Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a major global health

concern. The main goal of CHB treatment is to reduce the risk of

chronic liver disease and related complications and improve the

quality of life and survival (1).

Guidelines for the management of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection

indicate that hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) loss is a key

endpoint of interest and is strongly recommended (2). Currently, there are two main

treatment options for CHB: treatment with a nucleos(t)ide analog

(NA) or pegylated interferon α-2a (Peg-IFN).

Antiviral therapy aimed at reducing HBV DNA levels

to the extent possible is important in the management of CHB, and

NA renders HBV DNA undetectable in most patients with CHB. However,

HBsAg clearance is unlikely to occur during a patient's lifetime,

even if HBV replication is well-controlled (3,4).

Peg-IFN is known to enhance innate immunity by preventing HBV

protein formation and depleting the covalently closed circular DNA

(cccDNA) pool in the liver (5-7).

Therefore, PEG-IFN therapy may result in greater HBsAg reduction

than NA therapy (8).

In previous studies, Peg-IFN add-on therapy to NA

was reported to be superior to monotherapy in terms of promoting

HBeAg loss and HBsAg reduction in patients with HBeAg-positive CHB

(9,10). Regarding the impact of HBsAg

levels, there are few studies with short-term follow-up after the

end of treatment in HBeAg-negative CHB patients who received

Peg-IFN in addition to NA; however, there are no reports of

long-term follow-up. Moreover, the conditions under which HBsAg

levels are further reduced in patients are not well understood.

The purpose of this study is to investigate the

conditions under which Peg-IFN is effective by observing changes in

HBsAg levels during and one year after Peg-IFN administration in

HBeAg negative patients who received NA treatment and remained HBV

DNA negative.

Patients and methods

Patients

This study included 17 patients with CHB who began

Peg-IFN therapy at the Department of Gastroenterology and

Neurology, Kagawa University Hospital, Japan, between September

2013 and April 2021. All patients were serum HBsAg-positive,

HBsAb-negative, HBeAg-negative and HBeAb-positive. They had

received NA therapy for more than 1 year, and their HBV DNA levels

were below detection sensitivity. The patients had no history of

interferon (IFN) treatment. All patients had hepatitis B and were

free of other viruses, such as the hepatitis C virus or autoimmune

hepatitis. None of the patients had a history of drug abuse or

alcoholic hepatitis. The exclusion criteria were neutrophil count

<1,500/mm3, platelet count <90,000/mm3,

hemoglobin concentration <10 g/dl, cirrhosis, history of organ

transplantation, and other known diseases for which Peg-IFN therapy

was not suitable. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee

of Kagawa University Hospital on June 20, 2019 (approval no.

2019032). An oral informed consent was obtained from all the

participants. Written informed consent was not required by the

ethics committee because the data involved routinely collected

medical data. All data were obtained from patient medical

records.

Peg-IFN therapy

Patients received subcutaneous injections of Peg-IFN

α-2a (PEGASYS: Hoffmann-La Roche Inc., Basel, Switzerland) at 180

µg per week for 48 weeks. The dose of Peg-IFN was modified for

adverse events according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The

patients were followed up monthly for 12 months after treatment

completion.

Laboratory tests

Virological and biochemical assessments were

performed monthly and follow-up data were collected. HBsAg levels

were measured using ARCHITECT i2000 (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago,

IL, USA). HBV genotypes were determined using enzyme immunoassays.

HBV DNA levels were measured using a Cobas®TaqMan®48 analyzer

(Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA). Blood HBV DNA

measurements were performed using the COBAS TaqMan HBV Test, v 2.0

(Roche Diagnostics K.K, Tokyo, Japan) (~2018/6) and the COBAS

6800/8800 HBV System (Roche Diagnostics K.K) (2018/7~) was used for

this study, which is based on a polymerase reaction assay. HBV DNA

values >1.3 log IU/ml were considered positive.

Assessment of effectiveness

In this study, responders were defined as those with

a 50% or greater decrease in HBsAg levels from baseline at week 96.

Conversely, non-responders were defined as those with a decrease in

HBsAg levels of less than 50% from baseline at week 96.

Statistical analysis

Data on baseline characteristics are presented as

median values. Patient characteristics were compared using unpaired

Student's t-test. Fisher's exact tests were used to analyze

categorical variables in both groups. Repeated measures ANOVA and

the Tukey's test was performed to analyze the changes in serum

HBsAg levels from baseline at weeks 0, 48 and 96. The mean value

indicates a change in the amount of HBsAg. The results were

considered significant at P<0.05. All statistical calculations

were performed using the JMP software (version 15, SAS Institute,

USA).

