Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most

common cancer and the third leading cause of cancer related

mortality worldwide (1).

Clinically, surgical resection remains the primary mode of therapy

for advanced HCC. In the absence of an effective adjuvant therapy,

liver cancer has a poor prognosis (2). HCC is a highly malignant tumor with a

potent capacity to invade locally and metastasize distantly

(2,3); therefore, an approach that decreases

its ability to invade and metasta-size may facilitate the

development of an effective adjuvant therapy.

Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is a non-receptor

cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase that plays a key role in the regulation

of cell proliferation and migration in both inflammation and

neoplasia (4). FAK appears to be

essential for the regulation of cell migration and invasion

properties (5–7). It is associated with integrin

receptors and integrates with other molecules to form a complex

that transmits signals from the extracellular matrix to the cell

cytoskeleton (8,9). In 2010, the expression and prognostic

significance of FAK were reported in liver cancer and FAK was found

to play an important role in invasion and metastasis of HCC

(10). Therefore, FAK may be a

promising therapeutic target for HCC (11). Our previous studies showed that

prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) induces cell adhesion

and migration by activating FAK in HCC cells (12). However, the specific mechanism of

this activation was not investigated.

PGE2 is one of the predominant metabolic

products of arachidonic acid. In previous studies, PGE2

was found to play a major role in promoting tumor cell growth,

migration and invasion in many cancer types (13–16).

PGE2 has been shown to regulate tumor development and

progression by combining with E prostanoid receptors (EP receptors)

on the surface of the cell membrane and activating their

predominant signal transduction pathways (17).

There are four types of EP receptors expressed on

the membrane surface of HCC cells (1). Among them, the EP1 receptor is

accepted to be involved in cell growth, invasion and metastasis in

many cancers, such as colon cancer (18), skin cancer (19) and cervical cancer (20). Recently, the EP1 receptor was

reported to enhance cell invasion in HCC cells (21), although it is unclear whether FAK

activation is involved. In the present study, PGE2 was

found to upregulate FAK phosphorylation via the EP1 receptor in HCC

cells. Protein kinase C (PKC), c-Src and epidermal growth factor

receptor (EGFR) were all involved in the EP1 receptor-mediated FAK

phosphorylation and cell adhesion and migration. Our data generated

from the present studies may provide significant insights into the

mechanisms of EP1 receptor-mediated FAK activation and ultimately

lead to the development of novel management strategies and

therapeutics for cell invasion and metastasis in hepatocellular

carcinoma.

Materials and methods

Materials

The human HCC cell line Huh-7 and human embryonic

kidney (HEK) 293 cells were obtained from American Type Culture

Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s

medium (DMEM) was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA).

PGE2, 17-phenyl trinor-PGE2

(17-PT-PGE2) and sc-19220 were from Cayman Chemical Co.

(Ann Arbor, MI, USA). AG1478 was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO,

USA). Bisindolymaleimide I (#203290),

phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (#524400) and PP2 (#529573) were

obtained from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Recombinant human

epidermal growth factor (EGF; #AF-100-15) was from PeproTech (Rocky

Hill, NJ, USA). WST reagent from the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

was from Dojindo Laboratories (Kumamoto, Japan). The protein assay

was from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA, USA). Electrochemiluminescence

(ECL) reagents were from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ,

USA). The PKC assay kit was from Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA).

[γ-32P]ATP (#BLU002A) was from Perkin-Elmer (Waltham,

MA, USA). G418 sulfate was from Amresco (Solon, OH, USA). The

following were commerically obtained antibodies: anti-FAK antibody

(sc-558; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA);

anti-phosphorylated FAK Y397 antibody (#611806, BD Biosciences,

Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA); phosphorylated Src antibody (#2101, Cell

Signaling Technology Danvers, MA, USA); total Src antibody (#21168,

SAB, College Park, MD, USA); anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma).

Cell lines and culture

Huh-7 cells and HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM

with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100

μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cell adhesion assays

Cell adhesion assays were performed in 96-well

culture cell plates. Cells (5×104) were added to each

well of the plates and pharmacological agents were added at the

indicated time. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 3 h and then

washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove

unattached cells. The attached cells were stained with WST at 37°C

for 2 h. Adherent cells were quantified by measuring the absorbance

at 450 nm.

Cell migration assays

Cell migration assays were performed in 12-well

transwell units. Before the experiment, the lower surfaces of the

membranes were coated with gelatin (1%) diluted in PBS. Huh-7 cells

(5×104) were added to the upper chamber and 1 ml

complete DMEM to the lower chamber of the transwell.

Pharmacological agents were added at the indicated time. After

incubation at 37°C for 12 h, the cells were fixed with ethanol and

then stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 30 min at room

temperature. After washing the wells with PBS, the cells were

removed from the upper surface of the membrane by wiping with a

moist cotton swab. The cells migrated to the lower surface of the

membrane were solubilized with 300 μl of 10% acetic acid and

quantified by measuring the absorbance at 570 nm.

PKC measurements

Cells were treated with pharmacological agents at

37°C for various times, as indicated in the experiments. The cells

were collected into lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM

NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 100

μg/ml PMSF and aprotinin) and placed on ice for 30 min. Cell

lysates were sonicated on ice for at least 30 sec and then cleared

by centrifugation at 120,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Total protein

(30 μg) (10 μl) for each sample was added to a

microcentrifuge tube and assayed for PKC levels using a direct

human PKC enzyme activity assay kit according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. Briefly, 10 μl of substrate cocktail, PKA

inhibitor cocktail, Assay Dilution Buffer II (ADBII), lipid

activator and diluted [γ-32P]-ATP mixture were added to

a microcentrifuge tube and then the mixture was incubated for 10

min at 30°C with constant agitation. A 25-μl aliquot from

each sample was transferred onto the center of a P81

phosphocellulose paper. The assay squares were washed with 0.75%

phosphoric acid three times, followed by one wash with acetone. The

assay squares were transferred to vials with a scintillation

cocktail and read in a scintillation counter. The counts per minute

(cpm) of the enzyme samples were compared to those of the control

samples containing no enzyme.

