Introduction

Reperfusion, the prompt restoration of the blood

supply to the ischemic tissue, is the most effective way to reduce

the process of ischemic injury, which ultimately leads to cell

death. However, reperfusion following even brief periods of

ischemia causes irreversible damage, known as ischemia-reperfusion

injury (1). Although the

mechanisms underlying ischemia-reperfusion injury are complicated,

oxidative stress is considered to play a pivotal role.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) was the third

gaseous signaling molecule to be discovered, following nitric oxide

and carbon monoxide (2).

H2S is produced endogenously from cysteine by the

pyridoxal-5′-phosphate-dependent enzymes, cystathionine β-synthase

(CBS) and/or cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE). Previously, a number of

studies have suggested that H2S has anti-inflammatory,

anti-oxidative and anti-apoptotic effects (3,4).

H2S inhibits lipid peroxidation during heart

ischemia-reperfusion and decreases the mortality of myocardial

cells induced by ischemia by reducing oxygen free radicals

(4). Also, in brain

ischemia-reperfusion injury, H2S exerts a protective

effect on neurons by eliminating oxygen free radicals (5). Studies have shown that H2S

has protective effects on the heart, brain, liver and lung in the

case of ischemia-reperfusion injury (6–9). In

the gastrointestinal tract, it has been reported that the systemic

administration of sodium hydrogen sulfide (NaHS), a H2S

donor, attenuates gastric mucosal injury by downregulating mRNA

expression and plasma release of proinflammatory cytokines in rats

(10). The protective effect of

exogenously administered H2S and its precursors NaHS and

L-cysteine (L-cys), has been shown against ischemia-reperfusion

injury. However, the potential of endogenous H2S has not

yet been investigated. The aim of this study was to investigate

whether endogenous H2S plays a role in gastric

ischemia-reperfusion (GI-R) injury.

We hypothesize that H2S plays an

important role in the gastric mucosa under ischemia-reperfusion.

Thus, we explored the effect of endogenous H2S on rat

GI-R injury by pretreatment with DL-propargylglycine (PAG) and

L-cys to block CSE and H2S synthetase and provide a

precursor of H2S synthesis. Furthermore, we determined

whether the effect of endogenous H2S is related to

oxidative enzymes involved in GI-R.

Materials and methods

Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 200–250 g

were provided by the Animal Department of Xuzhou Medical College.

All animal care and experimental protocols complied with the Animal

Management Rules of the Ministry of Health of the People’s Republic

of China and the guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals of Xuzhou Medical College.

Chemicals

L-cys and PAG were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St.

Louis, MO, USA). Malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione (GSH),

superoxide dismutase (SOD) and superoxide anion

(O2−) assay kits were purchased from Nanjing

Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China). Rabbit

polyclonal antibodies to SOD-1 (sc-11407) and xanthine oxidase

(XOD, sc-20991) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

(Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to CSE (BA2198)

were purchased from Wuhan Boster Biological Technology Co. Ltd.,

(Wuhan, China). Goat anti-rabbit IgG was purchased from Beijing

Zhong Shan-Golden Bridge Biological Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing,

China). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical

grade.

GI-R injury model

The rats were fasted without water deprivation for

24 h before the experiments. After inducing anesthesia with an

intraperitoneal injection of 10% chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg body

weight), the rats were fixed on an operating table. Following

laparotomy, the celiac artery was carefully separated from

surrounding tissues, clamped with an artery clamp to induce

ischemia and later removed to allow reperfusion (11). Following surgery, all rats were

sacrificed under anesthesia and the stomach was carefully excised

for determination of gastric mucosal damage or stored at −80°C for

MDA and GSH assays, and the measurement of XOD and SOD expression

by western blot analysis.

Measurement of H2S

concentration in gastric mucosa and serum

Following sacrifice, a blood sample was rapidly

collected from each rat and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 4 min.

Then the supernatant was used for H2S measurement using

a commercially-available kit (12). The mucosa of the stomach was

scraped off, homogenized and centrifuged and then the supernatant

was collected for the measurement of H2S

concentration.

Measurement of gastric mucosal

damage

The stomach was cut open along the greater gastric

curvature, rinsed and flattened. The general injury area of the

gastric mucosa was calculated using Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe

Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). The injury area was expressed as

the percentage of congestion, edema and erosion in the whole

gastric mucosa area. A 1-mm tissue sample was removed from between

the greater and lesser gastric curvatures and fixed in 10%

formaldehyde, then processed by routine paraffin embedding,

sectioning and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The degree

of pathological injury was assessed under a light microscope (each

sample was blindly evaluated by a pathologist). The degree of

injury was scored according to the Masuda criteria (13) with slight modification: normal, 0;

injury in surface epithelium, 1; congestion and edema in the upper

mucosa, 2; congestion, hemorrhage and edema in the middle and lower

mucosa, 3; structural disorder or necrosis in the upper mucosal

glands, 4 and deep necrosis and ulceration, 5. The average injury

score for each section was calculated. The mean of 10 visual scores

from each slide was calculated as the score for one rat.

Assay of MDA and GSH content, SOD

activity and the inhibition of O2−

production

The gastric mucosa was made into a 10% tissue

homogenate and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm, 4°C for 10 min; then the

supernatant was collected. Following the manufacturer’s

instructions, the MDA and GSH contents in the supernatant were

assessed by the thiobarbituric acid and

3,3′-dithiobis(6-nitrobenzoic) acid methods, respectively. The

protein content was determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA)

method. SOD activity in the supernatant was evaluated by the

inhibition of XOD, according to the manufacturer’s instructions and

expressed as units per milligram tissue (U/mg). Inhibition of

O2− production was measured according to the

manufacturer’s instructions and expressed as units per gram tissue

(U/g).

Western blot analysis of CSE, XOD and

SOD

Gastric mucosal protein was extracted according to

the BCA method. The concentration of each sample was diluted to the

same level, then mixed with 1/3 volume protein denaturation

solution and boiled for 5 min to denature the protein. Samples were

separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gels.

Membranes were probed with polyclonal antibodies to CSE, SOD and

XOD overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibody was conjugated to

horseradish peroxidase with a BCIP/NBT kit (Promega Corporation,

Madison, WI, USA). β-actin was used to normalize for loading

variations.

Experimental protocol

The rats were randomly divided into 4 groups with 10

per group: i) sham group, age-matched healthy rats were only

laparotomized without celiac artery clamping; ii) GI-R group,

age-matched healthy rats were intraperitoneally injected with

normal saline for 7 days, then the celiac arteries were clamped for

30 min ischemia and then reperfused for 60 min; iii) PAG group, the

rats were intraperitoneally injected with the H2S

synthetase blocker PAG (50 mg/kg/day) for 7 days, then the celiac

arteries were clamped for 30 min ischemia and then reperfused for

60 min and iv) L-cys group, the rats were intraperitoneally

injected with L-cys (50 mg/kg/day) for 7 consecutive days, then the

celiac arteries were clamped for 30 min ischemia and then

reperfused for 60 min.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation

(SD). Statistical analysis was performed by SPSS 13.0 (SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows. Statistical significance was

calculated by one-way analysis of variance. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

