Introduction

Anthrax is a statutory class B infectious disease,

an acute zoonotic infectious disease caused by infection with

Bacillus anthracis (1).

Humans are also susceptible and the main sources of infection are

infected animals and their products, as well as contaminated

environments. Bacillus anthracis infection can occur through

multiple routes, such as the respiratory tract, digestive tract,

skin and mucous membranes (2). The

main clinical type is cutaneous anthrax, while other types include

intestinal anthrax and pulmonary anthrax, which can be secondary to

sepsis and meningitis (3). The

case fatality rate associated with cutaneous anthrax is low;

however, the case fatality rate associated with all other types of

anthrax is high (4). The reported

incidence of anthrax in the Shandong province of China remains low

with 1 case of cutaneous anthrax reported in 2010 and 1 case in

2014. In 2021, there were two cases, and there was a common

exposure history of slaughtering sick cattle. The other epidemic

consisted of 13 cases. The source of infection was sick cattle, and

the route of transmission was slaughtering sick cattle, and being

in contact with contaminated equipment and related cattle products.

The patients were mainly engaged in cattle slaughtering or cattle

product collection and sale-related occupations (5). The present study describes one case

of anthrax meningitis admitted to the Second People's Hospital of

Liaocheng (Linqing, China), and the investigative and treatment

strategies applied are also reported.

Case report

In January 2024, a 55-year-old man was admitted to

The Second People's Hospital of Liaocheng (Linqing, China). The

patient presented with a fever, rapid heart rate, rapid breathing,

high blood pressure, fully unconsciousness, and a tense and painful

facial expression. The patient experienced numb limbs and a stiff

neck. According to the laboratory results and MRI examination

results, the initial diagnosis was encephalitis (considering

bacterial or viral infection), and it was necessary to investigate

the cause of coma and hypertension. Following admission, the

patient received treatment with the dehydration drug mannitol at

0.5 g/kg once every 8 h, an acyclovir injection (5 mg/kg, once

every 12 h) against the cold virus, piperacillin sodium/tazobactam

sodium injection (75 mg/kg, once every 6 h) as resistance against

bacterial infection in the central nervous system (according to

clinical experience), dexamethasone injection (10 mg, once a day)

