Osteoporosis is as a skeletal disorder characterized

by reduced bone mineralization and strength, leading to an

increased risk of fractures (1).

The overall prevalence of osteoporosis worldwide has been estimated

at 18.3%, with an almost 2-fold higher prevalence in females

(23.1%) than males (11.7%) (2).

Osteoporosis is also characterized by high geographic differences,

with the highest prevalence in Africa (26.9%) (3). Yet, even in developed countries,

the economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures is

significant, with annual costs of 17.9 billion USD and 4 billion

GBP in the USA and UK, respectively (4). The geographic heterogeneity of

osteoporosis is mediated by the distinct prevalence of risk

factors, including genetic patterns, environmental factors,

sedentary lifestyle, smoking, alcohol use, medications

(glucocorticoids), morbidities (hyperparathyroidism, rheumatoid

arthritis, diabetes mellitus, cancer), as well as nutritional

deficiencies (5).

The objective of the present review was to highlight

the molecular mechanisms of the effects of vitamin groups A, C, E,

K and B on bone and their potential role in the development of

osteoporosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

comprehensive review focusing on the association between the intake

of vitamins A, C, E and K, and group B vitamins and osteoporosis

since the article by Ahmadieh and Arabi (16) published over than a decade ago

and focusing mainly on epidemiological data. Since the publication

of the aforementioned study (16) significant progress has been made

in understanding the molecular mechanisms of vitamin functions in

bone has been achieved, while epidemiological studies provided

additional evidence on the association between vitamin status and

osteoporosis. Therefore, in the present review, the role of vitamin

forms and doses and their biological effects on bone tissue are

discussed in detail, with particular focus on the most recent

findings. Given the high prevalence of osteoporosis and vitamin

deficiency worldwide, the further understanding of the role of

vitamins as osteoprotective agents may markedly improve the

prevention of and treatment strategies for osteoporosis, as well as

prevent adverse effects of excessive supplementation.

Vitamin E (VE) is a fat-soluble vitamin with

antioxidant activity that is present in the form of tocopherols

(α-, β-, γ- and δ-) and tocotrienols (α-, β-, γ- and δ-) (17). VE is considered as

bone-protecting due to its complex effects on bone physiology that

are not limited to its antioxidant activity (18). A Mendelian randomization study

demonstrated a significant positive association between circulating

α-tocopherol levels and bone mineral density (BMD) (19). A low serum VE level has been

found to be associated with a reduced BMD, and has therefore been

considered a risk factor for osteoporosis in post-menopausal women

(20).

Correspondingly, low serum α-tocopherol

concentrations have been found to be associated with a 51 and 58%

increase in the hazard ratio of hip fractures in older Norwegians

(21) and Swedes (22). In turn, supplementation with

tocotrienol, a form of VE, for 12 weeks was shown to decrease

oxidative stress and bone resorption in post-menopausal women with

osteopenia (23,24).

Despite a positive association between serum

α-tocopherol and femoral neck BMD observed in the Aberdeen

Prospective Osteoporosis Screening Study, the authors considered

this association to lack biological significance (25). However, the analysis of NHANES

2005-2006 data demonstrated an inverse association between the

serum α-tocopherol levels and femoral neck BMD following adjustment

for confounders (26).

Notably, serum α-tocopherol, but not γ-tocopherol,

has been found to be inversely associated with bone formation

marker, procollagen type 1 amino-terminal propeptide, in

post-menopausal women (27).

These findings generally corroborate the earlier observed inverse

relationship between α-tocopherol intake and γ-tocopherol levels

(28).

In addition, tocotrienol supplementation has been

shown to improve bone calcination in testosterone

deficiency-associated osteoporosis (31). In ovariectomy-induced

osteoporotic fractures, α-tocopherol supplementation has been found

to significantly improve fracture healing, although it does not

increase callous bone volume in rats (32), nor does it improve bone strength

(33). It has been shown that

both an intraperitoneal (34)

and intramuscular (35)

injection with α-tocopherol significantly increases BMD and

osteogenesis, as well as osteoblast activity in a rabbit model of

distraction osteogenesis.

Correspondingly, VE deficiency has been shown to

alter exercise-induced plasma membrane disruptions, membrane repair

and the survival of osteocytes (36). The co-administration of Se and

vitamin C (VC) with VE significantly increases its efficiency in

the improvement of bone structure (37). In turn, excessive VE intake has

failed to induce bone loss in an animal model of

ovariectomy-induced osteoporosis (38), as well as in normal female rats

(39).

The association between VE intake and bone health

established in the aforementioned epidemiological studies is

mediated by the influence of tocopherols and tocotrienols on bone

physiology.

In agreement with the role of VE as an antioxidant,

tocopherol has been shown to promote the osteogenic differentiation

and oxidative stress resistance of rat bone marrow-derived

mesenchymal stem cells by inhibiting

H2O2-induced ferroptosis by increasing the

phosphorylation of PI3K, Akt and mammalian target of rapamycin

(mTOR) (40).

α-tocopherol-stimulated osteoblastogenesis has been shown to be

associated with the upregulation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP)2,

TGF1β, fibroblast growth factor receptor 1, MMP-2, muscle segment

homeobox 2, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-1, VEGF-B, Runx2,

Smad2 and other genes, whereas the expression of

osteopetrosis-associated transmembrane protein 1,

microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) and EGFR

genes is downregulated (41). VE

has been shown to reduce osteocyte apoptosis in a model of

steroid-induced osteonecrosis through inhibition of caspase-3

expression and upregulation of Bcl-2 (42). At the same time, α-tocopherol and

δ-tocopherol may also inhibit osteoblast differentiation from the

early stages of osteogenesis to the osteoid-producing stage

(43). At the same time, both

α-tocopherol (100 and 200 μM) and δ-tocopherol (2 and 20

μM) significantly reduces osteoblast differentiation

(43).

In addition to the promotion of osteoblast

differentiation, tocopherol has been shown to inhibit IL-1-induced

osteoclastogenesis through the downregulation of receptor activator

of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) mRNA expression (44). The VE-induced inhibition of

osteoclastogenesis may also be associated with reduced monocyte and

lymphocyte production (45). In

addition, treatment with 10-20 μM α-tocopherol has been

shown to result in reduced bone mass by upregulating osteoclast

fusion via p38 MAPK and MITF activation (46).

It has also been demonstrated that another form of

VE, tocotrienol, may also significantly modulate bone formation and

resorption (47) in a distinct

manner of that observed for tocopherols (48). γ-tocotrienol significantly

promotes Runx2-dependent osteoblastogenesis with the upregulation

of ALP, osteocalcin (OCN) and type I collagen (49). Annatto-derived tocotrienol has

been found to significantly increase osteoblast differentiation, as

evidenced by increased osterix (OSX), COL1α1, ALP and OCN gene

expression, and enhanced mineralization (50).

Tocotrienol also significantly increases

mineralization in osteoblasts by increasing BMP-2 protein

expression in association with the downregulation of RhoA

activation and HMG-CoA reductase gene expression (51). The tocotrienol-induced

upregulation of BMP-2 and BMP-4 gene expression has also been shown

to be associated with the stimulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling

(52). d-δ-tocotrienol (0-25

μmol/l) has been shown to induce MC3T3-E1 preosteoblast

differentiation through the upregulation of BMP-2 and the

inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase expression, resulting in

mineralized nodule formation (53).

δ-tocotrienol also promotes osteoblast migration

through an increase in Akt phosphorylation and Wnt/β-catenin

signaling activation (54).

Notably, at low doses, γ-tocotrienol has been shown to exert

protective effects on osteoblasts against

H2O2-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis,

whereas high doses are cytotoxic and induce apoptotic cell death

(55). It has also been

demonstrated that δ-tocotrienol protects osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 and

MLO-Y4 cells from oxidative stress and subsequent apoptosis through

the upregulation of glutathione production and the upregulation of

the PI3K/Akt and nuclear factor-erythroid factor 2-related factor 2

(Nrf2) signaling pathways (56).

The osteogenic effects of γ-tocotrienol on human bone

marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells have been shown to be

mediated by the promotion of p-AMPK and p-Smad1 phosphorylation

(57).

α-Tocotrienol, but not α-tocopherol, has been shown

to reduce osteoclastogenesis (58) through the inhibition of RANKL

expression along with the downregulation of c-Fos expression

(59). Specifically,

γ-tocotrienol has been shown to inhibit RANKL mRNA expression,

while increasing osteoprotegerin (OPG) mRNA expression in human

bone-derived cells, whereas α-tocopherol is capable of only

upregulating OPG expression (60). Tocotrienol has also been shown to

inhibit IL-17-induced osteoclastogenesis in rheumatoid arthritis

fibroblast-like synoviocytes through the downregulation of mTOR,

ERK and IκB phosphorylation, and the inhibition of RANKL mRNA

expression, while increasing AMPK phosphorylation (61). In a model of metabolic

syndrome-associated osteoporosis supplementation with tocotrienol,

there was a significant reduction in RANKL and FGF-23 expression,

as well as a reduction in Dickkopf-related protein (DKK)-1 levels,

being indicative of Wnt pathway activation (62) (Fig. 1).

Annatto bean-derived tocotrienol has also been shown

to prevent bone resorption in testosterone-deficiency-associated

osteoporosis in rats (63).

γ-tocotrienol also reduces ovariectomy-induced bone loss in mice

through HMG-CoA reductase inhibition (64). Moreover, palm oil-derived

tocotrienols have been shown to prevent bone loss in ovariectomized

rats more effectively than Ca2+ (65). The inhibition of skeletal

sclerostin expression may be also responsible for the

anti-osteoporotic effects of annatto tocotrienol in ovariectomized

rats in parallel with the reduction of the RANKL/OPG ratio

(66). According to the positive

role of tocotrienols in the prevention of bone resorption, these

were considered as the potential treatment strategy for

menopause-associated osteoporosis (67).