Plasmid transfections

The pcDNA3-based plasmid encoding the human EP1

receptor (EP1R-pcDNA3) was a generous gift of Kathy Mccusker in

2007 (Merck Frosst Centre for Therapeutic Research, Canada). HEK293

cells (2×105) were seeded and grown in 6-well culture

plates for 24 h before transfection with the EP1R-pcDNA3 plasmid or

pcDNA3 empty vector control (2 μg) using Lipofectamine

2000TM (5 μl). After incubation for 5 h, the

medium was changed to fresh normal growth DMEM. The efficiency of

transfection was assayed by flow cytometry. The G418 antibiotic was

used to select for HEK293 cells stably expressing the EP1

receptor.

Western blotting

Cells were treated with pharmacological agents at

37°C for various times, as indicated in the experiments. The cells

were collected into lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM

NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 100

μg/ml PMSF and aprotinin) and placed on ice for 30 min. Cell

lysates were sonicated on ice for ≥30 sec and then cleared by

centrifugation at 120,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. Equal amounts of

total proteins (40 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and

transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were

probed with the appropriate antibodies at 4°C overnight with gentle

shaking. The immunoreactivity was detected by ECL and analyzed

using Image lab 4.0 analysis software from Bio-Rad.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. P-values were

calculated using the Student’s t-test for unpaired samples with MS

Excel software. The results were considered significantly different

at P<0.05.

Results

EP1 receptor promotes FAK

phosphorylation, cell adhesion and migration in Huh-7 cells

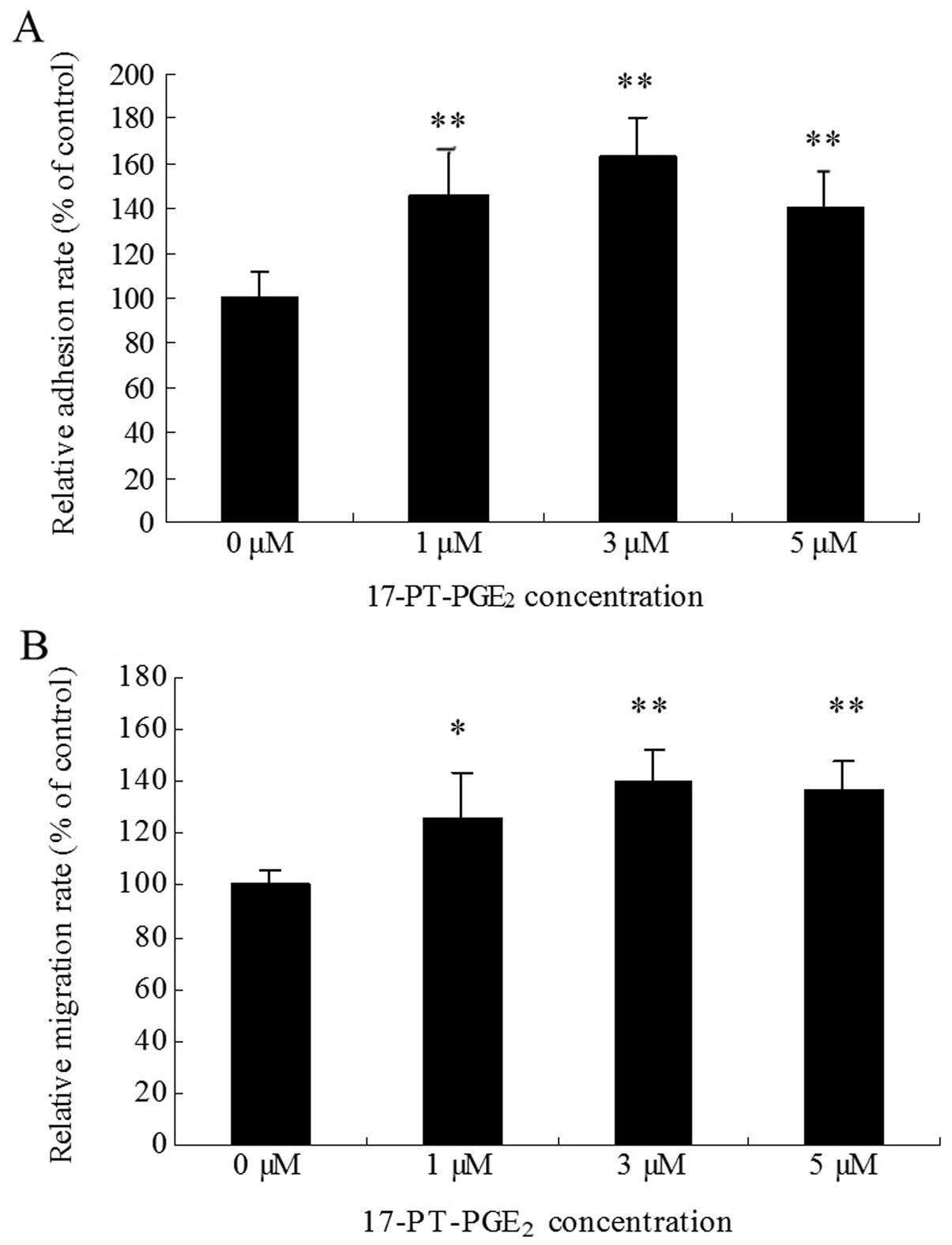

Huh-7 cells were treated with various concentrations

of the EP1 receptor agonist 17-PTPGE2 for 3 h. The WST

assay was used to detect the cell adhesion rate. The results showed

that 17-PT-PGE2 produced a 40–60% increase in cell

adhesion in Huh-7 cells (Fig. 1A).

In the transwell assay, cell migration was found to increase by

20–40% when the cells were treated with 17-PT-PGE2 for

12 h (Fig. 1B). At the

concentration of 3 μM, 17-PT-PGE2 caused maximal

responses both in cell adhesion and migration assays.

We previously found that PGE2 stimulates

cell adhesion and migration in HCC cells by increasing FAK Y397

phosphorylation (12). To

determine whether the EP1 receptor is involved in

PGE2-mediated FAK phosphorylation, Huh-7 cells were

exposed to different concentrations of exogenous

17-PT-PGE2 for different periods of time. As shown in

Fig. 2A, an increase in FAK

phosphorylation at the Y397 site was detected 15 min after

17-PT-PGE2 treatment and the maximal response (∼2-fold

induction) was reached at 30 min post-treatment with 3 μM

17-PT-PGE2 (Fig. 2B).

