Introduction

With a rapidly aging population, osteoporosis is a

significant concern in Japan. While it is asymptomatic,

osteoporosis progresses gradually, leading to hip and lumbar

fractures, which may require extended nursing care and threaten

life expectancy (1). Therefore,

prevention of osteoporosis is important and the efficacy of

bisphosphonates in osteoporosis treatment has been supported by

previous studies (2). However, side

effects of bisphosphonate use are gastrointestinal (GI) disorders

(3,4). In

the ‘super-aging’ Japanese society, consumption of non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin increases with the

greater incidence of joint, ischemic heart and cerebrovascular

diseases, with NSAID-induced GI disorders becoming an increasing

concern (5,6). In addition, gastric acid secretion in

Japanese patients has gradually increased due to a trend towards

Westernized eating habits (7) and a

decrease in Helicobacter pylori infections, with the number

of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients also increasing

rapidly (8). Proton pump inhibitors

(PPIs) are key first-line therapeutic strategies for the treatment

of NSAID-induced ulcers and GERD (9).

PPIs are often administered as a long-term treatment, and it is

common for PPIs to be used concomitantly with bisphosphonates. A

previous study suggested that PPI use was associated with a

dose-dependent loss of the anti-fracture efficacy of alendronate

(AD) (10). However, there are few

prospective studies that investigate the efficacy of AD on lumbar

bone mineral density (BMD) in osteoporotic patients using

concomitant PPIs. The aim of the present study was to investigate

the efficacy of AD on lumbar BMD in osteoporotic patients using

concomitant PPIs, comparing the effects versus alfacalcidol (AC) in

a prospective, randomized, open-label, comparative study.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present study was conducted as a prospective,

randomized, open-label, active control, comparative, single-center

study. From 2009 until 2013 at Juntendo University Hospital (Tokyo,

Japan), osteoporotic patients (age, ≥50 years) who were using PPIs

were enrolled in the study. After assignment to the AC (1 µg/day)

or AD (35 mg/week) groups, the patients were followed up for one

year of treatment. The AD group patients took the medication in the

early morning (after an overnight fast) with a glass of plain

water, and were instructed to remain upright for ≥30 min before

consuming the first food of the day. Patients from the two groups

were prohibited from taking any other medication affecting bone or

calcium metabolism during the treatment period. Patient profiles

[age, gender, body mass index (BMI), alcohol consumption, smoking,

comorbidities (type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension)] and

ongoing concomitant medications [calcium channel blockers (CCBs),

low-dose aspirin (LDAA), and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A

(HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors] were evaluated. BMI was calculated

as body weight divided by the square of body height in meters

(kg/m2). Patients that had used standard doses of CCBs,

LDAA, or HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors for >6 months were

identified as users of that specific therapy. We defined the cases

that used the usual dose of PPIs (10 mg rabeprazole or 20 mg

omeprazole or 30 mg lansoprazole) for >6 months as users of that

specific therapeutic strategy. The study was conducted in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Juntendo

University Ethics Committee approved this study protocol (reference

no. 207-028) and patients signed an Ethics Committee-approved

informed consent document.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with osteoporosis were selected for the

present study, however, certain individuals were excluded according

to the following criteria: Patients who were currently or

previously being treated with glucocorticoids, hormone replacement

therapy, thyroid/parathyroid medication, psychotropic medication,

anticonvulsants, selective estrogen receptor modulators or calcium

were excluded. Patients with the following conditions were also

excluded: Gastrectomy, inflammatory bowel disease, malignant

disease (gastric, esophageal, colon, lung, pancreatic, liver, bile

duct, gallbladder, breast, uterine, ovarian, prostate, and bladder

cancer, malignant lymphoma, leukemia and multiple myeloma), chronic

kidney disease, type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypo/hyper-thyroidism,

hypo/hyper-parathyroid disorder, rheumatoid arthritis (including

other collagen diseases), and those female patients who were

premenopausal.

Measurement of lumbar BMD

BMD at lumbar vertebrae 2 through 4 (L2-4) was

measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry using a Discovery

DXA® system (Hologic; Bedford, MA, USA) and the presence

of fragility fractures were investigated in the chest and lumbar

spine using lateral vertebral X-rays. The diagnosis of osteoporosis

was performed in accordance with the 2000 version of the Japanese

Diagnostic Criteria of the Japanese Society for Bone and Mineral

Research (11). Degenerative lesions

of the vertebrae were ruled out on diagnosing osteoporosis. An

osteoporotic patient was defined as one having lumbar BMD values

<70% of the young adult mean (YAM) in those without any

prevalent fragility fracture. Osteoporosis was also defined as the

presence of fragility fractures of any bone in a person with a BMD

of <80% of the YAM. Percentage change of lumbar BMD was

evaluated from baseline to the end of one year of treatment in the

AC and AD groups.

