Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is a significant health problem

worldwide, and is the second most common cause of cancer-associated

mortality (1). It is well known

that GC results from combination of a complex series of genetic and

epigenetic events. It is reported that epigenetic alteration

contributes to the progression of GC via regulating the expression

of tumor suppressor genes (TSGs). The silencing of TSGs by these

epigenetic regulators is recognized as a vital mechanism in GC

formation (2–4). Therefore, a better understanding of

the abnormal epigenetic modification of GC is key for determining

how to inhibit GC progression effectively.

DNA methylation and histone modifications are key

players in epigenetic modification, and appear to be linked to each

other (5,6). Early studies have shown that DNA

methyl-transferases (DNMTs), together with the methyl-CpG-binding

protein MECP2, localize to DNA-methylated promoters and recruit a

protein complex that contains histone deacetylases (HDACs) and

histone methyltransferases (7–9).

Extinction of DNA methylation affecting H3 methylation and other

histone modifications have also been found in Arabidopsis

and human cells (10,11). These studies suggest DNA

methylation induces chromatin structural changes through alteration

of histone modifications. DNA methylation and histone modifications

likely have a mutually reinforcing relationship and both are

required for stable and long-term epigenetic silencing of TSGs.

Aberrant DNA methylation and histone modifications lead to

downregulation or silencing of TSGs and are often found in CpG-rich

sites, known as CpG islands, located in the promoter region of many

TSGs (12–14). The 5′-end of the PSD gene contains

five CpG islands, suggesting that its expression may be controlled

by epigenetic modification.

In our previous studies (15,16),

genome-wide analysis of histone modifications, using a chromatin

immunoprecipitation microarray (ChIP-chip) investigated inactive

genes in GC, with the aim of identifying targets of genes

controlled by histone modifications. We identified the PSD gene as

a possible TSG in GC. PSD is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor

for ADP-ribosylation factor 6 (15), which regulates the membrane

trafficking of small G proteins (16). It is located on human chromosome

10q24 and encodes a 71-kDa protein (17). Okada et al (18) reported that DNA methylation at the

PSD promoter is more frequently methylated in ulcerative colitis

(UC)-associated colorectal cancer tissues compared to

non-neoplastic UC epithelia. In addition, PSD mRNA is positively

correlated with the methylation status of PSD, however, little is

known about the association between epigenetic alteration and PSD

expression in GC.

In the present study, we investigated PSD expression

in GC cells and tissues, and aimed to verify whether decreased PSD

expression in GC is related to DNA methylation and repressive

histone modification at the PSD promoter. Four GC cell lines and

one normal gastric cell line were used to examine PSD mRNA

expression and epigenetic alteration. In addition, 40 GC tissue

specimens and 40 corresponding non-malignant gastric tissues were

used to observe the mRNA and protein expression of PSD, and its

clinical significance. Suppression of PSD in SGC7901 cells by siRNA

transfection was utilized to detect the function of PSD in GC

progression.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and treatment with

epigenetic agents

GES1, an immortalized normal gastric cell line, was

obtained from the Oncology Institute of China Medical University

(Shenyang, China). Four human GC cell lines, HGC27, AGS, BGC823 and

SGC7901 were obtained from the Institute of Biochemistry and Cell

Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). These cells

were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY,

USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and incubated

at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Four GC lines

were incubated in culture medium with 5 μM DNMT inhibitor

5-aza-2′-de-oxycytidine (DAC; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 3

days, and 0.3 μM of the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin

A (TSA; Sigma) for 1 day. The time, dose and sequence of DAC and/or

TSA were based on previous studies (19,20).

Tissue samples

Human GC samples were collected from 40 patients who

underwent gastrectomy at Cancer Institute of China Medical

University (Shenyang, China) between January 2009 and June 2011.

All GC cases were pathologically confirmed. Non-malignant gastric

tissues that were ≥5 cm away from the tumor were obtained from the

patients. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board

of China Medical University.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

assay

Five million cells were crosslinked with 1%

formaldehyde for 10 min at 37°C, and then 0.125 M glycine was added

to stop the cross-linking. After washing with ice-cold PBS, the

cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer, and sonicated to

generate 200–1,000-bp DNA fragments. The lysate was then divided

into three fractions. The first lysate was precipitated using

antibodies against Lys-9 trimethylated histone H3 (05-1242;

Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), Lys-9 acetylated histone H3

(07-352; Millipore) or Lys-4 trimethylated histone H3 (07-472;

Millipore) at 4°C overnight. The second lysate was incubated with

normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA)

as a negative control. The third lysate was used as an input

control. We added protein G-Sepharose beads to collect the

immunoprecipitated complexes and left them to incubate for 1 h at

4°C. After washing, the beads were treated with RNase (50 mg/ml)

for 30 min at 37°C and then proteinase K overnight. The crosslinks

were then reversed by heating the sample at 65°C for 6 h. DNA was

extracted by the phenol/chloroform method, ethanol precipitated,

and resuspended in 20 μl water.