to reduce brain edema, and tracheal intubation, mechanical

ventilation and sputum aspiration; however, the condition of the

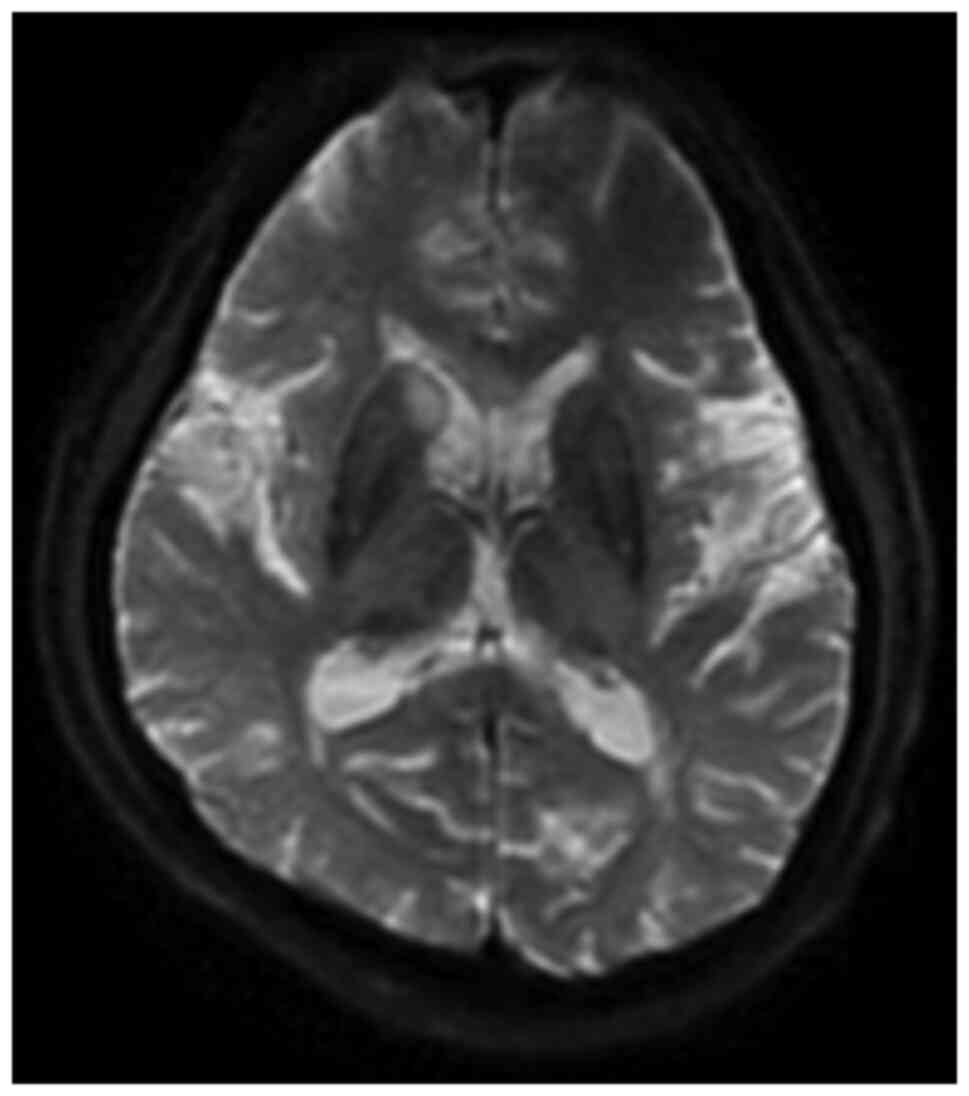

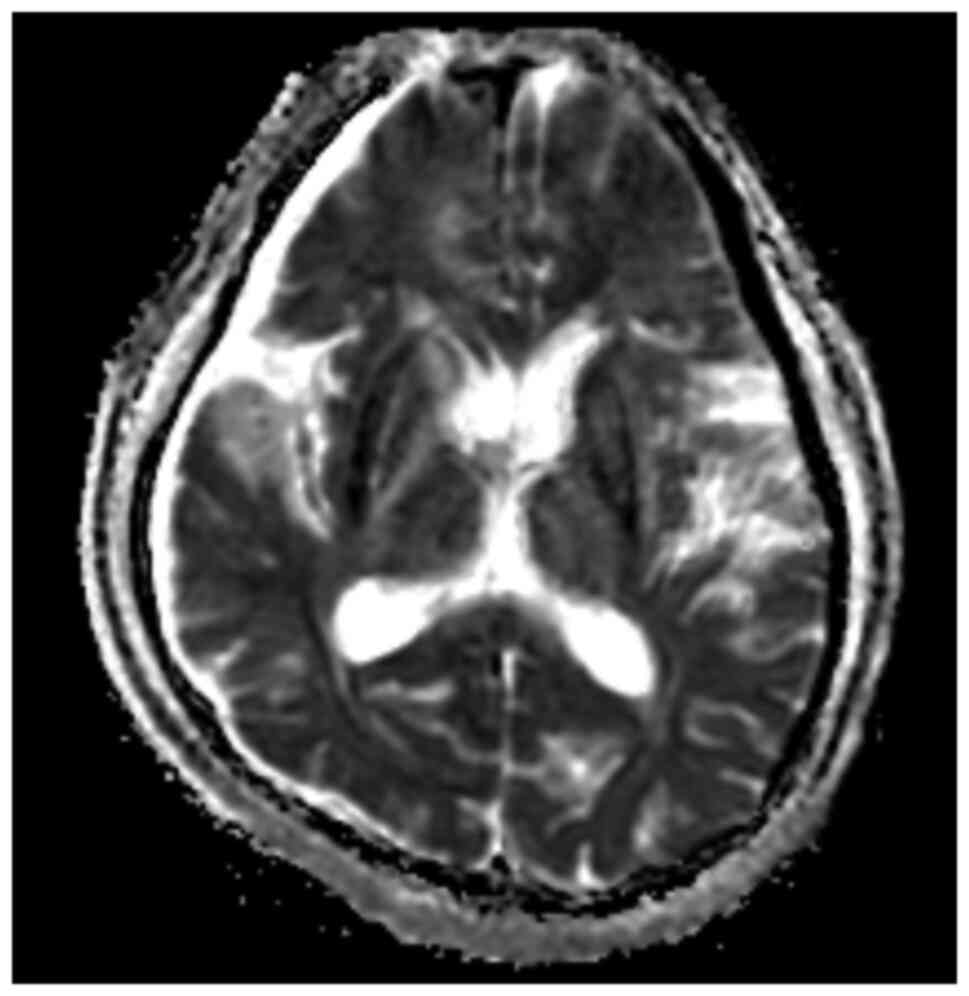

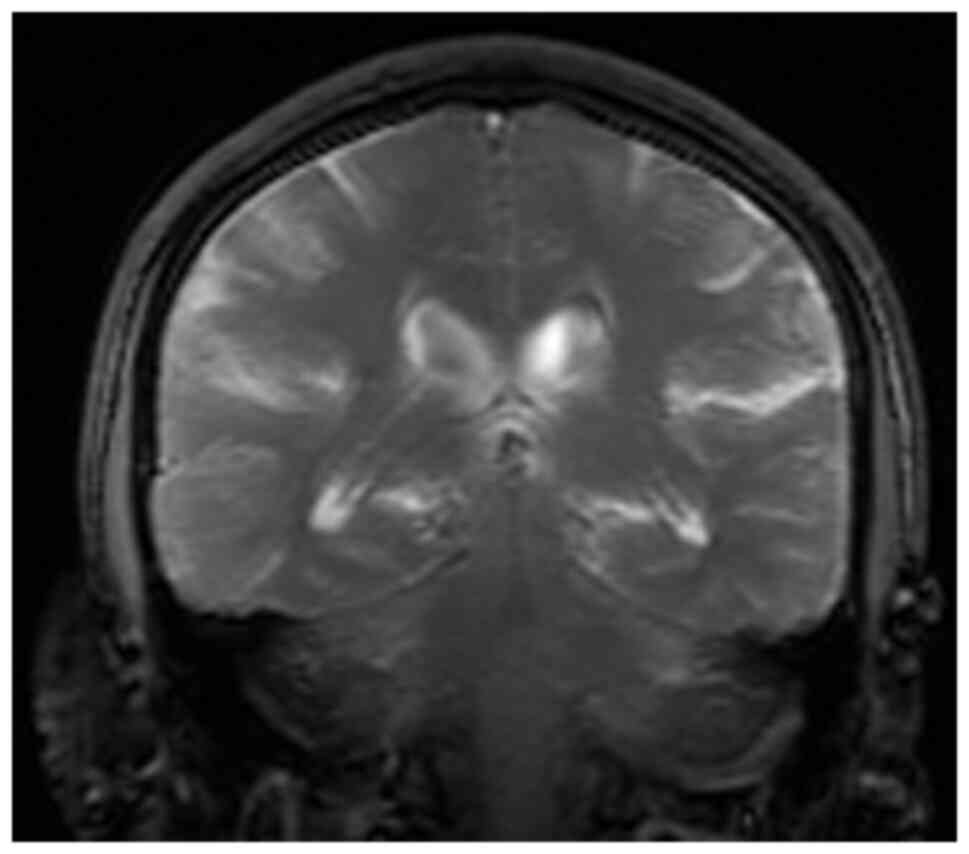

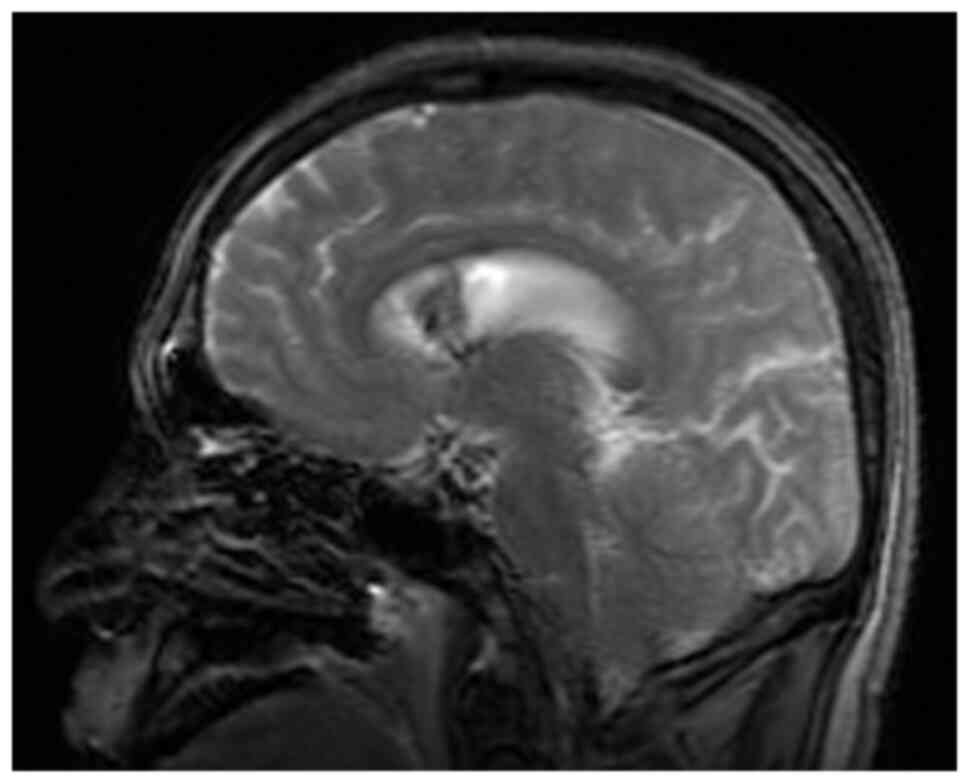

patient did not improve (6). Head

MRI revealed an abnormal signal in the right caudate nucleus and

bilateral hippocampus, indicating encephalitis (Fig. 1, Fig.

2, Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). A brain computed tomography (CT)

scan revealed lacunar infarction (Fig.

5). The MRI findings were consistent with mild cerebral

arteriosclerosis and localized cerebral artery stenosis (7). For ‘bacterial encephalitis’, the

treatment with piperacillin sodium/tazobactam sodium and acyclovir

was terminated, and the more sensitive vancomycin combined with

meropenem was used for anti-infection treatment according to

clinical experience (8).

Cerebrospinal fluid analysis and next generation

sequencing (NGS) of the blood metagenome was performed by Yinfeng

Gene Technology Co., Ltd. A pPathogenic microorganism targeted gene

detection kit was used to prepare DNA/RNA sequencing samples (cat.

no. PT001; Nanjing Practical Medical Inspection Co., Ltd.). The

concentration and purity of DNA and RNA nucleic acids were

determined by Nano-300 micro spectrophotometer (Hangzhou Aosheng

Instrument Co., Ltd.), and the integrity of genomic DNA and genomic

RNA fragments were analyzed by Agilent 2100 biological analyzer

(Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The sequence length was 75 bp and the

direction of sequencing was ‘single end’. The FASTASeq 300

sequencing kit V1.0 (FCH-D SE075-D) (100 cycles; cat. no. S000191;

Shenzhen Zhenmai Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was used. The final

concentration of the library was 3.6 pM. The data were analyzed by

SJ-tNGS software (version 240829; Nanjing Practical Medical

Inspection Co., Ltd.). The results showed Bacillus anthracis

infection. The number of gene detection sequences in the

cerebrospinal fluid was 83,942, and that in the blood was 41. The

diagnosis of anthrax meningitis and anthracemia was made.