Measurement of bone turnover

markers

Serum bone-specific alkaline-phosphatase (BAP; a

biomarker of bone formation) and serum collagen type I cross-linked

N-telopeptide (NTX; a biomarker of bone resorption) were examined.

Percentage changes of NTX and BAP from baseline to the end of one

year of treatment were investigated in the AC and AD groups.

Upper GI findings and frequency scale

for the symptoms of GERD (FSSG)

The prevalence rate of upper GI endoscopy findings

were analyzed, including reflux esophagitis (RE), hiatal hernia

(HH) and peptic ulcer disease (PUD). RE was defined as grade A, B,

C, or D according to the Los Angeles Classification (12), and PUD as a gastric and/or duodenal

ulcer or ulcer scar. HH was defined as an apparent separation of

the esophagogastric junction and diaphragm impression by >2 cm

at endoscopy. The FSSG score was established via questionnaire

(13). Changes in the FSSG score from

the baseline to the end of one year of treatment, and findings of

upper GI endoscopy (RE, HH and PUD) at baseline and the end of one

year of treatment were evaluated.

Endpoint

In addition, the safety of use of the two

therapeutic agents over time was evaluated by assessing the side

effects experienced by patients in each group.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics were compared between

the AC and AD groups by paired t-test or Fisher's exact test. The

percentage change from baseline to the end of one year of treatment

for lumbar BMD, NTX, and BAP was investigated by paired t-test. The

change of FSSG score from baseline to the end of one year of

treatment in each group was also investigated by paired t-test and

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of the 22 patients enrolled in the present study,

six were excluded from evaluation [three patients in the AC group

(one was excluded due to medication side effects, one due to other

disease, and one dropped out of the study) and three patients in

the AD group (one due to medication side effects and two dropped

out of the study)].

The baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table I. Of the 16 eligible patients,

eight received AC treatment and eight received AD treatment. In the

AC and AD groups, respectively, 1 case vs. 3 cases received

rabeprazole; 5 cases vs. 1 case received omeprazole; and 2 cases

vs. 4 cases received lansoprazole. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences

in baseline characteristics between the two treatment groups. There

were no patients with fractures at the beginning of the study.

| Table I.Patient baseline characteristics. |

Table I.

Patient baseline characteristics.

| Patient profile | Total (n=16) | Alfacalcidol

(n=8) | Alendronate

(n=8) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years |

64.1±9.0 |

64.9±10.1 |

63.3±8.4 | 0.730 |

| Gender, n (%) |

|

|

| 1.000 |

| Male | 4

(25.0) | 2 (25.0) | 2

(25.0) |

|

|

Female | 12 (75.0) | 6 (75.0) | 6

(75.0) |

|

| Body mass index

(kg/m2) |

20.8±3.8 |

19.6±3.0 |

21.9±4.3 | 0.230 |

| Alcohol consumption,

n (%) |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

Non-drinker | 15 (93.8) | 7 (87.5) |

8 (100.0) |

|

|

Drinker | 1 (6.2) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| Smoking, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.569 |

|

Non-smoker | 12 (75.0) | 7 (87.5) | 5

(62.5) |

|

|

Smoker | 4 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) | 3

(37.5) |

|

| Comorbidities |

|

|

|

|

|

Diabetes mellitus, n (%) |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

No | 15 (93.8) | 7 (87.5) |

8 (100.0) |

|

|

Yes | 1 (6.2) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

Hypertension, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.569 |

|

No | 12 (75.0) | 7 (87.5) | 5

(62.5) |

|

|

Yes | 4 (25.0) | 1 (12.5) | 3

(37.5) |

|

| Concomitant

medications |

|

|

|

|

| Calcium

channel blocker, n (%) |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

Non-user | 13 (81.3) | 7 (87.5) | 6

(75.0) |

|

|

User | 3 (18.7) | 1 (12.5) | 2

(25.0) |

|

| Low

dose aspirin, n (%) |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

Non-user | 10 (62.3) | 5 (62.5) | 5

(62.5) |

|

|

User | 6 (37.6) | 3 (37.5) | 3

(37.5) |

|

|

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme

A reductase inhib-itors, n (%) |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