PCR analysis of immunoprecipitated

DNA

A total of 2 μl of immunoprecipitated DNA, DNA input

control and negative control were used for PCR. The following

primer set for PCR were designed to amplify the overlapping

fragments of 190 bp along the PSD promoter: sense: 5′-gactggctt

ctgtc-gtcctc-3′ and antisense: 5′-ggcagacagtaagagcctgg-3′. PCR

products were subjected to 2.5% agarose gel electrophoresis at 120

V for 40 min and quantified using the Fluor Chen 2.0 system

(Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). For quantitation, PCR amplification

was performed on an ABI 7700 real-time PCR (Applied Biosystems,

Foster City, CA, USA). PCR conditions included an initial

denaturation step of 4 min at 95°C, followed by 35 cycles of 5 sec

at 95°C, 30 sec at 60°C and 20 sec at 72°C. Quantitative ChIP-PCR

values were normalized against values from a standard curve

constructed using input DNA that was extracted for the ChIP

experiment. The ChIP real-time PCR experiments were repeated three

times.

RNA extraction and real-time reverse

transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells and tissues with

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and concentration of RNA were

measured by ultraviolet absorbance at 260 and 280 nm

(A260/A280 ratio) and checked by agarose gel

electrophoresis individually. Total RNA was reverse transcribed

into cDNA using an Expand Reverse Transcriptase kit (Takara,

Dalian, China). Expression of PSD mRNA was detected using real-time

PCR with the following program: 95°C for 30 sec and 35 cycles of

95°C for 5 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The reaction mixture contained

12.5 μl SYBR Green (Takara), 1 μl each primer, 2 μl cDNA, and 8.5

μl diethylpyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water. Primers used were

5′-CTGGGCAAGAACAATGACTTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-GAGGACAGGGCTTCAGGATT-3′

(antisense) for PSD; and 5′-CATGAGAAGTATGACAACAGCCT-3′ (sense) and

5′-AGTCCTTCCACGATACCAAAGT-3′ (antisense) for

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GADPH). The negative

control used DEPC-treated water to replace cDNA templates for every

PCR. The PSD level was expressed as Ct after normalization to the

levels of GAPDH mRNA. The experiment was done in triplicate.

PSD gene knockdown by siRNA

Three pairs of the PSD siRNA sequence were designed

and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). As a result of

relative effectiveness and stability, the following siRNA sequence

was selected in our experiments: 5′-CCAAGCUCAGGGUGUUUTT-3′, 5′-AAA

CACCCUGAGAGCUUGGTT-3′; it was transfected into SGC7901 cells. A

non-silencing siRNA sequence was used as a negative control

(5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′, 5′-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3′). siRNA

transfections were performed according to the manufacturer’s

instructions. SGC7901 cells were seeded in 6-well plates in medium

containing 10% serum 24 h before the experiment. PSD or negative

control siRNA of 100 pmol was diluted in 250 μl Opti-MEM I medium.

Diluted siRNA was mixed with diluted Lipofectamine 2000 for 20 min.

The oligomer-Lipofectamine complexes were applied to the SGC7901

cells. Following transfection, the PSD mRNA levels were assessed 48

h later.

Methylation-specific PCR (MSP)

Genomic DNA was extracted from cells and tissues

with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and collected by ethanol

precipitation. The bisulfite treatment was performed using the EZ

DNA Methylation-Gold kit (Zymo Research, Los Angeles, CA, USA)

according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The CpG map of the PSD

promoter and the location of primers used in this study were

analyzed by http://www.urogene.org/methprimer/index1.html

(21). We found five CpG islands

in the PSD promoter region. The primers for the methylated PSD CpG

island were 5′-GTTG TAGGGAAGCGGTTC-3′ (sense) and 5′-CGACCACGAAA

AAAAACC-3′ (antisense). The primers for the unmethylated PSD CpG

islands were 5′-AGGGTTGTAGGGAAGTGG TTT-3′ (sense) and

5′-CAACCACAAAAAAAAACCTA-3′ (antisense). Peripheral blood cell DNA

from healthy adults treated with SssI methyltransferase (New

England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) and untreated DNA were used as

positive and negative controls, respectively. PCR products were

separated by electrophoresis on 2% agarose gels.

