1. Introduction

As reported from the Hellenic Classical Era,

hematidrosis is a rare medical cutaneous condition (International

Classification of Diseases/ICD-10: L 74.8) which has rarely been

noted throughout the ages. It is regarded as an eccrine sweat

disorder, which is defined as the spontaneous dermatological

excretion of a mixture of blood and sweat directly from

non-traumatized skin. The pathological mechanism of blood oozing

from the skin and mucosa remains unclear. However, it is

hypothesized that dermal deficiencies can lead to blood-filled

spaces, which may be exuded into follicular canals, or directly to

the skin surface, demonstrating this peculiar phenomenon (1,2). As

a medical term, it is composed of two Greek words ‘hema’ (blood)

and ‘idrosis’ (sweating), while certain other associated terms used

in the English medical literature include the words stigmata (also

of Greek origin, hysterical stigmata), diapedesis (also of Greek

origin, meaning jumping through), vicarious menstruation,

ephidrosis cruenta (Greco-Latin origin), sudor cruentus and sudor

sanguineus (Latin terms) (3).

Hematidrosis, is classed as a somatic symptom disorder, almost

always related to psychic imbalance, ranging from acute or chronic

anxiety to fear (rivalry, scolding, punishment, bullying). Reports

exist of extensive unnecessary investigations, which at times, have

led towards risky therapeutic interventions (1,2,4).

Thomas K. Chambers in 1861, suggested that this strange experience

had triggered a ‘need to publish’ trend of case reports that

otherwise may have been neglected. Nevertheless, the majority of

available articles on the subject have appeared over the past

decades. In Christianity, its notorious appearance was connected to

the agony in the biblical historical reference on the ‘bloody

tears’ of Jesus Christ in the Garden of Gethsemane (1,5).

The present study, inspired by the nature of

hematidrosis itself, aimed to highlight both the hallmarks in the

history of medicine, as well as the currently available scientific

evidence. By searching through the archives of the literature in

the past and simultaneously conducting a narrative review of the

recent research, the present study aimed to provide a clearer

picture and a thesaurus for this ‘marvel’ entity in

dermatology.

2. Literature search strategy

A research strategy was developed to identify

relevant literature. This included selecting key search terms and

deciding on the criteria of inclusion and exclusion. Moreover,

certain conditions were set that are critical to the quality and

breadth of the present scoping review, framed by historical and

epistemological sources, starting from their compatibility and

retrospective consistency in the clinical context. The Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA)

guidelines were used consultatively to avoid a major quality

deficit regarding the studies included (6). The key words which were used to

render and describe this clinical entity were verbally similar

diagnostic terms concerning their syllabic pronunciation to provide

access to appropriate articles, chapters and books and various

references, thus explaining the intended dual search. Key words

included hemaditrosis, haematidrosis, hemathidrosis, αίµα and

ιδρώτας (blood and sweat for the Greek texts), diapedesis, stigmata

hysterica, sudor cruentus and sudor sanguineus (bleeding sweat and

bloody sweat for the Latin texts). All terms are considered

directly related to the research question. The present narrative

review was based on original studies, clinical case reports and

series, opinion articles, letters to the editor and review articles

to investigate recent knowledge. A thorough survey was conducted in

the online medical database PubMed/Medline for studies published

over the past two decades until December 1, 2022. To limit the

search and to set criteria, full-text articles published in the

English language were only included. The eligibility of each

citation was based on the title, abstract and full content of the

articles considered and retrieved, taking into account the

predefined admission criteria, such as methodological excellence,

authorship, the relevance of the responsible correspondence author,

and the quality and visibility characteristics of the biomedical

journal hosting the publication. The factors that were evaluated

covered the frequency of recording the clinical entity, management

parameters, the time course of clinical manifestations, coexisting

pathologic conditions and the socio-demographic and clinical

characteristics of the patients. For the historical investigation,

a bibliographic review was conducted using a documentary research

methodology, applying the same key words as aforementioned. The

year 1900 marked the end of the historical research. The survey

included the following: i) Texts of antiquity within the online

database Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG) in Latin and Greek

language; ii) works within Gallica Digital Library (Gallica-BnF) in

the French language; and iii) books within online Google Digital

Book Index (Google Books) in the English, French, German, Italian

and Latin languages. Full-text availability was set as a criterion.

Cases associated with religion and religious books were excluded

for possible bigotry and deisidaimonía (superstition) to be

avoided. On the other hand, this exclusion criterion may provoke a

bias concerning cases with true hematidrosis. Thus, cases

presenting hematidrosis during stigmata phenomenon were excluded

from the main review; however, as they were partly connected to the

symptom in study, they are being historically perused, discussed

and registered independently.

3. Results of the literature search

Historical records unveiled relevant fragments of

treatises during Greek antiquity, the case of Jesus Christ in early

Christianity and 64 works with case references from the Renaissance

until 1900. A summary of nine works had been included from within

TLG, seven from Gallica-BnF and 57 form Google Books. Of the cases

referred, 29 were in English, 13 in French, 13 in Latin, eight in

German and one in Italian. Among the 64 works, 70 hematidrosis

incidents were revealed. The mean age of those who suffered was

25.6 years. The time expanse for case reports was 426 years

(Table I). The female sex was

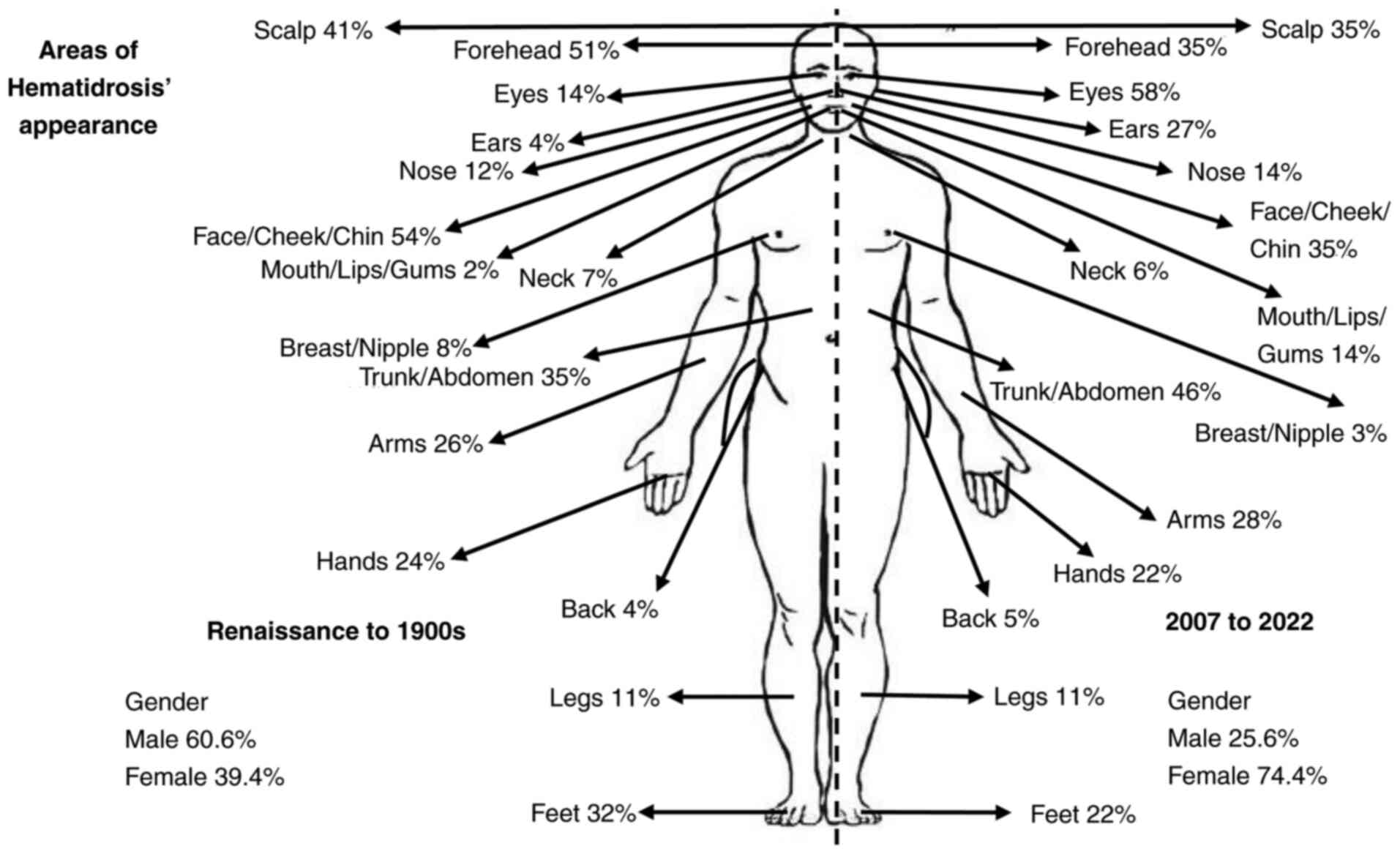

recorded in 39.7% of the affected individuals (Fig. 1). Articles in other languages (one

in Russian, one in Czech and two in Spanish) were excluded, as well

as some cases with no full texts (five works). A systematic search

of the current medical literature of the past two decades retrieved

56 articles, 37 of which were eligible for all data requirements to

have been included in the present review. Non-English articles,

nine in total, five publications with no abstract or text

available, and five overlapping publications were isolated and

excluded. Among the 37 articles identified, a total of 44 cases

were recorded. The mean age of the affected individuals was 15.8

years. The female sex exhibited a 74.4% dominance. The total time

span was 15 years (2008-2022) (Table

II). The number of articles on hematidrosis presents with a

peak during the second half of the 19th century and after 2007.

