Introduction

Colorectal carcinoma (CRC) remains one of the most

common malignancies worldwide and represents a global health

problem (1). An increasing number

of Asian countries, including China, Japan, South Korea and

Singapore, have experienced a 2- to 4-fold increase in the

incidence of CRC over the last few decades (2). The pathogenesis of CRC ordinarily

occurs in a staged progression from normal colonic mucosa to

adenoma and finally to carcinoma over a period of ~7–10 years

(3–5). This sequenced progression over time

provides an opportunity for early diagnosis and treatment.

It has previously been indicated that delayed

diagnosis is the main reason for a poor prognosis (6). The traditional non-invasive and

invasive methods of screening modalities include fecal occult blood

testing, fecal immunochemical test, double-contrast barium enema,

flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy (7–9).

Although some of these screening modalities have been demonstrated

to reduce the rates of malignancy or mortality, there remains the

issue of reducing cancer-related mortality by removing premalignant

adenomas and early localized cancer prior to the onset of more

advanced stages. Therefore, an effective approach to early

screening, diagnosis and follow-up monitoring of CRC is

required.

Over the last few years, extensive investigations

have focused on serum tumor markers (STMs). In patients with CRC,

single STMs exhibit low sensitivity and specificity, whereas the

simultaneous measurement of several STMs may increase their

diagnostic accuracy (10). It was

demonstrated that the combined use of carcionembryonic antigen

(CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 was effective in the

screening and diagnosis of CRC (11). CA724 was previously identified as a

type of STM specific for gastric cancer (12) and the correlation between CA724 and

CRC has been attracting increasing attention (13).

Furthermore, due to the numerous characteristics

shared by colon carcinoma (CC) and rectal carcinoma (RC), the two

are discussed as a single entity. Whether CC and RC should be

considered as a single or two distinct entities remains

controversial (14). The aim of

the present study was to investigate serum CA724 levels in patients

with different clinical stages of CC and RC and analyze the

correlation between serum CA724 levels and the clinical stages of

CRC.

Patients and methods

Patients

In this study, a total of 100 patients (63 male and

37 female) with histologically confirmed CRC were investigated. The

patient sample was comprised of 51 patients with CC (32 male and 19

female) and 49 patients with RC (31 male and 18 female). The CC and

RC patients were classified into four stages according to the 2003

TNM classification. Stages I and II were considered as early-stage,

whereas stages III and IV were considered as advanced-stage

disease. The patients in the advanced-stage group had either lymph

node (stage III) or distant metastases (stage IV). Patient

information, such as gender, age and pathological TNM staging, is

summarized in Table I. The ethics

committee for the Second Affiliated Hospital of Dalian Medical

University provided approval for this study (Dalian, China)

| Table I.Clinicopathological characteristics of

100 CRC patients. |

Table I.

Clinicopathological characteristics of

100 CRC patients.

| Variables | No. of CC | No. of RC |

|---|

| Gender | | |

| Male | 32 | 31 |

| Female | 19 | 18 |

| Age (years) | | |

| ≤50 | 9 | 11 |

| >50 | 42 | 38 |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | |

| No | 18 | 22 |

| Yes | 33 | 27 |

| Distant

metastasis | | |

| No | 35 | 39 |

| Yes | 16 | 10 |

| Stage | | |

| I | 6 | 14 |

| II | 12 | 8 |

| III | 17 | 17 |

| IV | 16 | 10 |

Serum collection and CA724 assay

The values of CA724 were measured prior to the

patients receiving radiation treatment or chemotherapy. Blood

samples were collected, separated by centrifugation and the serum

samples were stored at −20°C until assays were performed. The CA724

kit was provided by Diagnostic Products Corporation (DPC, Tianjin,

China). The serum CA724 levels were determined with an

immunoradiometric gamma counter (DPC-GAMMA-C12; DPC). The patient

details were furnished by the First and Second Hospitals affiliated

to Dalian Medical University, between 2010 and 2012.

