Introduction

Malignant melanoma is the most dangerous type of

skin cancer, accounting for more than 75% of deaths related to skin

cancer. Patients with advanced melanoma with dissemination to

distant sites and visceral organs have a very poor prognosis, with

a median survival time of 6 months and a 5-year survival rate of

less than 5% (1). Currently, very

limited treatment options are available for metastatic melanoma.

Although multiple clinical trials have been initiated for novel

agents to treat melanoma, these have met with limited success, thus

highlighting the need for the development of new drugs and

identification of novel therapeutic targets for effective cancer

therapy.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) in eukaryotic cells

is required for several critical functions, including lipid and

cholesterol biosynthesis, maintenance of calcium homeostasis, and

transport of nascent proteins to subcellular organelles (2). Cellular stress conditions, such as

aberrant calcium signaling and accumulation of misfolded proteins

could lead to ER stress and activation of a counteractive reaction

called the ER stress response or unfolded protein response, which

serves to restore ER functionality and homeostasis (3,4).

However, prolonged induction of acute ER stress can lead to cell

death (5–9). Thus, while moderate ER stress

triggers cell survival signaling, severe stress may potentiate cell

death.

ER stress is regulated by two critical proteins,

glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) and CCAAT/enhancer binding

protein homologous protein (CHOP) (10,11).

GRP78 is a key member of the HSP70 protein family that functions as

an ER chaperone involved in protein folding and assembly and

ER-mediated stress signaling (12). Overexpression of GRP78 has been

observed to cause aggressive tumor behavior and promote

angiogenesis in various solid tumors (13–17).

In melanoma, enhanced activation of GRP78 has been associated with

poor patient survival and increased disease progression through

downregulation of apoptosis and activation of unfolded protein

response mechanisms (18). De

Ridder et al found a link between humoral response to GRP78

and cancer progression in a murine model of melanoma (19). Studies have also demonstrated a

distinct role of GRP78 in drug resistance; GRP78 induced

doxorubicin resistance in dormant squamous carcinoma cells through

inhibition of BAX activation (20). Of note, GRP78 is expressed only on

the surface of cancer cells and not on the surface of normal cells,

making it an important target for therapeutic intervention

(17).

In contrast, prolonged expression of CHOP results in

cytotoxicity (21). Incremental

CHOP levels have been associated with increased apoptosis and

reduced tumor growth (22,23). Furthermore, numerous studies

indicate that knockdown of CHOP leads to significantly decreased

drug effects in cancer cells, confirming that CHOP plays a critical

role in mediating ER stress-induced cytotoxicity (24–26).

Thus, ER stress can be described as a double-edged sword: moderate

or chronic levels of ER stress can activate pro-survival cellular

signaling pathways through GRP78, whereas severe or acute levels of

ER stress can lead to cell death via activation of CHOP.

Autophagy is a self-digestive process that

facilitates lysosomal degradation of cytoplasmic proteins and

organelles as a means of maintaining cellular homeostasis and

adapting to different forms of stress (27,28).

Autophagy is primarily a mechanism of cell survival; however,

prolonged exposure of cells to deprivation conditions such as DNA

damage, oxidative stress, and starvation can lead to induction of

excessive autophagy, causing depletion of cellular organelles and

self-destruction (29,30). Thus, similarly to ER stress,

autophagy also plays a dual role in cancer. For instance, tumors

with activating mutations in Ras have been shown to employ

autophagy for survival (31).

Noteworthy, although nuclear p53 transactivates autophagy inducers

such as DRAM1 and sestrin2, cytoplasmic p53 inhibits autophagy

(32,33). Gene knockout of the autophagy

regulatory protein, Beclin-1, was found to increase tumor incidence

in mice with lymphoma and lung cancer (34,35).

Similarly, death-associated protein kinase (DAPK-1), which has

cancer metastasis suppressive properties, is activated following an

accumulation of unfolded proteins in cells, leading to ER stress

and initiation of autophagy through phosphorylation of Beclin-1

(36–38). Unfolded protein response, which is

triggered as an ER stress response, potentially induces autophagy;

binding of GRP78 to misfolded proteins leads to the release of the

3 ER membrane-associated proteins, PKR-like eIF2α kinase (PERK),

activation transcription factor-6 (ATF-6), and inositol-requiring

enzyme-1 (IRE-1) (39,40). Of note, although both PERK and

ATF-6 promote autophagy, IRE-1 attenuates the autophagic response

in cells. Furthermore, multiple recent studies have indicated that

ER stress can magnify autophagy and vice versa (41–44).

Hence, both ER stress and autophagy constitute valid therapeutic

targets, and inhibition of either or both of these processes could

lead to improved therapeutic outcomes.

25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N, an analogue of cephalostatin 1

(Fig. 1), is a potent anticancer

agent with 50% inhibitory concentrations in the subnanomolar range

(45). Testing of this compound in

the NCI-60 cell line panel indicated that the compound is highly

effective against leukemia, melanoma lung, breast, renal, colon,

and prostate cancer cells (46,47).

Recent work by Kanduluru et al outlined the synthesis of

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N (45). However, very little is known about

the mechanism of action of this novel inhibitor in cancer cells. In

this study, we aimed to delineate the mechanism of antitumor

activity of 25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N

in melanoma cells. We found that 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N triggered ER stress and autophagic cell

death in melanoma cells and inhibited tumor growth in mouse

xenografts. Importantly, 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N was therapeutically selective toward

melanoma cells, whereas, normal melanocytes were resistant to it.

These findings indicate that further study is warranted of

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N as a

potential therapeutic agent for melanoma.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and reagents

A375 melanoma cells were purchased from American

Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). WM35 cells were

purchased from the characterized cell line core at The University

of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX, USA). WM35 PKB

cells, which stably overexpress Akt, were a kind gift from Dr Jack

Arbiser (Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA, USA).

Normal human epidermal melanocytes were purchased from PromoCell

(Heidelberg, Germany). A375 and WM35/WM35 PKB cells maintained in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and RPMI-1640 medium

supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum were

grown in a cell culture incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2 in

humidified air. Normal melanocytes were grown in M254CF medium

supplemented with human melanocyte growth supplement-2 (Life

Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA) in a cell culture incubator at

37°C with 5% CO2. The compound 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N was synthesized and

provided by the research group of Dr Philip L. Fuchs, Purdue

University (West Lafayette, IN, USA). 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N was first dissolved in dimethyl

sulfoxide and then further diluted in media to a final

concentration of 0.1%. Rhodamine 123, a fluorescent dye for the

detection of mitochondrial membrane potential, was purchased from

Life Technologies.