In the patient of the present study, anthrax

meningitis was diagnosed and the patient was immediately isolated

in a separate room without contact. At the same time, the

Department of Infectious Diseases and the Center for Disease

Control and Prevention (Liaocheng, China) were contacted to guide

the treatment, and antibiotic treatment was adjusted to vancomycin

+ meropenem + moxifloxacin combined antibacterial therapy,

according to the 2023 version of the anthrax diagnosis and

treatment plan (9), and the

patient was continued to be treated with dehydration, intracranial

pressure reduction, epilepsy prevention and treatment and brain

protection. Tracing the route of infection, the patient went to a

cattle and sheep butcher's shop 12 days ago to buy mutton to eat

himself. Anthrax was detected on the chopping board of the

butcher's shop. The patient had a history of cerebrospinal fluid

rhinorrhea 5 years ago, a recent history of a cold, sneezing and

nasal discharge, and a high possibility of cerebrospinal fluid

rhinorrhea prior to infection. Following combined antibacterial

therapy, the symptoms were alleviated and combined with the

monitoring of blood, cerebrospinal fluid and sputum bacteria, it

was considered that the patient had meningitis directly caused by

anthrax, and meningitis was the main focus. Considering that the

penetration of vancomycin through the blood-brain barrier is poor

(10), treatment was changed to

the protein synthesis inhibitor linezolid, 600 mg by injection,

every 12 h (11), and the

infection indicators of the treated patient exhibited a downward

trend 3 days later. However, it is not necessary to change the

antibacterial drug to linezolid for the treatment of non-meningitis

anthrax. The anthrax test was weakly positive, and the meropenem

treatment was stopped and downgraded to an intravenous drip of

penicillin at 4 million units twice a day. Combined with linezolid,

at 600 mg by injection every 12 h, and moxifloxacin, at 400 mg by

injection, for antibacterial treatment every day, the condition of

the patient markedly improved and the antimicrobial drug was

gradually downgraded in the later 14 days, and the results of the

cerebrospinal fluid analysis were negative. The biochemical results

of the cerebrospinal fluid 33 days after admission showed the

following: Cerebrospinal fluid protein, 682 mg/l (normal range,

150-450 mg/l); cerebrospinal fluid sugar, 3.68 mmol/l (normal

range, 2.5-4.4 mmol/l) and leukocytes, 29x106/l (normal range,

<5x106/l). The results of routine blood tests showed

white blood cell levels of 8.29x109/l (normal range,

4-10x109/l) and a neutrophil ratio of 66.3% (normal

range, 50-70%). Isolation of the patient was terminated following

multidisciplinary consultation. Subsequently, the antibiotic

infusion was gradually discontinued and the treatment was switched

to single oral moxifloxacin tablets. Following standardized

treatment at the hospital, the symptoms of the patient were

markedly alleviated and they were discharged. Follow-up was

performed once every 2 months after discharge, and the patient is

now left with encephalitis sequela, is occasionally fidgety, has

had a seizure once and occasionally has vague consciousness.

Discussion

Anthrax is persistent and after entering the 21st

century, with the development of animal husbandry and the

acceleration of trade circulation, the disease has exhibited an

upward trend in a number of areas, endangering animals and

threatening human health (10). At

present, the diagnosis and treatment of anthrax meningitis still

encounters significant challenges (11). Early detection, diagnosis and

treatment, as well as the prevention of complications can improve

the prognosis of affected patients (12).

With regard to early detection, the anthrax

infection in the present patient may have been caused by a contact

infection from buying mutton. Patients are exposed to lamb meat

with Bacillus anthracis, which may enter the skull through

the nose or external auditory canal and cause encephalitis. In the

patient described herein, although Bacillus anthracis was

not detected in the nasal cavity or external auditory canal of the

patient, the patient's history of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea

and a history of a ‘cold’ suggest that intracranial infection

through the nasal cavity is highly possible. In this case, anthrax

was detected in the cerebrospinal fluid and through blood genetic

monitoring, and the content of Bacillus anthracis in the

cerebrospinal fluid was ample, which led to the diagnosis of

anthrax meningitis. The patient had been examined at the village

clinic in the early stages of infection and had not received a

clear diagnosis, indicating that the local clinicians did not have

sufficient knowledge of anthrax, which led to the worsening

condition of the patient. Therefore, the local government needs to

formulate an intervention plan to carry out comprehensive

intervention measures focusing on health education for animal

husbandry and animal husbandry workers in the county. In addition,

measures are needed to strengthen the training of medical personnel

at all levels in the identification, diagnosis and treatment of

anthrax on the premise of training in the prevention and control of

emerging infectious diseases, so as to improve the ability of early

identification and diagnosis of infectious diseases. Joint

prevention and control mechanisms are required in order to

strengthen the information exchange between health and agriculture

departments, animal husbandry, market supervision and public

security in order to jointly and effectively prevent and control

zoonotic infectious diseases (13). The next step should be to further

strengthen the construction of laboratories and improve the ability

of case diagnoses and environmental monitoring at the grassroots

level.

