cells

The above data indicate that TSA induces ovarian

cancer cell differentiation prompted us to test whether the

EGFR/AKT pathway was involved in this process. HO8910 cells treated

with either AG1478 or A6730 markedly promoted TSA-induced cell

differentiation with morphological changes (Fig. 4A). To determine the mechanism by

which inhibition of the EGFR/AKT pathway enhances cell

differentiation, we tested the expression of

differentiation-related genes in HO8910 cells. As expected,

combination of TSA and AG1478 or A6730 drastically reduced the

levels of SOX2 and OCT4 and increased the expression of FOXA2 in

the cells (Fig. 4B). Both

inhibitors also caused an increase in global levels of H3K9

acetylation (Fig. 4B).

Next, we tested the effect of TSA on cell cycle

regulation when EGFR/AKT signaling pathway was inhibited. Treatment

with AG1478 or A6730 decreased the levels of cyclin D1 and

increased the expression of p21Cip1 in HO8910 cells in

response to TSA (Fig. 4C).

Furthermore, combination treatment with TSA and AG1478 or A6730 led

to an accumulation of cells in G0/G1 phase in

comparison to TSA alone (Table

II). Collectively, our data suggest that TSA plays a role in

cell differentiation and that blockage of EGFR/AKT signaling

pathway enhances TSA-induced differentiation.

| Table II.Inhibition of EGFR/AKT signaling

pathway enhances TSA-induced G0/G1-phase cell

cycle arrest in HO8910 cells. |

Table II.

Inhibition of EGFR/AKT signaling

pathway enhances TSA-induced G0/G1-phase cell

cycle arrest in HO8910 cells.

| Groups | Control | TSA | TSA+AG1478 | TSA+A6730 |

|---|

|

G0/G1 |

58.3±1.2c |

79.7±2.4b |

85.6±1.1a |

89.5±2.5a |

| S |

27.1±1.3a |

3.9±0.7b |

3.8±1.6b |

2.6±1.8b |

Discussion

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression represents

a promising strategy for differentiation-based therapy (20). Histone acetylation is determined by

antagonistic actions of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) and HDACs

(21,22). A variety of HDAC inhibitors have

been demonstrated to induce differentiation in some solid tumors

(23). In this study, we

characterized the effect of TSA, one of the potent HDAC inhibitors,

on cell differentiation of ovarian tumors. We show that TSA

increases the levels of H3K9 acetylation, and induces cell

differentiation in HO8910 ovarian cancer cells with marked

morphological transformation. Molecular evidence for

differentiation is demonstrated by decreased expression of SOX2,

OCT4, and cyclin D1, and increased expression of FOXA2 and

p21Cip1. Significantly, blockage of EGFR/AKT signaling

pathway enhances the TSA-induced differentiation of HO8910

cells.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) that retain both the

self-renewal and differentiation, contributes to tumorigenesis and

chemotherapy resistance in malignancies (24,25).

The poor clinical outcome in patients with ovarian cancer may be

due to the existence of CSCs (24).

Overexpression of OCT4 and SOX2 is detected more frequently in

poorly differentiated cancers than in well-differentiated ones, and

is not detected in paraneoplastic tissues and benign tumors

(26,27). OCT4 is also overexpressed in CSCs

and is closely related to chemotherapy resistance (28), suggesting that OCT4 is a

pluripotency marker for CSCs. In addition, FOXA2 is a sensitive

marker of CSC and cancer cell differentiation (29,30),

and it was reported that apicidin, another HDAC inhibitor,

upregulates FOXA2 expression, leading to enhanced differentiation

of dopaminergic neurons (29). Our

current data demonstrated that TSA may promote cell differentiation

through upregulation of FOXA2 expression and downregulation of OCT4

and SOX2 expression. Strikingly, inhibition of EGFR/AKT signaling

pathway enhances the induction of cell differentiation and FOXA2

expression in response to TSA. These data suggest that the EGFR

signaling may overcome the TSA-induced cell differentiation through

downregulation of FOXA2 expression.

The Cdk inhibitor p21Cip1 plays a

critical role in mediating proliferation inhibition and acts as a

cell cycle arrest point (31).

There is accumulating evidence linking p21Cip1 to

carcinogenesis in many tumors, including ovarian cancer (32–34).

The increase in p21Cip1 could be associated with

increased cell cycle suppression by TSA in our study. The

concomitant reduction in cyclin D1 expression may cooperate with

induction of p21Cip1 to arrest the cell cycle, and thus

contribute to proliferation inhibition induced by TSA. The

upregulation of p21Cip1 might lead to preferential cell

cycle arrest upon TSA treatment.