Ethical approval statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Kagawa University Hospital (approval no. 2019032). Oral informed

consent was obtained from all participants. The ethics committee

waived written informed consent because the data were collected

routinely in medical practice. Information was removed from the

data prior to analysis, and all methods were performed in

accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The patients' baseline characteristics are

summarized in Table I.

| Table IClinical and demographic

characteristics of patients at the start of Peg-IFN treatment. |

Table I

Clinical and demographic

characteristics of patients at the start of Peg-IFN treatment.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Sex, male/female | 12/5 |

| Age, years | 55.5 (41.6-69.9) |

| Genotype,

B/C/unknown | 1/11/5 |

| HBsAg titer,

lU/ml | 475 (4-19,049) |

| AST, IU/l | 22 (18-43) |

| ALT, IU/l | 23 (11-62) |

| Albumin, g/dl | 4.4 (4.0-4.8) |

| Total bilirubin,

mg/dl | 0.8 (0.3-2.8) |

| Platelet,

x103/µl | 16.6 (8.4-45.7) |

| PT, % | 85 (70-129) |

| Fib-4 index | 0.8 (0.6-3.9) |

| NA use start age,

years | 51.2 (35.1-63.8) |

| NA use period until

Peg-IFN treatment starts, years | 4.8 (1.0-13.5) |

HBsAg response

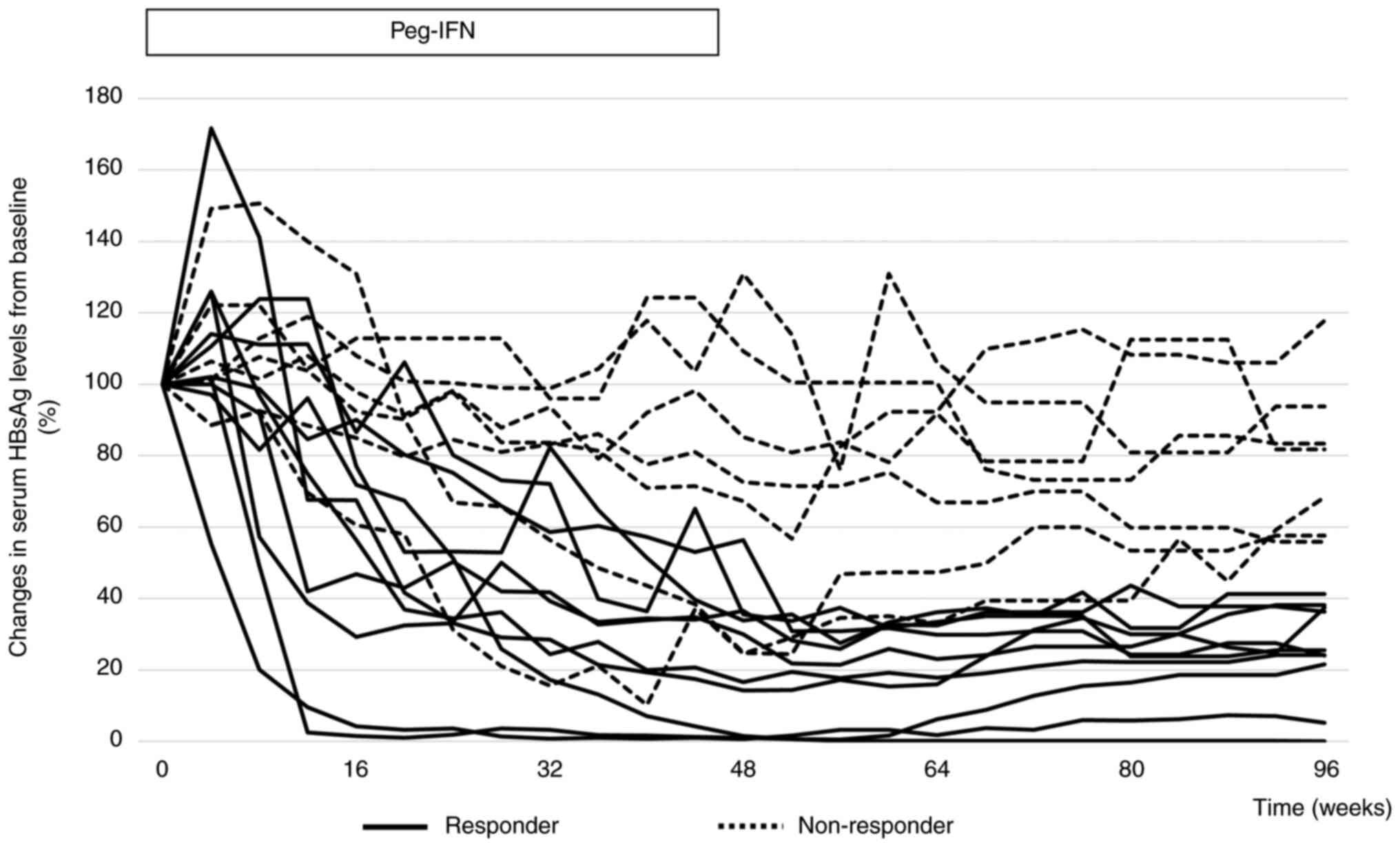

The clinical course of HBsAg in all patients is

shown in Fig. 1. In 10 of the 17

patients (58.8%), HBsAg levels decreased by more than 50% from

baseline at week 96. No patient achieved HBsAg clearance. In two

patients, HBsAg levels were higher at week 48 than at baseline.

However, in these two cases, HBsAg levels decreased from baseline

at week 96. In only one case, the HBsAg level increased at week 96

compared to that at baseline. In 9 of the 17 patients (52.9%),

HBsAg levels were higher at week 96 than at week 48.

Fig. 2 shows the

mean HBsAg levels at weeks 48 and 96 compared to baseline. In all

groups, HBsAg levels were 43.5 and 47.7% at weeks 48 and 96,

respectively (Fig. 2A). In the

responder group, the percentages were 22.6 and 25.3% at weeks 48

and 96 weeks, respectively (Fig.

2B). In the non-responder group, the percentages were 73.5 and

79.7% at 48 and 96 weeks, respectively (Fig. 2C). In the responder group, there

was a significant decrease in HBsAg levels at week 48 compared with

baseline, but not in the non-responder group. All groups showed a

significant decrease in HBsAg levels at week 96 compared to

baseline. All groups showed an increase in HBsAg levels at week 96

compared to week 48, but the difference was not significant.