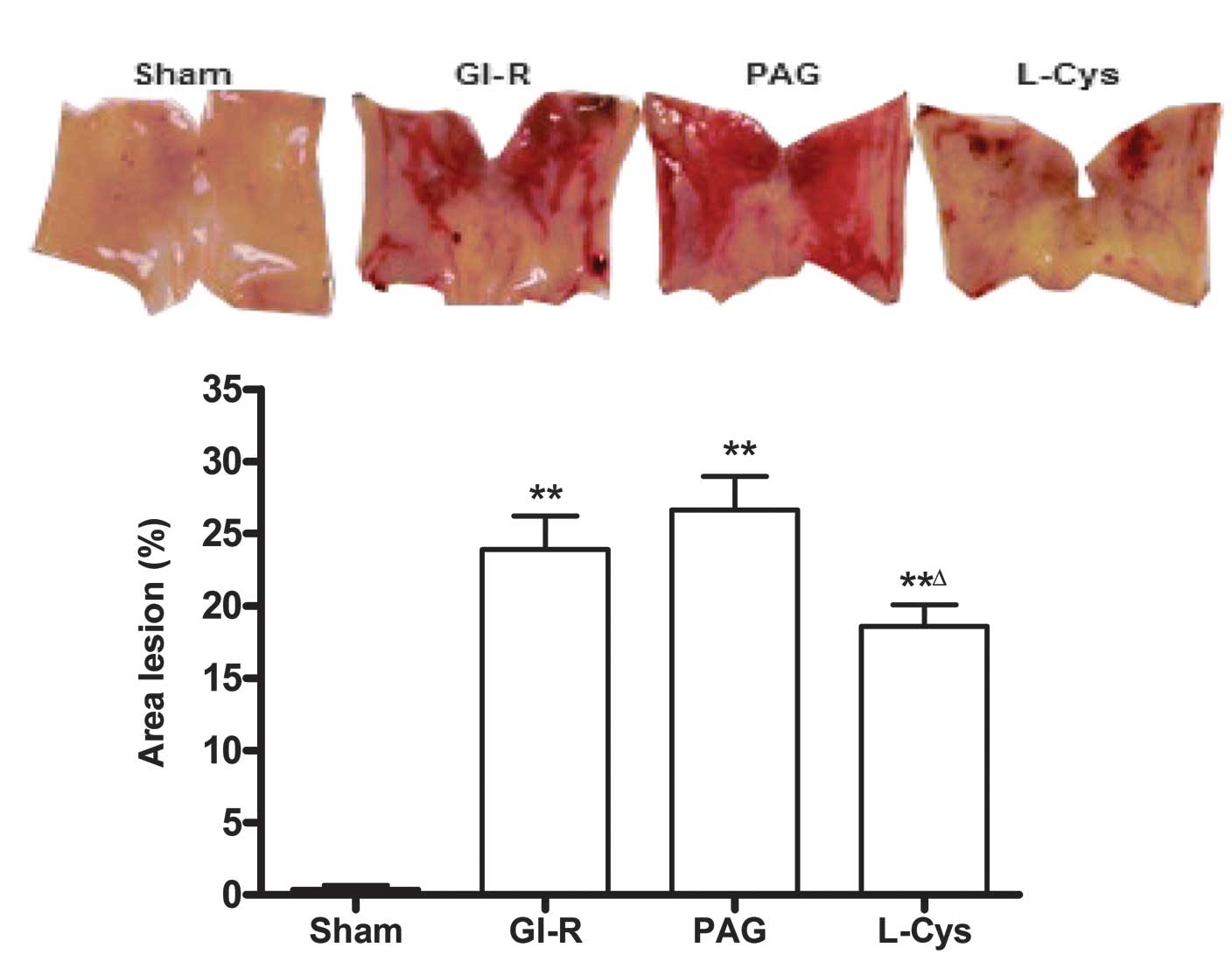

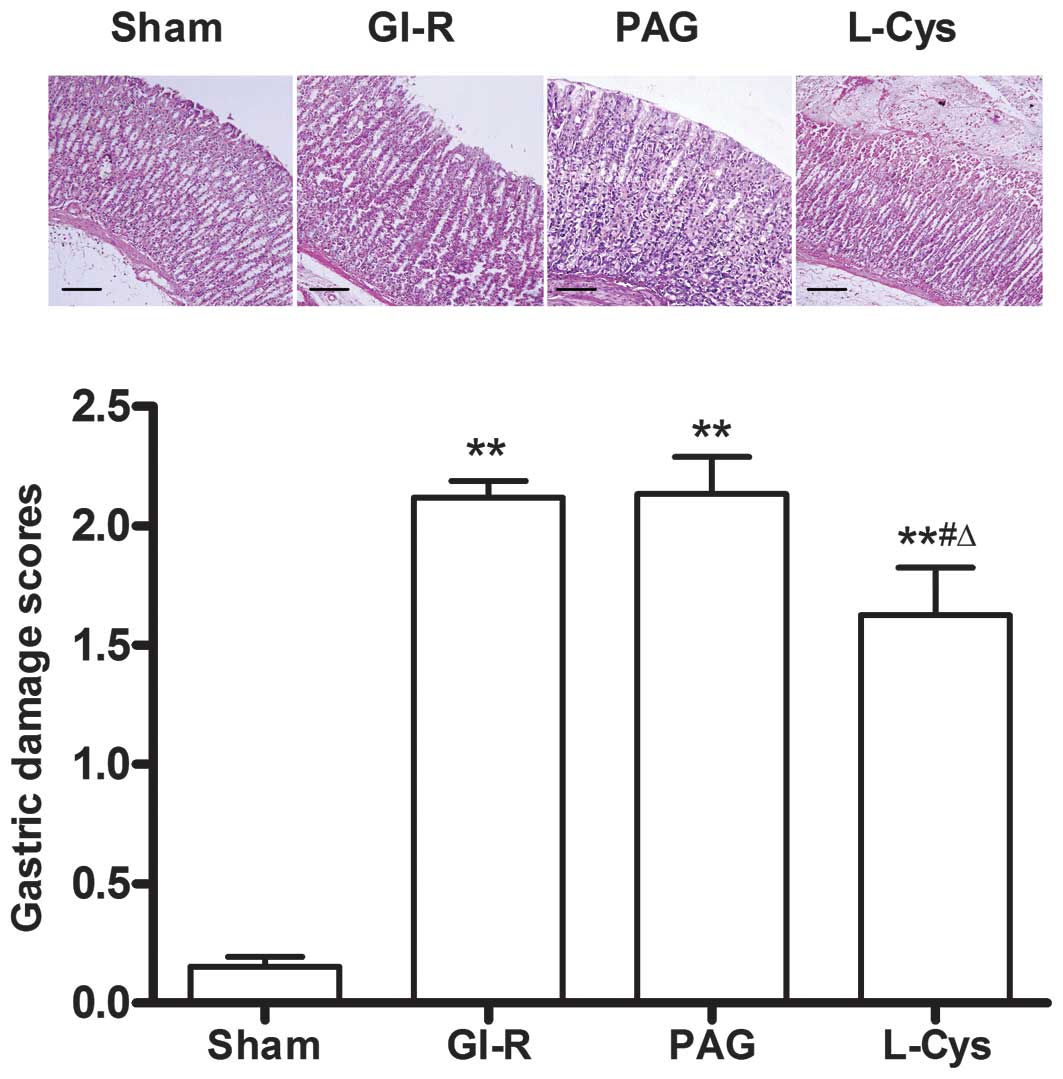

Gastric mucosal injury

The mucosal surface of the sham group was smooth and

no significant abnormality in the gastric mucosa was observed under

the light microscope. However, significant hemorrhage and edema and

several erosions of varying depths and sizes were observed on the

surface of the mucosa of the GI-R group. The epithelial cells and

gland ducts of the mucosa at the hemorrhage sites were shed and

disorganized in the GI-R group. Compared with the GI-R group, the

injury area and the extent of mucosal damage significantly

increased in the PAG group and L-cys inhibited the damage induced

by GI-R (P<0.05; Fig. 1). Under

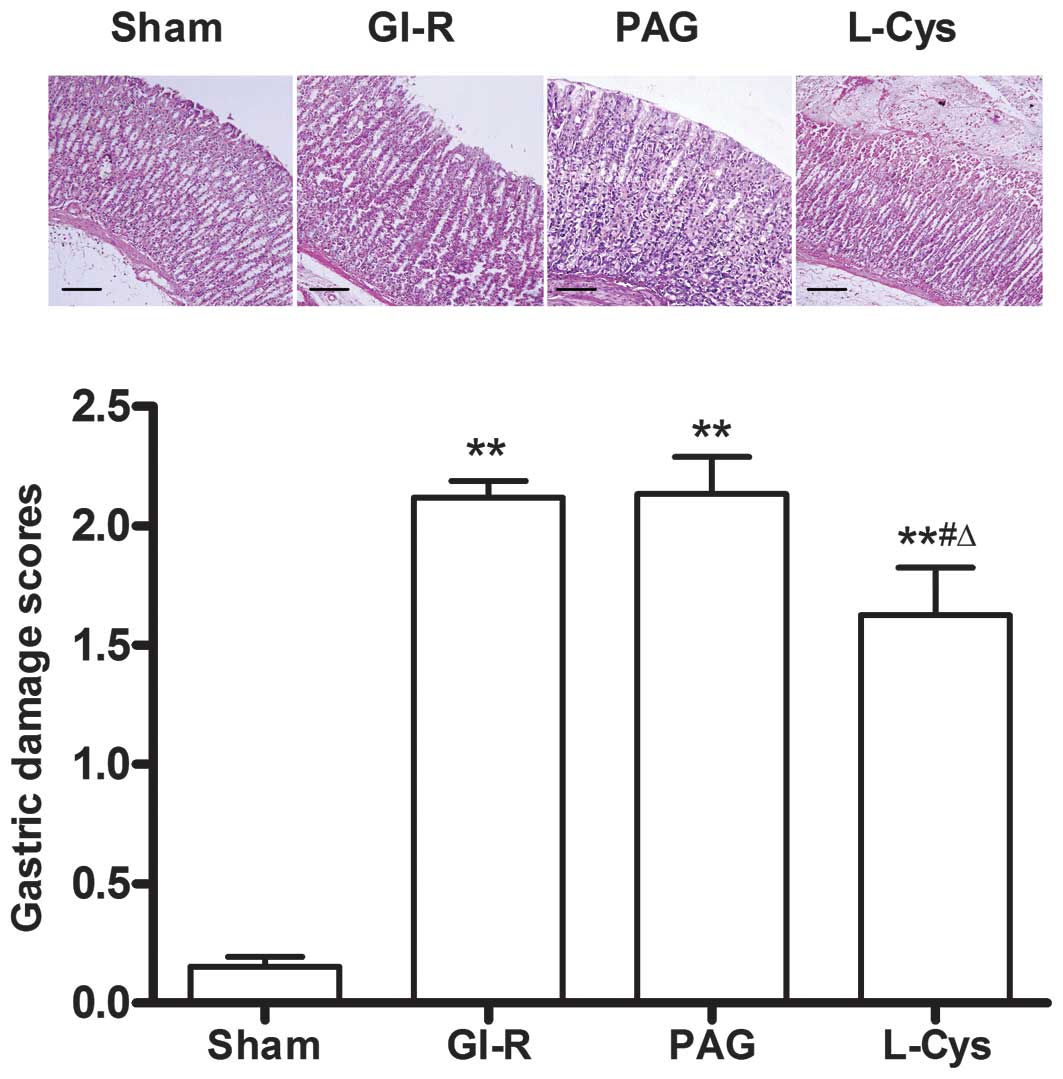

the light microscope, the gastric damage scores in the GI-R, PAG

and L-cys groups were much higher than those in the sham group

(P<0.01). However, the damage score in the L-cys group was lower

than those of the GI-R and PAG groups (P<0.05, Fig. 2).

| Figure 2.Effects of PAG and L-cys on gastric

mucosal injury scores in rats subjected to gastric

ischemia-reperfusion (GI-R) (hematoxylin and eosin stain;

magnification, ×100). Male Sprague-Dawley rats were

intraperitoneally injected with the H2S synthetase

blocker PAG (50 mg/kg) or L-cys (50 mg/kg) for 7 days before the

celiac arteries were clamped for 30 min ischemia and then

reperfused for 60 min. Sham group, age-matched rats with

physiological solute treatment but no GI-R procedure; GI-R group,

age-matched rats with physiological solute treatment followed by

the GI-R procedure; PAG group, rats intraperitoneally injected with

PAG and then subjected to the GI-R procedure; L-cys group, rats

