Introduction

Hypoxic pulmonary hypertension (HPH) is an important

pathophysiological process and plays a key role in the development

of a variety of pulmonary diseases, including chronic obstructive

pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary heart

disease. Multiple pathogenic pathways have been implicated in the

development of HPH, including those at the molecular and genetic

levels of smooth muscle and endothelial cells and adventitia. The

HPH ‘phenotype’ is characterized by a decreased ratio of

apoptosis/proliferation in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells

(PASMCs) and a thickened, disordered adventitia (1). The increased proliferation and

reduced apoptosis of PASMCs is a component of pulmonary

hypertension, increased pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary

arterial pressure, which is associated with COPD and right

ventricular failure (2). Since

the proliferation of SMCs is an essential feature of vascular

proliferative disorders, considerable efforts have been made to

develop a therapeutic strategy that effectively suppresses SMC

proliferation.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ)

agonists act as negative regulators of SMC growth (3). They are potent inhibitors of

vascular SMC proliferation in vitro and in vivo

(3). PPARγ agonists can stimulate

the production and secretion of apolipoprotein E (ApoE), which has

anti-proliferative effects on human PASMCs (4). Nisbet et al (5) found that rosiglitazone (a PPARγ

agonist) attenuated hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodelling

and hypertension by suppressing oxidative and proliferative

signals. These studies provide the mechanisms underlying the

therapeutic effects of PPARγ activation in pulmonary

hypertension.

Studies have also suggested that PPARγ agonists

upregulate phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome

10 (PTEN) expression in allergen-induced asthmatic lungs (6). Zhang et al (7) demonstrated that rosiglitazone

inhibits the migration of human hepatocellular BEL-7404 cells by

upregulating PTEN. The tumor suppressor gene, PTEN, encodes a

dual-specificity phosphatase that recognizes protein and

phosphatidylinositol substrates and modulates cellular functions,

such as migration and proliferation. However, the role of PPARγ in

regulating PTEN expression in PASMCs under hypoxic conditions has

not yet been elucidated. Therefore, the present study aimed to

examine the molecular mechanisms through which PPARγ activation

modulates PTEN expression in PASMCs under hypoxic conditions, since

hypoxia is a proliferative stimulator of PASMCs (5).

In the present study, we investigated the effects of

troglitazone (a PPARγ agonist) on PTEN gene expression and the

apoptosis of PASMCs under hypoxic conditions. We found that

troglitazone increased PTEN expression in PASMCs in a

concentration-dependent manner and increased the apoptosis of

PASMCs under hypoxic conditions.

Materials and methods

Cell culture of PASMCs

Human PASMCs were purchased from ScienCell Research

Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The PASMCs were cultured and

expanded in SMC growth medium (GM): smooth muscle cell basal medium

(BM; ScienCell Research Laboratories) supplemented with SMC growth

supplement (ScienCell Research Laboratories), 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). The cells were

cultured at 37ºC in a 5% CO2 incubator, and the cell

culture medium was changed every 2 days. Cells were regularly

passaged every 4–5 days.

Hypoxia treatment

The PASMCs were cultured under hypoxic conditions in

order to determine the anti-proliferative effects of troglitazone

on PASMCs. A hypoxic environment for PASMC culture was created in

an incubator: 5% CO2+94% N2+1% O2.

The cells were collected for gene and protein expression

experiments after 72 h. Generally, the PASMCs were seeded in plates

in BM overnight before being used in the experiments.

PASMC culture with PTEN inhibitor or

PPARγ antagonist

The PASMCs were seeded at 1×104

cells/well in a 12-well plate and cultured in GM supplemented with

2.5 μM dipotassium

bisperoxo(5-hydroxypyridine-2-carboxyl)oxovanadate (V)

[bpV(HOpic)], a PTEN inhibitor, or 1 μM

2-chloro-5-nitro-N-phenylbenzamide (GW9662), a PPARγ antagonist

(both were purchased from EMD4Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany).

bpV(HOpic) and GW9662 were added to the cell culture medium 1 h

prior to the addition of troglitazone. The PASMCs were cultured in

an incubator under hypoxic conditions for 72 h. Cell proliferation

was determined using the CyQUANT® Cell Proliferation

assay kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Proteins were extracted

from the treated cells using PhosphoSafe™ Extraction Reagent (EMD

Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Following quantification, the

proteins were used for western blot analysis.

Quantitative reverse transcription PCR

(qRT-PCR) analysis

PASMCs were analyzed by qRT-PCR to determine gene

expression at 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 24 h after treatment with

troglitazone. Total RNA was isolated as previously described

(8). DNase I was used to remove

DNA contamination. cDNA was synthesized using the

Maxima® First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas,

Hanover, MD, USA).

To quantify gene expression levels,

Maxima® SYBR-Green qPCR Master Mix (2X) (Fermentas) was

used. The qPCR thermal cycling protocol was programmed for 40

cycles: 1 cycle of initial denaturation for 10 min, then

denaturation at 95ºC for 15 sec, annealing for 30 sec and extension

at 72ºC for 30 sec. The primers used are listed in Table I.

| Table IPrimers used for RT-PCR. |

Table I

Primers used for RT-PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence | Annealing temp.

(ºC) | Size (bp) |

|---|

| GAPDH | Forward

5′-AGCCACATCGCTCAGACAC-3′

Reverse 5′-TAAAAGCAGCCCTGGTGAC-3′ | 60 | 90 |

| PTEN | Forward

5′-TCACCAACTGAAGTGGCTAAAGA-3′

Reverse 5′-CTCCATTCCCCTAACCCGA-3′ | 60 | 155 |

| AKT-1 | Forward

5′-TAACCTTTCCGCTGTCGC-3′

Reverse 5′-ATGTTGTAAAAAAACGCCG-3′ | 58 | 125 |

| AKT-2 | Forward

5′-GGTCGCCAACAGCCTCAA-3′

Reverse 5′-CACTTTAGCCCGTGCCTTG-3′ | 58 | 127 |

Cell proliferation

PASMC proliferation was determined using the

CyQUANT® Cell Proliferation assay kit (Invitrogen).

