Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fourth most commonly

diagnosed malignancy worldwide and is characterized by an adverse

clinical outcome (1–3). Due to the lack of effective biomarkers

for an early diagnosis, the 5-year survival rate of patients with

advanced GC is only 5–15% (4,5).

Surgical resection may be the only hope for advanced-stage GC

patients, but has a high rate of recurrence (6,7).

Therefore, it is imperative to explore novel biomarkers and

therapeutic targets that may be helpful in developing targeted

therapies for GC.

Orthodenticle homolog 1 (OTX1), an OTX family (OTX1,

OTX2, OTX3 and CRX) protein, is a transcription factor that

specifically binds to TAATCC/T elements on target genes (8). OTX1 is comprised of a bicoid-like

homeodomain and belongs to the homeobox (HB) family of genes.

Previous studies have revealed that OTX1 plays a crucial role in

the development of the brain, sensory organs, early human fetal

retina and mammary gland (9–11).

OTX1 has been recently reported to be frequently overexpressed in

various cancers, including medulloblastomas, breast and colorectal

cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (12,13),

indicating that OTX1 may be a key regulator in the development and

progression of human carcinogenesis. Further studies have revealed

that OTX1 promotes tumor proliferation and migration in colorectal

cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (14,15).

However, the role and underlying mechanism of OTX1 in the

development and progression of GC remains to be elucidated.

In the present study, we observed that OTX1 was

overexpressed in GC samples and that there was a significant

correlation between a high expression level of OTX1 and poor

prognosis in GC patients. We investigated the effects of OTX1

silencing on GC cell proliferation, migration and invasion.

Furthermore, cell cycle distribution and cell apoptosis were

examined following OTX1 knockdown. This study indicated that OTX1

could be a therapeutic target for the treatment of GC.

Materials and methods

Differential expression analysis of

OTX1 using UALCAN

The expression data of OTX1 in GC and normal samples

were retrieved and analyzed using the online web portal UALCAN

(http://ualcan.path.uab.edu) (16) based on The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA) level 3 RNA-seq and clinical data from stomach

adenocarcinomas.

Patients and specimens

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Haimen People's Hospital, and all the patients

provided written informed consent. Cancer tissue specimens were

obtained from 50 GC patients who underwent radical gastrectomy

without prior radiotherapy or chemotherapy between June 2010 and

July 2013 at the Department of General Surgery, Haimen People's

Hospital (Jiangsu, China). In addition, 50 patients with benign

gastric diseases who underwent simple polypectomy via endoscopy

were included as controls. All diagnoses of GC, gastric polyps and

lymph node metastasis were confirmed by histopathological

examination. The tissue specimens were fixed in 4% formalin

immediately after removal and were embedded in paraffin for

immunohistochemical staining. Each sample was frozen and stored at

−80°C. Among the 50 GC cases, there were 34 males and 16 females

with ages ranging from 44 to 90 years (mean age, 68 years). All the

specimens were confirmed by pathological diagnoses and were staged

according to the 7th AJCC-TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors.

The median follow-up period was 32.90 months (range, 2.93–43.83

months).

Immunohistochemical analysis and

evaluation of OTX1 expression

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using a

standard immunoperoxidase staining procedure. OTX1 expression in

benign and malignant specimens was evaluated according to methods

described by Terrinoni et al (13). Sections were semi-quantitatively

scored for the extent of immunoreactivity as follows: 0, 0%

immunoreactive cells; 1, <5% immunoreactive cells; 2, 5–50%

immunoreactive cells; and 3, >50% immunoreactive cells.

Additionally, the staining intensity was semi-quantitatively scored

as 0 (negative), 1 (weak), 2 (intermediate), or 3 (strong). The

final immunoreactivity score was defined as the sum of both

parameters, and the samples were grouped as having negative (0),

weak (1–2), moderate (3), or strong (4–6)

staining. For statistical purposes, only the final immunoreactivity

scores of the moderate and strong groups were considered positive,

and the other final scores were considered negative.

Cell culture

The SGC-7901 and MGC-803 cell lines were purchased

from the Shanghai Cell Bank, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai,

China). Cells were cultured with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

(DMEM; HyClone Laboratories; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan,

UT, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life

Technologies, Paisley, UK) and antibiotics (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) in a humidified incubator containing 5%

CO2 at 37°C.

Lentivirus-mediated RNA

interference

The shRNA targeted to OTX1 and a negative control

shRNA (shNC) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas,

TX, USA). Recombinant lentiviruses expressing OTX1-shRNA (shOTX1)

or shNC were provided by Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd. (Shanghai,

China). For the construction of stable cell lines, the cells were

selected with puromycin for 7 days after infection with a

lentivirus for 72 h. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain

reaction (RT-qPCR) and western blot analyses were performed to

determine the expression level of OTX1.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells using

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.,

Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Subsequently, 1 µg of total RNA was used to synthesize first-strand

cDNA using a reverse transcription reagent kit (Takara

Biotechnology, Co., Ltd., Dalian, China). The RT-qPCR assay was

performed with SYBR Green Premix Ex Taq (Takara Biotechnology)

using the following thermocycling conditions: 95°C for 30 sec,

followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec, and

the data were analyzed using the ∆∆Cq method with GAPDH as an

internal control. The primer sequences were as follows: OTX1

forward, 5′-CTGCTCTTCCTCAATCAATGG-3′ and reverse,

5′-ACCCTGACTTGTCTGTTTCC-3′; GAPDH forward,

5′-TGCACCACCAACTGCTTAGC-3′ and reverse,

5′-GGCATGGACTGTGGTCATGAG-3′. The experiment was repeated three

times.

Cell proliferation assay

SGC-7901 and MGC-803 cells were infected with shNC

or shOTX1 for 72 h. Cell proliferation was determined using Cell

Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Tokyo,

Japan). Briefly, 2×103 SGC-7901 or MGC-803 cells/well

were seeded into 96-well plates. At each of the indicated

time-points (0, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 days), 10 µl of CCK-8 reagent was

added to each well, followed by incubation for 2 h at 37°C. The

optical density (OD) values at 450 nm for each well were determined

using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA,

USA).

