Introduction

Gap junctions are special regions adjoining cell

membranes and are direct pathways for the exchange of signals among

cardiac myocytes. Gap junctions mediate current flow, thereby

coordinating the spread of excitation and subsequent contraction

throughout the myocardium (1). The

electrical conduction velocity in the region of gap junctions is

faster compared to that elsewhere (2). It was previously suggested that

changes in the gap junctions in morbid heart tissue, collectively

referred to as gap junction remodeling, appear to be associated

with the incidence of arrhythmias (3–7).

Heptanol is commonly used as a gap junction

inhibitor in several experiments. Previous studies demonstrated

that regional perfusion with heptanol may decrease the conduction

velocity and induce reentrant arrhythmias (8,9).

However, little is known regarding the effects of heptanol on the

arrhythmias induced by ischemia. The aim of this study was to

investigate the effects of heptanol on ventricular arrhythmias

induced by ischemia and evaluate the changes in connexin 43 (Cx43),

the major gap junction protein, in the ischemic myocardium. As

heptanol may act on sodium and calcium channels (9–11), it

may also affect the action potential. Therefore, the cardiac

electrophysiological properties, such as heart rate (HR), PR

interval, QT interval and monophasic action potential duration at

90% repolarization (MAPD90) were also assessed.

Materials and methods

Animals

A total of 60 adult male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats,

weighing 0.2–0.3 kg, were provided by the Experimental Animal

Center of Tongji Hospital (Shanghai, China). All the animal

experiments were conducted in compliance with the Guide for the

Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Reasearch Council,

1996).

Isolated heart preparation

The SD rats were anesthetized with 1% pentobarbital

(0.5 ml/kg) and heparinized via intraperitoneal injection (50

IU/kg). The hearts were quickly excised, mounted on a Langendorff

apparatus via the aorta and perfused with Krebs-Henseleit (K-H)

buffer (Shanghai Chemical Reagent Co., Shanghai, China) at a

constant perfusion pressure of 90 cmH2O. The K-H

solution consisted of 118.6 mmol/l NaCl, 25 mmol/l

NaHCO3, 4.7 mmol/l KCl, 1.18 mmol/l

KH2SO4, 1.2 mmol/l MgSO4, 2.5

mmol/l CaCl2 and 11.1 mmol/l glucose, was gassed with

95% O2 and 5% CO2 (pH 7.4) and maintained at

37±1°C. Bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO,

USA) was added to the perfusate at a concentration of

6.013×10−4 M (40 mg/l) to improve the stability of the

hearts.

All the measurements were performed after an initial

stabilization period of at least 15 min of perfusion with stable

electrophysiological signals, temperature and coronary flow.

The hearts were randomly divided into 5 groups as

follows: i) control group: the hearts were subjected to normal

perfusion with K-H buffer solution for 45 min; ii) ischemia group:

following perfusion for 15 min with K-H buffer solution, the hearts

were subjected to regional ischemia by ligating the left anterior

descending coronary artery (LAD) close to its origin for 30 min;

iii–v) heptanol groups: the hearts were pretreated with 0.1, 0.3

and 0.5 mM heptanol, respectively, for 15 min prior to the

induction of ischemia. Heptanol was dissolved directly in the

perfusate at different concentrations and perfused into the

isolated hearts.

Electrophysiological measurements

An epicardial electrogram was recorded using two

silver electrodes (with a diameter of 0.3 mm) placed on the surface

of the left and right ventricles. The MAPDs were recorded by

another two electrodes placed on the surface of the left ventricle

near the septal and the aortic cannulae. The epicardial

electrograms and MAPD were amplified and analyzed using Medlab

computer software (Nanjing Madease Science and Technology Co.,

Ltd., Nanjing, China).

The parameters, including HR, PR interval, QT

interval and MAPD, were recorded at baseline (15 min prior to

ischemia; 0 min) and at 10 min (Is10 min), 20 min (Is20 min) and 30

min (Is30 min) after the induction of ischemia. During this period,

VT and VF were recorded. VT was defined as a run of ventricular

beats lasting >1 min.