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from cells and tissues

in a lysate buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5%

Nonidet P40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate and phenylmethylsulfonyl

fluoride (all from Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Shanghai,

China). Each sample (60 μg) was electrophoresed in 10%

polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride

membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). After blocking with 5% BSA

in Tris-buffered saline-Tween-20 (20 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM NaCl,

0.05% Tween-20) for 2 h at room temperature and then incubated with

primary antibodies for PSD (1:500 dilution; Novus International,

Littleton, MA, USA), caspase-3 (1:500 dilution; Millipore),

caspase-7 (1:500 dilution; Millipore) or β-actin (1:2,000 dilution;

ZSGB-Bio, Beijing, China) overnight at 4°C. The next day, after

incubation with a 1:2,000 dilution of secondary antibodies at 37°C

for 2 h, and after washing, the immunoreactive protein bands were

visualized using an electrochemiluminescence (ECL) detection kit

(Thermol Biotech, Rockford, IL, USA). The ratio between the optical

density of the protein of interest and β-actin was calculated as

the relative content of the protein detected. Each experiment was

repeated three times.

Wound healing assay

Cells were plated in 6-well plates and maintained in

RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum. A wound was

created in the center of the cell monolayer by a sterile plastic

pipette tip. The cells were allowed to migrate for 24 h. Images

were taken at 0, 12 and 24 h after wounding to assess the ability

of the cells to migrate into the wound area using an inverted

microscope (IX-71; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Matrigel invasion assay

Approximately 5×104 cells cultured in 200

μl serum-free RPMI-1640 medium were seeded onto Matrigel-coated

8-μm pore size Transwell filters (Corning Life Sciences, Corning,

NY, USA) in the upper chambers. Five hundred microliters of

RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum was added to the lower

chambers as a chemoattractant. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a

humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere for 24 h. Cells that had

successfully invaded through the inserts were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde for 30 min, and stained with methylrosanilinium

chloride. The invading cells were counted from five preselected

microscopic fields of view at ×200 magnification. The assay was

performed from three independent experiments.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Cell proliferation was evaluated by CCK-8 assay

(Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Cells were seeded in 96-well

plates (3×103 per well). CCK-8 solution (10/100 μl

medium) was added to each well, and cells were incubated for 1 h at

37°C. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using Synergy2 Multi-Mode

Microplate Reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA). The assay was

conducted in five replicate wells for each sample and three

parallel experiments were performed.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

version 17.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). We used the χ2

test and Fisher’s exact-test to analyze the correlations between

PSD expression and clinicopathological characteristics. Student’s

t-test or one-way ANOVA were used for continuous variables. Data

are expressed as mean ± SD. A value of p<0.05 was considered

statistically significant.

Results

PSD expression is downregulated in GC

cells and tissues

Using real-time RT-PCR to assess mRNA expression of

PSD, we found that PSD was downregulated in HGC27 (0.3651±0.020),

AGS (0.4198±0.053), BGC823 (0.467±0.077) and SGC7901 (0.8188±0.009)

cells compared to the normal mucosal line, GES1 (1-fold as the

control) (p<0.05; Fig. 1A and

B). We also analyzed PSD mRNA expression in 40 paired GC

specimens and corresponding normal tissues. PSD mRNA expression was

significantly lower in GC tissues than in their corresponding

normal tissues (0.3406±0.017 vs. 0.5115±0.018), (p<0.01,

Fig. 1C and D). Western blotting

showed that protein expression of PSD in GC tissues was also lower

than in their corresponding non-tumor tissues (0.2970±0.01706 vs.

0.5523±0.02593), (p<0.01, Fig.

2).

