Introduction

Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) are mesenchymal

cells specialized in extracellular matrix synthesis, including

collagen, elastin and hyaluronic acid, in the dermis (1,2).

Dermal fibroblast proliferation is important in wound healing and

skin structure homeostasis (3).

Therefore, a growth factor was used for proliferating HDFs in

cosmetics (4).

Epidermal growth factor (EGF), one of various growth

factors, is a small polypeptide first purified by Cohen from the

submaxillary gland of adult male mice (5). EGF is important in cell

proliferation, migration and differentiation (5). These roles are mediated via

activation of the EGF receptor (EGFR), a transmembrane glycoprotein

with tyrosine kinase activity (6). Activated EGFR regulates

proliferation and migration via activation of intrinsic signaling

molecules (7,8). EGF is added to serum-free media in

in vitro cell culture systems as EGF is essential to cell

growth (9). Furthermore, EGF

exerts cytoprotective effects from cell damage, such as senescence

(10). Therefore, EGF is used as

an inducer of dermal fibroblast proliferation in cosmetics and

medicine (4).

Phytosphingosine-1-phosphate (PhS1P) is derived from

fungi and plants, and is structurally similar to

sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), an endogenous signal lipid in

mammalian cells (11,12). PhS1P is an agonist for S1P

receptors, with a particularly high affinity for S1P4

(13). S1P receptors include the

isomers, S1P1, S1P2, S1P3 and

S1P4, in mammalian cells (13). Since each receptor activates

different downstream signals, the effects of these S1Ps are

slightly different (14,15). Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the

PhS1P function in HDFs. The results showed that PhS1P altered gene

expression and induced EGF-dependent proliferation as a synergistic

effector.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and materials

HDFs were purchased from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland)

and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Gibco,

Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal

bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The cells were

incubated at 37°C in a humidified incubator containing 5%

CO2. PhS1P was obtained from Phytos Co., Ltd. (Suwon,

Korea).

RNA extraction and microarray

Total RNA was isolated using RiboEX (GeneAll, Seoul,

Korea) and quantified based on the optical density ratio (280/260

nm) using a Bioanalyzer 2100 (28S RNA/18S RNA ratio; Agilent

Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Equal amounts of RNA were used

to synthesize cDNA and label it with biotin using an RNA

amplification kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). After labeling, the

microarray was hybridized with biotin-labeled RNA and

streptavidin-Cy3 (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Following hybridization, the microarray was washed using wash E1BC

buffer and scanned using the iScan system (both from Illumina,

Hayward, CA, USA).

Microarray analyses

Microarray data were analyzed using Genespring GX

software version 11 (Agilent Technologies). mRNAs flagged ‘present’

in at least one sample were analyzed using fold-change. The

threshold cut-off was 1.3-fold for fold-change between non-treated

HDFs and PhS1P-treated HDFs. Significantly altered mRNAs were

sorted using the gene ontology (GO) tool.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(qPCR)

cDNA was synthesized using MMLV-reverse

transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. Synthesized cDNA was used for qPCR

(Line gene K; Bioer Technology, Co., Ltd., China) using specific

primers for cyclin A1, B1 and B2. Primers were designed by primer 3

(http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) (Table I). Expression was normalized to

β-actin.

| Table IQuantitative PCR primer sequences. |

Table I

Quantitative PCR primer sequences.

| Gene | Primer sequences |

|---|

| Cyclin A2 | Forward

5′-TTATTGCTGGAGCTGCCTTT-3′ |

| Reverse

5′-CTCTGGTGGGTTGAGGAGAG-3′ |

| Cyclin B1 | Forward

5′-CGGGAAGTCACTGGAAACAT-3′ |

| Reverse

5′-AAACATGGCAGTGACACCAA-3′ |

| Cyclin B2 | Forward

5′-TTGCAGTCCATAAACCCACA-3′ |

| Reverse

5′-GAAGCCAAGAGCAGAGCAGT-3′ |

MTT assay

Cell viability was assessed using

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT)

assay. HDFs were cultured for 24 h in 96-well plates with PhS1P and

EGF. MTT tetrazolium salt (0.5 mg/ml; Sigma) was added to cells for

4 h. After incubation, the medium was replaced with dimethyl

sulfoxide in each well. The absorbance of each sample was measured

at 595 nm using a plate reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA,

USA).