In general, VE may be considered as an

osteoprotective agent, although the biological effects are strongly

dependent on the specific forms. Epidemiological studies have

demonstrated that the serum α-tocopherol level is significantly

associated with BMD, whereas its deficiency is related to an

increased risk of fractures, although certain inconsistencies

exist. Both tocopherol and tocotrienol isomers significantly

increase bone quality and promote regeneration in animal models of

osteoporosis. α-tocopherol has been shown to exert osteogenic

effects due to its antioxidant effects, the inhibition of

osteoblast ferroptosis and apoptosis, as well as the activation of

the TGF1β/Smad and PI3K/Akt pathways. Even more potent osteogenic

effects have been demonstrated for tocotrienol that promote BMP-2

and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, also activating Akt and protecting the

cells from oxidative stress and apoptosis. The inhibitory effects

of both tocopherol and tocotrienol on osteoclast formation have

been shown to be mediated by the inhibition of

inflammation-associated RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis.

Therefore, dietary VE as tocotrienol, has been shown to exert

osteoprotective effects in laboratory studies, although

epidemiological data are available only for tocopherol.

VK has been shown to be a cost-effective strategy

for preventing fractures in older women (70). A recent meta-analysis of 16

randomized controlled trials with 6,425 subjects involved

demonstrated that VK2 supplementation significantly

improved BMD and reduced the risk of fractures (71), as well as undercarboxylated OCN

levels (72) in post-menopausal

women. Similarly, other meta-analyses have demonstrated positive

impact of vitamin K on BMD and fracture risk (73). Correspondingly, in 10-year

follow-up studies, a higher dietary intake of VK was shown to be

associated with a 24% decrease in the relative fracture risk

(74). Each 1 μg/l

increase in serum VK1 (phylloquinone) levels was associated with a

45% reduction in fracture risk in post-menopausal osteoporosis due

to an increase in hip strength (75). However, no significant effects of

phylloquinone intake on bone turnover or bone mass were observed in

adult patients with Crohn's disease (76). In turn, low plasma phylloquinone

levels were associated with a higher incidence of vertebral

fractures, although no significant difference in BMD in subjects

with low and high plasma K1 levels was observed (77). VK intake was also shown to be

inversely associated with undercarboxylated OCN that was negatively

associated with lumbar BMD and was directly interrelated with

urinary type-I collagen cross-linked-N-telopeptide levels, a marker

for bone resorption (78).

A previous meta-analysis demonstrated that the

combination of vitamin D with VK significantly increased total BMD

with the more profound effect observed in VK2 users

(79). The co-supplementation of

phylloquinone with vitamin D3 and calcium has been shown to

increase BMD and bone mineral content (BMC) at the ultradistal

radius (80). The combined

administration of VK and Ca2+ also possessed positive

effect on BMD, as evidenced by a recent meta-analysis (81). Correspondingly, a low dietary

Ca2+ and VK intake was considered a risk factor for

osteoporotic fractures in women (82). In a previous study, a 3-year

low-dose MK-7 supplementation in healthy post-menopausal women

significantly reduced the aging-associated decrease in lumbar spine

and femoral neck BMD and BMC, vertebral height and bone strength

(83). The administration of 375

μg MK-7 for 12 months prevented an increase in trabecular

spacing and the reduction of trabecular number in post-menopausal

women with osteopenia (84). The

results of a 24-month trial demonstrated a significant reduction in

the incidence of fractures in patients with osteoporosis

supplemented with MK-4 when compared to the control groups

(85). Consistently, the results

from a meta-analysis demonstrated that MK-4 intake significantly

improved BMD and decreased the risk for vertebral fractures as

compared to treatment with the placebo (86).

In animal models of osteoporosis, VK has also been

shown to exert osteoprotective effects. Specifically, VK

supplementation was even shown to be more effective in the

improvement of bone characteristics in a model of immobilization

osteoporosis as compared to combined Ca2+ and vitamin D

administration (91). A similar

protective effect of VK2 (menatetrenone) was observed in

a model of glucocorticoid- (92,93) and hyperglycemia-induced (94) bone loss. MK-7 has been shown to

promote diaphyseal and metaphyseal Ca2+ deposition due

to increased osteoblastic proliferation and differentiation

(95). Moreover, MK-7, but not

MK-4 intake, has also bees shown to improve bone microstructure

characterized by higher trabecular number, improved trabecular

architecture and greater bone volume in ovariectomized rats

(96).

The results obtained from laboratory studies are

generally consistent with those from the epidemiological studies,

also demonstrating the osteogenic effects of VK, although the

specific effects and underlying mechanisms have been shown to be

greatly dependent on the forms and homologues of VK.

MK-7 has been shown to promote MC3T3E1 cell

differentiation characterized by an increased OCN, OPG and RANKL

mRNA expression (97).

Menaquinone-7 treatment also increases osteoblast migration and

activity along with the downregulation of Runx2 expression,

indicative of promotion of cell maturation (98). MK-7-induced osteogenesis has also

been found to be associated with a significant increase in BMP-2

mRNA expression, tenascin C gene expression and increased p-Smad1

levels in MC3T3E1 cells (99).

MK-7 promotes vitamin D3-induced osteogenesis that may be at least

partially mediated by the enhanced expression of genes, including

growth differentiation factor-10 (GDF10), IGF1, VEGFA and

fms-related tyrosine kinase 1 (FLT1) (100). Concomitantly,

hydrophobins-modified menaquinone-7 has been shown to be more

effective in increasing osteoblast differentiation, while reducing

osteoclastogenesis in MC3T3-E1 cells, as compared to native MK-7

(101). It has also been

demonstrated that MK-7 inhibits basal and cytokine-induced NF-κB

signaling through an increase in IκB mRNA expression, and

ameliorates TNFα-induced inhibition of SMAD signaling (102). These findings generally

resemble the earlier observed amelioration of inhibitory effect of

inflammation on osteogenesis through down-regulation of

IL-6-induced JAK/STAT signaling upon VK2 treatment

(103).

MK-4 has been shown to be the most potent promotor

of bone formation compared to estrogen, icariin, lactoferrin and

lithium chloride (104). It has

been sown that menaquinone 4 inhibits ovariectomy-induced bone loss

by increasing osteoblast activity with the stimulation of BMP-2 and

Runx2 signaling, and the downregulation of osteoclast

differentiation (105).

Correspondingly, the osteogenic effect of MK-4 has been shown to be

mediated by the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

(106). In addition to

increased osteoblast proliferation, the osteogenic effect of MK-4

may be associated with the inhibition of Fas-induced osteoblast

apoptosis (107).

Correspondingly, MK-4 also prevents osteoblast apoptosis through

the upregulation of FoxO signaling and the reduction of reactive

oxygen species (ROS) production (108), in agreement with the observed

upregulation of SIRT1 signaling and the inhibition of mitochondrial

dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) (109). At the same time, MK-4 reduces

excessive bone mineralization induced by Mg deficiency (110). It is also notable that in

vascular smooth muscle cells, MK-4 reduces

β-glycerophosphate-induced calcification by downregulating BMP-2

and Smad1 expression (111).

Several studies have demonstrated that VK is capable

of inducing osteoblast formation, while inhibiting osteoclast

differentiation and bone-resorbing activity. Specifically, in a

culture of bone marrow cells, MK-4 was found to significantly

inhibit adipogenic and osteoclastogenic differentiation, while

promoting osteoblast differentiation (118). It has been demonstrated that,

in comparison to VK1 and VK3, MK7 and particularly MK4, are more

effective in the promotion of osteoblast activity and the

inhibition of osteoclastic bone resorption (119), although another study

demonstrated a higher anti-osteoclast activity for MK7 (120). Both phylloquinone (VK1) and

menaquinone-4 have been shown to promote osteogenesis, as evidenced

by increased OCN and OPG levels in parallel with decreased

circulating RANKL levels in a model of high-fat-induced obesity

(121). Both MK-4 and VK1

significantly reduce dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced osteoclastogenesis

mainly by reducing RANKL expression (observed at 1.0 μM),

whereas the upregulation of OPG expression has been observed at

higher exposure levels (10 μM) (122). MK-4 also reduced

1,25(OH)2D3-induced formation of multinucleated osteoclasts

(123). It has been also

demonstrated that MK-7 ameliorated parathyroid hormone (PTH) and

prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)-induced bone resorption by osteoclasts

(124,125).

The inhibition of RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis

by menaquinone 4 and 7 has been found to be dose-dependent

(126). The MK-4-induced

inhibition of RANKL signaling has been shown to result in the

subsequent reduction of nuclear factor of activated T-cells 1

(NFATc1), osteoclast-associated receptor and cathepsin K mRNA

expression (127). In addition

to the downregulation of RANKL signaling, menaquinone 4 or VK1 have

been shown to inhibit macrophage colony stimulating factor

(M-CSF)-induced osteoclast differentiation in a dose-dependent

manner (128).

Although OCN is an abundant protein of bone

extracellular matrix, its functioning has been shown to not be

responsible for the regulation of bone development; rather, it

plays a crucial role in the improvement of bone strength by

adjustment of biological apatite parallel to collagen fibrils

(131), as well as carbohydrate

metabolism regulation in its uncarboxylated form (132). At the same time, the VK-induced

decrease in the level of undercarboxylated OCN did not induce

insulin resistance, and the change in percentage of

undercarboxylated OCN is directly associated with the improvement

of glucose sensitivity (133).

Moreover, VK treatment has been shown to increase OCN gene

expression, resulting in an improvement of β-cell proliferation and

adiponectin production, thus exerting a hypoglycemic effect

(134). In agreement with this,

insulin signaling in osteoblasts has been shown to result in

reduced OCN γ-carboxylation, thus increasing its hypoglycemic

effect (135).

