Introduction

The rate of emergence of drug-resistant strains has

been increasing in recent years owing to the widespread and

inappropriate use of conventional antibiotics. This is significant

threat to human health (1), and the

development of novel antimicrobial agents that are effective

against antibiotic-resistance microbes is urgently required

(2). Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs)

are important components of the innate host defense system and are

present in virtually all species of life. AMPs have broad spectrum

activity against bacteria, fungi, viruses, parasites and even

tumors, and have exhibited a similar efficiency against strains

that are resistant and susceptible to antibiotics (3). Since they exert nonspecific

membrane-lytic activities, it is extremely difficult for bacteria

to develop resistance to AMPs. Therefore, AMPs have been regarded

with increasing interest for development as novel therapeutic

agents for the control and prevention of infectious diseases,

particularly those caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria

(4).

Among the AMPs, cathelicidins are one of the most

prominent families of host defence peptides and are recognized as

having a role in the defence against microbial invasion (5). The majority of cathelicidins are

differentially expressed in a variety of tissues and exhibit

broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity against gram-negative and

gram-positive bacteria, fungi, protozoa and enveloped viruses

(6,7). Fowlicidin-2 is a novel member of the

cathelicidins family that was identified in chicken (8). The peptide has previously been shown to

exert highly potent antibacterial and lipopolysaccharide

(LPS)-neutralizing activities (8,9), and is

among the most efficacious cathelicidins to have been reported

(8). Due to its broad-spectrum and

salt-insensitive antibacterial activities, as well as its potent

LPS-neutralizing activity (8),

fowlicidin-2 may be an excellent candidate as a novel antimicrobial

and antisepsis agent.

There are three pathways for AMP production:

Extraction from natural resources, chemical synthesis and

recombinant expression. Due to the complexity, low-yield and high

cost of chemical peptide synthesis (10), genetic engineering technology using

microorganisms as host cells to express AMPs may be a more

efficient method for AMP production. The methylotrophic yeast

Pichia pastoris has become widely used as a heterologous

gene expression system (11). Yeasts

have become increasingly important in genetic engineering due to

the ease by which they may be genetically manipulated, their

ability to grow rapidly in inexpensive medium to high cell

densities and their capability for complex post-translational

modifications, including folding, disulfide bridge formation and

glycosylation (12,13). The slow production of fowlicidin-2

has been, to date, a bottleneck for its development in scientific

and industrial research. In our previous study, fowlicidin-2 was

expressed in Escherichia coli (14); however, the yield (~6 mg/l) and the

cost of production requires further improvement to meet the needs

of industrial production. In the present study, fowlicidin-2 was

recombinantly expressed using a P. pastoris expression

system, and the bioactivity of the recombinant peptide was

investigated in vitro.

Materials and methods

Strains, vectors, reagents and

enzymes

The expression host, P. pastoris X-33, and

the pPICZα-A expression vector were purchased from Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc. (Waltham, MA, USA). E. coli DH5α, E.

coli 25922, Staphylococcus aureus 29213, Pseudomonas

aeruginosa 27853 and Salmonella typhimurium C77-31 were

preserved in our laboratory. A375 human malignant melanoma cells

and RAW264.7 mice macrophages were purchased from Type Culture

Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China).

Chick embryo fibroblasts (CEFs) were isolated from 9-day-old

chicken embryos, provided by the Harbin Veterinary Research

Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Harbin,

China). The experimental protocol was reviewed and approved by the

ethics committee of the Hospital of Northeast Agricultural

University (NEAU; Harbin, China).