Results

PhS1P cytotoxicity in HDFs

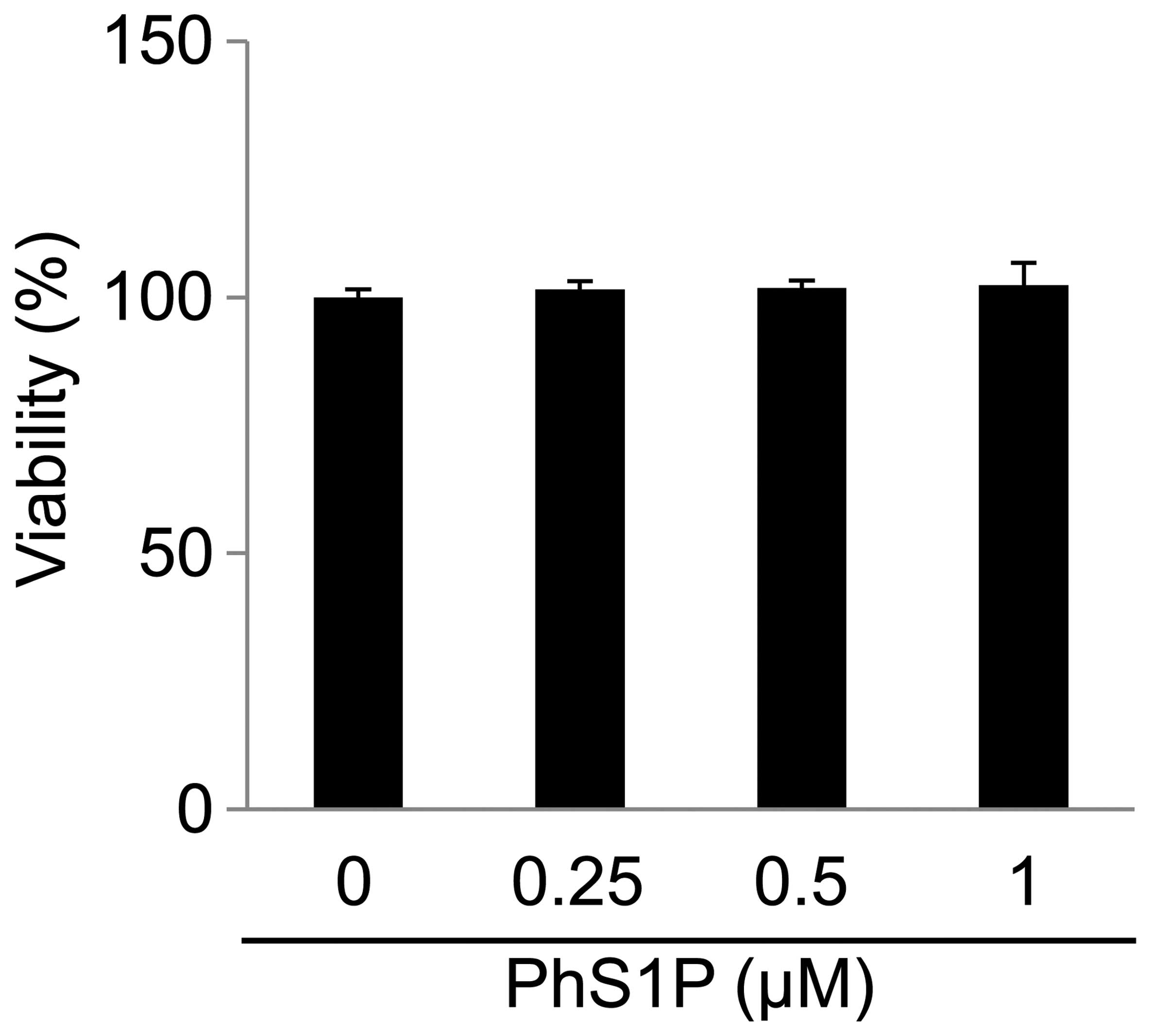

To assess the effect of PhS1P on cell viability,

HDFs were treated with various concentrations of PhS1P (0, 0.25,

0.5 and 1 μM) for 24 h (Fig. 1).

