Introduction

Kidney cancer, one of the most common malignancies

in genitourinary system, affects approximately 208,500 people all

around the world each year. In addition, the global incidence of

kidney cancer is continuously increasing (1). Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is

identified as the most common type of kidney cancer, which is

responsible for approximately 90–95% of primary kidney cancer cases

(2). RCC starts in the cells of

the proximal renal tubular epithelium, with classic symptoms

including haematuria, flank pain and an abdominal mass. Although

smoking, NSAIDs medication and family history are suggested as risk

factors, the exact pathogenies of RCC remain poorly understood

(3,4). Besides, the therapy for RCC is still

limited. Surgery is applied primarily in RCC treatment, as RCC is

often insensitive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Whereas,

surgery is not always efficient when the cancer has spread around

the body. In recent years, target therapy has improved the

treatment of RCC (5).

Neutralization of vascular endothelial growth factor is proved to

prolong the time to progression of disease in RCC patients. Thus,

the research on potential targeting factors may light up the

prospect for RCC treatment.

The transmembrane glycoproteins of triggering

receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM) belong to the single

immunoglobulin variable (IgV) domain receptor family (6). TREMs map to human chromosome 6p21.1

and encode TREM-1, TREM-2, TREM-4, TREM-5 and TREM-like genes in

human. TREM-2 is encoded by a 1041-nucleotide long cDNA. This

receptor consists of an extracellular domain, a transmembrane

region and a short cytoplasmic tail (7,8).

TREM-2 is involved in many biological processes (9). In bone remodeling, TREM-2 has been

suggested to favor osteoclast differentiation and morphology

(10). In immune responses, TREM-2

is associated with the upregulation of CD40, CD86, MHC class II in

dendritic cells and the maturation of dendritic cells (11,12).

TREM-2 also plays a role in suppressing the production of TNF and

IL-6 and TLR signaling in macrophages (13,14).

Moreover, TREM-2 is also involved in the pathology of some

diseases. Related research proved that the defects in TREM-2 may be

a cause of polycystic lipomembranous osteodysplasia with sclerosing

leukeoncephalopathy (PLOSL) (15),

and a rare missense mutation (rs75932628-T) in TREM-2 may confer an

obvious risk of Alzheimer’s disease (16). Recently, TREM-2 is suggested

functioning in human malignancies. Wang et al (17) have indicated that highly expressed

TREM-2 promotes cell proliferation and invasion in glioma cells.

Other studies also suggest that abnormally expressed TREM-2 may be

associated with tumor immune evasion in lung cancer (18). Whereas, the effects of TREM-2 on

RCC are still less known.

In the present study, we revealed the biological

effects of TREM-2 on RCC cells for the first time. We found that

the expression of TREM-2 is abnormally elevated in RCC tumor

tissues. TREM-2 functioned as an oncogene in both RCC cell lines

and tumor-bearing mouse model in vivo. The effect of TREM2

on RCC progression might be related to the regulation of apoptotic

proteins and PTEN-PI3K/Akt pathway. Therefore, TREM-2 may provide a

novel approach to the therapy for RCC.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Renal tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues were

collected from 40 patients with RCC treated at the Huadong

Hospital, Fudan University. The tissues were stored at −80°C until

being used. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

Huadong Hospital, Fudan University. Informed and written consent

were obtained from all patients according to the guidelines of the

ethics committee.

Cell culture

Five RCC cell lines, Caki-1, Caki-2, ACHN, 786-0 and

OS-RC-2 were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection

(ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in RMPI-1640 medium

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), 100 U/ml

penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cell culture was maintained

at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

RNA interference

To knock down the expression of TREM-2 in RCC cells,

siRNA transfection was performed. siRNAs targeting three positions

of human TREM-2 mRNA (NM_001271821.1; siRNA1: 125-147UCUUACUCUUUGUC

ACAGA, siRNA1: 386–408 UUACGCUGCGGAAUCUACA and siRNA3: 591–613

GAGACACGUGAAGGAAGAU) were synthesized. A non-specific scramble

siRNA sequence served as negative control (NC). siRNAs were

transfected into RCC cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following assays

were performed at 48 h post-RNA interference.

CCK-8 assay

To analyze the cell proliferation, Caki-2 and ACHN

cells (5×103) were seeded into 96-well plates and

examined at 0, 24, 48 and 72 h after siRNA transfection using

commercial Cell Counting kit (7seabitech) per the instructions of

the manufacturer. Absorbance excited at 450 nm of reacted cells

were detected to valuate cell growth.

Cell cycle assay

At 48 h after siRNA transfection, Caki-2 and ACHN

cells were collected and fixed by 70% ethanol at −20°C for 2 h.

After being washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cells

were incubated with propidudium iodide (PI; 0.05 mg/ml;

Sigma-Aldrich) in the dark for 30 min. In addition, cell cycle

assay was performed using flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose,

CA, USA) and analyzed using FlowJo cell cycle analysis

software.

Cell apoptosis assay

Caki-2 and ACHN cells were harvested at 48 h

post-RNA interference. Cell apoptosis assay was performed using

Annexin V apoptosis detection kit APC (eBioscience, San Diego, CA,

USA). The cells double stained with Annexin V-fluorescein

isothiocyanate (FITC) and PI were then examined by flow cytometer

(BD Biosciences). At least 10,000 cells were obtained for each

experiment.

Reverse transcription and real-time PCR

(qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from RCC cells and tissue

samples using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Reverse transcription

was performed via cDNA Synthesis kit (Fermentas, Waltham, MA, USA).

qRT-PCR was processed using a standard SYBR-Green PCR kit

(Fermentas). All the procedures were performed according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. The cycle conditions were 10 min at

95°C, 40 cycles of 15 sec at 95°C and 45 sec at 60°C, 15 sec at

95°C, 1 min at 60°C followed by 15 sec at 95°C and 15 sec at 60°C.

GAPDH served as internal control. The primer sequences were the

following: TREM-2 NM_001271821.1): primer F,

5′-TGGCACTCTCACCATTACG-3′ and primer R,

5′-CCTCCCATCATCTTCCTTCAC-3′; Bax (NM_004324.3): primer F,

5′-AGCTGAGCGAGTGTCTCAAG-3′ and primer R,

5′-TGTCCAGCCCATGATGGTTC-3′; Bcl2 (NM_000633.2): primer F,

5′-AGACCGAA GTCCGCAGAACC-3′ and primer R, 5′-GAGACCACACTGC

CCTGTTG-3′; PCNA (NM_002592.2): primer F,

5′-GCCTGACAAATGCTTGCTGAC-3′ and primer R,

5′-TTGAGTGCCTCCAACACCTTC-3′; caspase-3 (NM_004346.3): primer F,

5′-AACTGGACGTGGCATTGAG-3′ and primer R, 5′-ACAAAGCGACTGGATGAACC-3′;

GAPDH (NM_001256799.1): primer F, 5′-CACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTG-3′ and

primer R, 5′-CCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG-3′.

