Introduction

Mesenteric panniculitis (MP) is a rare idiopathic

condition characterised histologically by chronic inflammatory and

fibrosis of mesenteric adipose tissue (1-2). Ogden

et al (3) introduced the

term MP to encompass sclerosing mesenteritis and mesenteric

lipodystrophy. While these conditions share the same features, they

differ in the relative predominance of chronic inflammation or

fibrosis Pathological features predominant in inflammation are

termed MP, whereas those predominant in fibrosis are termed

sclerosing mesenteritis (1-2). A systematic review showed that MP

primarily affects middle-aged men, presenting most commonly with

abdominal pain (78.1%), followed by fever (26.0%), weight loss

(22.9%), diarrhoea (19.3%) and vomiting (18.2%) (1). Abdominal tenderness (38.0%) and masses

(34.4%) are observed on physical examination (1). MP diagnosis is difficult due to the

presentation of non-specific symptoms and unclear findings. Chylous

ascites has been reported in two case series of patients with MP,

demonstrating frequencies of 18.5% (minimal chylous ascites)

(3) and 14.1% (no information

regarding amount of ascites) (4).

To the best of our knowledge, few case reports describe massive

chylous ascites (5-7).

Similarly, chylous pleural effusion, a rare complication in

patients with MP, has only been documented in two reports, to the

best of our knowledge (8-9).

Protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) is characterised by

uncompensated loss of plasma protein in the intestines, leading to

panhypoproteinemia in the absence of liver or kidney dysfunction

(10,11). Studies have identified mucosal

damage and lymph drainage failure as primary mechanisms underlying

PLE, with several factors contributing to the development of these

mechanisms, including inflammatory conditions (such as Crohn's

disease and ulcerative colitis), cardiovascular disorders (such as

chronic congestive heart failure) and widespread abdominal

malignant neoplasms (such as malignant lymphoma and multiple

myeloma) (10-11). To the best of our knowledge,

however, only six cases of MP-associated PLE have been published

(12-17).

The present study reported a case of MP complicated

by massive chylous ascites, pleural effusion and PLE and reviewed

clinicopathological characteristics of these conditions.

Case report

Case presentation

A 56-year-old male presented to Osaka Medical and

Pharmaceutical University Hospital (Osaka, Japan, in May 2023 for

dyspnoea. The patient had no history of diabetes mellitus,

allergies, malignancy or thoracic/abdominal surgery, but showed a

significant smoking history of 10 cigarettes/day for 34 years. The

patient initially noted the development of systemic oedema,

transient abdominal pain and fever and weight loss (approximately

20 kg) in June 2018; consultation revealed hypoalbuminemia (1.6

g/dl, reference range: 4.1-5.1). The patient was subsequently

referred to Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University Hospital,

Osaka, Japan, in November 2018. Physical examination revealed

massive ascites, which was confirmed to be chylous on abdominal

paracentesis. Endoscopy of the small intestine and duodenum

revealed mucosal oedema. Histopathological specimens were fixed in

10% formalin at room temperature for 24 h, dehydrated in ethanol

and xylene at room temperature, and embedded in paraffin (60˚C).

The 4-micrometer sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin

for 5 min each at room temperature. Histopathological study using

light microscope of duodenal mucosa showed lymphangiectasia of the

lamina propria (magnification, x400). Therefore, the patient was

diagnosed with PLE with massive chylous ascites. Prednisolone (20

mg/day for 3 years, per oral), albumin preparation (Albuminar 25%,

twice, per intravenous injection), and diuretic agents

(Spironolactone, 100 mg/day for 3 years, per oral)were

administered, resulting in the improvement of oedema. During the 3

years following initial presentation, the patient reported gradual

and uncontrolled fluid accumulation. A peritovenous shunt for

peritoneal fluid drainage into the internal jugular vein was placed

in December 2020, which stabilised symptoms.