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetra-zolium bromide (MTT)

and propidium iodide were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis,

MO, USA), and an Annexin V-FITC kit was purchased from BD

Pharmingen (San Jose, CA, USA). Antibodies were obtained from the

following commercial sources: β-actin from Calbiochem (San Diego,

CA, USA), GRP78 (BiP) and p62 from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa

Cruz, CA, USA), LC3B from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, CO, USA),

and CHOP from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA).

Cytotoxicity assays

The antiproliferative effect of 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N was determined by

performing the MTT assay. A375 and WM35 cells were plated in

triplicate in a 96-well plate (2,000 cells per well). After

overnight incubation, the cells were treated with log-scale serial

diluted concentrations of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N and incubated at 37°C for 72 h, followed

by treatment with 50 µl of MTT reagent for 4 h. The cell

media was aspirated and the formazan precipitates were dissolved in

dimethyl sulfoxide. Absorbance at 570 nm was measured in a

Multiskan MK3 microplate-reader (Thermo Labsystem, Franklin, MA,

USA). The 50% inhibitory concentration values were then computed

using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA,

USA).

Cell apoptosis and necrosis were measured

using flow cytometry

Briefly, cells were harvested, washed in ice-cold

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and suspended in Annexin V binding

buffer. Cells were then stained with Annexin V-FITC for 15 min,

washed, and stained with propidium iodide. Cell death was

quantified using a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur flow cytometer

(Mountain View, CA, USA) and the results were analyzed using FlowJo

(TreeStar, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

Colony formation assay

To assess the effect of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N on the colony formation capacity of

cells, we treated A375 and WM35 cells (5,000 cells per well) with

serial diluted concentrations of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N for 2 weeks. At the end of this period,

the cells were fixed in methanol/acetic acid (10:1) fixation

solution and stained with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich). The stained cells

were photographed and counted.

Mitochondrial membrane potential

assay

Melanoma and normal melanocyte cells were stained

with 0.5 µM Rhodamine 123 during the last hour of treatment

with 25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N. The

cells were then harvested, washed, and suspended in PBS. The

mitochondrial membrane potential of the cells was measured using a

FACSCalibur flow cytometer and subsequent data analysis was

performed using FlowJo software.

Immunoblotting

Cellular protein extracts were separated using

standard SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a nitro cellulose membrane.

The membrane was probed for the indicated primary antibodies,

followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

secondary antibodies. The signal was developed using a

supersignal-enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Scientific).

In vivo antitumor activity assay

All animal experiments were performed according to

Institutional Animal Care and Use protocol at MD Anderson Cancer

Center. Ten athymic nude mice were each subcutaneously inoculated

with 2×106 WM35 PKB cells. The mice were divided into 2

groups (5 mice each); mice in the treatment group were injected

intraperitoneally with 2 mg/ kg 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N, and mice in the control group were

injected with an equal volume of PBS. The mice were monitored

routinely for tumor growth and body weight. Moribund animals were

sacrificed according to Institutional Animal Care and Use protocol,

and the time of death was recorded.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using

GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data are

represented as means ± standard error of the mean. 95% confidence

intervals were used to determine statistical significance.