Western blotting

Tissue samples were collected and put into

homogenizer to grind into tissue homogenate. Treated and untreated

RCC cells were harvested and washed twice with PBS. Then, tissue

homogenate and cells were disrupted in a radio-immunoprecipitation

assay lysis buffer. After protein normalization, tissue and cell

samples were separated in SDS-PAGE and transferred to a

nitrocellulose membrane. The blots were then incubated with

appropriate primary and secondary antibodies following blocked with

5% skim milk. Visualization was performed using the enhanced

chemiluminescence (ECL; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The

antibody list was as follows: TREM-2 (1:800, Ab86491; Abcam,

Cambridge, MA, USA), PCNA (1:1,000, #13110; Cell Signaling

Technology Danvers, MA, USA), Bax (1:300, Sc-493; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), Bcl2 (1:300, Sc-492; Santa

Cruz Biotechnology), caspase-3 (1:500, Ab44976; Abcam), PTEN

(1:1,000, #9188; Cell Signaling Technology), PI3K (1:1,000,

Ab189403; Abcam), p-PI3K (1:1,000, Ab182651; Abcam), Akt (1:1,000,

#9272; Cell Signaling Technology), p-Akt (1:1,000, #9271, Cell

Signaling Technology), GAPDH (1:1,500, #5174; Cell Signaling

Technology) and HRP-labeled secondary antibodies (1:1,000, A0208,

A0181, A0216; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnolgy, Haimen,

China).

Nude mouse xenograft model

Animal experiments were approved and performed per

the guidelines of Animal Care and Use Committee of Huadong

Hospital, Fudan University (Shanghai, China). Twelve BALB/c nude

mice aged 4-weeks (SLAC animal) were maintained under specific

pathogen-free conditions using a laminar air-flow rack. All the

mice were fed with sterilized food and autoclaved water. Injection

was performed as previously described (19). Briefly, after one week of

acclimatization, 12 nude mice were divided into two groups, NC

group and siRNA group (n=6/group) randomly, and subcutaneously

injected with ACHN cells transfected with NC-siRNA and TREM-2-siRNA

(2×106) to the armpit of nude mouse, respectively. After

1 week of tumorigenesis, the shortest and longest diameter of the

tumor were measured with calipers every 3 days, and tumor volume

(mm3) was calculated using the following standard

formula: (the shortest diameter)2 × (the longest

diameter) × 0.5. On day 34 post-injection, the mice were sacrificed

by cervical dislocation and the tumors were harvested. The wet

weights of each tumor were examined. During the experimental

procedure, all mice were monitored every 2 days. None of the mice

died prior to the experimental endpoint.

Statistical analysis

At least 3 independent experiments were performed in

every assay. Data analysis used GraphPad Prism software. Data are

expressed as mean (± SD) and analyzed with t-test for multiple

comparisons. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant result.

Results

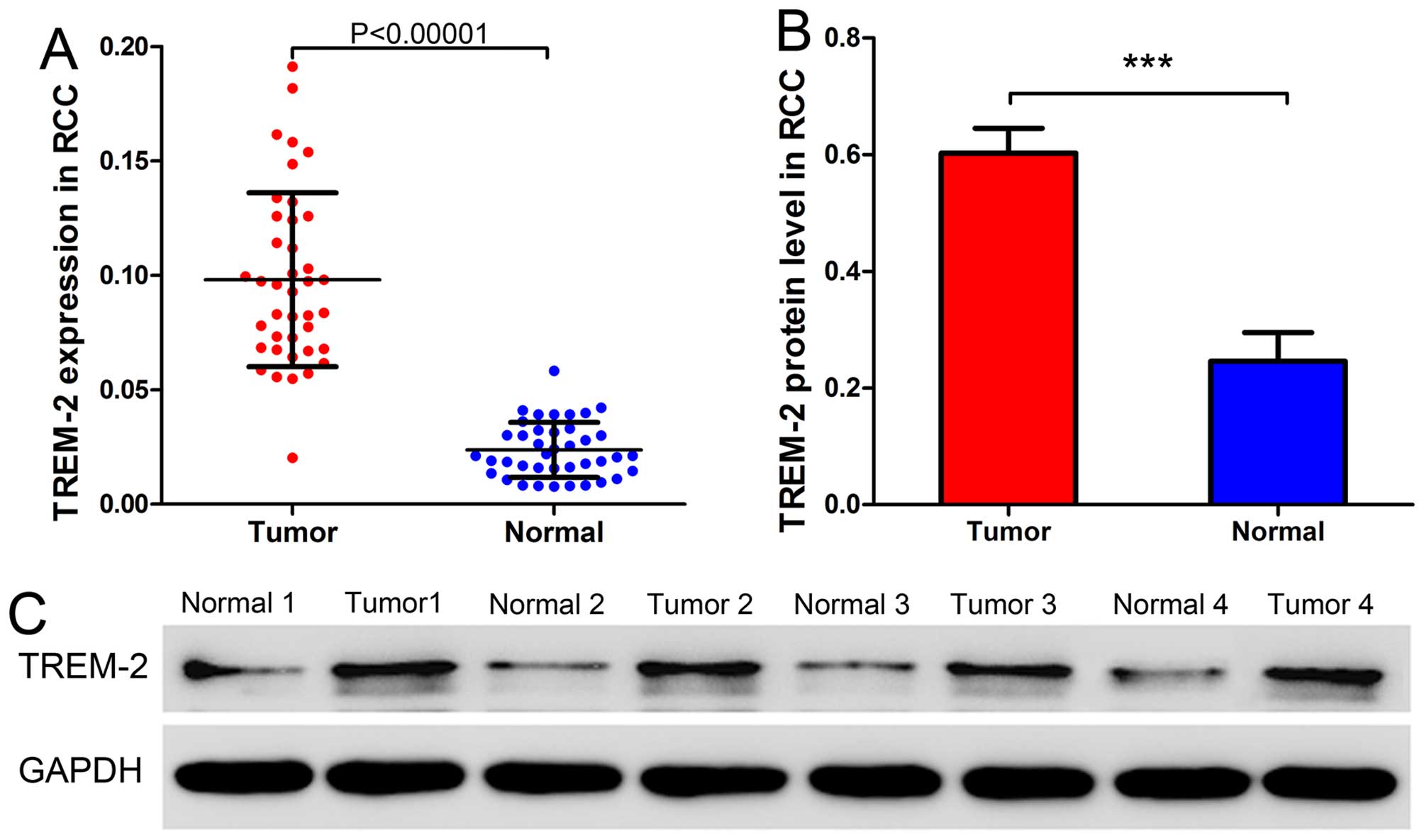

TREM-2 expression is elevated in RCC

tissues

To profile the expression pattern of TREM-2 in RCC,

we analyzed the mRNA and protein expression of TREM-2 in tumor and

adjacent normal tissues from 40 patients with RCC using qRT-PCR and

western blot analysis. As Fig. 1

shows, both mRNA and protein levels of TREM2 were significantly

higher in tumor tissues than adjacent normal tissues. These data

indicated that the expression of TREM-2 was abnormally elevated in

RCC tumor tissues.

