Introduction

High-grade malignant gliomas are among the most

rapidly growing and lethal human tumors. Despite multimodal

therapies, the prognosis of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) remains

poor and the tumor inevitably recurs. The failure of therapeutic

treatments is mainly due to the diffusion modalities of the tumor

and to several resistance mechanisms of cancer cells, such as

elevated expression of drug efflux transporters (1–3),

reduced sensitivity to apoptotic signals and increased expression

of growth factors. A pivotal role in resistance is played by the

ability of tumor cells to repair DNA damage caused by radiation and

chemotherapeutic agents, through a DNA damage response (DDR)

cascade (4–8).

Multiple complex pathways occur in the eukaryotic

cells for the surveillance and repair of genetic material and cell

cycle control. To DNA damage the cancer cells respond with: i) cell

cycle arrest and lesion repair; ii) entry into apoptosis or other

cell deaths; iii) proliferation without repairing the damage

favouring the effects of more genetic mutations. In response to

genotoxic stress, cells do not progress through the cycle until the

stability of the DNA molecule is ensured: the MRN

(Mre11-Rad50-Nbs1) sensor complex recruits the protein kinases

ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) and ataxia telangiectasia

Rad3-related (ATR), that initiate a transduction cascade activating

downstream effectors, including H2AX histone, 53 binding protein 1

(53BP1) and the checkpoint kinases Checkpoint 1 (Chk1) and

Checkpoint 2 (Chk2). These last two molecules act as a molecular

switch determining, through phosphorylation of tumor suppressor

protein p53, cell cycle arrest in order to allow DNA damage repair

(Fig. 1A). If the damage is too

extensive, apoptosis is triggered (9). Double strand breaks (DSBs), the most

dangerous DNA lesions in mammalian cells, are repaired by two main

pathways: homologous recombination (HR) and non-homologous end

joining (NHEJ) (10,11). The former takes place only in

actively cycling cells, during the S/G2 phases and its key effector

is RAD51 protein. The latter occurs during G0/G1 phases and is

driven by DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), which consists of

a regulatory subunit (Ku70/Ku80 heterodimer) and a catalytic

subunit (DNA-PKcs) (Fig. 1A).

Glioma stem cells (GSCs), responsible for GBM growth

and recurrence, show a relative resistance to apoptosis and an

increased DNA repair capacity (12–14).

Thanks to preferential activation of DDR and to an increased

Chk1/Chk2 activity, a delayed cell cycle may be a major resistance

mechanism (7) and Chk1/Chk2

inhibition is reported to sensitize to radio-treatments (13).

Temozolomide (TMZ), doxorubicin (Dox) and paclitaxel

(PTX) are drugs commonly used in the clinical practice of solid

tumors. TMZ, an alkylating agent at present employed in the

standard therapy of GBM, induces methylation in multiple sites on

DNA. The O6-methylguanines (O6-meGs) are the

most cytotoxic adducts and are normally repaired by the

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT). The

hypermethylation of the MGMT promoter determines epigenetic

silencing of the protein and correlates with a better prognosis

(15). If the cell is

MGMT-deficient, a futile mismatch repair (MMR) cycle is triggered

with formation of DNA DSBs and activation of ATM/ATR-Chk1/Chk2

signaling, G2/M-cell cycle arrest and ultimately apoptosis

(16–18) (Fig.

1B). The anthracycline Dox interferes with cell growth by

intercalation between DNA paired bases, finally causing cell death.

PTX acts as antimitotic drug determining apoptosis. Also Dox and

PTX are reported to induce DNA strand breaks and a repair response

in some cell types (19,20); their use on brain tumors is limited

due to the poor blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetration capacity,

even though their in vitro effectiveness on GBM cells and in

glioma animal models is proven (21–23).

The present study explored the in vitro

effects of TMZ, Dox and PTX on primary GBM cell lines, focusing the

attention on TMZ and by investigating DNA damage extent and the

molecular mechanisms leading to a repair response, i.e., a

resistant phenotype, or to cell death.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, culture conditions and tumor

specimens

Primary human GBM cultures were established from

tumors surgically resected at the Department of Neurosurgery of CTO

Hospital (Turin, Italy). Malignant glioma U87-MG and 010627 cell

lines were kindly supplied by Dr Rossella Galli (DIBIT San

Raffaele, Milan, Italy). Ten cell lines were cultured, as

previously described (24), in

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F-12 supplemented with 20

ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF) and 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast

growth factor (bFGF) for neurosphere (NS) assay and 6 cell lines in

DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) for adherent

cell (AC) growth (Table I). Both

cultures were maintained at 37°C in 5% O2 and 5%

CO2. All cell lines were characterized for MGMT gene

promoter and p53 gene status (24,25)

(Table I). Experiments with

primary GBM lines were carried out using cells from passages 10–20

and cultures were checked for Mycoplasma contamination

before use (e-Myco™ Mycoplasma PCR Detection kit, iNtRON

Biotechnology, Korea). Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE)

brain tumor samples were collected from 8 GBMs, one pilocytic

astrocytoma and one oligodendroglioma. The histological diagnosis

was performed according to World Health Organization (WHO)

guidelines (26). The study was in

compliance with the local institutional review board and Committee

on Human Research and with the ethical human-subject standards of

the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki Research.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

| Table ICell lines with the IC50

values for each drug and the MGMT and p53 gene status. |

Table I

Cell lines with the IC50

values for each drug and the MGMT and p53 gene status.

| Cell line | IC50

(μM)a for TMZ | IC50

(μM)a for Dox | IC50

(μM)a for PTX | Methylation status

of MGMT promoter | Status of p53

gene |

|---|

| U87-MG NS | 170 | 0.92 | - | Methylated | Wild-type |

| 010627 NS | 135 | - | - | Methylated | Mutated |

| CV10 NS | 8.5 | - | - | Methylated | Wild-type |

| CV21 NS | 44 | 0.68 | 0.03 | Methylated | Wild-type |

| NO3 NS | 120 | 0.85 | 0.044 | Unmethylated | Wild-type |

| NO4 NS | 100 | 0.98 | 0.1 | Methylated | Mutated |

| NO6 NS | 170 | - | 0.0094 | Unmethylated | Wild-type |

| CTO3 NS | 97 | 1.85 | 0.066 | Methylated | Mutated |

| CTO5 NS | 130 | 1.18 | 0.08 | Unmethylated | Wild-type |

| CTO15 NS | 130 | 0.65 | 0.035 | Unmethylated | Mutated |

| U87-MG AC | 42 | 0.72 | - | Methylated | Wild-type |

| 010627 AC | 130 | - | - | Methylated | Mutated |

| CV10 AC | 5 | - | - | Methylated | Wild-type |

| NO3 AC | 72 | 0.78 | 0.05 | Unmethylated | Wild-type |

| CTO3 AC | 50 | 0.83 | 0.077 | Methylated | Mutated |

| CTO15 AC | 46 | 0.67 | 0.027 | Unmethylated | Mutated |

Drug treatment and cytotoxicity

assay

TMZ, Dox and PTX (all from Sigma-Aldrich Co., St.