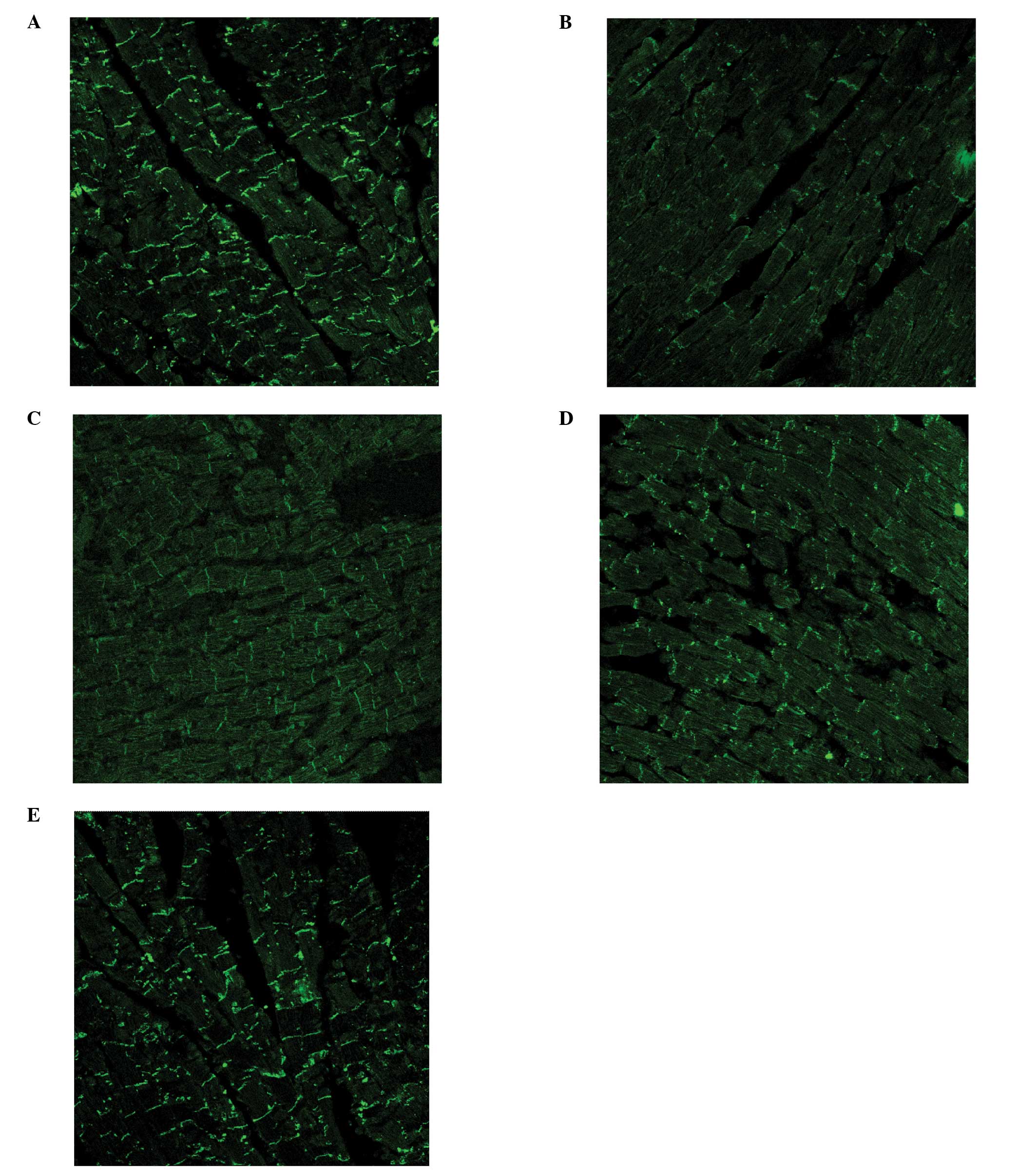

Immunofluorescence analysis

At the end of the experiment, 5 hearts from each

group were selected and perfused with 1% Evans blue dye. The

non-blue parts were re-stained with triphenyltetrazolium chloride

(TTC; Shanghai Chemical Reagent Co.). The sections that stained

with TTC were identified as ischemic and were fixed in 10% neutral

buffered formalin for immunofluorescence (12,13). A

rabbit polyclonal antibody (Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA,

