Introduction

Kartagener syndrome (KS) is a rare autosomal

recessive genetic disorder. In 1933, Kartagener linked visceral

inversion, sinusitis and bronchiectasis as independent syndromes

(1). In 1976, Pedersen et

al (2) proposed that owing to

the congenital lack of axial arms in the cilia throughout the body,

there is a loss of motility, resulting in the retention of

secretions and pathogens. This condition predisposes individuals to

recurrent bronchiectasis and sinus lesions in the long term. In

1981, Sleigh (3) found that cilia

were not completely immobile but exhibited abnormal movement, which

was termed primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD). PCD accompanied by

visceral reversal is known as KS, and ~50% of patients with PCD

have KS. KS is frequently accompanied by chronic respiratory

symptoms, and when it worsens, it is easily misdiagnosed as an

infection. In addition, atypical early imaging can easily lead to

missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of pulmonary malignant tumors.

The present study reports a rare clinical case of KS complicated by

small-cell lung cancer, which was initially misdiagnosed as a lung

infection owing to atypical clinical symptoms and imaging findings.

After a precise diagnosis, the patient was ultimately diagnosed

with KS and received timely treatment. It is hoped that this case

will draw the attention of clinical respiratory physicians to KS

combined with lung cancer.

Case presentation

A 66-year-old male patient with a history of smoking

(the patient smoked 20 cigarettes per day x 40 years, and thus he

had a smoking index of 800), exhibited primary symptoms of cough,

chest pain and intermittent fever for 4 months, admitted to the

Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine of Jining No. 1

People's Hospital (Jining, China). Despite having received

intermittent antibiotics for a lung infection at a local hospital,

the patient's symptoms failed to improve and the chest pain

worsened. Physical examination revealed normal vital signs, coarse

breathing sounds in both lungs, and no dry or wet rales or pleural

friction sounds. On percussion, the boundary of the cardiac

dullness widened to the right and no pathological murmurs were

heard. Laboratory tests revealed a normal white blood cell count

(5.63x109/l; normal range, 4-10x109/l),

normal neutrophil levels (3.94x109/l; normal range,

2.04-7.5x109/l), a normal procalcitonin level (0.05

ng/ml; normal range, 0-0.05 ng/ml), an elevated neuron-specific

enolase level (48.96 ng/ml; normal range, 0-16.3 ng/ml) and an

elevated carcinoembryonic antigen level (13.52 ng/ml; normal range,

0-5 ng/ml), as well as normal liver and kidney function, blood

lipids and blood glucose. Electrocardiography showed a right-sided

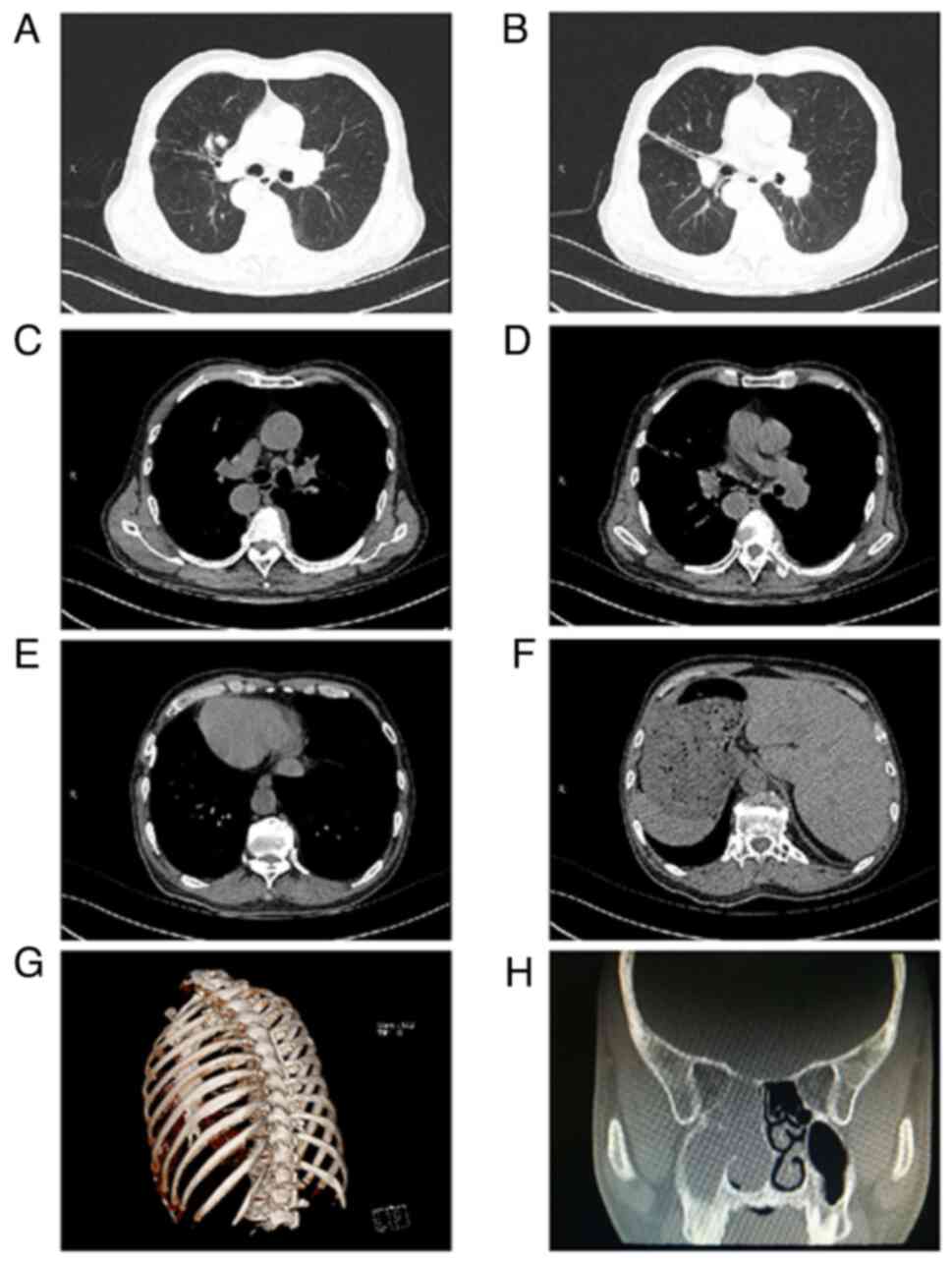

heart. Chest CT + 3D reconstruction of the ribs revealed chronic

inflammation of both lungs, multiple bronchiectasis in both lungs,

nodules in the upper lobe of the right lung, a flaky high-density

shadow in the right main bronchus, bilateral pleural thickening,

localized calcification of the right pleura and a right-sided heart

with transposition of thoracic and abdominal organs (Fig. 1A-G). Paranasal sinus CT revealed

right maxillary sinusitis, ethmoid sinus, nasal soft tissue shadow,

polyps, deviated nasal septum, and bilateral middle and lower

turbinate hypertrophy (Fig. 1H).