Until the end of 19th century, articles had appeared in Latin,

Italian, German, French and English languages, with English

language encompassing the majority of articles, followed by French

and Latin. Over past two decades, all articles are written in

English. A comparison of the bodily areas of the appearance of

hematidrosis between the two eras in question is demonstrated in

Fig. 1. Cases of famous

individuals, 26 in total, experiencing hematidrosis under stigmata

exposure are registered separately (Table III).

| Table IWorks with references to hematidrosis

cases from the Renaissance until 1900. |

Table I

Works with references to hematidrosis

cases from the Renaissance until 1900.

| No. | Original

authora | Case | Body locations of

hematidrosis | Work and year of

publication |

|---|

| 1 | Johannes Müller von

Königsberg (32)

(Regiomontanus) | Young boy accused

for a crime | Whole body | Ephemerides,

1474 |

| 2 | Leonardo da Vinci

(98) | Soldier departing

for battle | Forehead, whole

body | Ca 1503, La

Battaglia di Anghiari era (Malvin Pilato, The Memoirs of Dr.

Michael Arthur Creed, 2010) |

| 3 | Jacques Auguste de

Thou (17) | Italian officer of

Monte Maro fortress proposed to surrender or die | Whole body | Historia sui

temporis, 1560-1584, (French translation of 1711) |

| 4 | Jacques Auguste de

Thou (17) | Young Florentine

sentenced to death by Pope Sixtus V | Whole body and

tears | Historia sui

temporis, 1560-1584, (French translation of 1711) |

| 5 | Wilhelm Fabricius

von Hilden (23) | 12-year-old child

after drinking red wine | Gums, every part of

integuments, nose | Observationem et

curationem chirurgicam centuriae sex, 1606 |

| 6 | Wilhelm Fabricius

von Hilden (23) | 45-year-old widow

losing her only son | Upper part of the

body, back of the head, temples, eyes, nose breast, tips of the

fingers | Observationem et

curationem chirurgicam centuriae sex, 1606 |

| 7 | Henricus ab Heer

(23) | Man | Bloody sweat with

worm like coagulation | Observo

Medicinalis, ca 1600-1636 |

| 8 | Georg Spörlin

(24) | 12-year-old boy

with high fever | Whole body | Letter in Wilhelm

Fabricius Hildanus. In: Opera quæ extant omni, 1627 |

| 9 | Paolo Zacchia

(22) | Young man condemned

to die in flames | Whole body | 1628 (Quaestiones

medico-legales, 1621-1651) |

| 10 | François Eudes de

Mézeray (17) | Charles IX King of

France | Whole body (pores

and conduits) | Histoire de France

depuis Faramond jusqu'au règne de Louis le juste, 1643-1651 |

| 11 | François Eudes de

Mézeray (17) | Mayor of a town

destroyed by a heavy storm and condemned to die | Whole body | Histoire de France

depuis Faramond jusqu'au règne de Louis le juste, 1643-1651 |

| 12 | James Henry Pooley

(14) | Sailor during a

storm | Whole body | Memoirs of the

Society of Arts of Haarlem (Popular Science Monthly, 1884) |

| 13 | Thomas Bartholinus

(22) | Various cases after

vehement terror agonies of torture | Whole body | De nivis usu medico

observationes variae Chapter XXII, 1661 |

| 14 | Du Gard (32) | 3-month-old child

dying | Nose, ears, hinder

part of the head, fingers, toes | Philosophical

Transactions, 1674 |

| 15 | S. Ledelius

(25) | Woman nursing | Breasts | Sudor sanguineus.

Misc Curiosa, Sive, Ephemaridum MedicoPhysicarum Germanicarum,

1683 |

| 16 | Herman Boerhaave

(19) | Girl suffering from

cold finger syndrome | Whole body | Ca 1688-1720

(Index-catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon-General’s Office,

United States Army, 1889) |

| 17 | Johannes Franciscus

Vicarius (32) | Newborn boy | Right arm | De sudore cruento

frequentiore, Misc. Acad. Nat. Curios., 1694 (Magnet JJ.

Bibliotheca medico-pratica sive rerum medicarum thesaurus

Cumulatissimus, 1698) |

| 18 | S. Ledelius

(25) | Man with

scurvy | Whole body | Manget JJ.

Bibliotheca medico-practica sive rerum medicinarum thesaurus,

1697 |

| 19 | Ido Wolf (32) | 43-year-old man,

cranial trauma | Cranium | Observationum

chirurgico-medicarum libri II, cum scholiis & variis

interspersis historiis medicis, 1704 |

| 20 | J.C. Schilling

(32) | Boy in coma and

convulsive disorder | Whole body | Case of Bloody

Sweat, 1747 (Popular Science Monthly, 1884) |

| 21 | Antonii Mesaporiti

(32) | Young lady | Whole body | Epistola D. Antonii

Mesaporiti, M. C. Genuensis ad Cl. Antonium Vallesnerium, 1753 |

| 22 | Christiani

Ehrenfried Eschenbach (32) | Girl | Whole body | Sudor sanguineus;

urina sudore et vomitu rejecta, Observata

anatomico-chirurgico-medica rariora, 1769 |

| 23 | Albrecht Von Haller

(32) | Woman, uterus

cancer | Whole body | Anfangsgruende der

Phisiologie des menschlichen Koerpers, 1772 (Schneider in Fulda.

Medicinisch-chirurgische Bemerkungen uber verschiedne Gegenstande

ans der Heilkunde, 1848) |

| 24 | Gallandat (32) | 31-year-old boatman

with fatigue | Whole body | Sueur de sang. Soc.

Scient. Harlemensis, 1773 (Dictionnaire abrégé des sciences

médicales, 1822) |

| 25 | Josephi Lanzoni

(32) | Young woman

suffering from cholera morbus | Whole body | Case of Bloody

Sweat, Ephemerid. Acad. Natur. Curios., 1788 |

| 26 | John Mason Good

(32) | Various cases in

general regardless of age | Whole body | A History of

Medicine, 1795 |

| 27 | Boivin (33) | 45-year-old man

with depression and burn out syndrome | Whole body | Observation sur une

diapédèse, Journ. de Méd., Chir., Pharm, 1807 |

| 28 | F.C. Câizergues

(33) | Young lady | Face, neck, chest,

armpit | Sueur de sang

survenue quatre fois pendant la plus grande vivacité des douleurs

d’une colique néphritique. J. de Méd., Chir., Pharm., 1814 |

| 29 | James Johnson

(editor) (33) | 21-year-old woman

with irregular menstruation | Cheeks and

epigastrium | Transactions

Médicales, 1830 (The Medico-chirurgical Review, and Journal of

Practical Medicine, 1831) |

| 30 | Chauffard M.

(33) | 21-year-old woman

after a parental clash due to religious issues | Cheeks and

abdomen | Transactions

Médicales, 1830 |

| 31 | Maur Hoffmann

(22) | Man ~50 years of

age, fatigue | Arms and feet | Ca 1836, Misc Nat

Curios Dec II Ann III Obs 27 (Wochenschrift für die gesammte

Heilkunde: 1848) |

| 32 | Kaminsky (31) | Young girl | Feet | Tertianfieber mit

Ausschwitzung von Blut aus den Füssen. Med. Ztg., Berl., 1837

(Schmidt’s Jahrbuecher, 1838) |

| 33 | John Gideon

Millingen (15) | Catherine Merlin of

Chamberg, 46 years of age, received a kick from a bullock in the

epigastrium | Scalp and various

parts of the body | Curiosities of

Medical Experience, 1839 |

| 34 | C.A.W. Schneider

(31) | 50-year-old man,

fatigue 30-year-old male, fear | Feet Forehead,

cheek | Blutschwitzen.

Wochenschrift für die gesammte Heilkunde: 1848 |

| 35 | Durius (16) | Student placed in

prison | Hands, chest,

arms | (Misscel. cur.