Clinical significance of PSD protein

expression in GC tissues

We further investigated the relationship between PSD

expression and clinicopathological factors. PSD mRNA and PSD

protein levels were both related to tumor differentiation and lymph

node metastasis (Tables I and

II). There was no correlation

with any of the clinicopathological features, including age, sex,

tumor size, invasion depth and TNM stage.

| Table ICorrelation of PSD mRNA expression and

clinicopathological parameters of gastric cancer samples. |

Table I

Correlation of PSD mRNA expression and

clinicopathological parameters of gastric cancer samples.

| | PSD mRNA

expression | |

|---|

| |

| |

|---|

| Variable | Patients (n),

N=40 | Low (%) | High (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | | | | |

| <65 | 18 | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | 0.289 |

| ≥65 | 22 | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | |

| Gender | | | | |

| Male | 21 | 17 (81.0) | 4 (19.0) | 0.724 |

| Female | 19 | 15 (78.9) | 4 (21.1) | |

| Tumor location | | | | |

| Upper + middle | 15 | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | 0.058 |

| Lower | 25 | 21 (84.0) | 4 (16.0) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | | | | |

| <3 | 22 | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | 0.289 |

| ≥3 | 18 | 15 (83.3) | 3 (16.7) | |

| Depth of

invasion | | | | |

| T1+T2 | 17 | 14 (82.4) | 3 (17.6) | 0.480 |

| T3+T4 | 23 | 18 (78.3) | 5 (21.7) | |

| Differentiation | | | | |

| Well/moderate | 18 | 13 (72.2) | 5 (27.8) | 0.015a |

| Poor | 22 | 19 (86.4) | 3 (13.6) | |

| TNM stage | | | | |

| I+II | 15 | 12 (80.0) | 3 (20.0) | 1.000 |

| III+IV | 25 | 20 (80.0) | 5 (20.0) | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | | |

| No | 18 | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | 0.000a |

| Yes | 22 | 20 (90.9) | 2 (9.1) | |

| Table IICorrelation of PSD protein expression

and clinicopathological parameters of gastric cancer samples. |

Table II

Correlation of PSD protein expression

and clinicopathological parameters of gastric cancer samples.

| | PSD protein

expression | |

|---|

| |

| |

|---|

| Variable | Patients (n),

N=40 | Low (%) | High (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | | | | |

| <65 | 18 | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) | 0.665 |

| ≥65 | 22 | 14 (63.6) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Gender | | | | |

| Male | 21 | 15 (71.4) | 6 (28.6) | 0.645 |

| Female | 19 | 13 (68.4) | 6 (31.6) | |

| Tumor location | | | | |

| Upper +

middle | 15 | 11 (73.3) | 4 (26.7) | 0.880 |

| Lower | 25 | 17 (68.0) | 8 (32.0) | |

| Tumor size

(cm) | | | | |

| <3 | 22 | 16 (72.7) | 6 (27.3) | 0.874 |

| ≥3 | 18 | 12 (66.7) | 6 (33.3) | |

| Depth of

invasion | | | | |

| T1+T2 | 17 | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | 0.635 |

| T3+T4 | 23 | 17 (73.9) | 6 (26.1) | |

|

Differentiation | | | | |

| Well/moderate | 18 | 11 (61.1) | 7 (38.9) | 0.014a |

| Poor | 22 | 17 (77.3) | 5 (22.7) | |

| TNM stage | | | | |

| I+II | 15 | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) | 0.443 |

| III+IV | 25 | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | | | |

| No | 18 | 10 (55.6) | 8 (44.4) | 0.000a |

| Yes | 22 | 18 (81.8) | 4 (18.2) | |

Abnormal histone modification is

associated with PSD gene silencing in GC cell lines

To elucidate whether the aberrant DNA methylation

and histone modification of PSD were associated with loss of PSD,

we treated GC cell lines HGC27, AGS, BCG823 and SGC7901 with

epigenetic agents (DAC and TSA). DAC and TSA had different effects

on PSD expression in the PSD-positive cell line (SGC7901) and

PSD-negative cell lines (HGC27, AGS and BCG823). After treatment

with DAC or TSA alone, the PSD mRNA was induced in HGC27, AGS and

BCG823 cells. Combined treatment with both agents restored PSD

expression to a significantly greater degree than did treatment

with either agent alone. In SGC7901 cells, treatment with DAC and

TSA, alone or in combination, had no significant effect on the

restoration of PSD expression (Fig.

3).

