Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) is one of the most

common diseases and has a serious impact on human health and safety

(1). It has become one of the top

causes of mortality in China. The prevalence of CHD is increasing

and sudden mortality is often due to this sudden disease. Detecting

CHD as early as possible before clinical symptoms appear is

important. Selective X-ray coronary angiography (SCA) is one of the

standard tests for CHD; however,it has several disadvantages,

including high-cost, invasive diagnosis and the performance of the

procedure necessitates considerable time and skill of highly

trained physicians. In the past few years, non-invasive diagnosis

of CHD has made great progress. With the improvement of

computerized tomography (CT) hardware and software technology,

64-multislice spiral CT (64-MSCT) CT angiography (CTA) has become a

common, non-invasive diagnostic method. In this study, we assessed

the clinical application of 64-MSCT CTA compared with SCA, based on

previous randomized studies (2,3).

Patients and methods

Patient characteristics

A total of 95 patients with suspected obstructive

coronary artery disease received 64-MSCT. Of these, 67 patients

were identified to have coronary stenosis. There were 43 males and

24 females, aged 41–81 years (average age, 65 years) with regular

sinus rhythm. For patients with a fast heart rate, the rhythm could

be controlled below 70 bpm, without Betaloc allergy effects. The

study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration II

and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Harbin

Medical University. All patients provided written informed consent

which was signed by the patient or their families.

Methods

The heart cover area was set at 120 mm with a fast

rotation speed of 0.35 sec per rotation. The mean pitch of the

heart scan was 0.23. The detector width was 64×0.625 mm and the

time of the heart scan was 4.57 sec. The blood circulation time was

evaluated by a test bolus. The injection rate of the contrast media

was 5 ml/sec. The range of the scan covered the whole heart. The

patient was instructed to maintain an inspiratory breath hold. The

whole process was performed by an interventional cardiologist.