Briefly, 1×104 PASMCs/well were seeded into 24-well

plates and cultured with BM for 24 h. The cell culture medium was

changed to GM supplemented with various concentrations of

troglitazone (stock solution 20 mM in 100% DMSO) for 72 h in an

incubator under hypoxic conditions at 37ºC. Subsequently, the cell

culture supernatant was removed. The cells were washed with PBS and

frozen at −80ºC for 1 h. Each well was then incubated with 200 μl

CyQUANT® cell-lysis buffer containing DNase-free RNase

(1.35 U/ml) for 1 h at room temperature to eliminate the RNA

component of the fluorescence signal. Subsequently, 200 μl

cell-lysis buffer containing 2X solution of CyQUANT® GR

dye were added to each well for 10 min. The fluorescence intensity

was measured using a Tecan fluorescence microplate reader (Tecan

Infinite M200 microplate reader; LabX, Canada) with 480 nm

excitation and 520 nm emission.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release for

cytotoxic determination

The cytotoxicity of troglitazone towards PASMCs was

determined using CytoTox-ONE™ Homogeneous Membrane Integrity assay

(Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Briefly, 5×104 PASMCs/well

were cultured in a 12-well plate with GM supplemented with

troglitazone for 72 h under normoxic conditions at 37ºC.

Subsequently, cell culture supernatant was collected and mixed with

CytoTox-ONE™ Reagent for 20 min. After the addition of stop

solution, the fluorescence signal was measured at an excitation

wavelength of 560 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm.

Western blot analysis of PASMCs

Protein expression in the treated and non-treated

PASMCs was determined by western blot analysis as previously

described (9). Cells were lysed

with PhosphoSafe™ Extraction Reagent (EMD Millipore) and the

protein concentration was determined using Bradford reagent

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Proteins were separated and electrophoretically

blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After washing with 10 mM

Tris/HCl wash buffer (pH 7.6) containing 0.05% Tween-20, the

membrane was incubated in blocking buffer (5% non-fat dry milk, 10

mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) for 3 h at room

temperature. Subsequently, the blots were incubated with diluted

primary antibodies: AKT (1:1,000), phosphorylated (Ser 473) AKT

(p-AKT) (1:500), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)

(1:1,000) and PTEN (1:200) (all purchased from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4ºC.

Subsequently, anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with HRP (dilution,

1:3,000–1:8,000) was used to detect the binding of antibodies. The

binding of the specific antibody was visualized using the

SuperSignal Chemiluminescent Substrate kit and exposed to X-ray

film (both from Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL, USA).

Apoptosis assay

Proteins from the treated and non-treated PASMCs

were used to determine the apoptosis of PASMCs by determining the

activities of caspase-3, -8 and -9.

Caspase-3 and -8 activities were determined using

caspase-3 and -8 assay kits, Fluorimetric (Sigma-Aldrich, Sigma,

St. Louis, MO, USA). The fluorescence intensity of caspase-3 was

recorded at a wavelength of 360 nm for excitation and a wavelength

of 460 nm for emission, and that of caspase-8 was recorded at an

excitation of 360 nm and an emission of 440 nm. The activity of

caspase was calculated as fluorescence intensity (FI)/min/ml =

ΔFlt/(t × v), where ΔFlt is the difference in fluorescence

intensity between time zero and time t minutes; t is the reaction

time in min; and v is the volume of the sample in ml.

Similarly, caspase-9 activity was determined using

the caspase-9 assay kit, Fluorimetric (QIA72; EMD4Biosciences). The

fluorescence intensity was recorded at a wavelength of 400 nm for

excitation and a wavelength of 505 nm for emission. The same

formula as the one used for the calculation of caspase-3 activity

was used to calculate caspase-9 activity.

TUNEL assay

To detect the apoptosis of PASMCs following

treatment with troglitazone, the PASMCs were cultured in BM and

incubated for 72 h under hypoxic conditions. TUNEL assay was

performed using the In situ Cell Death Detection kit (Roche)

as per the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, the cells were

fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at 25ºC. After washing

with PBS for 30 min, the cells were incubated in permeabilization

solution (0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium citrate) for 10 min at

4ºC. After washing, the cells were incubated with rabbit

anti-calponin antibody overnight at 4ºC. On the second day,

reaction mixture from the kit supplemented with goat anti-rabbit

IgG conjugated with FITC was applied to the cells for 1 h at 37ºC

in the dark. The samples were counterstained with DAPI to visualize

the nuclei after TUNEL staining. The apoptotic index was calculated

as TUNEL+ cells/total cells/low magnification field.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

software (version 10.0). All experiments were performed at least 3

times. The data are presented as the means ± standard error means

(SEM) and analyzed with the method of analysis of variance (ANOVA)

using the Bonferroni test. A Student's t-test was performed to

determine statistical difference. All tests were performed with a

significance level of 5%.