Results

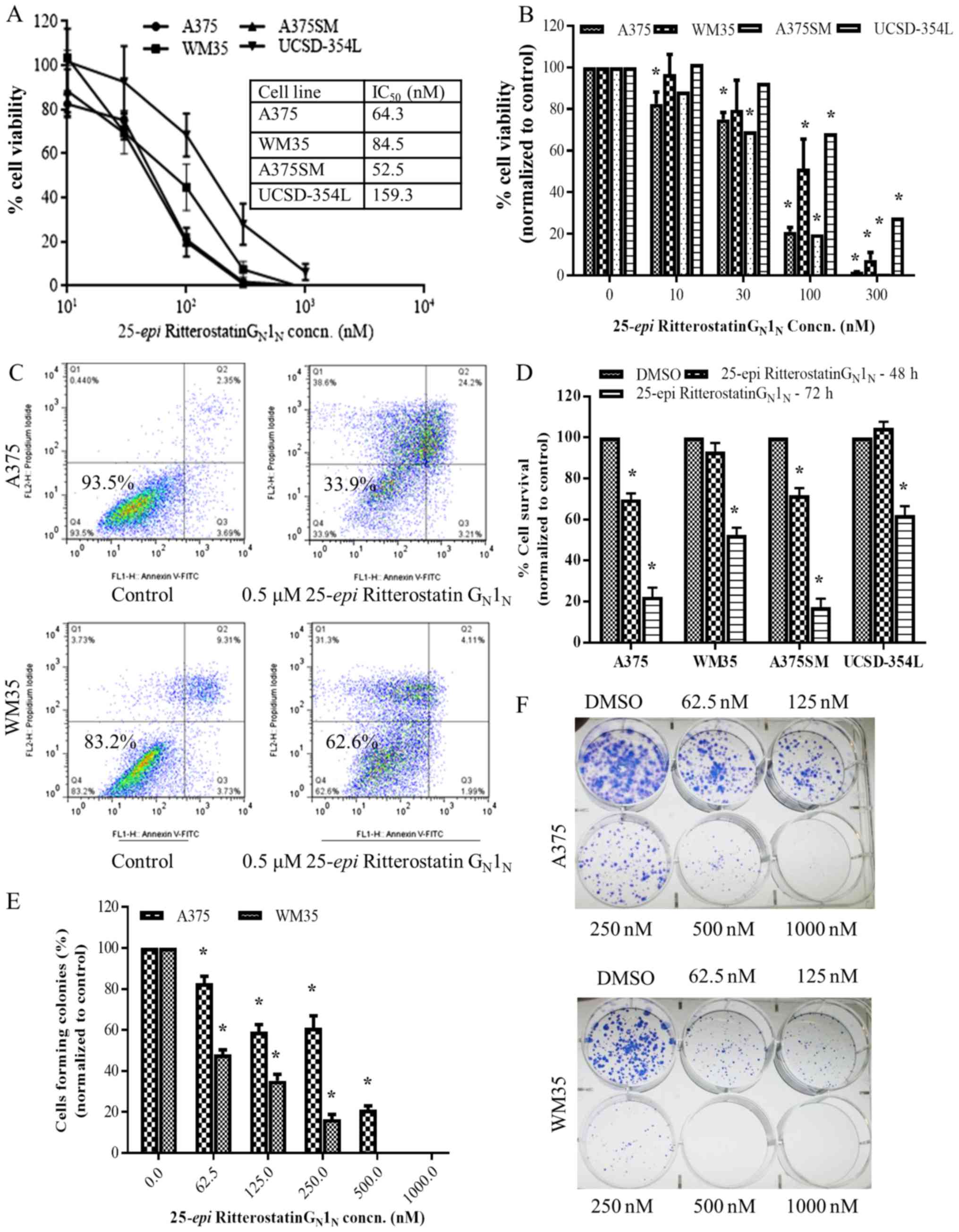

25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N inhibits growth and viability of

melanoma cells at nanomolar concentrations

The effect of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N on the viability of A375 and other

melanoma cells was determined by performing the MTT assay. Exposure

to log-scale serial diluted concentrations (0–100 nM) of

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N for 72 h

resulted in concentration- and time-dependent cell death in

melanoma cells, with an average 50% inhibitory concentration of

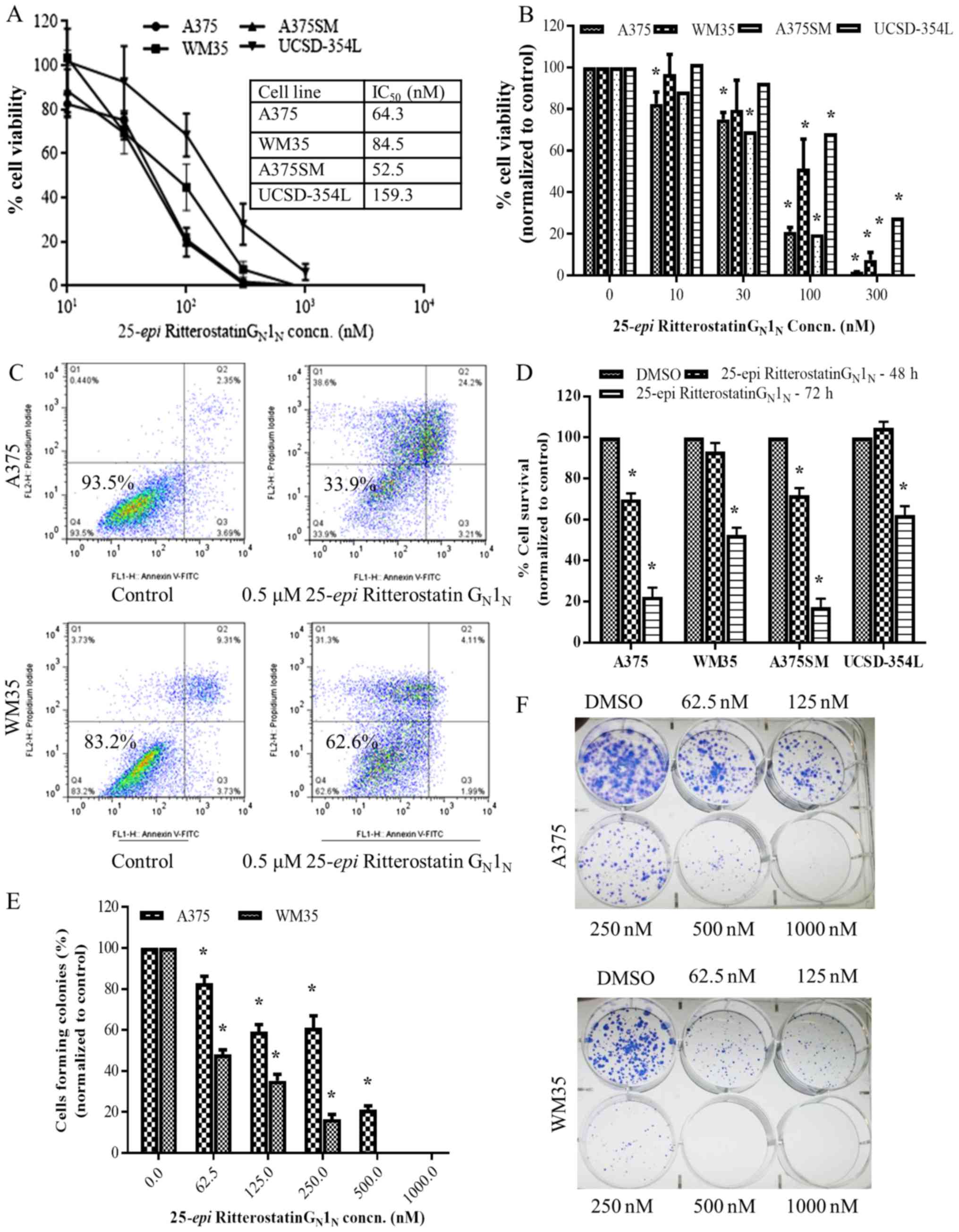

90.2 nM across four melanoma cell lines (Fig 2A and B).

| Figure 225-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N is cytotoxic at nanomolar concentrations

in melanoma cells. (A and B) MTT assay results showing A375, WM35,

A375SM, and UCSD-354L melanoma cell viability after treatment with

various concentrations of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N for 72 h. IC50, 50%

inhibitory concentration. (C) Percentage of viable WM35 and A375

cells after treatment with 0.5 µM 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N for 72 h, determined

according to Annexin V-FITC/propidium iodide staining and

subsequent flow cytometry analysis. (D) The bar graphs represent

the percentage of viable A375, WM35, A375SM, and UCSD-354L cells

(mean ± standard error) after treatment with 0.5 µM

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N for 48 and

72 h, for 3 independent measurements, according to Annexin

V-FITC/propidium iodide staining analysis. (E and F) Giemsa

staining for colony formation assessment in A375 and WM35 cells

treated with varying concentrations of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N [or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) only] for