intraperitoneally injected with L-cys and then subjected to the

GI-R procedure. Scale bar, 200 μm. Data presented as mean ±

standard deviation (SD), n=8. **P<0.01 vs. the sham

group, #P<0.05 vs. the GI-R group,

ΔP<0.05 vs. the PAG group. PAG, DL-propargylglycine;

L-cys, L-cysteine; H2S, hydrogen sulfide. |

H2S concentration in the serum

and gastric mucosal tissue

Although there were no significant changes in

H2S concentration in the serum (Fig. 3B), compared with the sham and GI-R

groups, PAG decreased the concentration of H2S in the

gastric mucosa (P<0.05) and L-cys attenuated this decrease

(P<0.05). However, there was no significant difference in

H2S level in the gastric mucosa between the GI-R and

sham groups (Fig. 3A).

| Figure 3.Effects of PAG and L-cys on

H2S concentration in the gastric mucosa (A) and serum

(B) from rats subjected to gastric ischemia-reperfusion (GI-R).

Male Sprague-Dawley rats were intraperitoneally injected with the

H2S synthetase blocker PAG (50 mg/kg) or L-cys (50

mg/kg) for 7 days before the celiac arteries were clamped for 30

min ischemia and then reperfused for 60 min. Sham group,

age-matched rats with physiological solute treatment but no GI-R

procedure; GI-R group, age-matched rats with physiological solute

treatment followed by the GI-R procedure; PAG group, rats

intraperitoneally injected with PAG and then subjected to the GI-R

procedure; L-cys group, rats intraperitoneally injected with L-cys

and then subjected to the GI-R procedure. Data presented as mean ±

standard deviation (SD), n=8. *P<0.05 vs. the sham

group, #P<0.05 vs. the GI-R group,

ΔP<0.05 vs. the PAG group. PAG, DL-propargylglycine;