Results

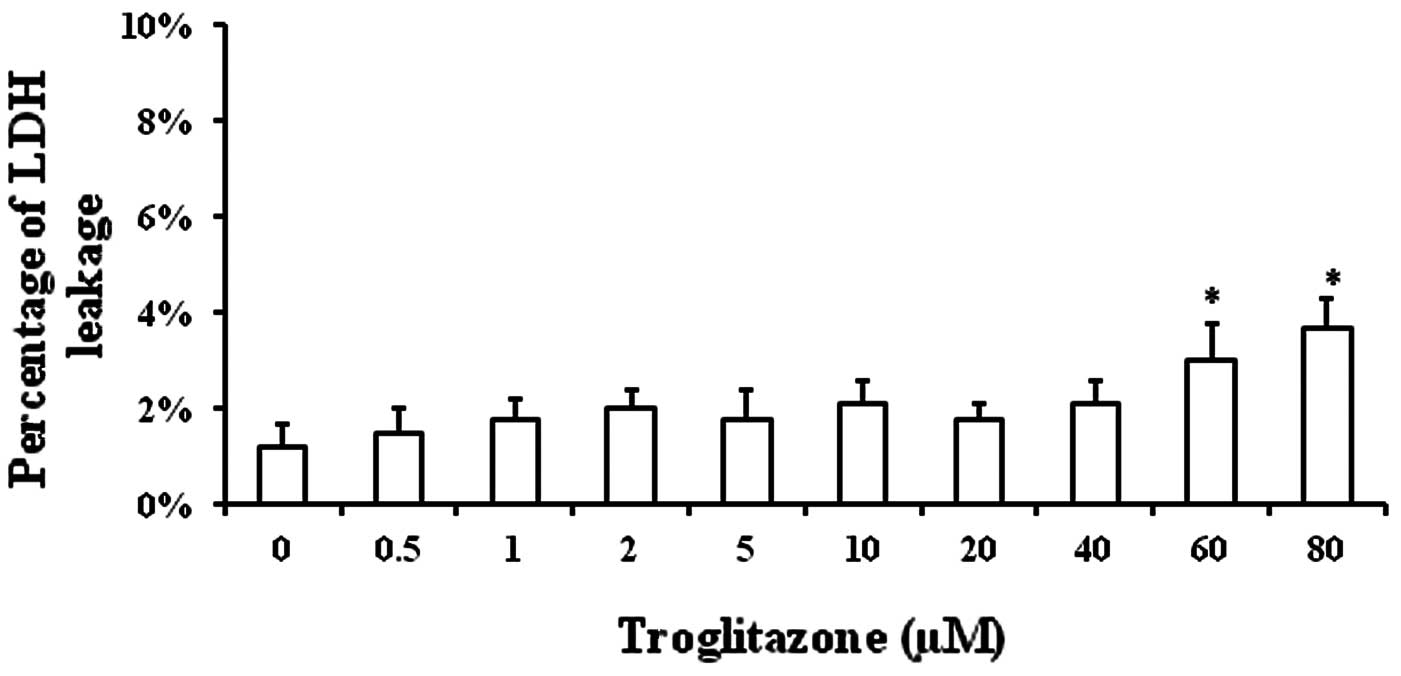

Toxicity of troglitazone towards

PASMCs

The toxicity of troglitazone towards the cells was

determined in order to exclude the possibility that the decrease in

PASMC proliferation was due to the toxicity of troglitazone towards

PASMCs. PASMCs were cultured in GM supplemented with troglitazone

for 48 h in an incubator under normal conditions. The supernatant

was collected to measure LDH concentration (an index of cell

injury). Significant cell injury was only observed when the

troglitazone concentration was increased up to 60 and 80 μM

(Fig. 1).

The percentage of LDH in the supernatant was

1.2±0.5% when the cells were cultured in GM without troglitazone,

while it was 1.5±0.5% with 0.5 μM troglitazone, 1.8±0.4% with 1 μM,

2±0.4% with 2 μM, 1.8±0.6% with 5 μM, 2.1±0.5% with 10 μM, 1.8±0.3%

with 20 μM, 2.1±0.5% with 40 μM, 3±0.8% with 60 μM and 3.7±0.6%

with 80 μM troglitazone (Fig. 1).

These results demonstrated that troglitazone was well tolerated by

PASMCs.

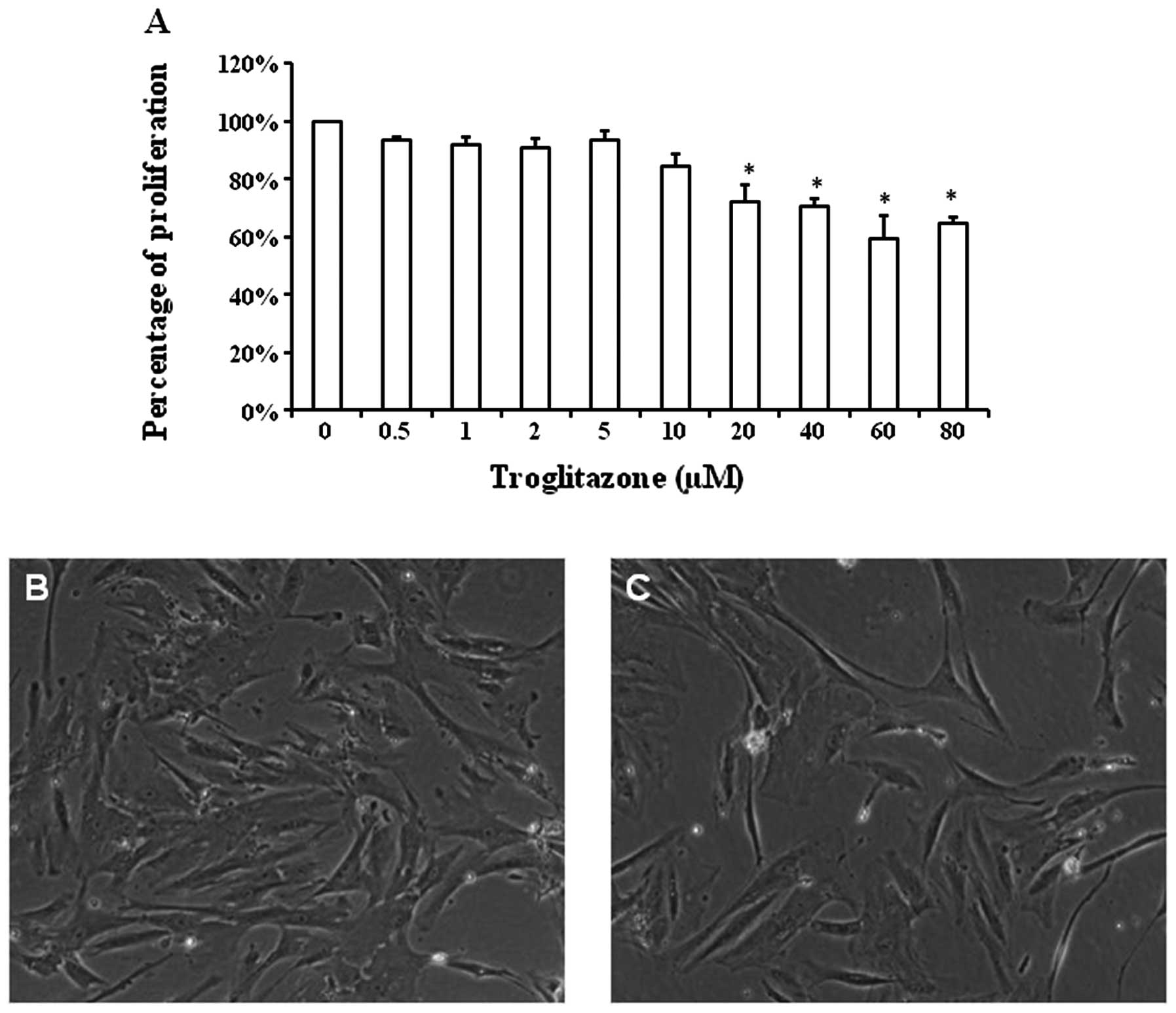

Concentration-dependent effects of

troglitazone on PASMC proliferation

The proliferation rate of the PASMCs was altered in

a concentration-dependent manner by troglitazone in the cells

cultured in GM under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 2A). The cell number of PASMCs

treated with 0.5 μM troglitazone was reduced to 93.3±1.2% compared

with that of the PASMCs not treated with troglitazone (considered

as 100%). The percentage cell number of PASMCs cultured with

troglitazone was 91±2.7% with 1 μM of troglitazone, 91.1±3.5% with

2 μM, 93.5±2.8% with 5 μM, 84.3±4.2 with 10 μM, 72±5.8% with 20 μM,

70.4±3% with 40 μM, 59.3±8.3% with 60 μM and 64.6±2.1% with 80 μM

troglitazone. Starting at the concentratikno of 20 μM, troglitazone

significantly reduced the proliferation of PASMCs under hypoxic

conditions (P<0.05).