Statistical analysis

The CA724 levels were assessed in different groups

according to different site, TNM classification, gender, age and

metastatic status of the patients. Since the serum CA724 levels in

each group did not follow a normal distribution, the statistical

significance of the differences between the groups was calculated

by non-parametric statistics (Mann-Whitney and Kruskall-Wallis

tests). The centralized tendency of each group was described as

means plus standard error of the mean (SEM). All statistical tests

were performed using SPSS software, version 11.5 (SPSS Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Differences among CRC patients in

different groups

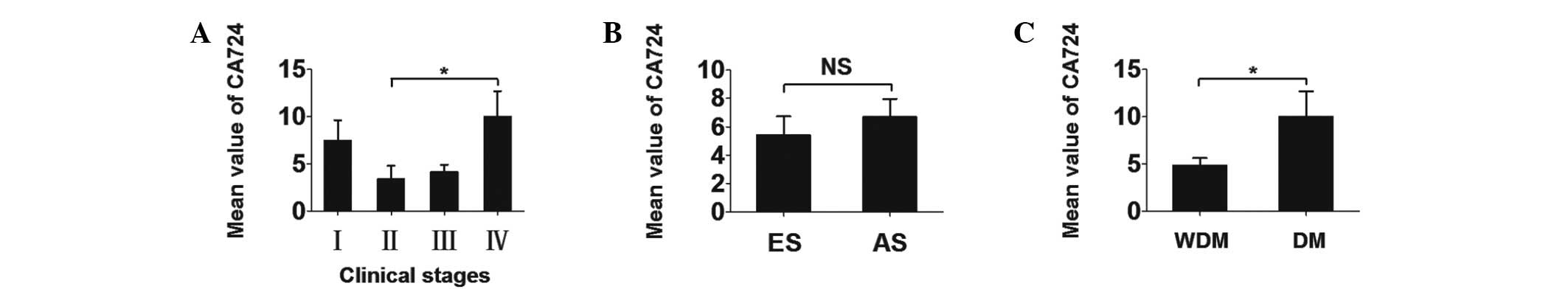

The mean serum CA724 values ± SEM were 6.808±1.462

U/ml in CC patients and 5.524±1.151 U/ml in RC patients, with no

statistically significant difference. Therefore, we first analyzed

the two types of cancer as a single entity. The different CA724

levels among CRC patients in different groups are presented in

Table II. The differences in the

CA724 values between CRC clinical stages were compared (Fig. 1). Further investigations indicated

that the mean serum CA724 concentrations ± SEM in patients with

early- and advanced-stage disease were 5.414±1.317 and 6.689±1.281

U/ml, respectively. The differences between the two groups were not

statistically significant. However, the differences between the CRC

patient group with and that without distant metastasis was

statistically significant (P=0.043).

| Table II.Differences in CA724 levels among

patients with colorectal carcinoma in different groups. |

Table II.

Differences in CA724 levels among

patients with colorectal carcinoma in different groups.

| Variables | Pt no. (CA724

levelsa) | P-value |

|---|

| Site | | NS |

| Colon | 51 (6.808±1.462) | |

| Rectum | 49 (5.524±1.151) | |

| Lymph node

metastasis | | NS |

| No | 40 (5.414±1.317) | |

| Yes | 60 (6.689±1.281) | |

| Distant

metastasis | | 0.043 |

| No | 74 (4.835±0.791) | |

| Yes | 26

(10.005±2.677) | |

| Stage | | NS |

| I | 20 (7.464±2.156) | |

| II | 20 (3.364±1.426) | |

| III | 34 (4.153±0.760) | |

| IV | 26

(10.005±2.677) | |

| Gender | | NS |

| Male | 63 (5.771±1.039) | |

| Female | 37 (7.148±1.798) | |

| Age | | NS |

| 30–50 | 20 (5.026±1.560) | |

| >50 | 80 (6.467±1.096) | |

To determine whether gender and age affected the

results in CRC patients mentioned above, the differences in the

serum CA724 values between genders was also assessed. Table III shows that there were no

significant differences between male and female CRC patients.

Furthermore, there were no significant differences between CRC

patients aged 30–50 years and those aged >50 years. Therefore,

the variables of gender and age were eliminated (Table II). Since there were distinct

differences among CRC patients, in order to interpret the

differences described above when assessing the two groups as a

single entity, we proceeded to analyze CC and RC separately.

| Table III.Differences in CA724 levels among CC

patients. |

Table III.