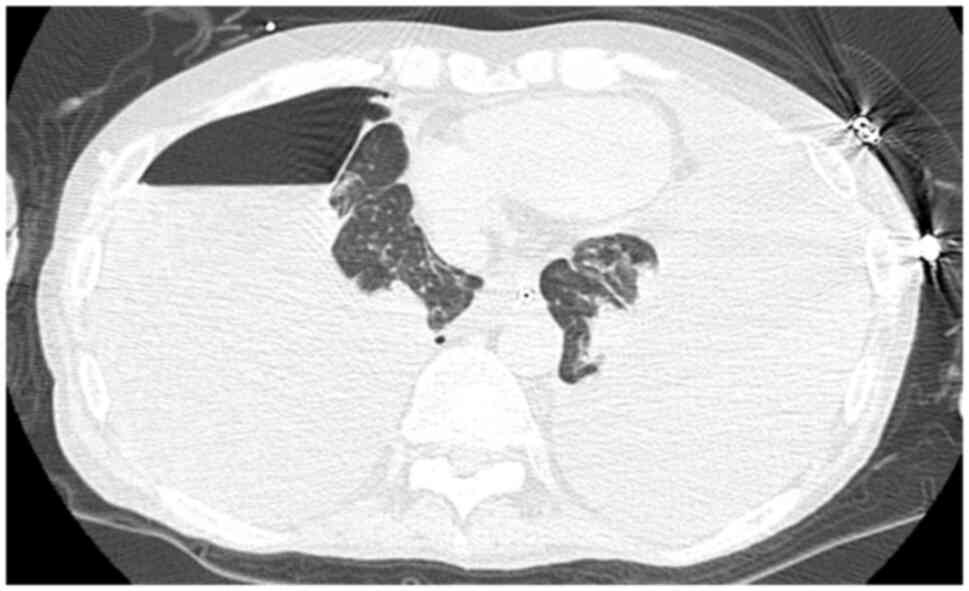

Computed tomography (CT) (Aquilion-ONE, Canon

Medical Systems, Japan) without contrast agent revealed

pneumothorax of the right lung, massive bilateral pleural effusion

and shrunken bilateral lungs (Fig.

1) in March 2023. Drainage of the right thoracic cavity was

attempted but the right lung failed to expand. Elevated levels of

white blood cells (13.63x103/µl; range:

3.3-8.6x103) and C-reactive protein (13.63 mg/dl, range:

<0.14), along with ground-glass opacity on CT, indicated

pulmonary infection, prompting the initiation of various antibiotic

regimens [Voriconazole (300 mg x 2/day), Ampicillin/Sulbactam (3 g

x 4/day), and Vancomycin (1,000 mg x 2/day) per intravenous

injection for three weeks (all)]. However, due to elevated liver

enzyme levels [aspartate aminotransferase, 1,467 U/l (reference

range 13-30) and alanine aminotransferase 829 U/l (reference range

10-42)], antibiotics were discontinued in April 2023. Respiratory

failure worsened due to increasing pleural effusion and persistent

lung collapse, leading to death in April 2023.