Construction of the expression

vector

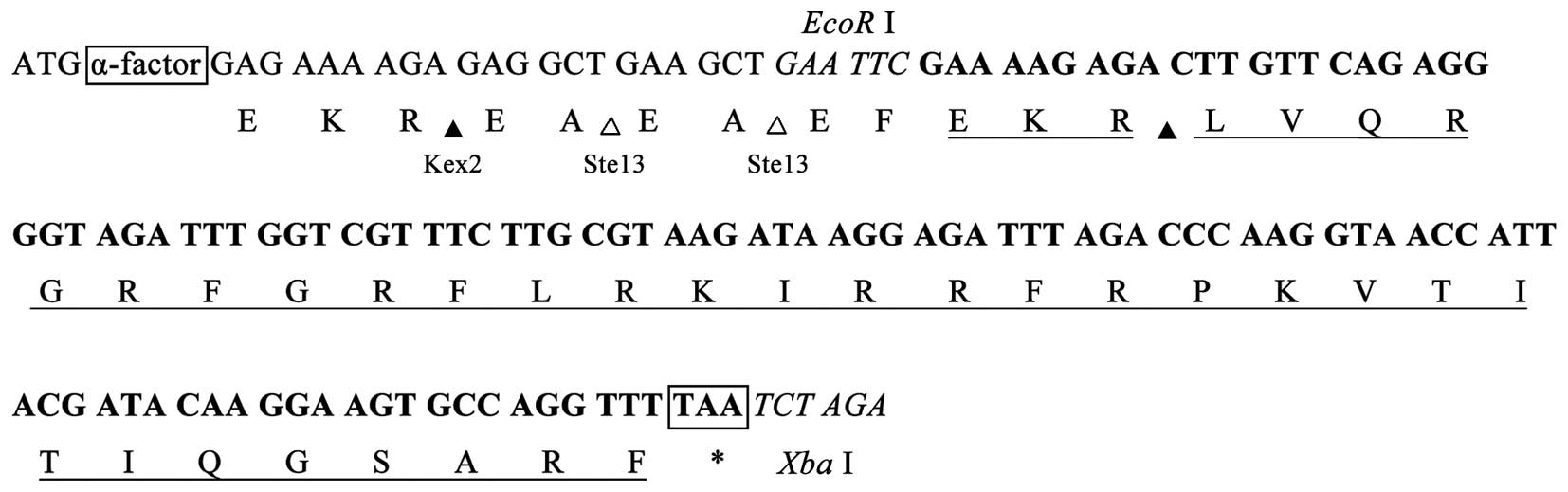

A DNA fragment encoding the mature peptide of

fowlicidin-2 was designed, using DNA software (version 2.0;

http://www.dna20.com) according to the codon bias

of the methylotrophic yeast P. pastoris. The fragment was

constructed using two complementary oligonucleotides (oligos), as

follows: Sense, 5′-GAATTC

GAAAAGAGACTTGTTCAGAGGGGTAGATTTGGTCGTTTCTTGCGTAAGATAAGGAGATTTAGACCCAAGGTAACCATTACGATACAAGGA

A G T G C C A G G T T T TAA T C T AGA-3′ and

antisense, 5′-TCTAGA

TTAAAACCTGGCACTTCCTTGTATCGTAATGGTTACCTTGGGTCTAAATCTCCTTATCTTACGCAAGAAACGACCAAATCTACCCCTCTGAACAAGTCTCTTTTC

GAATTC-3′. Restriction sites for EcoRI and

XbaI are indicated in the oligos in italics. A terminal TAA

codon is followed by the sequence encoding fowlicidin-2 in the

sense strand. GAAAAGAGA, as the codon for a glutamic acid, lysine

and arginine (EKR) sequence, provide the cleavage site of Kexin

protease 2 (Kex2) in the translated peptide (Fig. 1). The two complementary oligos were

synthesized chemically by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai,

China). A total of 20 µl of each sense and antisense oligos

solution (100 µm) were mixed, heated at 95°C for 2 min and cooled

down to room temperature. The annealed product was purified using

the gel extraction kit (cat. no. 28704; Qiagen, Beijing, China).

Following digestion by EcoRI and XbaI, the annealed

product was ligated using a DNA Ligation kit (cat. no. 6022;

version 2.1; Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China)

according to the manufacturer's instruction between the

EcoRI and XbaI sites of the pPICZα-A vector, which

contains the Saccharomyces cerevisiae α-factor secretion

signal and the alcohol oxidase 1 promoter. A total of 10 µl of the

resultant plasmid (30 ng) was added to 100 µl of competent E.

coli DH5α cells (Tiangen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) and

held on ice for 30 min prior to heat shocking at 42°C for 90 sec.

After incubation on ice for 2 min, the cells were diluted into 0.8

ml LB culture (0.5% yeast extract, 1% tryptone, 1% NaCl) (Hopebio,

Qindao, China) and cultured at 37°C for 30 min. Then, appropriate

dilutions were plated on LB plates (containing 20 µg/ml Zeocin) and

incubated for 12 h at 37°C (15).

Positive transformants were screened by colony polymerase chain

reaction (PCR) using a Taq PCR Mastermix kit (cat. no.

KT201; Qiagen) and the following primers: P1,

5′-GACTGGTTCCAATTGACAAGC-3′ and P2, 5′-GCAAATGGCATTCTGACATCC-3′.

The following thermal cycling conditions were used: 94°C for 5 min

followed by 32 cycles (95°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 30 sec and 72°C

for 1 min) and finally 72°C for a 5 min extension. Finally, they

were verified by DNA sequencing.