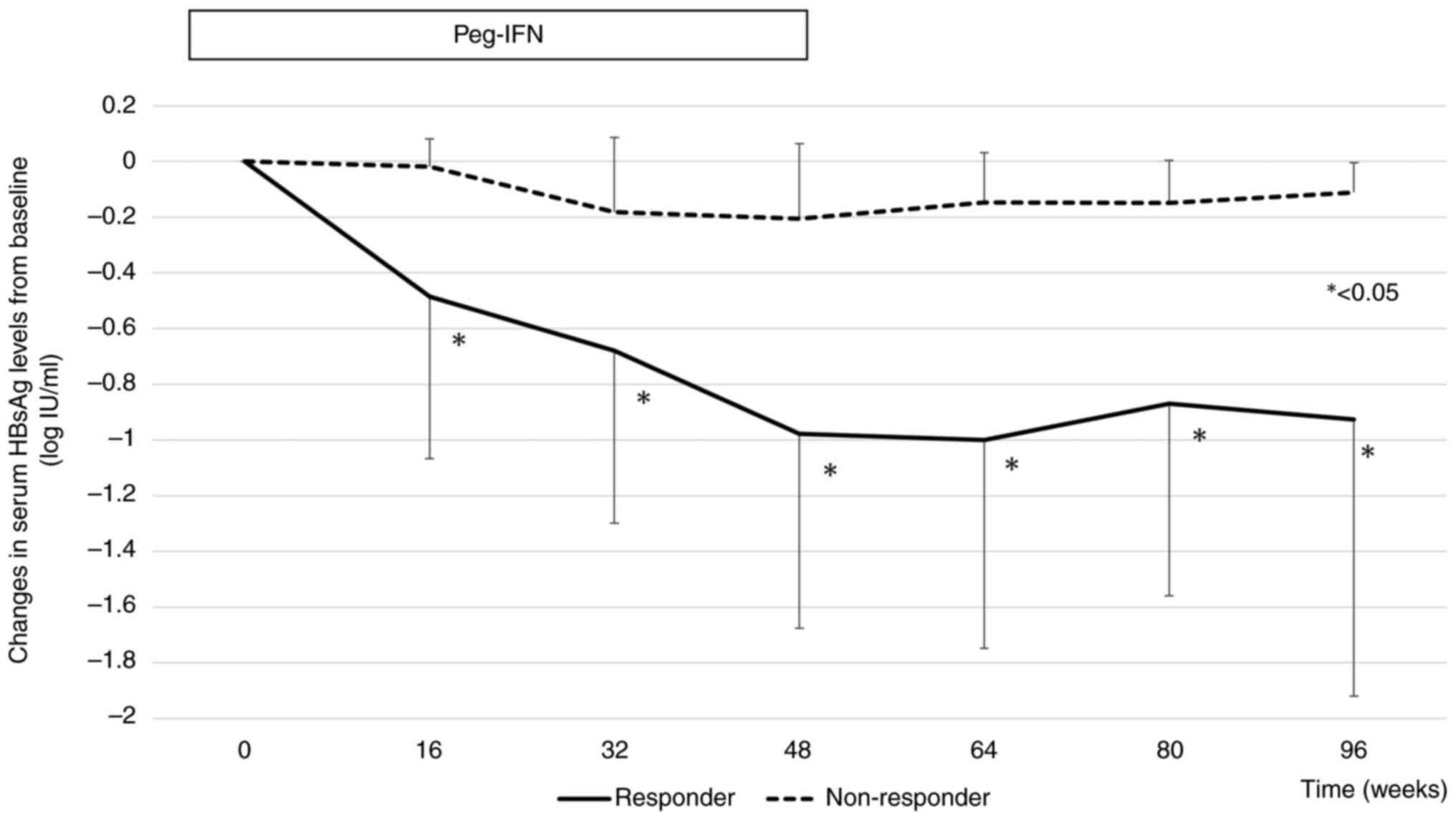

Changes in serum HBsAg levels from baseline in the

responder and non-responder groups are shown in Fig. 3. The mean declines in HBsAg levels

from baseline were -0.97, and -0.92 log IU/ml at weeks 48 and 96,

respectively, in the responder group, and -0.20, and -0.11 log

IU/ml at weeks 48 and 96, respectively, in the non-responder group.

From week 16 of Peg-IFN therapy, there was a significant difference

in the decrease in HBsAg levels from baseline between responders

and non-responders.