Autopsy findings

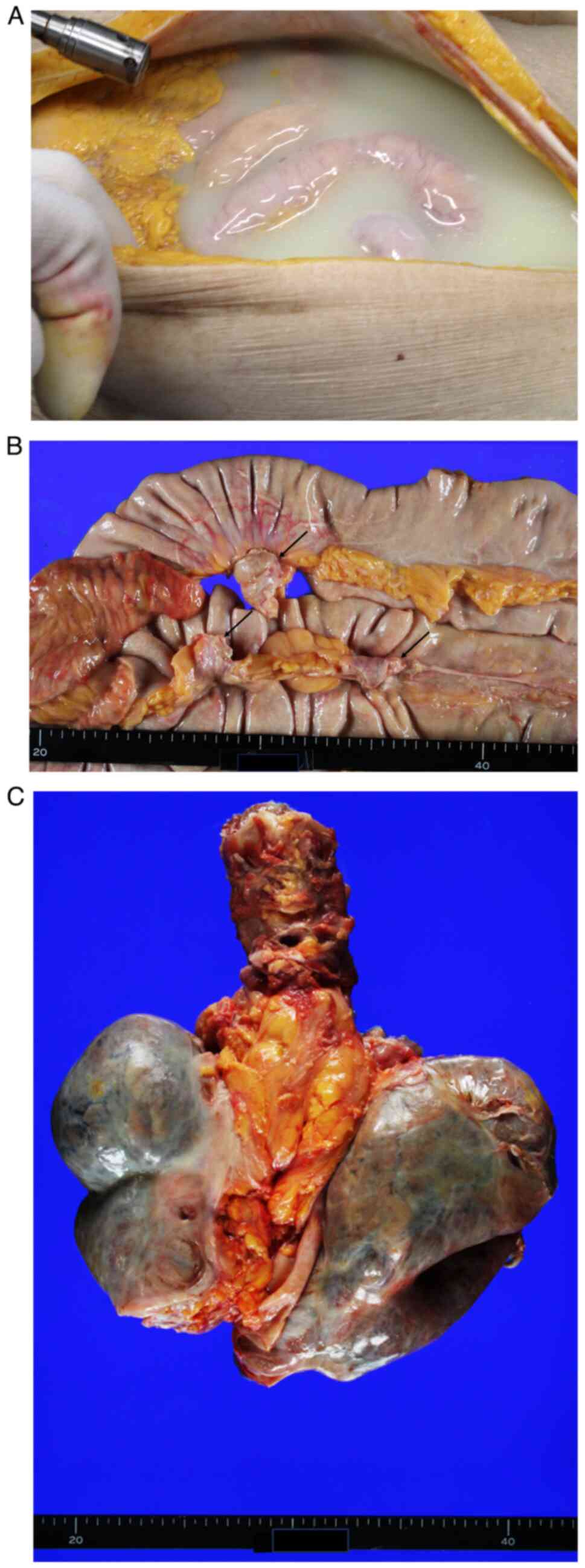

Upon opening the abdominal wall, massive chylous

ascites (3680 ml) was observed (Fig.

2A). Massive chylous pleural effusion in bilateral pleural

cavities (left, 1,650; right, 2,160 ml) was also present. The

mesentery of the small intestine was thickened, hardened and

appeared slightly whitish in colour (Fig. 2B). Similar thickening was observed

in the mesocolon. Calcified nodules, measuring 2-3 cm in diameter,

were present in the small bowel mesentery (Fig. 2B), with a few identified in the

mesocolon. Bilateral lungs were shrunken and their surfaces were

covered with dense, white fibrous tissue (Fig. 2C). Examination of the diaphragm

revealed no visible defects.

Histopathological and

immunohistochemical findings

Autopsy specimens were fixed in 10% formalin at room

temperature for 48 h, dehydrated in ethanol and xylene at room

temperature and embedded in paraffin (60˚C). The 4-micrometer

tissue sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin for 5 min

each at room temperature. Immunohistochemical analyses were

performed using an autostainer (Leica Bond-III; Leica Biosystem

GmbH). The 4-micrometer tissue sections were incubated with mouse

monoclonal antibody against IgG4 (clone HP6025, cat. no. 605-900;

1:400 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) and mouse monoclonal