The patient presented with right locus coeruleus, visceral

inversion, sinusitis and bronchial dilatation and was diagnosed

with KS. Clinical consideration of the patient as having KS,

combined with the patient's previous long-term smoking history and

the presence of a flaky hyperdense shadow in the right main

bronchus, did not exclude the possibility of bronchial phlegm

embolism, foreign body or obstruction. Bronchoscopy revealed normal

bronchial tubes in the right lung. A polypoid neoplasm was observed

in the opening of the upper lobe of the left lung, incompletely

obstructing the lumen and spreading along the middle segment to the

opening of the middle and lower lobes of the left lung, with

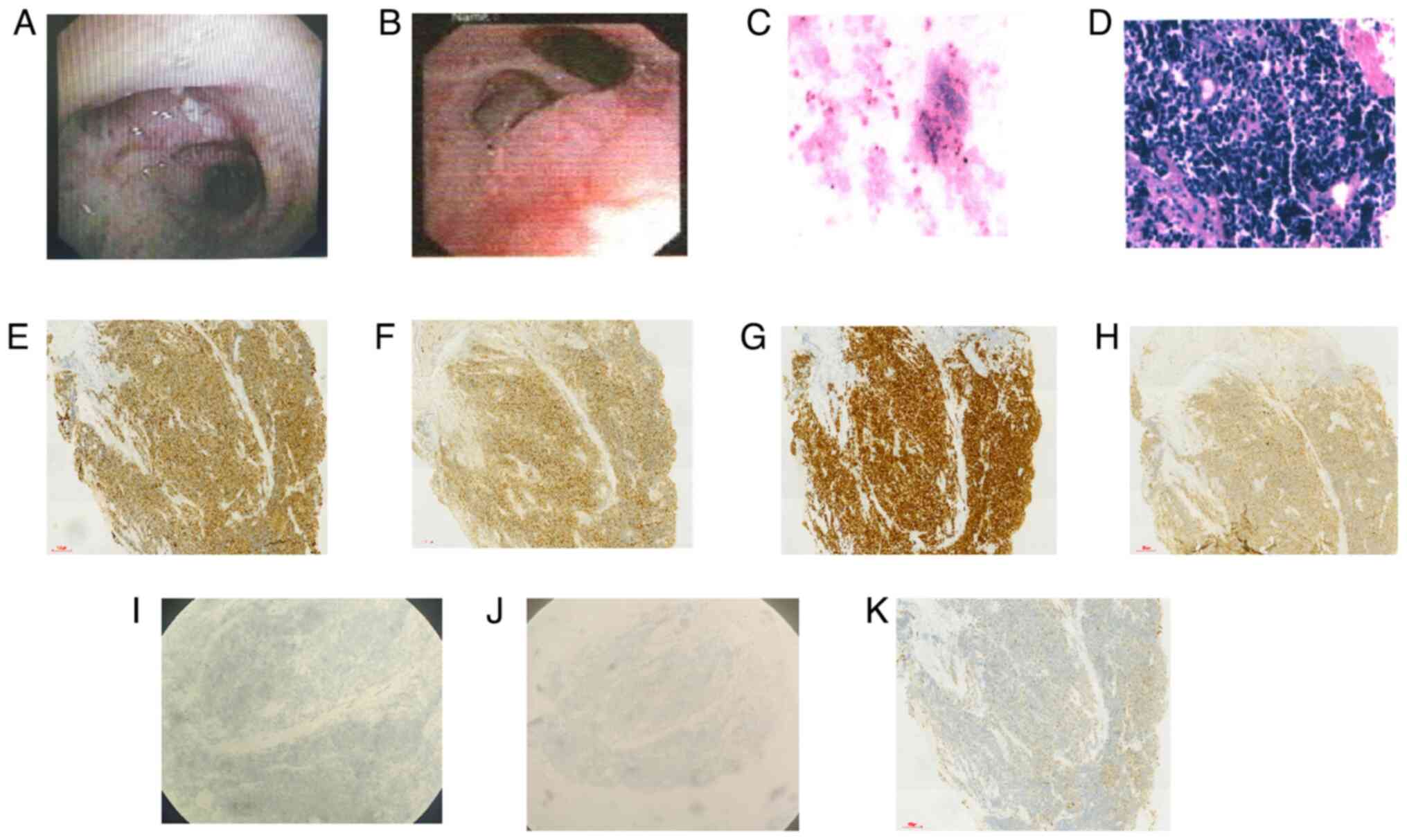

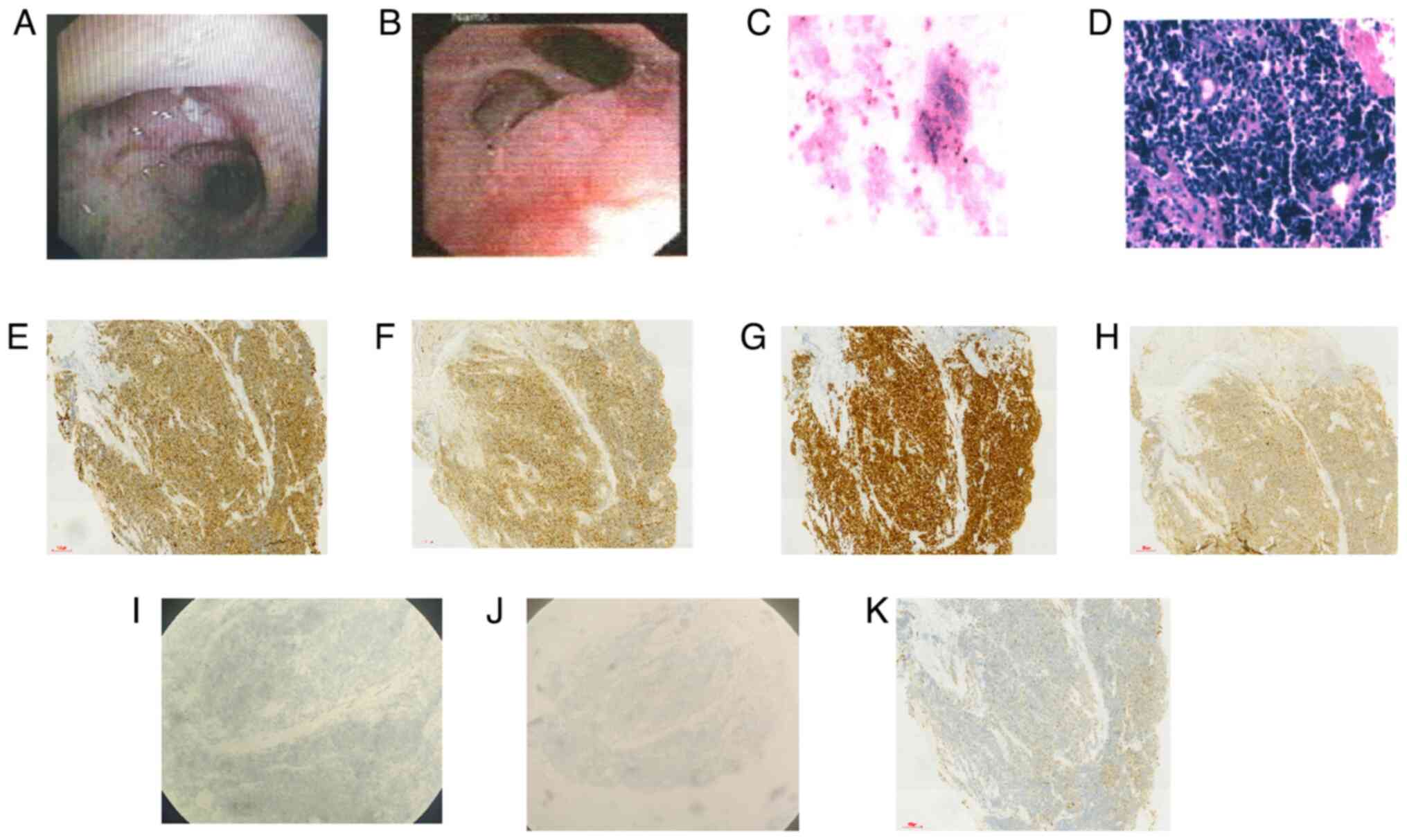

necrosis on the surface, which was biopsied (Fig. 2A and B). Pathological and immunohistochemical

analysis was performed in the Department of Pathology, Jining NO. 1

People's Hospital. The specimens were fixed in 10% neutral

formalin, with conventional paraffin embedding, and sliced into

4-µm thick continuous sections. Light microscopy was used for

observation. Hematoxylin (5 min) and eosin (2 min) staining of the

pathological specimens was performed at room temperature. At the

same time, the EnVision two-step method of immunohistochemistry was

used according to standard protocols, with antibodies for

cytokeratin 7 (CK7; cat. no. Kit-0021), CD56 (cat. no. R-0148-03),

thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1; cat. no. MAB-0599),

synaptophysin (Syn; cat. no. R-0482-03), chromogranin A (CgA; cat.

no. RMA-0548), aspartic peptidase A, (NapsinA; cat. no. MAB-0704)

and lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (LCK; cat. no.