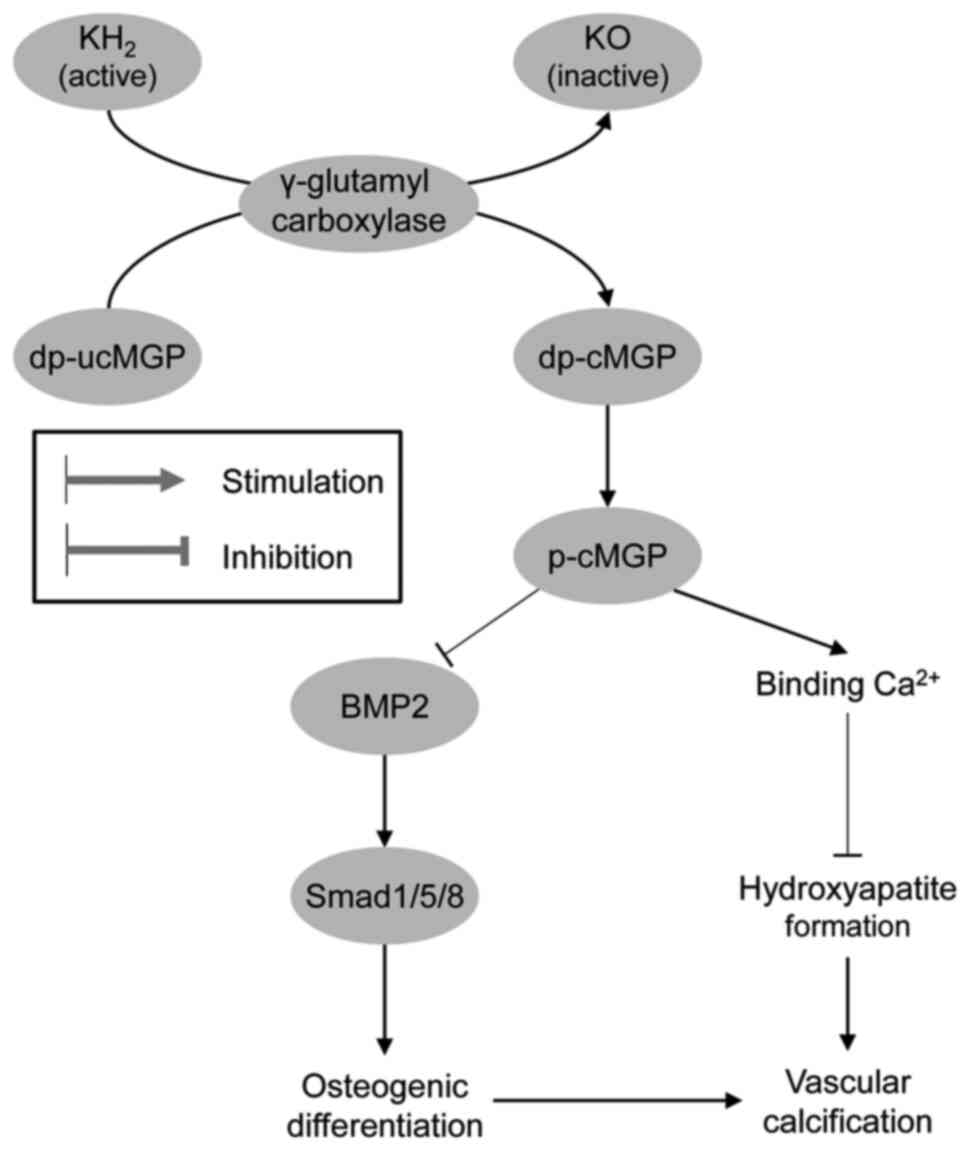

Analogous to OCN, matrix Gla protein has been shown

to be activated by VK-dependent carboxylation and phosphorylation,

exerting a significant inhibitory effect on vascular calcification

(136), and the level of

non-phosphorylated uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein (MGP) may be

considered as a biomarker of VK status (137). Therefore, VK deficiency is

associated with a reduced Ca2+ deposition in bones and

an increase in vascular calcification (138). Menaquinone-4 insufficiency is

also considered as a predictor of aortic calcification (139). Moreover, the administration of

VK antagonists has been shown to significantly increase

dephosphorylated and uncarboxylated matrix Gla protein levels,

which directly correlated with vascular calcification (140). Correspondingly, MK-4 has been

shown to inhibit the osteogenic transdifferentiation of vascular

smooth muscle cells and preserve a contractile phenotype in

spontaneously hypertensive rats (141). Active MGP has been shown to

inhibit osteogenic stimuli by binding to BMP-2 and reducing

mineralization, whereas inactive MGP is unable to inhibit the

osteogenic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells

(142). The protective effects

of VK on vascular calcification may also be mediated by its

influence on Gla-rich protein and growth arrest-specific gene 6

protein expression (143)

(Fig. 2).

Taken together, the existing clinical and laboratory

data demonstrate that VK supplementation effectively improves BMD

and reduces the risk of fractures in post-menopausal women. In

addition it enhances the anti-osteoporotic effects of vitamin D and

Ca2+ supplementation. The osteogenic effect of

VK2 as MK4 and MK7 has been shown to be attributed to

the activation of BMP-2 and Wnt/β-catenin signaling, the promotion

of autophagy and the amelioration of the inhibitory effects of

pro-inflammatory cytokines on SMAD signaling. VK2 also

exerts protective effects in osteoblast culture by preventing

apoptosis and ferroptosis. In addition to the osteogenic effect, it

also inhibits bone resorption by inhibiting osteoclastogenesis and

activation by downregulating RANKL signaling with a shift to OPG

activation. VK has also been shown to prevent vascular

calcification by activating MGP, therefore directing

Ca2+ from the vascular wall to its deposition in bones.

Therefore, VK may be considered protective, not only against

osteoporosis, but also vascular calcification and associated

cardiovascular disease.

Vitamin A (VA) has been shown to be involved in the

regulation of bone physiology through retinoic acid receptor (RAR)

signaling (144), although the

existing data on the association between VA intake or accumulation

and BMD remain controversial due to the distinct effects of

different doses (145).

In osteoporotic untreated post-menopausal women,

serum retinol has been shown to be directly associated with the

risk of low bone mass at the lumbar spine and femoral neck

(146). The association between

high retinol levels and osteoporosis is aggravated in subjects with

vitamin D deficiency (147).

Concomitantly, a U-shaped association between the plasma retinol

concentration and BMD has been observed, with both deficiency and

excess being associated with a lower BMD in children (148). These findings generally

corroborate an observation of improved bone formation following the

reduction of VA in children with high vitamin stores (149). The results of a meta-analysis

demonstrated that the intake of VA and retinol, but not β-carotene,

was associated with the risk of hip fractures, although serum

retinol levels were characterized by a U-shaped association with

the risk of hip fractures (14).

It is noteworthy that, in non-supplemented subjects

with a low dietary VA intake, plasma levels of retinol and

carotenoids were inversely associated with osteoporosis (150,151). Moreover, the maternal plasma

retinol level is directly associated with adult offspring spine BMD

and trabecular bone score following adjustment for multiple

covariates, including vitamin D levels (152).

Recent findings have demonstrated that the

association between the VA status and the risk of fractures as the

outcome of osteoporosis is not significant. Specifically, no

association between high serum retinol levels and an increased risk

of fractures was observed in the elderly involved in Norwegian

Epidemiologic Osteoporosis Studies (153). The results of a meta-analysis

demonstrated that an increased VA intake was not associated with a

risk of fractures (154). No

association between VA intake with BMD or the risk of fractures was

observed in pre-menopausal women with a lower baseline VA intake

level (155). It is proposed

that the association between a high VA intake and an increased risk

of fractures may be mediated by an increased body mass index

(156).

The VA status is also tightly associated with the

dietary intake of provitamin A carotenoids that may also have a

significant effect on bone health (157). A high dietary total carotenoid

intake (Q1 vs. Q4) has been shown to be associated with a 39% lower

risk of hip fractures in males, whereas no association was observed

in females (158). Another

study also demonstrated reduced odds of hip fractures with a high

dietary intake of both total carotenoid and individual β-carotene,

β-cryptoxanthin, and lutein/zeaxanthin intake, while the intake of

α-carotene and lycopene was not associated with the risk of hip

fractures (159).

Correspondingly, a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies

involving 140,265 subjects demonstrated that a high total

carotenoid, as well as β-carotene intake was associated with a 28%

lower risk of hip fractures, while no association between

circulating carotenoid and fracture risk was shown (160). Correspondingly, the

meta-analysis by Gao and Zhao (161) demonstrated a significant

association between the dietary β-carotene intake and a reduction

in the risk of developing osteoporosis.

Serum β-cryptoxanthin, lycopene and α-carotene

levels have been found to be associated with a

concentration-dependent increase in BMD in Chinese adults, with a

more pronounced association in females (162). Correspondingly, in the European

Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC)-Norfolk

cohort, plasma α and β-carotene levels were inversely associated

with a risk of hip fractures in males (163).

These findings demonstrate that VA, as well as

provitamin A carotenoid intake is associated with bone health,

although this association appears to be non-linear. Despite being

rather contradictory, the existing epidemiological data demonstrate

that both the deficiency and excess of VA may promote the risk of

bone loss. The laboratory findings also demonstrate that VA

metabolites may possess distinct effect on mechanisms associated

with bone formation.

A number of studies have demonstrated that the VA

metabolite, ATRA, significantly increases osteoblastogenesis and

osteogenesis. Specifically, in rat bone marrow-derived mesenchymal

stem cells, exposure to 10 μM ATRA was shown to promote

osteogenic differentiation through the pregulation of osteogenic

(ALP, BMP-2, OSX, Runx2, OPN and OCN) and angiogenic [VEGF,

hypoxia-inducible factor-1, Fms related receptor tyrosine kinase 3,

angiotensin (ANG)-2 and ANG-4] gene mRNA expression, while in an

in vivo model, ATRA injection (10 μM, 100 μl)

into the distraction gap significantly improved bone consolidation

and its properties (168). The

administration of 10 μm ATRA has been shown to promote the

Wnt3a-induced osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells

through the activation of PI3K/AKT/GSK3β pathway (169). Both ATRA and 9-cis retinoic

acid at the concentrations of 5-20 μM have been shown to

promote the in vitro osteogenic differentiation induced by

BMP-9 in mesenchymal progenitor cells (170). The osteogenic differentiation

of retinoic acid-treated murine induced pluripotent stem cells has

also shown to be at least partially mediated by Notch signaling

(171).