Differences in CA724 levels among CC

patients.

| Variables | Pt no. (CA724

levelsa) | P-value |

|---|

| Lymph node

metastasis | | <0.001 |

| No | 18 (1.663±0.237) | |

| Yes | 33 (9.614±2.109) | |

| Distant

metastasis | | <0.001 |

| No | 35

(3.143±0.493) | |

| Yes | 16

(14.985±3.875) | |

| Stage | | <0.001 |

| I | 6

(1.437±0.535) | |

| II | 12

(1.777±0.249) | |

| III | 17

(4.559±0.855) | |

| IV | 16

(14.985±3.875) | |

| Gender | | NS |

| Male | 32

(6.451±1.508) | |

| Female | 19

(7.409±3.051) | |

| Age (years) | | NS |

| 30–50 | 9

(4.664±1.160) | |

| >50 | 42

(7.267±1.755) | |

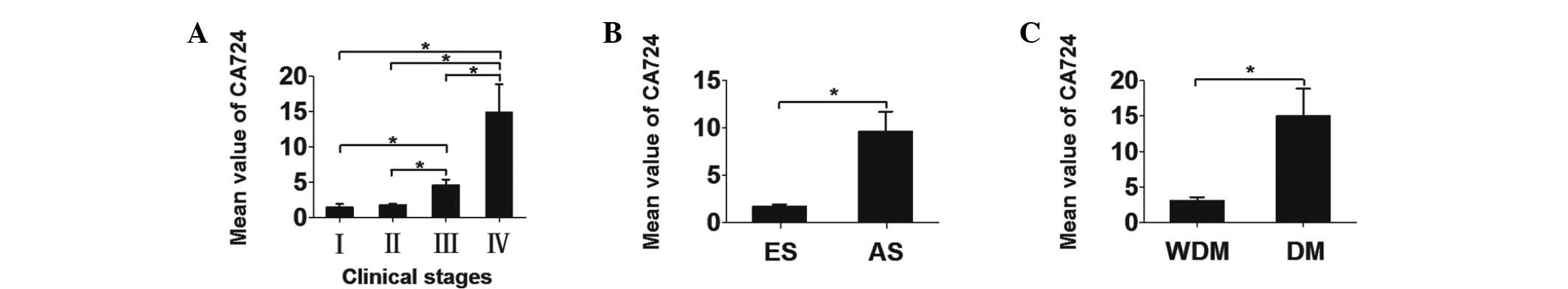

Ascending gradient among CC patients

The different CA724 levels among CC patients in

different groups are presented in Table III. There was an ascending gradient

of serum CA724 values with increasing clinical stage, except for

the difference between stages I and II (Fig. 2). The mean CA724 values ± SEM for

each stage were as follows: stage I, 1.437±0.535 U/ml; stage II,

1.777±0.249 U/ml; stage III, 4.559±0.855 U/ml; and stage IV,

14.985±3.875 U/ml. The differences in the CA724 values between

early- and advanced-stage disease were statistically significant

(P<0.001), as were those between patients with and those without

distant metastasis (P<0.001) (Fig.

2).

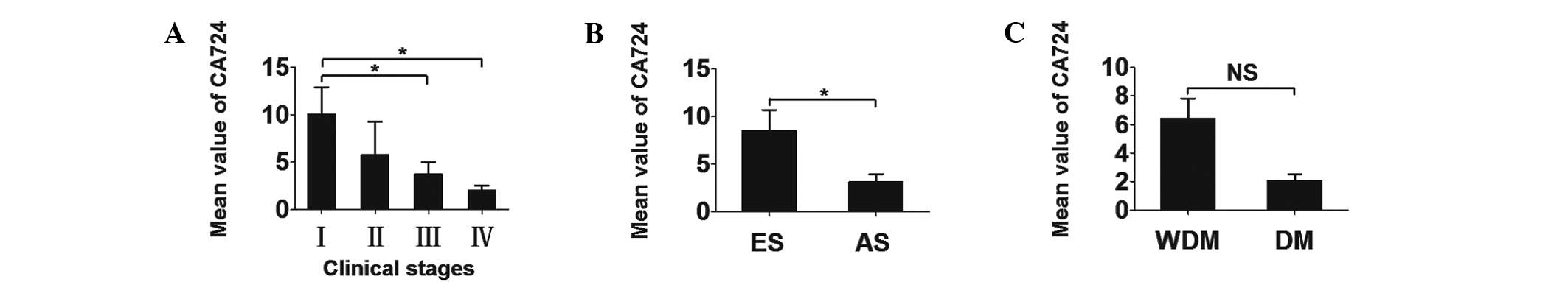

Descending gradient among RC

patients

The different CA724 levels among CC patients in

different groups are presented in Table IV. The mean serum CA724 values ±

SEM for each stage were as follows: stage I, 10.046±2.819 U/ml;