Results

All 95 patients received 64-MSCT. All the main blood

vessels and major branches were smooth and there was no stenosis in

18 patients. Coronary myocardial bridge (CMB) was detected in 10

patients. Among the 67 patients with coronary stenosis, we detected

mild coronary stenosis (<50%) in 19 patients, moderate coronary

stenosis (50–70%) in 26 patients and severe coronary stenosis

(>75%) in 22 patients. Of the 18 patients without coronary

stenosis 11 presented symptoms, including chest distress and chest

pain. The SCA results revealed no coronary stenosis. In addition, 4

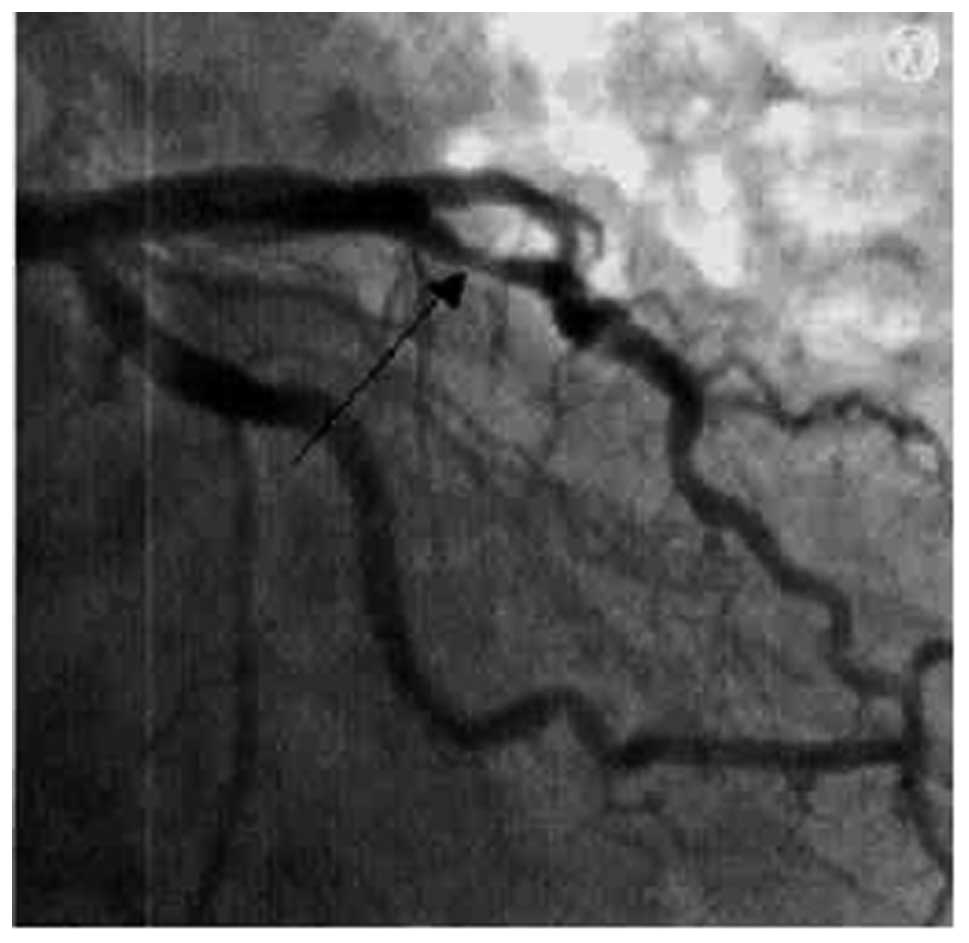

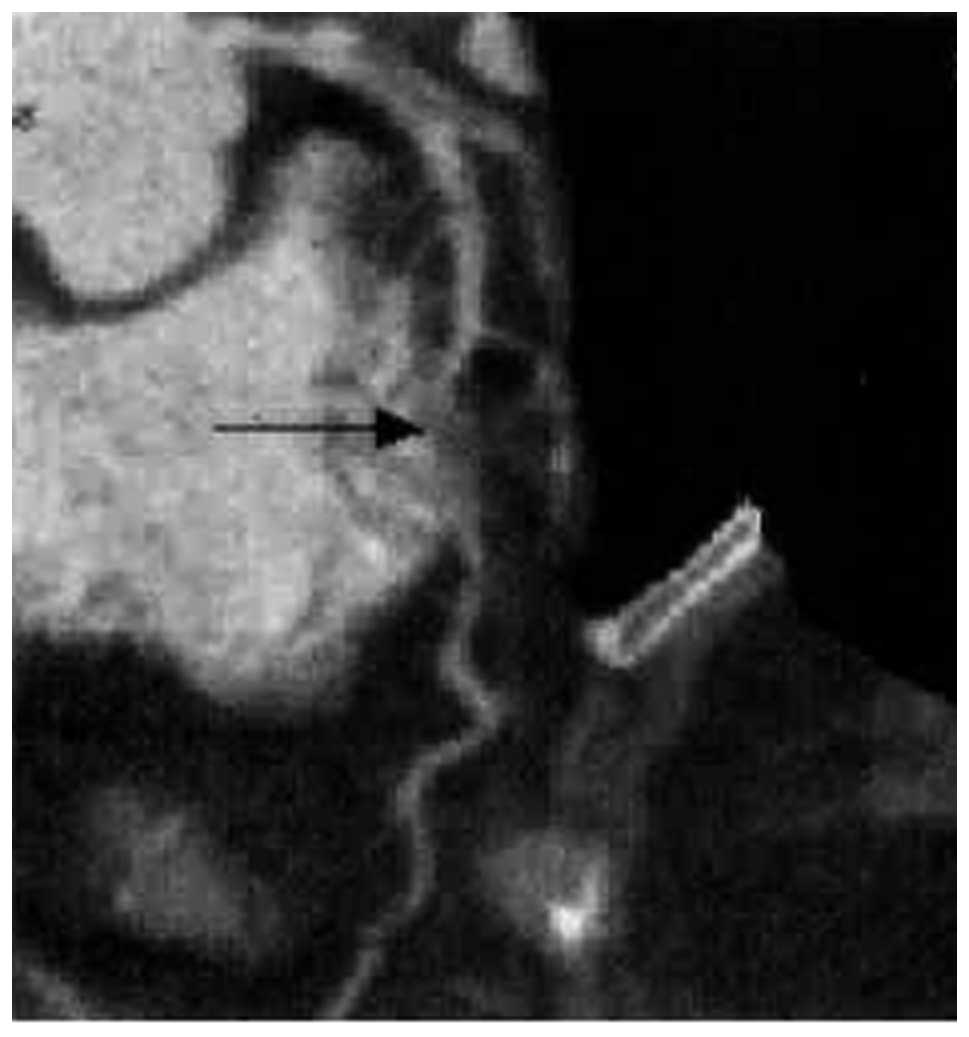

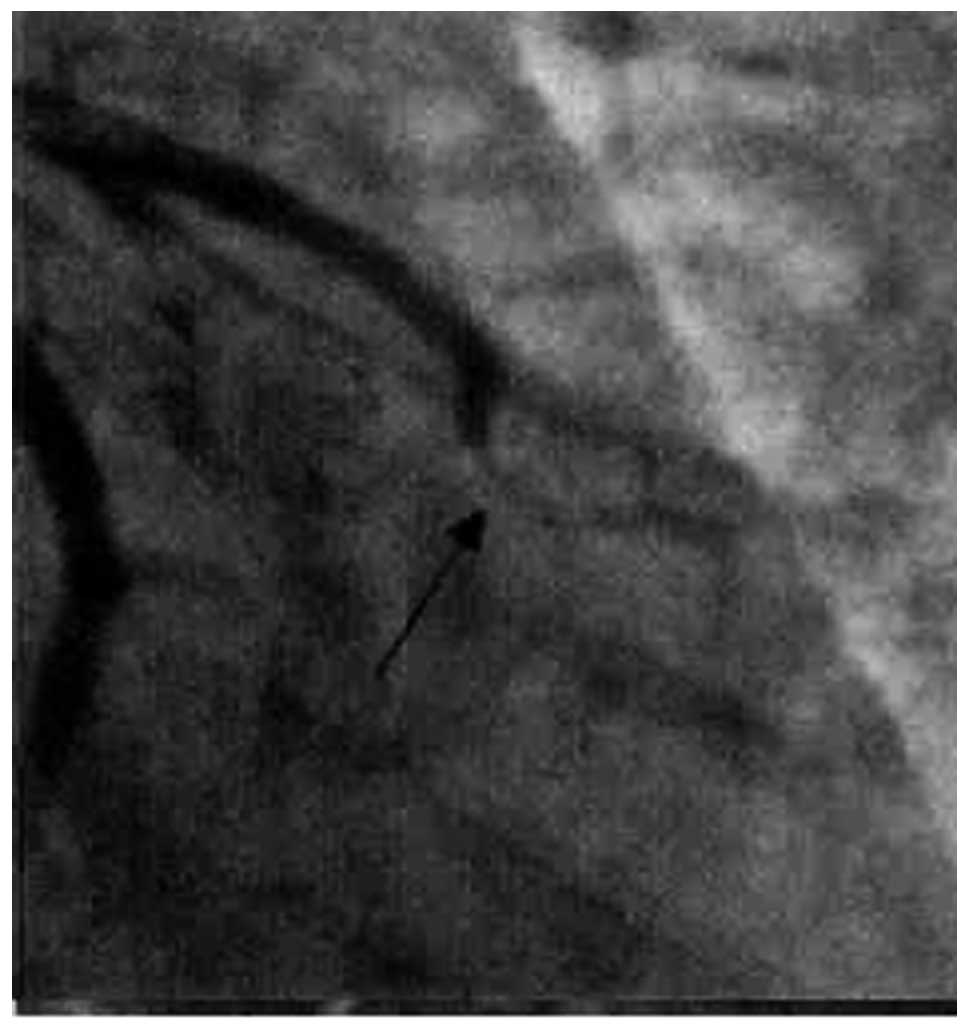

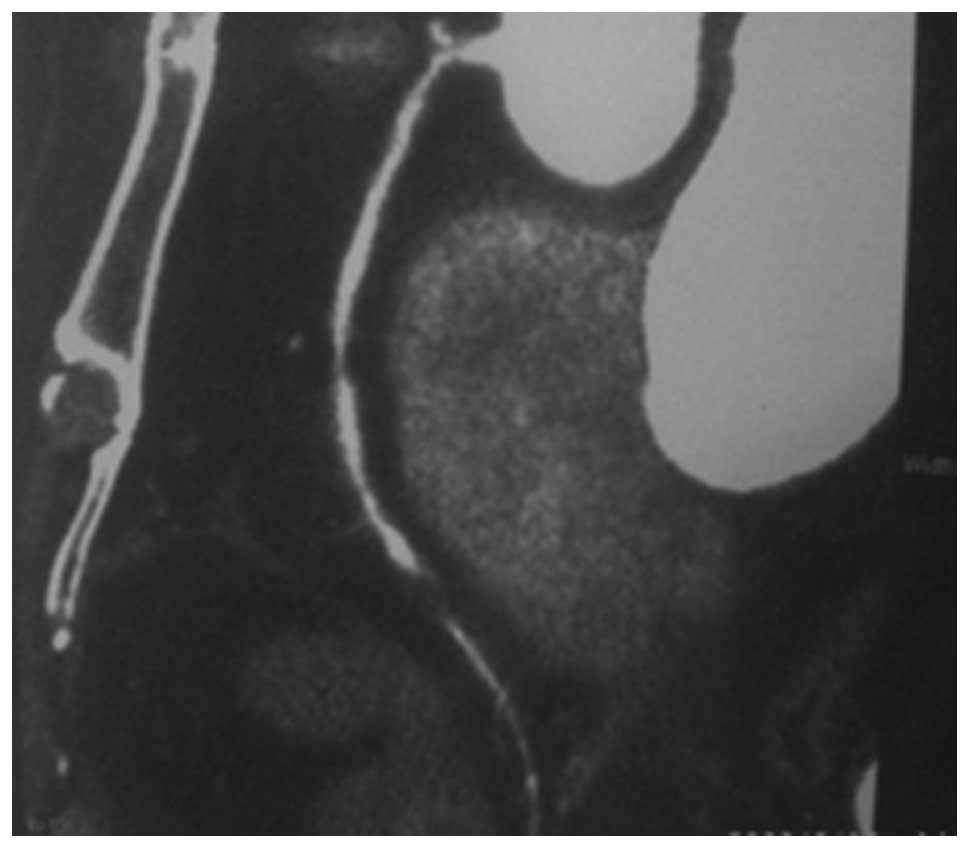

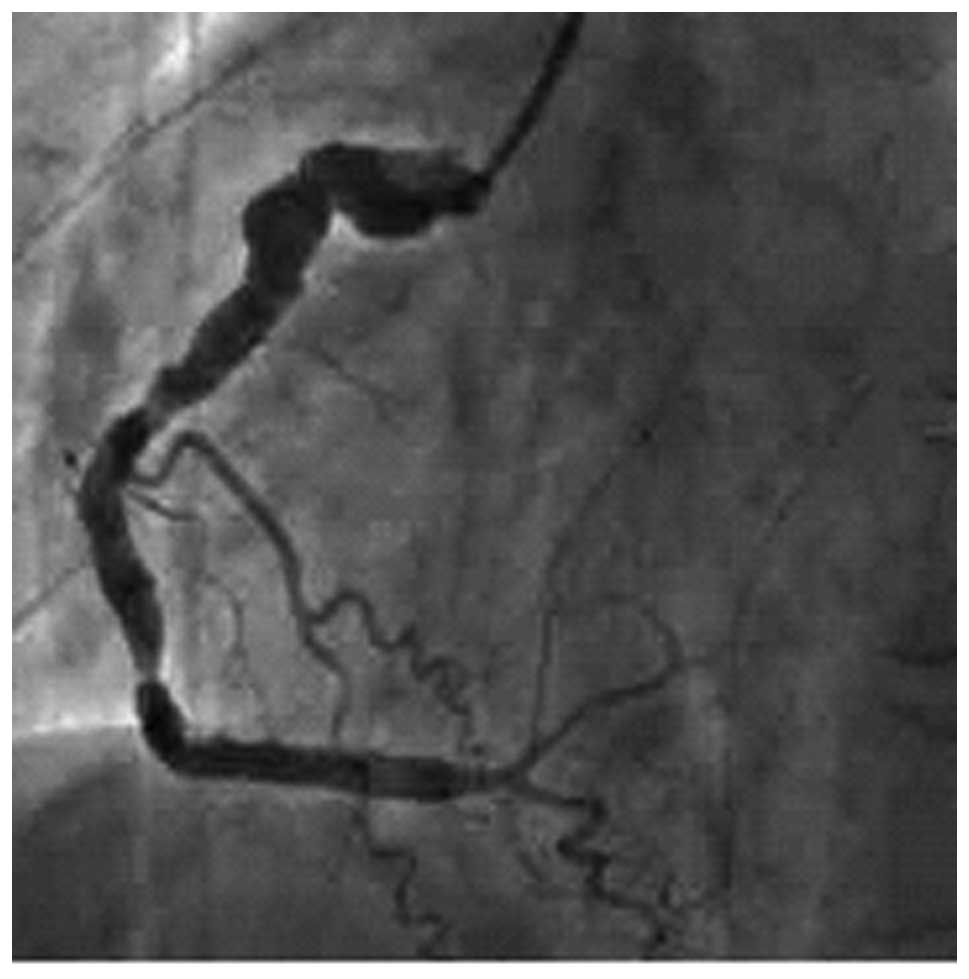

of the 5 CMB patients were diagnosed with SCA (Figs. 1 and 2) and 1 patient was diagnosed with severe

coronary stenosis (Figs. 3 and

4).

Among the patients with coronary stenosis, the SCA