Early diagnosis and treatment are mandatory. Anthrax

meningitis has a rapid onset, mainly with sudden fever, fatigue,

dizziness, nausea, vomiting, agitation, seizures, delirium and

meningeal irritation (13). The

normal white blood cell count in adult peripheral blood is

4-10x109/l, while that of anthrax patients is increased,

usually at 10-20x109/l, but reaching as high as

60-80x109/l, and is mainly composed of neutrophils

(14). Certain patients have

thrombocytopenia. For an etiological and serological examination,

specimens of blister fluid, blood, cerebrospinal fluid, pleural

effusion and secretions can be collected for testing: i) Bacterial

smear: Under the microscope, gram-positive crude bacilli were

arranged in series (15); ii)

bacterial culture: The collected specimens are inoculated in

nutrient agar medium and Bacillus anthracis can be cultured;

iii) nucleic acid detection: PCR or quantitative PCR detect the

specific nucleic acid of Bacillus anthracis and the results

are positive; iv) antigen detection: Bacillus anthracis

antigen detection can be performed by immunochromatography;

however, a negative result cannot rule out anthrax; v) antibody

detection: ELISA and immunochromatography can detect antibodies to

blood anthrax toxin antigens and capsular antibodies.

The differential diagnosis of anthrax meningitis

includes subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhage, bacterial or

aseptic meningitis and viral encephalitis; MRI, which was applied

in the present case, can easily identify hemorrhagic

meningoencephalitis and subarachnoid or intracerebral hemorrhages

(16). To distinguish between

other hemorrhagic or non-hemorrhagic meningoencephalitis, Gram

staining and cultures of the cerebrospinal fluid (17), which were applied in the present

case, need to be performed. In cases of subarachnoid hemorrhages,

headaches, nausea and vomiting may occur, and meningeal irritation

may be present. Cranial CT scans (18), which were applied in the present

case, or MRI may indicate subarachnoid hemorrhage, and the lumbar

puncture examination of cerebrospinal fluid (19), which was applied in the present

case, may reveal homogeneous bloody cerebrospinal fluid. Epidemic

meningitis is acute purulent meningitis caused by meningococcal

bacteria, and its clinical presentation and cerebrospinal fluid

characteristics are similar to those of anthrax meningitis;

however, it can be distinguished by etiological testing (20). For instance, common bacteria, such

as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli can

also cause bacteremia, and the culture and identification of these

bacteria are essential for the differential diagnosis (21). In addition, knowledge of the

medical and epidemiological history of the patient is also a key

reference for the differential diagnosis. Anthracemia is usually

secondary to severe infections, such as cutaneous, enteral or

pulmonary anthrax; thus, an investigation to identify any possible

history of exposure or medical history can aid doctors in

determining whether a person may be infected with Bacillus

anthracis (22).

Anthrax meningitis should also be differentiated

from rhinosinusal aspergilloma: Common complaints are nasal

congestion, a runny nose and olfactory dysfunction. Unilateral and

persistent headache, trigeminal neuralgia and unilateral scabs are

strong clinical indicators. An endoscopic examination reveals

obvious edema or middle nasal polyps. Imaging reveals unilateral

maxillary-ethmoidal sinus injury with hyperosteogeny, calcification

in the maxillary sinus wall and sinus and obstruction of

bone-phlegm complex. The imaging lesions of aspergilloma include

the dissolution of aspergilloma and the bone wall of the maxillary

sinus, particularly the bone wall of the medial wall, orbital floor

and bone septum. A high-resolution CT scan can emphasize erosion.

An MRI can also be used to describe tumor obstruction secondary to

fluid retention in the sinus cavity. The most common eye and orbit

complications are accompanied by orange peel-like tissue in the

orbital sinus, particularly severe nosebleeds, severe headaches,

possible fever and systemic damage (23).

For anthrax, general treatment includes the

following: Strict isolation, bed rest, appropriate fluid

replacement to maintain water and electrolyte balance in patients

with vomiting, diarrhea and difficulty eating, the appropriate

management of hemorrhage, shock and neurological symptoms, and

hormonal therapy in patients with severe edema or meningitis

(24).

Regarding the treatment of pathogens, Bacillus

anthracis is susceptible to β-lactams (penicillin,

carbapenems), aminoglycosides, macrolides, fluoroquinolones,

tetracyclines, glycopeptides, lincosamides, rifamycins and

oxazolidinones, but not to cephalosporins and sulfonamides

(25). For anthrax with sepsis and

with severe edema, two or more antimicrobial agents active against

Bacillus anthracis should be administered, at least one of

which has bactericidal activity (26). The first-line regimen is

ciprofloxacin and alternative options are levofloxacin,

moxifloxacin, meropenem, imipenem, vancomycin, penicillin G and

ampicillin (27). At least one

other agent is a protein synthesis inhibitor (clindamycin or

linezolid as a first-line regimen; doxycycline or rifampicin as

alternatives) (28). Anthrax

meningitis is treated with at least three antimicrobial agents

active against Bacillus anthracis (29). At least one of them is a fungicide

(fluoroquinolone or β-lactam) and at least one is a protein

synthesis inhibitor; all antimicrobials should have good central

nervous system penetration (30).