It has also been demonstrated that ATRA promotes a

shift from adipogenic to osteogenic differentiation. Specifically,

1 μM retinoic acid-induced osteoblastogenesis and the

inhibition of adipogenesis in mesenchymal stem cells have been

shown to be dependent on Smad3 upregulation with the subsequent

replacement of C/EBPβ from the Runx2 promoter (172), in agreement with earlier

observation of the C/EBPβ-induced inhibition of the 1 μM

ATRA-induced osteoblastogenesis in C3H10T1/2 cells (173). It has been also demonstrated

that 1 μM RA promotes BMP-2-induced osteogenesis, while

inhibiting BMP-2-induced adipogenesis with the suppression of

adipogenic transcription factors, PPARγ and C/EBPs, thus being a

key factor regulating the commitment of mesenchymal stem cells into

osteoblasts and adipocytes (174). Moreover, 2.5 μM retinoic

acid has been shown to enhance the osteogenic effect of BMP-2 in

human adipose-derived stem cells (175). ATRA (1 μM) has been

shown to promote the BMP-9-induced osteogenic transdifferentiation

of 3T3-L1 preadipocytes through the activation of BMP/Smad and

Wnt/β-catenin signaling (176).

It has been shown that 1 μM retinoic acid promotes the

BMP-2-induced osteoblastic differentiation of preadipocytes through

BMP-RIA and BMP-RIB signaling (177). Correspondingly, retinoic acid

has been shown to induce the osteogenic differentiation of stromal

cells from both visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue depots

(178). Moreover, as previously

demonstrated, in mouse embryonic fibroblasts, 0.4 μM ATRA

promotes a shift to osteogenesis from rosiglitazone-induced

adipogenic differentiation through the upregulation of Smad1/5/8

phosphorylation and Smad6 expression, resulting in the activation

of BMP/Smad pathway (179). At

the same time, it has also been observed that pharmacological

concentrations of 1-10 μM ATRA inhibit osteoblast

proliferation, while increasing its differentiation (180). However, it is notable that

premature osteoblast-to-preosteocyte transitioning induced by 1

μM ATRA may result in altered bone formation (181).

The osteogenic effects of retinoic acid have also

been shown to be associated with RAR activation. Specifically,

retinoic acid (1 μM) has been shown to promote the

osteogenesis of human induced pluripotent stem cells, a process

dependent on RARa and RARb, but not on RARy signaling (182). Correspondingly, it has been

demonstrated that treatment with 20 μM ATRA increases the

spreading of pre-osteoblasts on bio-inert glass surfaces and its

osteogenic activity through RARα and RARβ signaling (183). At the same time, Karakida et

al (184) demonstrated that

ATRA promoted the osteogenic transdifferentiation of myoblastic

C2C12 cells by BMP-2 in a concentration-dependent manner at a range

of 8-2,000 nM, while this effect was ameliorated by RARγ, but not

RARα or RARβ inhibition.

In contrast to previously discussed observations,

several laboratory studies have demonstrated the inhibitory effects

of ATRA on osteogenesis. In particular, 1 μM ATRA has been

shown to inhibit the osteoblastogenesis of the MC3T3-E1

pre-osteoblast cell line (185). Furthermore, 0.5 μM

retinoic acid has been found to significantly inhibit MC-3T3 cell

mineralization through the increased expression of the Wnt

inhibitors, DKK-1 and DKK-2 (186), resulting in the downregulation

of Wnt signaling (187). It has

also been shown that 1 μM ATRA inhibits osteoblastogenesis

induced by BMP-2, BMP-7 or heterodimer BMP-2/7, with the latter

being a more potent activator as compared to homodimers (188). In addition, the inhibition of

the osteogenic differentiation of mouse embryonic palate

mesenchymal cells by 1 μM ATRA has been shown to be

associated with the inhibition of BMPR-IB and Smad5 mRNA expression

(189,190).

The upregulation of IL-1β expression through NF-κB

activation and inflammasome formation may also contribute to the

anti-osteogenic effects of 1-10 μM ATRA (194). These findings correspond to the

observation that IL-6 overproduction by human osteoblasts occurs

even upon exposure to physiological (10 nM) and higher (up to 10

μM) ATRA concentrations (195).

Taken together, the existing studies demonstrate

that ATRA at various concentrations can both promote and inhibit

osteogenesis, with ATRA at nanomolar concentrations inhibiting, and

at micromolar concentrations activating osteoblasts (15). However, it has been suggested

that the inhibitory effects on osteogenesis occur at higher

exposure levels (196).

Therefore, further studies are required to clarify the

mode-of-action of ATRA in osteogenesis and to provide a solid

rationale for adequate VA intake in vivo.

In addition to its impact on osteoblast physiology,

VA is also involved in the regulation of bone resorption through

the modulation of osteoclast activity. Specifically, retinoic acid

has been shown to increase the proliferation of osteoclast

progenitors, while inhibiting osteoclast differentiation by

suppressing RANK/RANKL signaling (197) with the downregulation of NFATc1

(198), NFAT2, c-Fos and MafB

(199). These effects were

shown to de dependent on RAR activation, with RARα signaling being

the most effective (198). In

another study, 1 μM ATRA significantly inhibited

BMP2/7-induced osteoclastogenesis through the downregulation of

RANK and Nfatc1 expression (200). It is also notable that not only

ATRA, but also 9-cis retinoic acid at a concentration of 1 nM,

significantly inhibited calcitriol-induced bone resorption

(201).

In another study, retinoic acid was shown to

increase periosteal bone resorption by increasing osteoclast

differentiation through the RARα-dependent increase in the

RANKL/OPG ratio (202). The

stimulation of osteoclast activity by retinoic acid was associated

with an increased expression of cathepsin K (203). In addition to osteoclast

activation, retinoic acid-induced bone damage has been shown to be

associated with osteocytic osteolysis, as evidenced by a reduction

in mature osteoblast/osteocyte-specific genes (Bglap2 and Ibsp),

without any significant alteration of Runx2 mRNA expression

(204). Therefore, these

findings demonstrate that analogous to osteoblasts, the effects of

ATRA on osteoclast proliferation, differentiation and functioning

are likely bimodal.

In addition to VA and its metabolites, carotenoids

have also been shown to promote osteoblast proliferation and

differentiation (157).

β-cryptoxanthin has been shown to exert osteoprotective effects by

promoting osteoblastogenesis and inhibiting osteoclastic bone

resorption (205). It has been

shown that β-cryptoxanthin significantly increases the osteoblastic

differentiation of MC3T3-E1 cells with a significant increase in

Runx2 mRNA expression (206).

β-cryptoxanthin-induced osteoblast differentiation has been shown

to be mediated by the activation of TGF-β1-induced Smad activation,

being independent of BMP2-Smad signaling (207). Both β-cryptoxanthin and

p-hydroxycinnamic acid have been shown to inhibit basal NF-κB

activity in MC3T3 pre-osteoblasts, whereas only p-hydroxycinnamic

acid significantly suppresses TNF-induced NF-κB activity (208). p-Hydroxycinnamic acid

ameliorates inhibitory effects of TNF-α-induced NF-κB signaling on

Smad-mediated TGF-β and BMP-2 signaling (209).

Osteoclastogenesis is also considered as the target

for carotenoid effects on bone health. Specifically, it has been

shown that 0.1-1 μM β-cryptoxanthin significantly inhibits

PTH, PGE2-, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-, lipopolysaccharide-, or

TNFα-induced osteoclastogenesis through the downregulation of RANKL

and M-CSF signaling (217). The

downregulation of RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis by 5 μM

β-cryptoxanthin has been shown to be dependent on the suppression

of the inhibitor of NF-κB kinase β (IKK β) activity, suppressing

NF-κB activation (218). The

anti-osteoclastogenic effect of β-cryptoxanthin has also been shown

to b associated with the promotion of caspase-3-mediated apoptosis

(219). Correspondingly, in

another study, dietary β-cryptoxanthin intake prevented

osteoclastic bone resorption in ovariectomized mice through

interference with the RANKL pathway (220). A similar protective effect was

observed against inflammatory bone resorption in a mouse model of

periodontitis (221).

In addition to β-cryptoxanthin, other carotenoids

have also been shown to modulate osteoclast functioning. It has

been shown that β-carotene (0.2 μM) significantly

ameliorates RANKL-induced NFATc1, c-Fos and CTSK expression, as

well as osteoclastic bone resorption through the inhibition of IκB

phosphorylation, whereas ERK, JNK and p38 expression remain

unaltered (222). Similarly, 50

μg/ml astaxanthin has been shown to inhibit

Nε-carboxymethyllysine-induced osteoclastogenesis

through the inhibition of NF-κB activation and subsequent

downregulation of NFATc1 expression (223). In bone marrow cells, treatment

with 30 μM lutein was shown to inhibit IL-1-induced

RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis, while promoting osteogenesis in

an osteoblast culture by increasing BMP-2 and decreasing sclerostin

mRNA expression (224).

The role of VA in osteoporosis thus appears

unclear. While multiple studies have demonstrated that the

excessive dietary intake of VA and its accumulation in the organism

is associated with a reduced BMD and osteoporosis, observations in

children and VA-depleted subjects have demonstrated that its

deficiency may also exert adverse effects on bone physiology. In

vivo studies have demonstrated adverse effects of the excessive

VA intake on bone health, while in vitro studies have been

inconsistent with the epidemiological findings, indicating positive

effects of VA at micromolar doses on osteogenesis, whereas lower

nanomolar doses exert inhibitory effects. Specifically, it has been

demonstrated that the effects of VA on bone formation are mediated

by the modulation of BMP-2 and Wnt/β-catenin-mediated osteogenesis.