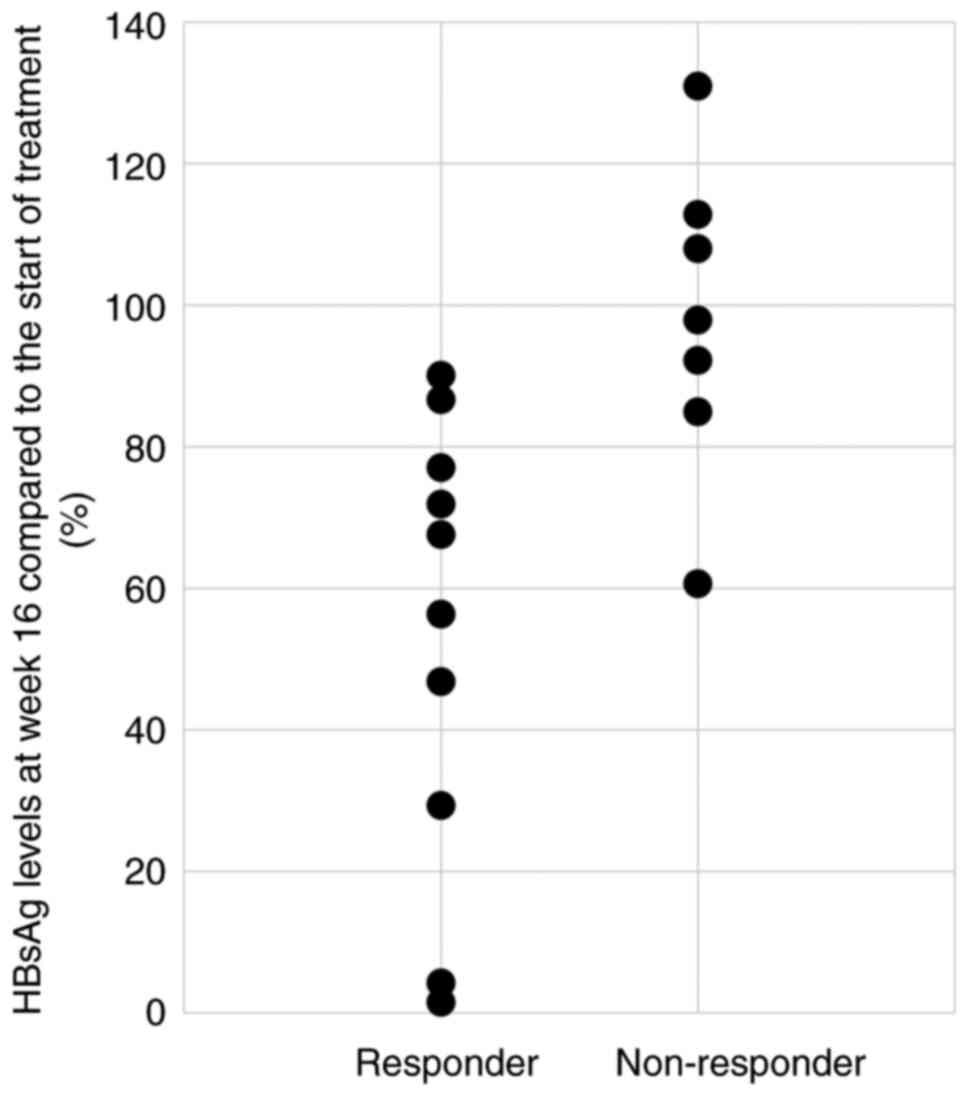

Fig. 4 shows the

HBsAg levels at week 16 compared to baseline for each case in the

responder and non-responder groups. In the responder group, 5

patients (50%) had a decrease in HBsAg level to 60% or less at week

16 compared to baseline. Conversely, there were no cases in the

non-responder group in which the HBsAg levels decreased below 60%.

The Fisher's exact test showed a significant difference between the

responding and non-responding groups in terms of whether HBsAg

levels reached 60% or less at week 16 compared to baseline

(Table II).

| Table IIHBsAg levels from baseline. |

Table II

HBsAg levels from baseline.

| Group | HBsAg ≥60% | HBsAg <60% | P-value |

|---|

| Responder (n) | 5 | 5 | <0.05 |

| Non-responder

(n) | 7 | 0 | |

Contributing factors for prediction of

responders

A comparison of pretreatment factors between

responders and non-responders is presented in Table III. In the univariate analysis,

age at the start of NA use and the duration of NA use until the

start of treatment were significant pre-treatment factors

associated with HBsAg response.

| Table IIIComparison of pre-treatment clinical

and demographic characteristics between the HBsAg responder and

non-responder groups. |

Table III

Comparison of pre-treatment clinical

and demographic characteristics between the HBsAg responder and

non-responder groups.