TREM-2 knockdown via RNA

interference

We then examined TREM-2 expression level in five RCC

cell lines, including Caki-1, Caki-2, ACHN, 786-0 and OS-RC-2,

using qRT-PCR and western blot analysis. We found that TREM2 was

highly expressed in ACHN and Caki-2 cell lines as comparing to

other three cell lines (Fig. 2A and

B). In addition, we employed these two RCC cell lines to carry

out the following experiments. To further analyzed the biological

functions of TREM-2 in RCC, TREM-2 expression was silenced in ACHN

and Caki-2 cells using RNA interference. The results of qRT-PCR

showed that, the mRNA level of TREM-2 was significantly suppressed

after siRNA transfection. In addition, the siRNA2 (targeting

position 386–408: UUACGCUGCGGAAUCUACA) silenced TREM-2 expression

more effectively as comparing to the other two siRNAs. Thus, siRNA2

was selected as TREM-2-siRNA transfected into cancer cells for the

following assays. The western blot data also confirmed that siRNA2

decreased the protein level of TREM-2 in two RCC cell lines

(Fig. 2C and D).

Depletion of TREM-2 inhibits cell

proliferation in RCC cell lines

We analyzed the cell growth of ACHN and Caki-2 at 0,

24, 48 and 72 h post-RNA interference using CCK-8 assay. As shown

in Fig. 3, obvious decrease of

cell growth was detected in both ACHN and Caki-2 cells at 48 and 72

h after siRNA transfection. Whereas, the cell proliferation was not

affected in the NC group. These data suggested that knockdown of

TREM-2 might suppress cell growth in RCC progression.

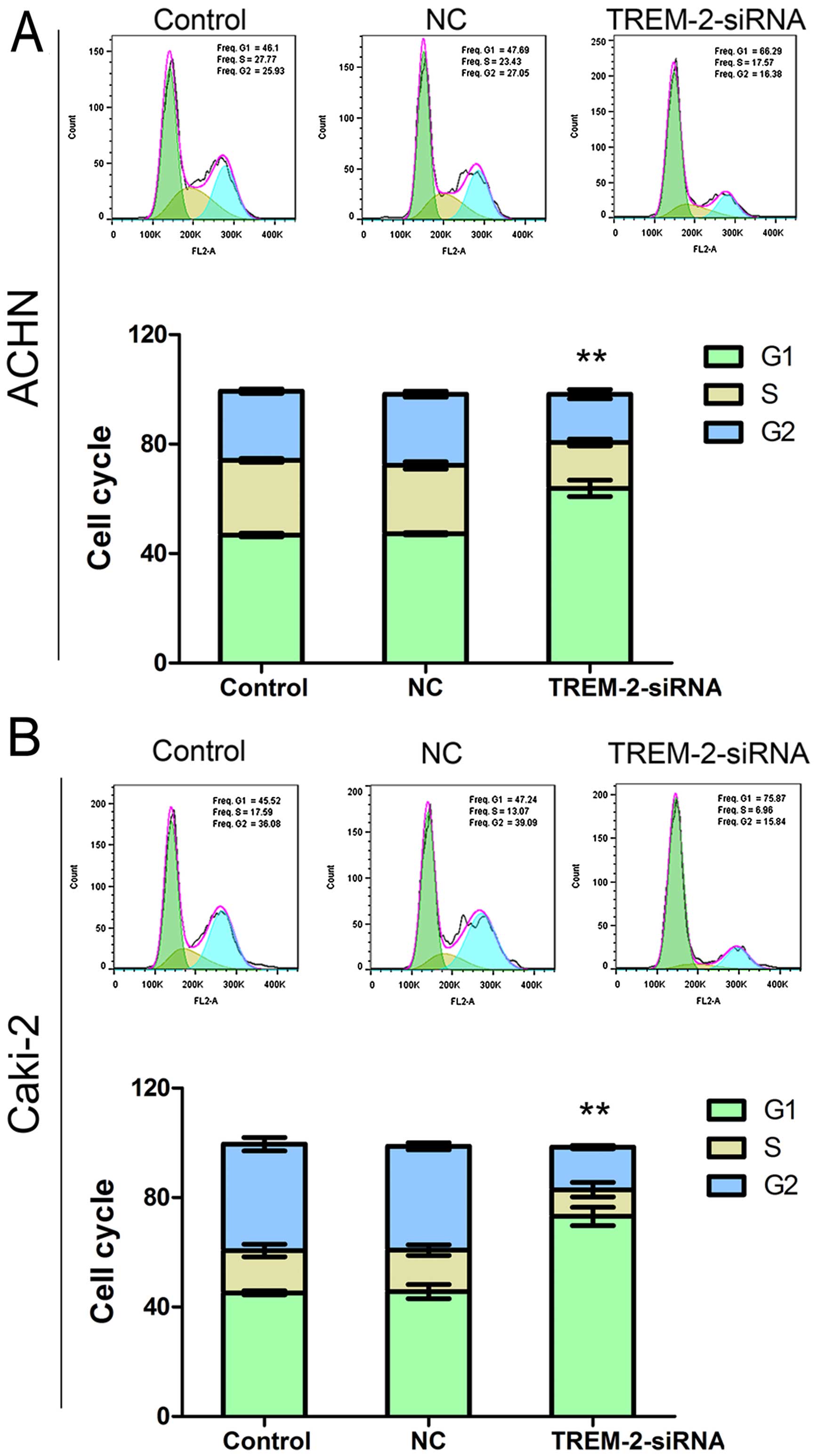

TREM-2 knockdown induces G1 phase arrest

in RCC cell lines

As silencing TREM2 inhibited cell growth in RCC, we

analyzed the effects of TREM-2 on the cell cycle progress in ACHN

and Caki-2 cells sequentially. The RCC cells were stained by PI at

48 h post-RNA interference, and the cell cycle was examined by flow

cytometry. As shown in Fig. 4,

proportion of G1 phase was remarkably increased in siRNA-TREM-2

group than in the NC group, with increased ratios: 35.13 and 60.30%

in ACHN and Caki-2, respectively. These results indicated that,

silencing the expression of TREM-2 might inhibit cell cycle

progress via inducing THE G1 phase arrest.