We determined that PhS1P at concentrations of ≤1 μM had no

cytotoxicity.

PhS1P alters the mRNA expression

profile

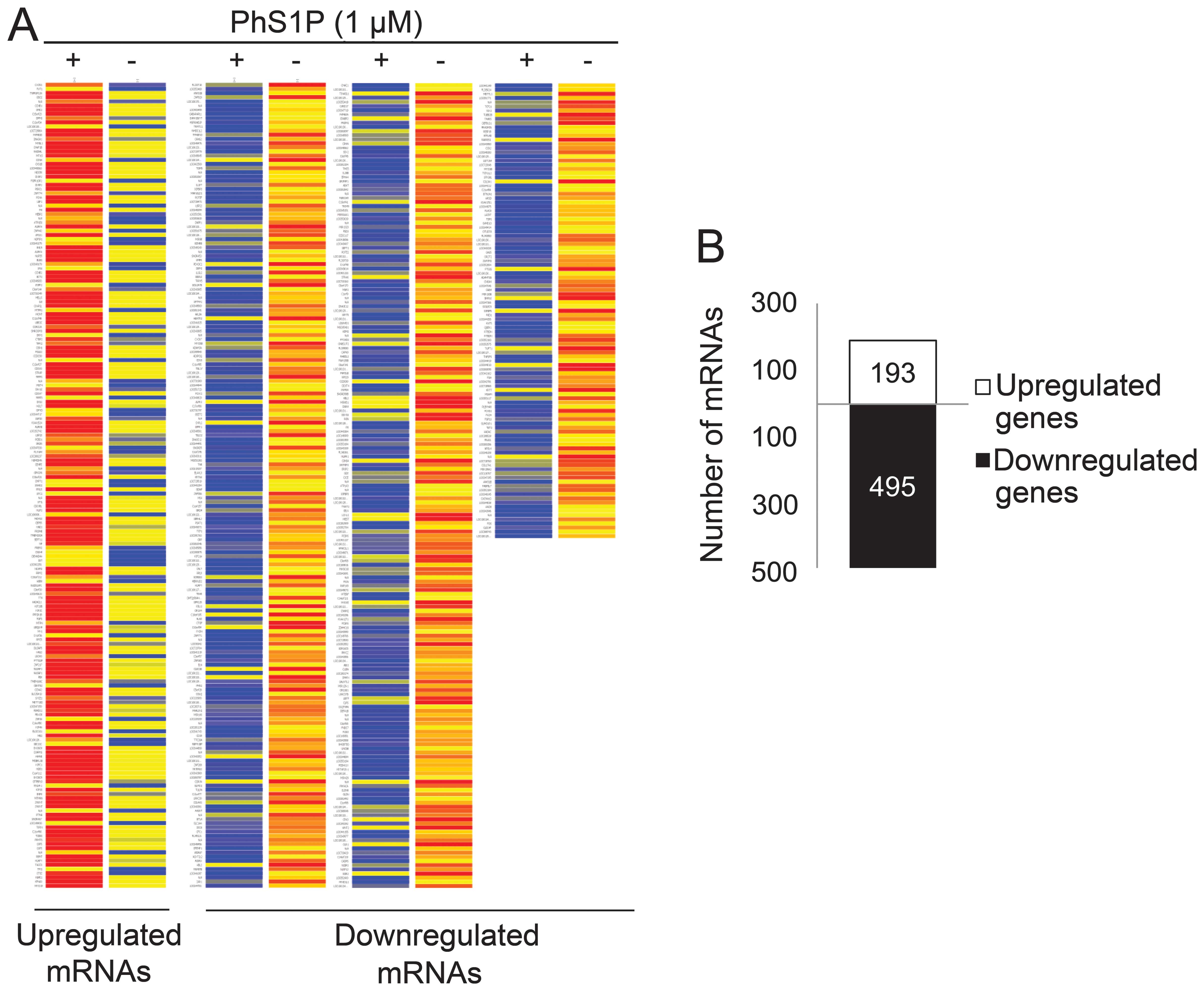

To identify genes that may play a PhS1P-dependent

role, we compared the expression profiles of non-treated and 1 μM

PhS1P-treated HDFs using the Illumina bead chip HumanHT-12. In

47,207 whole genes, we first filtered 35,973 genes that were

flagged ‘present’ with a frequency higher than the sensitivity of

detection in a minimum of one array. Fold-change was then analyzed

in these flag-filtered genes. Genes that changed by 1.3-fold

between non-treated and PhS1P-treated HDFs were presented on the

heat map (Fig. 2A). The analyses

identified 193 upregulated genes and 495 downregulated genes

(Fig. 2B).