14 days. The bar graphs represent the mean (± standard error of the

mean) of three independent measurements. *p<0.05. |

To measure melanoma cell death after treatment with

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N, we

performed Annexin V/propidium iodide staining in WM35, A375,

UCSD354L, and A375SM cells treated with 0.5 µM 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N (Fig. 2C and D). Results of a follow-up

colony-formation assay showed that 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N suppressed colony formation at

concentrations as low as 62.5 nM in melanoma cells (Fig. 2E and F). A375 cells, which were

relatively more sensitive than WM35 cells to 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N according to the MTT cell

viability assay, were comparatively resistant to 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N in the colony-formation

assay. A concentration dependent decrease in colony formation was

observed in melanoma cells at higher concentrations of

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N. These

results demonstrate that 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N is cytotoxic and inhibits tumor growth

in melanoma cells at nanomolar concentrations.

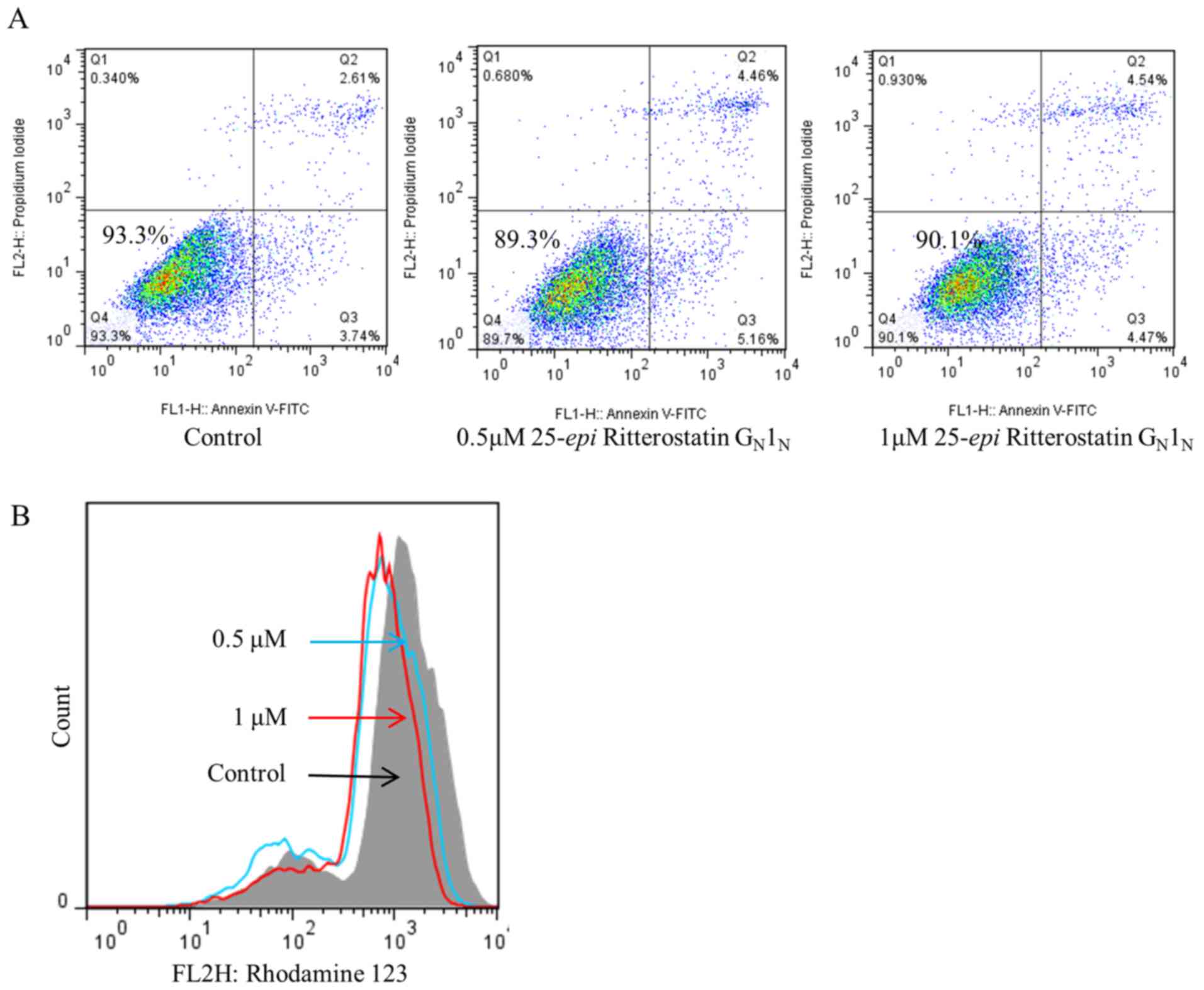

Cell death caused by 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N is mediated through autophagy

Further investigation of the mechanisms of action of

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N revealed

that cell death occurred as a result of autophagy. A massive

collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential was observed in

melanoma cells treated with 0.5 and 1 µM 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N compared with untreated

cells (Fig. 3A and B). This

decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential was

time-dependent.

To confirm the role of autophagy in mediating

cytotoxicity, we treated A375 cells with 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N in combination with

chloroquine. Chloroquine is a lysosomotrophic agent known to

promote rapid cell death in autophagic cells by inhibiting lysosome

acidification and degradation of autophagosomes, thus sensitizing

the cells to drug action (48,49).

For this experiment, 1 µM 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N was added to A375 cells pretreated with

10 µM chloroquine for 1 h. A significant increase in cell

death was observed in cells pretreated with chloroquine compared

with cells treated with 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N alone (Fig.

3C and D). Furthermore, cell death was rapid in the cells

pretreated with chloroquine; only 29.3% of cells were viable at 24

h after treatment (Fig. 3C).

However, the viability of A375 cells treated with 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N or chloroquine alone was

very similar to that of the control cells. Western blot analysis of

A375 cells treated with 0.5 µM 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N showed time-dependent lipidation of the

microtubule-associated autophagy marker protein, LC3B and increased

turnover of its phosphotidyl-ethanolamine-conjugated,

faster-migrating isoform, LC3B-II (Fig. 3E). The presence of LC3 protein in

autophagosomes and increased conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II has been

regarded as a key indicator of autophagy (50,51).