L-cys, L-cysteine; H2S, hydrogen sulfide. |

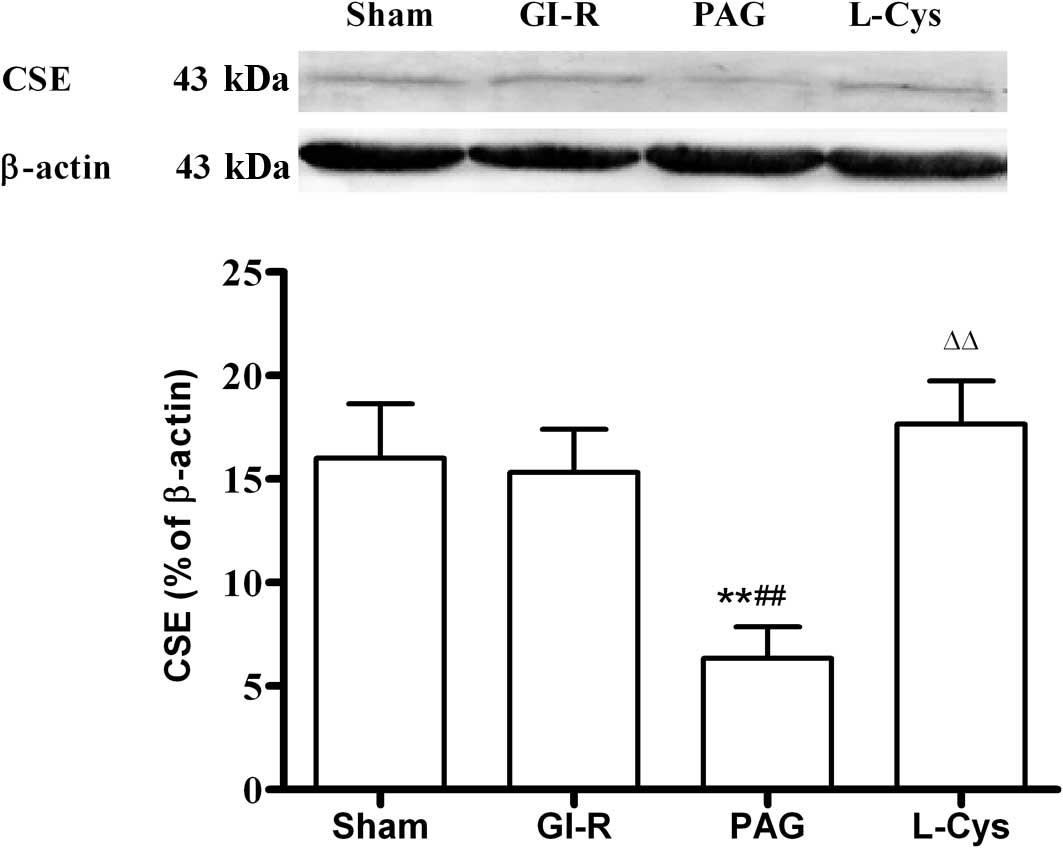

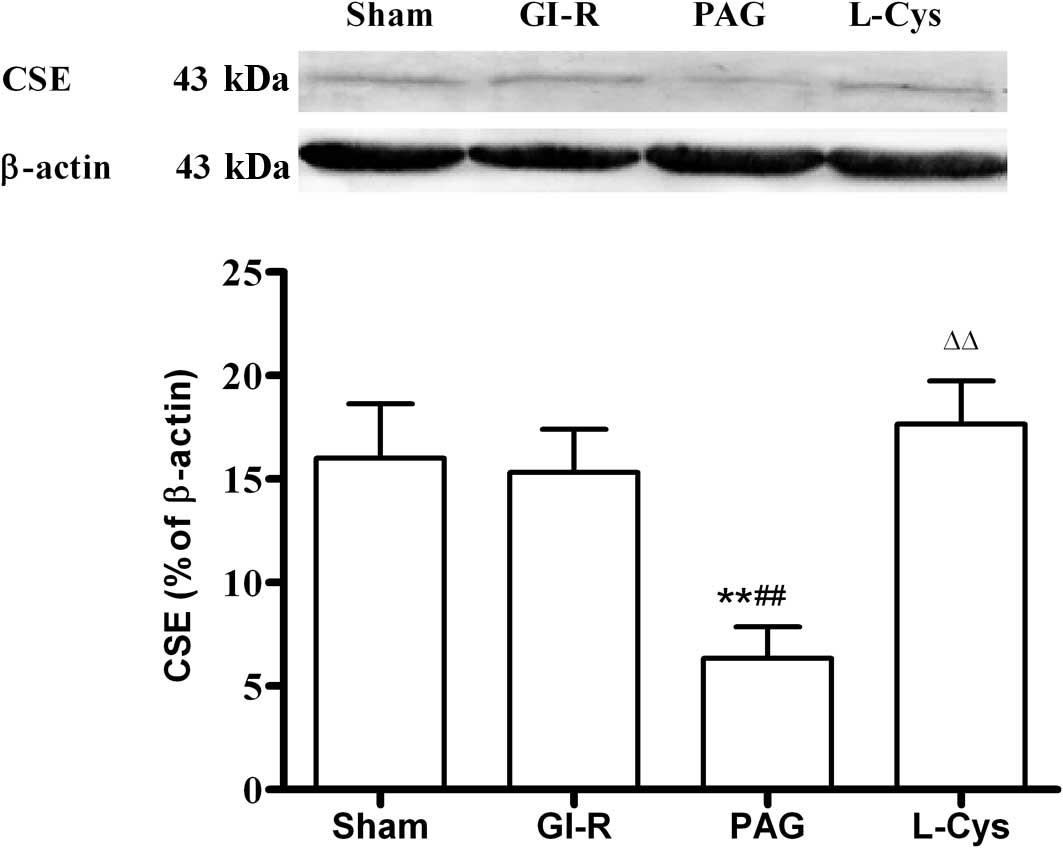

CSE expression in the gastric mucosa

Compared with the sham group, GI-R alone had no

effect on CSE expression. PAG significantly inhibited the

expression of CSE (P<0.01) and L-cys increased CSE in the

gastric mucosa to normal levels (P<0.01; Fig. 4).

| Figure 4.Effects of PAG and L-cys on CSE

expression in gastric mucosa from rats subjected to gastric

ischemia-reperfusion (GI-R). Male Sprague-Dawley rats were

intraperitoneally injected with the H2S synthetase

blocker PAG (50 mg/kg) or L-cys (50 mg/kg) for 7 days before the

celiac arteries were clamped for 30 min ischemia and then

reperfused for 60 min. Sham group, age-matched rats with

physiological solute treatment but no GI-R procedure; GI-R group,

age-matched rats with physiological solute treatment followed by

the GI-R procedure; PAG group, rats intraperitoneally injected with

PAG and then subjected to the GI-R procedure; L-cys group, rats

intraperitoneally injected with L-cys and then subjected to the

GI-R procedure. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD),

n=3. **P<0.01 vs. the sham group,

##P<0.01 vs. the GI-R group, ΔΔP<0.01

vs. the PAG group. PAG, DL-propargylglycine; L-cys, L-cysteine;