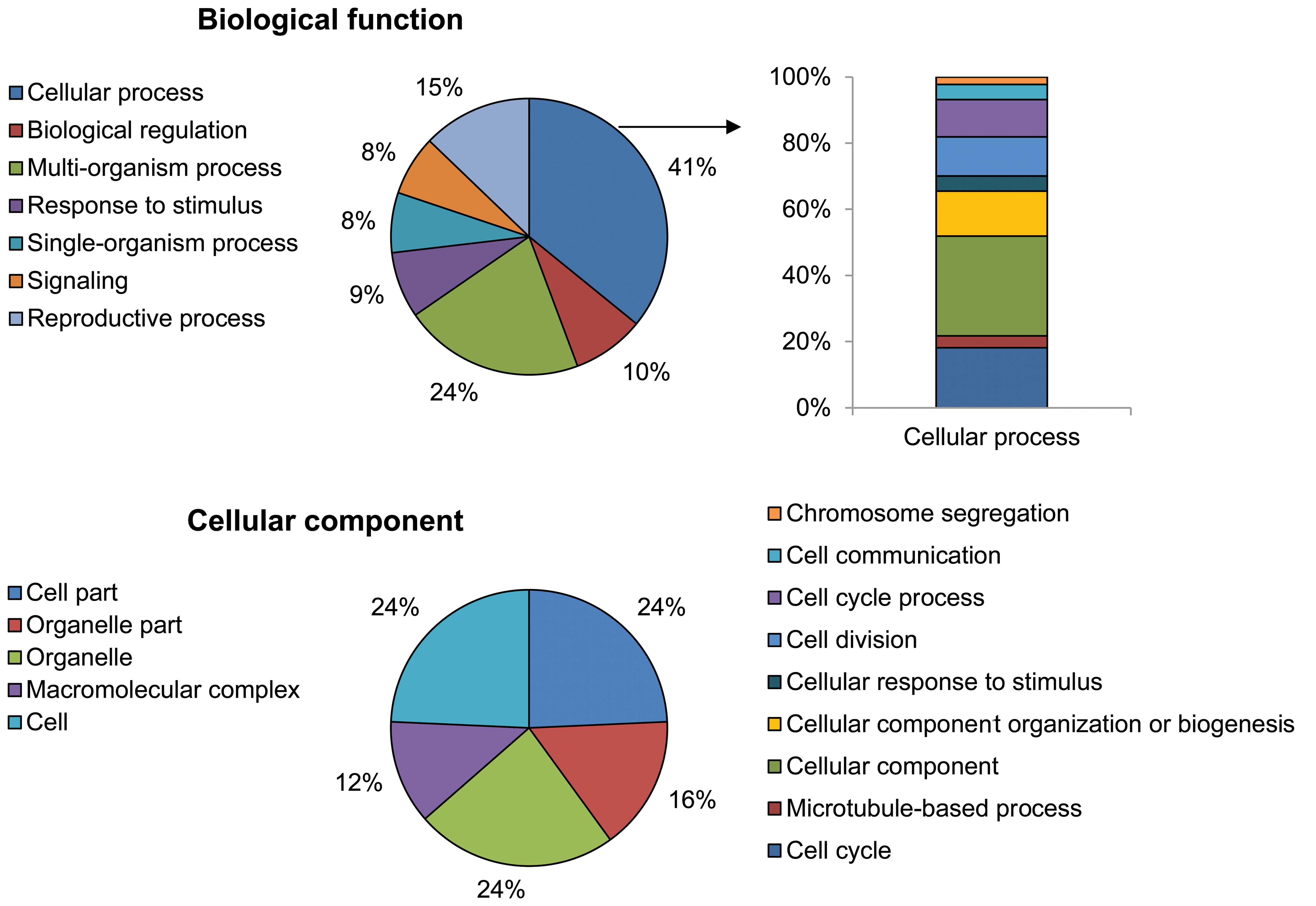

Using the GO analytical tool, the genes were sorted

based on their roles in biological processes (Fig. 3). Genes upregulated in

PhS1P-treated HDFs appeared to be involved in cell processes such

as cell cycle, cell division, microtubule-based processes,

chromosome segregation, cell communication, cellular responses to

stimuli, and cellular component organization or biogenesis. In

particular, cell cycle-related ontology (cell cycle, cell division

and chromosome segregation) was significantly enriched by

PhS1P.