Non-user | 11 (68.8) | 6 (75.0) | 5

(62.5) |

|

|

User | 5 (31.2) | 2 (25.0) | 3

(37.5) |

|

| Bone turnover

marker |

|

|

|

|

|

Bone-specific alkaline

phos-phatase, U/l |

25.4±7.8 |

27.4±8.4 |

23.5±7.1 | 0.338 |

|

Collagen type I

cross-linked |

14.0±6.0 |

12.4±1.9 |

15.6±8.3 | 0.302 |

| N

telopeptide, nnmol BCE/l |

|

|

|

|

| Lumber dual-energy

X-ray absorptiometry |

|

|

|

|

| Bone

mineral density, g/cm2 |

0.66±0.12 |

0.62±0.14 |

0.70±0.10 | 0.182 |

| Upper

gastrointestinal findings |

|

|

|

|

| Reflux

esophagitis, n (%) |

|

|

| 1.000 |

|

No |

16 (100.0) |

8 (100.0) |

8 (100.0) |

|

|

Yes | 0

(0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| Hiatal

hernia, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.608 |

|

No | 10 (62.3) | 4 (50.0) | 6

(75.0) |

|

|

Yes | 6

(37.6) | 4 (50.0) | 2

(25.0) |

|

| Peptic

ulcer disease, n (%) |

|

|

| 0.569 |

|

No | 12 (75.0) | 5 (62.5) | 7

(87.5) |

|

|

Yes | 4

(25.0) | 3 (37.5) | 1

(12.5) |

|

| Questionnaire |

|

|

|

|

|

Frequency scale for the

symptoms of gastroesopha-geal reflux disease score |

6.5±6.1 |

3.6±3.0 |

9.4±7.2 | 0.056 |

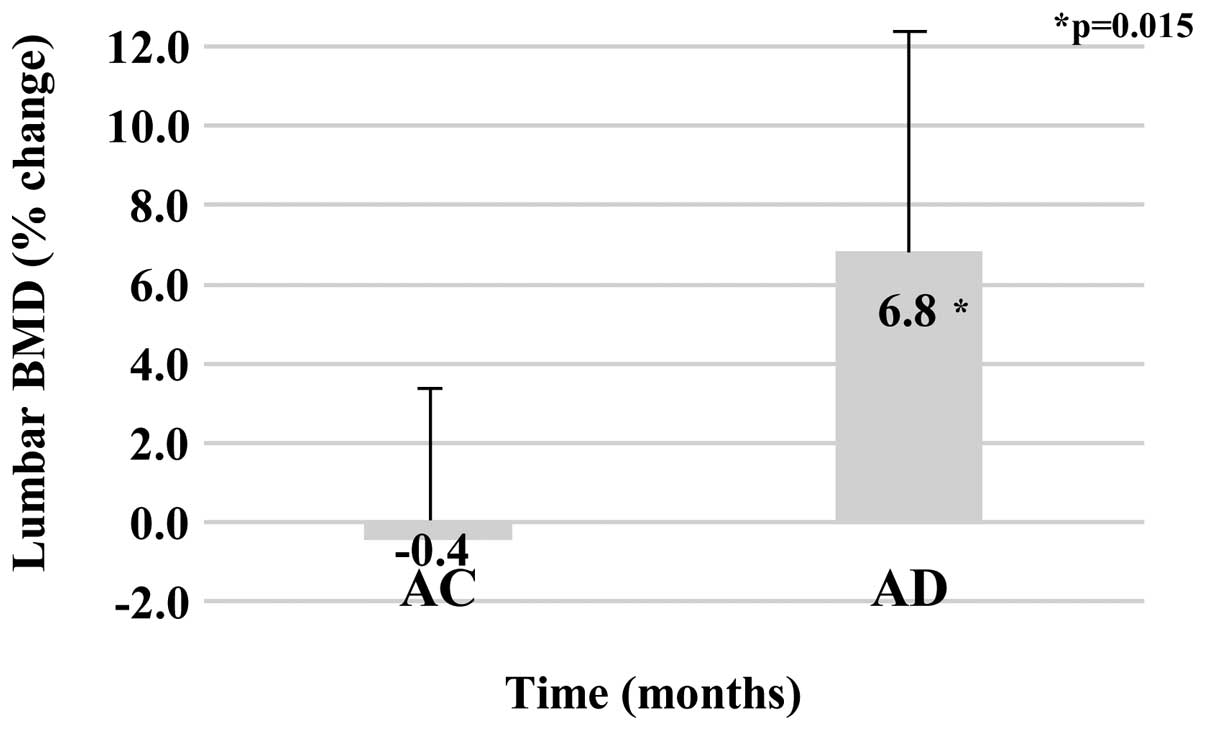

Lumbar BMD

Baseline values of lumbar BMD were 0.62±0.14

g/cm2 for the AC group and 0.70±010 g/cm2 for

the AD group (P=0.182). Following one year of treatment, the lumbar

BMD values were 0.61±0.12 g/cm2 for the AC group and

0.75±010 g/cm2 for the AD group. The percentage changes

in lumbar BMD from baseline to the end of one year of therapy were

−0.4±4.0% for the AC group and 6.8±6.3% for the AD group, with

significantly effective lumbar BMD findings identified in the AD

group (P=0.015; Fig. 1).