To probe the role of histone modifications in the

regulation of the PSD gene expression, we examined the histone

markers H3-K9 trimethylation, H3-K9 acetylation and H3-K4

trimeth-ylation with the PSD promoter region using ChIP. As shown

in Fig. 4, in SGC7901 cells, where

PSD was expressed, the level of H3-K9 trimethylation in the

promoter regions was minimal. In comparison, H3-K9 trimethylation

levels in the PSD gene promoter were high in HGC27, AGS and BCG823

cells. We found that the levels of both H3-K9 acetylation and H3-K4

trimethylation at PSD promoter regions were minimal in HGC27, AGS

and BCG823 cell lines. However, these levels were higher in SGC7901

cells. After treatment with DAC, H3-K9 trimethylation in the PSD

promoter was decreased significantly and H3-K4 trimethylation was

increased significantly in HGC27, AGS and BGC823 cells. We also

found that TSA increased H3-K9 acetylation in the PSD promoter, but

had no effect on H3-K9 trimethylation and H3-K4 trimethylation in

HGC27, AGS and BGC823 cells. Combined treatment significantly

decreased H3-K9 trimethylation, and increased H3-K9 acetylation and

H3-K4 trimethylation in the PSD promoter in PSD-negative cell

lines. The efficiency of combined treatment was similar to DAC or

TSA alone. In the PSD-positive cell line (SGC7901), treatment with

DAC, TSA or both had no significant effect on the histone markers

H3-K9 trimethylation, H3-K9 acetylation and H3-K4

trimethylation.

PSD gene silencing by DNA methylation in

GC cell lines and primary GC

The PSD promoters contain five CpG islands, so we

can suppose that low PSD expression is due to DNA methylation. In

order to test this hypothesis, we first examined the DNA

methylation of PSD in GC cell lines using MSP. We observed

hypermethylation of PSD in HGC27 and AGS cells, partial methylation

in BGC823, and no methylation in SGC7901 cells (Fig. 5). In PSD-negative cell lines

(HGC27, AGS and BGC823), treatment with DAC resulted in DNA

demethylation. TSA had no effect on DNA methylation of PSD, and

combined treatment had no additional effect on DNA demethylation

beyond that produced by treatment with DAC alone. In unmethylated

SGC7901 cells, treatment with DAC, TSA or both did not have a

significant effect on DNA methylation. MSP was performed to detect

methylation status of PSD gene in 40 paired tumor and corresponding

non-malignant gastric tissues. DNA methylation in gastric tissues,

which included methylated and partially methylated tissues,

occurred in 60% (24/40) of primary GC tissues and 27.5% (11/40) of

non-malignant gastric tissues. No methylation was observed in 16

(40%) primary GC tissues and 29 (72.5%) non-malignant gastric

tissues. The difference in methylation status of PSD between

primary GC and non-malignant gastric tissue specimens was

significant (p<0.01, Table

III).

| Table IIIMethylation status of PSD between

gastric tissues (T) and non-malignant gastric tissues (N). |

Table III

Methylation status of PSD between

gastric tissues (T) and non-malignant gastric tissues (N).

| Group | Case | Methylation

(%) | No methylation

(%) | P-value |

|---|

| T | 40 | 24 (60.00) | 16 (40.00) | <0.01a |

| N | 40 | 11 (27.50) | 29 (72.50) | |

Suppression of PSD expression improved

migration and invasion of SGC7901 cells in vitro

To explore further the tumor-suppressive function of

PSD, we used PSD-specific siRNA to knock down PSD expression in the

SGC7901 cell line, in which the level of PSD was relatively high.

RT-PCR confirmed that PSD was downregulated after 48-h transfection

(Fig. 6A). Wound-healing assay

showed that in SGC7901 cells, knockdown of PSD led to cell

migration at 24 h after establishing the wound (Fig. 6B). We also examined whether cell

invasive capacity was altered in PSD-depleted cells. Matrigel

invasion assay showed that SGC7901 cells transfected with PSD siRNA

had more invasion (187.5±4.518) than cells transfected with control

siRNA (66.5±1.848) or untreated SGC7901 cells (64.2±1.250)

(p<0.01, Fig. 6C).