H2S, hydrogen sulfide; CSE, cystathionine γ-lyase. |

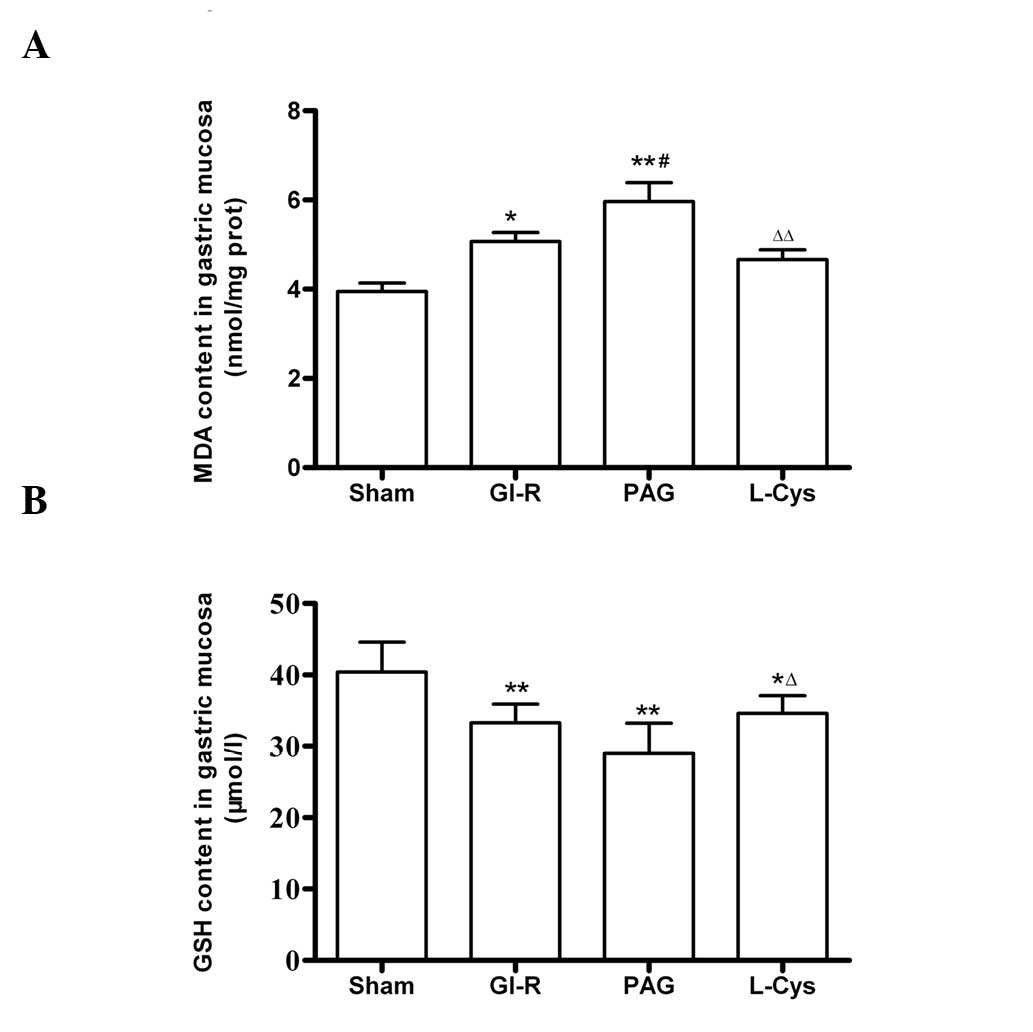

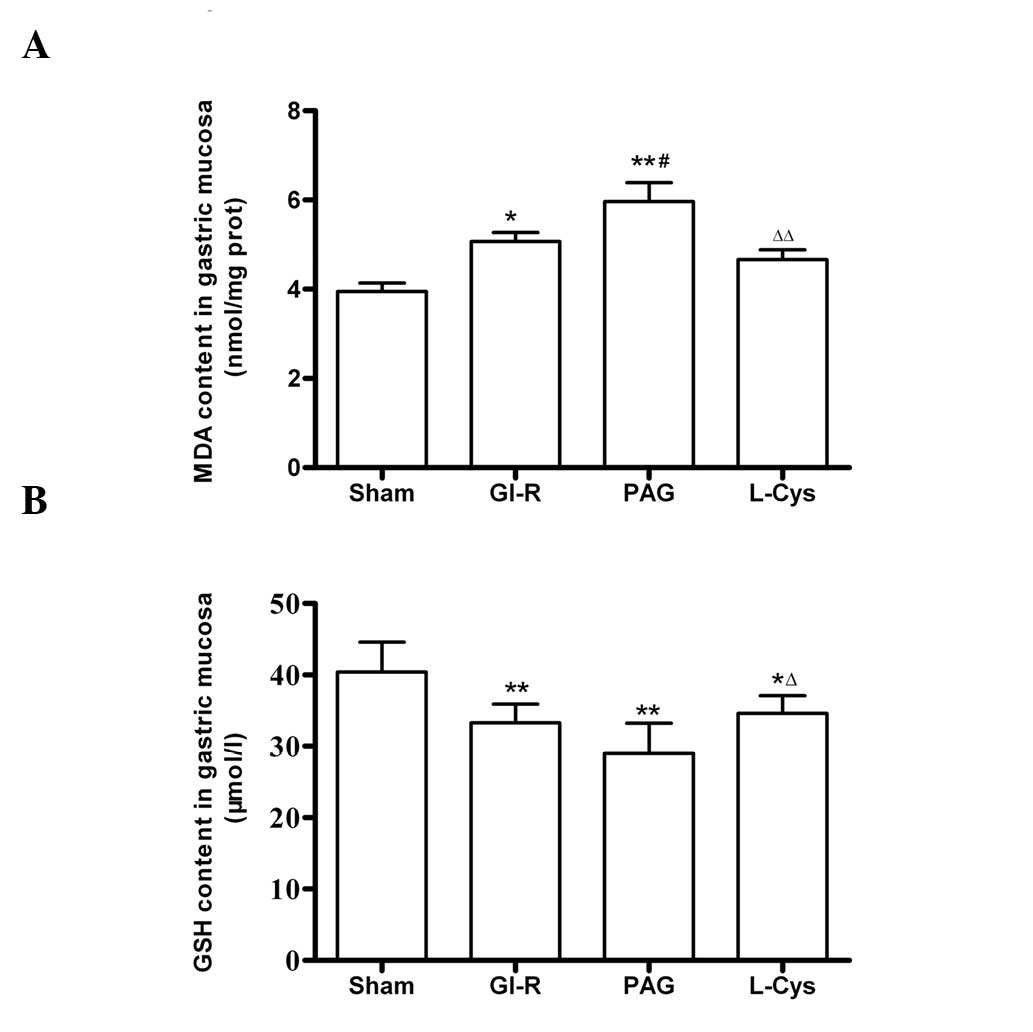

MDA and GSH contents in the gastric

mucosa

The MDA content of the mucosa increased following

GI-R (P<0.05) and further increased in the PAG group. However,

L-cys decreased the concentration of MDA in mucosa (Fig. 5A). The GSH content in the mucosa

decreased in the GI-R, PAG and L-cys groups. However, the reduction

of GSH content in the L-cys group was less than that in the PAG

group (P<0.05; Fig. 5B).

| Figure 5.Effects of PAG and L-cys on (A) MDA

and (B) GSH content in gastric mucosa from rats subjected to

gastric ischemia-reperfusion (GIR). Male Sprague-Dawley rats were

intraperitoneally injected with the H2S synthetase

blocker PAG (50 mg/kg) or L-cys (50 mg/kg) for 7 days before the

celiac arteries were clamped for 30 min ischemia and then

reperfused for 60 min. Sham group, age-matched rats with

physiological solute treatment but no GI-R procedure; GI-R group,

age-matched rats with physiological solute treatment followed by

the GI-R procedure; PAG group, rats intraperitoneally injected with

PAG and then subjected to the GI-R procedure; L-cys group, rats

intraperitoneally injected with L-cys and then subjected to the

GI-R procedure. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD),

n=8. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. the sham

group; #P<0.05 vs. the GI-R group;

ΔP<0.05, ΔΔP<0.01 vs. the PAG group.