Based on these findings, treatment with 3 μM

17-PT-PGE2 for 30 min was used for subsequent

experiments in Huh-7 cells. As shown in Fig. 2C, pre-treatment with sc-19220, a

specific antagonist of the EP1 receptor, suppressed

PGE2-mediated upregulation of FAK Y397

phosphorylation.

| Figure 2Effects of EP1 receptor on FAK Y397

phosphorylation in Huh-7 cells. (A) Effects of EP1 agonist on FAK

phosphorylation at Y397 in Huh-7 cells cultured and treated with 3

μM exogenous 17-PT-PGE2 for 0, 15, 30 and 60 min.

(B) Effects of EP1 agonist 17-PT-PGE2 treatment (0, 1, 3

or 5 μM for 30 min) on FAK Y397 phosphorylation in Huh-7

cells. FAK phosphorylation increased after stimulation with

different concentrations of 17-PT-PGE2 and the maximal

response was reached at 30 min post-treatment with 3 μM

17-PT-PGE2. (C) Effects of an EP1 antagonist on

17-PT-PGE2-mediated FAK phosphorylation in Huh-7 cells.

Cells were pre-treated with 10 μM sc-19220 for 30 min,

followed by treatment with 3 μM 17-PT-PGE2 for 30

min. (D) Effects of the EP1 receptor expression on

17-PT-PGE2-mediated FAK phosphorylation in HEK293 cells.

HEK293 cells (3×105 cells) were seeded in 6-well plates

and cultured for 24 h before transfection with 2 μg of the

EP1R-pcDNA3 plasmid or empty pcDNA3 plasmid as a control. After

transfection, cells expressing the EP1 receptor were selected by

300 μg/ml G418. EP1 receptor-transfected HEK293 cells were

exposed to 2 μM PGE2 for 30 min, with or without

sc-19220 pre-treatment. Equal amounts of total proteins were

separated by SDS-PAGE and relative levels of phosphorylated FAK and

total FAK expression were determined using anti-phospho-FAK and

anti-FAK antibodies. β-actin was detected as a loading control.

Densitometric quantitation of the above blots is shown. Results are

presented as means ± SD from three different experiments.

*P<0.05, compared to control cells;

**P<0.01, compared to control cells;

#P<0.05, compared to PGE2-treated

cells. |

To confirm the role of the EP1 receptor in the

induction of FAK phosporylation, HEK293 cells were transfected with

the EP1 receptor expression plasmid (EP1R-pcDNA3) and selected with

G418 to obtain a stable expression cell culture. As illustrated in

Fig. 2D, expression of the EP1

receptor did not alter the basal phosphorylation level of FAK.

However, FAK phosphorylation was significantly upregulated in the

EP1R-transfected cells when treated with PGE2, compared

with control cells. At the same time, pre-treatment with sc-19220

significantly decreased PGE2-mediated FAK Y397

phosphorylation in EP1R-transfected cells.