Taken together, the increased expression of LC3B-II,

collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential, and rapid apoptotic

cell death after pretreatment with chloroquine indicate that

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N exerts its

antitumor effect in melanoma through induction of autophagy.

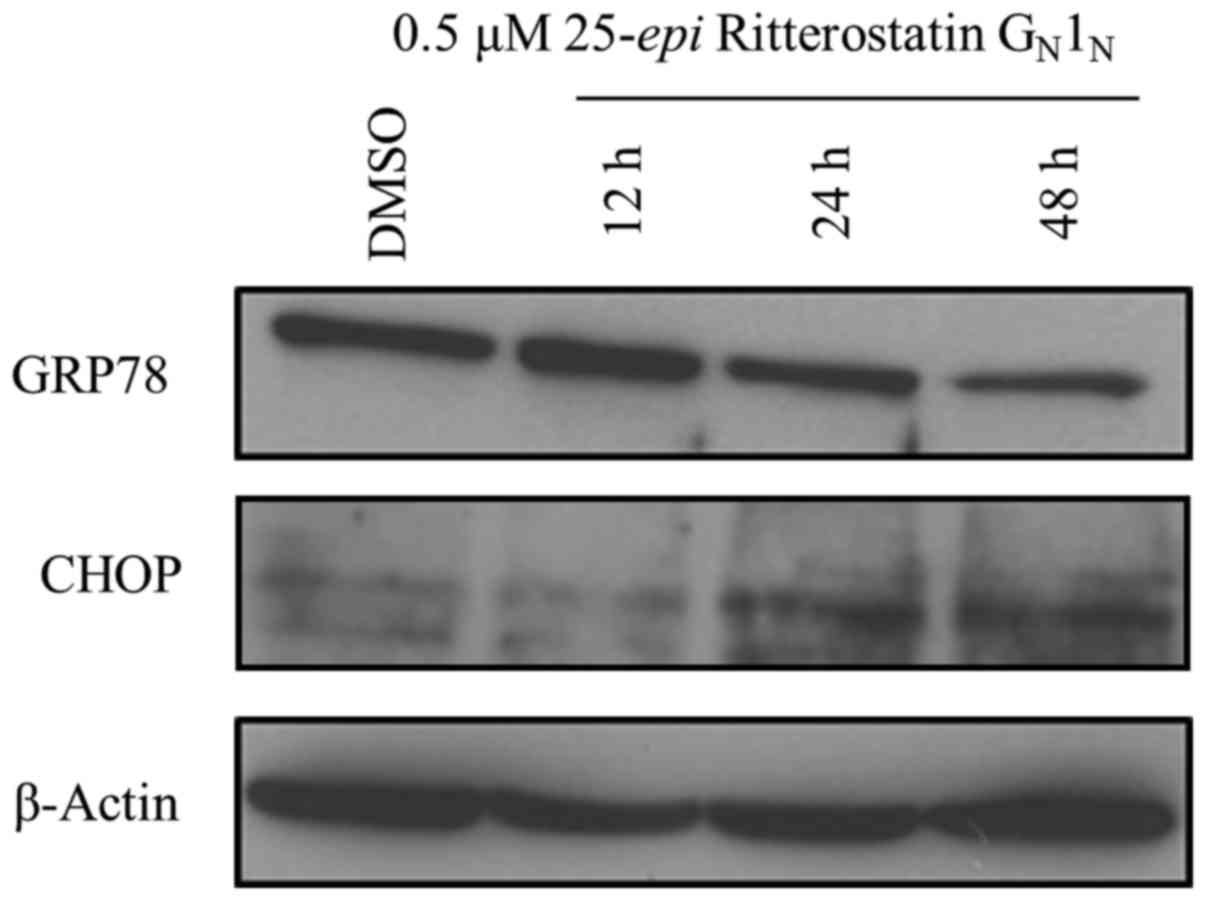

25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N induces endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

stress in melanoma cells

Several studies have indicated that ER stress can

lead to activation of autophagy in cells (41,42).

Glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) is thought to be a major

sensor of ER stress and is associated with melanoma progression and

increased drug resistance in melanoma and other cancers (18,52–54).

Since our findings indicated that autophagy was activated by

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N in melanoma

cells, we investigated the effect of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N on GRP78 expression. 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N triggered a time-dependent

decrease in GRP78 expression in A375 cells. (Fig. 4). Noteworthy, an initial activation

of GRP78 expression was observed at 12 h after treatment with

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N, before

decreasing at later time points. This early GRP78 activation might

be a result of its initial efforts to contain and neutralize ER

stress.

Simultaneously, we observed time-dependent

upregulated expression of CHOP, the ER stress marker protein known

to mediate cytotoxicity, in cells treated with 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N. Taken together, these

findings suggest that treatment with 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N triggered ER stress, leading to

autophagy and cell death.

25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N exhibits minimal toxicity in normal

melanocytes

To determine whether the effects of 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N were specific to melanoma

cells, we also treated normal melanocytes with 0.5 and 1 µM

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N and

performed Annexin V/propidium iodide staining to analyze cell

viability (Fig. 5A). We found that

96.6% of normal melanocytes (normalized to control) were viable

after treatment with 1µM 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N, compared with 36% of A375 cells treated

with 0.5µM 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N. Additionally, biochemical analysis for

changes in mitochondrial membrane potential indicated that the

normal melanocytes were resistant to the effect of 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N on mitochondrial membrane

integrity (Fig. 5B). Subsequent

immunoblotting analysis revealed no changes in the lipidation

expression profile of the autophagy marker protein LC3B (data not

shown). These findings indicate that the antitumor activity of

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N is specific

to melanoma cells, with limited toxicity in normal melanocytes.