Colony formation assay

SGC-7901 and MGC-803 cells were seeded into 6-well

plates at a density of 400 cells/well following infection with an

shNC- or shOTX1-expressing virus. The cells were then cultured for

14 days, and the media were replaced every three days. The cells

were stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) for 25 min after fixation with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 20 min. The plates were washed with

ddH2O three times and air-dried. Finally, colonies with

>50 cells were captured with an ×200 magnification using an

inverted microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) and

counted manually.

Migration/invasion assay

Matrigel-coated Transwell chambers were used for the

invasion assay, and uncoated Transwell chambers (8-µm pore; Corning

Inc., Lowell, MA, USA) were used for the migration assay. SGC-7901

and MGC-803 cells were infected with the desired virus and were

trypsinized after 72 h of infection. Subsequenlty,

1.2×105 SGC-7901 cells or 3×104 MGC-803 cells

were seeded into the upper chamber of an 8-µm pore-size insert with

or without Matrigel, while the lower chamber was filled with DMEM

containing 10% FBS. After a 48-h culture period, the cells were

fixed and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. Cells that

had passed through the 8-µm pore were counted in five random fields

using a light microscope (Leica Microsystems) at an ×100

magnification. Three independent experiments were performed.

Wound healing assay

The wound healing assay was performed as described

by Wang et al (17).

Briefly, GC cells infected with the corresponding virus were seeded

into 6-well plates to form a single confluent cell layer. The

plates were scratched with 200-µl pipettes to form a wound within

the confluent cell layer. The cells were then incubated in

serum-free medium for 0, 24 or 72 h. The movement of cells into the

scratched area was photographed using the inverted Leica DMI3000B

microscope (Leica Microscopes).

Cell cycle analysis

For the cell cycle assays, SGC-7901 or MGC-803 cells

were collected via trypsinization and fixed in ice-cold 70% ethanol

overnight. The cells were then washed three times with PBS and

incubated with 10 mg/ml RNase and 1 mg/ml propidium iodide (PI)

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck) at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. All the

samples were assessed using flow cytometry (BD Biosciences,

Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and were analyzed using CellQuest

acquisition software version 3.3 (BD Biosciences). Each experiment

was performed in triplicate.

Cell apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was detected using the Annexin V/PI

apoptosis kit following the manufacturer's instructions

(Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Briefly, GC cells were

harvested by EDTA-free trypsinization and were washed twice with

ice-cold PBS. Subsequently, the cells were resuspended in 100 µl of

binding buffer at a density of 1×106 cells/ml, followed

by the addition of 5 µl of Annexin V-FITC and 5 µl of PI for 15 min

at room temperature in the dark. Finally, 400 µl of binding buffer

was added to each sample, and the cells were immediately analyzed

by flow cytometry. The experiment was repeated three times. The

experiment was repeated three times. The perentages of Q3 quadrant

(Annexin V−/PI−), Q4 quadrant (Annexin

V+/PI−) and Q2 quadrant (Annexin

V+/PI+) were as following: 96.93±0.75,

1.3±0.06 and 0.8±0.05% in the shNC group and 85.73±0.31, 3.7±0.16

and 4±0.21% in the shOTX1 group in SGC-7901 cells; 96.7±0.85,

1.5±0.08 and 0.9±0.04% in the shNC group and 88.63±2.71, 4.8±0.32

and 4.2±0.13% in the shOTX1 group in MGC-803 cells.

Western blot analysis

The total protein content of the GC cells was

extracted using ice-cold radio-immunoprecipitation assay buffer

(RIPA; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) supplemented with PMSF

and was incubated on ice for 30 min. Following centrifugation at

10,000 × g, the supernatants were harvested, and the protein

concentration was determined using the BCA protein assay kit

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Equal amounts of protein (30

µg) were separated via 10% SDS-PAGE and were transferred onto

polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF) (EMD Millipore,

Billerica, MA, USA). Then, the PVDF membranes were blocked with 5%

fat-free milk (GuangMing, Shanghai, China) and incubated at 4°C

overnight with the following primary antibodies: Anti-OTX1 (1:500;

cat. no. sc-517000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-GAPDH (1:1,000;

cat. no. ab181602; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-cleaved caspase-3

(1:1,000; cat. no. 9661), anti-cleaved PARP (1:1,000; cat. no.

5625), anti-Bax (1:1,000; cat. no. 14796), anti-N-cadherin

(1:1,000; cat. no. 13116), anti-Bcl-2 (1:1,000; cat. no. 3498; all

from Cell Signaling Technology), anti-proliferating cell nuclear

antigen (PCNA) (1:1,000; cat. no. ab92552; Abcam), anti-Slug

(1:1,000; cat. no. ab27568; Abcam), anti-vimentin (1:2,000; cat.

no. ab92547; Abcam) and anti-Snail (1:1,000; cat. no. 3879; Cell

Signaling Technology). The membranes were then incubated with goat

anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (1:5,000; cat. no. ab6721; Abcam)

after washing three times with TBST buffer. The protein bands were

visualized using ECL detection reagents (EMD Millipore). GAPDH

served as the loading control.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were calculated using the

SPSS 18.0 software for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). An

independent Student's t-test was used to compare the means of two

groups. Pearson's χ2 test was used to analyze the

association of OTX1 expression with the clinicopathological

parameters. Kaplan-Meier plots and log-rank tests were used for the

survival analysis. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional

hazards regression models were used to analyze the independent

prognostic factors. The data were presented as the mean ± SD.

Student's t-test (two-tailed) was used to analyze continuous

variables. The results were considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference when P<0.05.