Depletion of PSD reduces apoptosis of

SGC7901 cells

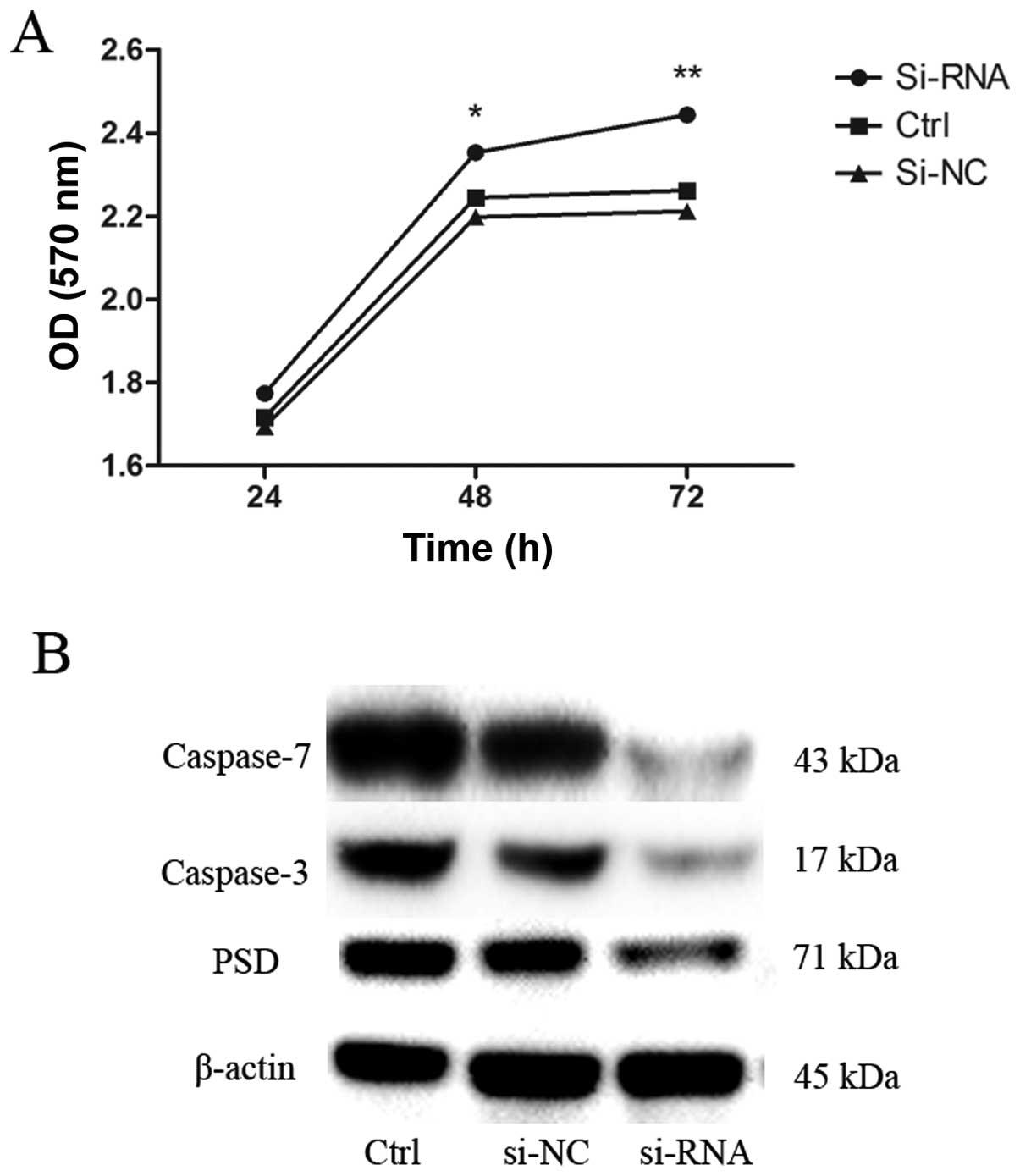

To evaluate the potential effects of transfection

with PSD siRNA on growth of SGC7901 cells, we examined the growth

curve by CCK-8 assay. Depletion of PSD promoted growth of SGC7901

cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig.

7A). We then sought to determine the possible mechanisms that

underlie the depletion of PSD-promoted growth of SGC7901 cells.

Levels of apoptosis-related proteins (caspase-3 and -7) were

evaluated using western blot analysis. Caspase-3 and -7 protein

levels decreased after 48 h of transfection with PSD siRNA

(Fig. 7B).

Discussion

We found that PSD expression was significantly

reduced in GC cell lines and tissues compared to GES1 and normal

tissues. PSD mRNA expression in GC tissues was related to tumor

differentiation and lymph node metastasis. This is in agreement

with the result that differential PSD expression in the GC cell

lines may be related to cell differentiation. PSD mRNA expression

in human poorly differentiated gastric carcinoma cell line HGC27

was lower than in human moderately differentiated gastric carcinoma

cell line SGC7901. This suggests that the degree of malignancy of

GC may be higher when the expression of PSD is low.