results of 5 patients with mild coronary stenosis revealed that the

level of coronary stenosis was ∼30, 60, 30, 30 and 30%,

respectively. In 9 of the 26 patients with moderate coronary

stenosis the SCA results were consistent with the 64-MSCT results.

However, 17 patients had severe coronary stenosis and percutaneous

transluminal coronary intervention treatment confirmed the main and

major branch of the diseased blood vessel for these patients with

severe coronary stenosis (Figs. 5

and 6).

Discussion

CHD is one of the main factors threatening human

health and it is also one of the main causes of mortality in China.

Diagnosing coronary stenosis as early as possible and initiating

treatment helps to prevent disease progression. The most common

clinical methods for coronary stenosis are 64-MSCT CTA and SCA, and

SCA is more accurate at this stage. SCA is not only used for

diagnosis, but also for intervention therapy. However, the conduit

method has certain risks due to the invasive property, particularly

for patients who are not suitable for intervention therapy.

Additionally, SCA often increases the financial burden and certain

risks. Therefore, the reliable noninvasive 64-MSCT CTA has

attracted attention. In the past few years, the 64-MSCT hardware

has improved, the scanning time has reduced dramatically and the

time and spatial resolution have increased rapidly. In addition,

the breath artifact is avoided when the heart rate is <70 bpm

and the heart motion artifact is avoided. It also provides an

improved image quality, which clearly shows the coronary artery.

Therefore, 64-MSCT CTA is a common and popular technique (4).

In 64 patients with CHD, 64-MSCT CTA was performed

and the results on coronary stenosis reveal no difference when

compared with SCA diagnosis. Therefore, 64-MSCT CTA may be used

clinically to identify a true negative value when the symptoms of

CHD do not agree with the electrocardiogram (ECG) diagnosis

(5). A CMB is a band of heart

muscle that lies on top of a coronary artery, instead of underneath

it. With a CMB, part of a coronary artery dips into and underneath

the heart muscle and then comes back out again (6). The band of muscle that lies on top of

the coronary artery is called a bridge. With research on anatomy,

pathology and blood hemodynamics, it was identified that a CMB may

cause myocardium ischemia under certain conditions. The diagnosis

and therapy of CMB is becoming increasingly important. SCA is a

classic method for diagnosis, which shows a milking-like effect,

where the CMB is squeezed by contraction of surrounding muscle and

the constriction disappears during diastole. The 64-MSCT CTA method

displays the coronary artery and surrounding myocardial area;

therefore, it has a better diagnostic result than SCA on CMB.

Furthermore, 64-MSCT CTA avoids a false positive diagnosis. CMB is

often misdiagnosed as lumen stenosis and stent implantation is

applied; however, this may cause the lumen to break. Therefore,

64-MSCT CTA has become a better option for diagnosing CMB (7,8).