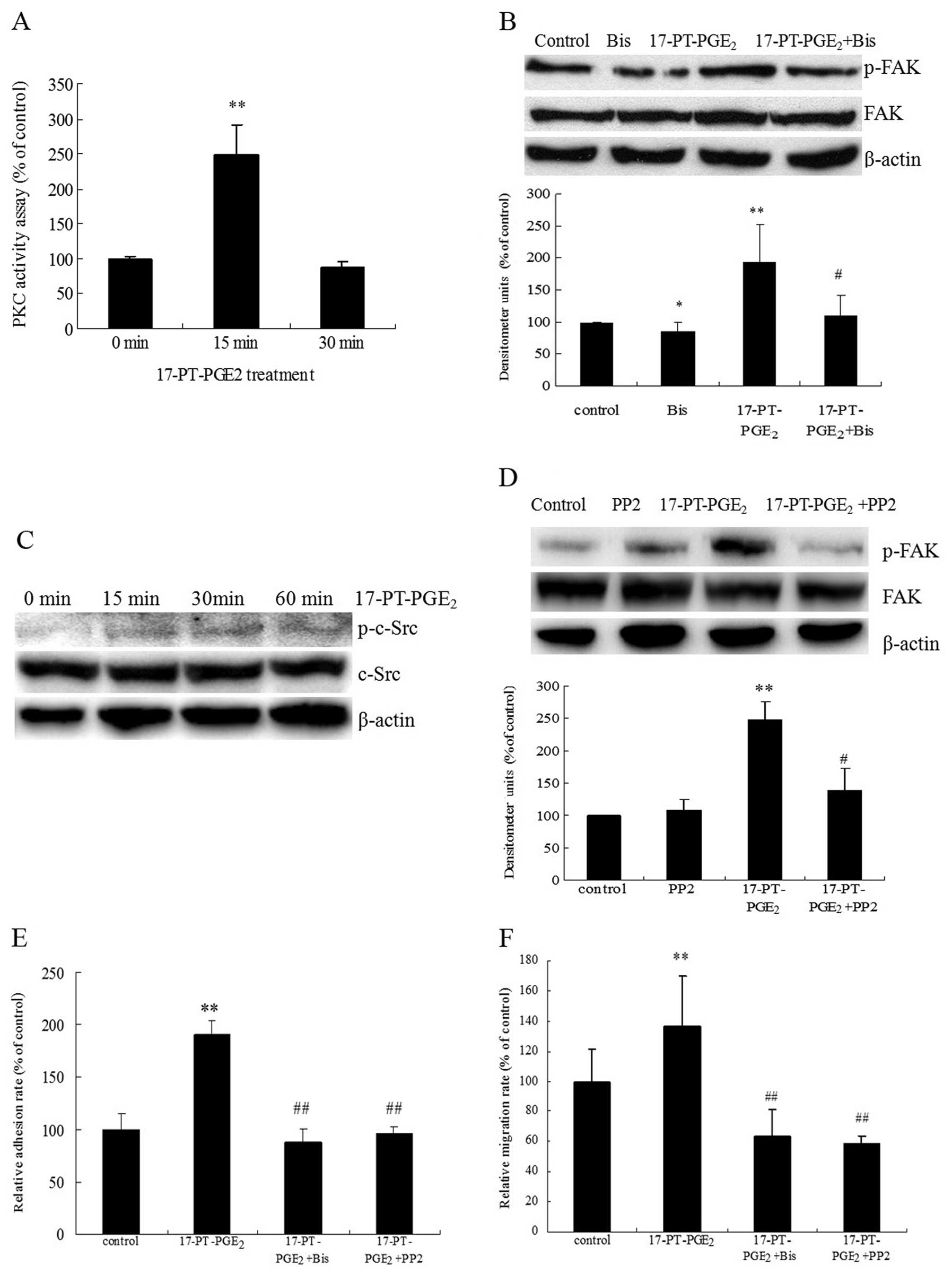

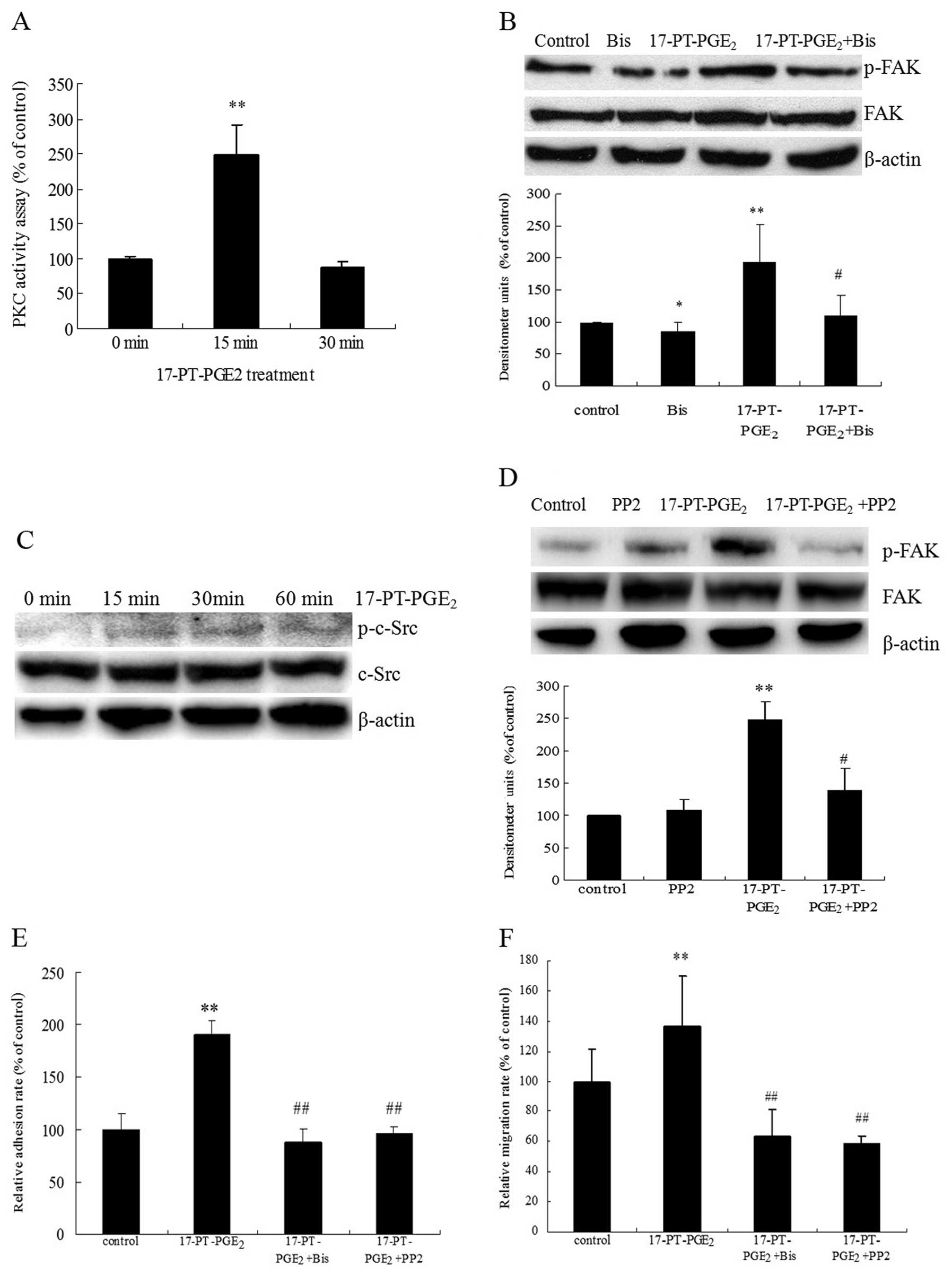

PKC/c-Src signaling is involved in

EP1-mediated FAK phosphorylation, cell adhesion and migration in

Huh-7 cells

The PKC/c-Src pathway is reportedly involved in

EP1-mediated cell migration (22).

Therefore, the relationship between PKC/c-Src activation and FAK

phosphorylation was examined in the present study. PKC activity and

c-Src phosphorylation in response to 17-PT-PGE2 were

directly measured in Huh-7 cells. Treatment of Huh-7 cells with

17-PT-PGE2 upregulated PKC activity >2-fold after 15

min and then decreased after 30 min (Fig. 3A). Pre-treatment of cells with the

PKC inhibitor bisindolymaleimide I (Bis) significantly reduced the

17-PT-PGE2-mediated FAK phosphorylation (Fig. 3B). At the same time,

17-PT-PGE2 induced the phosphorylation of c-Src at Y416,

which could be detected at 15 min after treatment and then

decreased after 60 min (Fig. 3C).

In addition, pre-treatment of cells with a c-Src inhibitor (PP2)

diminished 17-PT-PGE2-increased FAK phosphorylation

significantly (Fig. 3D). In

addition, pre-treatment of Huh-7 cells with Bis and PP2 completely

blocked 17-PT-PGE2-mediated cell adhesion and migration

(Fig. 3E and F).

| Figure 3Roles of PKC and c-Src pathways in

17-PT-PGE2-mediated FAK phosphorylation in Huh-7 cells.