R-0347-03) (all pre-diluted; Fuzhou Maixin and Shanghai Changdao

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) The secondary antibody was from the

Universal DAB Detection Kit [cat. no. 760-500; Roche Diagnostics

(Shanghai) Co., Ltd.], which was a universal type. Cancer cells

were detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and H&E

stain revealed heterogeneous epithelioid cells with dense cells,

deeply stained nuclei and little cytoplasm. Immunohistochemistry

revealed CK7(+), CD56(+), TTF-1(+), Syn(+), CgA(-), NapsinA(-) and

LCK(+) results, confirming the diagnosis of small cell lung cancer

(Fig. 2C-K). A complete

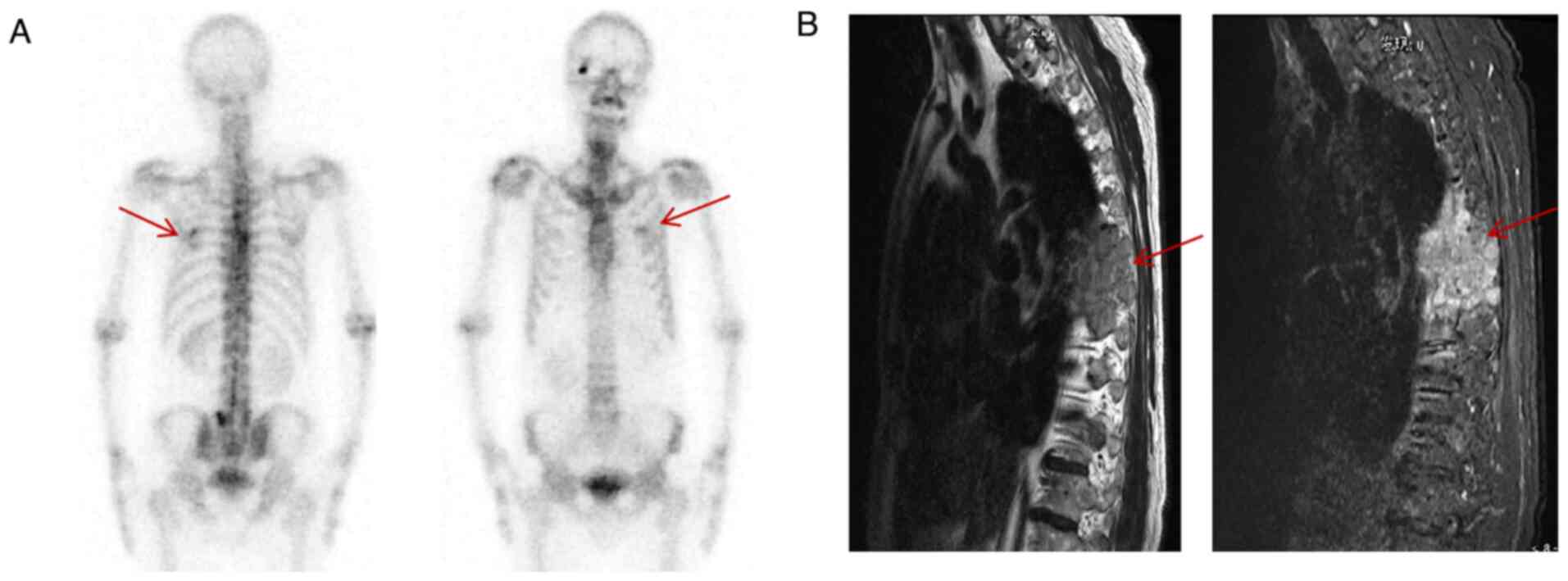

extrapulmonary auxiliary examination suggested bone metastasis

(Fig. 3A, B). Therefore, the following diagnoses

were made: i) Small cell lung cancer of the left lung (extensive

stage) and ii) KS. Small cell lung cancer is the most malignant

type of lung cancer, is incurable and combination chemotherapy can

only control the disease temporarily; the cancer will eventually

progress (4). The patient had an

ECOG performance status score (5)