Louis, MO, USA) were dissolved in 100% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) for

stock solutions. The final concentration of DMSO never exceeded

0.3% (v/v). All cell lines (10 NS and 6 AC) were treated with TMZ

at increasing doses (5, 50, 100, 200 and 500 μM) and times [6, 24,

48, 72 and 120 hours (h)]; eleven cell lines (7 NS and 4 AC) were

treated with 1, 2 and 5 μM Dox at 2, 24, 48 and 72 h; ten cell

lines (7 NS and 3 AC) were treated with 10, 100, 1,000 and 5,000 nM

PTX at 24, 48, 72 and 120 h. The drugs were added to dissociated NS

cultures. After exposure, the cytotoxicity of the drugs was

evaluated assessing the number of viable cells by the

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT)

assay (Roche, Diagnostic Corp., Indianapolis, IN, USA), measuring

optical density at 570 nm (test wavelength) and 660 nm (reference

wavelength) by a microplate spectrophotometer (Synergy HT, BioTek

Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). For NS, cell counts were also

performed by trypan blue using a TC20 automated cell counter

(Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA, USA). Cytotoxicity was expressed as number

of surviving cells as percentage of control (untreated cells). The

concentration of the drugs which caused a 50% inhibition of the

cell growth, defined IC50, was calculated for each cell

line at 72 h by non-linear regression from the survival curves of

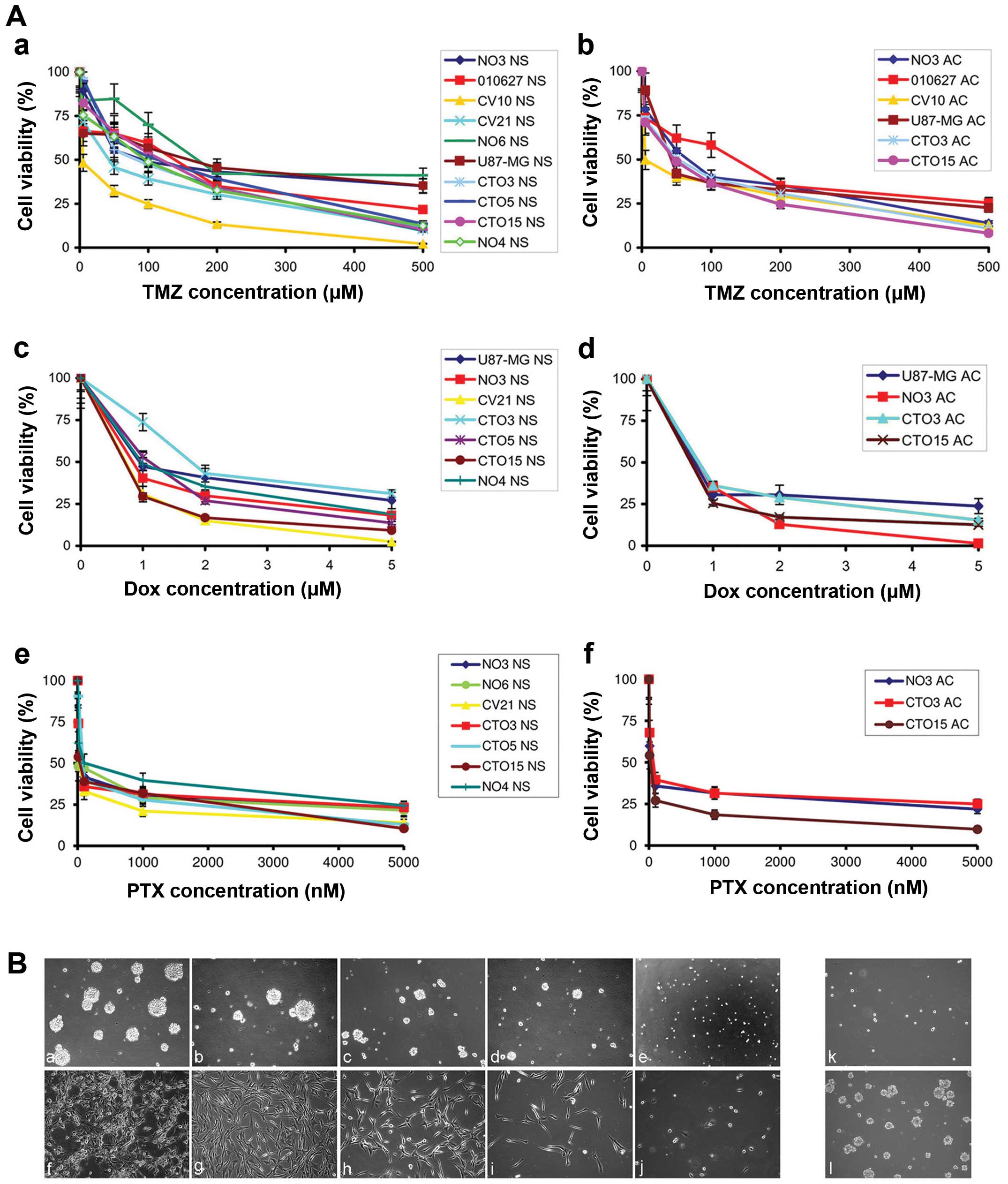

Fig. 2A.