(A) PKC activity assay. Huh-7 cells were treated with 3 μM

17-P-T-PGE2 for 0, 15 or 30 min. Equal amounts of total

proteins (30 μg) were added to microcentrifuge tubes and

assayed for PKC levels using a direct human PKC enzyme activity

assay kit. (B) Effects of PKC inhibitor on

17-PT-PGE2-mediated FAK phosphorylation in Huh-7 cells

treated with 3 μM 17-PT-PGE2 for 30 min, with or

without pre-treatment of 5 μM Bis for 1 h. Equal amounts of

total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Relative levels of

phosphorylated FAK and total FAK expression were determined using

anti-phospho-FAK and anti-FAK antibodies. β-actin was detected as a

loading control. Densitometric quantitation of the above blots is

shown. (C) Effects of 17-PT-PGE2 on c-Src

phosphorylation at Y416 in Huh-7 cells treated with 3 μM

exogenous 17-PT-PGE2 for 0, 15, 30 or 60 min. Equal

amounts of total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. Relative

levels of phosphorylated c-Src and total c-Src expression were

determined using anti-phospho-c-Src and anti-c-Src antibodies.

β-actin was detected as a loading control. These experiments were

performed three times with similar results. (D) Effects of c-Src

inhibitor on 17-PT-PGE2-mediated FAK phosphorylation in

Huh-7 cells treated with 3 μM 17-P-T-PGE2 for 30

min, with or without pre-treatment of 10 μM PP2 for 1 h.

Equal amounts of total proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE.

Relative levels of phosphorylated FAK and total FAK expression were

determined using anti-phospho-FAK and anti-FAK antibodies. β-actin

was detected as a loading control. Densitometric quantitation of

the above blots is shown. (E) Effects of PKC or c-Src inhibitors on

17-PT-PGE2-mediated cell adhesion in Huh-7 cells. The

cell adhesion assay was performed in 96-well plates. Huh-7 cells

were treated with 3 μM 17-P-T-PGE2 for 3 h, with

or without pre-treatment with 5 μM Bis or 10 μM PP2

for 1 h. The attached cells were stained with WST and quantified by

reading absorbance at 450 nm. (F) Effects of PKC or c-Src

inhibitors on 17-PT-PGE2-mediated cell migration in

Huh-7 cells. The cell migration assay was performed in 12-well

transwells. Huh-7 cells were treated with 3 μM

17-PT-PGE2 for 12 h, with or without pre-treatment of 5

μM Bis or 10 μM PP2 for 1 h. Cells on the lower

surface were stained with 0.1% crystal violet, solubilized with

acetic acid solution and quantified by measuring absorbance at 570

nm. Results are presented as means ± SD from three different

experiments. *P<0.05, compared to control cells;

**P<0.01, compared to control cells;

#P<0.05, compared to cells with 17-PT-PGE2

treatment; ##P<0.01, compared to 17-PT-PGE2-treated

cells. |

In order to clarify whether c-Src functions

downstream of the 17-PT-PGE2-induced PKC pathway,

effects of the PKC activator phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA)

and inhibitor Bis on c-Src phosphorylation were examined. PMA

treatment increased c-Src phosphorylation, as well as the FAK

phosphorylation (Fig. 4A), while

Bis significantly suppressed the 17-PT-PGE2-induced

c-Src phosphorylation (Fig.

4B).

EGFR is involved in EP1-mediated FAK

phosphorylation

In our previous studies, we found that the

phosphorylation level of EGFR increases significantly after

17-PT-PGE2 treatment in HCC cells (23). In the present study, FAK Y397

phosphorylation was found to increase after exposure of Huh-7 cells

to exogenous EGF for 30 min (Fig.

5A). In addition, pre-treatment of cells with the EGFR

inhibitor AG1478 significantly suppressed the

17-PT-PGE2-induced FAK phosphorylation (Fig. 5B). As shown in Fig. 5C and D, pre-treatment with AG1478

mildly suppressed the 17-PT-PGE2-mediated cell adhesion

and completely blocked the 17-PT-PGE2-mediated migration

in Huh-7 cells. In order to clarify whether c-Src is involved in

the 17-PT-PGE2-induced EGFR/FAK pathway, the effect of

AG1478 on c-Src phosphorylation was detected, but surprisingly it

had no effect on 17-PT-PGE2-mediated c-Src

phosphorylation (Fig. 5E).

Discussion

Prostaglandin E2 is one of the major

products of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), which has been shown to drive

cancer cell growth and invasion in many cancer cells. Previous

studies have indicated that COX-2 is overexpressed in many cancer

tissues and that the level of PGE2 is increased in COX-2

over-expressing cells (24–26).

Endogenous and exogenous PGE2 induce angiogenesis

(27,28) and promote tumor cell growth,

migration and invasion in colon cancer (13), renal cancer (16) and lung cancer (15). Selective COX-2 inhibitors were

shown to suppress PGE2 production (29,30)

and reduce cell growth, migration and invasion (29–32).

PGE2 exerts its functions through four

subtypes of receptors expressed on the surface of tumor cells: EP1,

EP2, EP3 and EP4 receptors (17).

It is well accepted that the EP1 receptor promotes development and

progression of many cancers (20).

For example, expression of the EP1 receptor is frequently observed

both in the cytoplasm and/or in the nuclear membrane in many cancer

cells (21,33,34).

BK5.EP1 transgenic mice produce more skin tumors than wild-type

(WT) mice (35). Furthermore, the

EP1 receptor level is associated with cell migration or invasion in

colon cancer cells (18),

chondrosarcoma cells (22) and

oral cancer cells (36).

FAK is a non-receptor, cytoplasmic protein tyrosine

kinase that appears to play a central role in integrin-mediated

signal transduction. Overexpression of FAK enhances cell

proliferation (8,37); while FAK depletion impairs cell

adhesion or migration in colon cancer (38), breast cancer cells (7) and melanoma cells (39). Recently, FAK mRNA and protein, as

well as phosphorylated FAK Tyr397, were found to be overexpressed

both in HCC clinical samples and HCC cell lines (10,11).

Increased FAK and phosphorylated FAK Tyr397 expression levels have

been correlated with tumor stage, vascular invasion and

intrahepatic metastasis in HCC (11).

In our previous study, we found that PGE2

improves cell adhesion, migration and invasion in HCC cells. FAK

plays an important role in PGE2-mediated cell adhesion

and migration, as exogenous PGE2 was shown to greatly

increase phosphorylation of FAK at the Y397 site in a

PGE2 concentration-dependent manner. RNA interference

targeting FAK can suppress PGE2-mediated cell adhesion

and migration significantly (12).