antibody against podoplanin (clone D2-40, cat. No. M361901-2,

pre-diluted, Agilent Technologies Inc.) for 20 min at room

temperature. Secondary antibodies were pre-diluted and were used to

incubate the sections for 8 min at room temperature (Novolink Max

Polymer Detection System (cat. No. RE7140-L; Leica Biosystems

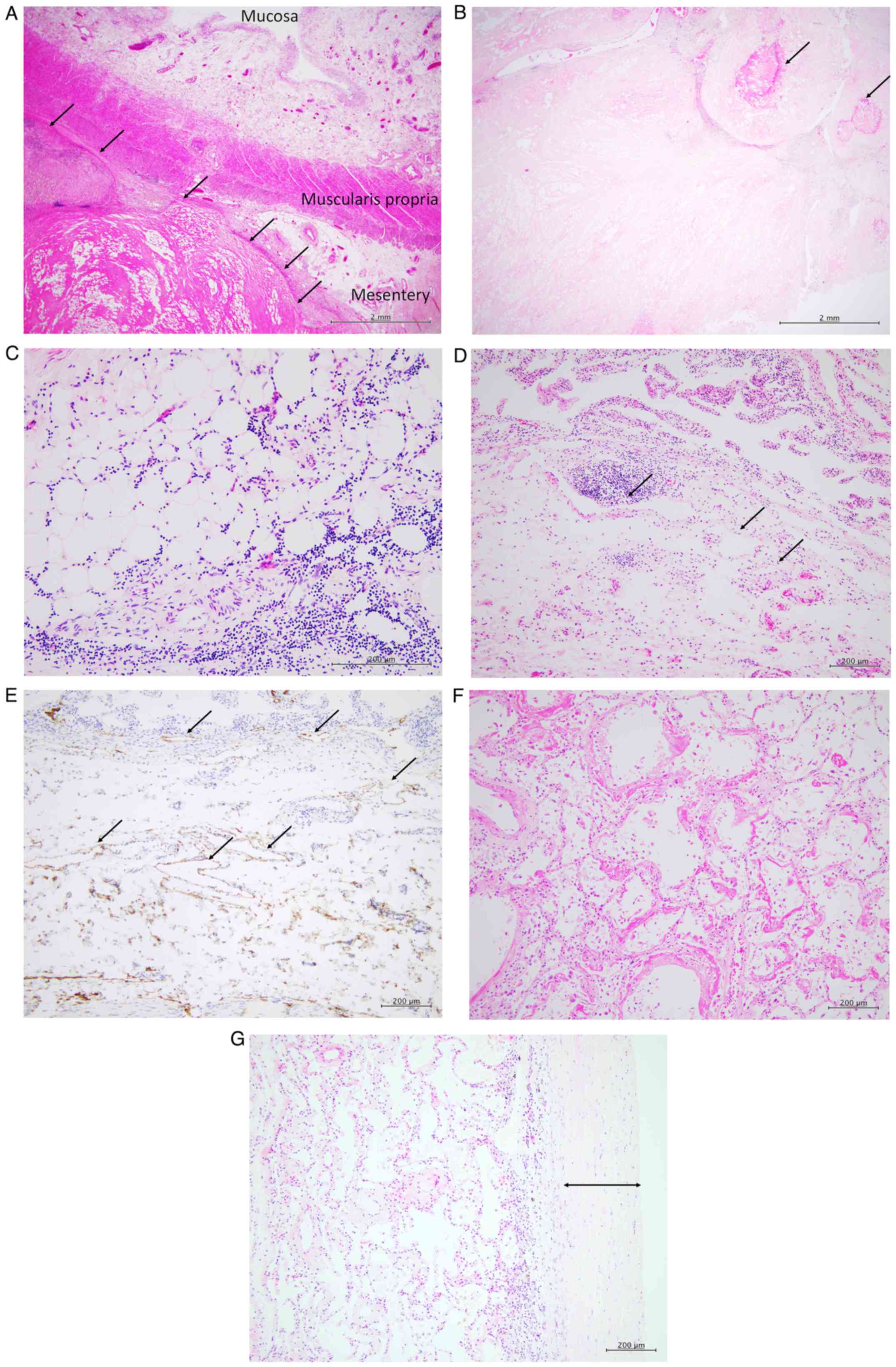

GmbH). Microscopic examination showed diffuse fat necrosis and

fibrosclerosis in the mesentery of the small intestine (Fig. 3A), with calcification within the

necrotic and fibrotic areas (Fig.

3B). Small lymphocytic infiltration without plasma cells was

observed within the mesenteric adipose tissue surrounding necrotic

areas (Fig. 3C).

Immunohistochemical staining showed no IgG4-positive plasma cells.

Collectively, these features supported the diagnosis of MP.

Examination of small intestine confirmed

lymphangiectasia in the lamina propria of the mucosa and submucosa

(Fig. 3D). This was confirmed by

positive podoplanin immunostaining, a marker for lymphatic

endothelial cells (18) (Fig. 3E).

Microscopic examination of bilateral lungs showed

diffuse alveolar damage, characterised by hyaline membrane

formation (Fig. 3F). Diffuse

fibrosclerotic thickening of the visceral pleura was observed,

corresponding to the gross findings of shrunken lungs covered with

dense, white fibrous tissue (Fig.

3G).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first to report MP accompanied by massive chylous ascites,

pleural effusion and PLE. Although a premortem diagnosis of MP was

not made, histopathological examination during autopsy revealed

findings that were consistent with MP. Excessive fluid buildup and

protein loss were likely attributed to intestinal lymph drainage

obstruction caused by mesenteric inflammation, fibrosis and fat

necrosis in MP.