Ephemerid.) The Cyclopædia of Biblical Literature, 1851 |

| 36 | Auguste Nicolas

Gendrin (33) | Young lady | Whole body | Des Sueurs de Sang,

1856 |

| 37 | Huss (31) | 23-year-old woman,

emotional stress | Whole body | Allg Med Cent

Zeitung Nr 97-98, 1856 |

| 38 | Erasmus Wilson

(41) | Women Woman | Forehead, chin,

cheeks | On the Diseases of

the skin, 1857 |

| 39 | Julles Parrot

(33) | 37-year-old woman

with hysteria | Face and various

parts of the body | Bulletin De

l’Enseignement Médiclae, 1859 |

| 40 | Thomas K. Chambers

(30) | 27-year-old

woman | Whole body,

nose | Case of Bloody

Sweat, Lancet, 1861 |

| 41 | F. Servaes

(31) | Man, dementia

paralytica Man, dementia paralytica | Face Face, scalp,

ear | Ueber Blutschwitzen

am Kopfe de Dementia paralytica. Centralblatt fur die Medicinischen

Wissenschaften, 1863 |

| 42 | A. von Franque

(21) | 45-year-old woman,

into pregnancy after a previous abortion | Forehead, back |

Medicinisch-chirurgische Monatshefte:

kritisches Sammeljournal für praktische Heilkunde. 1863 |

| 43 | G. Sous (36) | 9-year-old

girl | Right eye | 1866 (Annales

d’oculistique, Sueur sanguinolente, Tircher, 1869) |

| 44 | Ferdinand Ritter

von Hebra (21) | Female Female

Male | Caruncula

lachrymalis Nipples Lower limps | On Diseases of the

Skin, Including the Exanthemata, 1866 |

| 45 | McCall Anderson

(18) | 15-year-old girl

with defective and irregular menstruation | Face, chest, arms

and legs | Journal Cutan. M.,

Lond. (British Medical Journal), 1867 |

| 46 | Messedaglia &

Lombroso (84) | 23-year-old

man | Whole body | Giornale Italiano

delle Malattie Veneree e delle Malattie della Pelle, Volume 2,

1869 |

| 47 | W.T.P. Douglas

(84) | 35-year-old woman,

fatigue, tetanus | Forehead | Hematidrosis with

tetanus, 1870 (Sammuel Wilks, Hematidrosis or Bloody sweat

complicating tetanus, Guy’s Hospital Reports, 1872) |

| 48 | Schneider (16) | Sailors during a

storm | Whole body | The biblical

museum, 1871 |

| 49 | Samuel Wilks

(84) | Woman with

tetanus | Whole body | A case of

hæmatidrosis, or bloody sweat, complicating tetanus. Guy’s Hosp.

Rep., 1872 |

| 50 | Rudolf Ludwig Carl

Virchow (28) | Louise Lateau, | Forehead, dorsal

surface of the hands and feet | Professor Virchow

on Louise Lateau, The Medical Times and Gazette: A Journal of

Medical Science, Literature, Criticism, and News, 1874 |

| 51 | W.P. Hart (18) | 24-year-old young

man | Whole body | Richmond and

Louisville Medical Journal, 1875 |

| 52 | M. Tittel (29) | 20-year-old man

with fatigue | Face | A case of

Hematidrosis, Medical record: a monthly journal of medicine and

surgery, 1876 |

| 53 | McCall Anderson

(41) | 15-year-old young

lady with early menstruation | Face, arms, chest,

legs | Lectures on

Clinical Medicine, 1877 |

| 54 | R.G. Hill (42) | 4-year-old boy,

malaria | Face and neck | Case of bloody

sweat. Virginia M. Month., Richmond, 1879-80 (The Ohio Medical

Recorder, Volume 5, 1881) |

| 55 | George William

Pollard (42) | 4-year-old boy

patient of Dr Hill R.G. suffering from malaria | Whole body | Virginia Medical

Monthly, 1880 |

| 56 | W. T. Mitchell

(42) | Woman, irregular

menstruation | Whole body | Case of

Hematidrosis. Ohio Med Recorder, 1881 |

| 57 | Juan De Maldonato

(13) | Man from Paris

sentenced to death | Whole body | A commentary on the

Holy Gospels, 1888 |

| 58 | Hehir (93) | 16-year-old

girl | Head, axillae | Indian Medical

Record (The Medical News, 1893) |

| 59 | Friedrich Albin

Hoffman (22) | Man | Feet | Lehrbuch der

Constitutionskrankheiten, 1893 |

| 60 | James Craven Wood

(27) | 6-year-old girl

with cicatrized fingers after strumous ulcers on the right hand

when 7 months old | Fingers, knees,

thighs, chest and grooves of the lower eyelids | A Text-book of

Gynecology, 1894 |

| 61 | Isadore Dyer

(26) | 26-year-old

American rubber in a local Turkish bath, fatigue | Shoulders | A Case of

Hematidrosis Combined with Chromidrosis, The Medical News,

1895 |

| 62 | R. Reynolds

(38) | Various cases

suffering from smallpox | Face | Report of the

Department of Health of the City of Chicago, 1895 |

| 63 | Henri Fournier

(32) | Magistrate after

any excitement | Whole body | Journal des

maladies cutanées et syphilitiques, 1896 |

| 64 | Alma L. Rowe

(5) | Pregnant woman | Whole body | Purpura

Hemorrhagica Attended with Hematidrosis Complicating Pregnancy,

Journal of the American Medical Association, 1900 |

| Table IIWorks with references to hematidrosis

cases from 2002 until 2022. |

Table II

Works with references to hematidrosis

cases from 2002 until 2022.

| No. | Author(s) | Person | Body locations of

hematidrosis | (Refs.) |

|---|

| 1 | Manonukul et

al | 14 years old

girl | Scalp, palms, and

occasionally from trunk, soles, and legs | (2) |

| 2 | Carvalho et

al | 9-year-old girl

after strenuous exercise or prolonged exposure to heat | Around the

mouth | (49) |

| 3 | Mishra | 13-year-old girl

with platelet factor 3 dysfunction | Eyes | (72) |

| 4 | Jerajani et

al | 72-year-old male,

suffered from continuous mental stress | Area confined to

the abdomen | (56) |

| 5 | Bhagwat et

al | 12-year-old girl,

horrifying incident with psychological stress | Forehead | (51) |

| 6 | Patel and

Mahajan | 13-year-old boy

with no underlying disease | Face, arm and

trunk | (74) |

| 7 | Wang et

al | 13-year-old girl,

emotional excitement | Subungual area,

palms, feet, thighs, and trunk | (59) |

| 8 | Praveen and

Vincent | 10-year-old girl,

severe headache lasting for few hours on facing stressful

situations | Forehead, ear

canal, nasal bridge, neck, umbilicus, wrists and legs,

hemolacria | (50) |

| 9 | Mora and Lucas | 18-year-old girl,

high stress | Nose, lacrimal

ducts, forehead, hands, nails, and navel | (48) |

| 10 | Bhattacharya et

al | 12-year-old girl

with no underlying disease | Face, limb, palm

and sole | (46) |

| 11 | Biswas et

al | 12-year-old healthy

girl with low intelligent quotient and loss of insight | Forehead, face and

body | (77) |

| 12 | Khalid et

al | Female crying as a

result of emotional outburst or even sometimes voluntarily | Eyes and ears | (82) |