Fluoroquinolone antimicrobials include ciprofloxacin [400 mg

intravenously (i.v.) every 8 h] as a first-line option;

levofloxacin (750 mg i.v. once a day) or moxifloxacin (400 mg i.v.

once a day) as alternatives (31).

β-lactam antimicrobials include meropenem (2 g i.v. every 8 h) as a

first-line option; penicillin G (4 million units i.v. every 4 h)

and ampicillin (3 g i.v. every 6 h) are alternatives (32). Protein synthesis inhibitors include

linezolid (600 mg i.v. every 12 h) as a first-line option and

clindamycin (900 mg i.v. every 8 h), vancomycin [60 mg/(kg d),

administered in three divided doses, maintain serum trough

concentration 15-20 mg/l], rifampicin (600 mg i.v. every 12 h) and

chloramphenicol (1 g i.v. every 8-6 h) (33). Due to poor central nervous system

permeability, doxycycline should not be used as a protein synthesis

inhibitor in patients with meningitis (34).

Patients can be discharged after the clinical

symptoms have subsided and their secretions or excretions are

negative for two consecutive bacterial cultures or nucleic acid

tests (24 h apart). Anthrax meningitis has a mortality rate of

almost 100% and is a complication of anthrax exposure. Meningitis

can be primary (i.e., no obvious route of transmission) or

secondary (i.e., complications of any other form of anthrax).

Meningitis occurs in 14-37% of patients infected with anthrax via

injection, ingestion, the systemic cutaneous route or via

inhalation, depending on the route of transmission (3). Therefore, all patients with signs or

symptoms of systemic disease need to be evaluated for meningitis.

In the clinical diagnosis and treatment, the positive rate of

traditional cerebrospinal fluid culture is not high, and the

special flora is not easy to culture, while cerebrospinal fluid

gene detection covers a wide range. In the case of the present

study, no bacteria were detected in the cerebrospinal fluid culture

and the results of cerebrospinal fluid and blood metagenomic

sequencing (NGS) in the early stage revealed infection with

Bacillus anthracis, and pathogen-specific treatment was

administered: Fluoroquinolone antimicrobials, β-lactam

antimicrobials and protein synthesis inhibitors were combined for

antibacterial therapy. The treatment effect was satisfactory and

the anthrax culture was negative; thus, the antimicrobial drug was

gradually tapered and the condition of the patient improved and he

was discharged from the hospital.

In terms of the prevention of epidemics, studies

have shown that the public's awareness of epidemic prevention may

determine the probability of an anthrax epidemic in humans;

strengthening the conveyance of anthrax knowledge may be the key

measure to prevent and control an epidemic (35). It has been suggested that the

health education of farmers and herdsmen on anthrax prevention and

control should be strengthened as soon as possible, so that

herdsmen can develop the hygienic concept and behavior of ‘not

slaughtering, dissecting and not eating sick and dead livestock’

(36). Animal husbandry and

veterinary departments shall strengthen grassroots technical forces

and legal publicity measures, and strengthen the monitoring of

epidemic situations among animals. Immediately following an

outbreak of inter-livestock anthrax, the trading market should be

closed. The dead livestock should be properly handled, such as the

incineration or deep burial of livestock that have died of the

disease, so as to control the spread of the inter-livestock

epidemic as soon as possible, and fundamentally cut off the

transmission route, in order to avoid the occurrence of human

epidemics (37). In this outbreak,

due to the fact that the patient described herein and his family

did not understand the dangers of anthrax and the village doctor

was not highly vigilant, it was not possible to make a positive

diagnosis and perform treatment at an early stage. Therefore,

strengthening the professional knowledge training of county,

township (town) health centers and village doctors, and improving

their clinical diagnosis and treatment capabilities should be the

focus of medical and health work in agricultural and pastoral areas

in the future.

The present case report has certain limitations,

which should be mentioned. First, it only describes one case, and

this disease is known to appear in a number of forms. In addition,

the patient came to the hospital for reexamination regularly, but

the follow-up period after discharge was only 7 months.

In conclusion, anthrax meningoencephalitis is a rare

central nervous system complication of anthrax, which progresses

rapidly following the onset of the disease; timely treatment needs

to be administered in order to prevent the high disability and

mortality rates associated with his type of infection. Early

detection, early diagnosis and early treatment are of particular

importance for patients with anthrax meningoencephalitis and

strengthening epidemic prevention is also a key task. The present

study shares the diagnosis and treatment of a case of anthrax

meningitis with an aim to provide experience and advice regarding

anthrax prevention and treatment.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

KL and LZ conceived and designed the study. ZC and

XY analyzed and summarized the data and wrote the manuscript. KL,

ZC and LZ collected the laboratory examination data and MRI images

of the case. XY critically revised the manuscript. KL and LZ

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the

principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

The patient involved in the present study was

subjected to standard clinical practice and provided written

informed consent for the publication of medical data and

images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Tschopp R and Kidanu AG:

Knowledge-attitude and practice of Anthrax and brucellosis:

Implications for zoonotic disease surveillance and control in

pastoral communities of Afar and Somali region, Ethiopia. PLoS Negl

Trop Dis. 18(e0012067)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Nana SD, Caffin JH, Duboz R,

Antoine-Moussiaux N, Binot A, Diagbouga PS, Hendrikx P and Bordier

M: Towards an integrated surveillance of zoonotic diseases in

Burkina Faso: The case of anthrax. BMC Public Health.