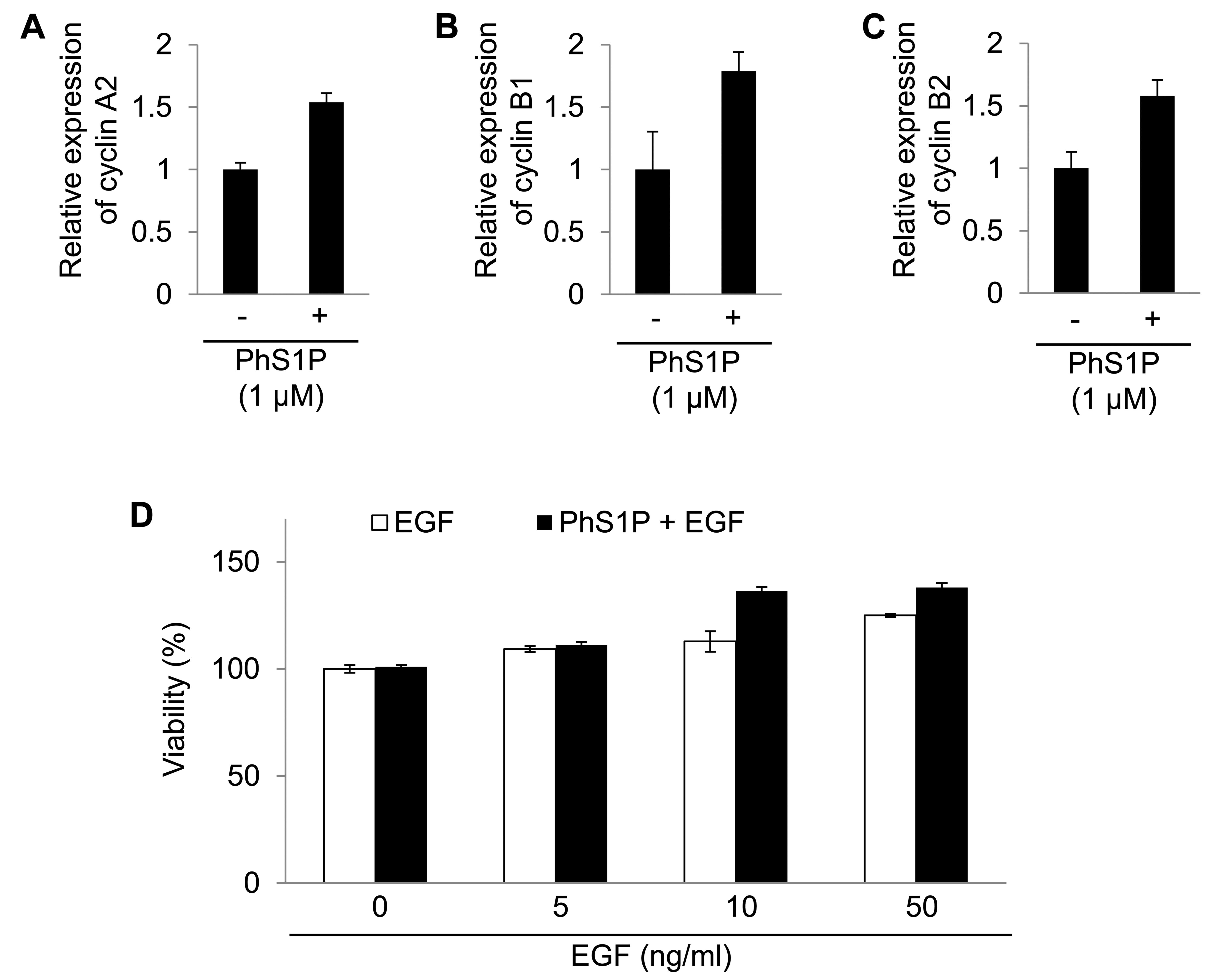

Cyclins A2, B1 and B2 were regulated by PhS1P.