Results

Clinical significance of OTX1 in GC

tissues

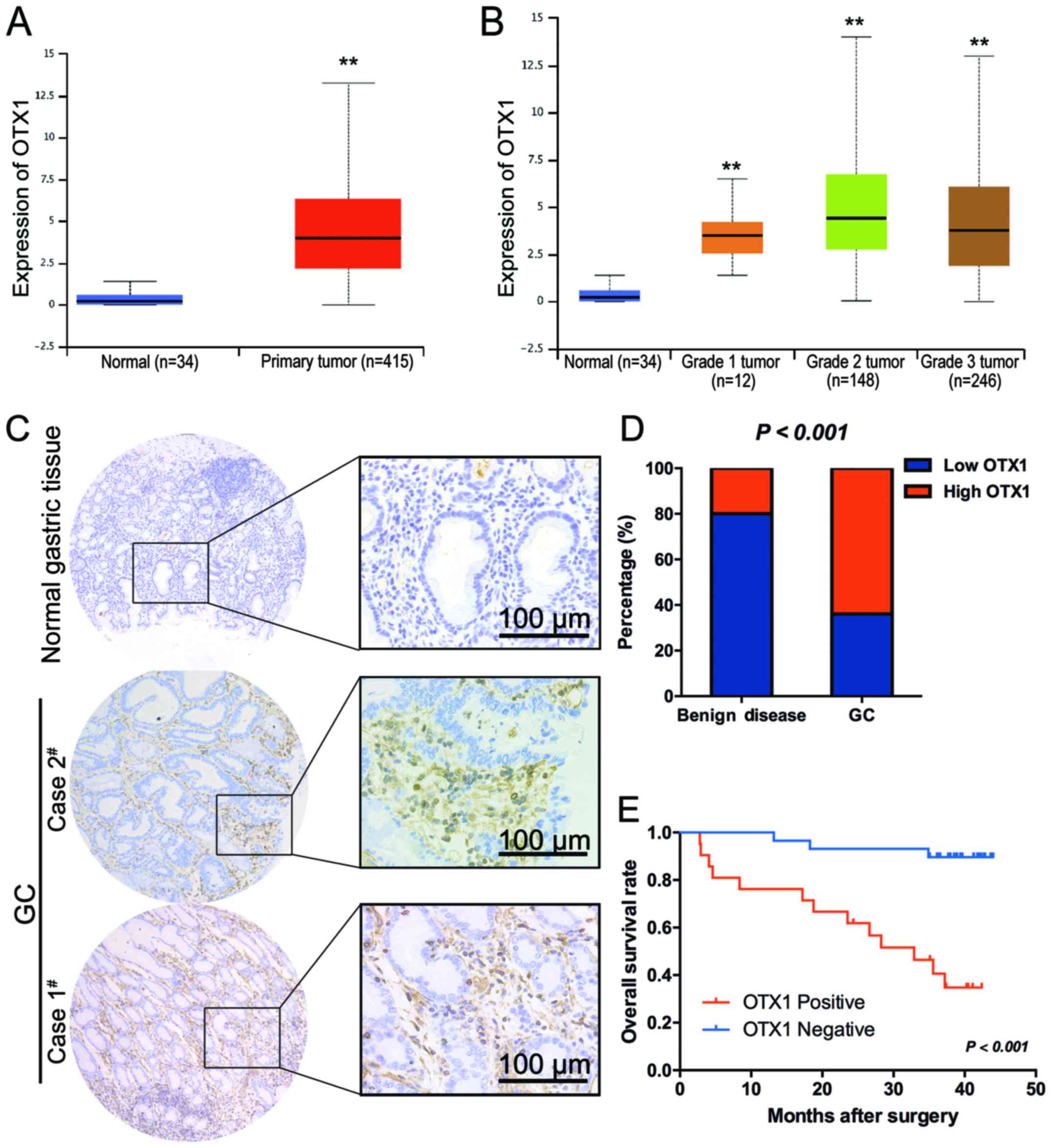

Using microarray analysis, a previous study revealed

that OTX1 was upregulated in GC tissues (18), indicating an oncogenic role for OTX1

in GC. To further confirm this result in a large cohort of patient

samples, we retrieved data from TCGA database and analyzed the

expression of OTX1 in stomach adenocarcinomas, comprised of 415 GC

tissues and 34 non-cancerous gastric tissues, using the online web

portal UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu) (16). As clearly indicated in Fig. 1A, OTX1 was significantly upregulated

in GC tissues compared with normal tissues. In addition, OTX1 had

the highest expression level in grade II tumors (Fig. 1B).

Furthermore, the protein expression levels of OTX1

were determined by immunohistochemistry in 50 samples of archived

paraffin-embedded GC tissues and 50 gastric polyp epithelial

tissues (Fig 1C). The expression of

OTX1 was significantly higher in the tumor tissues than in the

benign disease tissues (P<0.001) (Fig. 1D). A clinicopathological association

study of 50 GCs revealed that OTX1 was significantly associated

with the Borrmann type (P=0.012) and lymph node metastasis

(P<0.001) (Table I), indicating

that OTX1 may play a role in metastasis. Notably, positivity for

OTX1 was significantly correlated with a shorter overall survival

(OS) time (log rank, 16.61; P<0.001) (Fig. 1E). A multivariate Cox regression

analysis further revealed that OTX1 was an independent prognostic

marker for the OS time of GC patients (hazard ratio, 0.126; 95%

confidence interval, 0.035–0.448; P=0.001) (Table II).

| Table I.Association of the expression of OTX1

with the clinicopathological characteristics of GC patients. |

Table I.