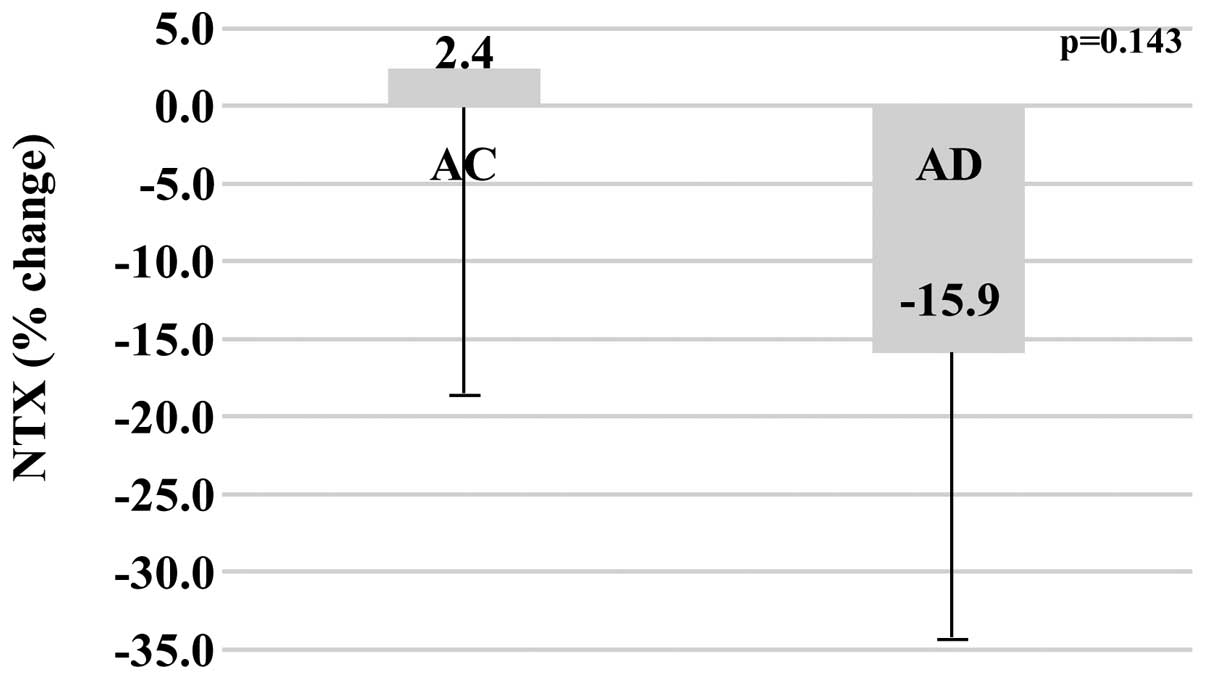

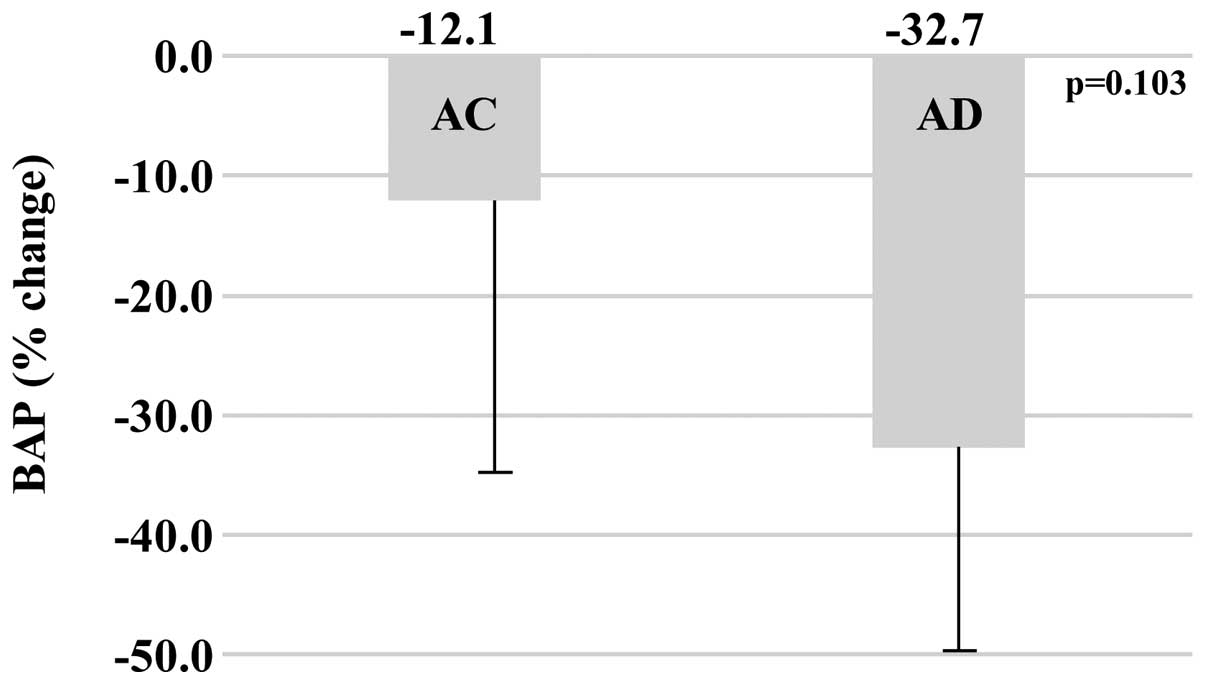

Bone turnover markers

The baseline values of bone turnover markers in the

AC and AD groups, respectively were as follows: BAP (U/l), 27.4±8.4

vs. 23.5±7.1 (P=0.338); NTX (nmol BCE/l), 12.4±1.9 vs. 15.6±8.3

(P=0.302). After one year of treatment, the values of bone turnover

markers in the AC and AD groups, respectively were as follows: BAP

(U/l), 23.6±7.3 vs. 15.1±4.1; NTX (nmol BCE/l), 12.8±4.5 vs.

12.6±8.7. When comparing the percentage change between baseline and

the end of one year of treatment, the AC group demonstrated less of

a change over time in BAP (−12.1±25.5%) compared with the AD group

(−32.7±21.7%) (P=0.103), and less of a change over time in NTX

(+2.4±25.7%) compared with the AD group (−15.9±21.3%) (P=0.143);

although the difference was not statistically significant (Figs. 2 and 3).

Upper GI findings

Baseline findings of the upper GI endoscopy

(Table I) indicated no RE in either

treatment group, HH in 50.0% of the AC group vs. 25.0% of the AD

group (P=0.608), PUD in 37.5% of the AC group vs. 12.5% of the AD

group (P=0.569). No novel findings of RE or PUD were observed from

baseline to the end of one year of treatment in either group.