MP is an idiopathic condition characterised by

chronic inflammation and fibrosis of mesenteric adipose tissue

(1-2). MP is associated with infection,

autoimmune disease and abdominal trauma (1). Certain cases of MP result from

IgG4-associated diseases (19).

although most cases showed no such associations (20). Therefore, the absence of

IgG4-positive plasma cells in the present cased ruled out

differential diagnoses for IgG4-related diseases. Since MP is

predominant in middle-aged male patients presenting with

non-specific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, fever, weight loss

and diarrhoea (1), its diagnosis is

often difficult. Previous studies have reported a postmortem

diagnosis of MP, similar to the present case (9,14).

Imaging studies may be valuable diagnostic tools in visualizing

certain MP features. CT demonstrates hyperattenuating fat with

tumoural pseudocapsules and soft tissue nodules in the mesentery

(1,4,21).

Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrates an ill-defined,

hyperintense signal in mesenteric fat on T2-weighted imaging,

reflecting early-stage oedema, followed by a hypointense signal in

later stages (1). Calcification,

which is a potential consequence of fat necrosis, may be observed

in the mesentery (4,7,14), as

in the present case. Notably, the presence of calcification might

be a characteristic finding on CT scans for MP. Furthermore, while

small intestinal mesentery is the most commonly affected site

(1), lesions in both the small

intestine and colon are possible, as in the present case. The

treatment strategy for MP typically involves administration of

steroids, colchicine, tamoxifen and antibiotics, with over 70% of

patients showing symptom resolution (1,4,21).

However, non-responders have been documented (1,4,14,15),

with some developing fatal outcomes on follow-up (1,9,14).

Here, the patient succumbed to respiratory failure despite medical

treatment.

Massive chylous pleural effusion and PLE were rare

features in the present case. Table

I summarises clinicopathological characteristics of MP cases

with chylous pleural effusion or PLE, including the present case

(8,9,12-17).

To the best of our knowledge, only two prior cases of MP with

massive pleural effusion have been documented (8,9).

Kobayashi et al (9) reported

an autopsy-confirmed case of MP with relatively minimal chylous

ascites (200 ml) and massive pleural effusion (left, 1,300; right,

1,400 ml). Although the mechanism underlying chylous effusion in

bilateral thoracic cavities remains unclear, transfer from the

abdomen via a diaphragmatic defect is hypothesized (8,9).

Similarly, bilateral pleural effusion may be present in patients

with hepatic hydrothorax and diaphragmatic defect (22,23).

In the present case, massive chylous ascites and pleural effusion

were observed. While no macroscopic diaphragmatic defect was

observed during autopsy, negative intrathoracic pressure may have

facilitated transfer of chylous fluid from the abdomen to the

pleural cavity. Additionally, autopsy revealed shrunken lungs

covered with dense, white fibrous tissue. This feature resembles

‘trapped lung’, which is a consequence of dysfunctional healing

following pleural injury (24).

This condition progresses from lung entrapment to formation of a

visceral pleural peel, persistent pleural effusion and inability of

the lung to expand (24). These

changes are marked by fibrosis and scarring of visceral pleura,

resulting in a peel-like appearance and trapped lung (24). While infection is the most common

cause, pneumothorax, haemothorax, thoracic intervention and

rheumatoid pleuritis can also lead to trapped lungs (24). Moreover, Owen et al (25) reported complications of trapped

lungs and chylothorax in a patient with long-standing cirrhosis due

to hepatitis C. Considering the aforementioned findings, the

persistent massive chylous pleural effusion in the present case may

have contributed to the development of trapped lungs.

| Table IClinicopathological features of

mesenteric panniculitis with chylous pleural effusion and/or

protein-losing enteropathy. |

Table I

Clinicopathological features of

mesenteric panniculitis with chylous pleural effusion and/or

protein-losing enteropathy.