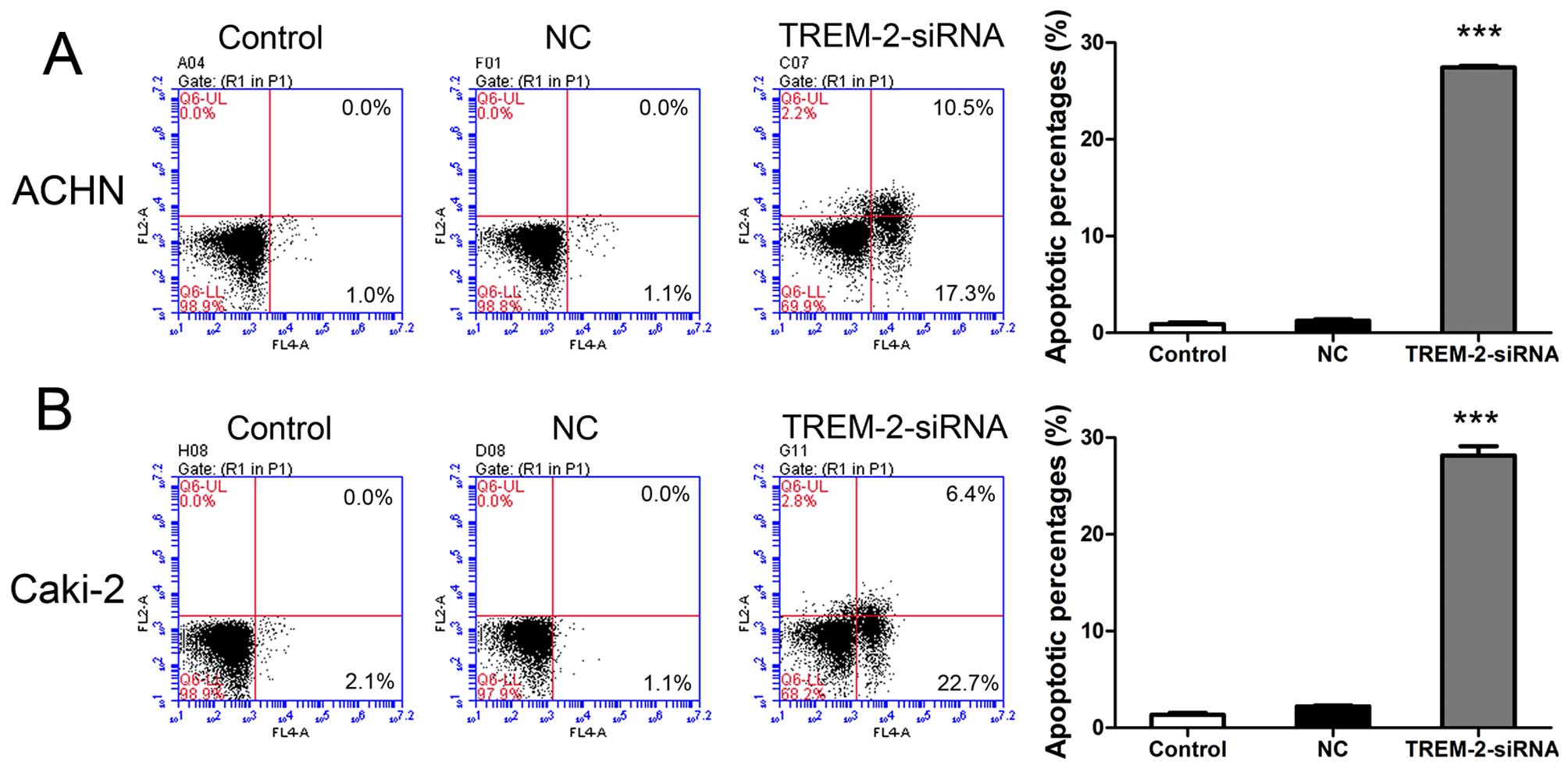

Silencing TREM-2 causes cell apoptosis in

RCC cell lines

We analyzed the effects of TREM-2 on cell apoptosis

in ACHN and Caki-2 cells at 48 h after siRNA transfection. The

cells were double stained by Annexin V-FITC and PI, and examined

using flow cytometry. As illustrated in Fig. 5, ~22-fold increase and 13-fold

increase of cell apoptosis was examined in ACHN and Caki-2 cells of

siRNA groups as comparing to NC groups. The data showed that

knockdown of TREM-2 induced significant cell apoptosis in RCC cell

lines.