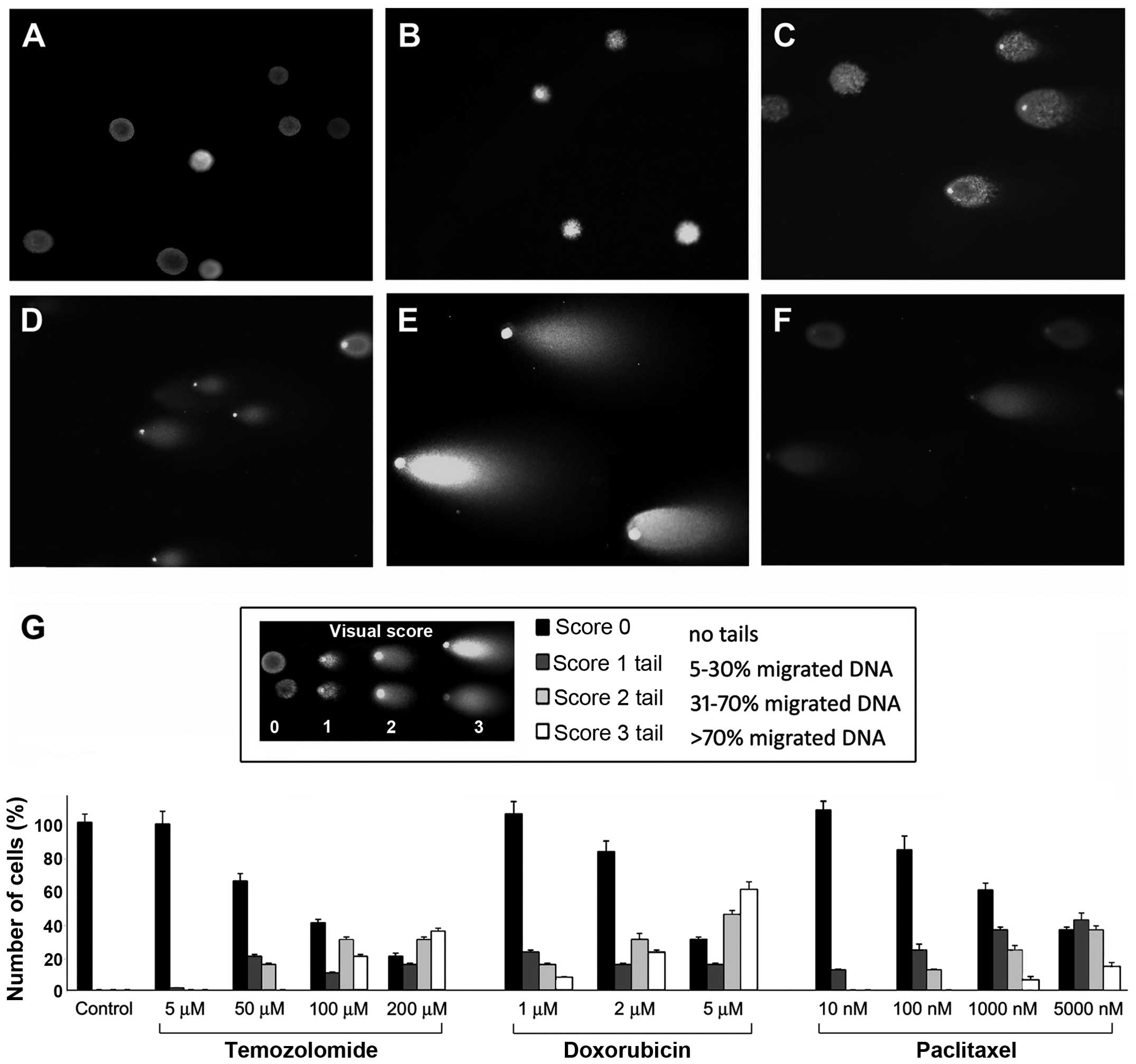

Comet assay

Cells were treated with different drug doses at

various time-points and the occurrence of DNA damage induced by the

drugs was investigated using the Comet (or single cell gel

electrophoresis, SCGE) assay kit (Trevigen Inc., Gaithersburg, MD,

USA) at neutral pH. Nuclei were labeled with SYBR Green I dye.

Observations were made on a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope

(Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) equipped with an AxioCam5 MR5c

and coupled to an Imaging system (AxioVision Release 4.5; Carl

Zeiss). Cleaved DNA fragments caused by DSBs are detected as a tail

(comet), the length of which is a measure of the DNA damage degree

(27). Cells with comet tails were

quantified as percentage over the total cell number and a visual

score was assigned to the comets (28): score 0 representing undamaged cells

(comets with no or barely detectable tails); score 1, 5–30% of

migrated DNA; score 2, 31–70% of migrated DNA; score 3, >70% of

migrated DNA (panel in Fig.

3G).

Determination of apoptosis

Apoptosis was evaluated on cells after treatment

with TMZ and PTX and on tissue sections by in situ terminal

deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling

(TUNEL) assay, using the in situ cell death detection kit,

fluorescein (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Apoptotic indexes were calculated scoring 4 randomly selected

fields and counting number of apoptotic cells over the total of

viable cells which represented a quota in comparison with untreated

cells.