25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N triggers inhibition of tumor growth in

vivo

Akt overexpression has been found to lead to rapid

tumor growth, increased angiogenesis, and a more pronounced

glycolytic mechanism in parental WM35 cells (55). Therefore, we used WM35 cells with

activated Akt expression (WM35 PKB cells) as a study model to

assess the antitumor activity of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N. WM35 PKB cells (2×106) were

injected subcutaneously into female athymic nude mice, followed by

randomizing the mice into two groups of five each. The treatment

group received 2 mg/kg 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N 3 times per week via intraperitoneal

injection, and the control group received PBS. Tumor volume and

mouse body weight were recorded. Our results showed that

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N

substantially suppressed melanoma tumor growth in the mouse

xenografts (Fig. 6A–C). In

addition, we found that body weight did not differ substantially

between the control (Fig. 6D) and

the treatment groups, suggesting that 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N does not cause any toxic effects in

mice.

Discussion

Malignant melanoma is one of the most aggressive

forms of cancer, with increasing incidence rates. Although multiple

clinical trials have been initiated with novel agents to treat

melanoma, very few have been successful, thus highlighting the need

to identify potential therapeutic agents through mechanistic

studies. Our results demonstrate that 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N exhibits antitumor activity in melanoma

cells by inducing autophagy and enhanced ER stress, with minimal

toxic effects in normal melanocytes, suggesting that further study

of 25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N as a

potential treatment for melanoma is necessary.

The chaperone protein GRP78 (also called BiP) acts

as the primary sensor of ER stress due to accumulation of unfolded

proteins in the ER lumen, which occurs as a result of oxidative

stress and cellular toxicity induced by calcium ionophores and

other agents (56). During ER

stress, GRP78 binds to these unfolded proteins, leading to the

release of resident ER transmembrane proteins such as PERK, ATF6,

and IRE1, which then activate downstream signaling cascades

promoting global repression of protein synthesis and subsequent

restoration of protein function (57–60).

GRP78 also supports cell survival by preventing caspase-7

activation and stabilization of mitochondrial function (61,62).

In melanoma, GRP78 has been linked to tumor progression and drug

resistance (18). Our results

showed that 25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N

inhibits GRP78 and activates CHOP expression in a time-dependent

fashion, leading to ER stress-mediated cell death.

Autophagy is a cellular self-digestive process that

facilitates degradation of long-lived proteins and damaged

organelles in cells to release energy and nutrients during stress

and starvation conditions. Numerous studies have indicated that

autophagy has a tumor-suppressive role in cancer (35). Work by Yue et al

demonstrated that activation of Beclin-1, the mammalian orthologue

for the yeast autophagy-related gene Atg6, inhibited in

vitro tumor cell proliferation and in vivo tumor growth

in mice (34), and also Sivridis

et al investigated the expression of two autophagy-related

proteins, Beclin-1 and LC3A, in 79 specimens of nodular cutaneous

melanoma (63). Their results

confirmed those from other researchers demonstrating that down

regulation of autophagic capacity is related to human

carcinogenesis (64,65). During autophagy, the light chain

protein LC3B is localized to autophagosomes and is therefore

considered a hallmark for autophagy. Our results demonstrate that

the cytotoxic effect of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N is mediated by autophagy. In addition to

increased lipidation of LC3B, we observed a collapse of the

mitochondrial membrane potential. Importantly, the combination of

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N with the

lysosomotrophic agent chloroquine resulted in rapid cell death.

Moreover, this induction of autophagy and loss of mitochondrial

membrane potential by 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N was not observed in normal melanocytes,

indicating that 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N has therapeutic selectivity to melanoma

cells.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study is

the first to characterize the in vitro and in vivo

antitumor effects of 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N in melanoma. We found that 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N inhibits melanoma cell

growth by activation of ER stress and autophagy. We also found that

intraperitoneal injection of 2 mg/kg 25-epi Ritterostatin

GN1N 3 times per week substantially reduced

the growth of melanoma in mice. Importantly, we observed no

significant change in body weight between mice treated with

25-epi Ritterostatin GN1N at this

dosage and control mice. These findings indicate that 25-epi

Ritterostatin GN1N could be a promising

treatment for melanoma. Nevertheless, additional in vivo and

clinical studies need to be conducted to ascertain the

effectiveness of this compound in inhibiting melanoma growth in

humans.

Abbreviations:

|

PI

|

propidium iodide

|

|

ER

|

endoplasmic reticulum

|

|

GRP78

|

glucose regulated protein 78

|

|

PBS

|

phosphate buffered saline

|

|

LC3

|

microtubule associated light chain

3

|

|

CHOP

|

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein

homologous protein

|

|

HSP70

|

heat shock protein 70

|

|

UPR

|

unfolded protein response

|

|

DAPK-1

|

death associated protein kinase

|

|

PERK

|

PKR-like EIF2α kinase

|

|

ATF-6

|

activation transcription factor-6

|

|

IRE-1

|

inositol requiring enzyme-1

|

|

BAX

|

Bcl-2 associated X

|

|

NHEM

|

normal human epidermal

melanocytes

|

|

DMSO

|

dimethyl sulfoxide

|

|

MTT

|

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetra-zolium bromide

|

|

FACS

|

fluorescence activated cell

sorting

|

|

Atg6

|

autophagy-related gene 6

|

References

|

1

|

Brown TJ and Nelson BR: Malignant

melanoma: A clinical review. Cutis. 63:275–278. 281–284.

1999.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Alberts B, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K and

Walter P: Molecular Biology of the Cell. 5th edition. Garland

Science; New York, NY: pp. 13922008

|

|

3

|

Braakman I and Bulleid NJ: Protein folding

and modification in the mammalian endoplasmic reticulum. Annu Rev

Biochem. 80:71–99. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Malhotra JD and Kaufman RJ: The

endoplasmic reticulum and the unfolded protein response. Semin Cell

Dev Biol. 18:716–731. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Jiang CC, Chen LH, Gillespie S, Kiejda KA,

Mhaidat N, Wang YF, Thorne R, Zhang XD and Hersey P: Tunicamycin

sensitizes human melanoma cells to tumor necrosis factor-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis by up-regulation of

TRAIL-R2 via the unfolded protein response. Cancer Res.

67:5880–5888. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Noda I, Fujieda S, Seki M, Tanaka N,

Sunaga H, Ohtsubo T, Tsuzuki H, Fan GK and Saito H: Inhibition of

N-linked glycosylation by tunicamycin enhances sensitivity to

cisplatin in human head-and-neck carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer.