Typical images of PASMC density following culture in

GM with or without troglitazone are shown in Fig. 2B and C. Starting at the

concentration of 20 μM, troglitazone significantly reduced the

PASMC proliferation rate. Thus, we selected the concentration of 20

μM troglitazone for the remaining experiments.

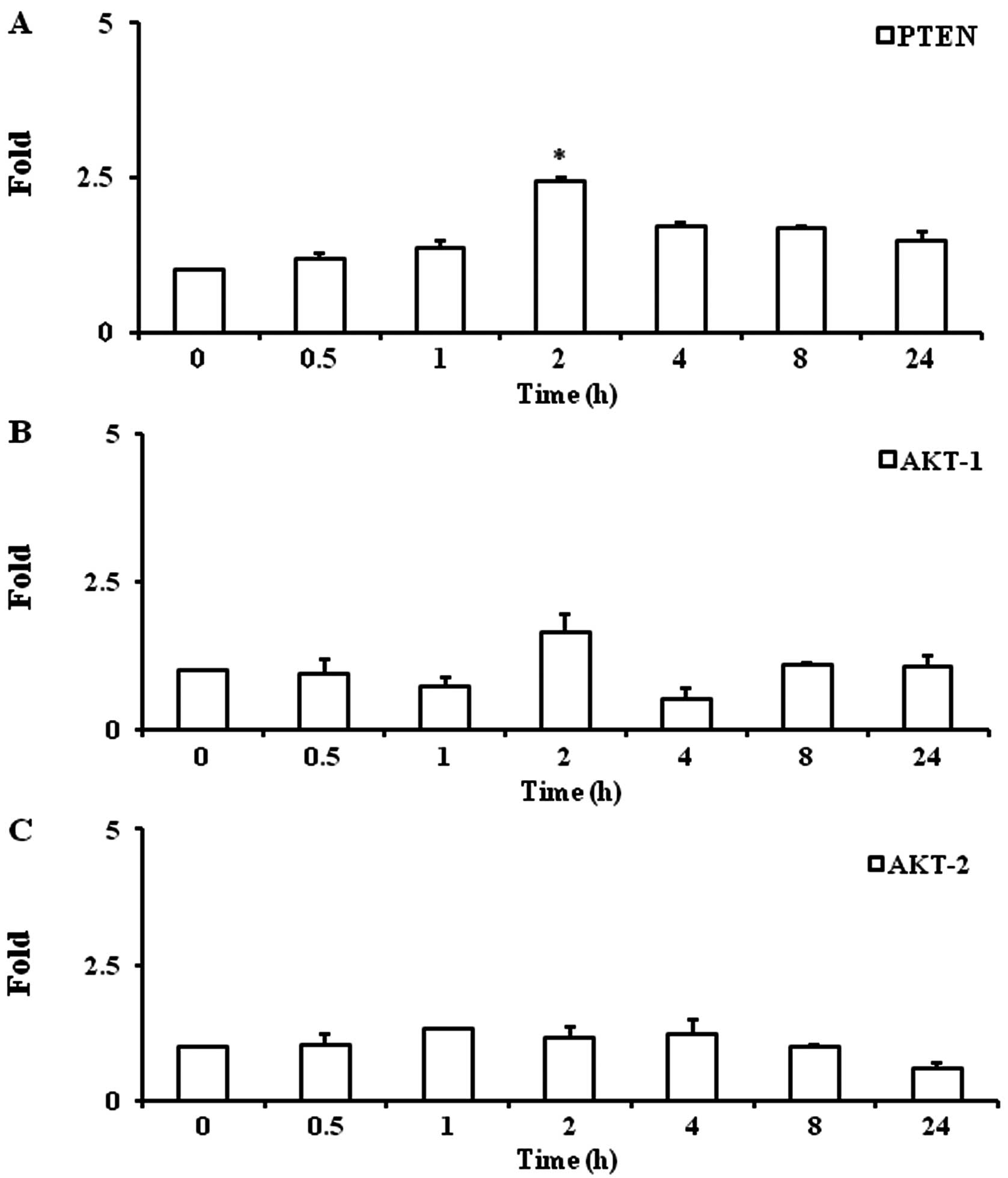

Troglitazone increases PTEN gene

expression

Troglitazone significantly increased PTEN gene

expression by 2.4±0.1-fold at 2 h as compared with the baseline

levels (P<0.05) under hypoxic conditions. Upregulated PTEN gene

expression was maintained up to 8 h (1.7±0.02-fold, P<0.05)

(Fig. 3A).

Troglitazone does not alter gene

expression of AKT-1 and AKT-2

Troglitazone did not significantly alter the gene

expression of AKT-1 and AKT-2 in the PASMCs between any 2 time

points (Fig. 3B and C).