stage II, 5.745±3.506 U/ml; stage III, 3.748±1.277 U/ml; and stage

IV, 2.036±0.491 U/ml, these results are based on the data provided

in Table V. Therefore, a

descending gradient was identified among RC patients when each

clinical stage was separately analyzed (Fig. 3). Similarly, analysis with SPSS

software, version 11.5, revealed a significant correlation between

early- and advanced-stage disease (P=0.010). However, the

differences in the CA724 values between patients with and those

without distant metastasis did not reach a statistical significance

(Fig. 3).

| Table IV.Differences in CA724 levels among RC

patients. |

Table IV.

Differences in CA724 levels among RC

patients.

| Variables | Pt no. (CA724

levelsa) | P-value |

|---|

| Lymph node

metastasis | | 0.011 |

| No | 22

(8.482±2.196) | |

| Yes | 27

(3.114±0.830) | |

| Distant

metastasis | | NS |

| No | 39

(6.419±1.396) | |

| Yes | 10 (

2.036±0.491) | |

| Stage | | 0.022 |

| I | 14

(10.046±2.819) | |

| II | 8

(5.745±3.506) | |

| III | 17

(3.748±1.277) | |

| IV | 10

(2.036±0.491) | |

| Gender | | NS |

| Male | 31

(5.069±1.442) | |

| Female | 18

(6.308±1.905) | |

| Age (years) | | NS |

| 30–50 | 11

(5.322±2.739) | |

| >50 | 38

(5.583±1.261) | |

| Table V.Clinicopathological characteristics

of 100 patients with colorectal carcinoma. |

Table V.

Clinicopathological characteristics

of 100 patients with colorectal carcinoma.

| No. | Pathological

diagnosis | Site | Pathological TNM

staging | Lesion | Age/gender | CA724 |

|---|

| 1 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 61/M | 4.05 |

| 2 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 77/M | 1.19 |

| 3 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 61/M | 1.13 |

| 4 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T1N0M0 | Primary tumor | 63/F | 1.09 |

| 5 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 69/M | 0.59 |

| 6 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 58/F | 0.57 |

| 7 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 65/F | 3.44 |

| 8 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 61/F | 3.04 |

| 9 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 56/F | 2.78 |

| 10 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 75/F | 1.81 |

| 11 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 64/M | 1.71 |

| 12 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 48/M | 1.67 |

| 13 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 33/M | 1.49 |

| 14 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 51/F | 1.38 |

| 15 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 55/M | 1.24 |

| 16 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 67/M | 1.10 |

| 17 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 69/M | 0.85 |

| 18 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 48/F | 0.81 |

| 19 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N1M0 | Primary tumor | 65/M | 11.90 |

| 20 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 64/M | 10.22 |

| 21 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 45/M | 8.92 |

| 22 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N1M0 | Primary tumor | 52/F | 8.44 |

| 23 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 60/F | 6.44 |

| 24 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N1M0 | Primary tumor | 45/F | 6.31 |

| 25 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 51/M | 4.78 |

| 26 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N2M0 | Primary tumor | 61/M | 3.86 |

| 27 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N2M0 | Primary tumor | 62/F | 3.38 |

| 28 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 35/M | 2.90 |

| 29 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N2M0 | Primary tumor | 55/M | 2.05 |

| 30 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N2M0 | Primary tumor | 54/F | 1.82 |

| 31 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 70/F | 1.74 |

| 32 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 68/M | 1.67 |

| 33 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 67/M | 1.09 |

| 34 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 66/M | 1.03 |

| 35 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N1M0 | Primary tumor | 67/F | 0.95 |