Association of the expression of OTX1

with the clinicopathological characteristics of GC patients.

|

|

| Relative OTX1

expression |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | Category | Negative (n=29) | Positive (n=21) | χ2 | P-value |

|---|

| Age | <60 years | 13 | 6 | 1.366 | 0.242 |

|

| ≥60 years | 16 | 15 |

|

|

| Sex | Male | 18 | 16 | 1.116 | 0.291 |

|

| Female | 11 | 5 |

|

|

| Location of

tumor | Upper stomach | 2 | 0 | 2.236 | 0.525 |

|

| Middle stomach | 8 | 4 |

|

|

|

| Lower stomach | 17 | 15 |

|

|

|

| Mixed | 2 | 2 |

|

|

| Borrmann type | Early stage | 8 | 0 | 8.812 |

0.012a |

|

| I+II type | 8 | 4 |

|

|

|

| III+IV type | 13 | 17 |

|

|

| Histological

differentiation | Well | 4 | 0 | 5.991 | 0.05 |

|

| Moderate | 9 | 3 |

|

|

|

| Poor | 16 | 18 |

|

|

| Tumor invasion

(AJCC) | Tis-T2 | 17 | 0 | 18.652 |

<0.001a |

|

| T3-T4 | 12 | 21 |

|

|

| Lymph node

metastasis | Yes | 13 | 20 | 13.973 |

<0.001a |

|

| No | 16 | 1 |

|

|

| TNM stage

(AJCC) | I–II | 25 | 4 | 22.552 |

<0.001a |

|

| III–IV | 4 | 17 |

|

|

| Table II.Univariate and multivariate analyses

of clinical variables contributing to OS. |

Table II.

Univariate and multivariate analyses

of clinical variables contributing to OS.

|

| Univariate

analysis | Multivariate

analysis |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (<60 vs. ≥60

years) | 3.004

(0.847–10.657) | 0.074 | – | – |

| Sex (male vs.

female) | 0.786

(0.250–2.473) | 0.680 | – | – |

| Location of tumor

(upper or middle stomach vs. lower stomach) | 0.373

(0.134–1.039) | 0.049 | – | – |

| Histological

differentiation (well or moderate vs. poor) | 2.209

(0.732–6.665) | 0.334 | – | – |

| Tumor invasion

(AJCC) (Tis-T2 vs. T3-T4) | 9.625

(1.263–73.330) |

0.007a | 2.884

(0.255–32.578) | 0.392 |

| Lymph node

metastasis (yes vs. no) | 4.122

(0.929–18.295) |

0.043a | 1.085

(0.144–8.154) | 0.937 |

| TNM stage (AJCC)

(I–II vs. III–IV) | 5.113

(1.619–16.145) | 0.002 | 1.413

(0.283–7.059) | 0.673 |

| Type of surgery

(curative resection vs. palliative) | 0.431

(0.097–1.921) | 0.255 | – | – |

| OTX1 expression in

tumor (negative vs. positive) | 0.126

(0.035–0.448) |

<0.001a | 0.126

(0.035–0.448) | 0.001 |

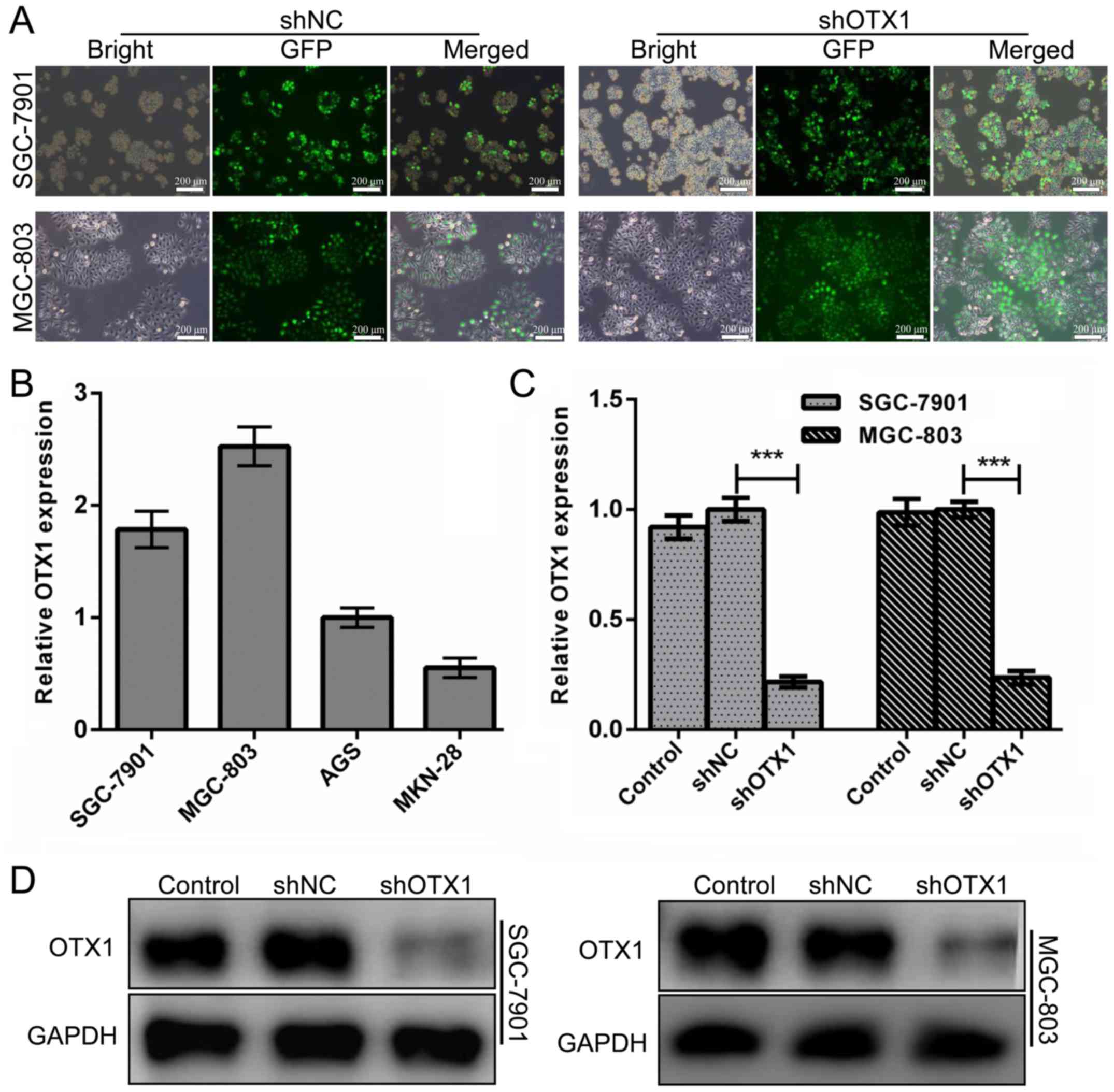

Lentivirus-mediated knockdown of OTX1

in GC cell lines

To explore the biological role of OTX1 in the

tumorigenesis of GC, we determined the mRNA expression of OTX1 in

four GC cell lines and found that SGC-7901 and MGC-803 cells harbor

relatively higher expression of OTX1 (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we suppressed OTX1

with a specific shRNA lentiviral vector in SGC-7901 and MGC-803

cells. As displayed in Fig. 2A, the

infection efficiency was greater than 90%, as determined by the

EGFP signal. Real-time PCR and western blot assays at 72 h

following infection revealed that the expression of OTX1 in both

cell lines was significantly downregulated at the mRNA and protein

levels (Fig. 2C and D,

P<0.01).