of 1, and according to the Chinese Primary Lung Cancer Diagnostic

and Treatment Guidelines (6), the

patient received a cisplatin/etoposide combination chemotherapy for

6 cycles and bisphosphonates treatment; the disease was controlled

and the patient was rated as being in partial remission after the

treatment according to Solid Tumor Response Assessment Criteria

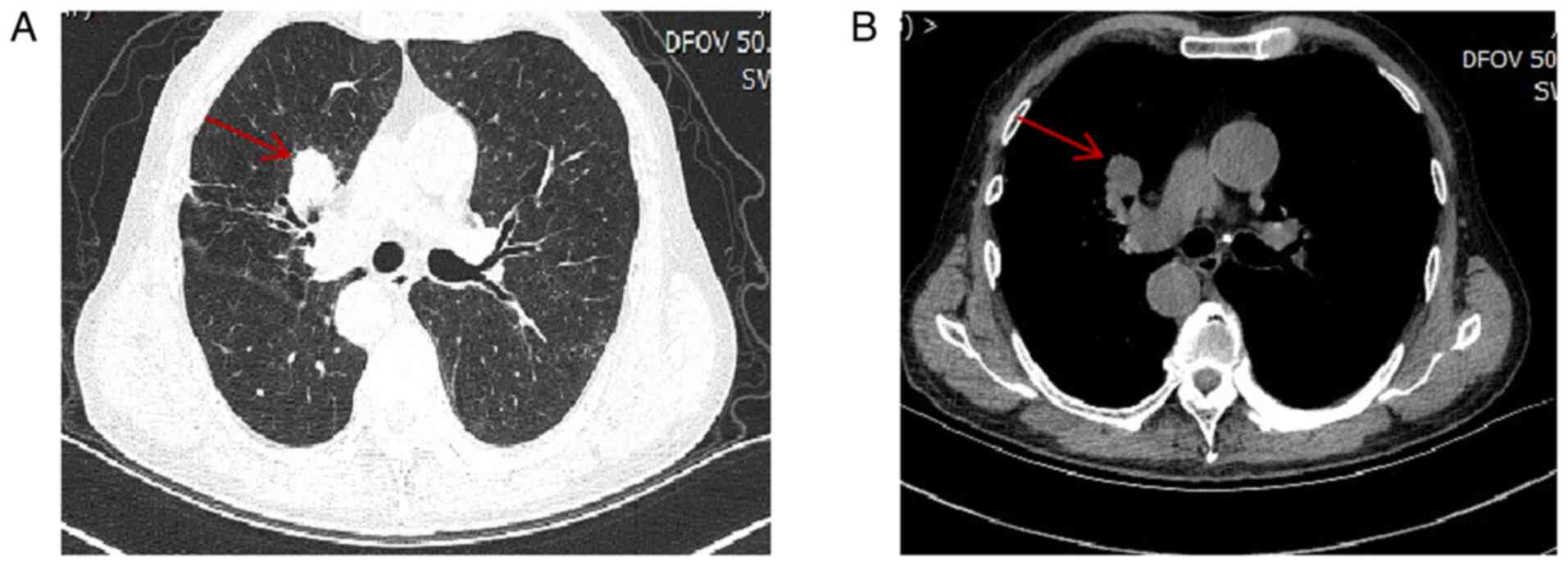

(7). However, half a year later,

the patient's disease had progressed (Fig. 4), and the patient's family refused

to continue the antitumor treatment due to side effects and

financial concerns, and chose symptomatic supportive therapy

instead. Through telephone follow-ups, it was revealed that the

patient eventually passed away 1 year later owing to the

progression of lung cancer.

| Figure 2Bronchoscopy clarified the pathology.