| Patient no. | Age | Sex | Symptoms | Ascites | Pleural effusion | Protein-losing

enteropathy | Treatment | Outcome | First author,

year | (Refs.) |

|---|

| 1 | 81 | Male | Dyspnea, fatigue,

abdominal pain, diarrhea | Yes | Yes | No | Pleurodesis | Lost to

follow-up | Rice et al,

2010 | (8) |

| 2 | 81 | Female | Edema, fatigue,

dyspnea | Yes | Yes | No | Azosemide (60

mg/day), heparin (10,000 IU/day) | Died of respiratory

failure | Kobayashi et

al, 2018 | (9) |

| 3 | 54 | Male | Diarrhea | No | No | Yes | Prednisolone | Improved | Höring | (12) |

| 4 | 68 | Male | Hypoalbuminemia,

edema | Yes | No | Yes | Prednisolone 60

mg/day for six weeks and tapered to10 mg/day), Colchicine (0.6

mg/day), Azathioprine (from 100 mg/day to 200 mg/day),

Cyclophosphamide and thalidomide (no detailed information were

available) | No improvement of

serum albumin | Rajendran and

Duerksen. 2006 | (13) |

| 5 | 77 | Male | Abdominal distention,

diarrhea | Yes | No | Yes | Albumin

preparation | Died | Kida et al.

2011 | (14) |

| 6 | 28 | Male | Abdominal pain | No | No | Yes | Prednisolone (30

mg/day) Colchicine and Azathioprine | No improvement of

symptom | Endo et al.

2014 | (15) |

| 7 | 59 | Male | Abdominal pain,

vomiting, diarrhea | No | No | Yes | Prednisolone (60

mg/day) and tamoxifen (20 mg/day) | Died of ischemic

ileo-colitis | Rispo et al,

2015 | (16) |

| 8 | 75 | Male | Abdominal

distention | Yes | No | Yes | Prednisolone (40

mg/day) | No improvement | Saito et al.

2017 | (17) |

| Present | 56 | Male | Edema, dyspnea | Yes | Yes | Yes | Prednisolone (20

mg/day per oral), Albumin preparation (Albuminar 25%, twice,

perintravenous injection),and Spironolactone (100 mg/day for 3

years, per oral), Voriconazole (300 mg x 2/day per intravenous

injection for 3 weeks), Ampicillin/Sulbactam (3 g x 4/day, per

intravenous injection for 3 weeks), and Vancomycin (1,000 mg x

2/day, per intravenous injection for 3 weeks) | Died of respiratory

failure | Nakazawa et

al, 2024 | - |

Despite its rare occurrence, PLE can be a symptom of

MP (Table I). Chylous ascites have

been noted in four of seven patients with MP and PLE including the

present patient (13,14,17).

Among MP patients with PLE, only one showed symptom improvement

with steroid therapy (12). In the

present case, the patient initially showed improvement of oedema,

although worsening ascites and pleural effusion were observed. The

occurrence of PLE in MP is likely due to lymphangiectasia of the

small intestinal mucosa caused by lymph drainage obstruction

(14). Autopsy findings in the

present case suggested MP as the underlying cause of PLE. Although

rare, PLE may be recognised as a possible complication of MP.

Examination including imaging studies and histological examination

of the affected mesentery are therefore warranted for diagnosis of

MP.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first to describe MP with massive ascites, pleural effusion and

PLE, highlighting the potential of MP changes in obstructing lymph

drainage in the mesentery. Despite its rarity and non-specific

symptoms, MP should be included as a differential diagnosis in

patients presenting with the aforementioned features.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms Shizuka Ono, Mr

Yusuke Ohnishi and Mr Naoto Kohno (all Department of Pathology,

Osaka Medical and Pharmaceutical University, Osaka, Japan) for

technical assistance.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

MI conceived and designed the study. YN, MI, KS, FS,

TS and YH interpreted clinical findings. YN, MI, KS, FS, TS and YH

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. YN and MI wrote the

manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The patient's family provided written informed

consent for participation.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was

obtained from the patient's family.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Sharma P, Yadav S, Needham CM and

Feuerstadt P: Sclerosing mesenteritis: A systematic review of 192

cases. Clin J Gastroenterol. 10:103–111. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Emory TS, Monihan JM, Carr NJ and Sobin

LH: Sclerosing mesenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis and mesenteric

lipodystrophy: A single entity? Am J Surg Pathol. 21:392–398.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ogden WW II, Bradburn DM and Rives JD:

Mesenteric panniculitis: Review of 27 cases. Ann Surg. 161:864–875.

1965.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA and Smyrk

TC: Sclerosing mesenteritis: Clinical features, treatment, and

outcome in ninety-two patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

5:589–596. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Arora M and Dubin E: A clinical case

study: Sclerosing mesenteritis presenting as chylous ascites.