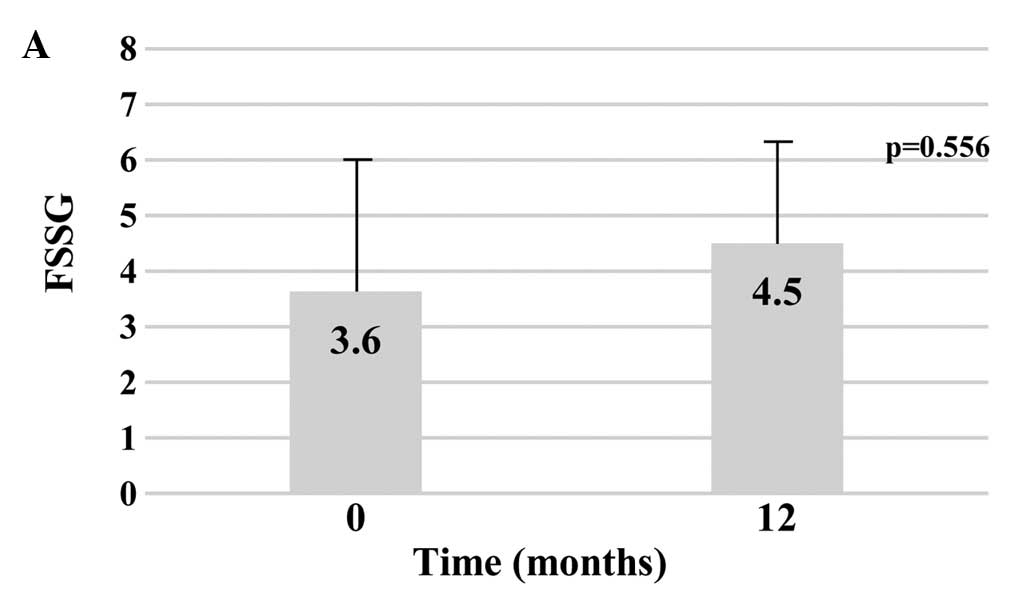

FSSG score

The mean baseline values for FSSG were 3.6±3.0 for

the AC group vs. 9.4±7.2 for the AD group (P=0.056). After one year

of treatment, the mean FSSG values were 4.5±2.8 for the AC group

and 8.3±5.1 for the AD group. The change from baseline FSSG scores

to the end of one year of treatment was not significantly different

in either group (AC group, P=0.556; AD group, P=0.723),

respectively (Fig. 4).

Safety analysis

Of the 22 patients that participated in this study,

six patients were excluded as mentioned above. In each group, the

side effect was mild nausea and the frequency of side effects was

the same between the two study groups (one case in each group). New

bone fractures were not observed from baseline to the end of one

year of treatment in either group.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

prospective, randomized, open-label study to investigate the

therapeutic efficacy of AC and AD, as estimated by lumbar BMD

changes in osteoporotic patients using concomitant PPIs. Although a

recent prospective study comparing AD and AC indicated that AD was

more efficacious than AC in increasing lumber BMD (14), the current study of osteoporotic

patients using PPIs demonstrated that lumbar BMD change following a

one-year treatment with AD was greater than that observed with AC

treatment. Furthermore, a previous report indicated that PPI use

was associated with a dose-dependent loss of AD anti-fracture

efficacy (10). According to certain

Japanese prospective studies, the lumbar BMD increase at one year

after AD treatment was ~6% (14,15) and in

the current study, the lumbar BMD increase after one year of AD

treatment in osteoporotic patients using PPIs (6.8%) was similar to

a previous study. However, a limitation of the present study was

that the number of study subjects was small; thus, further large

prospective studies are required to determine the effect of AD in

osteoporotic patients using concomitant PPIs.

It is hypothesized that PPIs attenuate the

therapeutic effect of bisphosphonate as follows: PPIs may decrease

the absorption of calcium; the dissolution of calcium carbonate is

a pH-dependent process and gastric pH is particularly important for

calcium absorption (16). As PPIs

strongly suppress gastric acid secretion, the dissolution of

calcium carbonate is inhibited by gastric juice with a high pH and,

as a result, calcium absorption may decrease. Similarly, an

association between PPI use and bone fracture is suggested in

western countries (17); however,

certain studies did not report any association between PPI use and

bone fracture (18) and there are few

prospective studies regarding the association between PPI use and

bone fracture.

It was reported that the occurrence of GI adverse

events was an independent determinant of persistence with

bisphosphonate therapy (19) and

adherence to bisphosphonate treatment may decrease due to GI

adverse events. However adherence to the bisphosphonate treatment

schedule was good in the present study (data not shown).

It was reported that PPIs suppress bone resorption

adversely by inhibiting the vacuolar proton pump of the osteoclast

(20). However, it was reported that

the concentrations of PPIs required for the inhibition of the

osteoclast proton pump are markedly higher than the tolerable

physiological concentrations (21).

Gertz et al (22) reported that

increasing gastric pH by infusion of ranitidine was associated with

a doubling of AD bioavailability. Recently, Itoh et al

(23) reported that risedronate

administration in combination with a PPI may be more effective for

treating osteoporosis and for improving physical fitness than

treatment with risedronate alone, although they evaluated the BMD

of the trabecular bone using quantitative computer tomography

(23).

According to previous reports, the lumbar BMD

increase following one year of AC treatment was ~1% (24,25), while

the current study indicated a lumbar BMD change of −0.4% after one

year of AC treatment. It was previously reported that

bisphosphonates reduce ~50% of bone turnover markers (15); however, no significant difference in

bone turnover markers was identified in the present study. A

limitation of the current investigation was that the number of

study subjects was small; therefore, the effect of AD on bone

turnover markers may not have been apparent.