HDACi in combination with chemotherapy has been

confirmed to give better clinical outcome than chemotherapy alone

(35,36). One potential strategy to increase

treatment efficacy is the combination of HDACi with other novel

agents. A recent study found that inhibition of EGFR/PI3K signaling

pathway enhanced TSA-induced cell death and inhibited cell

migration (37). The EGFR/PI3K

pathway also mediates Lewis(y)-induced cell proliferation (38). In this study, the reduction of cell

proliferation was additionally enhanced when TSA was combined with

the EGFR/AKT pathway inhibitors AG1478 or A6730, in accordance with

a previous report (37). This

finding suggests that EGFR signaling pathway could be a target for

improving therapeutic efficacy of TSA.

Here, we provide a link between the inhibition of

EGFR signaling and the differentiation effect of TSA on HO8910

cells. Our data indicate that TSA transactivates the EGFR signaling

pathway, which overcomes the TSA-induced differentiation of HO8910

cells via regulation of differentiation-related genes. Blockage of

the EGFR signaling pathway by AG1478 or A6730 enhances the

TSA-mediated cell differentiation. Although TSA is an epigenetic

regulator, the present study did not establish a mechanistic link

between TSA and epigenetic regulation of cell differentiation in

HO8910 cells. Further studies are needed to determine how TSA

activates the EGFR pathway in an epigenetic manner and how such

activation affects ovarican cancer cell differentiation.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by National Natural Science

Foundation of China (81170573).

References

|

1

|

Romero I and Bast RC Jr: Minireview: human

ovarian cancer: biology, current management, and paths to

personalizing therapy. Endocrinology. 153:1593–1602. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Lopez J, Banerjee S and Kaye SB: New

developments in the treatment of ovarian cancer - future

perspectives. Ann Oncol. 24:(Suppl 10). X69–X76. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kim A, Ueda Y, Naka T and Enomoto T:

Therapeutic strategies in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 31:142012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ferlay J, Parkin DM and Steliarova-Foucher

E: Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008.

Eur J Cancer. 46:765–781. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Leitao MM Jr and Chi DS: Surgical

management of recurrent ovarian cancer. Semin Oncol. 36:106–111.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Leszczyniecka M, Roberts T, Dent P, Grant

S and Fisher PB: Differentiation therapy of human cancer: Basic

science and clinical applications. Pharmacol Ther. 90:105–156.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Huang ME, Ye YC, Chen SR, Chai JR, Lu JX,

Zhoa L, Gu LJ and Wang ZY: Use of all-trans retinoic acid in the

treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia. Blood. 72:567–572.

1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kinjo K, Kizaki M, Muto A, Fukuchi Y,

Umezawa A, Yamato K, Nishihara T, Hata J, Ito M, Ueyama Y, et al:

Arsenic trioxide (As2O3)-induced apoptosis

and differentiation in retinoic acid-resistant acute promyelocytic

leukemia model in hGM-CSF-producing transgenic SCID mice. Leukemia.

14:431–438. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Yamashita Y, Shimada M, Harimoto N,

Rikimaru T, Shirabe K, Tanaka S and Sugimachi K: Histone

deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A induces cell-cycle

arrest/apoptosis and hepatocyte differentiation in human hepatoma

cells. Int J Cancer. 103:572–576. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Rosato RR and Grant S: Histone deacetylase

inhibitors in clinical development. Expert Opin Investig Drugs.

13:21–38. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Buchwald M, Krämer OH and Heinzel T: HDACi

- targets beyond chromatin. Cancer Lett. 280:160–167. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Eickhoff B, Germeroth L, Stahl C, Köhler

G, Rüller S, Schlaak M and van der Bosch J: Trichostatin A-mediated

regulation of gene expression and protein kinase activities:

Reprogramming tumor cells for ribotoxic stress-induced apoptosis.

Biol Chem. 381:1127–1132. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Freudlsperger C, Burnett JR, Friedman JA,

Kannabiran VR, Chen Z and Van Waes C: EGFR-PI3K-AKT-mTOR signaling

in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas: Attractive targets for

molecular-oriented therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 15:63–74.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lassus H, Sihto H, Leminen A, Joensuu H,

Isola J, Nupponen NN and Butzow R: Gene amplification, mutation,

and protein expression of EGFR and mutations of ERBB2 in serous

ovarian carcinoma. J Mol Med (Berl). 84:671–681. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shao G, Wang J, Li Y, Liu X, Xie X, Wan X,

Yan M, Jin J, Lin Q, Zhu H, et al: Lysine-specific demethylase 1

mediates epidermal growth factor signaling to promote cell

migration in ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 5:153442015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Li Y, Wan X, Wei Y, Liu X, Lai W, Zhang L,

Jin J, Wu C, Shao Q, Shao G, et al: LSD1-mediated epigenetic

modification contributes to ovarian cancer cell migration and

invasion. Oncol Rep. 35:3586–3592. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Kaestner KH: The FoxA factors in

organogenesis and differentiation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 20:527–532.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Jeong JW, Kwak I, Lee KY, Kim TH, Large

MJ, Stewart CL, Kaestner KH, Lydon JP and DeMayo FJ: Foxa2 is

essential for mouse endometrial gland development and fertility.