Cyclins are well-known regulators in cells (16). Therefore, the analyses revealed

that PhS1P affected cell proliferation by altering specific mRNAs.

In addition, we confirmed the mRNA expression change of cyclin A2,

B1 and B2 using qPCR (Fig.

4).

We also examined the synergistic effect of PhS1P and

EGF on HDF viability. Compared with PhS1P-treated HDFs in the

absence of EGF, the viability of PhS1P-treated HDFs with EGF was

markedly increased (Fig. 4D).

These data indicate that PhS1P is a co-effector in the induction of

EGF-dependent cell proliferation.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effect of

PhS1P on EGF-induced proliferation in HDFs. PhS1P is

phytochemically derived from fungi, plants, and even mammalian

cells (12). In a previous study,

it was shown that PhS1P protects against hydrogen

peroxide-dependent growth arrest (17). Recent data from Lee et al

(17) suggested that PhS1P had no

significant effect on the proliferation at concentrations <1 μM

in HDFs (Fig. 1). However, PhS1P

(1 μM) regulates various cell cycle-related genes in HDFs (Fig. 2). In particular, the cyclins

(cyclin A2, B1 and B2), master regulators of the cell cycle, were

upregulated by PhS1P. Cyclin A2 regulates S-phase progression and

entry into mitosis (18,19). During S phase, cyclin A2 initiates

DNA synthesis (20). During the

G/M phase, cyclin A2 triggers entry into mitosis by activating

cyclin B1-Cdk1 (21).

In the progressing cell cycle, a sustained high

expression of cyclins is essential (16). However, overexpression of cyclins

is insufficient to induce cell cycle progression (22,23). As shown in Fig. 2, PhS1P upregulated mRNA expression

of cyclin A2, B1 and B2 although there was no change in cell

viability (Figs. 1 and 2).

Combining the present data with our previous data

(17), we determined that <1

μM PhS1P increases cyclin expression, but does not affect

viability. Moreover, EGF triggered proliferation in PhS1P-treated

HDFs (Fig. 4D). Therefore,

together with the results from Ikezawa et al (22), our data suggest that a

cyclin-enriched condition results in synergistic growth following

treatment with growth factors, such as EGF (24).

In summary, results of the present study have shown

that PhS1P regulates cell cycle-related genes. In addition, the

changes in gene expression synergistically trigger EGF-induced

proliferation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all other members of Damy

Chemical Co., Ltd. for their support. This study was supported by

the Konkuk University in 2012.

References

|

1

|

Crigler L, Kazhanie A, Yoon TJ, Zakhari J,

Anders J, Taylor B and Virador VM: Isolation of a mesenchymal cell

population from murine dermis that contains progenitors of multiple

cell lineages. FASEB J. 21:2050–2063. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Giro MG, Oikarinen AI, Oikarinen H, Sephel

G, Uitto J and Davidson JM: Demonstration of elastin gene

expression in human skin fibroblast cultures and reduced

tropoelastin production by cells from a patient with atrophoderma.

J Clin Invest. 75:672–628. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Schreier T, Degen E and Baschong W:

Fibroblast migration and proliferation during in vitro wound

healing. A quantitative comparison between various growth factors

and a low molecular weight blood dialysate used in the clinic to

normalize impaired wound healing. Res Exp Med (Berl). 193:195–205.

1993.

|

|

4

|

Allen G: Cosmetics - chemical technology

or biotechnology? Int J Cosmet Sci. 6:61–69. 1984. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Carpenter G and Cohen S: Epidermal growth

factor. J Biol Chem. 265:7709–7712. 1990.

|

|

6

|

Cohen S: The receptor for epidermal growth

factor functions as a tyrosyl-specific kinase. Prog Nucleic Acid

Res Mol Biol. 29:245–247. 1983. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dittmar T, Husemann A, Schewe Y, Nofer JR,

Niggemann B, Zänker KS and Brandt BH: Induction of cancer cell

migration by epidermal growth factor is initiated by specific

phosphorylation of tyrosine 1248 of c-erbB-2 receptor via EGFR.