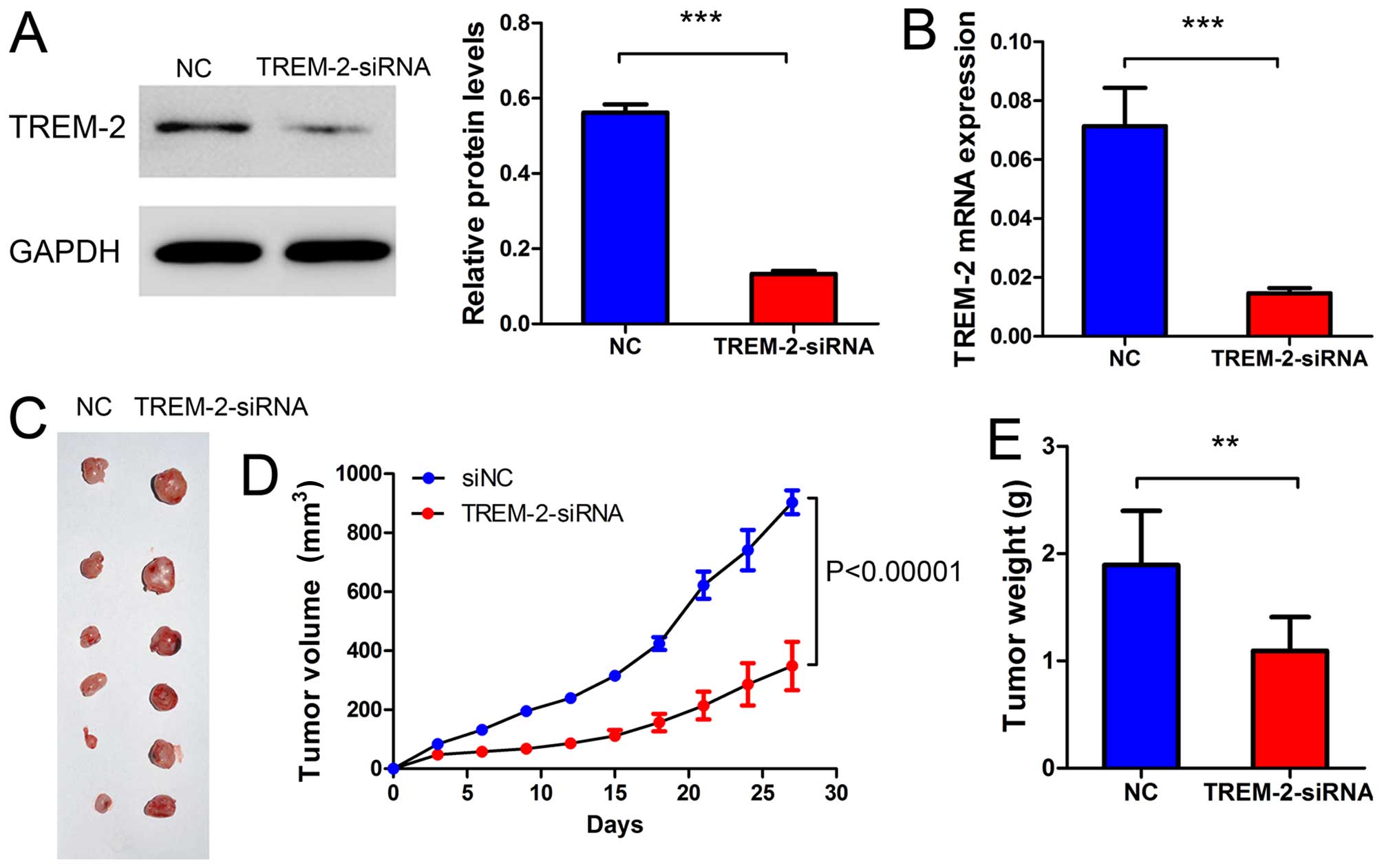

Silencing TREM-2 inhibits xenografted

ACHN tumor development in nude mice

We then examined whether TREM-2 silenced in RCC

cells could inhibit tumor growth in vivo. The ACHN cells

transfected with NC-siRNA or TREM-2-siRNa were subcutaneously

injected into nude mice, respectively. Tumor volumes were measured

for 27 days. The weight of tumors were measured on day 34. As shown

in Fig. 6A–C, the mRNA expression

and protein level of TREM-2 were significantly decreased in

TREM-2-siRNA group compared with NC group. As shown in Fig. 6C–E, both the volume and the weight

of RCC tumors were obviously decreased after TREM-2-siRNA

transfection. These results implicated that TREM-2 knockdown might

inhibit the tumor development of RCC in vivo.