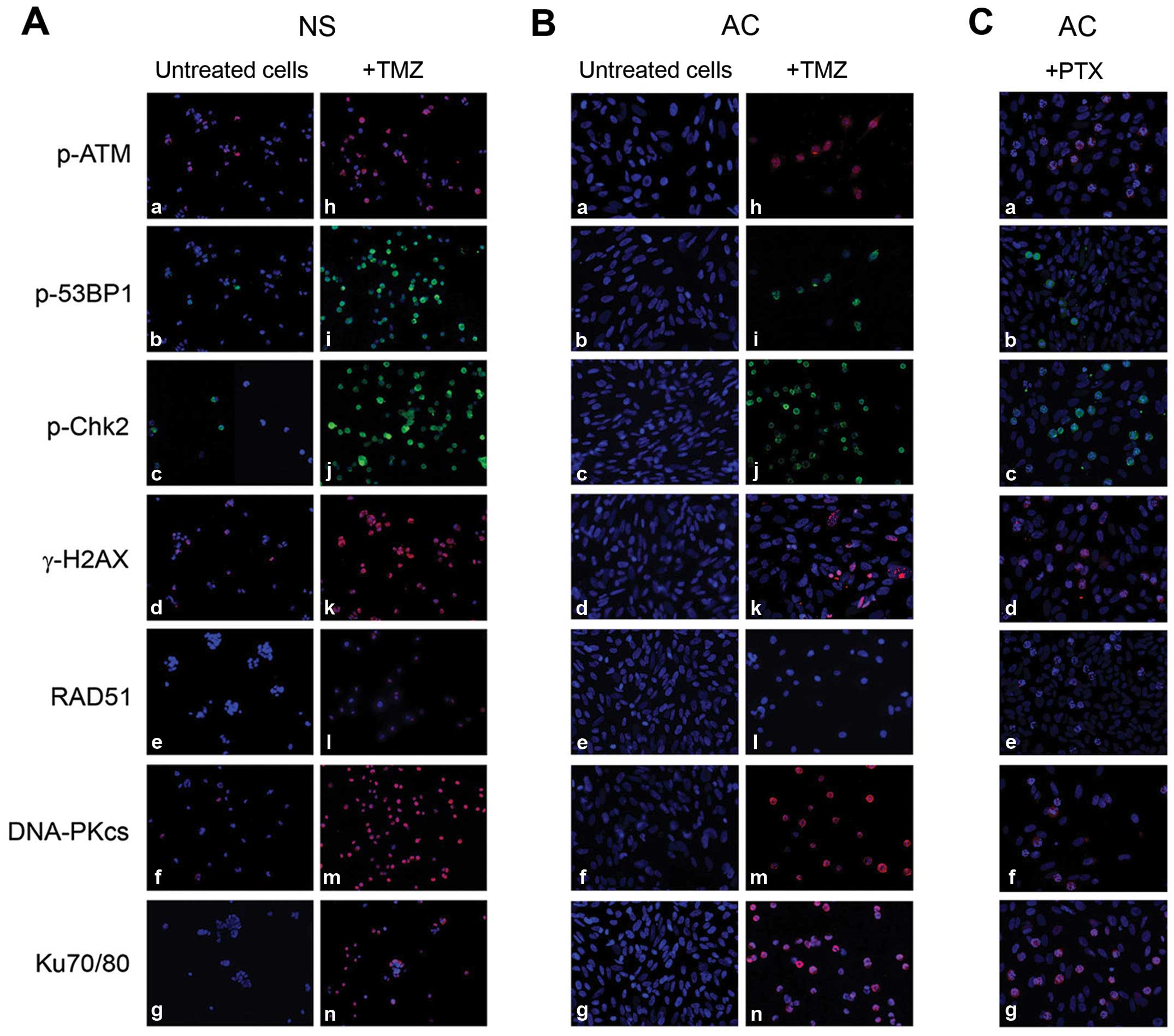

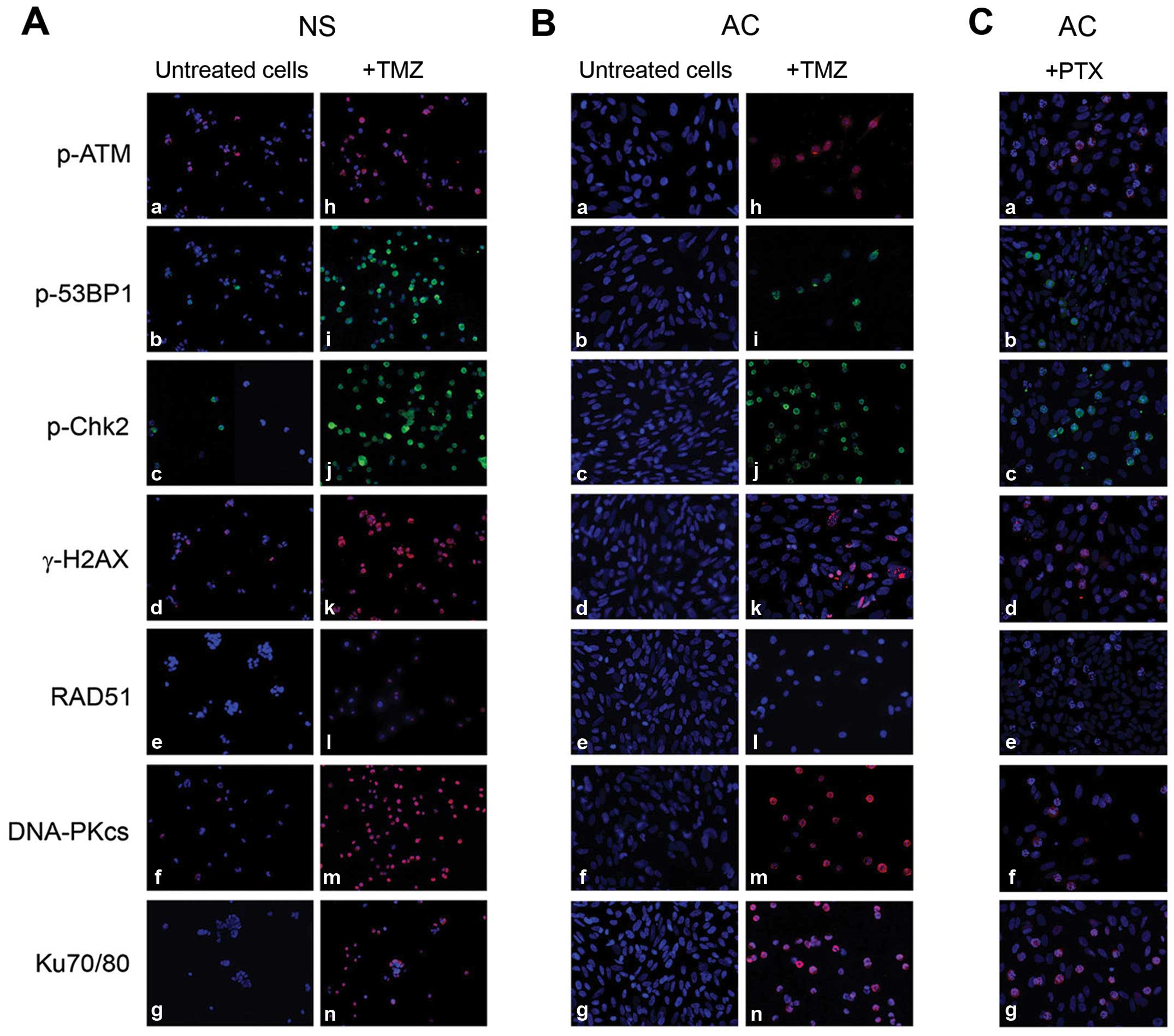

Immunofluorescence (IF)