PAG, DL-propargylglycine; L-cys, L-cysteine; H2S,

hydrogen sulfide; MDA, malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione. |

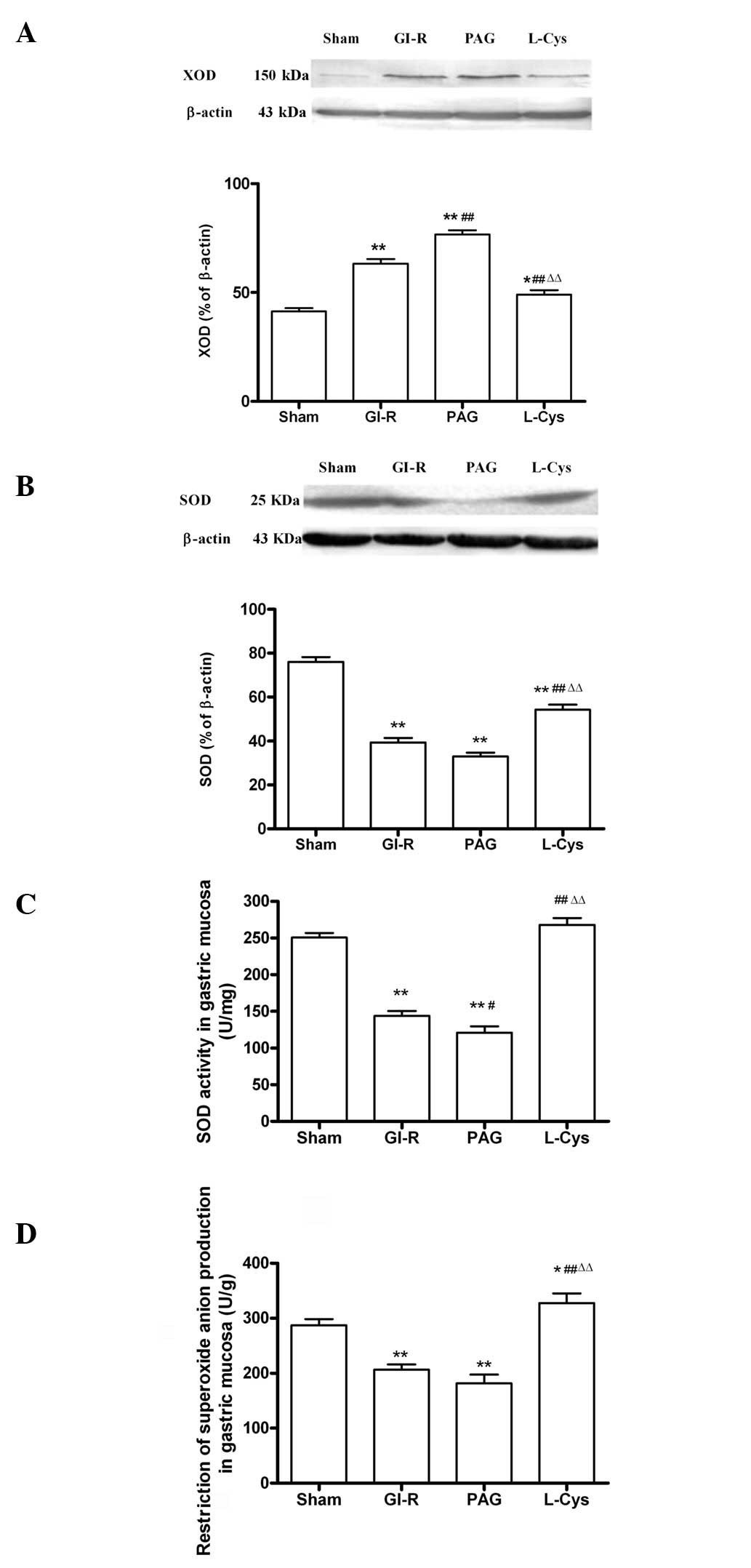

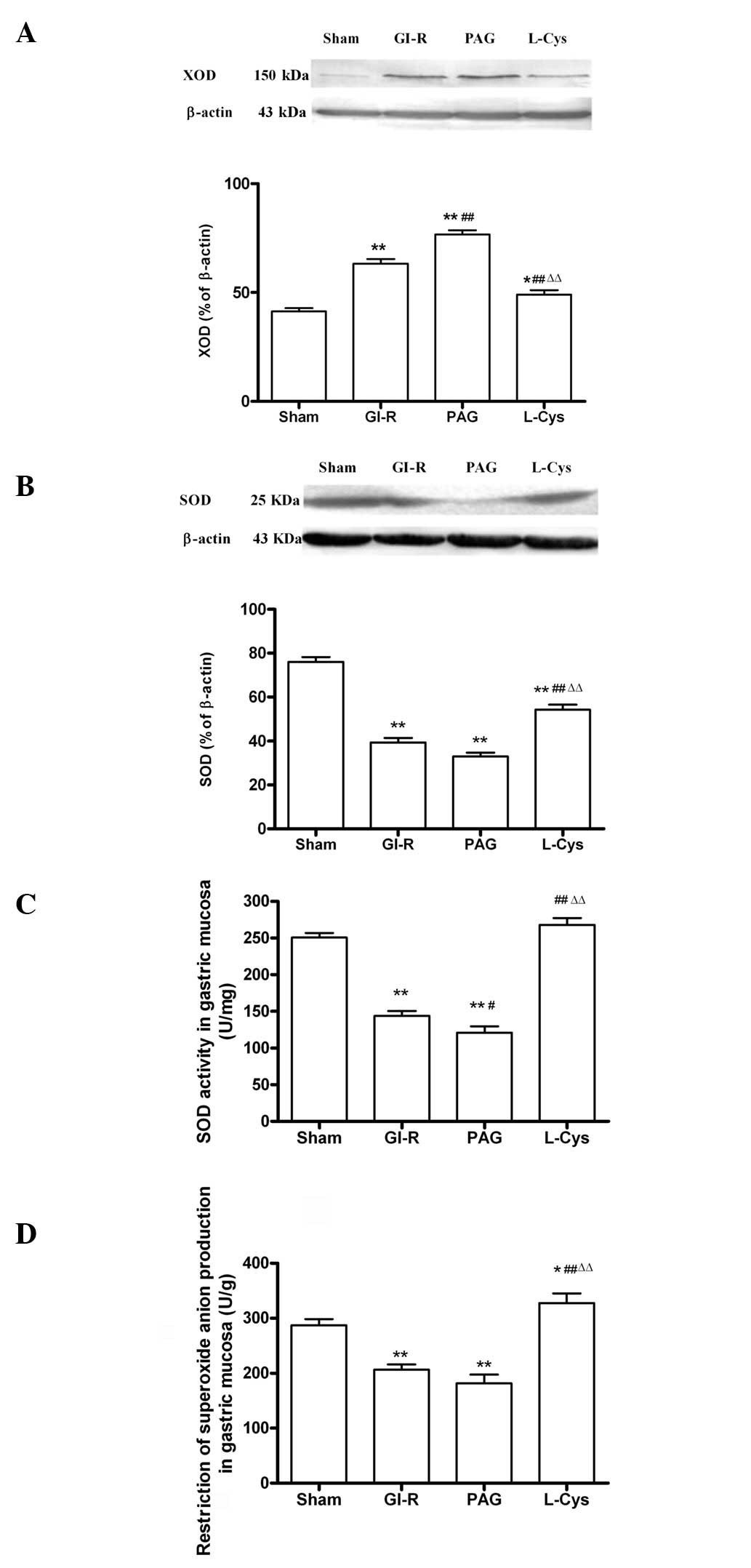

XOD and SOD expression, SOD activity and

inhibition of O2− production in the gastric

mucosa

Compared with the sham group (P<0.01; Fig. 6A), the expression level of XOD

markedly increased in the GI-R and PAG groups; while the SOD

expression in the GI-R and PAG groups decreased compared with the

sham group (P<0.01; Fig. 6B).