Transformation of P. pastoris and

selection of transformants

The pPICZα-A-fowlicidin-2 construct was linearized

using the SacI restriction enzyme and transformed into P.

pastoris X-33 cells by electroporation using a Gene Pulser

apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) in 0.2-cm

electroporation cuvettes (200 Ω, 25 µF, 1,500 V). The pPICZα-A

vector was similarly linearized and transformed into P.

pastoris X-33 as a negative control. The two types of

transformed P. pastoris were incubated at 30°C in YPD plates

(Hopebio) containing 1% yeast extract, 2% tryptone, 2% dextrose, 2%

agar and 100 µg/ml Zeocin (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). In order to determine the methanol-utilizing phenotype of

the transformants, all Zeocin-resistant transformants cultured in

YPD medium were selected on MD plates (1.34% YNB,

4×10−5% biotin, 2% dextrose and 2% agar) and MM plates

(1.34% YNB, 4×10−5% biotin, 0.5% methanol and 1.5% agar)

(both purchased from Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Zeocin+ Mut+ phenotype colonies were further

confirmed by colony-PCR using the P1 and P2 primers.

Heterologous expression of recombinant

fowlicidin-2 (rfowlicidin-2)

A total of 10 pPICZα-A-fowlicidin-2 transformants

were cultured at 30°C in a shaking flask containing 20 ml buffered

glycerol complex medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 0.3%

K2HPO4, 1.18% KH2PO4,

1.34% YNB, 4×10−5% biotin, 1% glycerol, pH 6.0) to

optical density (OD)600=2.0–6.0. Cells were harvested by

centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 min at room temperature and

resuspended to an OD600 of 1.0 in buffered

methanol-complex medium (BMMY; 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 0.3%

K2HPO4, 1.18% KH2PO4,

1.34% YNB, 4×10−5% biotin, 0.5% methanol, pH 6.0). To

induce expression of rfowlicidin-2, methanol was added every 24 h

to a final concentration of 0.5% (v/v), after which the resuspended

culture was grown for 72 h and the supernatant was obtained by

centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The expression of

fowlicidin-2 in the supernatant was determined using Tricine-sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

(Tricine-SDS-PAGE). Total protein yield in the culture medium was

measured using a Bradford protein assay kit. The highest expressing

P. pastoris clone identified as P. pastoris X33-Fow2

was singled out and used for large-scale production of

rfowlicidin-2.

Purification of rfowlicidin-2

The fermentation medium obtained from the P.

pastoris X33-fowlicidin-2 fermentation was harvested by

centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. A total of 30 ml of

the resultant supernatant was loaded onto a Q-Sepharose Fast Flow

column (10 ml broth/5 ml resin; GE Healthcare Life Sciences,

Chalfont, UK) pre-equilibrated with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer

(pH 7.2; buffer A) for purification by ion exchange chromatography.

The column was washed again with buffer A, and then eluted with a

linear gradient of 0.0–1.0 M NaCl in buffer A. Fractions containing

fowlicidin-2 were collected and further purified by reversed phase

high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) on a C18 column

(250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; silica pore size, 300 Å; Supelco, Inc.,

Bellefonte, PA, USA), which had been pre-equilibrated using 0.1%

trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Bound proteins were eluted with a

linear gradient of acetonitrile (20–45%, v/v; 1.5% per min) in 0.1%

TFA. The flow rate was 1.0 ml/min and the absorbance of the eluent

was monitored at 214 nm. Purification was monitored by 15%

Tricine-SDS-PAGE. The purified peptide was lyophilized and stored

at −20°C until further analysis. The peptide yield was determined

using a Bradford protein assay kit.

Mass spectrometry and N-terminal

sequencing analysis

The purified peptide (30 ng) was dissolved in a

saturated solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid containing 50%

acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA, and then analyzed using a

Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight mass

spectrometer (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

For N-terminal sequencing analysis, the purified peptide was run on

a 15% tricine-SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and then transferred to a

polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (EMD Millipore,

Billerica, MA, USA) by semi-dry electrophoretic transfer.

N-terminal sequence analysis was performed by automated Edman

degradation using a PPSQ-33A Sequencing System (Shimadzu

Corporation, Kyoto, Japan), according to the manufacturer's

protocol.

Antibacterial activity assay

Antibacterial activity of fowlicidin-2 against

various microorganisms was tested using the microbroth dilution

method (16). Briefly, bacteria

subcultured in the log phase were diluted to

2×105-7×105 colony forming units/ml with

fresh Mueller Hinton Broth medium (Hopebio). Aliquots (50 µl) from

each strain suspension were distributed into the wells of a 96-well

polypropylene microtiter plate, after which 50 µl peptide was added

to each well. Cultures were grown for 18 h at 37°C with agitation.

The absorbance was measured at 600 nm using a microplate reader.