| 13 | Tshifularo | 30-year-old woman,

stress 26-year-old woman with no underlying disease 34-year-old

woman, stress 18-year-old woman, stress | Bloody

otorrhea | (63) |

| 14 | Deshpande et

al | 10-year-old boy,

behavioral interventions for the child and counseling and

psychoeducation to the parents | Navel, eyes, ear

lobules and nose | (76) |

| 15 | Shen et

al | 9-year-old girl

with no underlying disease | Various parts of

the skin on her body, canthi, tongue, nails or Umbilicus | (69) |

| 16 | Varalakshmi et

al | 10-year-old girl,

significant psychological stressors, temperamental difficulties and

conflicts with mother | Eyes | (52) |

| 17 | Jafar and Ahmad

al | 12-year-old girl

with no underlying disease | Face, eye and tear

duct | (60) |

| 18 | Techasatian et

al | 9-year-old boy

after a novice monk summer retreat | Scalp, cheeks,

palms, arms and legs | (57) |

| 19 | Yeşilova et

al | 11-year-old girl

when returning from outside cold air into a warm Environment | Forehead | (61) |

| 20 | Maglie and

Caproni | 21-year-old woman,

depression and anxiety disorder | Palms and face | (65) |

| 21 | Gião Antunes et

al | 66-year-old male

with Henoch-Schönlein Purpura | Hemolacria (bloody

tears), hematidrosis and appearance of a palpable purpura on the

lower limbs, abdomen, and trunk | (55) |

| 22 | Jayaraman et

al | 10-year-old girl,

intense fear secondary to psychosocial stressor,mixed anxiety and

depressive disorder | Scalp | (68) |

| 23 | Shahgholi | 11-year-old girl

with no underlying disease 11-year-old boy with no underlying

disease 9-year-old girl | Forehead, eyes,

ears, nails, arm, umbilical area, back, vagina, and

gastrointestinal tract Hand and feet Ears lobules, nose and

eyes | (58) |

| 24 | Alsermani et

al | 9-year-old girl,

bullying at school | Scalp, ear, mouth,

and eyes | (4) |

| 25 | Meyer et

al | 10-year-old girl,

post-traumatic | Forehead | (62) |

| 26 | Hansson et

al | 9-year-old boy,

migraine | Forehead, neck,

knee and mouth | (54) |

| 27 | Pari | 10-year-old girl

with no underlying disease | Forehead and

chest | (73) |

| 28 | Ricci et

al | 15-year-old girl,

major stressful event | Eyelids and

body | (79) |

| 29 | Murota et

al | 6-year-old girl

with no underlying disease | Palms | (64) |

| 30 | Dast et

al | 15-year-old girl

following a head injury 13-year-old girl, anxiety | Ears, nose and eyes

Face, eyes, shoulders and forearm | (78) |

| 31 | Matsuoka and

Tanaka | 11-year-old girl

presenting dissociative disor ders from the age of 7 and

self-harming from 9 | Scalp, forehead,

hands and feet | (80) |

| 32 | Shafique et

al | 10-year-old girl,

experiencing significant psychosocial stress due to the recent

separation of her parents | Eyelids, ears,

scalp, axillae, vagina, rectum, abdomen, chest, neck, and

trunk | (47) |

| 33 | Hoover et

al | 9-year-old boy,

possible genetic predisposition 6-month-old girl | Ears, eyes, scalp

and other sites Ears, eyes, scalp and other sites | (89) |

| 34 | Talwar et

al | 12-year-old boy,

separated from relatives, maladaptive response to a psychosocial

stressor | Eyes, ear,

mouth | (53) |

| 35 | Tirthani et

al | 13-year-old girl,

orphan girl living with her paternal uncle and cousins | Mid face and

hands | (81) |

| 36 | Zheng et

al | 8-year-old girl,

single parent (mother) | Mouth, eyes,

forehead, oral, arms and legs and intestine | (44) |

| 37 | Alasfoor et

al | 20-year-old woman,

retinoblastoma of the left eye with enucleation and artificial eye

placement, prolonged and heavy menstrual cycles and neurological

symptoms | Eye | (45) |

| Table IIISome cases of famous people bearing

stigmata with hematidrosis. |

Table III

Some cases of famous people bearing

stigmata with hematidrosis.

| No. | Person | Canonized |

|---|

| 1 | Marie d'Oignies (ca

1177-1213) (100) | No |

| 2 | Saint Francois

d'Assise (1181-1226) (97) | Yes |

| 3 | Helen of Hungary

(d. ca 1241) (100) | No |

| 4 | Cistercian nun

Lutgard of Aywiéres (1182-1246) (100) | No |

| 5 | Clare of Montefalco

(ca 1268-1308) (100) | No |

| 6 | Margaret Ebnerin

(d. ca 1351) (100) | No |

| 7 | Gertrude D'Oosten

(d. ca 1358) (100) | No |

| 8 | Sainte Catherine de

Sienne (1347-1380) (97) | Yes |

| 9 | Saint Liduina of

Schiedam (1380-1433) (100) | Yes |

| 10 | Sainte Rita de

Cascia (1381-1457) (97) | Yes |

| 11 | Bienheureuse Lucie

de Narni (1476-1544) (97) | No |

| 12 | Sainte Catherine de

Ricci (1522-1590) (97) | Yes |

| 13 | Hieronyme Carvaglio

(d. ca 1604) (100) | No |

| 14 | Sainte Véronique

Giuliani (1660-1727) (97) | Yes |

| 15 | Bienheureuse Anne

Catherine Emmerick (1774-1824) (97) | No |

| 16 | Maria Theresia von

Mörl (1812-1868) (97) | No |

| 17 | Maria Domenica

Lazzeri (1815-1848) (97) | No |

| 18 | Maria Beatrix

Schuhmann (1823-1887) (97) | No |

| 19 | Juliana Weiskircher

(1824-1862) (97) | No |

| 20 | Sainte Mariam

Baouardy (1846-1878) (100) | Yes |

| 21 | Louise Lateaua

(1850-1883) (97) | No |

| 22 | Madeleine Lebouca

(1853-1918) (100) | No |

| 23 | Sainte Gemma

Galgani (1878-1903) (97) | Yes |

| 24 | Saint Pio de

Pietrelcinaa (1887-1968) (97) | Yes |

| 25 | Thérèse Neumanna

(1898-1962) (97) | No |

| 26 | Marie Rose Ferron

(1902-1936) (97) | No |

4. Hallmarks in history

The phenomenon of sweat which resembles blood was

coined to the observations noted in medicine by the ancient Greeks.

Hematidrosis appeared as an affliction from the unbroken surface of

the skin and greatly attracted the interest of scholars,

medico-philosophers and theologians of antiquity. Aristotle was the

first to mention bloody sweat in two fragments of his works, ‘if

blood gets too wet people get very weak. It becomes like ichor

(pus, coagulation disorders) and appears so that many have seen

bloody sweat’ (7), and ‘Instances,

indeed, are not unknown of persons who in consequence of a

cachectic state have secreted sweat that resembled blood’ (8). Theophrastus the philosopher, the

successor of Aristotle in the Peripatetic School also mentioned

that ‘sometimes with sweat blood appears’ (9). The Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus,

in his masterpiece entitled Bibliotheca Historica reported cases of

individuals bitten by snakes tormented with pain and seized with a

bloody sweat (10). The

Pseudo-Gallenic collection of works mentioned sweat with blood into

two books, ‘De Utilitate Respirationi’ (Latin text, paraphrasing

the reports of Aristotle) and ‘De Humoribus Liber’ (Greek text,

sweats in spring and summer produced by having blood and bile)

(11). Marcus Annaeus Lucanus

noted that the human body could emit humor, such as blood from

various areas such as the limbs and nostrils (12). Hematidrosis was connected with

acute anxiety in the case of Jesus Christ prior to his arrest and

crucifixion inside the gospel of the physician and evangelist Luke,

where Christ is reported to sweat large drops of blood when he was

praying with agony in the garden of Gethsemane (Luke 22:44)

(13). This report further

enhanced curiosity as opposed to the phenomenon itself, resulting

in numerous references by scholars throughout the next centuries

and fanatic religious to state that they also similarly suffer.

Kings, state officials, military officers and common individuals in

agony under fear or hysteria were reported as cases of hematidrosis

until the 19th century (14-31).

A. Westphal wrote one of the first post-medieval dissertations on

the subject, entitled De Sudore Sanguineo in 1775(32). The article of Jules Parrot's

entitled ‘Study of bloody sweat and neuropathic hemorrhage’ in 1859

was considered in its era the most essential work on the subject.

This original work attracted attention to the appearance of

cutaneous hemorrhages and hematidrosis during paroxysms of a

neuralgia, which was extremely severe and variously located

(17,33). For some researchers, hematidrosis

was classified as an entity related to hemophilia (Greek term

meaning friendship for blood) (34), characterized by the suddenness of

appearance with various outbreak patterns, connected sometime with

the vicarious menstruation (35).

It was also closely related to the central nervous paralysis and

hysteria, to ecstasy, to agony, to convulsion (spasms), to

hallucinations and in general in neurology disorders, reported as a

rare symptom (36,37). According to the beliefs of the

epoch, blood pure, or mingled with sweat could appear on the

surface of the skin in the form of drops or issues from the

glandurar openings (pilo-sebaceous, Meibomian, ceruminous) in tiny

jets. Moreover, dermatorrhagia (bleeding from the sub-epidermic

vascular network) could occur simultaneously and the condition have

also been considered as a form of hyperhidrosis with fatal

symptomatology (weakness, anemia, syncope and death) (38).

The most prolific complete treatise on the subject

of hematidrosis was this of Ernst Ziegler in 1895, naming

hematidrosis as diapedesis. Diapedesis of the blood through

uninjured walls of vessels was considered as something peculiar and

a different form the hemorrhage produced by ruptured ones when a

rhexis (Greek term for rupture) occurs. This occasional spontaneous

oozing of arterial blood from the sweat glands was studied by

microscopy and was attributed to the rise of pressure in the

capillaries and small veins combined with increased permeability of

the vessel walls. As for the hemorrhagic diathesis (Greek term,

meaning temper), this had been divided into congenital or

hereditary and acquired. A large cluster of diseases could enact

the provocation of hematidrosis, named scurvy, morbus maculosus

Werlhof, purpura simples, purpura rheumatic, purpura haemorrhagica,

melena neonatorum, septicemia, endocarditis, malignant pustule,

spotted typhus, cholera, smallpox, plague, acute yellow atrophy of

the liver, yellow fever, nephritis, phosphorus poisoning,

snake-bites, malnutrition, irritation or paralysis of the

vaso-mottor nerves, moral shock, terror, thrombosis or embolism or

ligation of a vessel complicated with stagnation and many more. The

female sex was most vulnerable against diapedesis. Psycho-therapy

and palliative interventions were suggested (39). Geranium, a genus of 422 species of

plants, was proposed to help confront hematidrosis (40). The treatise of Ziegler was

published the same year with Moriz Kapozi's masterpiece Pathology

and Treatment of the Disease of the Skin. However, Kapozi only

mentioned the occasional spontaneous oozing of arterial blood from

the sweat glands, named hematidrosis, considering it as the rarest

case of cutaneous hemorrhage (41).

The terrifying nature of the hematidrosis phenomenon

impressed the mind of medical observers and conquered the souls of

the uneducated population to assume an almost miraculous character.

Diapedesis on the forehead, hands and feet was stated to occur in

religious bigots considered by fanatics as a gift of holy marks and

bloody sweat of the Christ named stigmata. Those cases, following

careful scientific examination, had proven to be, at least most of

them, in the sphere of religion and faith or somehow fictitious.

Religion enthusiasts bearing hematidrosis made their appearance

from time to time mostly in the area of the Catholic church,

stating the ability to reveal and confess the real work of God.