We also identified three mechanisms underlying the

decreased expression of PSD: DNA hypermethylation of PSD promoter,

hypertrimethylation of histones H3-K9, and hypotrimethylation of

histones H3-K4 attached to the promoter. First, using ChIP

techniques in four GC cell lines and GES-1 cell line, we showed

that the level of H3-K9 trimethylation in the promoter regions of

PSD-negative cell lines (HGC27, AGS and BCG823) was higher than in

GES-1 and PSD-positive cell line SGC7901. In contrast, the level of

H3-K9 acetylation and H3-K4 trimethylation in the PSD promoter

region was lower than in GES-1 and PSD-positive cell line SGC7901.

Second, we examined the DNA methylation of PSD in GC cell lines and

tissues by MSP. The level of DNA methylation in the promoter

regions of PSD-negative cell lines (HGC27, AGS and BCG823) was

higher than in PSD-positive cell line SGC7901. Lastly, we treated

the GC cell lines with DAC and TSA and found that DAC or combined

treatment restored PSD expression to a significantly greater degree

by means of reversing the level of H3-K9 trimethylation, H3-K4

trimethylation and DNA hypermethylation. TSA significantly

increased H3-K9 acetylation but the effect on restored PSD

expression was limited. Thus, we have reason to believe that

silencing of PSD genes is mainly due to H3-K9 trimethylation, H3-K4

trimethylation and DNA hypermethylation but not H3-K9 acetylation.

Our results are consistent with a model in which H3-K9 methylation

and DNA methylation closely collaborate in maintaining the

repressive state of tumor TSGs. H3-K4 trimethylation is associated

with an open chromatin configuration and activation of TSG

transcription. H3-K4 trimethylation in promoter regions of PSD was

inversely correlated with DNA methylation status (22–24).

To investigate further the tumor-suppressive

functions of PSD, SGC7901 cells were treated with PSD-specific

siRNA to knock down PSD expression. Cell migration and invasion

were markedly enhanced when PSD was silenced. These results are in

agreement with our present study that the expression of PSD was

statistically significantly inverse correlated with lymph node

metastasis. This provides further evidence that PSD may function as

a tumor suppressorin gastric cancer.

We also appraised the effect of PSD-specific siRNA

on SGC7901 cell growth, which indicated that depletion of PSD

promoted growth of SGC7901 cells. Next, we assessed the levels of

apoptosis-related proteins caspase-3 and -7, and found that they

decreased after 48-h transfection with PSD siRNA. These findings

were also supported by a similar study in a human promyelocytic

leukemia cell line, HL-60 (25).

The mechanism underlying modifications of depletion of PSD reducing

apoptosis is not clear. One possibility is that Fas-induced

apoptosis is mediated by the activation of a Ras-related C3

botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1), and PSD can regulate Rac1

(26,27). Rac1 plays a pivotal role in

inducing apoptosis in response to stimuli such as UV light

(28), tumor necrosis factor-α

(16) and Fas (15). These findings strongly support our

data showing that PSD silencing can inhibited Rac1-mediated

apoptosis in siPSD-treated SGC7901 cells.

This is believed to be the first report of the

tumor-suppressor functions of PSD, which are epigenetically

silenced in GC, while silencing of PSD after transfection with

siRNA promotes GC progression. These findings provide new targets

for prognosis and pharmacological intervention in human GC.

Therefore, further in vitro and in vivo studies are

needed to determine the precise mechanism of PSD in the progression

of GC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by a grant from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 30572162),

the Foundation of Liaoning Province Science and Technology Plan

Project (grant no. 2013225021) and the Higher Specialized Research

Fund for Doctoral Program of Ministry of Education of China (grant

no. 20102104110001).

References

|

1

|

Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward

E and Forman D: Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin.

61:69–90. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Park YS, Jin MY, Kim YJ, Yook JH, Kim BS

and Jang SJ: The global histone modificaton pattern correlates with

cancer recurrence and overall survival in gastric adenocarcinoma.

Ann Surg Oncol. 15:1968–1976. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Meng CF, Zhu XJ, Peng G and Dai DQ: Role

of histone modifications and DNA methylation in the regulation of

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene expression

in human stomach cancer cells. Cancer Invest. 28:331–339. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kim M, Jang HR, Kim JH, et al: Epigenetic

inactivation of protein kinase D1 in gastric cancer andits role in

gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. Carcinogenesis.