In the present study, 17-PT-PGE2 treatment mimicked the

effects of PGE2 and promoted cell adhesion and migration

in HCC cells. Therefore, we hypothesize that PGE2

upregulates FAK phosphorylation via the EP1 receptor in HCC

cells.

Autophosphorylation at Y397 is required for FAK

activation (40). To date, very

little is known about the effects of EP1 receptor on FAK Y397

activation and molecular mechanisms mediating these effects. In our

previous study, FAK phosphorylation and expression were found to be

upregulated by PGE2 in HCC cells (12). In the present study,

17-PT-PGE2 treatment caused upregulation of FAK Y397

phosphorylation in Huh-7 cells. Expression of the EP1 receptor in

HEK293 cells mimicked the effect of 17-PT-PGE2

treatment. In addition, pre-treatment with sc-19220, the specific

antagonist of the EP1 receptor, suppressed PGE2-mediated

upregulation of FAK Y397 phosphorylation. Our data suggest that the

EP1 receptor is involved in PGE2-mediated activation of

FAK. Because FAK is increasingly recognized as a critical factor in

the development of HCC (11), the

present findings suggest that the EP1 receptor may possibly be

explored as a drug target to prevent the phosphorylation of FAK

Y397 in the prevention and treatment of liver cancer.

PKC has been reported to be involved in the EP1

receptor signaling pathway (17).

The PKC family was first identified as intracellular receptors for

the tumor promoting phorbol esters (41). Activation of PKC by calcium ions

and the second messenger diacylglycerol is thought to play a

central role in the induction of cellular responses to a variety of

ligand-receptor systems and in the regulation of cellular

responsiveness to external stimuli (41,42).

PKC was found to be associated with the development of HCC. For

example, mRNA levels of several PKC isoforms were shown to be

significantly increased in HCC samples, as compared to the

corresponding non-cancerous liver tissues. PKCα expression is also

significantly correlated with tumor size and the tumor, node and

metastasis (TNM) stage (43).

Meanwhile, reduction of PKC expression by RNA interference or

selective inhibitors greatly decreases cell proliferation,

migration and invasion in HCC cells (44).

Our data show that PKC activities were enhanced

after 17-PT-PGE2 treatment for 15 min, while the

selective PKC inhibitor, Bis, completely blocked

17-PT-PGE2-mediated cell adhesion and migration. These

results support that PKC is involved in EP1 receptor-mediated cell

adhesion and migration in HCC cells. The involvement of PKC in EP1

receptor-mediated FAK phosphorylation was further confirmed by use

of PMA, a selective PKC activator, which promoted the

phosphorylation of FAK at Y397 in Huh-7 cells. In addition, Bis

pre-treatment diminished the 17-PT-PGE2-mediated FAK

phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation of FAK Y397 was determined to create

a high-affinity binding site for SH2 domains of Src family kinases

to form a FAK/Src complex. A major function of FAK is to recruit

and activate Src at cell-extracellular matrix adhesion sites

(40). However, FAK Y397 is not

strictly an autophosphorylation site and signal amplification can

also result from phosphorylation of this site by Src (45). Therefore, the effect of c-Src on

EP1 receptor-induced FAK Y397 phosphorylation in Huh-7 cells was

further evaluated in this study.

C-Src activity is regulated by tyrosine

phosphorylation at two distinct sites, Y416 and Y527 and the active

state of c-Src is p-Y416-c-Src (46). Our results showed that c-Src Y416

phosphorylation was enhanced after 17-PT-PGE2 treatment

for 15 min. The selective Src inhibitor PP2, caused a significant

reduction in 17-PT-PGE2-mediated FAK Y397

phosphorylation. PP2 pre-treatment completely blocked

17-PT-PGE2-mediated cell adhesion and migration.

Furthermore, PMA treatment increased c-Src phosphorylation, while

Bis partly suppressed the 17-PT-PGE2-induced c-Src

phosphorylation. These data suggest that the PKC/c-Src signal

pathway is involved in EP1 receptor-mediated FAK activation, cell

adhesion and migration in HCC cells.

EGFR has been widely accepted to improve cell growth

and invasion in many cancer cell types (47). Several studies in the last decade

have shown that the EP receptor pathway also modulates activation

of the EGFR (48). In 2006, Han

et al revealed a novel crosstalk between the EP1 and EGFR

signaling pathways that synergistically promote cancer cell growth

and invasion. The association of EP1 with EGFR was found by

immunoprecipitation after HCC cells were treated with

PGE2 or EP1 agonist (21). Of interest, EGFR activation was

found to be sufficient to induce activation of the Src-FAK pathway

in tumor cells (49,50). As the EGFR/Src/FAK pathway has been

implicated in cell growth, migration and invasion in various cancer

cells (49–51), the involvement of this signaling

pathway in EP1 receptor-mediated cell adhesion and migration was

explored in this study.

In our previous study, we found that the

phosphorylation level of EGFR increases significantly after

17-PT-PGE2 treatment in HCC cells (23). In the present study, exogenous EGF

was observed to increase FAK Y397 phosphorylation. The selective

EGFR inhibitor, AG1478, greatly suppressed

17-PT-PGE2-induced FAK Y397 phosphorylation. At the same

time, AG1478 pre-treatment mildly suppressed

17-PT-PGE2-mediated cell adhesion and completely blocked

17-PT-PGE2-mediated cell migration. Surprisingly, AG1478

had no effect on 17-PT-PGE2-mediated c-Src Y416

phosphorylation. Our results suggest that EGFR is also associated

with EP1 receptor-mediated FAK activation, while c-Src may be not

involved in EGFR-induced FAK activation in HCC cells.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the

PGE2 EP1 receptor upregulates FAK phosphorylation at

Y397 to improve cell adhesion and migration. PKC/c-Src and EGFR

signaling pathways are both involved in EP1 receptor-mediated FAK

phosphorylation. The PGE2/EP1/PKC/c-Src and

PGE2/EP1/EGFR signaling pathway may coordinately

regulate FAK activation, cell adhesion and migration in HCC

(Fig. 6). In this regard, our

present findings provide important new information regarding the

putative role of the EP1 receptor in FAK phosphorylation in HCC

cells and suggest that targeting the PGE2/EP1/FAK signal

pathway may provide new therapeutic strategies for both the

prevention and treatment of this malignant disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Kathy Mccusker (Merck Frosst Centre for

Therapeutic Research, Canada) for providing the pcDNA3 plasmid

construct encoding the EP1 receptor. This study was supported in

part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81101496,

81172003), Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher

Education of China (20113234120009) and a Project Funded by the

Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education

Institutions (PAPD).