| Factors | Responder (n=10) | Non-responder

(n=7) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex, male/female | 8/2 | 4/3 | 0.314 |

| Age, years | 49.5 (41.6-69.9) | 57.0 (52.0-67.0) | 0.181 |

| Genotype,

B/C/unknown | 0/6/3 | 1/5/2 | 0.190 |

| HBsAg titer,

IU/ml | 433 (132-19,049) | 726 (4-3,473) | 0.575 |

| AST, IU/l | 21 (19-37) | 23 (18-43) | 0.428 |

| ALT, IU/l | 18 (13-62) | 23 (11-43) | 0.775 |

| Albumin, g/dl | 4.4 (4.0-4.8) | 4.4 (4.1-4.7) | 0.306 |

| Total bilirubin,

mg/dl | 0.9 (0.3-1.6) | 0.7 (0.4-2.8) | 0.916 |

| Platelet,

x103/µl | 18.0 (8.4-25.9) | 16.4 (10.9-45.7) | 0.414 |

| PT, % | 85 (70-98) | 96 (78-129) | 0.150 |

| Fib-4 index | 1.8 (0.8-2.8) | 1.5 (0.6-3.9) | 0.699 |

| NA use start age,

years | 45.4

(35.1-61.1) | 55.7

(47.2-63.8) | 0.025 |

| NA use period until

Peg-IFN treatment starts, years | 7.3 (3.0-13.5) | 1.5 (1.0-6.1) | 0.004 |

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the effect of adding

Peg-IFN to NA on HBsAg reduction in HBeAg-negative patients whose

serum HBV DNA was undetectable after NA treatment. From a clinical

perspective, predicting whether a patient can achieve HBsAg

clearance before initiating Peg-IFN therapy is important. After 48

weeks of Peg-IFN therapy, the group whose HBsAg level was 50% of

the level before initiation and after 48 weeks of observation (week

96) was defined as the responder group and was compared with the

non-responder group.