Even publications were encountered in the form of Letters (famous

type of text in religion). Hyperboles, such as for public

demonstrations of hysteric or cataleptic poor peasant girls being

visited by hundreds of wondering spectators ready to worship them

and references of persons that had not slept or eaten for 8 years,

compelled scientists to refer to them as simply impostors (14).

Charles T. Scott was the first to publish in PubMed

in 1918 under the term haematidrosis, reporting the case of

abnormal perspiration of a pink fluid on the forehead of an

11-year-old girl with a nervous temperament (42). Almost a century later, Joe E.

Holoubek and Alice B. Holoubek in 1916, two devoted catholic

physicians, performed an extensive literature review based upon a

selection of 76 cases of Pooley's review ranging from the 17th

century to 1980. They had classified all cases under subgroups

according to the etiology: Systemic disease (e.g., scurvy and

lupus), vicarious menstruation, physical exertion, psychological

stress (repeated or unique), religious stigmatics and idiopathy

(43). Moreover, 2 cases were

reported during 2022 in the PubMed/MedLine database (44,45).

5. Findings in the modern literature

Hematidrosis depicts an eccrine sweat disorder,

strongly characterized by one or more transient, yet recurring

episodes of a spontaneously mixed fluid of sweat and blood from the

intact epidermis. Although it presents a notoriously rare and

fascinating condition, the prevalence and incidence of this

condition remain unknown, as illustrated by the small number of

cases published and the almost complete absence of case series.

However, over the past two decades the number of cases and studies

has increased, despite the fact that most of the cases which have

been reviewed displayed a stereotypical presentation of bleeding

pattern, background etiogenesis and therapeutic approach (1,4).

Female patients presented the majority of the cases, mainly young

between the ages of 9 to 15 years (46-52).

Male patients have been less frequently reported, but are usually

also at a young age (53,54) with a small number of exceptions of

patients >65 years of age (55,56).

The geographic distribution testifies a tendency towards the Asian

region (India and Pakistan) as one of the two cases of those

reported refers to the Indian population. A genetic predisposition

was proposed to explain this geographic predilection (1,4).

The most common areas of appearance of the

phenomenon, without being limited to these, are namely the

forehead, scalp, face, eyes and ears, and secondary trunk and

limbs. The majority of the cases were clinically examined and

interdisciplinary observed by more than one specialized physician,

as in numerous reports, there were suspicions that the symptom may

be factitious (5). Moreover, in

some reports, the diagnosis was based only on clinical criteria

with insufficient laboratory examinations, accompanied by a

misdiagnosed hypothesis of self-traumatism. However, fully

clinically examined patients, undergoing histopathological

examinations, is the trend observed over the past decade (57). Psychiatric disorders and severe

stress have been proposed (1,58-60),

while a post-traumatic appearance has been reported by 61. Yeşilova

et al (61) and Mejer

(62). Various areas of appearance

may be noted in a multiple concurrent emergence. Οtorrhea,

hematuria, epistaxis, bleeding from the intestines the oral cavity

and the eyelids have also been mentioned (1,41,59,60,63).

Pathology usually reveals a free medical history, and records have

demonstrated no family incidents; laboratory tests of complete

blood count, coagulation, immunology, renal and liver function have

yielded inconclusive results (60). Dermatological evaluation have

disclosed no cutaneous lesions. Histological findings following

skin biopsy have ranged from congested blood vessel capillaries,

extravasation of erythrocytes within the follicular lumen, leakage

of red blood cells in dermis, or even just normal skin layers

(1,2,43).

In a case where an increased number of CD34-positive cells were

observed around the eccrine sweat glands in a young female with

palmar hematidrosis, the authors suggested that high pressure

applied in the plantar surface of the hand (horizontal bar

exercise) subsequently damaged the balance of her small blood

cells, thus increasing the CD34-positive cells (64). As regards diagnosis, the following

criteria have been suggested: i) testified bleeding by medical

personnel; ii) red blood cell detection in the examination

exudates; iii) the absence of trauma, self-injury, telangiectasias,

purpura and no evidence of oozing after wiping of the area

(65). Differential diagnosis

included self-injury, vasculitis, connective tissue disorders

(increased vascular fragility and secondary bleeding), Munchausen's

by proxy syndrome, scurvy, hematomas, petechial, purpuric lesions,

pseudochromhidrosis, and chromhidrosis and psychogenic purpura

(5,62,66).

To avoid confusion, it must be noted that chromhidrosis is

characterized by the excretion of colored sweat from eccrine sweat

glands, while pseudochromhidrosis sweat is colorless, later

acquiring color due to its contact with chromogenic chemicals of

the skin (66,67).

The patho-physiolgical mechanisms involved in the

development of hematidrosis are not completely clarified. It has

been calculated that half of the cases of hematidrosis remained

with an undetermined causative etiology. The rupture of the small

capillaries that supply sweat glands has been suggested to be the

key factor of blood seepage (1).

Physical fatigue and emotional stress, fear of death, school

examinations, interfamily conflict and orphanage are being

indicated as the most frequent triggers of this condition (1,68).

Tonic seizures resolved with anti-epileptic medication may cause

hematidrosis, as recorded in a 9-year-old girl by Shen et al

(69) in 2015. It has been

hypothesized that the hyper-reactivity of the sympathetic nervous

system following a major or acute stressful event, may result in

vessel vasoconstriction, altering the blood supply to the eccrine

glands. In the post-stress phase as vasodilatation occurs, tinny

ruptures of the nutritional vessels of the sweat glands occur and

the secretion of bloody sweat droplets to the skin is implemented.

A distinctive vasculitis with intra-dermal bleeding and obstructed

capillaries has also been reported as the pathological basis of

hematidrosis cases (70,71). Platelet factor-3 dysfunction has

been also implicated (72).

Currently, there is no available treatment of

choice. The benign and transient nature of the disease should be

explained to the family and caregivers. Convincing the parents

about the nature of the disease is mandatory for the successful

management of any case. Moreover, holistic emotional support of all

implicated appears to be of paramount importance (72-76).

Personalized therapy and individualized interventions based on the

needs of patients and caregivers are strongly recommended. The

reduction of anxiety followed by the administration of

benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam and diazepam has been proven

efficacious (1,60). Hemostatic drugs and vitamin C are

being used without any notable results. Some cases have responded

to atropine transdermal patches (77), while others to adrenaline gauze

wipes (73,75). The administration of β-adrenoceptor

antagonists has been reported to be an effective treatment for

hematidrosis by regulating sympathetic nervous system activation

and reducing intense psychological excitement (4,47,78-80).

Wang et al (59) in 2010

reported a complete resolution and recovery of the bleeding

episodes in a 13-year old girl treated with propranolol.

Oxybutynin, an anticholinergic drug, was successfully used in a

13-year-old patient (81). There

are cases reporting that apart from medical personnel, patients

were searching for various spiritual treatments, homeopathy and

quackery (personas who fraudulently sell a product or service to

supposedly cure a patient) (82).

6. Summary and deliberation of

hematidrosis

Diapedesis from the plexus of the vessels

surrounding the sweat glands has intrigued scholars and scientists;

this has led to the appearance of records in medical and historical

books. Shallow skepticism of the medical community denied the

phenomenon for centuries, until only when it was directly observed.

Apart from plausibility, failure to evolve a comprehensive

explanation contributed further to its delayed acceptance.

Disbelief strengthened by the fact that recorded cases were being

described sporadically and in a number of cases, by completely

unrelated authors (83).

A plethora of studies refer to Aristotle as the

first to describe hematidrosis. That is not entirely accurate.

Aristotle in his work ‘On the Parts of Animals’, truly described

bloody sweat, but as a peculiarity observed in the animal kingdom,

but not in humans. He only noted that it is known to exist. Some

animals exude reddish fluids from the surface of the skin. This

blood-colored exudation is due to color globules, and not merely to

blood in the case of the hippopotamus. Flamingos secrete red fluids

by their stomachs (84). The

observation of domestic animals, horses and cattle reveals more

representations of livestock manifesting incidents of real bloody

sweat (85). There is also some

confusion as regards the referrak to Galen as the pioneer to

understand hematidrosis. There was an old treatise titled ‘De

utilitate respiration’ bearing the same name given by Galen to one

of his works. It was paraphrased by the physician, Richard Mead, in

his 1749 publication on the bloody sweat of Jesus Christ. Since

then, it was globally celebrated as a true work of Galen's

Collection. Nevertheless, the remark was noted by some other

scholars who wanted to draw additional attention by falsifying the

name of the Greek majesty. Nevertheless, references for bloody

sweat exist only in the pseudogalenic texts (43). To verify this fact, the authors

analyzed and made a translation of 3,054 of Galens' references to

blood (αίµα) and 78 to sweat (ιδρώτας) by accessing TLG, resulting

in no possible much for such a case.