| 36 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T2N0M1 | Primary tumor | 66/F | 57.79 |

| 37 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N0M1 | Primary tumor | 81/M | 43.30 |

| 38 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T2N0M1 | Primary tumor | 70/F | 19.99 |

| 39 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N2M1 | Primary tumor | 61/M | 19.90 |

| 40 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | TxNxM1 | Primary tumor | 64/F | 16.56 |

| 41 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N2M1 | Primary tumor | 56/M | 16.17 |

| 42 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | TxNxM1 | Primary tumor | 59/M | 15.15 |

| 43 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N1M1 | Primary tumor | 80/M | 12.23 |

| 44 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N2M1 | Primary tumor | 37/M | 10.76 |

| 45 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N2M1 | Primary tumor | 75/M | 7.37 |

| 46 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | TxNxM1 | Primary tumor | 74/M | 7.03 |

| 47 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N1M1 | Primary tumor | 42/M | 5.54 |

| 48 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M1 | Primary tumor | 42/M | 3.58 |

| 49 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T4N0M1 | Primary tumor | 74/F | 2.43 |

| 50 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | TxNxM1 | Primary tumor | 36/M | 1.32 |

| 51 | Adenocarcinoma | Colon | T3N0M1 | Primary tumor | 61/M | 0.64 |

| 52 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 66/M | 29.60 |

| 53 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 72/M | 26.03 |

| 54 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 79/M | 24.86 |

| 55 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 56/F | 18.30 |

| 56 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 55/M | 16.02 |

| 57 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 67/F | 6.48 |

| 58 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 73/F | 3.93 |

| 59 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 65/M | 3.91 |

| 60 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 57/M | 2.35 |

| 61 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 78/M | 2.14 |

| 62 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 62/F | 2.07 |

| 63 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 59/M | 1.95 |

| 64 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 79/F | 1.88 |

| 65 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N0M0 | Primary tumor | 72/F | 1.13 |

| 66 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 55/F | 29.85 |

| 67 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 67/F | 5.92 |

| 68 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 54/M | 4.27 |

| 69 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 55/F | 2.06 |

| 70 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 67/M | 1.40 |

| 71 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 66/F | 0.95 |

| 72 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N0M0 | Primary tumor | 67/F | 0.83 |

| 73 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N0M0 | Primary tumor | 73/M | 0.68 |

| 74 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N2M0 | Primary tumor | 38/F | 15.27 |

| 75 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 79/F | 14.91 |

| 76 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 68/M | 13.70 |

| 77 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N2M0 | Primary tumor | 48/M | 3.14 |

| 78 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 72/M | 3.13 |

| 79 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N2M0 | Primary tumor | 73/M | 2.93 |

| 80 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N1M0 | Primary tumor | 57/M | 1.48 |

| 81 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 55/M | 1.14 |

| 82 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T2N1M0 | Primary tumor | 71/M | 1.13 |

| 83 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 54/M | 1.05 |

| 84 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 47/F | 1.00 |

| 85 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N1M0 | Primary tumor | 48/M | 0.96 |

| 86 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N1M0 | Primary tumor | 69/M | 0.91 |

| 87 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4NxM0 | Primary tumor | 76/M | 0.86 |

| 88 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N1M0 | Primary tumor | 43/M | 0.80 |

| 89 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N2M0 | Primary tumor | 44/M | 0.67 |

| 90 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N2M0 | Primary tumor | 72/M | 0.63 |

| 91 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | TxNxM1 | Primary tumor | 74/F | 5.80 |

| 92 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | TxN1M1 | Primary tumor | 54/M | 2.34 |

| 93 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N1M1 | Primary tumor | 67/F | 0.95 |

| 94 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N1M1 | Primary tumor | 62/M | 3.33 |

| 95 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4NxM1 | Primary tumor | 43/F | 1.59 |

| 96 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4NxM1 | Primary tumor | 61/M | 2.26 |

| 97 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4N1M1 | Primary tumor | 67/M | 1.32 |

| 98 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | TxNxM1 | Primary tumor | 39/M | 1.10 |

| 99 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T4NxM1 | Primary tumor | 62/M | 1.04 |

| 100 | Adenocarcinoma | Rectum | T3N2M4 | Primary tumor | 53/F | 0.63 |

Discussion

This comprehensive integrative analysis of 100 CRC

patients indicated that serum CA724 levels may be of predictive

value in CRC, particularly in the analysis of clinical stage. As

regards CA724, recent studies have mainly focused on the

sensitivity and specificity of its diagnostic and early detection

value for recurrences. The combinations of CA724 with other STMs

were considered to be satisfactory (10,13,15–17).