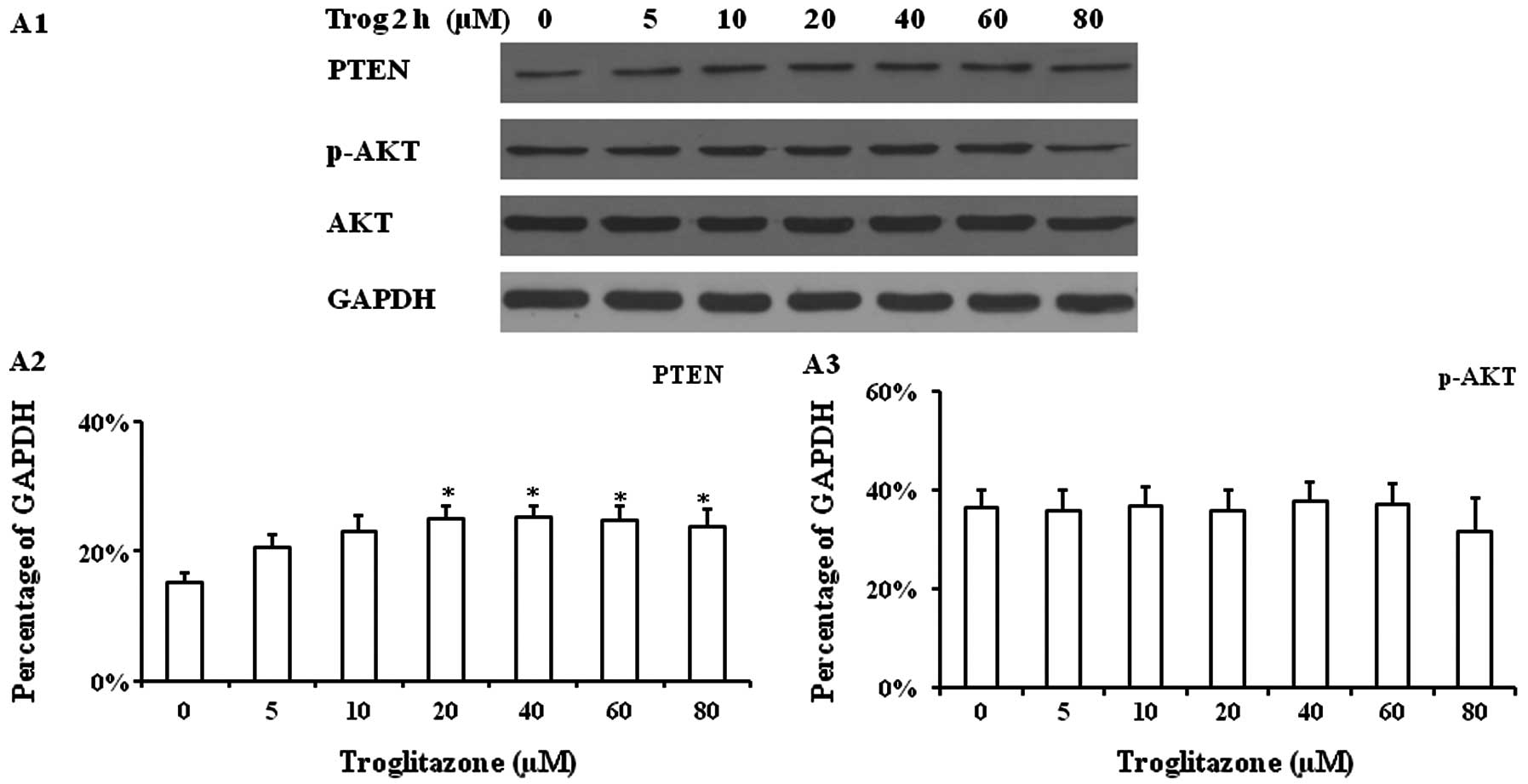

Western blot analysis of cultured PASMCs

supplemented with troglitazone

Troglitazone increased PTEN protein expression in

PASMCs cultured under hypoxic conditions for 2 h. A significantly

increased PTEN protein expression level was observed when the cells

were treated with troglitazone at concentrations between 20–80 μM,

while no significant changes in p-AKT and AKT expression were

observed (Fig. 4A). The PASMCs

were then cultured with 20 μM troglitazone for 24 h and

DMSO-treated cells (without troglitazone) were used as controls,

since troglitazone was diluted in DMSO. In the cells treated with

troglitazone, a significantly increased PTEN protein expression was

observed within 2 h compared with the cells treated with DMSO

alone. The highest PTEN protein expression level was observed

within 4 h after the addition of troglitazone, which was

significantly higher than that at 0.5 h (Fig. 4B). Troglitazone also progressively

reduced p-AKT expression within 2 h; these levels were

significantly lower than those from the cells treated with DMSO

alone.

To determine whether the upregulated PTEN protein

expression induced by troglitazone was mediated by the PPARγ

signaling pathway and inhibited by the PTEN inhibitor, PASMCs were

pre-treated with 2.5 μM bpV(HOpic) (a PTEN inhibitor) or 1 μM

GW9662 (PPARγ antagonist) for 1 h prior to the addition of

troglitazone. It was found that the upregulated protein expression

of PTEN was reduced by pre-treatment with bpV(HOpic) and GW9662 for

up to 24 h (Fig. 4C and D).