Other targets for the effects of VA in bones include the GH/IGF-1

axis, RAR and Notch signaling, as well as the modulation of

NF-κB-mediated inflammation. Similarly, the effects of VA on

osteoclast formation and activity vary significantly from

inhibition to stimulation, due to the differential modulation of

RANKL signaling. These findings demonstrate that VA intake needs to

be carefully monitored in subjects who are at risk in order to

avoid the hazardous effects of both hypo- and hypervitaminosis on

bone health.

VC plays a crucial role in bone physiology,

exerting beneficial effects on trabecular bone formation, thereby

being considered as a potential treatment modality for osteoporosis

(226).

VC supplementation in post-menopausal women has

been shown to be associated with an almost 3% increase in BMD in

multiple sites, while the highest BMD was observed in women using

VC, estrogen and Ca2+ (227). A higher VC intake has also been

shown to be associated with a 33% lower risk of developing

osteoporosis (228).

These findings corroborate the results of a more

recent meta-analysis, demonstrating that a higher frequency of

dietary VC intake was associated with a 34% lower prevalence of hip

fractures (229). It has been

shown that a 50 mg/day increase in VC intake is associated with a

5% decrease in the risk of hip fractures (230). The results of a 17-year

follow-up demonstrated that VC supplementation resulted in lower

rates of hip fractures (231).

The results from the KNHANES IV (2009) study demonstrated a

significant association between dietary VC intake and BMD only in

vitamin D-deficient elderly individuals (232).

Epidemiological findings have also demonstrated a

positive association between VC intake, circulating ascorbate

levels and BMD (233). In turn,

a suboptimal plasma VC level is considered as a significant

predictor of a low BMD in males (234). Despite the lack of significant

effects of dietary VC intake, a normal plasma VC concentration has

been shown to be associated with a higher BMD in post-menopausal

Puerto Rican women without estrogen therapy (235).

The promotion of bone formation by VC appears to be

mediated by the modulatory effects of VC on osteoblast

differentiation and activity. Specifically, VC significantly

increases osteoblast differentiation in a suspension of mononuclear

cells (242), in association

with increased type I collagen production and extracellular matrix

mineralization (243). VC

promotes both the proliferation and osteoblastic differentiation of

MC3T3-E1 type pre-osteoblast cells (244). VC-induced osteogenic

differentiation has been shown to affect the expression of

>15,000 genes that are related to cell growth, morphogenesis,

metabolism, cell communication and cell death in addition to

osteoblast-specific genes (245). It is also notable that VC

increases the phosphate-induced osteoblastic transformation of

vascular smooth muscle cells by promoting intracellular

Ca2+ deposition (246), thus increasing the risk of

vascular calcification.

It has been demonstrated that low doses of VC

significantly promote osteoblast differentiation through the

upregulation of RUNX2 and SPP1 gene expression in MG-63 cells,

whereas high doses of VC induce apoptotic cell death (247). The osteogenic effects of VC

have been shown to involve the activation of BMP-2 and

Wnt/β-Catenin/ATF4 signaling (248). VC also reduces the number of

senescent cells by increasing the proportion of cells with

proliferative capacity (249).

The activation of casein kinase 2 involved in the regulation of

bone formation may also be involved in the osteogenic effects of

ascorbate osteoblast-like (MG63) cells (250). Osteoblastogenesis has been

shown to be mediated by VC-induced OSX expression through the

activation of PHD and subsequent proteasomal degradation of OSX

gene transcriptional repressors (251). The activation of osteogenesis

by VC has been shown to involve its direct interaction with PHD2

(252).

The osteogenic effects of VC are also dependent on

microtubule plus-end-binding protein 1 expression with the

subsequent activation of β-catenin expression (253). Of note, VC has been found to

exert osteogenic effects at the beginning of bone formation,

although at later periods (9 days) it may exert adverse effects

(254). It has also been

demonstrated that VC induces a shift to osteogenesis and myogenesis

from adipogenesis in mesoderm-derived stem cells, at least

partially through the p38MAPK/CREB pathway (255). A similar effect mediated by the

depletion of the cAMP pool was observed in the OP9 mesenchymal cell

line (256).

Ascorbic acid 2-phosphate, a long-acting VC

derivative, has been shown to promote osteoblast differentiation,

in contrast to the inhibitory effects of VC in a culture of MG-63

cells (257). Correspondingly,

ascorbate-2-phosphate has been shown to increase the expression of

MMP-2 and MMP-13, whereas the ascorbic acid-induced expression of

membrane type1-MMP has been observed only at the early stages of

differentiation (258).

Epigenetic mechanisms may also underlie the

modulatory effects of VC on osteogenesis. Specifically, VC-induced

osteogenic differentiation is tightly associated with H3K9me3 and

H3K27me3 demethylation and 5-hydroxy-methyl-cytosine levels

(259).

VC also significantly modulates bone resorption

through the regulation of osteoclastogenesis and osteoclast

activity. Specifically, VC has been shown to reduce RANKL-induced

osteoclastogenesis in vitro (260) through the redox-dependent

inhibition of NF-κB signaling (261). Correspondingly, it has been

shown that VC significantly inhibits the RANKL and NF-κB

expression-associated increase in osteoclast differentiation in

rats fed a high-cholesterol diet (262). In turn, VC deficiency has been

shown to increase bone resorption and osteoclastogenesis via the

ERK-dependent upregulation of RANK, c-jun and c-fos expression

(263).

VC has also been shown to be essential for

appropriate osteoclastogenesis by increasing RANKL mRNA expres-

sion (264,265). VC has been shown to be

essential for osteoclast differentiation by increasing

preosteoclast maturation and improvement in cell viability

(266). In addition, VC

promotes glycerophosphate-induced osteoclast differentiation by

increasing RANKL-induced NFATc1, c-fos and COX-1 expression

(267). It is notable that VC

promotes osteoclast formation only at earlier stage of

osteoclastogenesis, whereas at the late stage, it increases

osteoclast death (268).

The existing epidemiological studies demonstrate

that a higher VC intake is associated with a lower risk of

osteoporosis and fractures, that may be mediated by the osteogenic

effects of VC via the activation of BMP-2 and Wnt/β-catenin

signaling. Epigenetic effects may also underlie the positive

effects of VC on osteoblast differentiation. Despite the

observation of inhibitory effects of VC on RANKL and

NF-κB-associated osteoclastogenesis, VC has been shown to be

essential for appropriate osteoclast formation.

Group B vitamins represent a group of structurally

heterogeneous water-soluble molecules performing cofactor roles for

a plethora of enzymes involved in human energy metabolism (269), including bone physiology and

protection against osteoporosis (270). However, certain contradictions

regarding the protective effects of group B vitamins exist

(271).

An analysis of the Framingham Offspring

Osteoporosis Study (1996-2001) data demonstrated that males and

females with plasma vitamin B12 levels <148 pM are

characterized by decreased hip and spine BMD, respectively

(271). Correspondingly, an

insufficient B12 intake has been considered as a risk

factor for osteoporosis in vegans (272). A meta-analysis study by Zhang

et al (273)

demonstrated that both homocysteine (Hcy) and B12 levels

were found to be elevated in post-menopausal osteoporotic women. In

addition, in Moroccan women, plasma B12 levels, as well

as the circulating Hcy concentration, were inversely associated

with hip BMD (274).

Folic acid levels have been found to be

significantly associated with BMD following adjustment for Hcy

concentrations and other confounders (278). It is considered that

supplementation with folic acid at a dose of 0.5-5 mg may be useful

for the improvement of BMD in patients with low folic acid levels

or hyperhomocysteinemia (279).

Several studies have investigated combined group B

vitamin supplementation. It was previously demonstrated shown that

the 2-year group B vitamin (folic acid, B6,

B12, B2) supplementation in subjects with a

low B12 status prevented a significant reduction in BMD

at the femoral neck and hip (280). In turn, circulating plasma

folic acid and B12 levels have been shown to be directly associated

with BMD and bone strength in post-menopausal Chinese-Singaporean

women, respectively (281). Low

serum folic acid and B6, but not B12 levels,

have been shown to be associated with lower bone trabecular number

and thickness in subjects who underwent hip arthroplasty (282).

The results of a recent meta-analysis demonstrated

that severe folic acid, but not B6 or B12 deficiency, was

associated with an increased risk of fractures in the elderly

(283). Other studies have

failed to reveal an association between serum B12 or

folic acid levels with BMD (284,285) or the vertebral fracture rate

(286), although a reduction in

the Hcy concentration has been observed (287).

Hcy affects the efficacy of group B vitamin

supplementation. Specifically, although long-term vitamin

B12 and folic acid supplementation do not reduce the

risk of osteoporotic fractures (288) or improve BMD (289), in the general cohort of the

B-PROOF trial, vitamin supplementation reduced the number of

fractures in subjects with hyperhomocysteinemia (288). Nonetheless, no effect of folic

acid, vitamin B6 and B12 supplementation on

fracture risk or bone turnover biomarkers in hyperhomocysteinemic

subjects has been observed (290).

Genetic factors also significantly modulate the

association between the group B vitamin status and bone health. Ahn

et al (291)

demonstrated that 3'-UTR polymorphisms of vitamin B-related genes,

transcobalamin II, reduced folate carrier protein 1 and thiamine

carrier 1, and particularly CD320 (transcobalamin II receptor),

were associated with osteoporosis and osteoporotic spinal fractures

in post-menopausal women. The association between vitamin B levels

and BMD was also shown to be modified by genetic variants in the

1-carbon methylation pathway (292).

Laboratory studies have also demonstrated that

group B vitamins have a significant impact on bone physiology and

osteoporosis. Specifically, folic acid has been shown to

significantly improve bone architecture and prevent bone loss

through the reduction of osteoclast number via AMPK activation and

the upregulation of Nrf2 signaling in high-fat diet-induced

osteoporosis (293). It has

been shown that folic acid supplementation significantly reduces

the inhibitory effects of dexamethasone on vertebral osteogenesis

through the upregulation of the TGF-β signaling pathway, with a

subsequent increase in p-Smad2/3, Runx2 and Osterix expression in

chick embryos (294). Similar

beneficial effect of FA supplementation on bone density was

observed in a model of cyclosporine-induced bone loss (295). Folic acid also ameliorated the

adverse effect of homocysteine on osteoblast proliferation,

differentiation and mineralization through inhibition of

PERK-activated ERS (296).