FASEB J. 16:1823–1825. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Andl CD, Mizushima T, Nakagawa H, Oyama K,

Harada H, Chruma K, Herlyn M and Rustgi AK: Epidermal growth factor

receptor mediates increased cell proliferation, migration, and

aggregation in esophageal keratinocytes in vitro and in vivo. J

Biol Chem. 278:1824–1830. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Halleux C and Schneider YJ: Iron

absorption by CaCo2 cells cultivated in serum-free

medium as in vitro model of the human intestinal epithelial

barrier. J Cell Physiol. 158:17–28. 1994.

|

|

10

|

Shiraha H, Gupta K, Drabik K and Wells A:

Aging fibroblasts present reduced epidermal growth factor (EGF)

responsiveness due to preferential loss of EGF receptors. J Biol

Chem. 275:19343–19351. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Kim MK, Park KS, Lee H, Kim YD, Yun J and

Bae YS: Phytosphingosine-1-phosphate stimulates chemotactic

migration of L2071 mouse fibroblasts via pertussis toxin-sensitive

G-proteins. Exp Mol Med. 39:185–194. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Pata MO, Hannun YA and Ng CK: Plant

sphingolipids: decoding the enigma of the Sphinx. New Phytol.

185:611–630. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Inagaki Y, Pham TT, Fujiwara Y, Kohno T,

Osborne DA, Igarashi Y, Tigyi G and Parrill AL: Sphingosine

1-phosphate analogue recognition and selectivity at S1P4 within the

endothelial differentiation gene family of receptors. Biochem J.

389:187–195. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Takuwa N, Du W, Kaneko E, Okamoto Y,

Yoshioka K and Takuwa Y: Tumor-suppressive sphingosine-1-phosphate

receptor-2 counteracting tumor-promoting sphingosine-1-phosphate

receptor-1 and sphingosine kinase 1 - Jekyll Hidden behind Hyde. Am

J Cancer Res. 1:460–481. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Takuwa Y, Du W, Qi X, Okamoto Y, Takuwa N

and Yoshioka K: Roles of sphingosine-1-phosphate signaling in

angiogenesis. World J Biol Chem. 1:298–306. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Malumbres M and Barbacid M: Cell cycle,

CDKs and cancer: a changing paradigm. Nat Rev Cancer. 9:153–166.

2009. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lee JP, Cha HJ, Lee KS, Lee KK, Son JH,

Kim KN, Lee DK and An S: Phytosphingosine-1-phosphate represses the

hydrogen peroxide-induced activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in

human dermal fibroblasts through the phosphatidylinositol

3-kinase/Akt pathway. Arch Dermatol Res. 304:673–678. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ohashi A, Imai H and Minami N: Cyclin A2

is phosphorylated during the G2/M transition in mouse two-cell

embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 66:343–348. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Alexandrow MG and Hamlin JL: Cdc6

chromatin affinity is unaffected by serine-54 phosphorylation,

S-phase progression, and overexpression of cyclin A. Mol Cell Biol.

24:1614–1627. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Yam CH, Fung TK and Poon RY: Cyclin A in

cell cycle control and cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 59:1317–1326.

2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Fung TK, Ma HT and Poon RY: Specialized

roles of the two mitotic cyclins in somatic cells: cyclin A as an

activator of M phase-promoting factor. Mol Biol Cell. 18:1861–1873.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ikezawa K, Ohtsubo M, Norwood TH and

Narayanan AS: Role of cyclin E and cyclin E-dependent kinase in

mitogenic stimulation by cementum-derived growth factor in human

fibroblasts. FASEB J. 12:1233–1239. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chou JL, Fan Z, DeBlasio T, Koff A, Rosen

N and Mendelsohn J: Constitutive overexpression of cyclin D1 in

human breast epithelial cells does not prevent G1 arrest induced by

deprivation of epidermal growth factor. Breast Cancer Res Treat.

55:267–283. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Fisher D, Krasinska L, Coudreuse D and

Novák B: Phosphorylation network dynamics in the control of cell

cycle transitions. J Cell Sci. 125:4703–4711. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|