80:279–284. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Denmeade SR, Jakobsen CM, Janssen S, Khan

SR, Garrett ES, Lilja H, Christensen SB and Isaacs JT:

Prostate-specific antigen-activated thapsigargin prodrug as

targeted therapy for prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst.

95:990–1000. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Treiman M, Caspersen C and Christensen SB:

A tool coming of age: Thapsigargin as an inhibitor of

sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPases. Trends Pharmacol Sci.

19:131–135. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Johnson AJ, Hsu AL, Lin HP, Song X and

Chen CS: The cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib perturbs

intracellular calcium by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum

Ca2+-ATPases: A plausible link with its anti-tumour

effect and cardiovascular risks. Biochem J. 366:831–837. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Oyadomari S and Mori M: Roles of

CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ.

11:381–389. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lee AS: The glucose-regulated proteins:

Stress induction and clinical applications. Trends Biochem Sci.

26:504–510. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Li J and Lee AS: Stress induction of

GRP78/BiP and its role in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 6:45–54. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Xing X, Lai M, Wang Y, Xu E and Huang Q:

Overexpression of glucose-regulated protein 78 in colon cancer.

Clin Chim Acta. 364:308–315. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Fernandez PM, Tabbara SO, Jacobs LK,

Manning FC, Tsangaris TN, Schwartz AM, Kennedy KA and Patierno SR:

Overexpression of the glucose-regulated stress gene GRP78 in

malignant but not benign human breast lesions. Breast Cancer Res

Treat. 59:15–26. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Shuda M, Kondoh N, Imazeki N, Tanaka K,

Okada T, Mori K, Hada A, Arai M, Wakatsuki T, Matsubara O, et al:

Activation of the ATF6, XBP1 and grp78 genes in human

hepatocellular carcinoma: A possible involvement of the ER stress

pathway in hepatocarcinogenesis. J Hepatol. 38:605–614. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Luk JM, Lam CT, Siu AF, Lam BY, Ng IO, Hu

MY, Che CM and Fan ST: Proteomic profiling of hepatocellular

carcinoma in Chinese cohort reveals heat-shock proteins (Hsp27,

Hsp70, GRP78) up-regulation and their associated prognostic values.

Proteomics. 6:1049–1057. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Arap MA, Lahdenranta J, Mintz PJ, Hajitou

A, Sarkis AS, Arap W and Pasqualini R: Cell surface expression of

the stress response chaperone GRP78 enables tumor targeting by

circulating ligands. Cancer Cell. 6:275–284. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhuang L, Scolyer RA, Lee CS, McCarthy SW,

Cooper WA, Zhang XD, Thompson JF and Hersey P: Expression of

glucose-regulated stress protein GRP78 is related to progression of

melanoma. Histopathology. 54:462–470. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

de Ridder GG, Ray R and Pizzo SV: A murine

monoclonal antibody directed against the carboxyl-terminal domain

of GRP78 suppresses melanoma growth in mice. Melanoma Res.

22:225–235. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Ranganathan AC, Zhang L, Adam AP and

Aguirre-Ghiso JA: Functional coupling of 38-induced up-regulation

of BiP and activation of RNA-dependent protein kinase-like

endoplasmic reticulum kinase to drug resistance of dormant

carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 66:1702–1711. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Rutkowski DT, Arnold SM, Miller CN, Wu J,

Li J, Gunnison KM, Mori K, Sadighi Akha AA, Raden D and Kaufman RJ:

Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of

pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol.

4:e3742006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang X, Batchvarova

N, Lightfoot RT, Remotti H, Stevens JL and Ron D: CHOP is

implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired

function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 12:982–995. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Matsumoto M, Minami M, Takeda K, Sakao Y

and Akira S: Ectopic expression of CHOP (GADD153) induces apoptosis

in M1 myeloblastic leukemia cells. FEBS Lett. 395:143–147. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Cho HY, Thomas S, Golden EB, Gaffney KJ,

Hofman FM, Chen TC, Louie SG, Petasis NA and Schönthal AH: Enhanced

killing of chemo-resistant breast cancer cells via controlled

aggravation of ER stress. Cancer Lett. 282:87–97. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Rabik CA, Fishel ML, Holleran JL, Kasza K,

Kelley MR, Egorin MJ and Dolan ME: Enhancement of cisplatin

[cisdiammine dichloroplatinum (II)] cytotoxicity by

O6-benzylguanine involves endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Pharmacol

Exp Ther. 327:442–452. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Sánchez AM, Martínez-Botas J,

Malagarie-Cazenave S, Olea N, Vara D, Lasunción MA and Díaz-Laviada

I: Induction of the endoplasmic reticulum stress protein

GADD153/CHOP by capsaicin in prostate PC-3 cells: A microarray

study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 372:785–791. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ravikumar B, Futter M, Jahreiss L,

Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, Massey DC, Menzies FM,

Narayanan U, Renna M, et al: Mammalian macroautophagy at a glance.

J Cell Sci. 122:1707–1711. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Klionsky DJ and Emr SD: Autophagy as a

regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science. 290:1717–1721.

2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A and

Kroemer G: Self-eating and self-killing: Crosstalk between

autophagy and apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 8:741–752. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM and

Klionsky DJ: Autophagy fights disease through cellular

self-digestion. Nature. 451:1069–1075. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Guo JY, Chen HY, Mathew R, Fan J,

Strohecker AM, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Kamphorst JJ, Chen G, Lemons JM,

Karantza V, et al: Activated Ras requires autophagy to maintain

oxidative metabolism and tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 25:460–470.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Maiuri MC, Malik SA, Morselli E, Kepp O,

Criollo A, Mouchel PL, Carnuccio R and Kroemer G: Stimulation of

autophagy by the p53 target gene Sestrin2. Cell Cycle. 8:1571–1576.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Tasdemir E, Maiuri MC, Galluzzi L, Vitale

I, Djavaheri-Mergny M, D'Amelio M, Criollo A, Morselli E, Zhu C,

Harper F, et al: Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nat

Cell Biol. 10:676–687. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yue Z, Jin S, Yang C, Levine AJ and Heintz

N: Beclin 1, an autophagy gene essential for early embryonic

development, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 100:15077–15082. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, Furuya N, Hibshoosh

H, Troxel A, Rosen J, Eskelinen EL, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, et al:

Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the beclin

1 autophagy gene. J Clin Invest. 112:1809–1820. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Gozuacik D, Bialik S, Raveh T, Mitou G,

Shohat G, Sabanay H, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T and Kimchi A:

DAP-kinase is a mediator of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced

caspase activation and autophagic cell death. Cell Death Differ.