Experiments were performed in triplicate. The minimal inhibitory

concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest concentration of

peptide able to fully inhibit bacterial growth, as determined by OD

measurements.

Hemolytic activity assay

The hemolytic activity of rfowlicidin-2 was

determined using human red blood cells (hRBCs), as described

previously (17). Briefly, fresh

anticoagulated human blood from a healthy donor was washed thrice

with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and diluted to a concentration

of 4% (v/v) in PBS. The experimental protocol was reviewed and

approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital of NEAU. The

erythrocytes (90 µl) were dispensed into a 96-well plate, followed

by addition in triplicate of 10 µl serially diluted peptides. The

resulting suspension was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Following

centrifugation of the plate at 1,000 × g for 5 min at room

temperature, the supernatants were transferred to a new 96-well

plate and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA

plate reader for analysis of released hemoglobin. Negative controls

consisted of cells suspended in PBS only, and positive controls

consisted of cells suspended in 1% Triton X-100. The percentage of

hemolysis was calculated as follows: Percentage of hemolysis (%) =

[(A570 nm, peptide - A570 nm, PBS)/(A570

nm, 1% Triton X-100 - A 570 nm, PBS)] × 100.

Determination of anticancer activity

in vitro

The anticancer activity of rfowlicidin-2 was

determined using the

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

method, as described previously (18). Briefly, A375 human malignant melanoma

cells, RAW264.7 mice macrophages and CEFs were seeded into a

96-well plate at a density of 2.5×104 cells/well in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and cultured at 37°C in a

humidified 5% CO2 incubator. When the cell fusion

reached more than 80%, the cells were washed once with DMEM,

followed by the addition of 90 µl fresh DMEM containing 5% FBS and

various concentrations (0 to 128 µM) of 10 µl peptide in triplicate

into each well. Cells were incubated at 37°C for 24 h, after which

10 µl alamarBlue dye was added to each well and incubated for a

further 6 h. The fluorescence was measured at 490 nm. The

anticancer activity of rfowlicidin-2 was defined as the peptide

concentration that induced 50% cell death (EC50).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance

using SPSS version 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Differences among groups were compared with Student's t-test.

Results

Screening of positive

transformants

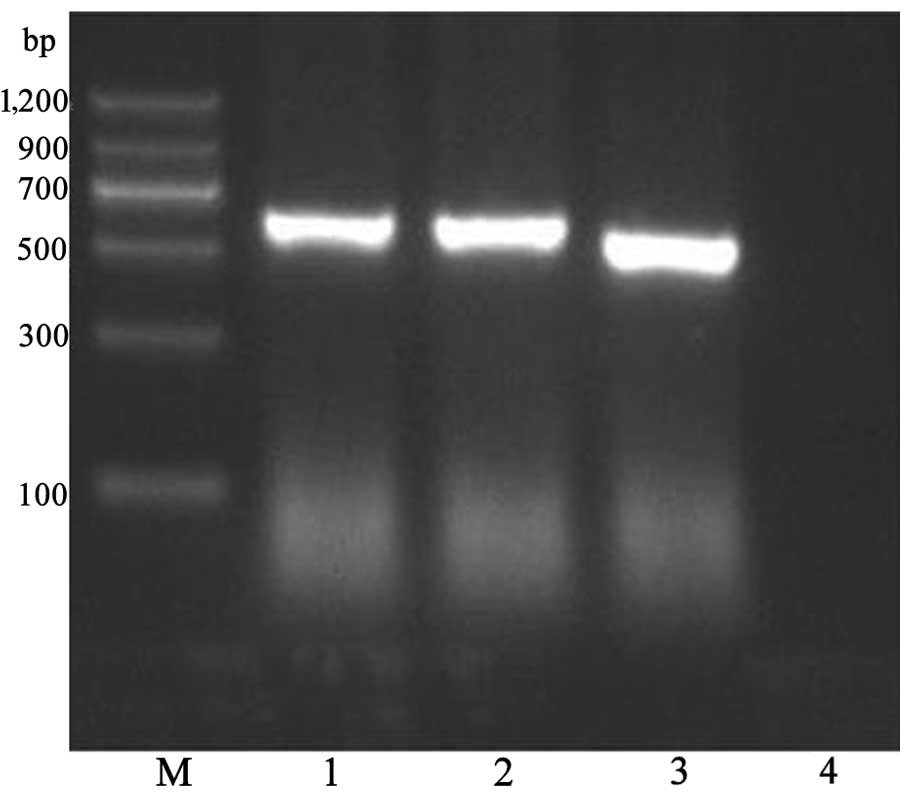

A fowlicidin-2 DNA fragment was inserted into the

EcoRI and XbaI sites of pPICZα-A to construct the

recombinant pPICZα-A-fowlicidin-2 vector. The pPICZα-A-fowlicidin-2

vector was transformed into P. pastoris X-33 cells by

electroporation, and the transformants that grew on MD plates were

identified by PCR (Fig. 2). A total

of 31 multicopy transformants were screened out on MD plates under

selection by Zeocin (100 µg/ml) and were confirmed by PCR

amplification. A total of 10 colonies presenting the

Zeocin+ Mut+ phenotype and with

strong PCR amplification products of fowlicidin-2 DNA were used for

the induced expression of the peptide.