Medscape J Med. 10(30)2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ehrenpreis ED, Boiskin I and Schaefer K:

Chylous ascites in a patient with mesenteric panniculits. J Clin

Gastroenterol. 42:327–328. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Lim HW and Sultan KS: Sclerosing

mesenteritis causing chylous ascites and small bowel perforation.

Am J Case Rep. 18:696–699. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Rice BL, Stoller JK and Heresi GA:

Transudative chylothorax associated with sclerosing mesenteritis.

Respir Care. 55:475–477. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kobayashi H, Notohara K, Otsuka T,

Kobayashi Y, Ujita M, Yoshioka Y, Suzuki N, Aoyagi R, Ohashi R and

Suzuki T: An autopsy case of mesenteric panniculitis with massive

pleural effusions. Am J Case Rep. 19:13–20. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Ozen A and Lenardo MJ: Protein-losing

enteropathy. N Engl J Med. 389:733–748. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Strober and Fuss IJ: Protein-losing

enteropathies. In: Mestecky J, Strober W, Russell MW, eds. Mucosal

Immunology. 4th ed. Academic Press, Boston, 1667-1694, 2015.

|

|

12

|

Höring E, Hingerl T, Hens K, von Gaisberg

U and Kieninger G: Protein-losing enteropathy: First manifestation

of sclerosing mesenteritis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 7:481–483.

1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Rajendran B and Duerksen DR: Retractile

mesenteritis presenting as protein-losing gastroenteropathy. Can J

Gastroenterol. 20:787–789. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kida T, Suzuki K, Matsuyama T, Okita M,

Isozaki Y, Matsumoto N, Miki S, Nagao Y, Kawabata K, Kohno M and

Oyamada H: Sclerosing mesenteritis presenting as protein-losing

enteropathy: A fatal case. Intern Med. 50:2845–2849.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Endo K, Moroi R, Sugimura M, Fujishima F,

Naitoh T, Tanaka N, Shiga H, Kakuta Y, Takahashi S, Kinouchi Y and

Shimosegawa T: Refractory sclerosing mesenteritis involving the

small intestinal mesentery: A case report and literature review.

Intern Med. 53:1419–1427. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Rispo A, Sica M, Bucci L, Musto D, Camera

L, Ciancia G, Luglio G and Caporaso N: Protein-losing enteropathy

in sclerosing mesenteritis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 19:477–480.

2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Saito Y, Hiramatsu K, Nosaka T, Ozaki Y,

Takahashi K, Naito T, Ofuji K, Matsuda H, Ohtani M, Nemoto T, et

al: A case of protein-losing enteropathy caused by sclerosing

mesenteritis diagnosed with capsule endoscopy and double-balloon

endoscopy. Clin J Gastroenterol. 10:351–356. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ordóñez NG: Podoplanin: A novel diagnostic

immunohistochemical marker. Adv Anat Pathol. 13:83–88.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Liu Z, Jiao Y, He L, Wang H and Wang D: A

rare case report of immunoglobulin G4-related sclerosing

mesenteritis and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore).

99(e22579)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Avincsal MO, Otani K, Kanzawa M, Fujikura

K, Jimbo N, Morinaga Y, Hirose T, Itoh T and Zen Y: Sclerosing

mesenteritis: A real manifestation or histological mimic of

IgG4-related disease? Pathol Int. 66:158–163. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wang H, Zhao Z, Cao Q and Ning J: A review

of 17 cases of mesenteric panniculitis in Zhengzhou ninth people's

hospital in China. BMC Gastroenterol. 24(48)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Cardenas A, Kelleher T and Chopra S:

Review article: Hepatic hydrothorax. Aliment Pharmacol Ther.

20:271–279. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Roussos A, Philippou N, Mantzaris GJ and

Gourgouliannis KI: Hepatic hydrothorax: Pathophysiology diagnosis

and management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 22:1388–1393.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Huggins JT, Sahn SA, Heidecker J, Ravenel

JG and Doelken P: Characteristics of trapped lung: Pleural fluid

analysis, manometry, and air-contrast chest CT. Chest. 131:206–213.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Owen SC, Bersabe DR, Skabelund AJ, McCann

ET and Morris MJ: Transudative chylothorax from cirrhosis

complicated by lung entrapment. Respir Med Case Rep.

28(100243)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|