(A) Polypoid neoplasm seen in the opening of the upper lobe of the

left lung. (B) The neoplasm spreading along the mid-section to the

opening of the middle and lower lobes of the left lung. (C) Cancer

cells were detected in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid by HE

staining (magnification, x200); (D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining

revealed heterogeneous epithelioid cells with dense cells, deeply

stained nuclei and little cytoplasm, denoting small cell lung

cancer (magnification, x200). Immunohistochemistry staining for (E)

cytokeratin 7(+), (F) CD56(+), (G) thyroid transcription

factor-1(+), (H) synaptophysin(+), (I) chromogranin A(-), (J)

aspartic peptidase A(-) and (K) lymphocyte-specific protein

tyrosine kinase(+) (magnification, x100). |

Discussion

The patient was clinically suspected of having KS

owing to recurrent cough, sputum production and fever, symptoms

commonly attributed to infectious factors. However, the

exacerbation of chest pain prompted admission to our hospital for

further evaluation. Based on the clinical symptoms, the following

differential diagnoses were considered: Pulmonary embolism,

myocardial infarction, tension pneumothorax and aortic coarctation.

3D reconstruction of the ribs was performed with the aim of

excluding fractures and other conditions. However, upon chest CT

examination, small nodules and hyperdense shadows were observed in

the patient's airways, suggesting the possibility of sputum

embolus, foreign bodies and possible lung cancer. The patient

lacked the typical pathognomonic features of lung cancer and no

obvious mass on CT. The patient's condition progressed despite

anti-infective treatment and the patient developed chest pain. This

was different from the previously reported cases (8-10),

and therefore, it is required to reconsider whether there was a

combination of other diseases on the basis of KS. Thus, the

patient's chest CT was repeatedly scrutinized and slight

irregularities in the left bronchial wall, partial stenosis and

characteristic wave-like changes were found. Therefore, it was

deemed necessary to perform a bronchoscopy, revealing an

abnormality in the left bronchus and a tissue biopsy was taken.

Finally, pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of small

cell lung cancer. The patient's chest pain was attributed to a

combination of small cell lung cancer and rib metastasis.

In conclusion, KS is typically characterized by

recurrent respiratory infections. The present case highlights the

importance of prompt action when anti-infective treatments do not

yield satisfactory results in clinical settings and CT scans do not

fully explain clinical symptoms, particularly in heavy smokers.

Intensified examinations, including bronchoscopy, should be

promptly pursued. This case serves as a reminder of the need for

timely diagnosis of KS combined with small cell lung cancer,

offering valuable guidance for clinical practice.

A literature review was then performed. KS is a

subset of PCD, a rare autosomal recessive genetic disease with an

incidence of ~ 1 in 30,000 (11,12).

The pathogenesis of KS is not fully understood, but several studies

have shown that the majority of causative mutations involve two

genes, DNA H5 and DNAI1(13).

Typical clinical manifestations include visceral transposition,

bronchiectasis and chronic infectious sinusitis. Patients with KS

may present with respiratory symptoms since early childhood, with

recurrent fever, cough, sputum and blood in the sputum. The right

heart and visceral transposition do not usually cause significant

clinical symptoms. Imaging is the primary method used to confirm

the diagnosis of KS. CT examination of the chest and abdomen can

reveal visceral inversion and bronchial dilatation and determine

whether they are combined with infection; additionally, CT of the

sinus can identify sinus lesions. Treatment mainly focuses on

preventing respiratory infections, including the use of antibiotics

and pulmonary physiotherapy to prevent complications (12,14).

KS is not associated with age, sex or smoking

history (11,12), whereas lung cancer, especially

squamous lung cancer, is more common in older adults, men and

smokers. There are limited reports on KS combined with small-cell

lung cancer. In KS, the congenital absence of axial arms of the

cilia lead to loss of mobility, causing the retention of secretions

and pathogens, dysfunction of airway clearance, long-term

stimulation of pathogenic microorganisms, chronic inflammation, and

long-term and repeated exposure to chronic carcinogens, which

ultimately result in the development of lung cancer (8-10).