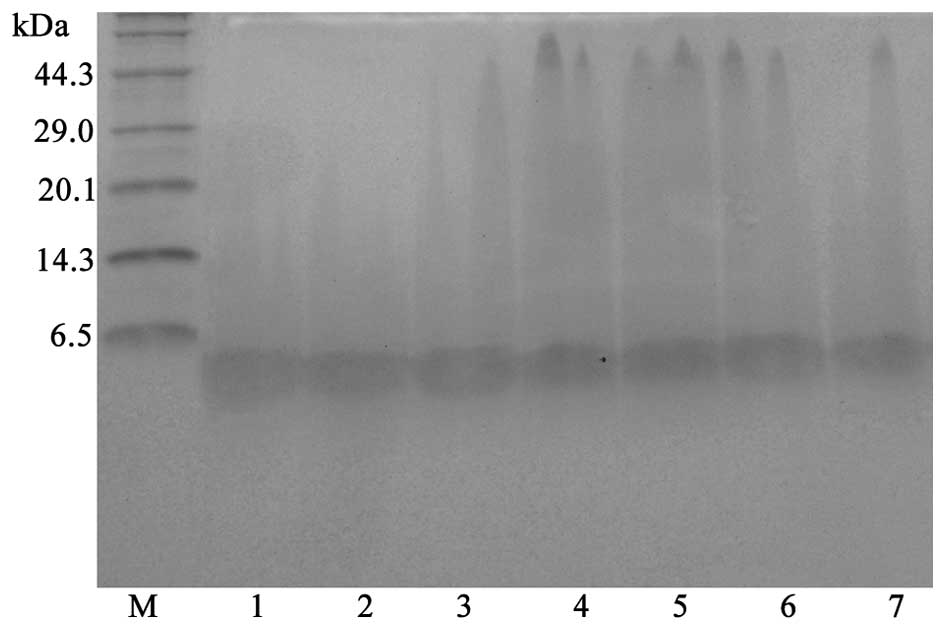

Expression of rfowlicidin-2

pPICZα-A-fowlicidin-2 transformants were analyzed

for the extracellular expression of fowlicidin-2 in BMMY broth at

28°C for 72 h. The highest-expressing transformant, P.

pastoris X33-Fow2, was selected for further high-density

cultivation. Aliquots of the culture supernatant were withdrawn at

12-h intervals and analyzed by Tricine-SDS-PAGE. As shown in

Fig. 3, a major protein band of ~3.7

kDa, which corresponded to fowlicidin-2, appeared following

induction with methanol. The highest expression level of

fowlicidin-2 was ~121 mg/l at 60 h of culture in the optimized

fermentation conditions (28°C, pH 6.0, 0.5% methanol in BMMY

medium).

Purification and identification of

rfowlicidin-2

After 60 h of methanol induction, the cultures were

harvested and the supernatants were collected for the purification

of rfowlicidin-2 using a Q-Sepharose Fast Flow column and RP-HPLC.

The highest peak absorbance fractions, which were pooled and

detected as a single band by Tricine-SDS-PAGE (Fig. 4), contained the majority of

rfowlicidin-2. The average volume of rfowlicidin-2 recovered from 1

liter culture medium was ~85.6 mg, with a purity of >95%. These

results indicate that rfowlicidin-2 may be successfully purified

from methylotrophic yeast, with a relatively high recovery rate and

purity, using a two-step purification strategy. The purified

rfowlicidin-2 was transferred to a PVDF membrane, and sequenced for

up to 4 cycles. The N-terminus began with a

leucine-valine-glutamine-arginine sequence, which was consistent

with the predicted sequence of rfowlicidin-2 (8). This indicates that the rfowlicidin-2

peptide that was produced did not have any additional amino acids

at its N-terminal end.

Antibacterial activity of

rfowlicidin-2

The MICs of the peptide for several microorganisms

are shown in Table I. Fowlicidin-2

showed strong and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activities against

both gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus ATCC 29213) and

gram-negative bacteria (E. coli 25922, P. aeruginosa

ATCC 27853, S. typhimurium C77-31). For these strains, the

MIC values were in the range of 1–4 µM.

| Table I.MICs of rfowlicidin-2 for four tested

bacteria. |

Table I.