Effects of bpV(HOpic) and GW9662 on

proliferation of PASMCs treated with troglitazone

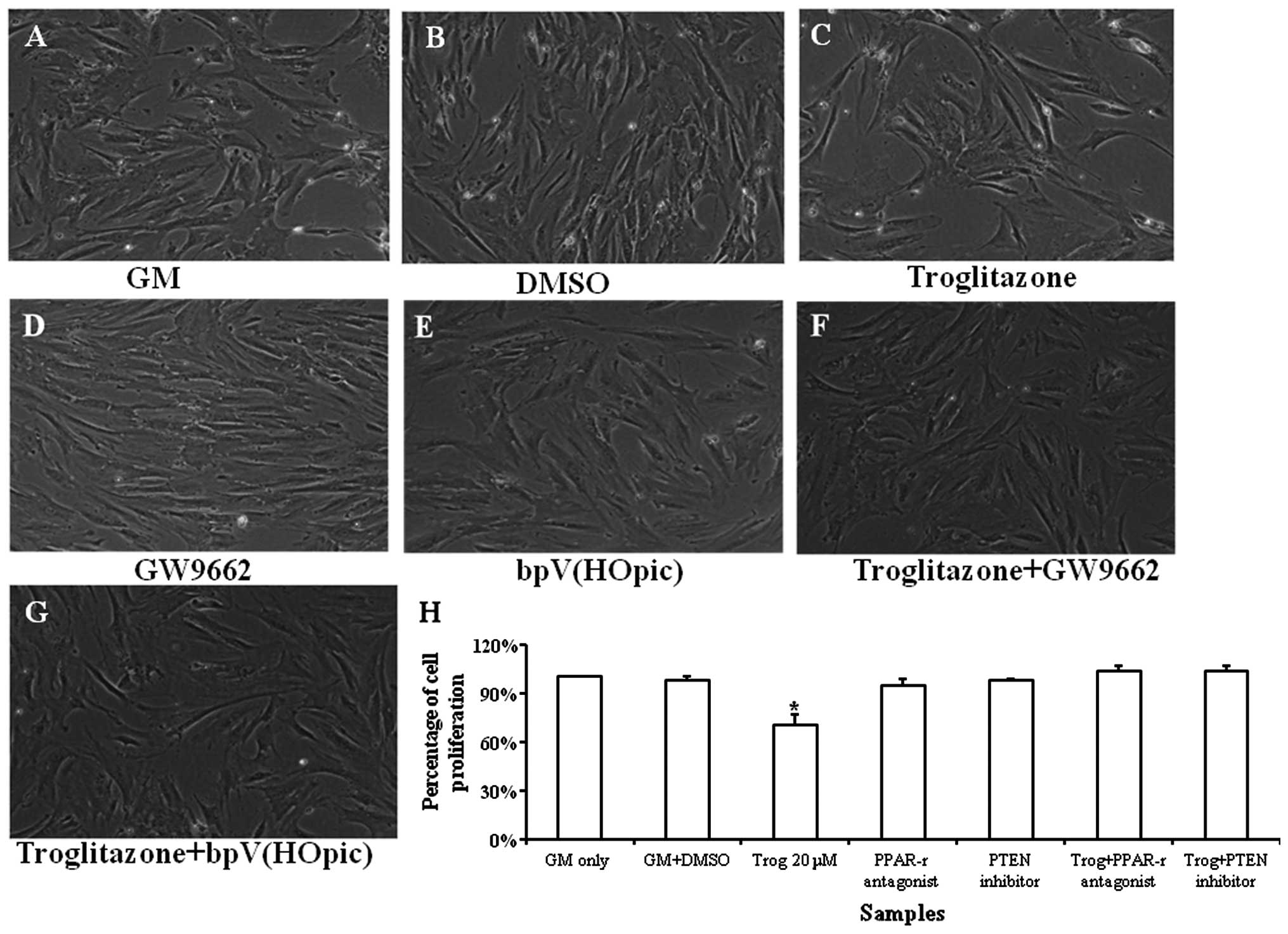

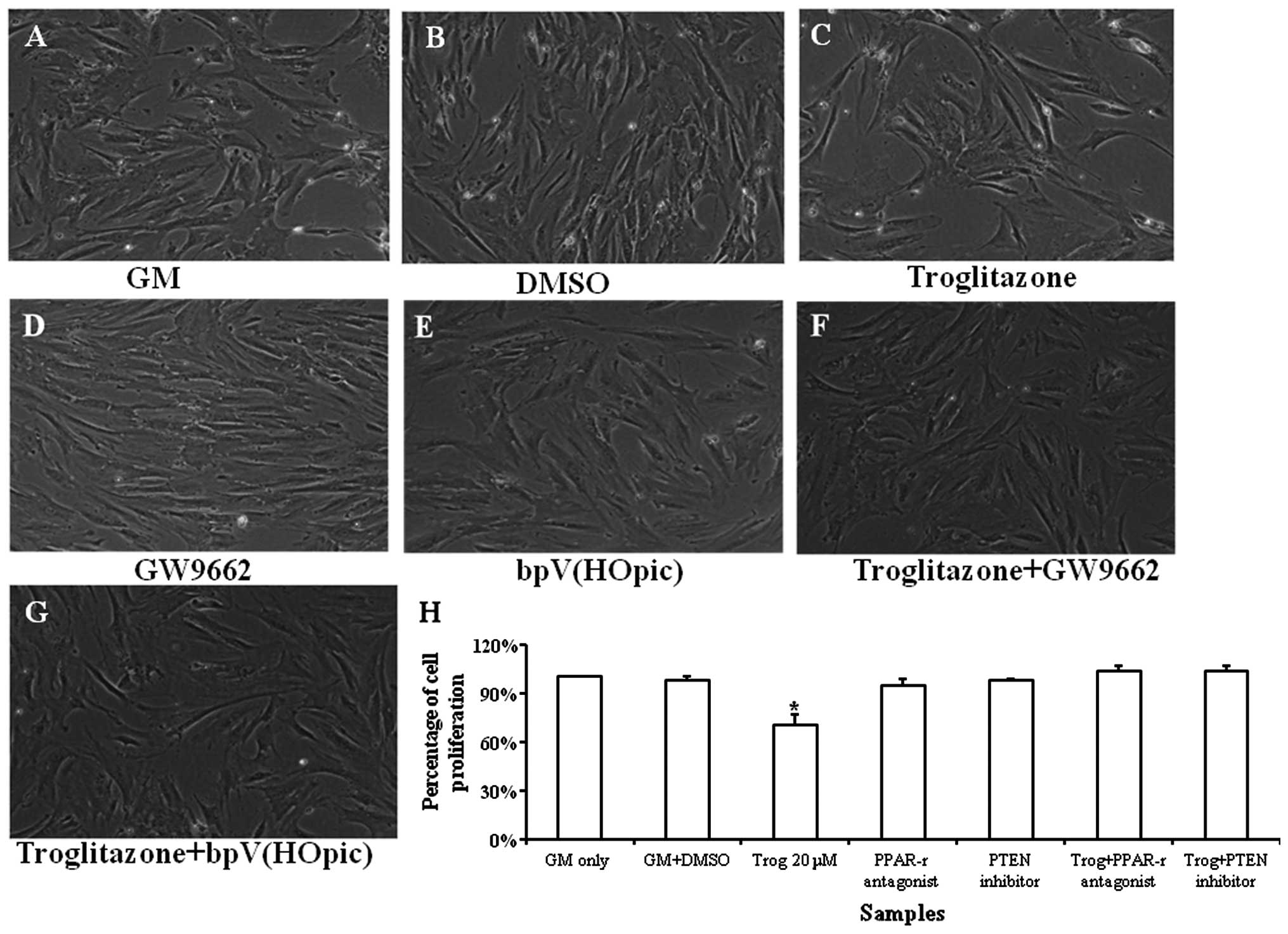

Typical images of the PASMC growth profile are shown

in Fig. 5A–G. Troglitazone

significantly reduced the proliferation rate of the PASMCs under

hypoxic conditions. bpV(HOpic) was used to determine whether the

PTEN inhibitor reversed the inhibitory effects of troglitazone on

PASMC proliferation. It was found that troglitazone did not reduce

the proliferation rate of the PASMCs that were pre-treated with

bpV(HOpic). These results suggest that troglitazone inhibits PASMC

proliferation by upregulating PTEN expression, which may be

reversed by the PTEN inhibitor (Fig.

5H).

| Figure 5Growth profile of pulmonary artery

smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) cultured in growth medium (GM)

supplemented with troglitazone, GW9662 and bpV(HOpic) for 72 h

under hypoxic conditions. Phase contrast images of (A) PASMCs

cultured in GM only, (B) GM supplemented with DMSO, (C) GM

supplemented with troglitazone, (D) GW9662, (E) bpV(HOpic), (F)

troglitazone + GW9662, (G) troglitazone + bpV(HOpic). (H)

Quantification of PASMCs treated with troglitazone, GW9662 and

bpV(HOpic). The cell number of PASMCs cultured in GM was regarded

as 100%. *P<0.05 vs. any other samples.