This is the main factor in lung cancer development reported in the

previous literature. In the present case, the patient was at high

risk of developing lung cancer due to being an elderly male and

having a long history of smoking, which, combined with the presence

of KS, likely contributed to the development of lung cancer.

However, the exact effects of KS on tumorigenesis require further

investigation. For the patient in this case study, respiratory

infection symptoms were the primary concern, leading to ongoing

anti-infective treatment. Owing to the prominence of these

symptoms, the clinical signs of lung cancer were not obvious,

potentially resulting in delayed diagnosis. Furthermore, small cell

lung cancer is highly malignant, and despite a timely diagnosis,

the prognosis of the patient in this case was poor, with the

patient surviving only 1 year after diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This research was supported by the Key R&D Program

of Jining (grant no. 2023YXNS243) and the Medical System Staff

Science and Technology Innovation Program Project of Shandong

(grant no. SDYWZGKCJHLH2023068).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JZ, LW and CQ contributed to the conception and

design of the study. Data collection and analysis were performed by

CB, JM and LH. The manuscript was written by JZ and CB. CQ confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved

the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

As the patient had passed away when the case report

was prepared, written informed consent was obtained from the

patient's daughter for the publication of potentially identifying

images or data included in this article.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Kartagener M: Zur Pathogenese der

Bronchiedtasien. I. Mitte lung Bron chiektasien bei Situs viscerum

inversus. Beitr Klin Tuberk. 83:489–501. 1933.

|

|

2

|

Pedersen H and Mygind N: Absence of

axonemal arms in nasal mucosa cilia in Kartagener's syndrome.

Nature. 5:494–495. 1976.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Sleigh MA: Ciliary function in mucus

transport. Chest. 80 (Suppl 6):S791–S795. 1981.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Torre LA, Siegel RL and Jemal A: Lung

cancer statistics. Adv Exp Med Biol. 893:1–19. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Schnipper LE, Davidson NE, Wollins DS,

Tyne C, Blayney DW, Blum D, Dicker AP, Ganz PA, Hoverman JR,

Langdon R, et al: American Society of Clinical Oncology Statement:

A conceptual framework to assess the value of cancer treatment

options. J Clin Oncol. 33:2563–2577. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhi X, Shi Y and Yu J: Standards for the

diagnosis and treatment of primary lung cancer (2015 version) in

China. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 37:67–78. 2015.PubMed/NCBI(In Chinese).

|

|

7

|

Schwartz LH, Litière S, de Vries E, Ford

R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, Shankar L, Bogaerts J, Chen A, Dancey J,

et al: RECIST 1.1-update and clarification: From the RECIST

committee. Eur J Cancer. 62:132–137. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Horie M, Arai H, Noguchi S, Suzuki M,

Sakamoto Y and Oka T: Kartagener syndrome with lung cancer and

mediastinal tumor. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 48:375–378.

2010.PubMed/NCBI(In Japanese).

|

|

9

|

Zhou D, Tian Y, Lu Y and Yang X:

Anatomical variants of pulmonary segments and uni-portal

thoracoscopic segmentectomy for lung cancer in a patient with

Kartagener syndrome: A case report. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg.

69:1432–1437. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhang J, Xiao Y, Bai M and Bian J: A rare

case of Kartagener syndrome combined with lung cancer. Asian J

Surg. 46:4801–4802. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ibrahim R and Daood H: Kartagener

syndrome: A case report. Can J Respir Ther. 57:44–48.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tadesse A, Alemu H, Silamsaw M and

Gebrewold Y: Kartagener's syndrome: A case report. J Med Case Rep.

12(5)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Pandey AK, Maithani T and Bhardwaj A:

Kartagener's syndrome: A clinical reappraisal with two case

reports. Egypt J Ear Nose Throat Allied Sci. 15:271–274. 2014.

|

|

14

|

Flume PA, O'Sullivan BP, Robinson KA, Goss

CH, Mogayzel PJ Jr, Willey-Courand DB, Bujan J, Finder J, Lester M,

Quittell L, et al: Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: Chronic

medications for maintenance of lung health. Am J Respir Crit Care

Med. 176:957–969. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|