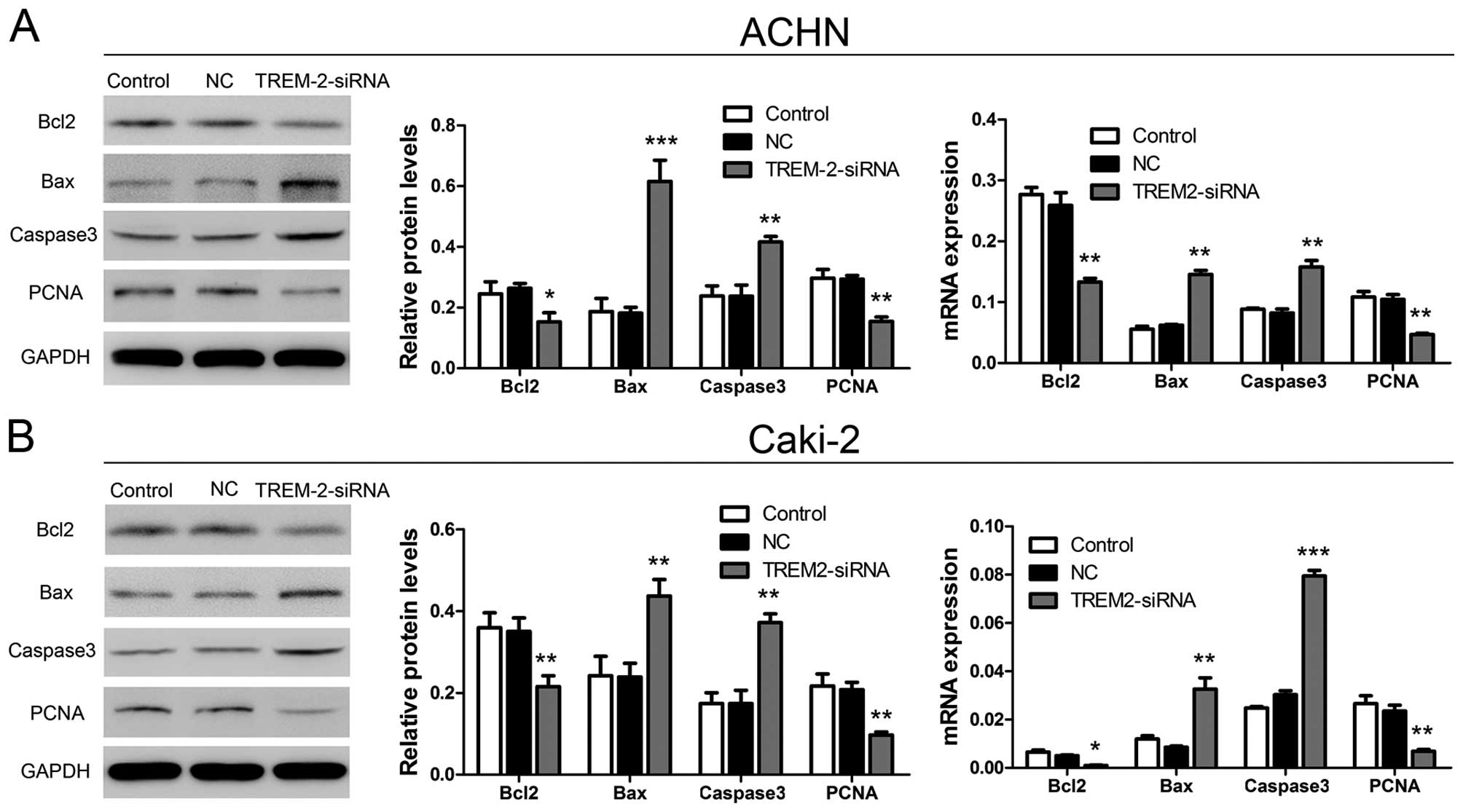

Silencing TREM-2 altered endogenous

expression of proteins related to apoptosis and the cell cycle in

RCC cell lines

As described above, TREM-2 might act as a promoter

in cell proliferation through inducing cell cycle progress and

inhibiting cell apoptosis. We then examined four related protein

levels, including Bcl2, Bax, caspase-3 and PCNA, using qRT-PCR and

western blot analysis at 48 h post-RNA interference. As shown in

Fig. 7, mRNA expression of Bcl2

(decreased ratios: ACHN, 48.55% and Caki-2, 80.47%) and PCNA

(decreased ratios: ACHN, 55.11% and Caki-2, 69.58%) were obviously

decreased after TREM-2 knockdown. Whereas, the mRNA expression of

Bax (increased ratios: ACHN, 134.16% and Caki-2, 172.83%) and

caspase-3 (increase ratios: ACHN, 91.77% and Caki-2, 162.50%) were

significantly increased in siRNA-TREM-2 groups compared to NC

groups. The same results were also examined by western blot

analysis. The protein levels of Bcl-2 and PCNA were reduced, while

the protein levels of Bax and caspase-3 were elevated after siRNA

transfection. The decreased ratios of Bcl2 and PCNA protein levels

were 41.94 and 47.39% in ACHN, 38.54 and 53.59% in Caki-2,

respectively. The increased ratios of Bax and caspase-3 protein

levels were 239.18 and 75.45% in ACHN, and 82.99 and 113.98% in

Caki-2, respectively.

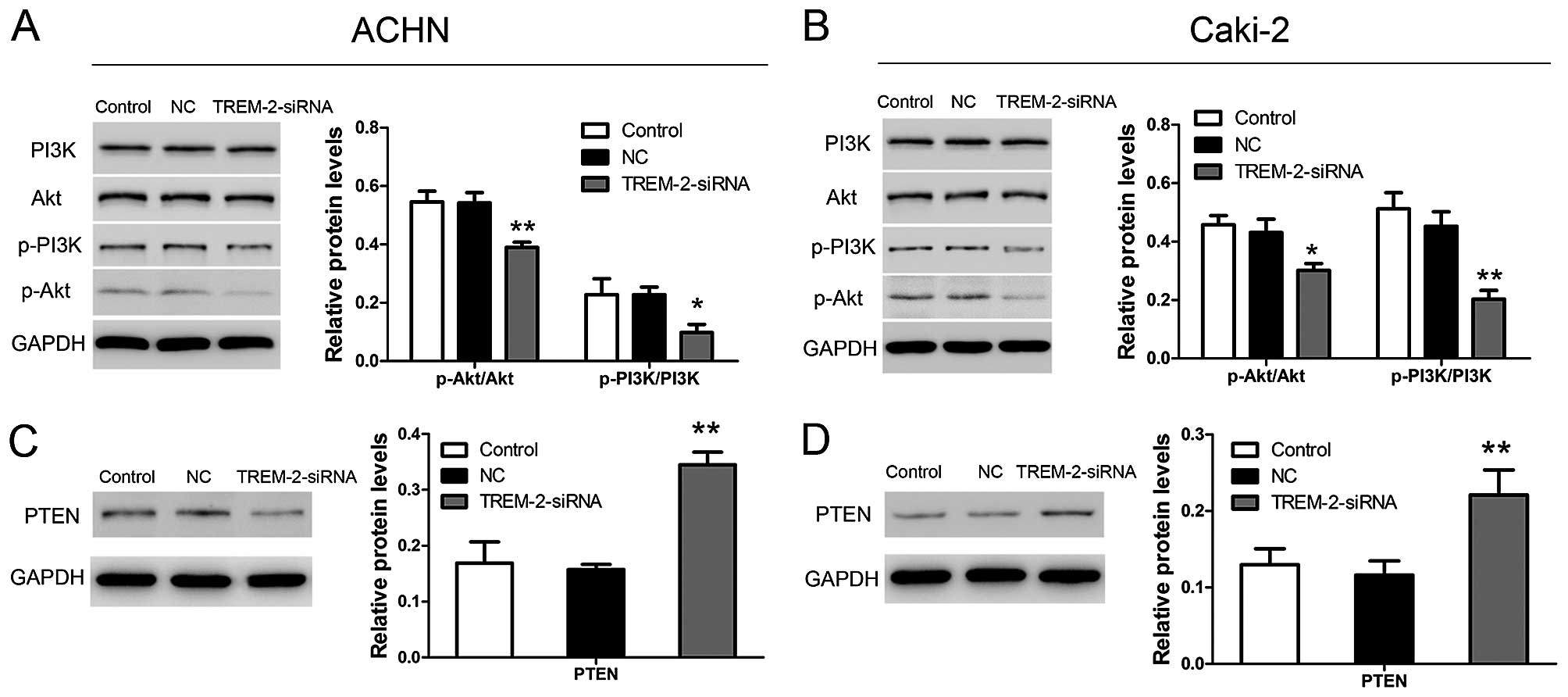

Depletion of TREM-2 inactivates

PTEN-PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in RCC cell lines

To reveal the functional mechanisms of TREM-2 in

cell growth, we analyzed the PTEN-PI3K/Akt signaling pathway using

western blot analysis. As Fig. 8A and

B show, TREM-2 knockdown significantly increased the protein

level of PTEN in ACHN and Caki-2 cells. Depletion of TREM-2

inhibited phoshoprylation of PI3K and Akt in both cell lines

(Fig. 8C and D). These data

suggested that TREM-2 knockdown inhibited the activation of

PI3K/AKT pathway via upregulating the PTEN level in RCC cell

lines.

Discussion

Immunotherapy and targeted therapy have recently

provided new insights into the treatment of RCC. Research on novel

targeting factors still remains urgent. TREM-1, a member of TREM

family, has been suggested to be involved in progression of certain

human malignancies. Liao et al (20) has proved that TREM-1 is related to

the aggressive tumor behavior and has potential value as a

prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma. TREM-1 is

upregulated in macrophages and is associated with cancer recurrence

and poor survival of patients with lung cancer (21,22).

TREM-2 is also suggested to act as an oncogene in glioma (17). Moreover, TREM-2 is proven to

promote tumor immune evasion in lung cancer cells (18). Inspired by the association between

TREMs and human cancers, we sought to reveal the role of TREM-2 in

RCC. We found that the expression of TREM-2 is remarkably

facilitated in tumor tissues compared with the adjacent normal

tissues of patients with RCC. It indicated that elevated TREM-2

might play a role in the RCC progression.

Then, we knocked down the TREM-2 expression in

selected RCC cancer cell lines via RNA interference. In addition,

we examined effects of TREM-2 depletion on cell proliferation,

apoptosis and cell cycle in ACHN and Caki-2. The data showed that

TREM-2 knockdown significantly inhibited cell growth, and induced

cell apoptosis in two RCC cell lines. Similar results were also

found in research by Wang et al (17). In their previous study, silencing

TREM-2 suppressed cell proliferation and promotes cell apoptosis in

glioma cells. In cell cycle assay, we found that depletion of

TREM-2 induced arrest in G1 phase of cell cycle in RCC cells. In

vivo, the data affirmed that knockdown of TREM-2 inhibited

tumorigenesis of RCC cells. The above results illustrated that

TREM-2 might function as an oncogene in RCC development.