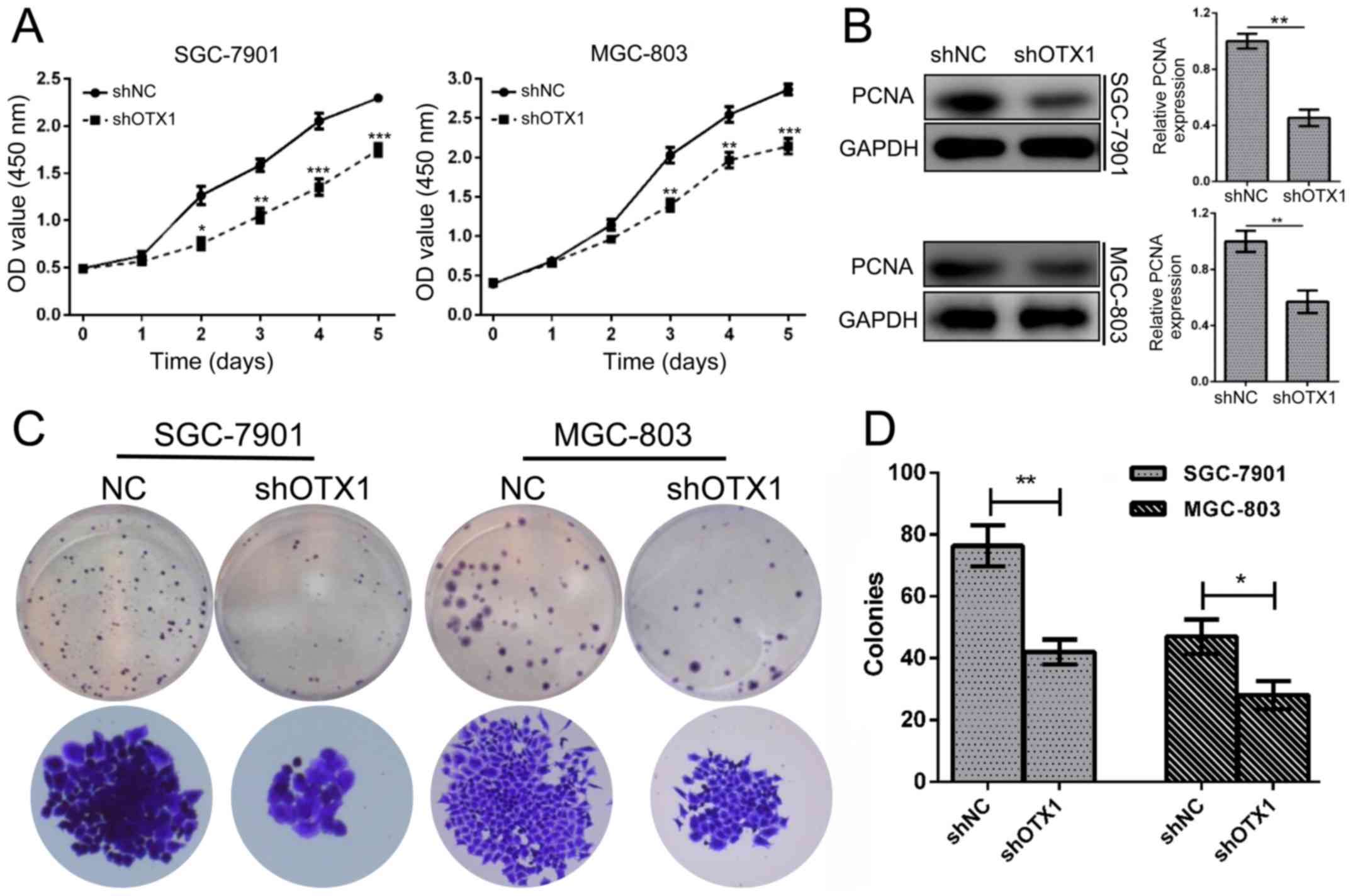

Depletion of OTX1 significantly

suppresses the proliferation of GC cells

To determine the effect of OTX1 on GC cell

proliferation, a CCK-8 assay was conducted in SGC-7901 and MGC-803

cells following infection with shOTX1 or shNC. The results revealed

that OTX1 knockdown significantly inhibited the proliferation of GC

cells (P<0.001, P<0.01, P<0.05; Fig. 3A). Consistently, the knockdown of

OTX1 markedly reduced the expression of PCNA (Fig. 3B). In addition, the colony formation

assay revealed that shOTX1-infected cells formed smaller and fewer

colonies than the shNC-infected cells (Fig. 3C and D; P<0.01). Collectively,

these data indicated that OTX1 promoted the proliferation of GC

cells.

Effect of OTX1 knockdown on the cell

cycle of GC cells

To further investigate the role for OTX1 in tumor

growth, a cell cycle analysis was performed using flow cytometry.

SGC-7901 and MGC-803 cells infected with shOTX1 exhibited a notable

increase in the percentage of cells in the

G0/G1 phase compared with the shNC groups

(Fig. 4A and B), indicating that

OTX1 knockdown led to a G0/G1-phase arrest.