IF was performed on NS and AC following TMZ and PTX

treatments to monitor the activation of the damage/repair molecules

p-ATM, p-Chk2, p-53BP1, γ-H2AX histone, HR effector RAD51, NHEJ

effectors Ku70/Ku80 and DNA-PKcs. Cells were fixed for 20 min with

4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, rinsed three times with

PBS, blocked/permeabilized for 30 min with PBS containing 2% of the

appropriate serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 and finally stained with

the following primary antibodies: monoclonal mouse anti-human

γ-H2AX (Ser139) (05-636; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA; dilution

1:200), monoclonal mouse anti-human p-ATM (Ser1981) (05-740;

Millipore; dilution 1:100), polyclonal rabbit anti-human p-Chk2

(Thr68) (BK2197S; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA;

dilution 1:100), polyclonal rabbit anti-human p-53BP1 (Ser25)

(IHC-00053; Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA;

dilution 1:200), monoclonal mouse anti-human RAD51 (MS-988;

NeoMarkers, Fremont, CA, USA; dilution 1:100), monoclonal mouse

anti-human DNA-PKcs (MS-423; NeoMarkers; dilution 1:100) and

monoclonal mouse anti-human Ku70/Ku80 (MS-286; NeoMarkers; dilution

1:200). Negative controls were obtained by omitting the primary

antibody. Alexa Fluor® 488-AffiniPure goat anti-rabbit

IgG and Alexa Fluor® 594-AffiniPure rabbit anti-mouse

IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, PA,

USA) were used as secondary antibodies. Cell nuclei were stained

with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and examined under a

Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope.

Immunocytochemistry (ICC) and

ımmunohistochemistry (IHC)

Due to the interfering spontaneous fluorescence of

Dox, ICC, instead of IF, was carried out on cells treated with Dox.

IHC was performed on the 8 GBM and 2 low-grade tissues. The

analyses were made using a Ventana Full BenchMark® XT

automated immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, AZ,

USA) and UltraView™ Universal DAB Detection kit (Ventana Medical

Systems Inc.) as detection system. Heat-induced epitope retrieval

(HIER) was performed in Tris-EDTA, pH 8.0. Primary antibodies were

the same used for IF with the same dilutions. Negative controls

were obtained by omitting the primary antibody.

Western blotting (WB)

WB was performed as previously described (24) using the following primary

antibodies: monoclonal mouse anti-human γ-H2AX (Ser139) (05-636;

Millipore; dilution 1:1,000), monoclonal mouse anti-human p-ATM

(Ser1981) (05-740; Millipore; dilution 1:2,000), polyclonal rabbit

anti-human p-Chk2 (Thr68) (BK2197S; Cell Signaling Technology;

dilution 1:1,000), monoclonal mouse anti-human RAD51 (MS-988;

NeoMarkers; dilution 1:500), and monoclonal mouse anti-human

Ku70/Ku80 (MS-286; NeoMarkers; dilution 1:1,000). A polyclonal

rabbit anti-human α-tubulin (LF-PA0146; LabFrontier, Seoul, Korea;

dilution 1:5,000) was used to normalize sample loading and

transfer.

Statistical analysis

The level of significance was determined by a

two-tailed Student’s t-test. All quantitative data presented are

the average value ± standard error (SE) from at least three

independent determinations. Statistical significance was defined as

p<0.05 or p<0.01.

Results

Cytotoxicity studies on GBM cell lines

after TMZ, Dox and PTX treatments

NS lines were self-renewing, clonogenic, multipotent

and expressing undifferentiation antigens; AC displayed a

differentiation antigen profile (24). TMZ, Dox and PTX inhibited cell

proliferation, both in NS and in AC by MTT assay, controlled by

trypan blue method. The cytotoxic effect of the three drugs were

dose- and time-dependent and more evident on AC than on NS

(Fig. 2A-a-f). NS were resistant

to dosages of TMZ <10 μM, with the exception of CV10 and CV21

lines, that presented hypermethylation of MGMT promoter (Table I). Even high TMZ concentrations

resulted in the survival of ≤30% of the cells in some NS lines. On

the contrary, on most AC, TMZ concentrations <50 μM reduced cell

growth to 50% after 72-h exposure. Compared with growth of

untreated NS and AC (Fig. 2B-a and

-f, respectively, from NO3 cell line, taken as a representative

line), cell proliferation in NS (Fig.

2B-b-e) and AC adhesion (Fig.

2B-g-j) was hindered by TMZ in a dose and time-dependent

manner. However, the growth inhibition in NS was not irreversible

and the depletion of cells was not complete, even at high drug

dosages. Even after 5-day treatment with high TMZ dosage (200 μM),

a few single cells survived re-acquiring growth capacity within one

month after treatment suspension (Fig.

2B-k and -l).

Dox uptake by NS and AC was evident in most cells

already after 2 h with 2 μM drug and, after 24-h exposure, the

number of viable cells showed 20% decrease with inhibition of

clonogenicity in NS and of cell adhesion in AC. After 72-h

treatment, 80% cells were dead. Also 100 nM PTX at 48 h inhibited

evidently cell proliferation both in NS and in AC. After 5-day

treatment a few single cells of NS lines survived re-acquiring

growth capacity within one month after treatment suspension.

Evaluation of DNA damage by Comet

assay

By Comet assay no damage was detectable on untreated

NS (Fig. 3A) and AC (data not

shown) and on NS treated with 50 μM TMZ for 24 h (Fig. 3B); a comet tail was evident only

after 72-h exposure with 50 μM drug (Fig. 3C): >10% of cells showed a

score-2-length tail. Comets with score-3 length were visible in

>50% of cells treated with 200 μM TMZ (Fig. 3D). The damage resulted more

elevated in AC and in NS lines with methylated MGMT promoter. DNA

lesions were revealed in NS (Fig.

3E) and even more in AC (data not shown) with 2 μM Dox at 72 h

and the same effect but weaker was observed after 72-h treatment

with 100 nM PTX both in NS (Fig.

3F) and in AC (data not shown) with score-2 length tails.

Quantification of cell damage by Comet assay in untreated and

treated NO3 NS is reported in Fig.

3G.