Folic acid potentiated osteoblastogenic effect of hydroxyapatite

nanoparticles, as evidenced by a more profound RUNX2 expression in

human mesenchymal stem cells (297). At the same time, high maternal

folic acid intake was shown to reduce BMD in the offspring

(298).

Taken together, although B group vitamins have been

shown to play a crucial role in bone physiology, as demonstrated in

deficiency models, epidemiological data on the efficiency of

vitamin supplementation are inconclusive. However, the beneficial

effects of folic acid and B12 supplementation on bone

quality have been reported to be critical in subjects with

insufficient vitamin intake.

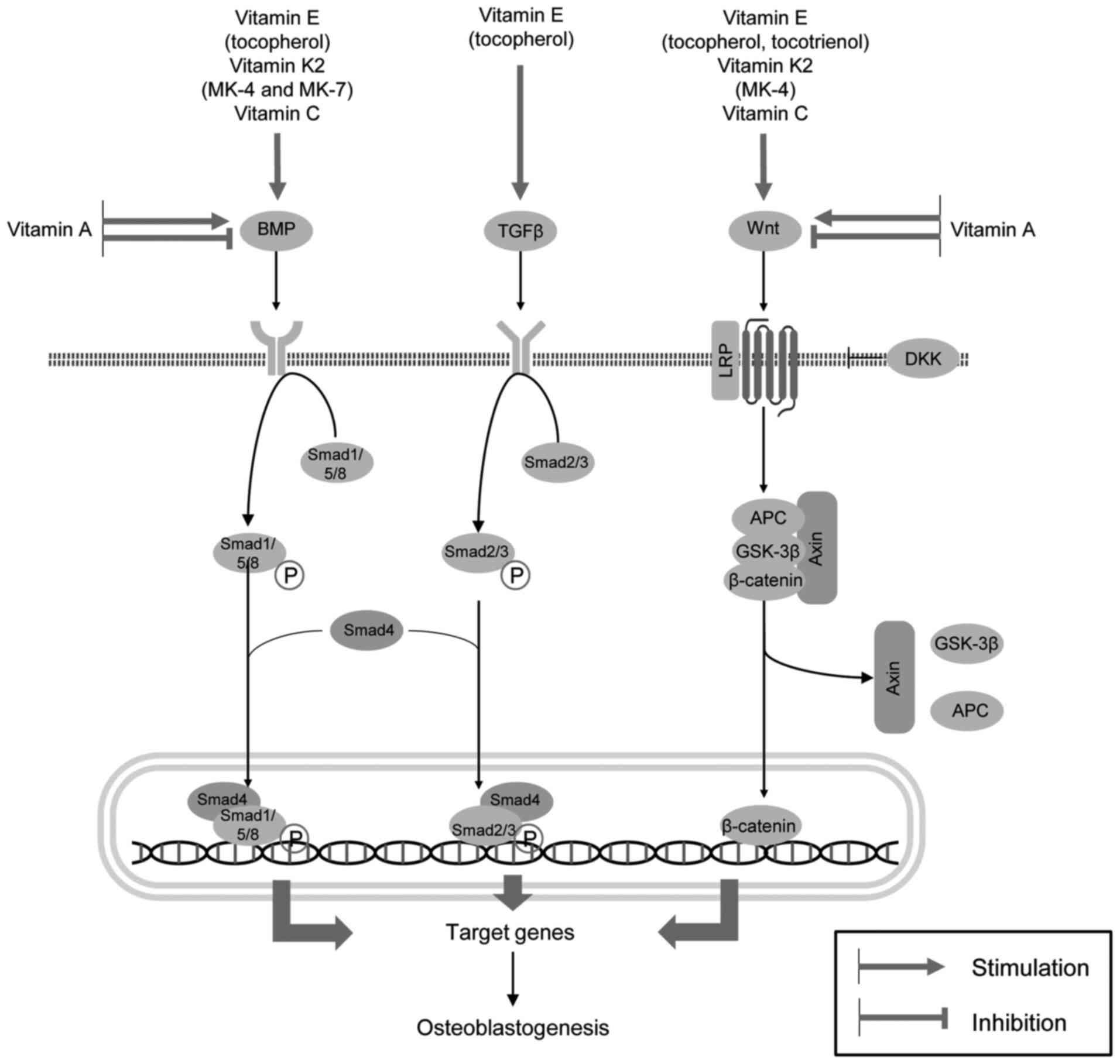

Existing data demonstrate that an adequate vitamin

intake is essential for bone health, while vitamin deficiency is

associated with an increased risk of developing osteoporosis.

Specifically, the intake of vitamins E, K2 and C has

been shown to be associated with increased BMD and a reduced risk

of fractures. In turn, the excessive intake of vitamins can also

have adverse effect on bone health and osteoporosis, as clearly

demonstrated for VA. The observed effects of vitamins on the risk

of osteoporosis have been shown to be mediated via mechanisms that

regulate bone formation and resorption. VE (tocopherols and

tocotrienols), VK2 (menaquinones 4 and 7) and VC have

been shown to promote osteoblast development via the upregulation

of BMP/Smad and Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Tocopherol also

contributes to osteoblastogenesis through the stimulation of the

TGFβ/Smad pathway. The VA metabolite (ATRA) appears to exert both

inhibitory and stimulatory effects on BMP- and

Wnt/β-catenin-mediated osteogenesis at nanomolar and micromolar

concentrations, respectively (Fig.

3). However, these observations are contradictory to those of

epidemiological studies demonstrating adverse effects of the

excessive intake of VA on bone health. In addition to these

mechanisms, the upregulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling, the

inhibition of osteoblast apoptosis and ferroptosis, the improvement

of redox homeostasis through SIRT1/Nrf2 and other pathways, as well

as the inhibition of NF-κB signaling, may contribute to higher

osteoblast viability and osteogenesis. In addition, the osteogenic

effects of certain vitamins have been shown to be mediated by the

modulation of the effects of hormones, including insulin, GH and

PTH on bone physiology.

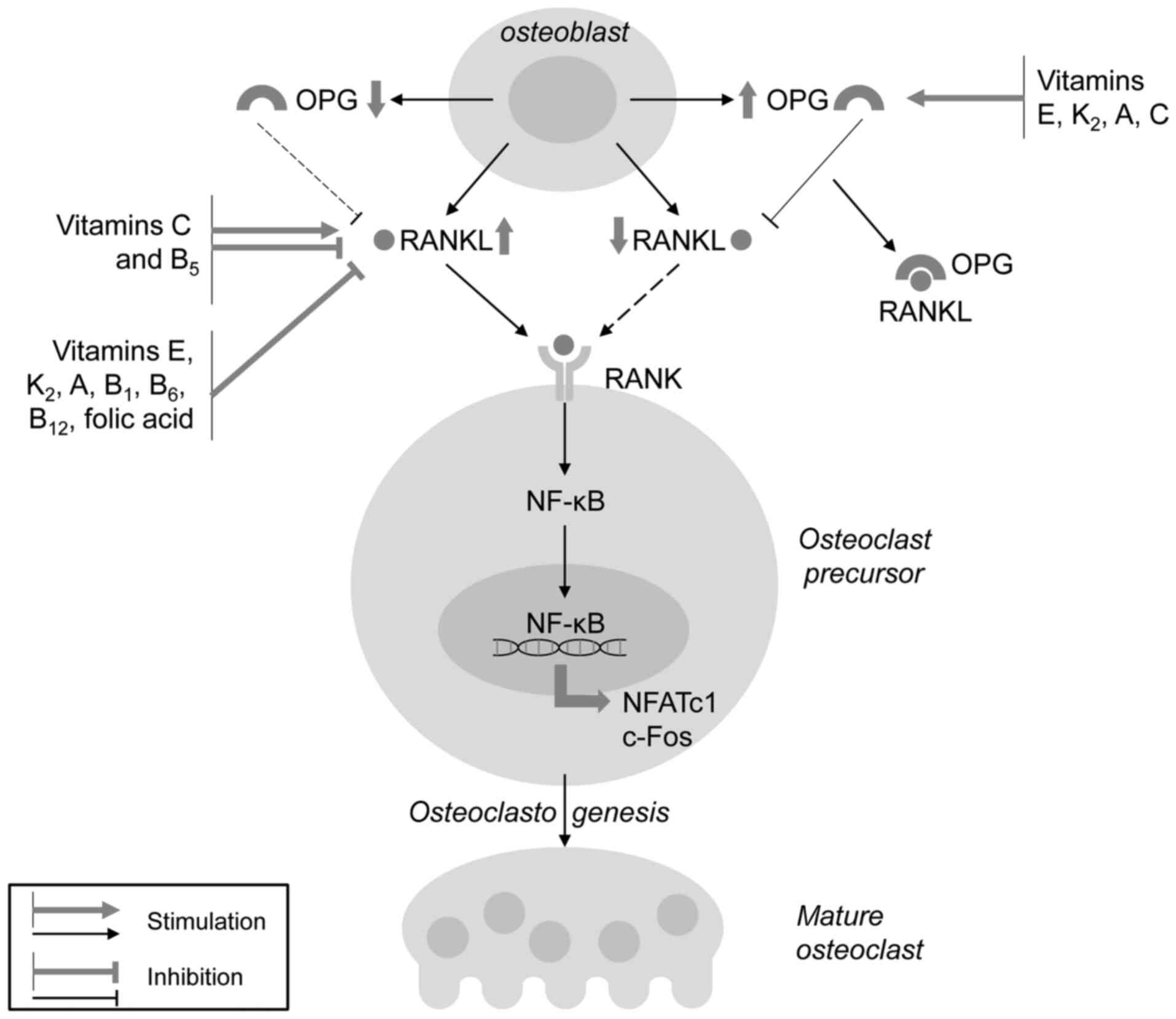

In addition to increased osteoblast proliferation

and differentiation, vitamins are involved in the regulation of

bone resorption through the modulation of osteoclast development

and activity (Fig. 4), thus

increasing the ratio between osteoblast and osteoclast activity.