References

|

1.

|

Wu T: Cyclooxygenase-2 in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 32:28–44. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2.

|

Uchino K, Tateishi R, Shiina S, Kanda M,

Masuzaki R, Kondo Y, Goto T, Omata M, Yoshida H and Koike K:

Hepatocellular carcinoma with extrahepatic metastasis: clinical

features and prognostic factors. Cancer. 117:4475–4483. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Pang RW, Joh JW, Johnson PJ, Monden M,

Pawlik TM and Poon RT: Biology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann

Surg Oncol. 15:962–971. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4.

|

Mon NN, Ito S, Senga T and Hamaguchi M:

FAK signaling in neoplastic disorders: a linkage between

inflammation and cancer. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1086:199–212. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Meng XN, Jin Y, Yu Y, Bai J, Liu GY, Zhu

J, Zhao YZ, Wang Z, Chen F, Lee KY and Fu SB: Characterisation of

fibronectin-mediated FAK signalling pathways in lung cancer cell

migration and invasion. Br J Cancer. 101:327–334. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Kwiatkowska A, Kijewska M, Lipko M, Hibner

U and Kaminska B: Downregulation of Akt and FAK phosphorylation

reduces invasion of glioblastoma cells by impairment of MT1-MMP

shuttling to lamellipodia and downregulates mMPs expression.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1813:655–667. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Chan KT, Cortesio CL and Huttenlocher A:

FAK alters invadopodia and focal adhesion composition and dynamics

to regulate breast cancer invasion. J Cell Biol. 185:357–370. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Guan JL: Integrin signaling through FAK in

the regulation of mammary stem cells and breast cancer. IUBMB Life.

62:268–276. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Mitra SK and Schlaepfer DD:

Integrin-regulated FAK-Src signaling in normal and cancer cells.

Curr Opin Cell Biol. 18:516–523. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Yuan Z, Zheng Q, Fan J, Ai KX, Chen J and

Huang XY: Expression and prognostic significance of focal adhesion

kinase in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

136:1489–1496. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Chen JS, Huang XH, Wang Q, Chen XL, Fu XH,

Tan HX, Zhang LJ, Li W and Bi J: FAK is involved in invasion and

metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis.

27:71–82. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Bai XM, Zhang W, Liu NB, Jiang H, Lou KX,

Peng T, Ma J, Zhang L, Zhang H and Leng J: Focal adhesion kinase:

important to prostaglandin E2-mediated adhesion, migration and

invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 21:129–136.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Xia D, Wang D, Kim SH, Katoh H and DuBois

RN: Prostaglandin E2 promotes intestinal tumor growth via DNA

methylation. Nat Med. 18:224–226. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Harding P and LaPointe MC: Prostaglandin

E2 increases cardiac fibroblast proliferation and increases cyclin

D expression via EP1 receptor. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty

Acids. 84:147–152. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Kim JI, Lakshmikanthan V, Frilot N and

Daaka Y: Prostaglandin E2 promotes lung cancer cell migration via

EP4-betaArrestin1-c-Src signalsome. Mol Cancer Res. 8:569–577.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Wu J, Zhang Y, Frilot N, Kim JI, Kim WJ

and Daaka Y: Prostaglandin E2 regulates renal cell carcinoma

invasion through the EP4 receptor-Rap GTPase signal transduction

pathway. J Biol Chem. 286:33954–33962. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Boie Y, Stocco R, Sawyer N, Slipetz DM,

Ungrin MD, Neuschäfer-Rube F, Püschel GP, Metters KM and Abramovitz

M: Molecular cloning and characterization of the four rat

prostaglandin E2 prostanoid receptor subtypes. Eur J Pharmacol.

340:227–241. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

O’Callaghan G, Kelly J, Shanahan F and

Houston A: Prostaglandin E2 stimulates Fas ligand expression via

the EP1 receptor in colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 99:502–512.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Rundhaug JE, Simper MS, Surh I and Fischer

SM: The role of the EP receptors for prostaglandin E2 in skin and

skin cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 30:465–480. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Liu H, Xiao J, Yang Y, Liu Y, Ma R, Li Y,

Deng F and Zhang Y: COX-2 expression is correlated with VEGF-C,

lymphangiogenesis and lymph node metastasis in human cervical

cancer. Microvasc Res. 82:131–140. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Han C, Michalopoulos GK and Wu T:

Prostaglandin E2 receptor EP1 transactivates EGFR/MET receptor

tyrosine kinases and enhances invasiveness in human hepatocellular

carcinoma cells. J Cell Physiol. 207:261–270. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22.

|

Liu JF, Fong YC, Chang CS, Huang CY, Chen

HT, Yang WH, Hsu CJ, Jeng LB, Chen CY and Tang CH: Cyclooxygenase-2

enhances alpha2beta1 integrin expression and cell migration via EP1

dependent signaling pathway in human chondrosarcoma cells. Mol

Cancer. 9:432010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Bai XM, Jiang H, Ding JX, Peng T, Ma J,

Wang YH, Zhang L, Zhang H and Leng J: Prostaglandin E2 upregulates

survivin expression via the EP1 receptor in hepatocellular

carcinoma cells. Life Sci. 86:214–223. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Leng J, Han C, Demetris AJ, Michalopoulos

GK and Wu T: Cyclooxygenase-2 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma

cell growth through Akt activation: evidence for Akt inhibition in

celecoxib-induced apoptosis. Hepatology. 38:756–768. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Wendum D, Masliah J, Trugnan G and Fléjou

JF: Cyclooxygenase-2 and its role in colorectal cancer development.