In this controlled study, we compared 64-MSCT CTA

and SCA diagnostic results and identified that SCA is capable of

diagnosing a mild or moderate coronary stenosis and 64-MSCT CTA

detects a mild coronary stenosis. We suggest that when 64-MSCT CTA

detects a mild coronary stenosis with typical symptoms and the ECG

shows no clear evolvement, a conservative therapy should be

performed and the patient’s condition strictly monitored during the

therapy. Then, SCA should only be performed when necessary.

In this study, when comparing moderate coronary

stenosis detected by 64-MSCT CTA with SCA diagnosis for the same

patients, SCA revealed that more than half of the patients had

severe coronary stenosis and required coronary stent therapy.

Therefore, we suggest that SCA is performed when a moderate

coronary stenosis is detected by 64-MSCT CTA, to prevent delay in

treatment and possible heart infarction. For severe coronary

stenosis, detected by 64-MSCT CTA, we observed a clear agreement

between 64-MSCT CTA and SCA diagnosis (9). In summary we suggest that 64-MSCT CTA

is used at the early stages for those with no CHD symptoms, mild

symptoms or no significant variation in ECG results. It is not

necessary to perform a check with SCA if nothing shows up from the

64-MSCT CTA diagnosis. For those patients who have clear symptoms,

significant variation in ECG results and 64-MSCT CTA diagnosis

reveals moderate to severe coronary stenosis, a further SCA check

is necessary. A stent implantation therapy should be performed when

the coronary stenosis level reaches ≥70% (10).

Further development is required for 64-MSCT CTA to

improve the time resolution and spatial resolution. This enables an

advanced CT detector to reach an equal quality with SCA

(0.2×0.2×0.2mm) (11). With the

development of tube rotation speed and re-build technology, the

non-invasive CTA is considered the next generation method of

SCA.

References

|

1.

|

Schroeder S, Kopp AF, Baumbach A, et al:

Noninvasive detection and evaluation of atheroscleotic coronary

plaques with multislice computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol.

37:1430–1435. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Li P, Xu K, Li S, et al: Impact of heart

rate on image quality of 16-slice spiral CT coronary angiography

and optimization of image reconstruction window. Chin J Interv

Imaging Ther. 3:18–22. 2006.(In Chinese).

|

|

3.

|

Nieman K, Cademartiri F, Lemos PA, et al:

Reliable noninvasive coronary angiography with fast submillimeter

multislice spiral computed tomography. Circulation. 106:2051–2054.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Wang ZQ, Yang ZQ, Zhu H, et al: Detection

of coronary artery stenoses using 16-slice spiral CT: comparison

with quantitative coronary angiography. J Comput Tomogr. 3:7–11.

2003.

|

|

5.

|

Xue H, Zhang Z, Jin Z, Lin S, Zhao W,

Zhang L and Zhang S: Recommended orientations of the MSCT coronary

angiography. Chinese J Med Imaging. 12:324–327. 2004.(In

Chinese).

|

|

6.

|

Konen E, Goitein O, Sternik L, et al: The

prevalence and anatomical patterns of intramuscular coronary

arteries: a coronary computed tomography angiographic study. J Am

Coll Cardiol. 49:587–593. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Zhang G, Qian J, Fan B, et al: The impact

of myocardial bridge on coronary flow reverse. Chin J Cardiol.

30:279–281. 2002.(In Chinese).

|

|

8.

|

Zhang G and Ge J: Status of clinical

research ofmyocardial bridge. Chin J Intervent Cardiol. 10:52–54.

2002.(In Chinese).

|

|

9.

|

Heuschmid M, Kuettner A, Schroeder S, et

al: ECG-gated 16-MDCT of the coronary arteries: assessment of image

quality and accuracy in detecting stenoses. AJR Am J Roentgenol.

184:1413–1419. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Xu Y and Lv J: Analysis of 106 cases with

CTA 64-MSCT. Chinese Med J Metallurg Ind. 23:1012006.(In

Chinese).

|

|

11.

|

Morgan-Hughes GJ, Roobottom CA, Owens PE

and Marshall AJ: Highly accurate coronary angiography with

submillimetre, 16 slice computed tomography. Heart. 91:308–313.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|