USA) directed against Cx43 was used as the primary antibody

(dilution, 1:100). FITC-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG was used as

the secondary antibody (dilution, 1:100). Images were captured with

a TCS SP2 confocal microscope (Leica, Mannheim, Germany) at a

magnification of ×400, using a 40× oil immersion lens. Five areas

were analyzed in each heart, for a total of 25 test areas in each

group.

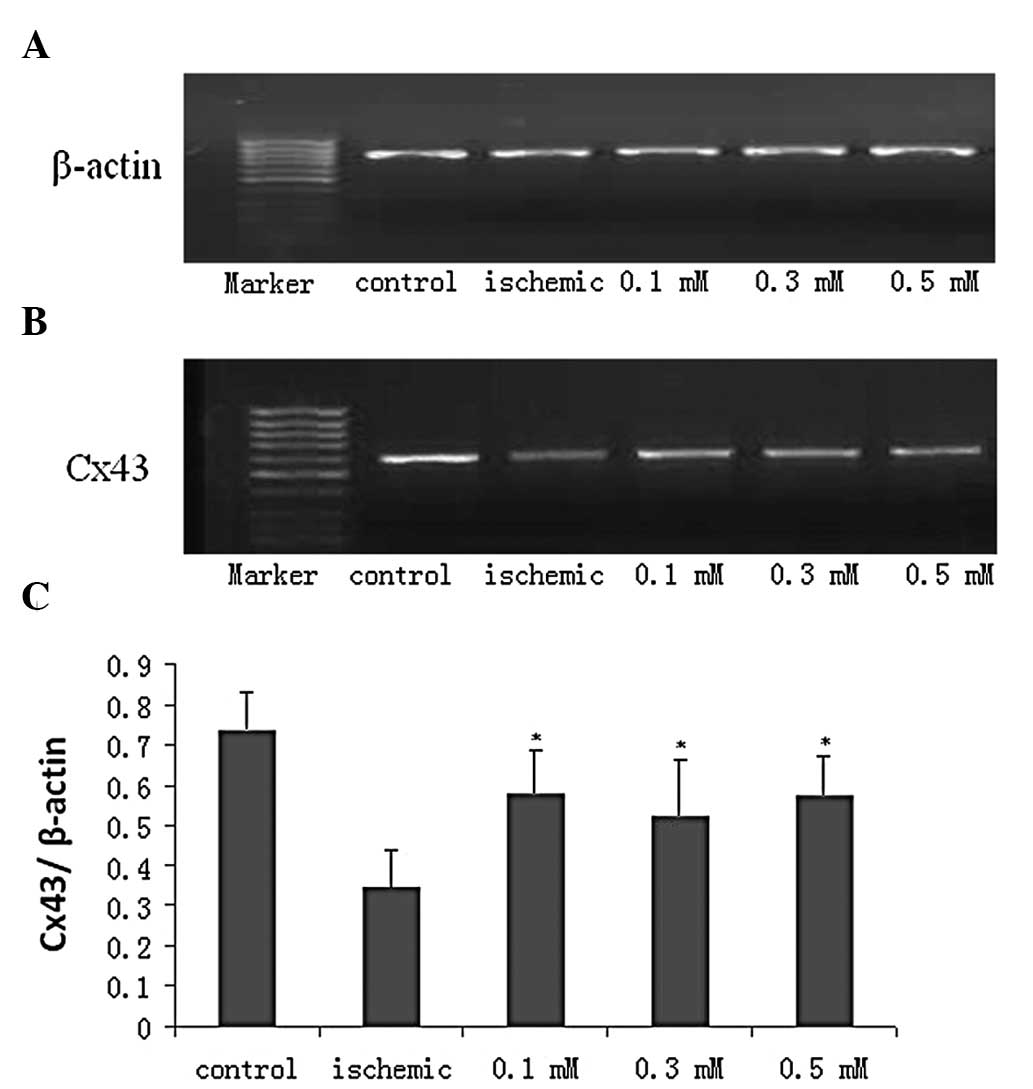

Semi-quantitative reverse

transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

RNA samples (2 μg per experiment) were extracted

from the ischemic myocardium. RNA extraction, first-strand

complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis and DNA amplification were

performed as previously described, with minor modifications

(13). Two pairs of primers

designed with Primer 5.0 software were used to amplify a 588-bp

product of Cx43 and a 770-bp product of β-actin, which was used as

control (Table I). The reaction

system (50 μl) contained 33.75 μl H2O, 5 μl 10X buffer,

200 μM dNTP mixture, 1.875 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μl Taq

DNA polymerase, 2 μl of the pair primers and 4 μl cDNA. The PCR

samples were subjected to initial denaturation for 2 min at 95°C,

30 cycles of 30 sec at 95°C and 30 sec at 60°C, followed by a final

extension at 72°C for 5 min. These procedures were completed in a

PTC-100 automated thermocycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA,

USA).

| Table IOligonucleotide primers used for

RT-PCR analysis. |

Table I

Oligonucleotide primers used for

RT-PCR analysis.

| Target | Primer sequence

(5′→3′) | Size (bp) |

|---|

| Cx43 | F: TTG TTT CTG TCA

CCA GTA AC | 588 |

| R: GAT GAG GAA GGA

AGA GAA GC | |

| β-actin | F: CGT GGC GTT TAC

GAA GAT | 770 |