22(1535)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bradley JS, Bulitta JB, Cook R, Yu PA,

Iwamoto C, Hesse EM, Chaney D, Yu Y, Kennedy JL, Sue D, et al:

Central nervous system antimicrobial exposure and proposed dosing

for anthrax meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 78:1451–1457.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Blackburn JK, Kenu E, Asiedu-Bekoe F,

Sarkodie B, Kracalik IT, Bower WA, Stoddard RA and Traxler RM: High

case-fatality rate for human anthrax, Northern Ghana, 2005-2016.

Emerg Infect Dis. 27:1216–1219. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhang EM, Zhang HJ, He JR, Li W and Wei

JC: Analysis of epidemic characteristics of anthrax in China from

2017 to 2019 and molecular typing of Bacillus anthracis. Zhonghua

Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 56:422–426. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

6

|

Caffes N, Hendricks K, Bradley JS,

Twenhafel NA and Simard JM: Anthrax meningoencephalitis and

intracranial hemorrhage. Clin Infect Dis. 75 (Suppl 3):S451–S458.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Zhou G, Wang H, Zhang X, Yu L, Yao F, Li B

and Fang Q: Cerebral arteriosclerosis stenosis predicts poor

short-term prognosis in non-valvular atrial fibrillation related

cardioembolic stroke treated by reperfusion therapy. Clin Neurol

Neurosurg. 207(106738)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gozdas HT, Dogan A, Wright H and Fox-Lewis

A: Laboratory findings in acute bacterial meningitis and acute

viral encephalitis. N Z Med J. 137:103–104. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Bhattacharya D, Kshatri JS, Choudhary HR,

Parai D, Shandilya J, Mansingh A, Pattnaik M, Mishra K, Padhi SP,

Padhi A and Pati S: One Health approach for elimination of human

anthrax in a tribal district of Odisha: Study protocol. PLoS One.

16(e0251041)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhang H, Zhang E, Guo M, He J, Li W and

Wei J: Epidemiological characteristics of human Anthrax - China,

2018-2021. China CDC Wkly. 4:783–787. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kutmanova A, Zholdoshev S, Roguski KM,

Sholpanbay Uulu M, Person MK, Cook R, Bugrysheva J, Nadol P,

Buranchieva A, Imanbaeva L, et al: Risk factors for severe

cutaneous anthrax in a retrospective case series and use of a

clinical algorithm to identify likely meningitis and evaluate

treatment outcomes, kyrgyz republic, 2005-2012. Clin Infect Dis. 75

(Suppl 3):S478–S486. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Thompson JM, Cook R, Person MK, Negrón ME,

Traxler RM, Bower WA and Hendricks K: Risk factors for death or

meningitis in adults hospitalized for cutaneous anthrax, 1950-2018:

A systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 75 (Suppl 3):S459–S467.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Sidwa T, Salzer JS, Traxler R, Swaney E,

Sims ML, Bradshaw P, O'Sullivan BJ, Parker K, Waldrup KA, Bower WA

and Hendricks K: Control and Prevention of Anthrax, Texas, USA,

2019. Emerg Infect Dis. 26:2815–2824. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Ben-Shmuel A, Glinert I, Sittner A,

Bar-David E, Schlomovitz J, Levy H and Weiss S: Doxycycline,

levofloxacin, and moxifloxacin are superior to ciprofloxacin in

treating anthrax meningitis in rabbits and NHP. Antimicrob Agents

Chemother: Apr 30, 2024 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

15

|

Wicky PH, Poiraud J, Alves M, Patrier J,

d'Humières C, Lê M, Kramer L, de Montmollin É, Massias L,

Armand-Lefèvre L and Timsit JF: Cefiderocol treatment for severe

infections due to difficult-to-treat-resistant non-fermentative

Gram-Negative Bacilli in ICU patients: A case series and narrative

literature review. Antibiotics (Basel). 12(991)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Zhou ZM, Gu LL, Zhou ZY and Liang QL:

Recent Advance of S100B proteins in spontaneous intracerebral

hemorrhage and aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Front Biosci

(Landmark Ed). 29(37)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Bobinger T, Roeder SS, Spruegel MI,

Froehlich K, Beuscher VD, Hoelter P, Lücking H, Corbeil D and

Huttner HB: Variation of membrane particle-bound CD133 in

cerebrospinal fluid of patients with subarachnoid and intracerebral

hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 134:600–607. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zhao X, Zhou B, Luo Y, Chen L, Zhu L,