Virchows Arch. 445:327–333. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Zha S, Yegnasubramanian V, Nelson WG,

Isaacs WB and De Marzo AM: Cyclooxygenases in cancer: progress and

perspective. Cancer Lett. 215:1–20. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Alfranca A, López-Oliva JM, Genís L,

López-Maderuelo D, Mirones I, Salvado D, Quesada AJ, Arroyo AG and

Redondo JM: PGE2 induces angiogenesis via MT1-MMP-mediated

activation of the TGFbeta/Alk5 signaling pathway. Blood.

112:1120–1128. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28.

|

Zhang Y and Daaka Y: PGE2 promotes

angiogenesis through EP4 and PKA Cγ pathway. Blood. 118:5355–5364.

2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29.

|

Cui W, Yu CH and Hu KQ: In vitro and in

vivo effects and mechanisms of celecoxib-induced growth inhibition

of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Clin Cancer Res.

11:8213–8221. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30.

|

Wu T, Leng J, Han C and Demetris AJ: The

cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib blocks phosphorylation of Akt

and induces apoptosis in human cholangiocarcinoma cells. Mol Cancer

Ther. 3:299–307. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31.

|

Boonmasawai S, Akarasereenont P,

Techatraisak K, Thaworn A, Chotewuttakorn S and Palo T: Effects of

selective COX-inhibitors and classical NSAIDs on endothelial cell

proliferation and migration induced by human cholangiocarcinoma

cell culture. J Med Assoc Thai. 92:1508–1515. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32.

|

Tsai WC, Hsu CC, Chou SW, Chung CY, Chen J

and Pang JH: Effects of celecoxib on migration, proliferation and

collagen expression of tendon cells. Connect Tissue Res. 48:46–51.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33.

|

Thorat MA, Morimiya A, Mehrotra S, Konger

R and Badve SS: Prostanoid receptor EP1 expression in breast

cancer. Mod Pathol. 21:15–21. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34.

|

Han C and Wu T: Cyclooxygenase-2-derived

prostaglandin E2 promotes human cholangiocarcinoma cell growth and

invasion through EP1 receptor-mediated activation of the epidermal

growth factor receptor and Akt. J Biol Chem. 280:24053–24063. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35.

|

Surh I, Rundhaug JE, Pavone A, Mikulec C,

Abel E, Simper M and Fischer SM: The EP1 receptor for prostaglandin

E2 promotes the development and progression of malignant murine

skin tumors. Mol Carcinog. 51:553–564. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36.

|

Yang SF, Chen MK, Hsieh YS, Chung TT,

Hsieh YH, Lin CW, Su JL, Tsai MH and Tang CH: Prostaglandin E2/EP1

signaling pathway enhances intercellular adhesion molecule 1

(ICAM-1) expression and cell motility in oral cancer cells. J Biol

Chem. 285:29808–29816. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37.

|

Yamamoto D, Sonoda Y, Hasegawa M,

Funakoshi-Tago M, Aizu-Yokota E and Kasahara T: FAK overexpression

upregulates cyclin D3 and enhances cell proliferation via the PKC

and PI3-kinase-Akt pathways. Cell Signal. 15:575–583. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38.

|

von Sengbusch A, Gassmann P, Fisch KM,

Enns A, Nicolson GL and Haier J: Focal adhesion kinase regulates

metastatic adhesion of carcinoma cells within liver sinusoids. Am J

Pathol. 166:585–596. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39.

|

Hess AR and Hendrix MJ: Focal adhesion

kinase signaling and the aggressive melanoma phenotype. Cell Cycle.

5:478–480. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40.

|

Cox BD, Natarajan M, Stettner MR and

Gladson CL: New concepts regarding focal adhesion kinase promotion

of cell migration and proliferation. J Cell Biochem. 99:36–52.

2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41.

|

Bosco R, Melloni E, Celeghini C, Rimondi

E, Vaccarezza M and Zauli G: Fine tuning of protein kinase C (PKC)

isoforms in cancer: shortening the distance from the laboratory to

the bedside. Mini Rev Med Chem. 11:185–199. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42.

|

Rosse C, Linch M, Kermorgant S, Cameron

AJ, Boeckeler K and Parker PJ: PKC and the control of localized

signal dynamics. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 11:103–112. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43.

|

Wu TT, Hsieh YH, Wu CC, Hsieh YS, Huang CY

and Liu JY: Overexpression of protein kinase C alpha mRNA in human

hepatocellular carcinoma: a potential marker of disease prognosis.

Clin Chim Acta. 382:54–58. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44.

|

Wu TT, Hsieh YH, Hsieh YS and Liu JY:

Reduction of PKC alpha decreases cell proliferation, migration, and

invasion of human malignant hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cell

Biochem. 103:9–20. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45.

|

Siesser PM and Hanks SK: The signaling and

biological implications of FAK overexpression in cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 12:3233–3237. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46.

|

Lau GM, Lau GM, Yu GL, Gelman IH, Gutowski

A, Hangauer D and Fang JW: Expression of Src and FAK in

hepatocellular carcinoma and the effect of Src inhibitors on

hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro. Dig Dis Sci. 54:1465–1474. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47.

|

Fischer OM, Hart S, Gschwind A and Ullrich

A: EGFR signal transactivation in cancer cells. Biochem Soc Trans.

31:1203–1208. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48.

|

Buchanan FG, Wang D, Bargiacchi F and

DuBois RN: Prostaglandin E2 regulates cell migration via the

intracellular activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J

Biol Chem. 278:35451–35457. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49.

|

Wang SE, Xiang B, Zent R, Quaranta V,

Pozzi A and Arteaga CL: Transforming growth factor β induces

clustering of HER2 and integrins by activating Src-FAK and receptor

association to the cytoskeleton. Cancer Res. 69:475–482. 2009.

|

|

50.

|

Aponte M, Jiang W, Lakkis M, Li MJ,

Edwards D, Albitar L, Vitonis A, Mok SC, Cramer DW and Ye B:

Activation of PAF-receptor and pleiotropic effects on tyrosine

phospho-EGFR/Src/FAK/Paxillin in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res.

68:5839–5848. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51.

|

Calandrella SO, Barrett KE and Keely SJ:

Transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor mediates

muscarinic stimulation of focal adhesion kinase in intestinal

epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol. 203:103–110. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|