Magnification, ×100; Trog, troglitazone. The experiment was

performed in triplicate. |

GW9662 was also used to determine whether the

upregulation in PTEN expression stimulated by troglitazone was

mediated by the PPARγ signaling pathway. It was found that GW9662

reversed the inhibitory effects of troglitazone on PASMC

proliferation. These results suggest that troglitazone upregulates

PTEN expression through the PPARγ signaling pathway (Fig. 5).

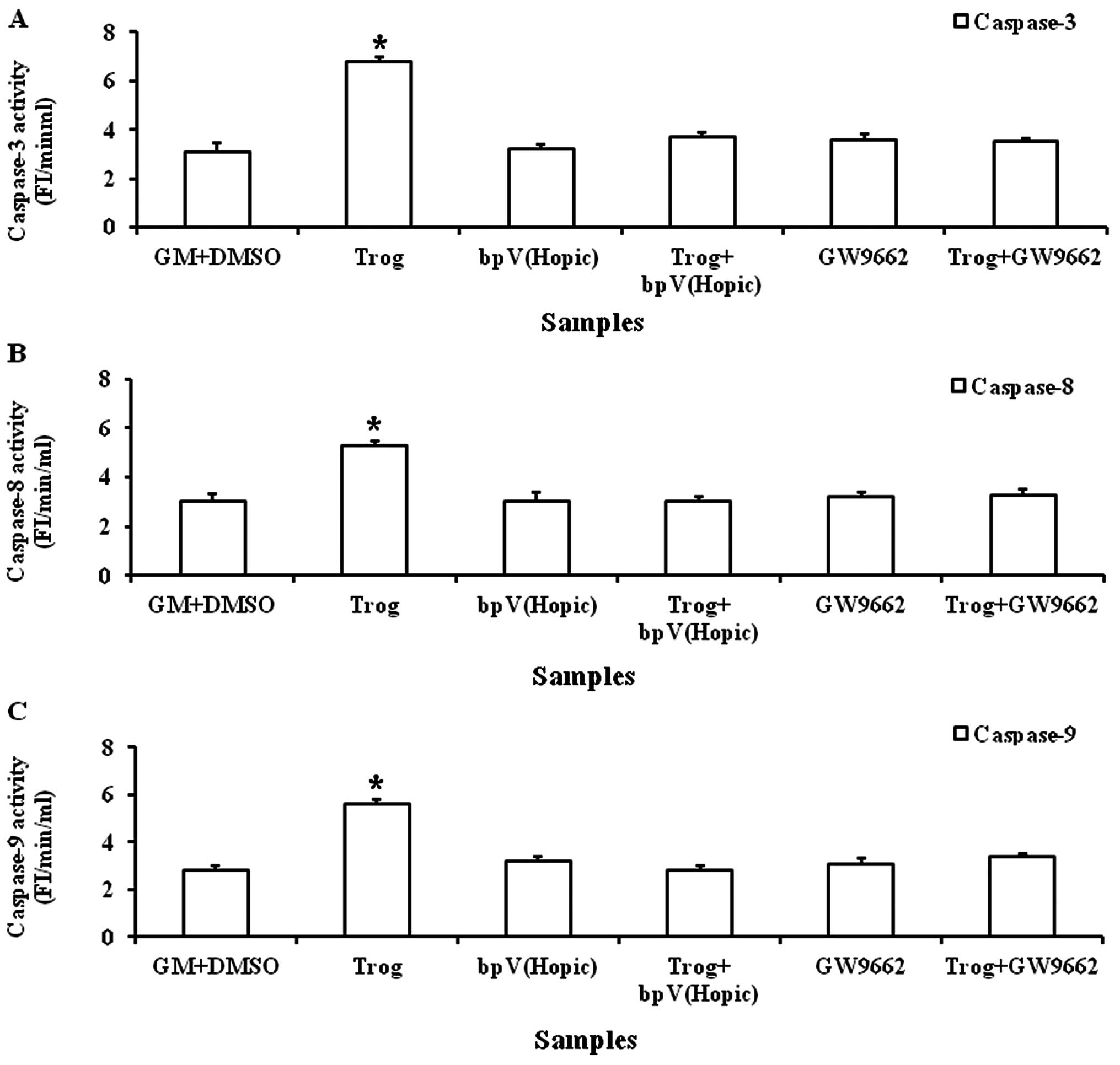

Troglitazone increases caspase-3, -8 and

-9 activities

A significantly increased caspase-3 activity was

observed when the PASMCs were cultured in GM (6.5±0.15 FI/min/ml)

supplemented with troglitazone for 8 h (Fig. 6A). Similarly, a significant

increase in caspase-8 and -9 activities was observed when the

PASMCs were cultured in GM (5.3±0.15 and 6.1±0.27 FI/min/ml)

supplemented with troglitazone for 8 h (Fig. 6B and C).

Troglitazone increases the apoptosis of

PASMCs under hypoxic conditions

TUNEL staining revealed that the apoptosis of PASMCs

cultured in BM increased after 72 h under hypoxic conditions

(Fig. 6D and E). Quantification

of TUNEL+ cells suggested that troglitazone

significantly increased the apoptotic PASMC number compared with

the cells cultured in BM alone (P<0.05).

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that troglitazone, a

high-affinity synthetic ligand of PPARγ upregulates PTEN gene and

protein expression levels in PASMCs under hypoxic conditions in a

concentration-dependent manner. In addition, we demonstrate that

troglitazone increases the apoptosis of PASMCs under hypoxic

conditions.

Pulmonary vascular remodelling in pulmonary arterial

hypertension is characterized by changes in pulmonary vascular

structure (1,2). This is partially caused by an

imbalance in PASMC proliferation and apoptosis (10). The increased proliferation and

decreased apoptosis of PASMCs result in the thickening of the

pulmonary vasculature, which subsequently increases pulmonary

vascular resistance and pulmonary arterial pressure (11).

Our results demonstrated that troglitazone at the

concentration of 20–80 μM effectively inhibited PASMC proliferation

under hypoxic conditions. The anti-proliferative effects of

troglitazone may be related to its role in the upregulation of PTEN

and the induction of the apoptosis of PASMCs under hypoxic

conditions. PPARγ expression has been found in pulmonary vascular

endothelial cells and SMCs (12,13). However its expression is reduced

in lung vascular cells of rats with pulmonary hypertension and in

patients with advanced primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension

(12). The targeted depletion of

PPARγ from SMCs has been shown to result in spontaneous pulmonary

hypertension in mice (4).

However, the activation of PPARγ with thiazolidinediones attenuates

vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension caused by

monocrotaline (14) or hypobaric

hypoxia (15) in rats.

Thiazolidinediones also reduce pulmonary hypertension in

ApoE-deficient mice fed high-fat diets (16) and attenuate hypoxia-induced

pulmonary hypertension and Nox4 expression and activity in mice

(5).