MICs of rfowlicidin-2 for four tested

bacteria.

| Tested

bacteria | MIC (µM) |

|---|

| Escherichia

coli ATCC25922 | 1 |

| Staphylococcus

aureus ATCC29213 | 4 |

| Pseudomonas

aeruginosa ATCC27853 | 4 |

| Salmonella

typhimurium C77-31 | 2 |

Hemolytic activities of

rfowlicidin-2

To evaluate the hemolytic activity of fowlicidin-2

against red blood cells, fresh hRBCs were used. The peptide

exhibited a dose-dependent hemolytic activity against hRBCs, with

the EC50 occurring within the range of 128–256 µM

(Fig. 5).

Anticancer activity of

rfowlicidin-2

The cytotoxic activity of rfowlicidin-2 was assessed

against A375 human malignant melanoma cells, RAW264.7 mouse

macrophages and CEFs. Concentration-response studies demonstrated

that the peptide exerted a significantly higher cytotoxic activity

against the human malignant A375 cells (P<0.01), as compared

with the two other types of cells (Fig.

6). Fowlicidin-2 showed a 2-fold higher activity against the

human A375 cells (EC50=2–4 µM), as compared with the

RAW264.7 cells (EC50=4–8 µM), and an 8-fold higher

activity, as compared with the CEFs (EC50=16–32 µM;

Fig. 6).

Discussion

The emergence of pathogenic microorganisms with

resistance to conventional antibiotics has driven the search for

novel types of antimicrobial agents. Although numerous novel

strategies have been investigated, there are a number of avenues

that have yet to be explored (19).

AMPs are promising candidates for the development of novel

antimicrobial agents, since they have been shown to be an important

component of immunity and have a broad antimicrobial spectrum

(3). However, the production of

active AMPs in a cost-effective and scalable method is challenging.

It has been recognized that recombinant DNA techniques are a

potential means for producing AMPs in large quantities. Numerous

AMPs have been successfully produced using genetic engineering

methods (10). Various host cells

have been used for the expression of AMPs; however, P.

pastoris has emerged as one of the most efficient recombinant

bioreactors (20). Similar to

prokaryotes, P. pastoris is able to grow rapidly in

inexpensive medium, and is amenable to high-cell-density

fermentations (20,21). Furthermore, it is non-pathogenic and

is capable of secreting functional extracellular proteins directly

into the culture medium (21,22).

The present study used P. pastoris to express

fowlicidin-2 at a high level. The Kex2 recognition site was

introduced at the N-terminal of fowlicidin-2. The Kex2 endoprotease

is a member of the membrane-bound endoprotease family and is

responsible for site-specific endoproteolysis at pairs of basic

amino acid residues, in particular EKR, in the α-factor precursor

peptide (23,24). The translated peptide fowlicidin-2

was successfully released by Kex2, and was shown to have the

predicted amino acid sequence and molecular weight. Furthermore,

sequencing revealed that there were no additional residues at the

N-terminus of the peptide following Kex2 digestion, which was

important since the natural N-terminus is critical for the activity

of AMPs (25,26).

The antibacterial assay in the present study

indicates that rfowlicidin-2 is prominent among the most potent

cathelicidins discovered to date, showing activity against a

variety of bacteria at concentrations of ≤4 µM. In the present

study, the lowest detected MIC of rfowlicidin-2 was towards E.

coli 25922 (1 µM). The peptide exhibited a similar activity

against S. aureus ATCC29213 and P. aeruginosa

ATCC27853. These results demonstrate that the rfowlicidin-2 peptide

was functional and effective against gram-negative and

gram-positive bacteria. In addition, rfowlicidin-2 was shown to

exert a hemolytic effect on hRBCs, with EC50 occurring

at 128–256 µM, which is markedly higher than that reported by Xiao

et al (8). The underlying

mechanism is unclear and may be due to the different spatial

structures of the rfowlicidin-2 obtained in the present study and

the chemically synthesized fowlicidin-2 used in the study of Xiao

et al (8).

Several cationic amphipathic AMPs or their

derivatives have previously been reported to exert anticancer

activity, display selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells in

vitro and show efficacy in various in vivo xenograft

models (27,28). However, only a small range of AMPs

have been shown to have anticancer activity. Various

cathelicidin-related or cathelicidin-modified AMPs, including LL-37

(29), Ceragenin CSA-13 (30), FK-16 (31) and BF-30 (32), have been reported to exhibit

anticancer activity. However, to the best of our knowledge, there

have been no previous reports on the anticancer activity of

fowlicidin-2. Cationicity, α-helicity and amphipathicity are among

the most important physicochemical parameters that determine the

functional properties of α-helical AMPs (9,33).