To confirm the functional mechanisms of TREM-2 in

RCC cells, we analyzed the protein levels and mRNA expression of

factors related to apoptosis and cell cycle using western blot and

qRT-PCR analysis. We found that in ACHN and Caki-2 cells, both mRNA

expression and protein levels of Bcl2 and PCNA were obviously

decreased post-RNA interference. Whereas, expression of Bax and

caspase-3 were elevated in TREM-2-siRNA groups as comparing to NC

groups in two RCC cell lines. Bcl2 belongs to the antiapoptotic

Bcl2 family, which acts to prevent or delay cell death. Previous

studies indicate that increased expression of Bcl2 in RCC may

decrease the levels of apoptosis and promote resistant to treatment

(23,24). PCNA, a progressivity factor for DNA

polymerase δ, is essential for DNA replication (25,26).

In addition, suppression of PCNA may cause G1 phase arrest in cell

cycle and promote cell death in cancer cells (27). Bax and caspase-3 act as promoters

in cell apoptosis. Especially, activation of caspase-3 plays a

central role in the execution-phase of cell apoptosis (28). Thus, the results of this study

implicated that TREM-2 affects cell growth, apoptosis and cell

cycle through regulating the mRNA expression and intracellular

levels of related proteins.

Finally, we analyzed the effects of TREM-2 on

PTEN-PI3K/Akt pathway. PI3K is a lipid kinase and generated

PI(3,4,5)P3, which is an essential second messenger in

translocation of Akt to plasma membrane. Activated Akt plays a

pivotal role in fundamental cellular functions (29,30).

The activation of PI3K/Akt pathway has been suggested involved in

many kinds of human tumors, such as breast, lung cancer and

leukemia (31–33). PI3K/Akt pathway also plays a key

role in RCC. Activation of PI3K/Akt is associated with the decrease

of the survival rate in RCC (34).

Research has proven that certain anticancer agents, such as Klotho

and β-elemene, inhibit the tumor progression through suppressing

PI3K/Akt signaling in RCC (35–38).

TREM-2 has been proven as an activator in PI3K/Akt signaling

pathway. Elevated TREM-2 can mediate bacterial killing via

activating PI3K/Akt pathway (39,40).

PTEN is identified as a tumor suppressor that is mutated in a large

number of cancers at high frequency (41). PTEN acts as a key negative

regulator in the alternations of PI3K/Akt through decreasing the

intracellular level of PI(3,4,5)P3 in cells (42). In addition, the disturbed

expression and function of PTEN have been examined in both human

cancer cell lines and human malignancies (43–45).

Research has implicated that inhibition of PTEN may cause permanent

activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway (46). In the present study, we found that

TREM-2 knockdown significantly inactivated the PI3K/Akt pathway by

downregulating the intracellular protein levels of p-PI3K and

p-Akt, and increased the intracellular protein level of PTEN in two

RCC cell lines. Therefore, the data suggested that TREM-2 might act

as a regulator of PI3K/Akt through altering the PTEN level in

RCC.

In conclusion, this study first revealed the role of

TREM-2 in RCC progression. We found that TREM-2 is abnormally

elevated in RCC tissues. Knockdown of TREM-2 obviously inhibited

cell proliferation, induced cell apoptosis and G1 phase arrest in

RCC cells. The in vivo experiments also confirmed that

depletion of TREM-2 suppressed the tumor development of RCC.

Moreover, the oncogene functional effects of TREM-2 might be caused

by its regulation of related proteins and PTEN-PI3K/Akt pathway.

Therefore, TREM-2 may be considered as a potential therapeutic

target in the treatment of RCC.

References

|

1

|

Yi Z, Fu Y, Zhao S, Zhang X and Ma C:

Differential expression of miRNA patterns in renal cell carcinoma

and nontumorous tissues. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 136:855–862.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Rini BI, Campbell SC and Escudier B: Renal

cell carcinoma. Lancet. 373:1119–1132. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C,

O’Corragain OA, Edmonds PJ, Ungprasert P, Kittanamongkolchai W and

Erickson SB: The risk of kidney cancer in patients with kidney

stones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. QJM. 108:205–212.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, Jacqmin

D, Lee JE, Weikert S and Kiemeney LA: The epidemiology of renal

cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 60:615–621. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Singer EA, Gupta GN, Marchalik D and

Srinivasan R: Evolving therapeutic targets in renal cell carcinoma.

Curr Opin Oncol. 25:273–280. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Allcock RJ, Barrow AD, Forbes S, Beck S

and Trowsdale J: The human TREM gene cluster at 6p21.1 encodes both

activating and inhibitory single IgV domain receptors and includes

NKp44. Eur J Immunol. 33:567–577. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Klesney-Tait J, Turnbull IR and Colonna M:

The TREM receptor family and signal integration. Nat Immunol.

7:1266–1273. 2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Whittaker GC, Orr SJ, Quigley L, Hughes L,

Francischetti IM, Zhang W and McVicar DW: The linker for activation

of B cells (LAB)/non-T cell activation linker (NTAL) regulates

triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM)-2 signaling

and macrophage inflammatory responses independently of the linker

for activation of T cells. J Biol Chem. 285:2976–2985. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

9

|

Paradowska-Gorycka A and Jurkowska M:

Structure, expression pattern and biological activity of molecular

complex TREM-2/DAP12. Hum Immunol. 74:730–737. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Filbert EA: Investigations of mechanisms

involved in LPS-stimulated osteoclastogenesis. University of

Connecticut, School of Dental Medicine; SoDM Masters Theses, Paper

155. 2007

|

|

11

|

Sharif O and Knapp S: From expression to

signaling: Roles of TREM-1 and TREM-2 in innate immunity and

bacterial infection. Immunobiology. 213:701–713. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Tomasello E, Desmoulins P-O, Chemin K,

Guia S, Cremer H, Ortaldo J, Love P, Kaiserlian D and Vivier E:

Combined natural killer cell and dendritic cell functional

deficiency in KARAP/DAP12 loss-of-function mutant mice. Immunity.