Compared with the GI-R group, L-cys downregulated XOD (P<0.01)

and upregulated SOD (P<0.01). Additionally, the activity of SOD

was decreased in the GI-R and PAG groups and the effects of GI-R

were attenuated by L-cys (P<0.01; Fig. 6C), as was the inhibition of

O2− production (Fig. 6D).

| Figure 6.Alteration of oxidative stress in

gastric mucosal tissue from rats subjected to 30 min gastric

ischemia and 60 min reperfusion (GI-R). (A) Effects of PAG and

L-cys on XOD expression in gastric mucosal tissue induced by GI-R

(n=3). (B) Effects of PAG and L-cys on SOD expression in gastric

mucosal tissue induced by GI-R (n=3). β-actin was used to normalize

for loading variations. (C) Effects of PAG and L-cys on SOD

activity in gastric mucosal tissue induced by GI-R (n=8). (D)

Effects of PAG and L-cys on the alteration of

O2− production in gastric mucosal tissue

induced by GI-R. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=8) were

intraperitoneally injected with the H2S synthetase

blocker PAG (50 mg/kg) or L-cys (50 mg/kg) for 7 days before the

celiac arteries were clamped for 30 min ischemia and then

reperfused for 60 min. Sham group, age-matched rats with

physiological solute treatment but no GI-R procedure; GI-R group,

age-matched rats with physiological solute treatment followed by

the GI-R procedure; PAG group, rats intraperitoneally injected with

PAG and then subjected to the GI-R procedure; L-cys group, rats

intraperitoneally injected with L-cys and then subjected to the

GI-R procedure. Data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

*P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. the sham group,

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. the GI-R group,

ΔΔP<0.01 vs. the PAG group. PAG, DL-propargylglycine;

L-cys, L-cysteine; H2S, hydrogen sulfide; XOD, xanthine

oxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase. |

Discussion

The occurrence of GI-R injury is related to a number

of factors, including excessive production of oxygen free radicals

in the mucosa (14), leukocyte

infiltration (15) and decreased

release of nitric oxide (16).

Oxidative stress induced by high levels of active oxygen plays a

major role in GI-R injury. Excess production of oxygen free

radicals is a major initiating factor and an independent pathogenic

factor of GI-R injury (17,18).

Therefore, investigating how to decrease oxidative stress is

essential for developing means of protecting the gastric mucosa

from attack by deleterious factors.

H2S is well-known as a toxic gas with the

smell of rotten eggs. Nevertheless, with the increasing interest in

endogenous gaseous signaling molecules, it has been shown that

endogenous H2S regulates a range of physiological and

pathological processes in the nervous, digestive and cardiovascular

systems (19–22). Hence, H2S is considered

to be a physiologically important molecule and a gaseous mediator.

In mammals, endogenous H2S is generated from L-cys under

the catalysis of total CBS and CSE, 1/3 of which is in the form of

gas while 2/3 is in the form of NaHS. NaHS dissociates in

vivo into sodium ions and sulfhydryl group ions and the latter

bind with hydrogen ions to generate H2S. Thus,

H2S and NaHS are in dynamic equilibrium (17). L-cys administration is

cardioprotective through enhanced myocardial H2S

generation as a result of CSE activation, which is attenuated by

the selective CSE enzyme inhibitor, PAG (23). Meanwhile, H2S protects

brain endothelial cells from oxidative stress (24). In this study, we identified that in

rats pretreated with a H2S synthetase blocker (PAG, 50

mg/kg/day) for 7 days, significant hemorrhage, edema and erosions

were observed in the surface of the gastric mucosa, as well as in

the GI-R group. However, pretreatment with L-cys, the precursor of

H2S, protected the mucosa from the damage induced by

GI-R (Fig. 1). The same results

were observed for gastric damage scores. After blocking the

production of H2S with PAG, gastric mucosal ulceration

and the number of hemorrhage sites significantly increased, a

number of mucosal cells died, erosion sites formed and significant

edema and inflammatory infiltration appeared in the submucosa. The

signs of gastric mucosal injury were markedly alleviated by the

continuous administration of L-cys (Fig. 2). Although there was no significant

change in the H2S concentration in serum, PAG

successfully inhibited H2S production (Fig. 3) and CSE expression (Fig. 4) in the gastric mucosa, while L-cys

did not cause any evident change in H2S. Endogenous

H2S in the gastric mucosa plays an important role in the

protective effect against GI-R injury. Whiteman et al

identified that in the rat brain, H2S protects neurons

from injury by eliminating oxygen free radicals (5).

A number of studies have reported that oxidative

stress plays a pivotal role in GI-R injury. In the GI-R process,

lipid peroxidation is induced by an increased number of oxygen free

radicals. A change of MDA content is a measure of the degree of

damage caused by membrane lipid peroxidation. In our study, when

H2S was inhibited by PAG, lipid peroxidation increased

in the gastric mucosa since the MDA content was higher than that of

the GI-R group. However, when H2S was increased, the MDA

level decreased (Fig. 5A). This

result is consistent with the findings on the effect of

H2S on a rat model of myocardial infarction (25). Furthermore, GSH is the major

endogenous antioxidant produced by mammalian cells, preventing

damage to important cellular components caused by reactive oxygen

species (26). We identified that

L-cys increased the GSH content when compared with the PAG group

(Fig. 5B). When H2S

production was blocked, MDA levels increased. Additionally,

increasing endogenous H2S production reduced MDA content

since GSH levels were enhanced. This suggests that endogenous

H2S protects the integrity of the gastric mucosa by

increasing GSH and decreasing MDA content. This is consistent with

the finding that H2S has anti-oxidative effects by

promoting the transfer of cystine into cells and improving the

cellular synthesis of GSH (27).

The antioxidant action of H2S plays an important role

during GI-R.

During the reperfusion period following ischemia or

hypoxia, large amounts of superoxide and O2−

are generated from xanthine and hypoxanthine under the action of

XOD. XOD is considered the most important source of oxygen free

radicals (28). Meanwhile, living

tissues are endowed with innate antioxidant defense mechanisms,

namely antioxidative enzymes. When the amount of active oxygen

exceeds the scavenging capacity of the antioxidant defensive

system, including SOD, the immunological function of the

gastrointestinal tract is severely damaged by free radicals, which

results in tissue and organ injury (29). In this study, we identified that

blocking the synthesis of endogenous H2S significantly

increased the expression of XOD (Fig.

6A), causing oxygen free radical overproduction in the gastric

mucosa. Nevertheless, the activity of the antioxidative enzyme,

SOD, was enhanced by increasing H2S in rats pretreated

with L-cys (Fig. 6B and C). As a

result, the ability to inhibit O2− production

was clearly reduced due to the reduction of endogenous

H2S by PAG (Fig. 6D).

The protective role of H2S against oxidative stress has

also been clarified in rat gastric mucosal epithelium (30).

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that

endogenous H2S protects the gastric mucosa against

ischemia and reperfusion injury. Selective inhibition of the CSE

enzyme enhances the injury following GI-R. However, L-cys

administration attenuates the harmful effects of GI-R through

activation of CSE to increase H2S generation. The

gastroprotective effect of endogenous H2S against GI-R

may be mediated by enhancing the anti-oxidative capacity through

increasing GSH and SOD to reduce free radical production.