Increasing the degree of α-helicity and mean hydrophobicity of AMPs

generally result in an increase in cytotoxicity against cancer

cells (34). The secondary structure

of fowlicidin-2 is dominated by α-helices. The N-terminal α-helix

of the peptide adopts a typical amphipathic structure, whereas the

C-terminal helix is more hydrophobic (9). In the present study, the anticancer

activity of fowlicidin-2 was determined using the MTT method in

vitro. The survival of cells was reduced by treatment with

fowlicidin-2, and the percentage of cell death increased in a

concentration-dependent manner. However, the EC50 of

fowlicidin-2 for A375 human cancer cells was 2–4 µM, and few A375

cells survived when treated with 8 µM fowlicidin-2. Conversely,

fowlicidin-2 showed relatively weak cytotoxic activity against

RAW264.7 cells (EC50=4–8 µM) and CEFs

(EC50=16–32 µM). These results suggested that

fowlicidin-2 may be considered a promising candidate for anticancer

applications. However, the mechanism of action of the peptide on

cancer cells requires further investigation.

In conclusion, in the present study bioactive

fowlicidin-2 was successfully expressed at a high level (85.6 mg/l)

and high purity (>95%) using the yeast P. pastoris as a

recombinant expression system. In addition, rfowlicidin-2 showed

strong and broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity and anticancer

activity. The present study was the first to demonstrate an

inhibitory effect of fowlicidin-2 on cancer cells in

vitro.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the Program for

Young Aged Academic Staff in the Heilongjiang Province Ordinary

College (grant no. 1252G010)U, the Research Fund for Innovation

Talents of Science and Technology in Harbin City (grant no.

2012RFQXN022) and the ‘Academic Backbone’ Project of Northeast

Agricultural University (grant no. 15XG15).

References

|

1

|

Rai J, Randhawa GK and Kaur M: Recent

advances in antibacterial drugs. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 3:3–10.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Spížek J, Novotná J, Rezanka T and Demain

AL: Do we need new antibiotics? The search for new targets and new

compounds. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 37:1241–1248. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zasloff M: Antimicrobial peptides of

multicellular organisms. Nature. 415:389–395. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hancock RE and Sahl HG: Antimicrobial and

host-defense peptides as new anti-infective therapeutic strategies.

Nat Biotechnol. 24:1551–1557. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tomasinsig L and Zanetti M: The

cathelicidins - structure, function and evolution. Curr Protein

Pept Sci. 6:23–34. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Zaiou M and Gallo RL: Cathelicidins,

essential gene-encoded mammalian antibiotics. J Mol Med (Berl).

80:549–561. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zaiou M, Nizet V and Gallo RL:

Antimicrobial and protease inhibitory functions of the human

cathelicidin (hCAP18/LL-37) prosequence. J Invest Dermatol.

120:810–816. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Xiao Y, Cai Y, Bommineni YR, Fernando SC,

Prakash O, Gilliland SE and Zhang G: Identification and functional

characterization of three chicken cathelicidins with potent

antimicrobial activity. J Biol Chem. 281:2858–2867. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Xiao Y, Herrera AI, Bommineni YR, Soulages

JL, Prakash O and Zhang G: The central kink region of fowlicidin-2,

an alpha-helical host defense peptide, is critically involved in

bacterial killing and endotoxin neutralization. J Innate Immun.

1:268–280. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Parachin NS, Mulder KC, Viana AA, Dias SC

and Franco OL: Expression systems for heterologous production of

antimicrobial peptides. Peptides. 38:446–456. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ahmad M, Hirz M, Pichler H and Schwab H:

Protein expression in Pichia pastoris: Recent achievements and

perspectives for heterologous protein production. Appl Microbiol

Biotechnol. 98:5301–5317. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gellissen G, Kunze G, Gaillardin C, Cregg

JM, Berardi E, Veenhuis M and van der Klei I: New yeast expression

platforms based on methylotrophic Hansenula polymorpha and Pichia

pastoris and on dimorphic Arxula adeninivorans and Yarrowia

lipolytica -A comparison. FEMS Yeast Res. 5:1079–1096. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Hélène B, Céline L, Patrick C, Fabien R,

Christine V, Yves C and Guy M: High-level secretory production of

recombinant porcine follicle-stimulating hormone by Pichia

pastoris. Process Biochem. 36:907–913. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Feng X, Xu W, Qu P, Li X, Xing L, Liu D,

Jiao J, Wang J, Li Z and Liu C: High-yield recombinant expression

of the chicken antimicrobial peptide fowlicidin-2 in Escherichia

coli. Biotechnol Prog. 31:369–374. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sambrook J, Fristsch EF and Maniatis T:

Molecular cloning: A laboratory manualSambrook J: Science Press;

Beijing: pp. 87–102. 2002, (In Chinese).

|

|

16

|

Chen Z, Wang D, Cong Y, Wang J, Zhu J,

Yang J, Hu Z, Hu X, Tan Y, Hu F and Rao X: Recombinant

antimicrobial peptide hPAB-β expressed in Pichia pastoris, a

potential agent active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

aureus. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 89:281–291. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Dean SN, Bishop BM and van Hoek ML:

Natural and synthetic cathelicidin peptides with anti-microbial and

anti-biofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol.