Previous studies on a larger group of patients

reported that Peg-IFN treatment was effective as long as the

patient was in the immune reaction phase, regardless of whether the

patient was HBeAg positive or negative (11,12).

However, to our knowledge, the first study was on the

administration of Peg-IFN in HBeAg-positive cases (11). The second study had a design in

which patients who became HBeAg-negative with NAs were administered

Peg-IFN in combination for several weeks, and then Peg-IFN was

administered alone (12). Our

study differs from theirs in that we limited our subjects to

HBeAg-negative and HBeAb-positive cases and did not discontinue NA

even after starting Peg-IFN therapy. Our study is the first report

in this regard.

Although NAs strongly suppress HBV DNA, a large

multicenter long-term NAs therapy cohort study showed a 10-year

HBsAg loss rate of 2.1% and an annual incidence rate of only 0.22%

with little hope of HBsAg seroclearance (13). According to a study by

Papatheodoridis et al, HBsAg levels decreased by a median of

0.13 and 0.17 log IU/ml at 48 and 96 weeks, respectively, compared

to baseline, in HBeAg-negative CHB patients administered NA

monotherapy (14). The present

study did not directly compare the HBsAg reduction rate between NA

monotherapy and Peg-IFN and NA combination therapy. This is a

potential limitation of this study. However, it seems that the

addition of Peg-IFN to NA does not reduce HBsAg compared to NA

monotherapy because the rate of decrease in HBsAg levels is 0.20

log IU/ml and 0.11 log IU/ml at 48 and 96 weeks, respectively, in

non-responders. However, in the response group, the decrease in the

amount of HBsAg from the baseline was 0.97 log IU/ml at 48 weeks

and 0.92 log IU/ml at 96 weeks, which was remarkable. From this

perspective, it seems worthwhile to consider targeting and

administering Peg-IFN to patients who are expected to respond to

it.

NAs have been demonstrated to suppress liver

fibrosis and reduce the incidence of HCC (15-17).

To obtain such effects, it is necessary to use NAs continuously for

long periods, which may cause adherence and compliance problems.

Additionally, patients from resource-limited countries or regions

cannot afford the financial burden of long-term NAs therapy

(18). Our study showed that the

highest rate of HBsAg reduction was observed in patients who were

younger when NA therapy was initiated, and had a longer history of

NAs use. Based on this result, young patients taking NAs may also

consider Peg-IFN combination therapy with the goal of achieving

early seroclearance of HBsAg. Better use of different combinations

of antiviral drugs could make the treatment more cost-effective and

drug-free.

At week 16, a significant difference was observed

between the responding and non-responding groups in terms of the

rate of decrease in HBsAg levels. If the HBsAg level at week 16 was

<60% of that at the start of Peg-IFN therapy, the response to

Peg-IFN therapy was considered good. Based on these results, it may

be necessary to observe the rate of decrease in HBsAg levels at

week 16 and to consider continuing Peg-IFN as an add-on

therapy.

While some studies have shown that pretreatment

HBsAg titer is an important factor associated with the outcome of

HBsAg loss in Peg-IFN therapy (19,20),

long-term observational studies have reported that early serum

HBsAg decline is highly predictive of HBsAg serum clearance

(21-24).

In a previous study, we reported that HBsAg titers <120 IU/ml

may achieve HBsAg clearance with Peg-IFN monotherapy (25). In contrast, this study showed that

when Peg-IFN was added to NA, there was no significant difference

in the HBsAg levels between responders and non-responders at the

start of treatment. In the current study, we focused on

HBeAg-negative and HBeAb-positive patients; therefore, it is

possible that the baseline HBsAg level was not high, and the small

number of cases led to different results.

Although IFN-α therapy has a limited treatment

period, it has the advantage of lasting effects even after

treatment (26). In this study, we

defined the responder and non-responder groups based on the HBsAg

level at 1-year follow-up (week 96); however, we believe that

extending the observation period will deepen our understanding of

the therapeutic effects.

This study has certain limitations, the most

important of which is its retrospective design. This increases the

probability that the treatment assignment is subject to selection

bias. The study required weekly hospital visits for Peg-IFN

administration for 48 weeks and was limited to patients with time

and financial resources. It is also possible that a selection bias

may have been at work that excluded older individuals from the

study, as they may not have benefited sufficiently from

participation given their prognosis. In addition, the sample size

was relatively small. This raises questions regarding whether the

results can be generalized. Larger prospective studies are required

to confirm and extend the results of this study.