Determination of cell apoptosis induced

by drug treatment

Apoptosis was a late phenomenon, evident only after

72-h drug exposure, both in NS and AC (Fig. 4A and B). The frequency of apoptotic

cells following treatment with increasing concentrations of TMZ for

6, 24 and 72 h is shown in Fig. 4C and

D for NS and AC, respectively. In treated NS, apoptosis did not

exceed 10–15% and it was ≤30% in AC. PTX-induced apoptosis was

evidenced at 72 h already at concentration of 10 nM. At the highest

drug dosages, the percentage of apoptotic cells was ≤20% in NS

(Fig. 4E) and ≤30% in AC (Fig. 4F).

Studies of checkpoint/repair pathways in

treated cells

The antigens of repair cascade resulted negative in

untreated NS, with the exception of p-ATM, γ-H2AX, Ku70/Ku80,

DNA-PKcs, moderately expressed in some lines (Fig. 5A-a-g). No expression was shown in

untreated AC (Fig. 5B-a-g). The

expression of all the sensors and effectors, except RAD51, was

evident after 48-h exposure to 100 μM TMZ, both in NS and, at a

minor extent, in AC (Fig. 5A and

B-h-n). Expression of p-ATM, γ-H2AX, p-Chk2, Ku70/80 and RAD51

in 4 NS lines treated with TMZ was confirmed by WB analysis

(Fig. 5D). Dox effects were the

same as TMZ but earlier. γ-H2AX, indicator of DSBs, was evident

after 48-h treatment with 50 μM TMZ or 5 μM Dox, both in NS and in

AC. Concurrent administration of the two drugs increased the effect

with γ-H2AX expressed in ~90% of cells and a significant decrease

in cell number (Fig. 5E-a-d for NS and

-e-h for AC). All repair markers became negative after 72 h

with high drug concentrations (500 μM TMZ or 5 μM Dox): cells were

dying or no longer able to activate the repair cascade. After 72-h

treatment with 100 nM PTX, a moderate activation of

checkpoint/repair response with a mild expression of all markers

except RAD51 was found in NS, whereas, interestingly, in treated

AC, several cells appeared arrested in metaphase and with a strong

expression of p-ATM, p-Chk2, p-53BP1, γ-H2AX, DNA-PKcs, Ku70/Ku80

(Fig. 5C-a-g). After 24 h from the

beginning of treatments, the presence of activated damage sensors

(p-ATM, p-53BP1, γ-H2AX, p-Chk2) was more evident, whereas at

longer times (72 h), expression level of effectors (DNA-PKcs,

Ku70/80) increased and that of sensor molecules decreased as repair

proceeded (Fig. 5F).

| Figure 5Study of checkpoint/repair response

in NO3 NS and AC. (A) Expression by immunofluorescence of

checkpoint/repair proteins in untreated NO3 NS (a-g) and in cells

treated with 100 μM TMZ for 48 h (h-n). (B) The same as above in

untreated (a-g) and treated NO3 AC (h-n). (C) The same as above in

NO3 AC treated with 100 nM PTX for 72 h (a-g): positivity of the

antigens is evident at metaphasis level. Nuclei counterstained with

DAPI. All ×200 magnification. (D) Expression by western blotting of

p-ATM, p-Chk2, γ-H2AX and Ku70/Ku80 in 4 NS lines (CV10, 010627,

CV21 and NO3), untreated and treated with 100 μM TMZ for 48 h. No

band for RAD51 was detectable in any lines, not even after TMZ

treatment. (E) Expression by immunocytochemistry of γ-H2AX, as

indicator of DNA damage, in untreated NO3 NS (a, ×400) and AC (e,

×400) and after 50 μM TMZ for 48 h [(b) and (f) for NS and AC,

respectively, ×400], after 5 μM Dox for 48 h [(c) and (g) for NS

and AC, respectively, ×400] and after combined treatment with 50 μM

TMZ and 5 μM Dox for 48 h [(d) and (h) for NS and AC, ×400 and

×630, respectively]. (F) Levels of checkpoint/repair proteins at 24

(a) and 72 h (b) in NO3 NS, untreated (control) and treated with

100 μM TMZ, 2 μM Dox or 100 nM PTX. |

Studies of checkpoint/repair and

apoptosis in glioma tissues

p-ATM, γ-H2AX and the key proteins of NHEJ system,

DNA-PKcs and Ku70/Ku80, were constitutively expressed in the GBM

specimens studied, particularly in proliferation areas and in

perinecrotic pseudopalisades (Fig.

6A-a, -b, -e and -f). p-ATM and γ-H2AX were sometimes positive

in macrophages and reactive astrocytes. p-Chk2 and RAD51 expression

was rather scarce and heterogeneous (Fig. 6A-c and -d) and p-53BP1 was not

detectable. The two low-grade glioma tissues analyzed were almost

negative for the markers, with the exception of p-ATM and γ-H2AX,

poorly positive at level of mitoses (Fig. 6B). Apoptosis occurred in the

palisades of circumscribed necroses and was scattered in the

proliferating areas of GBM (29)

(Fig. 6C).

| Figure 6(A) Immunohistochemical expression in

GBM tissues of p-ATM, DAB, ×200 (a); γ-H2AX, DAB, ×200 (b); p-Chk2,

DAB, ×400 (c); RAD51, positive in scattered cells, DAB, ×400 (d);

DNA-PKcs, DAB, ×200 (e); Ku70/Ku80, DAB, ×200 (f). (B)

Immunohistochemical expression of p-ATM in a pilocytic astrocytoma,

DAB, ×400 (a); γ-H2AX in an oligodendroglioma, DAB, ×200 (b);

p-Chk2 in an oligodendroglioma, DAB, ×400 (c); RAD51 in an

oligodendroglioma, DAB, ×400 (d); DNA-PKcs in an oligodendroglioma,

DAB, ×200 (e); Ku70/Ku80 in an oligodendroglioma, DAB, ×200 (f).

(C) Evaluation of apoptosis in GBM tissue sections. Scattered

apoptotic nuclei in palisades of circumscribed necroses (a) and in

proliferating areas (b) of a GBM sample, TUNEL labeling, ×400. |

Discussion

In this study we demonstrated that three commonly

used anticancer drugs, TMZ, Dox and PTX, were able, under in

vitro conditions, to reduce significantly the number of viable

cells in GBM NS lines and even more in AC lines, inhibiting

clonogenic growth in the former and hindering cell adhesion in the

latter. The finding, as for TMZ, is in agreement with recent

reports (30,31). Dox and PTX caused a more evident

reduction of cell viability in comparison with TMZ, both in NS and

in AC. IC50 values for TMZ and Dox at 72 h were, on

average, higher for NS than for AC, proving that the former are

more resistant than the latter, characterized by a more

differentiated state. No significant differences in IC50

values for PTX was observed between NS and AC.