Both lipid-soluble vitamins E, K2, A, and water-soluble

vitamins B1, B6, B12, C and folic

acid significantly reduce RANKL production, thus reducing the

RANKL/OPG ratio and RANKL/RANK signaling with a subsequent

anti-osteoclastogenic effect. Notably, VC has been shown to be

essential for osteoclast development, and its effect on

osteoclastogenesis has been shown to be dependent on the dose and

the stage of cell development, as also observed for vitamin

B5. In addition, VK2 has been shown to

prevent vascular calcification by activating MGP through its

carboxylation, thereby directing Ca from the vascular wall to its

deposition in bones.

In view of the epidemiological and laboratory

findings, it appears that antioxidant group E vitamins,

particularly in the form of α-tocopherol and VC should be

considered as effective micronutrients for the reduction of

osteoporosis and to lower the risk of adverse effects. Although

VK2 exerts a positive effect on bone formation through

the modulation of both osteoblast and osteoclast activity, as well

as a reduction in vascular calcification and the promotion of

calcium deposition in bones, its intake should be closely monitored

in subjects at a higher risk of hypercoagulation due to its role in

blood clotting. It appears that the therapeutic window of VA for

improved bone health and quality is rather narrow, and both

insufficient and excessive VA intake reduces bone quality; thus, it

should be supplemented only in subjects with VA deficiency. The

beneficial effects of folic acid and B12 supplementation

on bone health are also likely to be inherent to subjects with

insufficient vitamin intake, thus maintaining optimal B group

vitamin dietary intake is also essential for prevention of

osteoporosis. In view of the existing data, further studies are

required to unravel the effects and mechanisms underlying the

impact of various forms and doses of vitamins on bone physiology,

as well as dependence of these effects on baseline vitamin

status.

Not applicable.

AVS, MA and AAT were involved in the

conceptualization of the study. MA, AT, JBTR, AS, DAS, ACM, RL,

TVK, WC, JSC, JCJC and CL were involved the investigation/search of

the literature for the purposes of the review. MA, AT, JBTR, AS,

DAS, ACM, RL, TVK, WC, JSC, JCJC, CL and AAT were involved in the

data curation. AAT was involved in figure preparation. ACM, RL,

TVK, WC, JSC, JCJC, CL and AAT were involved in the writing and

preparation of the original draft. AVS, MA, AT, JBTR, AS and DAS

were involved in the writing, reviewing and editing of the

manuscript. AVS and MA supervised the study. All authors have read

and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

DAS is the Editor-in-Chief for the journal, but had

no personal involvement in the reviewing process, or any influence

in terms of adjudicating on the final decision, for this article.

The other authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the RUDN University Strategic

Academic Leadership Program (award no. 202713-0-000 'Development of

a scientifically based methodology for the ecological adaptation of

foreign students to the new environmental conditions').

|

1

|

Lorentzon M and Cummings SR: Osteoporosis:

The evolution of a diagnosis. J Intern Med. 277:650–661. 2015.

|

|

2

|

Salari N, Ghasemi H, Mohammadi L, Behzadi

MH, Rabieenia E, Shohaimi S and Mohammadi M: The global prevalence

of osteoporosis in the world: A comprehensive systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 16:6092021.

|

|

3

|

Xiao PL, Cui AY, Hsu CJ, Peng R, Jiang N,

Xu XH, Ma YG, Liu D and Lu HD: Global, regional prevalence, and

risk factors of osteoporosis according to the World Health

Organization diagnostic criteria: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 33:2137–2153. 2022.

|

|

4

|

Clynes MA, Harvey NC, Curtis EM, Fuggle

NR, Dennison EM and Cooper C: The epidemiology of osteoporosis. Br

Med Bull. 133:105–117. 2020.

|

|

5

|

Pouresmaeili F, Kamalidehghan B, Kamarehei

M and Goh YM: A comprehensive overview on osteoporosis and its risk

factors. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 14:2029–2049. 2018.

|

|

6

|

Levis S and Lagari VS: The role of diet in

osteoporosis prevention and management. Curr Osteoporos Rep.

10:296–302. 2012.

|

|

7

|

Muñoz-Garach A, García-Fontana B and

Muñoz-Torres M: Nutrients and dietary patterns related to

osteoporosis. Nutrients. 12:19862020.

|

|

8

|

Brincat M, Gambin J, Brincat M and

Calleja-Agius J: The role of vitamin D in osteoporosis. Maturitas.

80:329–332. 2015.

|

|

9

|

Goltzman D: Functions of vitamin D in

bone. Histochem Cell Biol. 149:305–312. 2018.

|

|

10

|

Ratajczak AE, Rychter AM, Zawada A,

Dobrowolska A and Krela-Kaźmierczak I: Do only calcium and vitamin

D matter? Micronutrients in the diet of inflammatory bowel diseases

patients and the risk of osteoporosis. Nutrients. 13:5252021.

|

|

11

|

Martiniakova M, Babikova M, Mondockova V,

Blahova J, Kovacova V and Omelka R: The role of macronutrients,

micronutrients and flavonoid polyphenols in the prevention and

treatment of osteoporosis. Nutrients. 14:5232022.

|

|

12

|

Heaney RP: Nutrition and risk for

osteoporosis. Osteoporosis. Acadmic Press; pp. 669–700. 2001

|

|

13

|

Nazrun AS, Norazlina M, Norliza M and

Nirwana SI: Comparison of the effects of tocopherol and tocotrienol

on osteoporosis in animal models. Int J Pharmacol. 6:561–568.

2010.

|

|

14

|

Wu AM, Huang CQ, Lin ZK, Tian NF, Ni WF,

Wang XY, Xu HZ and Chi YL: The relationship between vitamin A and

risk of fracture: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Bone

Miner Res. 29:2032–2039. 2014.

|

|

15

|

Henning P, Conaway HH and Lerner UH:

Retinoid receptors in bone and their role in bone remodeling. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 6:312015.

|

|

16

|

Ahmadieh H and Arabi A: Vitamins and bone

health: Beyond calcium and vitamin D. Nutr Rev. 69:584–598.

2011.

|

|

17

|

Szewczyk K, Chojnacka A and Górnicka M:

Tocopherols and tocotrienols-bioactive dietary compounds; What is

certain, what is doubt? Int J Mol Sci. 22:62222021.

|

|

18

|

Wong SK, Mohamad NV, Ibrahim N', Chin KY,

Shuid AN and Ima-Nirwana S: The molecular mechanism of vitamin E as

a bone-protecting agent: A review on current evidence. Int J Mol

Sci. 20:14532019.

|

|

19

|

Michaëlsson K and Larsson SC: Circulating

alpha-tocopherol levels, bone mineral density, and fracture:

Mendelian randomization study. Nutrients. 13:19402021.

|

|

20

|

Mata-Granados JM, Cuenca-Acebedo R, Luque

de Castro MD and Quesada Gómez JM: Lower vitamin E serum levels are

associated with osteoporosis in early postmenopausal women: A

cross-sectional study. J Bone Miner Metab. 31:455–460. 2013.

|

|

21

|

Holvik K, Gjesdal CG, Tell GS, Grimnes G,

Schei B, Apalset EM, Samuelsen SO, Blomhoff R, Michaëlsson K and

Meyer HE: Low serum concentrations of alpha-tocopherol are

associated with increased risk of hip fracture. A NOREPOS study.

Osteoporos Int. 25:2545–2554. 2014.

|

|

22

|

Michaëlsson K, Wolk A, Byberg L, Ärnlöv J

and Melhus H: Intake and serum concentrations of α-tocopherol in

relation to fractures in elderly women and men: 2 Cohort studies.

Am J Clin Nutr. 99:107–114. 2014.

|

|

23

|

Shen CL, Yang S, Tomison MD, Romero AW,

Felton CK and Mo H: Tocotrienol supplementation suppressed bone

resorption and oxidative stress in postmenopausal osteopenic women:

A 12-week randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled trial.

Osteoporos Int. 29:881–891. 2018.

|

|

24

|

Vallibhakara SAO, Nakpalat K,

Sophonsritsuk A, Tantitham C and Vallibhakara O: Effect of vitamin

E supplement on bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteopenic

women: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial.

Nutrients. 13:42262021.

|

|

25

|

Yang TC, Duthie GG, Aucott LS and

Macdonald HM: Vitamin E homologues α- and γ-tocopherol are not

associated with bone turnover markers or bone mineral density in

peri-menopausal and post-menopausal women. Osteoporos Int.

27:2281–2290. 2016.

|

|

26

|

Zhang J, Hu X and Zhang J: Associations

between serum vitamin E concentration and bone mineral density in

the US elderly population. Osteoporos Int. 28:1245–1253. 2017.

|

|

27

|

Hampson G, Edwards S, Sankaralingam A,

Harrington DJ, Voong K, Fogelman I and Frost ML: Circulating

concentrations of vitamin E isomers: Association with bone turnover

and arterial stiffness in post-menopausal women. Bone. 81:407–412.

2015.

|

|

28

|

Hamidi MS, Corey PN and Cheung AM: Effects

of vitamin E on bone turnover markers among US postmenopausal

women. J Bone Miner Res. 27:1368–1380. 2012.

|

|

29

|

Mehat MZ, Shuid AN, Mohamed N, Muhammad N

and Soelaiman IN: Beneficial effects of vitamin E isomer

supplementation on static and dynamic bone histomorphometry

parameters in normal male rats. J Bone Miner Metab. 28:503–509.