Consistently, cyclin D1 protein expression was markedly

downregulated in the shOTX1-infected GC cells (Fig. 4C). Collectively, these results

indicated that the knockdown of OTX1 inhibited cell proliferation

by inducing a G0/G1-phase arrest.

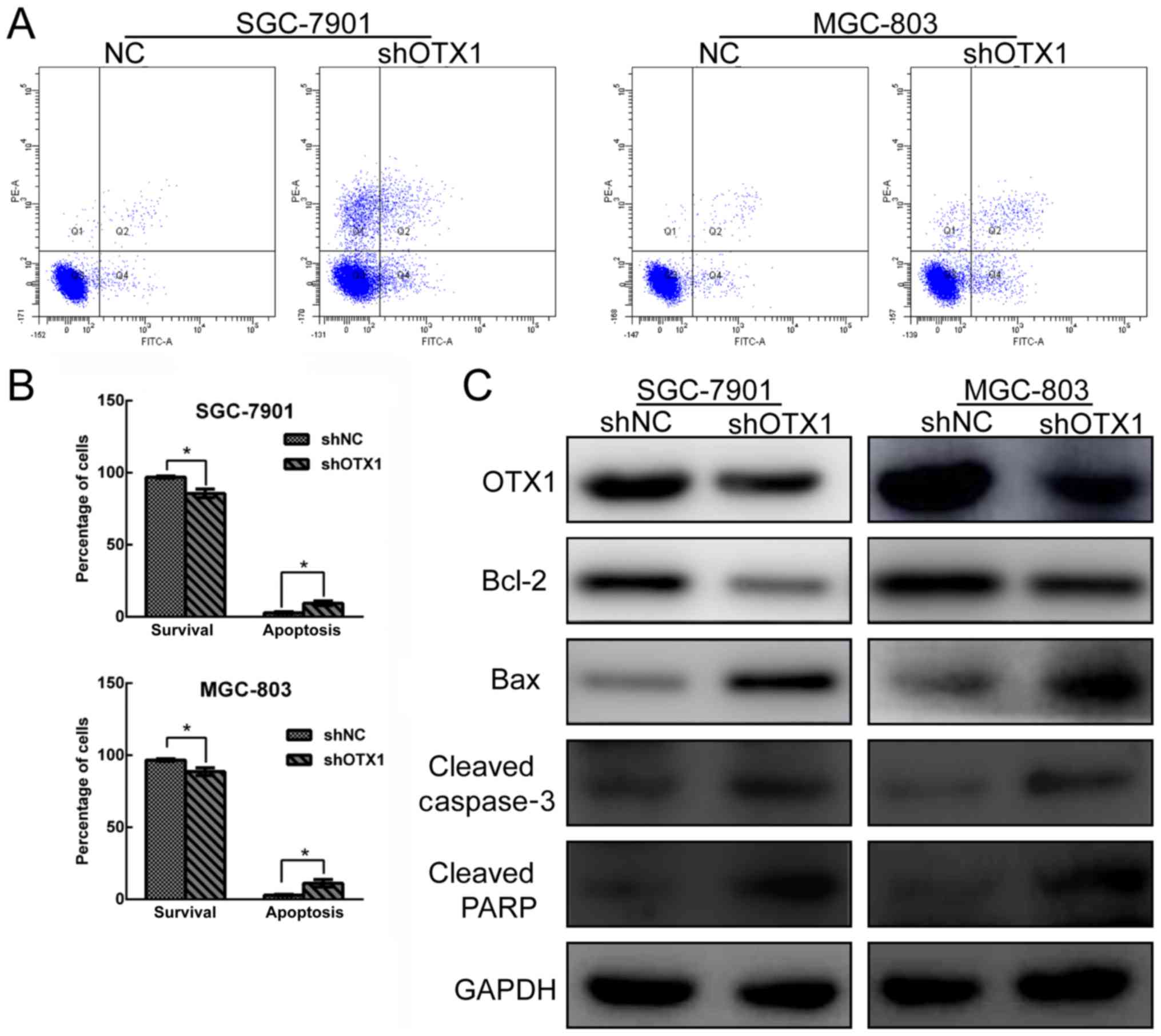

Effect of OTX1 on GC cell

apoptosis

The effect of OTX1 knockdown on cell apoptosis was

determined by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining using flow cytometry. As

revealed in Fig. 5A and B,

OTX1-silenced GC cells exhibited an increased rate of apoptosis

compared with the shNC groups. Subsequently, a western blot assay

was used to further examine the effect of OTX1 on the expression of

apoptosis-related proteins. As displayed in Fig. 5C, the depletion of OTX1 resulted in

the upregulation of cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP and Bax

expression and the reduction of Bcl-2 expression, further

supporting the observation that OTX1 knockdown induced GC cell

apoptosis. Collectively, these data indicated that OTX1 knockdown

induced cell apoptosis by modulating apoptosis-related

proteins.