15:1875–1886. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Zalckvar E, Berissi H, Mizrachy L,

Idelchuk Y, Koren I, Eisenstein M, Sabanay H, Pinkas-Kramarski R

and Kimchi A: DAP-kinase-mediated phosphorylation on the BH3 domain

of beclin 1 promotes dissociation of beclin 1 from Bcl-XL and

induction of autophagy. EMBO Rep. 10:285–292. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zalckvar E, Berissi H, Eisenstein M and

Kimchi A: Phosphorylation of Beclin 1 by DAP-kinase promotes

autophagy by weakening its interactions with Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL.

Autophagy. 5:720–722. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Shen J, Chen X, Hendershot L and Prywes R:

ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of

BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Dev

Cell. 3:99–111. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Okada T, Yoshida H, Akazawa R, Negishi M

and Mori K: Distinct roles of activating transcription factor 6

(ATF6) and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like

endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) in transcription during the

mammalian unfolded protein response. Biochem J. 366:585–594. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Ding WX, Ni HM, Gao W, Hou YF, Melan MA,

Chen X, Stolz DB, Shao ZM and Yin XM: Differential effects of

endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced autophagy on cell survival. J

Biol Chem. 282:4702–4710. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Yorimitsu T, Nair U, Yang Z and Klionsky

DJ: Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers autophagy. J Biol Chem.

281:30299–30304. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Bernales S, McDonald KL and Walter P:

Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during

the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 4:e4232006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, Morikawa K,

Kondo S, Kanemoto S, Murakami T, Taniguchi M, Tanii I, Yoshinaga K,

et al: Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic

reticulum stress. Mol Cell Biol. 26:9220–9231. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kanduluru AK, Banerjee P, Beutler JA and

Fuchs PL: A convergent total synthesis of the potent

cephalostatin/ritterazine hybrid -25-epi ritterostatin

GN1N. J Org Chem. 78:9085–9092. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Shoemaker RH: The NCI60 human tumour cell

line anticancer drug screen. Nat Rev Cancer. 6:813–823. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

von Schwarzenberg K and Vollmar AM:

Targeting apoptosis pathways by natural compounds in cancer: Marine

compounds as lead structures and chemical tools for cancer therapy.

Cancer Lett. 332:295–303. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Fan C, Wang W, Zhao B, Zhang S and Miao J:

Chloroquine inhibits cell growth and induces cell death in A549

lung cancer cells. Bioorg Med Chem. 14:3218–3222. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Yoon YH, Cho KS, Hwang JJ, Lee SJ, Choi JA

and Koh JY: Induction of lysosomal dilatation, arrested autophagy,

and cell death by chloroquine in cultured ARPE-19 cells. Invest

Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 51:6030–6037. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A,

Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y and Yoshimori T: LC3, a

mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome

membranes after processing. EMBO J. 19:5720–5728. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H,

Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M,

Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al: Guidelines for the use and

interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy.

8:445–544. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Papalas JA, Vollmer RT, Gonzalez-Gronow M,

Pizzo SV, Burchette J, Youens KE, Johnson KB and Selim MA: Patterns

of GRP78 and MTJ1 expression in primary cutaneous malignant

melanoma. Mod Pathol. 23:134–143. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zheng HC, Takahashi H, Li XH, Hara T,

Masuda S, Guan YF and Takano Y: Overexpression of GRP78 and GRP94

are markers for aggressive behavior and poor prognosis in gastric

carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 39:1042–1049. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Su R, Li Z, Li H, Song H, Bao C, Wei J and

Cheng L: Grp78 promotes the invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma.

BMC Cancer. 10:202010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Govindarajan B, Sligh JE, Vincent BJ, Li

M, Canter JA, Nickoloff BJ, Rodenburg RJ, Smeitink JA, Oberley L,

Zhang Y, et al: Overexpression of Akt converts radial growth

melanoma to vertical growth melanoma. J Clin Invest. 117:719–729.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Kaufman RJ: Stress signaling from the

lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: Coordination of gene

transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev.

13:1211–1233. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM,

Harding HP and Ron D: Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress

transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol.

2:326–332. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Schindler AJ and Schekman R: In vitro

reconstitution of ER-stress induced ATF6 transport in COPII

vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:17775–17780. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Shen J, Snapp EL, Lippincott-Schwartz J

and Prywes R: Stable binding of ATF6 to BiP in the endoplasmic

reticulum stress response. Mol Cell Biol. 25:921–932. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T and

Mori K: Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a

transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to

endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 10:3787–3799. 1999.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Reddy RK, Mao C, Baumeister P, Austin RC,

Kaufman RJ and Lee AS: Endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein

GRP78 protects cells from apoptosis induced by topoisomerase

inhibitors: Role of ATP binding site in suppression of caspase-7

activation. J Biol Chem. 278:20915–20924. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Sun FC, Wei S, Li CW, Chang YS, Chao CC

and Lai YK: Localization of GRP78 to mitochondria under the

unfolded protein response. Biochem J. 396:31–39. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Sivridis E, Koukourakis MI, Mendrinos SE,

Karpouzis A, Fiska A, Kouskoukis C and Giatromanolaki A: Beclin-1

and LC3A expression in cutaneous malignant melanomas: A biphasic

survival pattern for beclin-1. Melanoma Res. 21:188–195. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Wang J, Pan XL, Ding LJ, Liu DY, Da-Peng

Lei and Jin T: Aberrant expression of Beclin-1 and LC3 correlates

with poor prognosis of human hypopharyngeal squamous cell

carcinoma. PLoS One. 8:e690382013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Huang X, Bai HM, Chen L, Li B and Lu YC:

Reduced expression of LC3B-II and Beclin 1 in glioblastoma

multiforme indicates a downregulated autophagic capacity that

relates to the progression of astrocytic tumors. J Clin Neurosci.

17:1515–1519. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|