The Latin terms, sudor cruentus and sudor

sanguineus, first appeared in 18th century medical dictionaries and

indexes of the era. Hellenic-derived spellings of h[a]e

[o]mat[oh/h]idrosis appeared at a later date, during 1854(43). Apart from the name of the disease,

hematidrosis itself, various terms of Hellenic origin are connected

to its pathology, such as H[a]emorrhage (blood outflow), hemolacria

(blood in tears), otorrhea (outflow from the ears), otorrhagia

(blood outflow from the ears) and epistaxis (blood drip from the

nose) (86,87). Terminology only implies for an

emotive entity in skin pathology. Otorrhagia appears in more

articles in PubMed Central than hematidrosis. Authors worldwide

have only heard about rare bleeding disorders, and yet, they

believe their existence. However, this is not valid concerning

cases of hematidrosis, as for many, it depicts a rather

controversial theme. This, raises the question of who to choose for

reader or reviewer for such an article (88). Cases such as the one reported by

Hoover et al (89), of two

siblings presenting hematidrosis, apart from witnessing genetic

predisposition, further complicates emotions and beliefs.

In both eras investigated, during the 15th-19th

century and the past 20 years, the female sex has been registered

as the dominant inside scientific texts. However, the numbers of

reported cases prior to 1900 are markedly lower when comparing with

those reported over the past two decades. Masculine restrictions,

deficiency in physical strength and limitations to intellectual

developmental activities had undermined the education and

intelligence of the female sex and particularly that of younger

females of the humbler social casts (90). In many cases, young girls

presenting hematidrosis were peregrinated for religion and profit

reasons being considered as stigmatics gathering pilgrims and coin.

Although a bleeding episode of a young girl may cause

embarrassment, social isolation, panic and depression, the majority

of those girls never attended a physician or registered as an

official case (14). This fact may

also explain the following: i) The difference in mean age, which

was 25.6 years until 1990 and 15.8 years over the past two decades,

when presumably all cases were examined by health professionals;

and ii) the female sex percentage recorded until 1900 was 39.4%,

while that over the past two decades increased into 74.4%. The

analogy report of the anatomical areas of bloody sweat oozing

through the skin demonstrates that in both eras, the scalp,

forehead, face, arms, trunk and feet are the most commonly recorded

regions, while the ears, eyes and mouth demonstrated considerably

higher numbers in later years. The time period of the past 15 years

presents the highest peak of all time concerning papers on

hematidrosis, with the second half of the 19th century to follow

(5,43). The second industrial revolution

marked the second half of the 19th century, provoking acute social

changes, while nowadays, the excessive and harmful use of

technology, such as cell phones, video games, personal computers,

the internet and in general, the modern way of life, greatly

aggravate psychological side-effects such as anxiety, stress and

depression, while the youth are often associated with emotional and

behavioral issues. Increased psychic disorders increase all

diseases associated, perhaps explaining the increase in the

incidence of hematidrosis (91,92).

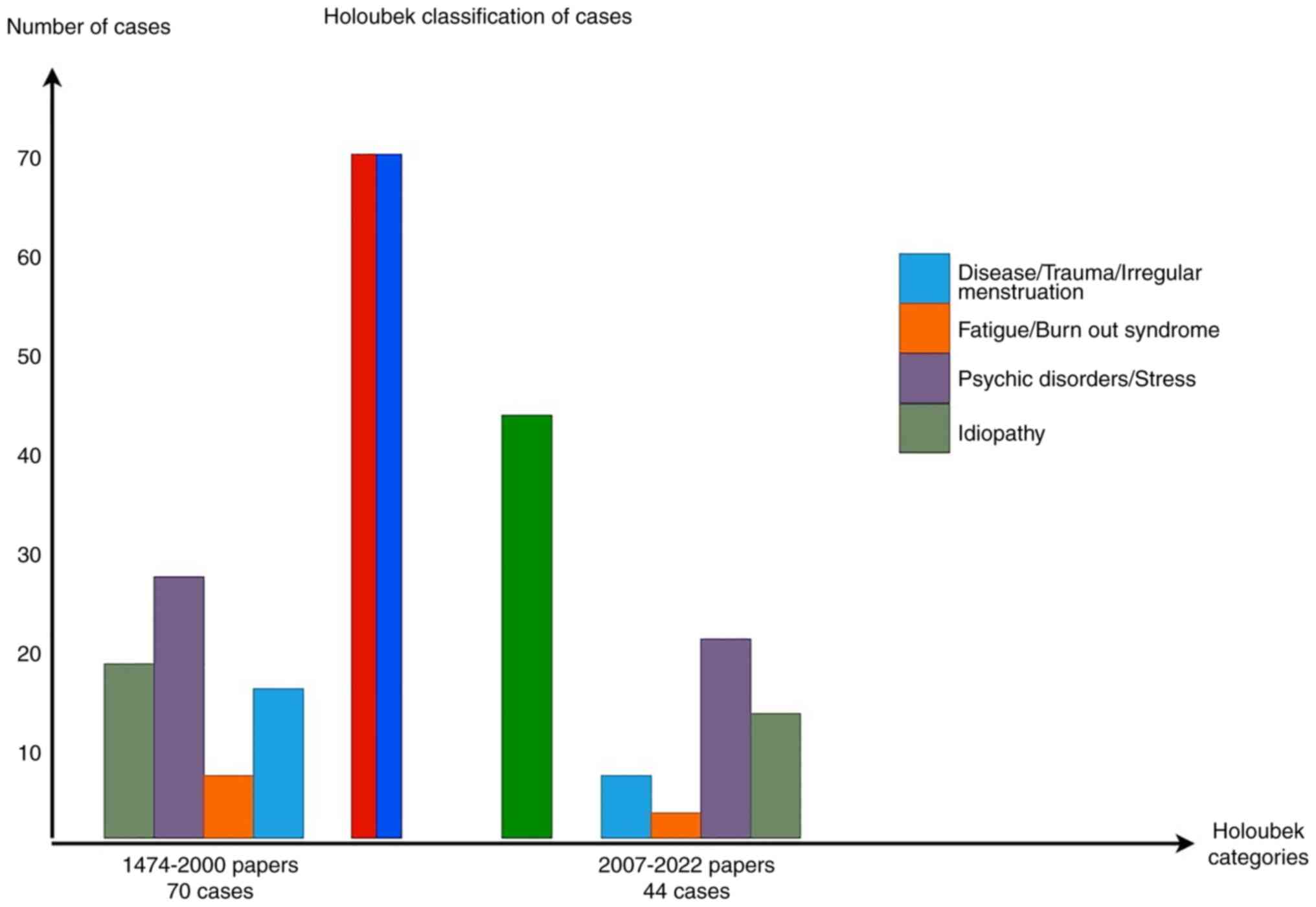

Articles categorized according to the classification of

hematidrosis by Holoubek and Holoubek (43) are demonstrated in Fig. 2, where psychotic

disorders/stressful events constitute the main trigger factor in

both eras. With the exception of the case described by Dr Hehir in

India, all other references until 1900 were reported from areas of

the European continent, while in the modern literature, the

majority of cases are recorded in India, or in Asia. The geographic

limitation of reports from Europe may be explained by the medical

achievements and progress mainly due to Western European

intellectual evolution through the ages, rendering this region as

the major point of quotation (93). English works until 1900 comprised

45.3%, while this number increased to 80.4% over the past two 2

decades. To support geography and language results, English was

cited as a universal language and globalization of the medical

references.

Jesus Christ when reacting to his future and known

to him torturous death, he had experienced a passionate agony, an

intensified stressful juncture of emphatic emotions, which flared

up as epistaxis. A number of medical writers still insist that

blood fell to the ground. Richard Mead in his 1749 work was the

first to notice and record that actually it was thromboi (clots of

blood) which touched the earth. The reddish fluid was thick and

viscous and rapidly coagulated (94,95).

The Hellenic term stigma was used to reproduce the optical

portraiture of the agony bleeding, crucifixion nails, thorny crown,

vinegar sponge, lash and spear wounds, which had been inflicted to

the palms, soles, head, chest, lips and back of Christ. Stigma in

Greek antiquity indicated a bloody wound or a sign marked on a

slave, while during the cultural spread of Christianity, it

acquired a more mystical meaning. Nuns, priests, saints, common

frauds and deep believers all experienced among other painful

effects, hematidrosis. Stigmata have never been studied under the

prism of a medical scientific approach until the review by

Kechichian et al (96) in

2018. A cluster of symptoms received by God is reported, including

painful purpura, erosions, blisters, scars and bleeding through the

epidermis with intact skin layers. Hematidrosis, the symptom of

interest, presents an obvious interaction between skin and psyche.

In a state of ecstasy, a pure believer may endure the agony felt by

his God, triggering the over-activation of the sympathetic nervous

system. An acute induce of a sympathetic response of the autonomic

nervous system may be held responsible for the vascular mechanisms

behind hematidrosis (96).

Although the conscious and voluntary fabrication or exaggeration of

physical and psychological symptoms for personal gain of frauds do

exist, physicians must have in mind the case of an almost ‘pure in

life’ true believer who may experience in the reality of his mind,

the passion of the Christ and in some cases, being canonized.

Hematidrosis is a condition which remains one of gruesome

fascination, but of great psychological suffering for the victim.

Neurology, psychiatry, dermatology, angiology and religion must

interact to explain some aspects (96-100).