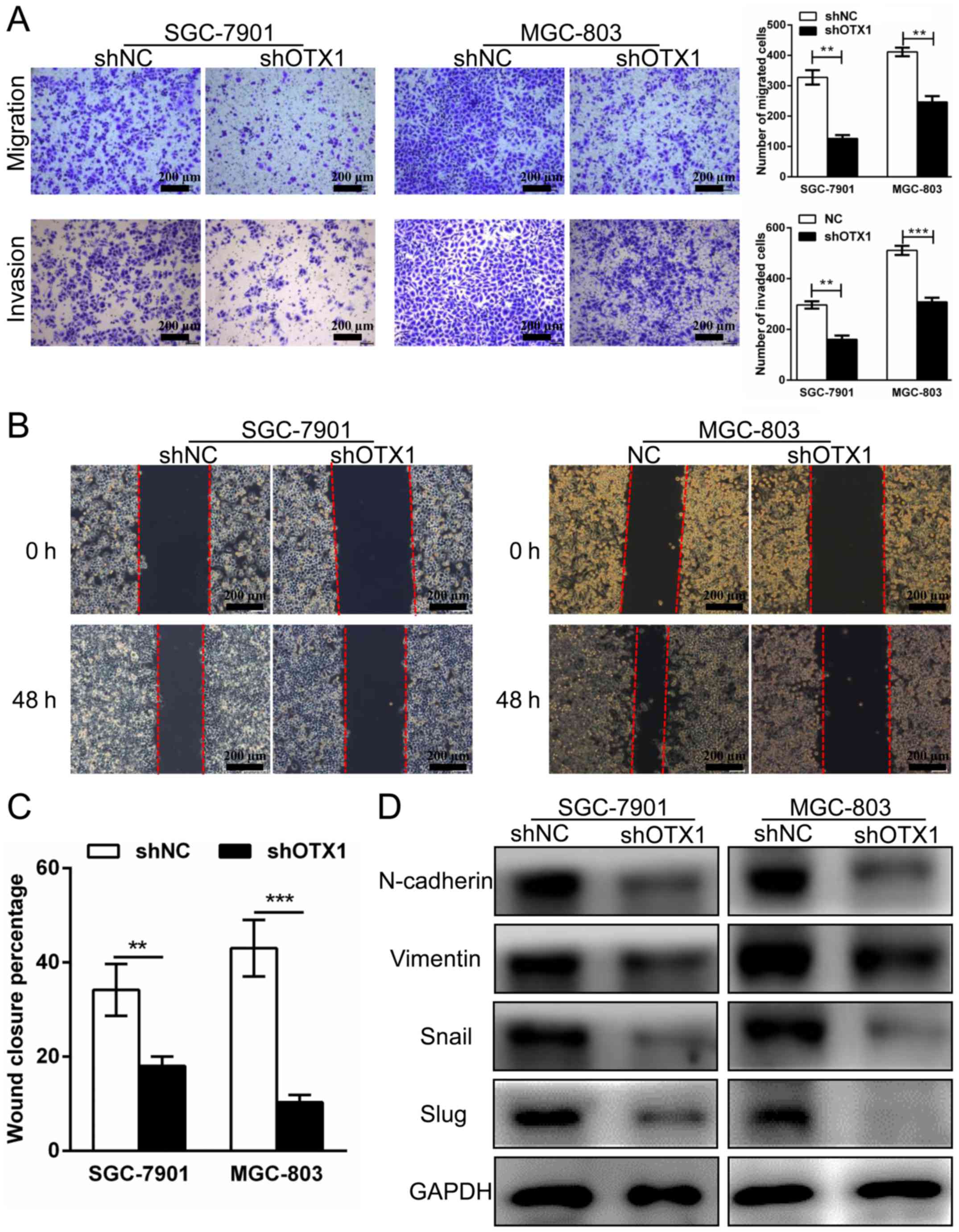

Effect of OTX1 on GC cell migration

and invasion

To investigate whether OTX1 contributed to the

migration and invasion of GC cells, wound healing, Transwell

migration and Matrigel invasion assays were performed. As displayed

in Fig. 6A, the knockdown of OTX1

significantly attenuated cell migration and invasive abilities

compared with those in the control group. In addition, we observed

that the percentage of wound closure in the OTX1-silenced cells was

markedly decreased compared with the shNC-infected cells,

indicating that the migration of the SGC-7901 and MGC-803 cells was

inhibited by OTX1 silencing (Fig. 6B

and C). Subsequently, we used western blot analysis to examine

whether the expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition

(EMT)-related proteins was altered following OTX1 knockdown.

Consistent with our previous observations, we found that the

OTX1-silenced cells exhibited a reduction in the expression of

N-cadherin, vimentin, Snail and Slug (Fig. 6D). In summary, these results

indicated that OTX1 promoted GC cell migration and invasion by

altering the expression of EMT-related proteins.

Discussion

The overexpression of OTX1 is a common event in

various types of cancer, including medulloblastomas, breast and

colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (12–15).

The overexpression of OTX1 in GC tissues was reported in a

genome-wide expression profiling analysis (18). Our clinical association study

revealed that the overexpression of OTX1 was significantly

associated with the Borrmann type, lymph node metastasis, and a

shorter OS time in GC patients. Cox proportional hazard regression

analysis further identified OTX1 as an independent factor for a

poor prognosis, demonstrating that OTX1 overexpression in GC may

serve as a biomarker for early detection and precise prognoses.

However, to our knowledge, the biological role of OTX1 in GC cells

and the underlying mechanisms of this factor remain largely

unknown. In the present study, we provided evidence that OTX1 plays

an important role in GC carcinogenesis.

OTX1 has been previously only implicated in

embryonic development. Recently, increasing evidence has

demonstrated that OTX1 participates in the progression of numerous

malignancies (9,12–15).

In breast cancer cells, it was revealed that p53 directly induced

the expression of OTX1 by acting on the OTX1 promoter (13). The present study demonstrated that

the silencing of OTX1 expression inhibited GC cell proliferation

and colony formation. In addition, we observed that the expression

of PCNA, a proliferation marker, was reduced after the OTX1

knockdown. The dysregulation of the cell cycle is a hallmark of

tumorigenesis. We determined with the cell cycle distribution

analysis that the lack of OTX1 led to a G0/G1

phase arrest. Furthermore, we found that the expression of cyclin

D1, a key protein that promoted the G0/G1 to

S phase transition (19), decreased

when OTX1 was silenced. Collectively, our results demonstrated that

the knockdown of OTX1 induced a G0/G1 arrest

by downregulating cyclin D1.

It is well known that the deregulation of apoptosis

contributes to cancer development. Caspase-3 is a key executioner

caspase, and caspase-3 activation leads to the cleavage of PARP,

which is considered a central indicator of apoptosis (20). In this study, we confirmed that the

knockdown of OTX1 resulted in higher apoptosis rates in SGC-7901

and MGC-803 cells than those in the control cells. Furthermore, the

knockdown of OTX1 significantly increased the expression of Bax,

cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved PARP, while such a knockdown

downregulated the expression of Bcl-2. However, which pathway is

involved in the shOTX1-induced apoptosis remains to be

investigated. A previous study demonstrated that OTX1 contributed

to HCC progression possibly by regulating the ERK/MAPK pathway

(15). It would be interesting to

examine whether the ERK/MAPK pathway is also affected by OTX1 in GC

cells.