In our study, we focused on the differences in the CA724 levels

among patients with different disease stages.

The differences in serum CA724 values between

patients with early- and advanced-stage disease suggest that CA724

may be associated with the metastasis of CC and RC. A similar

association was observed between CEA levels and CRC metastasis

(18,19). When comparing and analysing CC and

RC, we may surmise that the differences in the serum levels of

CA724 represent a sign of distant metastasis in CC. However, we did

not observe a statistically significant difference between RC

patients with and those without distant metastasis. We then

compared the clinical stages of CC and RC. Although we were unable

to verify a statistically significant difference for each stage

transition, there was a distinct variation tendency among the

stages. Therefore, we consider that monitoring serum CA724 levels

may be indicative of clinical stage, particularly in patients for

whom the determination of the pathological stage is difficult. The

CA724 value may reflect advanced stage, progression and metastasis

of CRC. Due to the widely variable prognosis of CRC, a previous

study attempted to identify a parameter useful in the selection of

patients who may be candidates for more tailored treatment

(20). Whether CA724 is such a

parameter requires further verification; however, our results

suggest that it has potential as a tumor marker. Considering the

association between CA724 and CRC, we may surmise the presence of

similar associations between other STMs and carcinomas.

Our study demonstrated the presence of two opposite

trends in the levels of CA724 according to the progression of the

clinical CRC stage. As was mentioned previously, there was an

ascending gradient among CC patients and a descending gradient

among RC patients. These two opposite trends possibly reflect

biological, advancing and metastatic differences between CC and RC.

Due to the similarities in morphology and configuration and the

fact that one is considered to be the continuation of the other, CC

and RC are often considered as a single disease entity. However, an

increasing number of studies refer to the differences between these

two types of cancer. Firstly, the colon embryologically originates

from the midgut and hindgut, whereas the rectum originates from the

cloaca. Furthermore, relevant studies have demonstrated that there

were differences regarding blood supply, biological function,

histochemical reactions and the level of mRNA expression (21–26).

Those studies indicated that the normal colon and rectum are

different. A previous study also reported that the prognosis of CC

is better compared to that of RC and that RC exhibits a higher

expression of CEA15. Additionally, a gene-level analysis

demonstrated that methylation and mutations were more common in the

right colon (27). All those

results suggested that there are biological differences between CC

and RC. The exact mechanism underlying the descending gradient in

the CA724 levels among RC patients has not been elucidated.

Although this study included a small number of

patients, the results regarding the association between CA724

levels and CRC patients were considered to be statistically

significant. Due to the small number of stage I CC patients (n=6),

further investigations are required to confirm these findings.

Furthermore, the exact nature of the association and the underlying

pathophysiological mechanisms of the opposite trends of serum CA724

in CC and RC require further investigation by future large

prospective studies.

In conclusion, we demonstrated a close correlation

between serum CA724 levels and tumor migration in CRC. The opposite

variation tendencies of CA724 levels in the different evolution

groups of CC and RC may reflect the differences between these two

types of cancer. The evaluation of serum CA724 levels, particularly

elevation in patients with CC, may be of monitoring and predictive

value and may also assist in the development of treatment

strategies for CRC patients.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants

from NSFC (31270867), the State Key Development Program of Basic

Research of China (2012CB822103) and the Department of Science and

Technology for Liaoning Province (2012225020).

References

|

1.

|

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al: Cancer

statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 59:225–249. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2.

|

Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, et al: Increasing

incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening.

Lancet Oncol. 6:871–876. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Hofstad B and Vatn M: Growth rate of colon

polyps and cancer. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 7:345–363.

1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, et al:

Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale.

Gastroenterology. 112:594–642. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Wong JJ, Hawkins NJ and Ward RL:

Colorectal cancer: a model for epigenetic tumorigenesis. Gut.