7. Conclusions

Throughout the ages, a rarity in daily practice, a

sporadic reference in textbooks, an enigma in medicine, a malady

that may lead to extensive unnecessary laboratory tests and to

hazardous therapeutic interventions, hematidrosis is a spectacular

manifestation in skin pathology. It depicts a field where science,

the unknown and religion intertwine. The derma, psyche and faith

create a triad to explain diapedesis. For some medical personnel,

the condition appears to be an inconceivable phenomenon. For others

it is merely an ailment. For the Catholic church, hematidrosis in

stigmata constitutes an almost divine phenomenon. As medicine

without religion is a science disabled, to paraphrase the words of

Einstein, the present review highlights the pathology and

illustrates the necessity to believe in both, in order to

comprehend the peculiarities of nature. Nevertheless, blurred

etiopathogenesis, transdiagnostic variables, interdisciplinary

teams of health professionals, symptomatic and inconclusive therapy

and blood cells mixed with sweat are the only data that may be

presumed as certain.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

GT, DA and ES were involved in the intellectual

content of the review. GT, DA, AK and NP were involved in the

literature search. GT, DA and ES were involved in the acquisition

of data from the literature. GT, ES and KK were involved in the

analysis from the literature for inclusion in the review. GT and ES

were involved in the preparation and editing of the manuscript. ES,

KK and DAS were involved in the reviewing of the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

DAS is the Editor-in-Chief for the journal, but had

no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence

in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article.

The other authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kluger N: Hematidrosis (bloody sweat): A

review of the recent literature (1996-2016). Acta Dermatovenerol

Alp Pannonica Adriat. 27:85–90. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Manonukul J, Wisuthsarewong W, Chantorn R,

Vongirad A and Omeapinyan P: Hematidrosis: A pathologic process or

stigmata. A case report with comprehensive histopathologic and

immunoperoxidase studies. Am J Dermatopathol. 30:135–139.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Whitney DW (ed): The Century Dictionary

and Cyclopedia. The Century Co., New York, NY, 1889.

|

|

4

|

Alsermani M, Alzahrani H and El Fakih R:

Hematidrosis: A fascinating phenomenon-case study and overview of

the literature. Semin Thromb Hemost. 44:293–295. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Duffin J: Sweating blood: History and

review. CMAJ. 189:E1315–E1317. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 29(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Aristotle: Animal History [Historia

animalium, ed. P. Louis, Aristote. Histoire des animaux], vols.

1-3. Les Belles Lettres, Paris, 1:1964; 2:1968; 3:1969: 1:1-157;

2:1-155; 3:1-145, 156-175. Lib. 1-4 (486a5-538b23): vol. 1. Lib.

5-7 (538b28-588a12): vol. 2. Lib. 8-10 (588a16-633b8,

633b12-638b36): vol. 3, 1876.

|

|

8

|

Louis P (ed): Aristotle: On the Animal

Parts [De partibus animalium. Les parties des animaux]. Les Belles

Lettres, Paris, pp1-166, 1956.

|

|

9

|

Wimmer F (ed): Theophrastus Phil:

Fragments [Fragmenta, Theophrasti Eresii opera, quae supersunt,

omnia]. Didot, Paris, pp364-410, pp417-462, 1866.

|

|

10

|

Diodorus Siculus: Library [Bibliotheca

Historica]. Georgiadis, Athens, 2010.

|

|

11

|

Kühn CG (ed): Pseudo-Galenus: Works [De

utilitate respiration & De humoribus liber]. Vol 19. Knobloch,

Liepzig, pp485-496, 1830.

|

|

12

|

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus: Pharsalia [M.

Annaei Lucani Pharsalia]. Bell, London, p348, 1827.

|

|

13

|

Luce: The Gospel of Luce by Howard

Marshall. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rabids, 1978.

|

|

14

|

Pooley JH: Bloody Sweat. The Popular

Science Monthly, Appleton and Company, New York, NY, 1885.

|

|

15

|

Millingen JG: Curiosities of Medical

Experience Revised and Considerably Augmented. Richard Bentley,

London, 1839.

|

|

16

|

Gray CJ: The Biblical Museum. Elliot

Stock, London, 1871.

|

|

17

|

Parrot J: Study on blood sweat and

neuropathic hemorrhages [Étude sur la sueur de sang et les

hémorrhagies névro-pathiqués]. Bulletin De l'Enseignement Médicale,

pp633-635, 1859.

|

|

18

|

Hart WP: On Bloody Sweat. The London

Medical Record: A Review of the Progress of Medicine, Surgery,

Obstetrics and the Allied Sciences. Smith, London, 1875.

|

|

19

|

Moore J: Index-catalogue of the library of

the surgeon-general's office. United States Army. U.S. Government

Printing Office, Washington, DC, 1889.

|

|

20

|

Banberger H, Foerster A and von Scanzoni

F: Stahel's book and art negotiation [Wurzburger Medichinische

Zeitschrift]. Stahelschen Buch und Kunstverhandlung, Wurzburg,

1864.

|

|

21

|

Casper JL: Weekly Medical Magazine,

Editorial [Wochenschrift fur die gesammte Heilkunde]. August

Hirschwald, Berlin, 1848.

|

|

22

|

Hoffmann FA: Textbook of Constitutional

Diseases [Lehrbuch der Constitutionkrankheiten]. Von Ferdinand

Enke, Stuttgart, 1893.

|

|

23

|

Von Franque O and Geigel A:

Medical-Surgical Monas Booklets [Medicinisch-chirurgische

Monashefte]. Kritisches Sammeljournal fur praktische Heilkunde. Von

Ferdinand Enke, Jahrgang, 1863.

|

|

24

|

Spörlin G: Letter [1627], in Wilhelm

Fabricius Hildanus. In: Works [Opera quæ extant omni]. Johannis

Beyeri, Frankfurt, p601, 1646.

|

|

25

|

Ledelius S: Library of the Medical

Treasure of Practice [Bibliotheca medico-practica sive rerum

medicinarum thesaurus etc.]. Manget JJ (ed). Vol 4. Chouet and

Ritter, Geneva, p592, 1697.

|

|

26

|

Dyer I: A Case of Hematidrosis Combined

with Chromidrosis. The Medical News, Brighton, pp702-703, 1895.

|

|

27

|

Wood JC: A text-book of gynecology.

Boericke and Tafel, Philadelphia, 1894.

|

|

28

|

Virchow RLC: Professor Virchow on Louise

Lateau. The Medical Times and Gazette: A Journal of Medical

Science, Literature, Criticism, and News, p507, 1874.

|

|

29

|

Tittel M: A Case of Hematidrosis. The

Medical Record: A Monthly Journal of Medicine and Surgery, p142,

1876.

|

|

30

|

Chambers TK: A case of bloody sweat.

Lancet. 1:205–209. 1861.

|

|

31

|

Servaes F: About blood sweating on the

head in Dementia paralytica [Ueber Blutschwitzen am Kopfe de

Dementia paralytica]. Centralblatt fur die Medicinischen

Wissenschaften. August Hirschwald, Berlin, 1863.

|

|

32

|

Westphal A: Bloody Sweat [De Sudore

Sanguineo] (Baldinger sylloge t. II). Gryphisw, 1775.

|

|

33

|

Fabre A: Pathogenesis of the

Neuro-Diseases [Les relations pathogéniques des troubles nerveux].

Delahaye, Paris, 1880.

|

|

34

|

Nevis Hyde J: A Practical Treatise On the

Diseases of the Skin. Leo Brothers, Philadelphia, PA, 1893.

|

|

35

|

Anderson M: Lectures on Clinical Medicine.

MacMillan and Co, London, 1877.

|

|

36

|

Berheim S and Laurent E: Practical

Treatise on Clinical and Therapeutic Medicine [Traité Pratique de

Médecine Clinique et Thérapeudique]. Maloine, Paris, 1895.

|

|

37

|

Dechambre A: Encyclopedic Dictionary of

Medical Sciences [Dictionnaire Encyclopédique des Sciences

Médicales]. Asselin & Masson, Paris, 1871.

|

|

38

|

Van Harlingen A: Haematidrosis (Bloody

Sweat). International clinics volume II. Lippincott, Philadelphia,

PA, 1896.

|

|

39

|

Ziegler E: General pathology, The science

of the causes, nature and course of the pathological disturbances

which occur in the living subject. W. Wood and Company, New York,

NY, 1895.

|

|

40

|

Shoemaker JV: Geranium Maculatum in Nelson

E.M. Saint Louis Courier of Medicine Volume XIX. Chambers,

Mississippi, MS, 1888.

|

|

41

|

Kapozi M: Pathology and Treatment of

Diseases of the Skin. W. Wood & Company, New York, NY,

1895.

|

|

42

|

Scott CT: A case of Haematidrosis. Br Med

J. 2993:532–533. 1918.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Holoubek JE and Holoubek AB: Blood, sweat

and fear. A classification of hematidrosis. J Med. 27:115–133.

1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Zheng J, Bian MR, Wu XQ, Xiao Y, Chen YH,

Shen R, Feng C and Gao KB: Hematidrosis: A case report. Dermatol

Ther. 35(e15462)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Alasfoor S, Albashari M, Alsermani A,

Bakir M, Alsermani M and Almustanyir S: A strange occurrence of

hematohidrosis: A case report from Saudi Arabia. Cureus.