| R: ACC CAG ATC ATG

TTT GAG ACC | |

The RT-PCR products were visualized on 1.5% agarose

gels electrophoresed in 1X Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. After 25 min,

the gels were placed in a solution containing 0.5 μg/ml ethidium

bromide and then into a UV transilluminator (Shanghai Qin Xiang

Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The results of

the immunofluorescence and RT-PCR analyses were assessed with Leica

Qwin image software (Leica Microsystems).

Statistical analyses

The values are expressed as means ± SE. The

myocardial electrical characteristics and Cx43 protein and mRNA

expression were compared among groups by the analysis of repeated

measures. The occurance of ventricular arrhythmias among groups was

assessed by the Fisher’s exact test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Experimental hearts

The total number of rats used in this experiment was

60. Of the 60 hearts, 8 were discarded due to ligation failure. The

hearts that completed the entire protocol (n=52) included 11 hearts

in the ischemia group, 10 hearts in the 0.1 mM heptanol group, 10

hearts in the 0.3 mM heptanol group, 9 hearts in the 0.5 mM

heptanol group and 12 hearts in the control group without

ligation.

Electrophysiological parameters

The electrophysiological parameters are presented in

Table II. Ischemia was shown to

decrease the QT interval and MAPD90 and prolong the PR interval;

however, it did not affect HR. Heptanol decreased HR following LAD

ligation (Fig. 1A), whereas it

prolonged the PR interval, QT interval and MAPD90 following LAD

ligation, particularly at the concentration of 0.5 mM (Fig. 1B–D).

| Table IIElectrophysiological parameters in the

ischemic group. |

Table II

Electrophysiological parameters in the

ischemic group.