In conclusion, in HBeAg-negative patients with CHB,

the addition of Peg-IFN to NA therapy can further reduce the amount

of HBsAg in a population that is younger when NA is initiated and

undergoes NA therapy for a prolonged duration. In addition, a

decrease in HBsAg below 60% of the pre-start level at week 16 after

the start of Peg-IFN therapy could be a marker for predicting

efficacy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

SM, MO, TH and TM contributed to the study

conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed

by SM, KF, KT, MN, KO, TT, JT and AM. The first draft of the

manuscript was written by SM and TM. SM and KF confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors commented on previous

versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Kagawa University Hospital (approval no. 2019032). Oral informed

consent was obtained from all the participants. Written informed

consent was not required by the ethics committee because the data

involved routinely collected medical data.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wigfield P, Sbarigia U, Hashim M, Vincken

T and Heeg B: Are published health economic models for chronic

hepatitis B appropriately capturing the benefits of HBsAg Loss? A

systematic literature review. Pharmacoecon Open. 4:403–418.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Sarin SK, Choudhury A, Sharma MK, Maiwall

R, Al Mahtab M, Rahman S, Saigal S, Saraf N, Soin AS, Devarbhavi H,

et al: Acute-on-chronic liver failure: Consensus recommendations of

the Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver (APASL):

An update. Hepatol Int. 13:353–390. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chevaliez S, Hézode C, Bahrami S, Grare M

and Pawlotsky JM: Long-term hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

kinetics during nucleoside/nucleotide analogue therapy: Finite

treatment duration unlikely. J Hepatol. 58:676–683. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zoutendijk R, Hansen BE, Van Vuuren AJ,

Boucher CA and Janssen HL: Serum HBsAg decline during long-term

potent nucleos(t)ide analogue therapy for chronic hepatitis B and

prediction of HBsAg loss. J Infect Dis. 204:415–418.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Boni C, Penna A, Bertoletti A, Lamonaca V,

Rapti I, Missale G, Pilli M, Urbani S, Cavalli A, Cerioni S, et al:

Transient restoration of anti-viral T cell responses induced by

lamivudine therapy in chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 39:595–605.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Tjwa ET, Van Oord GW, Hegmans JP, Janssen

HL and Woltman AM: Viral load reduction improves activation and

function of natural killer cells in patients with chronic hepatitis

B. J Hepatol. 54:209–218. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Swiecki M and Colonna M: Type I

interferons: Diversity of sources, production pathways and effects

on immune responses. Curr Opin Virol. 1:463–475. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wursthorn K, Lutgehetmann M, Dandri M,

Volz T, Buggisch P, Zollner B, Longerich T, Schirmacher P, Metzler

F, Zankel M, et al: Peginterferon alpha-2b plus adefovir induce

strong cccDNA decline and HBsAg reduction in patients with chronic

hepatitis B. Hepatology. 44:675–684. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Brouwer WP, Xie Q, Sonneveld MJ, Zhang N,

Zhang Q, Tabak F, Streinu-Cercel A, Wang JY, Idilman R, Reesink HW,

et al: Adding pegylated interferon to entecavir for hepatitis B e

antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B: A multicenter randomized

trial (ARES study). Hepatology. 61:1512–1522. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Li GJ, Yu YQ, Chen SL, Fan P, Shao LY,

Chen JZ, Li CS, Yi B, Chen WC, Xie SY, et al: Sequential

combination therapy with pegylated interferon leads to loss of

hepatitis B surface antigen and Hepatitis B e Antigen (HBeAg)

seroconversion in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients

receiving long-term entecavir treatment. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother. 59:4121–4128. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Brouwer WP, Chan HLY, Lampertico P, Hou J,

Tangkijvanich P, Reesink HW, Zhang W, Zhang W, Mangia A, Tanwandee

T, et al: Genome-wide association study identifies genetic variants

associated with early and sustained response to (Pegylated)

interferon in chronic hepatitis B patients: The GIANT-B study. Clin

Infect Dis. 69:1969–1979. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Hu P, Shang J, Zhang W, Gong G, Li Y, Chen

X, Jiang J, Xie Q, Dou X, Sun Y, et al: HBsAg Loss with

Peg-interferon Alfa-2a in Hepatitis B patients with partial

response to nucleos(t)ide Analog: New switch study. J Clin Transl

Hepatol. 6:25–34. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Hsu YC, Yeh ML, Wong GL, Chen CH, Peng CY,

Buti M, Enomoto M, Xie Q, Trinh H, Preda C, et al: Incidences and

determinants of functional cure during entecavir or tenofovir

disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B. J Infect Dis.