Biol Reprod. 83:396–403. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Akimoto T, Hunter NR, Buchmiller L, Mason

K, Ang KK and Milas L: Inverse relationship between epidermal

growth factor receptor expression and radiocurability of murine

carcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 5:2884–2890. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Wang LT, Liou JP, Li YH, Liu YM, Pan SL

and Teng CM: A novel class I HDAC inhibitor, MPT0G030, induces cell

apoptosis and differentiation in human colorectal cancer cells via

HDAC1/PKCδ and E-cadherin. Oncotarget. 5:5651–5662. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Liu H, Wu H, Wang Y, Wang Y, Wu X, Ju S

and Wang X: Inhibition of class II histone deacetylase blocks

proliferation and promotes neuronal differentiation of the

embryonic rat neural progenitor cells. Acta Neurobiol Exp (Wars).

72:365–376. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kretsovali A, Hadjimichael C and

Charmpilas N: Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cell pluripotency,

differentiation, and reprogramming. Stem Cells Int.

2012:1841542012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Cruz FD and Matushansky I: Solid tumor

differentiation therapy - is it possible? Oncotarget. 3:559–567.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Ciurea ME, Georgescu AM, Purcaru SO,

Artene SA, Emami GH, Boldeanu MV, Tache DE and Dricu A: Cancer stem

cells: Biological functions and therapeutically targeting. Int J

Mol Sci. 15:8169–8185. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kwon MJ and Shin YK: Regulation of ovarian

cancer stem cells or tumor-initiating cells. Int J Mol Sci.

14:6624–6648. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li X, Wang J, Xu Z, Ahmad A, Li E, Wang Y,

Qin S and Wang Q: Expression of Sox2 and Oct4 and their clinical

significance in human non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Mol Sci.

13:7663–7675. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ge N, Lin HX, Xiao XS, Guo L, Xu HM, Wang

X, Jin T, Cai XY, Liang Y, Hu WH, et al: Prognostic significance of

Oct4 and Sox2 expression in hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma.

J Transl Med. 8:942010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lin H, Sun LH, Han W, He TY, Xu XJ, Cheng

K, Geng C, Su LD, Wen H, Wang XY, et al: Knockdown of OCT4

suppresses the growth and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells

through inhibition of the AKT pathway. Mol Med Rep. 10:1335–1342.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Bang SY, Kwon SH, Yi SH, Yi SA, Park EK,

Lee JC, Jang CG, You JS, Lee SH and Han JW: Epigenetic activation

of the Foxa2 gene is required for maintaining the potential of

neural precursor cells to differentiate into dopaminergic neurons

after expansion. Stem Cells Dev. 24:520–533. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Zhang X, Lu F, Wang J, Yin F, Xu Z, Qi D,

Wu X, Cao Y, Liang W, Liu Y, et al: Pluripotent stem cell protein

Sox2 confers sensitivity to LSD1 inhibition in cancer cells. Cell

Rep. 5:445–457. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Sherr CJ and Roberts JM: CDK inhibitors:

Positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes

Dev. 13:1501–1512. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Weiss RH: p21Waf1/Cip1 as a

therapeutic target in breast and other cancers. Cancer Cell.

4:425–429. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Jackson RJ, Adnane J, Coppola D, Cantor A,

Sebti SM and Pledger WJ: Loss of the cell cycle inhibitors

p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1) enhances tumorigenesis in knockout mouse

models. Oncogene. 21:8486–8497. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bali A, O'Brien PM, Edwards LS, Sutherland

RL, Hacker NF and Henshall SM: Cyclin D1, p53, and

p21Waf1/Cip1 expression is predictive of poor clinical

outcome in serous epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

10:5168–5177. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Ahrens TD, Timme S, Hoeppner J, Ostendorp

J, Hembach S, Follo M, Hopt UT, Werner M, Busch H, Boerries M, et

al: Selective inhibition of esophageal cancer cells by combination

of HDAC inhibitors and Azacytidine. Epigenetics. 10:431–445. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Shi YK, Li ZH, Han XQ, Yi JH, Wang ZH, Hou

JL, Feng CR, Fang QH, Wang HH, Zhang PF, et al: The histone

deacetylase inhibitor suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid induces

growth inhibition and enhances taxol-induced cell death in breast

cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 66:1131–1140. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zhou C, Qiu L, Sun Y, Healey S, Wanebo H,

Kouttab N, Di W, Yan B and Wan Y: Inhibition of EGFR/PI3K/AKT cell

survival pathway promotes TSA's effect on cell death and migration

in human ovarian cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 29:269–278.

2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Liu JJ, Lin B, Hao YY, Li FF, Liu DW, Qi

Y, Zhu LC, Zhang SL and Iwamori M: Lewis(y) antigen stimulates the

growth of ovarian cancer cells via regulation of the epidermal

growth factor receptor pathway. Oncol Rep. 23:833–841.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|