Cell lines with a hypermethylated MGMT promoter were

mostly more sensitive to TMZ, but the data were in some cases

discordant. MGMT expression indeed is not the only factor to be

considered in evaluating TMZ response: p53 wild-type status is

reported as fundamental to determine cell cycle arrest and the

entry in the apoptotic process (32,33).

In our data, among the cell lines with hypermethylated MGMT those

with mutated p53 gene appeared more resistant to the action of TMZ

than the ones with wild-type p53.

In NS cultures treated with TMZ or PTX, the

depletion of cells was never complete even at high drug dosages;

cells could resist the drugs in a non-proliferating state, as

already observed for TMZ (30,31)

and resumed proliferation within 1–2 months after treatment

suspension. The maintenance of a quiescent state and metabolic

inertia may, therefore, represent a mechanism of genome protection

in GSCs; the consequence is that antineoplastic treatments can have

a cytostatic rather than a cytotoxic effect. Dox effect was more

lethal and irreversible.

Apoptosis following treatments was a late phenomenon

demonstrable only after 72 h, as already reported (18,34).

In our observations, it was more evident in AC than in NS, but in

both cases the frequency of apoptosis does not explain the level of

reduction of viable cells, in agreement with the data of Beier

et al (35).

By Comet assay we found that TMZ, Dox and, to lesser

extent, PTX were able to produce in glioma cells a DNA damage, that

increased proportionally with drug doses and times and was higher

in AC than in NS lines, with the consequent activation of the

checkpoint/repair pathways. Moreover, we noted in some untreated NS

lines a basal expression of some checkpoint/repair proteins, which

was significantly elicited following drug exposure. After DNA

injury also AC were able to trigger a repair response, although to

a minor extent. Sensors of damage were the first proteins to be

activated and they decreased with time, as the effectors increased

and repair of lesions took place. From our data, NHEJ repair system

activity seemed higher than the one of HR. It was reported that

high tumor levels of DNA-PK correlate with poor survival in GBM

patients treated with postsurgical radiation (36).

In GBM tissue specimens, we found a constitutive

expression of checkpoint/repair proteins, not present in the

low-grade tumors. At the beginning of tumorigenesis, DDR machinery

acts as a protective mechanism against glioma progression, limiting

the expansion of malignant clones with unstable genome (37). In glioma pathogenesis an aberrant

constitutive activation of repair mechanisms was reported in

response to DNA replication stress produced by oncogenes (38).

In conclusion, cell fate after treatments depends on

the preferential activation of repair or apoptotic pathways. The

intrinsic resistance to genotoxic therapies of malignant glioma

cells could therefore be explained on one hand, by their ability to

stop growth and survive in a quiescent state and, on the other

hand, by the involvement of an enhanced DNA damage signaling.

Moreover, we demonstrated that also Dox and PTX would be effective

cytotoxic/cytostatic agents, similarly to TMZ, on glioma cells and,

once the way to cross the BBB is found (39,40),

they could be potentially useful in the GBM treatment. Targeted

inhibition of the DNA repair factors could, therefore, be useful to

sensitize malignant gliomas to genotoxic treatments and to improve

therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Grant ID ORTO11WNST and

by Grant no. 4011 SD/cv 2011-0438, both from Compagnia di San

Paolo, Turin, Italy.

References

|

1

|

Caldera V, Mellai M, Annovazzi L,

Monzeglio O, Piazzi A and Schiffer D: MGMT hypermethylation and MDR

system in glioblastoma cancer stem cells. Cancer Genomics

Proteomics. 9:171–178. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Salmaggi A, Boiardi A, Gelati M, Russo A,

Calatozzolo C, Ciusani E, Sciacca FL, Ottolina A, Parati EA, La

Porta C, Alessandri G, Marras C, Croci D and De Rossi M:

Glioblastoma-derived tumorospheres identify a population of tumor

stem-like cells with angiogenic potential and enhanced multidrug

resistance phenotype. Glia. 54:850–860. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Johannessen TC and Bjerkvig R: Molecular

mechanisms of temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma multiforme.

Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 12:635–642. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Alexander BM, Pinnell N, Wen PY and

D’Andrea A: Targeting DNA repair and the cell cycle in

glioblastoma. J Neurooncol. 107:463–477. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Schmalz PG, Shen MJ and Park JK: Treatment

resistance mechanisms of malignant glioma tumor stem cells. Cancers

(Basel). 3:621–635. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Frosina G: The bright and the dark sides

of DNA repair in stem cells. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010:8453962010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Frosina G: DNA repair and resistance of

gliomas to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Mol Cancer Res.

7:989–999. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sarkaria JN, Kitange GJ, James CD, Plummer

R, Calvert H, Weller M and Wick W: Mechanisms of chemoresistance to

alkylating agents in malignant glioma. Clin Cancer Res.

14:2900–2908. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kastan MB and Bartek J: Cell-cycle

checkpoints and cancer. Nature. 432:316–323. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Bolderson E, Richard DJ, Zhou BB and

Khanna KK: Recent advances in cancer therapy targeting proteins

involved in DNA double-strand break repair. Clin Cancer Res.

15:6314–6320. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pardo B, Gómez-González B and Aguilera A:

DNA repair in mammalian cells: DNA double-strand break repair: how

to fix a broken relationship. Cell Mol Life Sci. 66:1039–1056.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Johannessen TC, Bjerkvig R and Tysnes BB:

DNA repair and cancer stem-like cells--potential partners in glioma

drug resistance? Cancer Treat Rev. 34:558–567. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q,

Hjelmeland AB, Dewhirst MW, Bigner DD and Rich JN: Glioma stem

cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA

damage response. Nature. 444:756–760. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Liu G, Yuan X, Zeng Z, Tunici P, Ng H,

Abdulkadir IR, Lu L, Irvin D, Black KL and Yu JS: Analysis of gene

expression and chemoresistance of CD133+ cancer stem

cells in glioblastoma. Mol Cancer. 5:672006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hegi ME, Diserens AC, Gorlia T, Hamou MF,

de Tribolet N, Weller M, Kros JM, Hainfellner JA, Mason W, Mariani

L, et al: MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in

glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 352:997–1003. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Hirose Y, Berger MS and Pieper RO: p53

effects both the duration of G2/M arrest and the fate of

temozolomide-treated human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res.