224:1890–1899. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Papatheodoridis G, Goulis J,

Manolakopoulos S, Margariti A, Exarchos X, Kokkonis G, Hadziyiannis

E, Papaioannou C, Manesis E, Pectasides D and Akriviadis E: Changes

of HBsAg and interferon-inducible protein 10 serum levels in naive

HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients under 4-year entecavir

therapy. J Hepatol. 60:62–68. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ,

Pokornowski KA, Eggers BJ, Fang J, Wichroski MJ, Xu D, Yang J,

Wilber RB and Colonno RJ: Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis b

virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare

through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 49:1503–1514.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chang TT, Liaw YF, Wu SS, Schiff E, Han

KH, Lai CL, Safadi R, Lee SS, Halota W, Goodman Z, et al: Long-term

entecavir therapy results in the reversal of fibrosis/cirrhosis and

continued histological improvement in patients with chronic

hepatitis B. Hepatology. 52:886–893. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yang SC, Lee CM, Hu TH, Wang JH, Lu SN,

Hung CH, Changchien CS and Chen CH: Virological response to

entecavir reduces the risk of liver disease progression in

nucleos(t)ide analogue-experienced HBV-infected patients with prior

resistant mutants. J Antimicrob Chemother. 68:2154–2163.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Liaw YF: Antiviral therapy of chronic

hepatitis B: Opportunities and challenges in Asia. J Hepatol.

51:403–410. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wu FP, Yang Y, Li M, Liu YX, Li YP, Wang

WJ, Shi JJ, Zhang X, Jia XL and Dang SS: Add-on pegylated

interferon augments hepatitis B surface antigen clearance vs

continuous nucleos(t)ide analog monotherapy in Chinese patients

with chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis B surface antigen ≤ 1500

IU/mL: An observational study. World J Gastroenterol. 26:1525–1539.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yoshida K, Enomoto M, Tamori A, Nishiguchi

S and Kawada N: Combination of entecavir or tenofovir with

pegylated interferon-α for long-term reduction in hepatitis B

surface antigen levels: Simultaneous, sequential, or add-on

combination therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22: 1456, 2021.

|

|

21

|

Brunetto MR, Moriconi F, Bonino F, Lau GK,

Farci P, Yurdaydin C, Piratvisuth T, Luo K, Wang Y, Hadziyannis S,

et al: Hepatitis B virus surface antigen levels: A guide to

sustained response to peginterferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative

chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 49:1141–1150. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Moucari R, Mackiewicz V, Lada O, Ripault

MP, Castelnau C, Martinot-Peignoux M, Dauvergne A, Asselah T, Boyer

N, Bedossa P, et al: Early serum HBsAg drop: A strong predictor of

sustained virological response to pegylated interferon alfa-2a in

HBeAg-negative patients. Hepatology. 49:1151–1157. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Rijckborst V, Hansen BE, Cakaloglu Y,

Ferenci P, Tabak F, Akdogan M, Simon K, Akarca US, Flisiak R,

Verhey E, et al: Early on-treatment prediction of response to

peginterferon alfa-2a for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B using

HBsAg and HBV DNA levels. Hepatology. 52:454–461. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Boglione L, Cusato J, Cariti G, Di Perri G

and D'Avolio A: Role of HBsAg decline in patients with chronic

hepatitis B HBeAg-negative and E genotype treated with

pegylated-interferon. Antiviral Res. 136:32–36. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Mimura S, Fujita K, Takuma K, Nakahara M,

Oura K, Tadokoro T, Kobara H, Tani J, Morishita A, Himoto T and

Masaki T: Effect of pegylated interferon alfa-2a in HBeAg-negative

chronic hepatitis B during and 48 weeks after off-treatment

follow-up: the limitation of pre-treatment HBsAg load for the

seroclearance of HBsAg. Intern Emerg Med. 16:1559–1565.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Brunetto MR and Bonino F: Interferon

therapy of chronic hepatitis B. Intervirology. 57:163–170.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|