Chang S, Fang X and Yao Z: CT-based deep learning model for

predicting hospital discharge outcome in spontaneous intracerebral

hemorrhage. Eur Radiol. 34:4417–4426. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Conklin J and Lev MH: Beyond the AJR:

Intracranial CTA versus lumbar puncture for suspected subarachnoid

hemorrhage with negative head CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol: Jul 17, 2024

(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

20

|

Li JH, Wu D, Yin ZD and Li YX: Analysis of

epidemic characteristics for meningococcal meningitis in China

during 2015-2017. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 53:159–163.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

21

|

Bita Fouda AA, Latt A, Sinayoko A,

Mboussou FFR, Pezzoli L, Fernandez K, Lingani C, Miwanda B, Bulemfu

D, Baelongandi F, et al: The bacterial meningitis epidemic in

banalia in the democratic republic of congo in 2021. Vaccines

(Basel). 12(461)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zhai LN, Zhao Y, Song XL, Qin TT, Zhang

ZJ, Wang JZ, Sui CY, Zhang LL, Lv M, Hu LF, et al: Inhalable

vaccine of bacterial culture supernatant extract mediates

protection against fatal pulmonary anthrax. Emerg Microbes Infect.

12(2191741)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Vrinceanu D, Dumitru M, Patrascu OM,

Costache A, Papacocea T and Cergan R: Current diagnosis and

treatment of rhinosinusal aspergilloma (Review). Exp Ther Med.

22(1264)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Beliveau M, Rubets I, Bojan D, Hall C,

Toth D, Kodihalli S and Kammanadiminti S: Animal-to-Human dose

translation of ANTHRASIL for treatment of inhalational anthrax in

healthy adults, obese adults, and pediatric subjects. Clin

Pharmacol Ther. 115:248–255. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Doganay M, Dinc G, Kutmanova A and Baillie

L: Human Anthrax: Update of the diagnosis and treatment.

Diagnostics. 13(1056)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Person MK, Cook R, Bradley JS, Hupert N,

Bower WA and Hendricks K: Systematic review of hospital treatment

outcomes for naturally acquired and bioterrorism-related anthrax,

1880-2018. Clin Infect Dis. 75 (Suppl 3):S392–S401. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Bower WA, Yu Y, Person MK, Parker CM,

Kennedy JL, Sue D, Hesse EM, Cook R, Bradley J, Bulitta JB, et al:

CDC guidelines for the prevention and treatment of anthrax, 2023.

MMWR Recomm Rep. 72:1–47. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Matharoo K, Chua J, Park JR, Ingavale S,

Jelacic TM, Jurkouich KM, Compton JR, Meinig JM, Chabot D,

Friedlander AM and Legler PM: Engineering an Fc-Fusion of a capsule

degrading enzyme for the treatment of anthrax. ACS Infect Dis.

8:2133–2148. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lin C, Dou X, Zhang D, Sun Y, Han H, Chen

C, Zhang X, Li S, Chen Y, Zhang H, et al: Epidemiological

Investigation of an Inhalational Anthrax Patient Traveling for

Medical Treatment in Beijing Municipality, China, August 2021.

China Cdc Wkly. 4:4–7. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Hesse EM, Godfred-Cato S and Bower WA:

Antitoxin use in the prevention and treatment of anthrax disease: A

systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 75 (Suppl 3):S432–S440.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Aktories K: Treatment of ovarian cancer

with modified anthrax toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

119(e2210179119)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Martchenko Shilman M, Bartolo G, Alameh S,

Peterson JW, Lawrence WS, Peel JE, Sivasubramani SK, Beasley DWC,

Cote CK, Demons ST, et al: In vivo activity of repurposed

amodiaquine as a host-targeting therapy for the treatment of

anthrax. ACS Infect Dis. 7:2176–2191. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Legler PM, Little SF, Senft J, Schokman R,

Carra JH, Compton JR, Chabot D, Tobery S, Fetterer DP, Siegel JB,

et al: Treatment of experimental anthrax with pegylated circularly

permuted capsule depolymerase. Sci Transl Med.

13(eabh1682)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Jauro S, Ndumnego OC, Ellis C, Buys A,

Beyer W and Heerden HV: Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a

non-living anthrax vaccine versus a live spore vaccine with

simultaneous penicillin-G treatment in cattle. Vaccines (Basel).

8(595)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Oh J, Jo H, Park J, Lee H, Kim HJ, Lee H,

Kang J, Hwang J, Woo S, Son Y, et al: Global burden of

vaccine-associated rheumatic diseases and their related vaccines,

1967-2023: A comprehensive analysis of the international

pharmacovigilance database. Int J Rheum Dis.

27(e15294)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Schneider SN, Nguyen TQ, Hake KL,

Nightingale BS, Mangan TP, Rice AN and Carroll JC: Development of a

pharmacy point-of-dispensing toolkit for anthrax post-exposure

prophylaxis for allegheny county postal workers. J Public Health

Manag Pract. 30:231–239. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Li S, Ma Q, Chen H, Liu Y, Yao G, Tang G

and Wang D: Epidemiological investigation and etiological analysis

of a cutaneous anthrax epidemic caused by Butchering Sick Cattle in

Guizhou, China. Front Public Health. 8(65)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|