56:140–148. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Diallo Owono FK, Nguema Mve R, Ibaba J,

Mihindou C and Ondo N’dong F: Epidemiological and diagnostic

features of colorectal cancer in Libreville, Gabon. Med Trop

(Mars). 71:605–607. 2011.(In French).

|

|

7.

|

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force:

Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task

Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 149:627–637. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al

American Cancer Society Colorectal Cancer Advisory Group; US

Multi-Society Task Force; American College of Radiology Colon

Cancer Committee: Screening and surveillance for the early

detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a

joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US

Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American

College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 58:130–160. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9.

|

Dominic OG, McGarrity T, Dignan M and

Lengerich EJ: American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines for

Colorectal Cancer Screening 2008. Am J Gastroenterol.

104:2626–2627; author reply 2628–2629. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Lumachi F, Marino F, Orlando R, Chiara GB

and Basso SM: Simultaneous multianalyte immunoassay measurement of

five serum tumor markers in the detection of colorectal cancer.

Anticancer Res. 32:985–988. 2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Wang JY, Lu CY, Chu KS, et al: Prognostic

significance of pre- and postoperative serum carcinoembryonic

antigen levels in patients with colorectal cancer. Eur Surg Res.

39:245–250. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Chen XZ, Zhang WK, Yang K, et al:

Correlation between serum CA724 and gastric cancer: multiple

analyses based on Chinese population. Mol Biol Rep. 39:9031–9039.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Nicolini A, Ferrari P, Duffy MJ, et al:

Intensive risk-adjusted follow-up with the CEA, TPA, CA19.9, and

CA72.4 tumor marker panel and abdominal ultrasonography to diagnose

operable colorectal cancer recurrences: effect on survival. Arch

Surg. 145:1177–1183. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14.

|

Li M, Li JY, Zhao AL and Gu J: Colorectal

cancer or colon and rectal cancer? Clinicopathological comparison

between colonic and rectal carcinomas. Oncology. 73:52–57. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15.

|

Filella X, Molina R, Mengual PJ, et al:

Significance of CA72.4 in patients with colorectal cancer.

Comparison with CEA and CA19.9. J Nucl Biol Med. 35:158–161.

1991.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Yu JK, Yang MQ, Jiang TJ and Zheng S: The

optimal combination of serum tumor markers with bioinformatics in

diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma. J Zhejiang Univ. 33:407–410.

2004.(In Chinese).

|

|

17.

|

Newton KF, Newman W and Hill J: Review of

biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 14:3–17. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18.

|

Wiggers T, Arends JW, Verstijnen C, et al:

Prognostic significance of CEA immunoreactivity patterns in large

bowel carcinoma tissue. Br J Cancer. 54:409–414. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Kitadai Y, Radinsky R, Bucana CD, et al:

Regulation of carcinoembryonic antigen expression in human colon

carcinoma cells by the organ microenvironment. Am J Pathol.

149:1157–1166. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Seregni E, Ferrari L, Martinetti A and

Bombardieri E: Diagnostic and prognostic tumor markers in the

gastrointestinal tract. Semin Surg Oncol. 20:147–166. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21.

|

Araki K, Furuya Y, Kobayashi M, et al:

Comparison of mucosal microvasculature between the proximal and

distal human colon. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo). 45:202–206. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Skinner SA and O’Brien PE: The

microvascular structure of the normal colon in rats and humans. J

Surg Res. 61:482–490. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Devesa SS and Chow WH: Variation in

colorectal cancer incidence in the United States by subsite of

origin. Cancer. 71:3819–3826. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Shamsuddin AM, Phelps PC and Trump BF:

Human large intestinal epithelium: light microscopy,

histochemistry, and ultrastructure. Hum Pathol. 13:790–803. 1982.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Macfarlane GT, Gibson GR and Cummings JH:

Comparison of fermentation reactions in different regions of the

human colon. J Appl Bacteriol. 72:57–64. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26.

|

Mercurio MG, Shiff SJ, Galbraith RA and

Sassa S: Expression of cytochrome P450 mRNAs in the colon and the

rectum in normal human subjects. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

210:350–355. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27.

|

Cancer Genome Atlas Network: Comprehensive

molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer.

Nature. 487:330–337. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|