It was suggested that osteoporotic patients

exhibiting lumbar pressure fractures or kyphosis are at risk of

GERD (26,27). Miyakoshi et al (28) also reported that increases in the angle

of lumbar kyphosis and the number of lumbar vertebral fractures may

represent very important risk factors for GERD in osteoporotic

patients. However, there are few reports about the association

between GERD symptoms using FSSG and bisphosphonates. In the

current study, the FSSG score did not change after the one-year

treatment with AD; therefore, the increase in GERD symptoms

triggered by long-term use was not observed.

Since there were no significant changes in frequency

or severity of side effects in the two treatment groups in this

study, concomitant PPI use with AD may present as a safe

therapeutic strategy. Furthermore, no increased findings of RE or

PUD were observed over the one year of treatment with either AD or

AC. As the residence time in the esophagus of the medication was

considered a mechanism of the risk for esophagitis (4), the patients in the current study were

instructed comprehensively about the appropriate dosing regimen

(taking a tablet with enough water and remaining upright for ≥30

min before the first food of the day).

There were certain limitations of the current study.

The study was not a double-blind trial, but an open-labeled study.

The number of study subjects was particularly small; therefore, a

large prospective multicenter trial is required. Furthermore,

patients used different PPIs, which may have influenced certain

results, such as lumbar BMD and the FSSG score. Family histories of

osteoporosis or certain other important risk factors, such as

exercise, sunlight exposure, dietary calcium intake, or the use of

over-the-counter medication and other nutrients were not

investigated.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated via

lumbar BMD change that a one-year treatment with AD was more

efficacious than with AC in osteoporotic patients using PPIs.

Furthermore, as with previous reports, the percentage change in

lumbar BMD following one year of AD treatment was similar (6.8%) in

osteoporotic patients using PPIs. However, additional, large

prospective multicenter trials are required to further clarify the

efficacy of bisphosphonate administration with PPIs in osteoporosis

treatment.

References

|

1

|

Iki M: Epidemiology of osteoporosis in

Japan. Clin Calcium. 22:797–803. 2012.(In Japanese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Liberman UA, Weiss SR, Bröll J, Minne HW,

Quan H, Bell NH, Rodriguez-Portales J, Downs RW Jr, Dequeker J,

Favus M, et al: The Alendronate Phase III Osteoporosis Treatment

Study Group: Effect of oral alendronate on bone mineral density and

the incidence of fractures in postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J

Med. 333:1437–1443. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

de Groen PC, Lubbe DF, Hirsch LJ, Daifotis

A, Stephenson W, Freedholm D, Pryor-Tillotson S, Seleznick MJ,

Pinkas H and Wang KK: Esophagitis associated with the use of

alendronate. N Engl J Med. 335:1016–1021. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Graham DY, Malaty HM and Goodgame R:

Primary amino-bisphosphonates: A new class of gastrotoxic drugs -

comparison of alendronate and aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol.

92:1322–1325. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Yoshimura N, Muraki S, Oka H, Kawaguchi H,

Nakamura K and Akune T: Cohort profile: Research on

osteoarthritis/osteoporosis against disability study. Int J

Epidemiol. 39:988–995. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Nagasue T, Nakamura S, Kochi S, Kurahara

K, Yaita H, Kawasaki K and Fuchigami T: Time trends of the impact

of Helicobacter pylori infection and nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs on peptic ulcer bleeding in Japanese

patients. Digestion. 91:37–41. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kinoshita Y, Kawanami C, Kishi K, Nakata

H, Seino Y and Chiba T: Helicobacter pylori independent

chronological change in gastric acid secretion in the Japanese.

Gut. 41:452–458. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Fujiwara Y and Arakawa T: Epidemiology and

clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J

Gastroenterol. 44:518–534. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Malfertheiner P, Fass R, Quigley EM,

Modlin IM, Malagelada JR, Moss SF, Holtmann G, Goh KL, Katelaris P,

Stanghellini V, et al: Review article: From gastrin to

gastro-oesophageal reflux disease - a century of acid suppression.

Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 23:683–690. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Abrahamsen B, Eiken P and Eastell R:

Proton pump inhibitor use and the antifracture efficacy of

alendronate. Arch Intern Med. 171:998–1004. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Orimo H, Hayashi Y, Fukunaga M, Sone T,

Fujiwara S, Shiraki M, Kushida K, Miyamoto S, Soen S, Nishimura J,

et al: Osteoporosis Diagnostic Criteria Review Committee: Japanese

Society for Bone and Mineral Research: Diagnostic criteria for

primary osteoporosis: Year 2000 revision. J Bone Miner Metab.

19:331–337. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL,

Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler

SJ, et al: Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: Clinical and

functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles

classification. Gut. 45:172–180. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Sugimoto S,

Kawamura O, Maeda M, Minashi K, Kuribayashi S, Higuchi T, Zai H,

Ino K, et al: Development and evaluation of FSSG: Frequency scale

for the symptoms of GERD. J Gastroenterol. 39:888–891. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Shiraki M, Kushida K, Fukunaga M,

Kishimoto H, Taga M, Nakamura T, Kaneda K, Minaguchi H, Inoue T,

Morii H, et al: The Alendronate Phase III Osteoporosis Treatment

Research Group: A double-masked multicenter comparative study

between alendronate and alfacalcidol in Japanese patients with

osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 10:183–192. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Uchida S, Taniguchi T, Shimizu T, Kakikawa

T, Okuyama K, Okaniwa M, Arizono H, Nagata K, Santora AC, Shiraki

M, et al: Therapeutic effects of alendronate 35 mg once weekly and

5 mg once daily in Japanese patients with osteoporosis: A

double-blind, randomized study. J Bone Miner Metab. 23:382–388.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Sipponen P and Härkönen M: Hypochlorhydric

stomach: A risk condition for calcium malabsorption and

osteoporosis? Scand J Gastroenterol. 45:133–138. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S and Metz DC:

Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture.

JAMA. 296:2947–2953. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kaye JA and Jick H: Proton pump inhibitor

use and risk of hip fractures in patients without major risk

factors. Pharmacotherapy. 28:951–959. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Penning-van Beest FJ, Goettsch WG, Erkens

JA and Herings RM: Determinants of persistence with

bisphosphonates: A study in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Clin Ther. 28:236–242. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tuukkanen J and Väänänen HK: Omeprazole, a

specific inhibitor of H+-K+-ATPase, inhibits bone resorption in

vitro. Calcif Tissue Int. 38:123–125. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Mattsson JP, Väänänen K, Wallmark B and

Lorentzon P: Omeprazole and bafilomycin, two proton pump

inhibitors: Differentiation of their effects on gastric, kidney and

bone H(+)-translocating ATPases. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1065:261–268. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gertz BJ, Holland SD, Kline WF,

Matuszewski BK, Freeman A, Quan H, Lasseter KC, Mucklow JC and

Porras AG: Studies of the oral bioavailability of alendronate. Clin

Pharmacol Ther. 58:288–298. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Itoh S, Sekino Y, Shinomiya K and Takeda

S: The effects of risedronate administered in combination with a

proton pump inhibitor for the treatment of osteoporosis. J Bone

Miner Metab. 31:206–211. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Orimo H, Shiraki M, Hayashi Y, Hoshino T,

Onaya T, Miyazaki S, Kurosawa H, Nakamura T and Ogawa N: Effects of

1 alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3 on lumbar bone mineral density and

vertebral fractures in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Calcif Tissue Int. 54:370–376. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Shikari M, Kushida K, Yamazaki K, Nagai T,

Inoue T and Orimo H: Effects of 2 years' treatment of osteoporosis

with 1 alpha-hydroxy vitamin D3 on bone mineral density and

incidence of fracture: A placebo-controlled, double-blind

prospective study. Endocr J. 43:211–220. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Yoshimura M, Nagahara A, Ohtaka K, Shimada

Y, Asaoka D, Kurosawa A, Osada T, Kawabe M, Hojo M, Yoshizawa T, et

al: Presence of vertebral fractures is highly associated with

hiatal hernia and reflux esophagitis in Japanese elderly people.

Intern Med. 47:1451–1455. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Yamaguchi T, Sugimoto T, Yamada H, Kanzawa

M, Yano S, Yamauchi M and Chihara K: The presence and severity of

vertebral fractures is associated with the presence of esophageal

hiatal hernia in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 13:331–336.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Miyakoshi N, Kasukawa Y, Sasaki H, Kamo K

and Shimada Y: Impact of spinal kyphosis on gastroesophageal reflux

disease symptoms in patients with osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int.

20:1193–1198. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|