The EMT, characterized by the loss of epithelial

cell polarity, plays a crucial role in cancer metastasis (21,22).

Our results indicated that the knockdown of OTX1 inhibited

migration and invasion by suppressing the expression of mesenchymal

markers (N-cadherin and vimentin) and EMT-related transcription

factors (Snail and Slug). These findings demonstrated that OTX1

promoted the metastasis of GC cells by inducing the EMT process.

Further studies will be required to clarify the specific target

genes of OTX1 in tumorigenesis.

In conclusion, our results demonstrated that OTX1

enhanced tumor growth and induced EMT in GC cells, supporting the

oncogenic role of OTX1 in GC progression. Our results indicated

that OTX1 may serve as a potential target for the treatment of GC.

However, more detailed studies are required to further illustrate

the role of OTX1 in gastric carcinoma cells.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are

available from the corresponding author upon reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

YDY supervised and directed this study. SCQ and ZZ

performed most of the experiments. SCQ and YDY contributed to the

project design. JXS and XHX collected the tumor samples and the

clinical data. JY, JJL and BC contributed to the cell culture and

RNA extraction. GDZ and XYW helped with manuscript preparation.

SCQ, ZZ and YDY analysed the data and wrote this manuscript. All

authors read and approved the manuscript and agree to be

accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the

accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Haimen People's Hospital, and all the patients

provided written informed consent.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wang J, Yu JC, Kang WM and Ma ZQ:

Treatment strategy for early gastric cancer. Surg Oncol.

21:119–123. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 64:9–29. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward

E and Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin.

61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nonoshita T, Otsuka S, Inagaki M and

Iwagaki H: Complete response obtained with S-1 plus CDDP therapy in

a patient with multiple liver metastases from gastric cancer.

Hiroshima J Med Sci. 64:65–69. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tong W, Ye F, He L, Cui L, Cui M, Hu Y, Li

W, Jiang J, Zhang DY and Suo J: Serum biomarker panels for

diagnosis of gastric cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 9:2455–2463.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chang JS, Kim KH, Keum KC, Noh SH, Lim JS,

Kim HS, Rha SY, Lee YC, Hyung WJ and Koom WS: Recursive partition

analysis of peritoneal and systemic recurrence in patients with

gastric cancer who underwent D2 gastrectomy: Implications for

neoadjuvant therapy consideration. J Surg Oncol. 114:859–864. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Thrumurthy SG, Chaudry MA, Chau I and

Allum W: Does surgery have a role in managing incurable gastric

cancer? Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 12:676–682. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Klein WH and Li X: Function and evolution

of Otx proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 258:229–233. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Omodei D, Acampora D, Russo F, De Filippi

R, Severino V, Di Francia R, Frigeri F, Mancuso P, De Chiara A,

Pinto A, et al: Expression of the brain transcription factor OTX1

occurs in a subset of normal germinal-center B cells and in

aggressive non-hodgkin lymphoma. Am J Pathol. 175:2609–2617. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Larsen KB, Lutterodt M, Rath MF and Møller

M: Expression of the homeobox genes PAX6, OTX2, and OTX1 in the

early human fetal retina. Int J Dev Neurosci. 27:485–492. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pagani IS, Terrinoni A, Marenghi L, Zucchi

I, Chiaravalli AM, Serra V, Rovera F, Sirchia S, Dionigi G, Miozzo

M, et al: The mammary gland and the homeobox gene Otx1. Breast J.

16 Suppl:S53–S56. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

de Haas T, Oussoren E, Grajkowska W,

Perek-Polnik M, Popovic M, Zadravec-Zaletel L, Perera M, Corte G,

Wirths O, van Sluis P, et al: OTX1 and OTX2 expression correlates

with the clinicopathologic classification of medulloblastomas. J

Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 65:176–186. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Terrinoni A, Pagani IS, Zucchi I,

Chiaravalli AM, Serra V, Rovera F, Sirchia S, Dionigi G, Miozzo M,

Frattini A, et al: OTX1 expression in breast cancer is regulated by

p53. Oncogene. 30:3096–3103. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Yu K, Cai XY, Li Q, Yang ZB, Xiong W, Shen

T, Wang WY and Li YF: OTX1 promotes colorectal cancer progression

through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 444:1–5. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li H, Miao Q, Xu CW, Huang JH, Zhou YF and

Wu MJ: OTX1 contributes to hepatocellular carcinoma progression by

regulation of ERK/MAPK pathway. J Korean Med Sci. 31:1215–1223.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya

SAH, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi BVSK and

Varambally S: UALCAN: A portal for facilitating tumor subgroup gene

expression and survival analyses. Neoplasia. 19:649–658. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Wang N, Wang Q, Shen D, Sun X, Cao X and

Wu D: Downregulation of microRNA-122 promotes proliferation,

migration, and invasion of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by

activating epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Onco Targets Ther.

9:2035–2047. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mao Y, Zhao Q, Yin S, Ding X and Wang H:

Genome-wide expression profiling and bioinformatics analysis of

deregulated genes in human gastric cancer tissue after gastroscopy.

Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 14:e29–e36. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Ezhevsky SA, Ho A, Becker-Hapak M, Davis

PK and Dowdy SF: Differential regulation of retinoblastoma tumor

suppressor protein by G(1) cyclin-dependent kinase complexes in

vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 21:4773–4784. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Boulares AH, Yakovlev AG, Ivanova V,

Stoica BA, Wang G, Iyer S and Smulson M: Role of poly(ADP-ribose)

polymerase (PARP) cleavage in apoptosis. Caspase 3-resistant PARP

mutant increases rates of apoptosis in transfected cells. J Biol

Chem. 274:22932–22940. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Nieto MA: Epithelial-mesenchymal

transitions in development and disease: Old views and new

perspectives. Int J Dev Biol. 53:1541–1547. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Kalluri R and Weinberg RA: The basics of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 119:1420–1428.

2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|