| | Time points

(min) |

|---|

| |

|

|---|

| Parameters | Groups | 0 | Is10a | Is20b | Is30c |

|---|

| HR | Control | 238±54 | 233±41 | 218±35 | 210±53 |

| Ischemic | 225±42 | 231±51 | 211±84 | 181±84 |

| PR interval | Control | 36.4±5.2 | 40.2±5.3 | 35.9±4.3 | 41.2±6.3 |

| Ischemic | 33.3±5.9 | 35.5±8.4 | 67.1±12.3d | 76.6±10.3d |

| QT interval | Control | 220±48 | 200±58 | 198±33 | 201±57 |

| Ischemic | 224±45 | 221±68 | 92±25d | 101±33d |

| MAPD90 | Control | 89.3±25.3 | 88.5±20.3 | 75.6±20.8 | 77.6±25.3 |

| Ischemic | 86.7±23.2 | 78.4±18.9 | 49.6±18.9d | 55.2±12.3d |

Incidence of VT and VF

Heptanol decreased the percentage of ventricular

arrhythmias induced by ischemia. The percentage of ventricular

arrhythmias was 45% in the ischemia group, 10% in the 0.1 mM group

and 0% in the 0.3 and 0.5 mM groups (P<0.05) (Table III).

| Table IIIIncidence of ventricular arrhythmia

induced by regional ischemia. |

Table III

Incidence of ventricular arrhythmia

induced by regional ischemia.

| Groups | No. | VT and VF

incidence | % |

|---|

| Ischemic | 11 | 5 | 45 |

| Heptanol |

| 0.1 mM | 10 | 1 | 10a |

| 0.3 mM | 10 | 0 | 0a |

| 0.5 mM | 9 | 0 | 0a |

Immunofluorescence staining results

The level of the Cx43 protein, as evaluated by

immunofluorescence microscopy, was found to be lower in the

ischemic myocardium compared to that in normal myocardium (Fig. 2A and B). Heptanol was able to partly

reverse this downregulation induced by ischemia, with the level of

the Cx43 protein being 1,706±397 μM2 in the control

group, 561±147 μM2 in the ischemic group, 1,027±215

μM2 in the 0.1 mM group, 1,112±301 μM2 in the

0.3 mM group and 1,179±425 μM2 in the 0.5 mM group

(P<0.05). There was no significant difference among the treated

groups (Fig. 2C–E).

mRNA expression of Cx43

The results of RT-PCR were expressed by the ratio of

Cx43 to β-actin. The mRNA level of Cx43 was found to be lower in

the ischemia group compared to that in the control group and

heptanol was able to partly reverse this downregulation (Fig. 3A–C).

Discussion

In this study, we observed that VT and VF occurred

in almost half of the cases in the ischemic group and in only one

of the 29 cases in the treated groups, suggesting that heptanol

significantly decreased the incidence of VT and VF induced by

regional ischemia. Previous studies demonstrated that the slower

electrical conduction in the ischemic myocardium may lead to

reentrant arrhythmia (14,15). Heptanol was shown to reduce the

electrical conduction velocity by decreasing the function of gap

junctions in all the regions of the myocardium (16). The difference in the reduction of

the velocity between normal and ischemic regions in the heart may

decrease the incidence of reentrant arrhythmia.

Heptanol was shown to depress the inward

Na+ current (17), which

may explain the prolongation of the QT interval and MAPD90. In the

ischemic myocardium, the shorter repolarization duration may lead

to the development of reentrant arrhythmia (14). Thus, the decrease in repolarization

dispersion between the ischemic and the normal myocardium caused by

heptanol may be responsible for the decreased occurrence of

ventricular arrhythmia.

Additionally, heptanol reduced the HR and PR

interval, suggesting that it may affect the function of the sinus

and atrioventricular nodes.

We observed that the expression of Cx43 in the

ischemic myocardium was lower compared to that in the normal

myocardium, indicating that ischemia may damage gap junctions

(18,19). A number of factors may be involved

in this change, such as the decrease in the pH and the accumulation

of free radicals and lipid metabolites. The reduction of gap

junctions in the ischemic myocardium eventually results in a

decrease in the conduction velocity. The difference in conduction

between the ischemic and the normal myocardium may be an important

factor leading to the development of reentrant arrhythmias. In the

present experiment, heptanol was able to partly reverse the

reduction of Cx43 and may participate in the prevention of ischemic

arrhythmias. The result of the RT-PCR revealed that the

upregulation of Cx43 by heptanol occurred at the mRNA level.