Abbreviations:

|

H2S

|

hydrogen sulfide;

|

|

GI-R

|

gastric ischemiareperfusion;

|

|

PAG

|

DL-propargylglycine;

|

|

MDA

|

malondialdehyde;

|

|

GSH

|

glutathione;

|

|

SOD

|

superoxide dismutase;

|

|

CSE

|

cystathionine γ-lyase;

|

|

XOD

|

xanthine oxidase;

|

|

L-cys

|

L-cysteine

|

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants

from the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province

(BK2009088). The authors thank Dr Jinsong Bian for critical reading

of this manuscript and Dr Iain C Bruce for refining the English

language.

References

|

1.

|

Gross GJ and Auchampach JA: Reperfusion

injury: does it exist? J Mol Cell Cardiol. 42:12–18. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2.

|

Wang R: Two’s company, three’s a crowd:

can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter?

FASEB J. 16:1792–1798. 2002.

|

|

3.

|

Tokuda K, Kida K, Marutani E, Crimi E,

Bougaki M, Khatri A, Kimura H and Ichinose F: Inhaled hydrogen

sulfide prevents endotoxin-induced systemic inflammation and

improves survival by altering sulfide metabolism in mice. Antioxid

Redox Signal. 17:11–21. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Jiang LH, Luo X, He W, Huang XX and Cheng

TT: Effects of exogenous hydrogen sulfide on apoptosis proteins and

oxidative stress in the hippocampus of rats undergoing heroin

withdrawal. Arch Pharm Res. 34:2155–2162. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Whiteman M, Armstrong JS, Chu SH, Jia-Ling

S, Wong BS, Cheung NS, Halliwell B and Moore PK: The novel

neuro-modulator hydrogen sulfide: an endogenous peroxynitrite

‘scavenger’? J Neurochem. 90:765–768. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Sivarajah A, McDonald MC and Thiemermann

C: The production of hydrogen sulfide limits myocardial ischemia

and reperfusion injury and contributes to the cardioprotective

effects of preconditioning with endotoxin, but not ischemia in the

rat. Shock. 26:154–161. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Tay AS, Hu LF, Lu M, Wong PT and Bian JS:

Hydrogen sulfide protects neurons against hypoxic injury via

stimulation of ATP-sensitive potassium channel/protein kinase

C/extra-cellular signal-regulated kinase/heat shock protein 90

pathway. Neuroscience. 167:277–286. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8.

|

Kang K, Zhao M, Jiang H, Tan G, Pan S and

Sun X: Role of hydrogen sulfide in hepatic

ischemia-reperfusion-induced injury in rats. Liver Transpl.

15:1306–1314. 2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Fu Z, Liu X, Geng B, Fang L and Tang C:

Hydrogen sulfide protects rat lung from ischemia-reperfusion

injury. Life Sci. 82:1196–1202. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Mard SA, Neisi N, Solgi G, Hassanpour M,

Darbor M and Maleki M: Gastroprotective effect of NaHS against

mucosal lesions induced by ischemia-reperfusion injury in rat. Dig

Dis Sci. 57:1496–1503. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Wada K, Kamisaki Y, Kitano M, Kishimoto Y,

Nakamoto K and Itoh T: A new gastric ulcer model induced by

ischemia-reperfusion in the rat: role of leukocytes on ulceration

in rat stomach. Life Sci. 59:PL295–PL301. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Pan TT, Feng ZN, Lee SW, Moore PK and Bian

JS: Endogenous hydrogen sulfide contributes to the cardioprotection

by metabolic inhibition preconditioning in the rat ventricular

myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 40:119–130. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Masuda E, Kawano S, Nagano K, Tsuji S,

Takei Y, Hayashi N, Tsujii M, Oshita M, Michida T, Kobayashi I, et

al: Role of endogenous endothelin in pathogenesis of

ethanol-induced gastric mucosal injury in rats. Am J Physiol.

265:G474–G481. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Kwiecień S, Brzozowski T and Konturek SJ:

Effects of reactive oxygen species action on gastric mucosa in

various models of mucosal injury. J Physiol Pharmacol. 53:39–50.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Andrews FJ, Malcontenti-Wilson C and

O’Brien PE: Polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration into gastric

mucosa after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol. 266:G48–G54.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Wada K, Kamisaki Y, Ohkura T, Kanda G,

Nakamoto K, Kishimoto Y, Ashida K and Itoh T: Direct measurement of

nitric oxide release in gastric mucosa during ischemia-reperfusion

in rats. Am J Physiol. 274:G465–G471. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Ishii M, Shimizu S, Nawata S, Kiuchi Y and

Yamamoto T: Involvement of reactive oxygen species and nitric oxide

in gastric ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats: protective effect

of tetrahydrobiopterin. Dig Dis Sci. 45:93–98. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Itoh M and Guth PH: Role of oxygen-derived

free radicals in hemorrhagic shock-induced gastric lesions in the

rat. Gastroenterology. 88:1162–1167. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

El Eter E, Hagar HH, Al-Tuwaijiri A and

Arafa M: Nuclear factor-kappaB inhibition by

pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate attenuates gastric ischemia-reperfusion

injury in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 83:483–492.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Kimura Y, Dargusch R, Schubert D and

Kimura H: Hydrogen sulfide protects HT22 neuronal cells from

oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal. 8:661–670. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Kimura Y and Kimura H: Hydrogen sulfide

protects neurons from oxidative stress. FASEB J. 18:1165–1167.

2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Zhang Z, Huang H, Liu P, Tang C and Wang

J: Hydrogen sulfide contributes to cardioprotection during

ischemia-reperfusion injury by opening K ATP channels. Can J

Physiol Pharmacol. 85:1248–1253. 2007. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Elsey DJ, Fowkes RC and Baxter GF:

L-cysteine stimulates hydrogen sulfide synthesis in myocardium

associated with attenuation of ischmia-reperfusion injury. J

Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 15:53–59. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Tyagi N, Moshal KS, Sen U, Vacek TP, Kumar

M, Hughes WM Jr, Kundu S and Tyagi SC: H2S protects

against methionine-induced oxidative stress in brain endothelial

cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 11:25–33. 2009.

|

|

25.

|

Zhu YZ, Wang ZJ, Ho P, Loke YY, Zhu YC,

Huang SH, Tan CS, Whiteman M, Lu J and Moore PK: Hydrogen sulfide

and its possible roles in myocardial ischemia in experimental rats.

J Appl Physiol. 102:261–268. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Pompella A, Visvikis A, Paolicchi A, De

Tata V and Casini AF: The changing faces of glutathione, a cellular

protagonist. Biochem Pharmacol. 66:1499–1503. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Liu H, Bai XB, Shi S and Cao YX: Hydrogen

sulfide protects from intestinal ischaemia-reperfusion injury in

rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 61:207–212. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Margaritis EV, Yanni AE, Agrogiannis G,

Liarakos N, Pantopoulou A, Vlachos I, Papachristodoulou A,

Korkolopoulou P, Patsouris E, Kostakis M, Perrea DN and Kostakis A:

Effects of oral administration of l-arginine, l-NAME and

allopurinol on intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Life

Sci. 88:1070–1076. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Wang T, Leng YF and Zhang Y, Xue X, Kang

YQ and Zhang Y: Oxidative stress and hypoxia-induced factor 1alpha

expression in gastric ischemia. World J Gastroenterol.

17:1915–1922. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Yonezawa D, Sekiguchi F, Miyamoto M,

Taniguchi E, Honjo M, Masuko T, Nishikawa H and Kawabata A: A

protective role of hydrogen sulfide against oxidative stress in rat

gastric mucosal epithelium. Toxicology. 241:11–18. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|