However, the role of PPARγ in the regulation of PTEN

expression of PASMCs under hypoxic conditions has not been examined

yet. Our results demonstrate that PPARγ upregulates PTEN gene and

protein expression levels. Studies have shown that PPARγ agonists

upregulate the transcription of PTEN in cancer cells. PPARγ

agonists have been used as tumor suppressors in breast cancer by

upregulating PTEN gene expression (17), while cells lacking PTEN or PPARγ

are unable to induce PTEN-mediated cellular events in the presence

of lovastatin or rosiglitazone. Zhang et al (7) showed that PTEN is required for the

rosiglitazone-induced inhibition of BEL-7404 cells. Rosiglitazone

upregulated PTEN expression in a concentration- and time-dependent

manner, which was mediated by PPARγ. Furthermore, PTEN

overexpression resulted in the inhibition of BEL-7404 cell

migration, and PTEN knockdown blocked the effects of rosiglitazone

on cell migration.

It is known that PPARγ agonists can stimulate the

production and secretion of ApoE, which has anti-proliferative

effects on human PASMCs (4).

Nisbet et al (5) found

that rosiglitazone attenuated hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular

remodelling and hypertension by suppressing oxidative and

proliferative signals. They found that rosiglitazone attenuated the

reduction in PTEN expression. However, the present study

demonstrates that troglitazone upregulates PTEN gene and protein

expression levels in human PASMCs under hypoxic conditions. This

may provide new insight into the mechanisms behind the

anti-proliferative effects of PPARγ on PASMCs under hypoxic

conditions.

The data from the present study also suggest that

troglitazone increases the apoptosis of PASMCs under hypoxic

conditions. It is known that chronic hypoxia can prolong the growth

of human vascular SMCs by inducing telomerase activity and telomere

stabilization (18). The

upregulation of PTEN negatively regulates the AKT/PKB signaling

pathway and leads to a decrease in p-AKT levels and, consequently,

to a decrease in AKT-mediated proliferation (19). Thus, a reduced p-AKT expression in

PASMCs was found after the addition of troglitazone in this study.

By reducing the cellular levels of p-AKT, PTEN downregulates cell

division and increases apoptosis. This may result in increased

activities of caspase-3, -8 and -9, thus inducing the apoptosis of

PASMCs under hypoxic conditions.

In conclusion, the present study highlights that

troglitazone increases PTEN gene expression at the transcriptional

level under hypoxic conditions in a concentration-dependent manner.

Troglitazone increases the apoptosis of PASMCs under hypoxic

conditions. The increased PTEN expression and apoptosis of PASMCs

provide new insight into the mechanisms behind the

anti-proliferative effects of troglitazone on PASMCs.

References

|

1

|

McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et

al: ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary

hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology

Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the

American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the

American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society,

Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation.

119:2250–2294. 2009.

|

|

2

|

Pietra GG, Edwards WD, Kay JM, et al:

Histopathology of primary pulmonary hypertension. A qualitative and

quantitative study of pulmonary blood vessels from 58 patients in

the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Primary Pulmonary

Hypertension Registry. Circulation. 80:1198–1206. 1989. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Nakaoka T, Gonda K, Ogita T, et al:

Inhibition of rat vascular smooth muscle proliferation in vitro and

in vivo by bone morphogenetic protein-2. J Clin Invest.

100:2824–2832. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Hansmann G, de Jesus Perez VA, Alastalo

TP, et al: An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPARgamma/apoE axis in human

and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin

Invest. 118:1846–1857. 2008. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Nisbet RE, Bland JM, Kleinhenz DJ, et al:

Rosiglitazone attenuates chronic hypoxia-induced pulmonary

hypertension in a mouse model. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.

42:482–490. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Lee KS, Park SJ, Hwang PH, Yi HK, Song CH,

Chai OH, Kim JS, Lee MK and Lee YC: PPAR-gamma modulates allergic

inflammation through up-regulation of PTEN. FASEB J. 19:1033–1035.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Zhang W, Wu N, Li ZX, Wang LY, Jin JW and

Zha XL: PPARgamma activator rosiglitazone inhibits cell migration

via upregulation of PTEN in human hepatocarcinoma cell line

BEL-7404. Cancer Biol Ther. 5:1008–1014. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ye L, Haider KhH, Esa WB, et al:

Liposome-based vascular endothelial growth factor-165 transfection

with skeletal myoblast for treatment of ischaemic limb disease. J

Cell Mol Med. 14:323–336. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Ye L, Lee KO, Su LP, et al: Skeletal

myoblast transplantation for attenuation of hyperglycaemia,

hyperinsulinaemia and glucose intolerance in a mouse model of type

2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 52:1925–1934. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhang S, Fantozzi I, Tigno DD, et al: Bone

morphogenetic proteins induce apoptosis in human pulmonary vascular

smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol.

285:L740–L754. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Barst RJ, McGoon M, Torbicki A, Sitbon O,

Krowka MJ, Olschewski H and Gaine S: Diagnosis and differential

assessment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol.

43:40S–47S. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Ameshima S, Golpon H, Cool CD, et al:

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma)

expression is decreased in pulmonary hypertension and affects

endothelial cell growth. Circ Res. 92:1162–1169. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Michalik L, Auwerx J, Berger JP, et al:

International Union of Pharmacology. LXI Peroxisome

proliferator-activated receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 58:726–741. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Matsuda Y, Hoshikawa Y, Ameshima S, et al:

Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands

on monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension in rats. Nihon

Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 43:283–288. 2005.(In Japanese).

|

|

15

|

Crossno JT Jr, Garat CV, Reusch JE, et al:

Rosiglitazone attenuates hypoxia-induced pulmonary arterial

remodeling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 292:L885–L897.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hansmann G, Wagner RA, Schellong S, et al:

Pulmonary arterial hypertension is linked to insulin resistance and

reversed by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma

activation. Circulation. 115:1275–1284. 2007.

|

|

17

|

Teresi RE, Shaiu C, Chen C, Chatterjee K,

Waite KA and Eng C: Increased PTEN expression due to

transcriptional activation of PPARgamma by Lovastatin and

Rosiglitazone. Int J Cancer. 118:2390–2398. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Minamino T, Mitsialis SA and Kourembanas

S: Hypoxia extends the life span of vascular smooth muscle cells

through telomerase activation. Mol Cell Biol. 21:3336–3342. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Maehama T and Dixon JE: The tumor

suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second

messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem.

273:13375–13378. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|