Heptanol is liposoluble; thus, it may cross the cell membrane to

regulate the transcription of Cx43.

In conclusion, the gap junction inhibitor heptanol

decreases the incidence of VT and VF induced by regional ischemia

through altering the myocardial electrophysiological properties and

the transcription of Cx43.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81300150).

References

|

1

|

Qi X, Varma P, Newman D and Dorian P: Gap

junction blockers decrease defibrillation thresholds without

changes in ventricular refractoriness in isolated rabbit hearts.

Circulation. 104:1544–1549. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Moreno AP, Rook MB, Fishman GI and Spray

DC: Gap junction channels: distinct voltage-sensitive and

-insensitive conductance states. Biophys J. 67:113–119. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yu ZB and Sheng JJ: Remodeling of cardiac

gap junctions and arrhythmias. Acta Physiologica Sinica.

63:586–592. 2011.(In Chinese).

|

|

4

|

Delmar M and Makita N: Cardiac connexins,

mutations and arrhythmias. Curr Opin Cardiol. 27:236–241. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Palatinus JA, Rhett JM and Gourdie RG: The

connexin43 carboxyl terminus and cardiac gap junction organization.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1818:1831–1843. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Severs NJ, Bruce AF, Dupont E and Rothery

S: Remodelling of gap junctions and connexin expression in diseased

myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 80:9–19. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dupont E, Matsushita T, Kaba RA, et al:

Altered connexin expression in human congestive heart failure. J

Mol Cell Cardiol. 33:359–371. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Ohara T, Qu Z, Lee MH, et al: Increased

vulnerability to inducible atrial fibrillation caused by partial

cellular uncoupling with heptanol. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol.

283:H1116–H1120. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Tse G, Hothi SS, Grace AA and Huang CL:

Ventricular arrhythmogenesis following slowed conduction in

heptanol-treated, Langendorff-perfused mouse hearts. J Physiol Sci.

62:79–92. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dorian P, Wang M, David I and Feindel C:

Oral clofilium produces sustained lowering of defibrillation energy

requirements in a canine model. Circulation. 83:614–621. 1991.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Labhasetwar V, Underwood T, Heil RW Jr, et

al: Epicardial administration of ibutilide from polyurethane

matrices: effects on defibrillation threshold and

electrophysiologic parameters. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 24:826–840.

1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Saffitz JE, Green KG, Kraft WJ, et al:

Effects of diminished expression of connexin 43 on gap junction

number and size in ventricular myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ

Physiol. 278:H1662–H1670. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kwong KF, Schuessler RB, Green KG, et al:

Differential expression of gap junction proteins in the canine

sinus node. Circ Res. 82:604–612. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Li Y, Xue Q, Ma J, et al: Effects of

imidapril on heterogeneity of action potential and calcium current

of ventricular myocytes in infarcted rabbits. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

25:1458–1463. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Saffitz JE and Kléber AG: Gap junctions,

slow conduction, and ventricular tachycardia after myocardial

infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 60:1111–1113. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Callans DJ, Moore EN and Spear JF: Effect

of coronary perfusion of heptanol on conduction and ventricular

arrhythmias in infarcted canine myocardium. J Cardiovasc

Electrophysiol. 7:1159–1171. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Li F, Sugishita K, Su Z, et al: Activation

of connexin-43 hemichannels can elevate [Ca2+]i and

[Na+]i in rabbit ventricular myocytes during metabolic

inhibition. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 33:2145–2155. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Sánchez JA, Rodríguez-Sinovas A,

Fernández-Sanz C, et al: Effects of a reduction in the number of

gap junction channels or in their conductance on

ischemia-reperfusion arrhythmias in isolated mouse hearts. Am J

Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 301:H2442–2453. 2011.

|

|

19

|

Wit AL and Peters NS: The role of gap

junctions in the arrhythmias of ischemia and infarction. Heart

Rhythm. 9:308–311. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|