13:355–364. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Helming L, Tomasello E, Kyriakides TR,

Martinez FO, Takai T, Gordon S and Vivier E: Essential role of

DAP12 signaling in macrophage programming into a fusion-competent

state. Sci Signal. 1:ra112008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Turnbull IR, Gilfillan S, Cella M, Aoshi

T, Miller M, Piccio L, Hernandez M and Colonna M: Cutting edge:

TREM-2 attenuates macrophage activation. J Immunol. 177:3520–3524.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Paloneva J, Manninen T, Christman G,

Hovanes K, Mandelin J, Adolfsson R, Bianchin M, Bird T, Miranda R,

Salmaggi A, et al: Mutations in two genes encoding different

subunits of a receptor signaling complex result in an identical

disease phenotype. Am J Hum Genet. 71:656–662. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J,

Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe

JS, Younkin S, et al; Alzheimer Genetic Analysis Group. TREM2

variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 368:117–127. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Wang XQ, Tao BB, Li B, Wang XH, Zhang WC,

Wan L, Hua XM and Li ST: Overexpression of TREM2 enhances glioma

cell proliferation and invasion: A therapeutic target in human

glioma. Oncotarget. 7:2354–2366. 2016.

|

|

18

|

Yao Y, Li H, Wang Y and Zhou J: Triggering

receptor expressed on myeloid cells-2 (TREM-2) elicited by lung

cancer cells to facilitate tumor immune evasion. J Clin Oncol.

31(Suppl): 220542013.

|

|

19

|

Chen Y, Guo Y, Yang H, Shi G, Xu G, Shi J,

Yin N and Chen D: TRIM66 overexpresssion contributes to

osteosarcoma carcinogenesis and indicates poor survival outcome.

Oncotarget. 6:23708–23719. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liao R, Sun TW, Yi Y, Wu H, Li YW, Wang

JX, Zhou J, Shi YH, Cheng YF, Qiu SJ, et al: Expression of TREM-1

in hepatic stellate cells and prognostic value in hepatitis

B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 103:984–992. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ho CC, Liao WY, Wang CY, Lu YH, Huang HY,

Chen HY, Chan WK, Chen HW and Yang PC: TREM-1 expression in

tumor-associated macrophages and clinical outcome in lung cancer.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 177:763–770. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Yuan Z, Mehta HJ, Mohammed K, Nasreen N,

Roman R, Brantly M and Sadikot RT: TREM-1 is induced in tumor

associated macrophages by cyclo-oxygenase pathway in human

non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 9:e942412014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Gobé G, Rubin M, Williams G, Sawczuk I and

Buttyan R: Apoptosis and expression of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, and Bax in

renal cell carcinomas. Cancer Invest. 20:324–332. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sejima T and Miyagawa I: Expression of

bcl-2, p53 oncoprotein, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen in

renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 35:242–248. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fisher PA, Moutsiakis DL, McConnell M,

Miller H and Mozzherin DJ: A single amino acid change (E85K) in

human PCNA that leads, relative to wild type, to enhanced DNA

synthesis by DNA polymerase δ past nucleotide base lesions (TLS) as

well as on unmodified templates. Biochemistry. 43:15915–15921.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhang P, Sun Y, Hsu H, Zhang L, Zhang Y

and Lee MY: The interdomain connector loop of human PCNA is

involved in a direct interaction with human polymerase δ. J Biol

Chem. 273:713–719. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Pleschke JM, Kleczkowska HE, Strohm M and

Althaus FR: Poly(ADP-ribose) binds to specific domains in DNA

damage checkpoint proteins. J Biol Chem. 275:40974–40980. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Cohen GM: Caspases: The executioners of

apoptosis. Biochem J. 326:1–16. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Datta SR, Brunet A and Greenberg ME:

Cellular survival: A play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 13:2905–2927.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Vivanco I and Sawyers CL: The

phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev

Cancer. 2:489–501. 2002. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Fry MJ: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

signalling in breast cancer: How big a role might it play? Breast

Cancer Res. 3:304–312. 2001. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Lin X, Böhle AS, Dohrmann P, Leuschner I,

Schulz A, Kremer B and Fändrich F: Overexpression of

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in human lung cancer. Langenbecks

Arch Surg. 386:293–301. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Martínez-Lorenzo MJ, Anel A, Monleón I,

Sierra JJ, Piñeiro A, Naval J and Alava MA: Tyrosine

phosphorylation of the p85 subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

correlates with high proliferation rates in sublines derived from

the Jurkat leukemia. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 32:435–445. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Merseburger AS, Hennenlotter J, Kuehs U,

Simon P, Kruck S, Koch E, Stenzl A and Kuczyk MA: Activation of

PI3K is associated with reduced survival in renal cell carcinoma.

Urol Int. 80:372–377. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Zhu Y, Xu L, Zhang J, Xu W, Liu Y, Yin H,

Lv T, An H, Liu L, He H, et al: Klotho suppresses tumor progression

via inhibiting PI3K/Akt/GSK3β/Snail signaling in renal cell

carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 104:663–671. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Zhan YH, Liu J, Qu XJ, Hou KZ, Wang KF,

Liu YP and Wu B: β-Elemene induces apoptosis in human renal-cell

carcinoma 786–0 cells through inhibition of MAPK/ERK and

PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling pathways. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev.

13:2739–2744. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Li H, Zeng J and Shen K: PI3K/AKT/mTOR

signaling pathway as a therapeutic target for ovarian cancer. Arch

Gynecol Obstet. 290:1067–1078. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Roy SK, Srivastava RK and Shankar S:

Inhibition of PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways causes activation of

FOXO transcription factor, leading to cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis in pancreatic cancer. J Mol Signal. 5:102010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Sun M, Zhu M, Chen K, Nie X, Deng Q,

Hazlett LD, Wu Y, Li M, Wu M and Huang X: TREM-2 promotes host

resistance against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection by suppressing

corneal inflammation via a PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 54:3451–3462. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Zhu M, Li D, Wu Y, Huang X and Wu M:

TREM-2 promotes macrophage-mediated eradication of Pseudomonas

aeruginosa via a PI3K/Akt pathway. Scand J Immunol. 79:187–196.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Myers MP and Tonks NK: PTEN: Sometimes

taking it off can be better than putting it on. Am J Hum Genet.

61:1234–1238. 1997. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Maehama T and Dixon JE: The tumor

suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second

messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem.

273:13375–13378. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Eng C: PTEN: One gene, many syndromes. Hum

Mutat. 22:183–198. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Muñoz J, Lázcoz P, Inda MM, Nistal M,

Pestaña A, Encío IJ and Castresana JS: Homozygous deletion and

expression of PTEN and DMBT1 in human primary neuroblastoma and

cell lines. Int J Cancer. 109:673–679. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Nassif NT, Lobo GP, Wu X, Henderson CJ,

Morrison CD, Eng C, Jalaludin B and Segelov E: PTEN mutations are

common in sporadic microsatellite stable colorectal cancer.

Oncogene. 23:617–628. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Osaki M, Oshimura M and Ito H: PI3K-Akt

pathway: Its functions and alterations in human cancer. Apoptosis.

9:667–676. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|