11:1142011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lin MC, Hui CF, Chen JY and Wu JL: The

antimicrobial peptide, shrimp anti-lipopolysaccharide factor

(SALF), inhibits proinflammatory cytokine expressions through the

MAPK and NF-κB pathways in Trichomonas vaginalis adherent to HeLa

cells. Peptides. 38:197–207. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Moellering RC Jr: New approaches to

developing antimicrobials for resistant bacteria. J Infect

Chemother. 9:8–11. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Jin F, Xu X, Zhang W and Gu D: Expression

and characterization of a housefly cecropin gene in the

methylotrophic yeast, Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr Purif.

49:39–46. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Cereghino JL and Cregg JM: Heterologous

protein expression in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris.

FEMS Microbiol Rev. 24:45–66. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang A, Wang S, Shen M, Chen F, Zou Z, Ran

X, Cheng T, Su Y and Wang J: High level expression and purification

of bioactive human alpha-defensin 5 mature peptide in Pichia

pastoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 84:877–884. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Fuller RS, Brake A and Thorner J: Yeast

prohormone processing enzyme (KEX2 gene product) is a

Ca2+-dependent serine protease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

86:1434–1438. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Seeboth PG and Heim J: In-vitro processing

of yeast alpha-factor leader fusion proteins using a soluble yscF

(Kex2) variant. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 35:771–776. 1991.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Li L, Wang JX, Zhao XF, Kang CJ, Liu N,

Xiang JH, Li FH, Sueda S and Kondo H: High level expression,

purification, and characterization of the shrimp antimicrobial

peptide, Ch-penaeidin, in Pichia pastoris. Protein Expr Purif.

392:144–151. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wu M and Hancock RE: Interaction of the

cyclic antimicrobial cationic peptide bactenecin with the outer and

cytoplasmic membrane. J Biol Chem. 274:29–35. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Huang W, Seo J, Willingham SB, Czyzewski

AM, Gonzalgo ML, Weissman IL and Barron AE: Learning from

host-defense peptides: Cationic, amphipathic peptoids with potent

anticancer activity. PLoS One. 9:e903972014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yang QZ, Wang C, Lang L, Zhou Y, Wang H

and Shang DJ: Design of potent, non-toxic anticancer peptides based

on the structure of the antimicrobial peptide, temporin-1CEa. Arch

Pharm Res. 36:1302–1310. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Büchau AS, Morizane S, Trowbridge J,

Schauber J, Kotol P, Bui JD and Gallo RL: The host defense peptide

cathelicidin is required for NK cell-mediated suppression of tumor

growth. J Immunol. 184:369–378. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Kuroda K, Fukuda T, Okumura K, Yoneyama H,

Isogai H, Savage PB and Isogai E: Ceragenin CSA-13 induces cell

cycle arrest and antiproliferative effects in wild-type and p53

null mutant HCT116 colon cancer cells. Anticancer Drugs.

24:826–834. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Ren SX, Shen J, Cheng AS, Lu L, Chan RL,

Li ZJ, Wang XJ, Wong CC, Zhang L, Ng SS, et al: FK-16 derived from

the anticancer peptide LL-37 induces caspase-independent apoptosis

and autophagic cell death in colon cancer cells. PLoS One.

8:e636412013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang H, Ke M, Tian Y, Wang J, Li B, Wang

Y, Dou J and Zhou C: BF-30 selectively inhibits melanoma cell

proliferation via cytoplasmic membrane permeabilization and

DNA-binding in vitro and in B16F10-bearing mice. Eur J Pharmacol.

707:1–10. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Conlon JM, Mechkarska M, Prajeep M, Arafat

K, Zaric M, Lukic ML and Attoub S: Transformation of the naturally

occurring frog skin peptide, alyteserin-2a into a potent, non-toxic

anti-cancer agent. Amino Acids. 44:715–723. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Gaspar D, Veiga AS and Castanho MA: From

antimicrobial to anticancer peptides. A review. Front Microbiol.

4:2942013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|