2010.

|

|

30

|

Muhammad N, Luke DA, Shuid AN, Mohamed N

and Soelaiman IN: Two different isomers of vitamin E prevent bone

loss in postmenopausal osteoporosis rat model. Evid Based

Complement Alternat Med. 2012:1615272012.

|

|

31

|

Chin KY, Gengatharan D, Mohd Nasru FS,

Khairussam RA, Ern SL, Aminuddin SA and Ima-Nirwana S: The effects

of annatto tocotrienol on bone biomechanical strength and bone

calcium content in an animal model of osteoporosis due to

testosterone deficiency. Nutrients. 8:8082016.

|

|

32

|

Shuid AN, Mohamad S, Muhammad N, Fadzilah

FM, Mokhtar SA, Mohamed N and Soelaiman IN: Effects of α-tocopherol

on the early phase of osteoporotic fracture healing. J Orthop Res.

29:1732–1738. 2011.

|

|

33

|

Mohamad S, Shuid AN, Mohamed N, Fadzilah

FM, Mokhtar SA, Abdullah S, Othman F, Suhaimi F, Muhammad N and

Soelaiman IN: The effects of alpha-tocopherol supplementation on

fracture healing in a postmenopausal osteoporotic rat model.

Clinics (São Paulo). 67:1077–1085. 2012.

|

|

34

|

Akçay H, Kuru K, Tatar B and Şimşek F:

Vitamin E promotes bone formation in a distraction osteogenesis

model. J Craniofac Surg. 30:2315–2318. 2019.

|

|

35

|

Kurklu M, Yildiz C, Kose O, Yurttas Y,

Karacalioglu O, Serdar M and Deveci S: Effect of alpha-tocopherol

on bone formation during distraction osteogenesis: A rabbit model.

J Orthop Traumatol. 12:153–158. 2011.

|

|

36

|

Hagan ML, Bahraini A, Pierce JL, Bass SM,

Yu K, Elsayed R, Elsalanty M, Johnson MH, McNeil A, McNeil PL and

McGee-Lawrence ME: Inhibition of osteocyte membrane repair activity

via dietary vitamin E deprivation impairs osteocyte survival.

Calcif Tissue Int. 104:224–234. 2019.

|

|

37

|

Turan B, Can B and Delilbasi E: Selenium

combined with vitamin E and vitamin C restores structural

alterations of bones in heparin-induced osteoporosis. Clin

Rheumatol. 22:432–436. 2003.

|

|

38

|

Ikegami H, Kawawa R, Ichi I, Ishikawa T,

Koike T, Aoki Y and Fujiwara Y: Excessive vitamin E intake does not

cause bone loss in male or ovariectomized female mice fed normal or

high-fat diets. J Nutr. 147:1932–1937. 2017.

|

|

39

|

Kasai S, Ito A, Shindo K, Toyoshi T and

Bando M: High-dose α-tocopherol supplementation does not induce

bone loss in normal rats. PLoS One. 10:e01320592015.

|

|

40

|

Lan D, Yao C, Li X, Liu H, Wang D, Wang Y

and Qi S: Tocopherol attenuates the oxidative stress of BMSCs by

inhibiting ferroptosis through the PI3k/AKT/mTOR pathway. Front

Bioeng Biotechnol. 10:9385202022.

|

|

41

|

Ahn KH, Jung HK, Jung SE, Yi KW, Park HT,

Shin JH, Kim YT, Hur JY, Kim SH and Kim T: Microarray analysis of

gene expression during differentiation of human mesenchymal stem

cells treated with vitamin E in vitro into osteoblasts. Korean J

Bone Metab. 18:23–32. 2011.

|

|

42

|

Jia YB, Jiang DM, Ren YZ, Liang ZH, Zhao

ZQ and Wang YX: Inhibitory effects of vitamin E on osteocyte

apoptosis and DNA oxidative damage in bone marrow hemopoietic cells

at early stage of steroid-induced femoral head necrosis. Mol Med

Rep. 15:1585–1592. 2017.

|

|

43

|

Soeta S, Higuchi M, Yoshimura I, Itoh R,

Kimura N and Aamsaki H: Effects of vitamin E on the osteoblast

differentiation. J Vet Med Sci. 72:951–957. 2010.

|

|

44

|

Kim HN, Lee JH, Jin WJ and Lee ZH:

α-Tocopheryl succinate inhibits osteoclast formation by suppressing

receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand (RANKL)

expression and bone resorption. J Bone Metab. 19:111–120. 2012.

|

|

45

|

Johnson SA, Feresin RG, Soungdo Y, Elam ML

and Arjmandi BH: Vitamin E suppresses ex vivo osteoclastogenesis in

ovariectomized rats. Food Funct. 7:1628–1633. 2016.

|

|

46

|

Fujita K, Iwasaki M, Ochi H, Fukuda T, Ma

C, Miyamoto T, Takitani K, Negishi-Koga T, Sunamura S, Kodama T, et

al: Vitamin E decreases bone mass by stimulating osteoclast fusion.

Nat Med. 18:589–594. 2012.

|

|

47

|

Chin KY and Ima-Nirwana S: The biological

effects of tocotrienol on bone: A review on evidence from rodent

models. Drug Des Devel Ther. 9:2049–2061. 2015.

|

|

48

|

Shen CL, Klein A, Chin KY, Mo H, Tsai P,

Yang RS, Chyu MC and Ima-Nirwana S: Tocotrienols for bone health: A

translational approach. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1401:150–165. 2017.

|

|

49

|

Xu W, He P, He S, Cui P, Mi Y, Yang Y, Li

Y and Zhou S: Gamma-tocotrienol stimulates the proliferation,

differentiation, and mineralization in osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells.

J Chem. 2018:38059322018.

|

|

50

|

Wan Hasan WN, Abd Ghafar N, Chin KY and

Ima-Nirwana S: Annatto-derived tocotrienol stimulates osteogenic

activity in preosteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells: A temporal sequential

study. Drug Des Devel Ther. 12:1715–1726. 2018.

|

|

51

|

Wan Hasan WN, Chin KY, Abd Ghafar N and

Soelaiman IN: Annatto-derived tocotrienol promotes mineralization

of MC3T3-E1 cells by enhancing BMP-2 protein expression via

inhibiting RhoA activation and HMG-CoA reductase gene expression.

Drug Des Devel Ther. 14:969–976. 2020.

|

|

52

|

Xu W, Li Y, Feng R, He P and Zhang Y:

γ-Tocotrienol induced the proliferation and differentiation of

MC3T3-E1 cells through the stimulation of the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway. Food Funct. 13:398–410. 2022.

|

|

53

|

Shah AK and Yeganehjoo H: The stimulatory

impact of d-δ-Tocotrienol on the differentiation of murine MC3T3-E1

preosteoblasts. Mol Cell Biochem. 462:173–183. 2019.

|

|

54

|

Casati L, Pagani F, Maggi R, Ferrucci F

and Sibilia V: Food for bone: Evidence for a role for

delta-tocotrienol in the physiological control of osteoblast

migration. Int J Mol Sci. 21:46612020.

|

|

55

|

Abd Manan N, Mohamed N and Shuid AN:

Effects of low-dose versus high-dose γ-tocotrienol on the bone

cells exposed to the hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress and

apoptosis. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012:6808342012.

|

|

56

|

Casati L, Pagani F, Limonta P, Vanetti C,

Stancari G and Sibilia V: Beneficial effects of δ-tocotrienol

against oxidative stress in osteoblastic cells: Studies on the

mechanisms of action. Eur J Nutr. 59:1975–1987. 2020.

|

|

57

|

Cai J, Tian X, Ren J, Lu S and Guo J:

Synergistic effect of sesamin and γ-Tocotrienol on promoting

osteoblast differentiation via AMPK signaling. Nat Prod Commun.

17:1–8. 2022.

|

|

58

|

Radzi NFM, Ismail NAS and Alias E:

Tocotrienols regulate bone loss through suppression on osteoclast

differentiation and activity: A systematic review. Curr Drug

Targets. 19:1095–1107. 2018.

|

|

59

|

Ha H, Lee JH, Kim HN and Lee ZH:

α-Tocotrienol inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption by suppressing

RANKL expression and signaling and bone resorbing activity. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 406:546–551. 2011.

|

|

60

|

Ormsby RT, Hosaka K, Evdokiou A, Odysseos

A, Findlay DM, Solomon LB and Atkins GJ: The effects of vitamin E

analogues α-Tocopherol and γ-Tocotrienol on the human osteocyte

response to ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene wear

particles. Prosthesis. 4:480–489. 2022.

|

|

61

|

Kim KW, Kim BM, Won JY, Min HK, Lee SJ,

Lee SH and Kim HR: Tocotrienol regulates osteoclastogenesis in

rheumatoid arthritis. Korean J Intern Med. 36(Suppl 1): S273–S282.

2021.

|

|

62

|

Wong SK, Chin KY and Ima-Nirwana S: The

effects of tocotrienol on bone peptides in a rat model of

osteoporosis induced by metabolic syndrome: The possible

communication between bone cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

16:33132019.

|

|

63

|

Chin KY, Abdul-Majeed S, Fozi NF and

Ima-Nirwana S: Annatto tocotrienol improves indices of bone static

histomorphometry in osteoporosis due to testosterone deficiency in

rats. Nutrients. 6:4974–4983. 2014.

|

|

64

|

Deng L, Ding Y, Peng Y, Wu Y, Fan J, Li W,

Yang R, Yang M and Fu Q: γ-Tocotrienol protects against

ovariectomy-induced bone loss via mevalonate pathway as HMG-CoA

reductase inhibitor. Bone. 67:200–207. 2014.

|

|

65

|

Soelaiman IN, Ming W, Abu Bakar R, Hashnan

NA, Mohd Ali H, Mohamed N, Muhammad N and Shuid AN: Palm

tocotrienol supplementation enhanced bone formation in

oestrogen-deficient rats. Int J Endocrinol. 2012:5328622012.

|

|

66

|

Mohamad NV, Ima-Nirwana S and Chin KY:

Self-emulsified annatto tocotrienol improves bone histomorphometric

parameters in a rat model of oestrogen deficiency through

suppression of skeletal sclerostin level and RANKL/OPG ratio. Int J

Med Sci. 18:3665–3673. 2021.

|

|

67

|