61:1957–1963. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Günther W, Pawlak E, Damasceno R, Arnold H

and Terzis AJ: Temozolomide induces apoptosis and senescence in

glioma cells cultured as multicellular spheroids. Br J Cancer.

88:463–469. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Roos WP, Batista LF, Naumann SC, Wick W,

Weller M, Menck CF and Kaina B: Apoptosis in malignant glioma cells

triggered by the temozolomide-induced DNA lesion O6-methylguanine.

Oncogene. 26:186–197. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kurz EU, Douglas P and Lees-Miller SP:

Doxorubicin activates ATM-dependent phosphorylation of multiple

downstream targets in part through the generation of reactive

oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 279:53272–53281. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Branham MT, Nadin SB, Vargas-Roig LM and

Ciocca DR: DNA damage induced by paclitaxel and DNA repair

capability of peripheral blood lymphocytes as evaluated by the

alkaline comet assay. Mutat Res. 560:11–17. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Stan AC, Casares S, Radu D, Walter GF and

Brumeanu TD: Doxorubicin-induced cell death in highly invasive

human gliomas. Anticancer Res. 19(2A): 941–950. 1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lesniak MS, Upadhyay U, Goodwin R, Tyler B

and Brem H: Local delivery of doxorubicin for the treatment of

malignant brain tumors in rats. Anticancer Res. 25(6B): 3825–3831.

2005.Erratum in: Anticancer Res 26: 445, 2006. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Chang SM, Kuhn JG, Robins HI, Schold SC

Jr, Spence AM, Berger MS, Mehta M, Pollack IF, Rankin C and Prados

MD: A Phase II study of paclitaxel in patients with recurrent

malignant glioma using different doses depending upon the

concomitant use of anticonvulsants: A North American Brain Tumor

Consortium report. Cancer. 91:417–422. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Caldera V, Mellai M, Annovazzi L, Piazzi

A, Lanotte M, Cassoni P and Schiffer D: Antigenic and genotypic

similarity between primary glioblastomas and their derived

neurospheres. J Oncol. 2011:3149622011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Mellai M, Monzeglio O, Piazzi A, Caldera

V, Annovazzi L, Cassoni P, Valente G, Cordera S, Mocellini C and

Schiffer D: MGMT promoter hypermethylation and its associations

with genetic alterations in a series of 350 brain tumors. J

Neurooncol. 107:617–631. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD and

Cavanee WK: WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous

Systems. 4th edition. International Agency for Research on Cancer

(IARC); Lyon: 2007

|

|

27

|

Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RR and Schneider

EL: A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage

in individual cells. Exp Cell Res. 175:184–191. 1988. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Collins AR, Oscoz AA, Brunborg G, Gaivão

I, Giovannelli L, Kruszewski M, Smith CC and Stetina R: The comet

assay: Topical issues. Mutagenesis. 23:143–151. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Mellai M and Schiffer D: Apoptosis in

brain tumors: Prognostic and therapeutic considerations. Anticancer

Res. 27(1A): 437–448. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Beier D, Röhrl S, Pillai DR, Schwarz S,

Kunz-Schughart LA, Leukel P, Proescholdt M, Brawanski A, Bogdahn U,

Trampe-Kieslich A, et al: Temozolomide preferentially depletes

cancer stem cells in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 68:5706–5715. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Mihaliak AM, Gilbert CA, Li L, Daou MC,

Moser RP, Reeves A, Cochran BH and Ross AH: Clinically relevant

doses of chemotherapy agents reversibly block formation of

glioblastoma neurospheres. Cancer Lett. 296:168–177. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hermisson M, Klumpp A, Wick W, Wischhusen

J, Nagel G, Roos W, Kaina B and Weller M: O6-methylguanine DNA

methyltransferase and p53 status predict temozolomide sensitivity

in human malignant glioma cells. J Neurochem. 96:766–776. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Bocangel DB, Finkelstein S, Schold SC,

Bhakat KK, Mitra S and Kokkinakis DM: Multifaceted resistance of

gliomas to temozolomide. Clin Cancer Res. 8:2725–2734.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Knizhnik AV, Roos WP, Nikolova T, Quiros

S, Tomaszowski KH, Christmann M and Kaina B: Survival and death

strategies in glioma cells: Autophagy, senescence and apoptosis

triggered by a single type of temozolomide-induced DNA damage. PLoS

One. 8:e556652013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Beier D, Schriefer B, Brawanski K, Hau P,

Weis J, Schulz JB and Beier CP: Efficacy of clinically relevant

temozolomide dosing schemes in glioblastoma cancer stem cell lines.

J Neurooncol. 109:45–52. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Kase M, Vardja M, Lipping A, Asser T and

Jaal J: Impact of PARP-1 and DNA-PK expression on survival in

patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Radiother Oncol.

101:127–131. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Bartek J, Bartkova J and Lukas J: DNA

damage signalling guards against activated oncogenes and tumour

progression. Oncogene. 26:7773–7779. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Bartkova J, Hamerlik P, Stockhausen MT,

Ehrmann J, Hlobilkova A, Laursen H, Kalita O, Kolar Z, Poulsen HS,

Broholm H, et al: Replication stress and oxidative damage

contribute to aberrant constitutive activation of DNA damage

signalling in human gliomas. Oncogene. 29:5095–5102. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Battaglia L, Gallarate M, Peira E, Chirio

D, Muntoni E, Biasibetti E, Capucchio MT, Valazza A, Panciani PP,

Lanotte M, et al: Solid lipid nanoparticles for potential

doxorubicin delivery in glioblastoma treatment: Preliminary in

vitro studies. J Pharm Sci. 103:2157–2165. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Chirio D, Gallarate M, Peira E, Battaglia

L, Muntoni E, Riganti C, Biasibetti E, Capucchio MT, Valazza A,

Panciani P, et al: Positive-charged solid lipid nanoparticles as

paclitaxel drug delivery system in glioblastoma treatment. Eur J

Pharm Biopharm. 88:746–758. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|