29:629–637. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jaenisch R and Bird A: Epigenetic

regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic

and environmental signals. Nat Genet. 33:245–254. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Sharma S, Kelly TK and Jones PA:

Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 31:27–36. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD,

Turner BM, Eisenman RN and Bird A: Transcriptional repression by

the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase

complex. Nature. 393:386–389. 1998. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Hendrich B and Bird A: Identification and

characterization of a family of mammalian methyl-CpG binding

proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 18:6538–6547. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Bird A: DNA methylation patterns and

epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 16:6–21. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Tariq M, Saze H, Probst AV, Lichota J,

Habu Y and Paszkowski J: Erasure of CpG methylation in arabidopsis

alters patterns of histone H3 methylation in heterochromatin. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 100:8823–8827. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Espada J, Ballestar E, Fraga MF, et al:

Human DNA methyltransferase 1 is required for maintenance of the

histone H3 modification pattern. J Biol Chem. 279:37175–37184.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Meng CF, Zhu XJ, Peng G and Dai DQ:

Promoter histone H3 lysine 9 di-methylation is associated with DNA

methylation and aberrant expression of p16 in gastric cancer cells.

Oncol Rep. 22:1221–1227. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Kondo Y, Shen L, Yan PS, Huang TH and Issa

JP: Chromatin immunoprecipitation microarrays for identification of

genes silenced by histone H3 lysine 9 methylation. Proc Natl Acad

Sci USA. 101:7398–7403. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Rubinek T1, Shulman M, Israeli S, et al:

Epigenetic silencing of the tumor suppressor klotho in human breast

cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 133:649–657. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Gulbins E, Coggeshall KM, Brenner B,

Schlottmann K, Linderkamp O and Lang F: Fas-induced apoptosis is

mediated by activation of a Ras and Rac protein-regulated signaling

pathway. J Biol Chem. 271:26389–26394. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Esteve P, Embade N, Perona R, et al:

Rho-regulated signals induce apoptosis in vitro and in vivo by a

p53-independent, but Bcl2 dependent pathway. Oncogene.

17:1855–1869. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Perletti L, Talarico D, Trecca D,

Ronchetti D and Fracchiolla NS: Identification of a novel gene,

PSD, adjacent to NFKB2/lyt-10, which contains Sec7 and

pleckstrin-homologydomains. Genomics. 46:251–259. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Okada S, Suzuki K, Takaharu K, et al:

Aberrant methylation of the Pleckstrin and Sec7 domain-containing

gene is implicated in ulcerative colitis-associated carcinogenesis

throughits inhibitory effect on apoptosis. Int J Oncol. 40:686–694.

2012.

|

|

19

|

Fahrner JA, Eguchi S, Herman JG and Baylin

SB: Dependence of histone modifications and gene expression on DNA

hypermethylation in cancer. Cancer Res. 62:7213–7218.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Cameron EE, Bachman KE, Myohane S, Herman

JG and Baylin SB: Synergy of demethylation and histone deacetylase

inhibition in the re-expression of genes silenced in cancer. Nat

Genet. 21:103–107. 1999. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li LC and Dahiya R: MethPrimer: designing

primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 18:1427–1431. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Fuks F: DNA methylation and histone

modifications: teaming up to silence genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev.

15:490–495. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wu J, Wang SH, Potter D, et al: Diverse

histone modifications on histone 3 lysine 9 andtheir relation to

DNA methylation in specifying gene silencing. BMC Genomics.

8:1312007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Liu J, Zhu X, Xu X and Dai D: DNA promoter

and histone H3 methylation downregulate NGX6 in gastric cancer

cells. Med Oncol. 31:8172014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kato T, Suzuki K, Okada S, et al: Aberrant

methylation of PSD disturbs. Rac1-mediated immune responses

governing neutrophil chemotaxis and apoptosis in ulcerative

colitis-associated carcinogenesis. Int J Oncol. 40:942–950.

2012.

|

|

26

|

Saez R, Chan AM, Miki T and Aaronson SA:

Oncogenic activation of human R-ras by point mutations analogous to

those of prototype H-ras oncogenes. Oncogene. 9:2977–2982.

1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Nishida K, Kaziro Y and Satoh T:

Anti-apoptotic function of Rac in hematopoietic cells. Oncogene.

18:407–415. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Eom YW, Yoo MH, Woo CH, et al: Implication

of the small GTPase Rac1 in the apoptosis induced by UV in Rat-2

fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 285:825–829. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|