14(e21682)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Bhattacharya S, Das MK, Sarkar S and De A:

Hematidrosis. Indian Pediatr. 50:703–704. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Shafique DA, Hickman AW, Thorne A, Elwood

HR and Zlotoff BJ: Pediatric hematidrosis-A case report and review

of the literature and pathogenesis. Pediatr Dermatol. 38:994–1003.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Mora E and Lucas J: Hematidrosis: Blood

sweat. Blood. 121(1493)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Carvalho AC, Machado-Pinto J, Nogueira GC,

Almeida LM and Nunes MB: Hematidrosis: A case report and review of

the literature. Int J Dermatol. 47:1058–1059. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Praveen BK and Vincent J: Hematidrosis and

hemolacria: A case report. Indian J Pediatr. 79:109–111.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Bhagwat PV, Tophakhane RS, Rathod RM,

Shashikumar BM and Naidu V: Hematohidrosis. Indian J Dermatol

Venereol Leprol. 75:317–318. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Varalakshmi B, Doshi VV, Sivalingam D and

Nambi S: The story of a girl with weeping blood: Childhood

depression with a rare presentation. Indian J Psychiatry. 57:88–90.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Talwar M, Chidambaram AC, Mekala S,

Parameswaran N and Delhikumar CG: Haematohidrosis in a 12-year-old

boy: Blood, sweat and tears. Paediatr Int Child Health. 41:300–302.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Hansson K, Johansson EK, Albåge M and

Ballardini N: Paediatric haematohidrosis: An overview of a rare but

clinically distinct condition. Acta Paediatr. 108:1023–1027.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Antunes AS, Peixe B and Guerreiro H:

Hematidrosis, hemolacria, and gastrointestinal bleeding. GE Port J

Gastroenterol. 24:301–304. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Jerajani HR, Jaju B, Phiske MM and Lade N:

Hematohidrosis-a rare clinical phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol.

54:290–292. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Techasatian L, Waraasawapati S,

Jetsrisuparb C and Jetsrisuparb A: Hematidrosis: A report with

histological and biochemical documents. Int J Dermatol. 55:916–918.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Shahgholi E: A case series of

hematohidrosis: A puzzling medical phenomenon. Turk J Pediatr.

60:757–761. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Wang Z, Yu Z, Su J, Cao L, Zhao X, Bai X,

Zhan S, Wu T, Jin L, Zhou P and Ruan C: A case of hematidrosis

successfully treated with propranolol. Am J Clin Dermatol.

11:440–443. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Jafar A and Ahmad A: Child who presented

with facial hematohidrosis compared with published cases. Case Rep

Dermatol Med. 2016(5095781)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Yeşilova Y, Turan E and Aksoy M:

Hematidrosis on the forehead following trauma: A case report. Int J

Dermatol. 56:212–214. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Meyer J, Spacil K, Stehr M, Hinrichs W,

Haller S and Schäfer FM: Hematidrosis after head injury-a case

report. Klin Padiatr. 231:326–327. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Tshifularo M: Blood otorrhea: Blood

stained sweaty ear discharges: Hematohidrosis; four case series

(2001-2013). Am J Otolaryngol. 35:271–273. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Murota H, Kotobuki Y, Yamaga K and

Yoshioka Y: Female child with hematidrosis of the palm: Case report

and published work review. J Dermatol. 47:166–168. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Maglie R and Caproni M: A case of blood

sweating: Hematohidrosis syndrome. CMAJ. 189(E1314)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Barankin B, Alanen K, Ting PT and

Sapijaszko MJA: Bilateral facial apocrine chromhidrosis. J Drugs

Dermatol. 3:184–186. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Nair PA, Kota RKS, Surti NK, Diwan NG and

Gandhi SS: Yellow pseudochromhidrosis in a young female. Indian

Dermatol Online J. 8:42–44. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Jayaraman AR, Kannan P and Jayanthini V:

An interesting case report of hematohidrosis. Indian J Psychol Med.

39:83–85. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Shen H, Wang Z, Wu T, Wang J, Ren C, Chen

H, Yu Z and Don W: Haematidrosis associated with epilepsy in a girl

successfully treated with oxcarbazepine: Case report. J Int Med

Res. 43:263–269. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Uber M, Robl R, Abagge KT, Carvalho VO,

Ehlke PP, Antoniuk SA and Werner B: Hematohidrosis: Insights in the

pathophysiology. Int J Dermatol. 54:e542–e543. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Zhang FK, Zheng YL, Liu JH, Chen HS, Liu

SH, Xu MQ, Nie N and Hao YS: Clinical and laboratory study of a

case of hematidrosis. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 25:147–150.

2004.PubMed/NCBI(In Chinese).

|

|

72

|

Mishra KL: Bloody tears and hematohidrosis

in a patient of PF3 dysfunction: A case report. Cases J.

2(9029)2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Pari T: Hematohidrosis-A rare case. Indian

Dermatol Online J. 10:334–335. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Patel RM and Mahajan S: Hematohidrosis: A

rare clinical entity. Indian Dermatol Online J. 1:30–32.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Favaloro EJ and Lippi G: Commentary:

Controversies in thrombosis and hemostasis part 1-hematidrosis:

‘Blood, Sweat and Fears’ or A ‘Pigment of fertile imaginations?’.

Semin Thromb Hemost. 44:296–297. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Deshpande M, Indla V, Kumar V and Reddy

IR: Child who presented with hematohidrosis (sweating blood) with

oppositional defiant disorder. Indian J Psychiatry. 56:289–291.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Biswas S, Surana T, De A and Nag F: A

curious case of sweating blood. Indian J Dermatol. 58:478–480.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Das D, Kumari P, Poddar A and Laha T:

Bleeding to life: A case series of hematohidrosis and hemolacria.

Indian J Pediatr. 87(84)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Ricci F, Oranges T, Novembre E, Della Bona

ML, la Marca G, de Martino M and Filippi L: Haematohidrosis treated

with propranolol: A case report. Arch Dis Child.

104(171)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Matsuoka R and Tanaka M: Hematidrosis in a

Japanese girl: Treatment with propranolol and psychotherapy.

Pediatr Int. 62:1001–1002. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Tirthani K, Sardana K and Mathachan SR:

Hematohidrosis of the mid-face and hands treated with oral

oxybutynin. Pediatr Dermatol. 38:962–963. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Khalid SR, Maqbool S, Raza N, Mukhtar T,

Ikram A and Qureshi S: Ghost spell or hematohidrosis. J Coll

Physicians Surg Pak. 23:293–294. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Buck AH: A Reference Handbook of the

Medical Sciences Embracing the Entire Range of Scientific and

Allied Sciences. Vol 3. Wood and Company, New York, NY, 1886.

|

|

84

|

Wilks S: Hematidrosis or Bloody Sweat

Complicating Tetanus in Guy's Hospital Reports. Samuel Highley,

London, 1872.

|

|

85

|

Kral F and Novak BJ: Veterinary

Dermatology. Lippincott, Philadelphia, PA, 1953.

|

|

86

|

Liddel Η and Scott R: Grand Lexicon of the

Hellenic Language. Konstantinides, Athens, 1904.

|

|

87

|

Babiniotis G: Lexicon of the New Hellenic

Language, 2nd edition. Lexicology Center, Athens, 2002.

|

|

88

|

Favaloro EJ and Lippi G: Commentary:

Controversies in thrombosis and hemostasis part 1-hematidrosis:

Blood, sweat and fears or a pigment of fertile imaginations? Semin

Thromb Hemost. 44:296–297. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Hoover A, Fustino N, Sparks AO and Rokes

C: Sweating blood: A case series of 2 siblings with hematohidrosis.

J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 43:70–72. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Milne JD: Industrial and Social Position

of Women in the Middle and Lower Ranks. Chapman and Hall, London,

1857.

|

|

91

|

Hou CY, Rutherford R, Chang H, Chang FC,

Shumei L, Chiu CH, Chen PH, Chiang JT, Miao NF, Chuang HY and Tseng

CC: Children's mobile-gaming preferences, online risks, and mental

health. PLoS One. 17(e0278290)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Hashemi S, Ghazanfari F, Ebrahimzadeh F,

Ghavi S and Badrizadeh A: Investigate the relationship between

cell-phone over-use scale with depression, anxiety and stress among

university students. BMC Psychiatry. 22(755)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Conrad LI, Neve M, Nutton V, Porter R and

Wear A: The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge, 1995.

|

|

94

|

Valpy E: The new testament with english

notes, critical, philological and explanatory. Vol 3. 4th edition.

Longman, Baldwin, Whittaker, Rivington and Simpkin, London,

1836.

|

|

95

|

Hesychius: Hesychii Alexandrini Lexicon.

Sumptibus Frederici Maukii, Ienae, 1868.

|

|

96

|

Kechichian E, Khoury E, Richa S and Tomb

R: Religious stigmata: A dermato-psychiatric approach and

differential diagnosis. Int J Dermatol. 57:885–893. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Del Forno C: Stigmata: From Saint Francis

of Assisi to idiopathic. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 141:529–530.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In French).

|

|

98

|

Pilato MM: The memoirs of Dr. Michael

Arthur Creed. Xlibris Corporation, 2010.

|

|

99

|

Jestice PG: Holy People of the World: A

Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO, Santa Barbara & Denver

& Oxford, 2004.

|

|

100

|

Von Gorres JJ: The Stigmata a History of

Various Cases. Richardson, London, 1883.

|