Introduction

Over the last few years, minimally invasive

laparoscopic surgery has become widespread. The indications for

such surgery have been extended to various conditions, including

additional bowel resection for stage I rectal cancer, radical

resection of stage II or III rectal cancer and palliative surgery

in patients with stage IV rectal cancer (1–6). With

conventional laparotomy (CL) for rectal cancer, it is difficult to

visualize areas such as the pelvic floor, the ventral part of the

bladder and the posterior to apical regions of the prostate and

almost blind manipulation is required. By contrast, endoscopic

magnification and viewing a monitor allows procedures to be

performed more safely, although the difficulty of rectal cancer

surgery increases with the depth of the lesion in the pelvis,

particularly lower rectal cancer located at the pelvic floor

(4). In Japan, pure

laparoscopy-assisted colorectal surgery (LACS) is frequently

performed using 5–6 ports, including a camera port and a small

incision of 35–45 mm for anastomosis. However, 4 forceps are

required for several procedures in pure LACS; therefore, at least 2

surgeons skilled in LACS must participate in the operation, while

the long operating time puts significant pressure on the

anesthesiologists and the availability of operating theaters. In

addition, LACS requires additional education and technical

guidance, as well as costly equipment and surgical materials; thus,

performing pure LACS at medium-sized hospitals with 400–500 beds is

associated with various problems (4–8). The

majority of the studies comparing pure LACS with CL demonstrated

that the former method is associated with a lower incidence of

wound infections and a shorter hospital stay, while achieving a

comparable or superior survival, with a more acceptable cosmetic

outcome (7–10). However, hand-assisted laparoscopic

surgery (HALS) and hybrid HALS (HH), which are based on

manipulation under direct vision, are more popular compared to pure

LACS in Europe and the United States. HH has the following

advantages: i) It allows safe palpation and grasping with the left

hand according to the techniques learned for laparotomy, which

allows smooth handling of large, heavy tumors and also allows the

surgeon to rapidly and easily pull the resected intestines away

from the pelvic floor under direct vision, as in laparotomy; ii)

Since HH is based on laparotomy, the operating time is relatively

short; and iii) it does not require a long time to learn the skills

necessary to perform HH (8,9,11–17). In Japan, CL accounts for ~50% of

rectal cancer surgery and pure LACS accounts for ~30–40%, with HALS

and small incision surgery constituting the remaining 10–20%

(18). The majority of the studies

comparing HALS and pure LACS have demonstrated that the operating

time is shorter with HALS and the rate of conversion to open

laparotomy is low; HALS may thus be considered as a surgical

technique between CL and pure LACS (8,9,19–23). In

Japan, HALS was widely used as an adjunctive method for a brief

period until pure LACS was introduced in 2000; however, the use of

HALS has noticeably decreased since the standardization of pure

LACS. Therefore, although certain single-center studies on HALS

have been performed overseas, no such report has been published in

Japan (9,24,25).

Accordingly, the objective of this study was to compare the

clinical outcome of HALS and CL in patients with rectal cancer

treated at a single center in Japan.

Patients and methods

Patients

A total of 850 patients underwent curative resection

of primary colorectal cancer at Tokai University Hachioji Hospital

(Tokyo, Japan) between April, 2002 and December, 2012. HALS was

employed to treat colorectal cancer from July, 2007 onwards and was

used in at least 350 patients. A total of 54 patients who underwent

conventional CL prior to the introduction of HALS were selected

from the 850 patients as stage-matched historical controls, whereas

the HALS group comprised 57 patients. The mean/median age was

65.4/65.0 years (range, 55–81 years) in the HALS group and

67.0/68.5 years (range, 35–92 years) in the CL group (P=0.095)

(Table IA). Of the 57 patients in the

hals group, 43 (75.4%) were male and 14 (24.6%) were female; of the

54 CL patients, 35 (64.8%) were male and 19 (35.2%) were female,

with no significant differences between the two groups (P=0.221)

(Table IB). As regards tumor

location, the tumor was located at the rectosigmoid region in 20

patients (35.1%) from the HALS group and 20 (37.0%) from the CL

group (P=0.831); in the upper rectum in 21 patients (36.8%) from

the HALS group and 14 (25.9%) from the CL group (P=0.216); and in

the lower rectum in 16 patients (28.1%) from the HALS group and 20

(37.0%) from the CL group (P=0.313). There were no significant

differences between the two groups (Table

IC). A total of 11 patients (19.3%) in the HALS group and 12

(22.2%) in the CL group underwent anterior resection (P=0.704); 39

patients (68.4%) in the HALS group and 33 (61.1%) in the CL group

underwent low anterior resection (P=0.420); and 7 patients (12.3%)

in the HALS group and 9 (16.7%) in the CL group underwent Miles'

operation (P=0.511). There were no significant differences between

the two groups (Table. IIA).

| Table I.Comparison of patient age, gender and

tumor location between the HALS (n=57) and CL (n=54) groups. |

Table I.

Comparison of patient age, gender and

tumor location between the HALS (n=57) and CL (n=54) groups.

| A, Comparison of

patient age |

|

|

|

|

| Age (years) | HALS | CL | P-valuea |

|

| Average | 65.4 | 67.0 | 0.095 |

| Median (range) | 65.0 (55–81) | 68.5 (35–92) |

|

|

| B, Comparison of

patient gender |

|

|

|

|

| Gender | HALS, no. (%) | CL, no. (%) | P-valueb |

|

| Male | 43 (75.4) | 35 (64.8) | 0.221 |

| Female | 14 (24.6) | 19 (35.2) |

|

|

| C, Comparison of

tumor location |

|

|

|

|

| Location | HALS, no. (%) | CL, no. (%) |

P-valueb |

|

| RS | 20 (35.1) | 20 (37.0) | 0.831 |

| Ra | 21 (36.8) | 14 (25.9) | 0.216 |

| Rb | 16 (28.1) | 20 (37.0) | 0.313 |

| Table II.Comparison of operative method and

tumor stage between the HALS (n=57) and CL (n=54) groups. |

Table II.

Comparison of operative method and

tumor stage between the HALS (n=57) and CL (n=54) groups.

| A, Comparison of

operative method |

|

|

|

|

| Operative

method | HALS, no. (%) | CL, no. (%) |

P-valuea |

|

| Anterior

resection | 11 (19.3) | 12 (22.2) | 0.704 |

| Low anterior

resection | 39 (68.4) | 33 (61.1) | 0.420 |

| Miles'

operation | 7 (12.3) | 9 (16.7) | 0.511 |

|

| B, Comparison of

tumor stage |

|

|

|

|

| Tumor stage | HALS, no. (%) | CL, no. (%) |

P-valuea |

|

| I | 17 (29.8) | 10 (18.5) | 0.165 |

| II | 14 (24.6) | 20 (37.0) | 0.154 |

| III | 26 (45.6) | 24 (44.4) | 0.901 |

The CL group included 54 patients who underwent

radical resection (stage I, 10 patients; stage II, 20 patients; and

stage III, 24 patients) prior to August, 2007 and received the same

postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy and follow-up as the those in

the HALS group (Table IIB). These

historical controls were matched for stage with the 57 patients who

underwent HALS (stage I, 17 patients; stage II, 14 patients; and

stage III, 26 patients) from 2007 onwards. For all patients in both

groups, the operative indications were as follows: A performance

status of 0–2, no severe cardiopulmonary complications, no lateral

lymph node metastasis or invasion of multiple organs and tumor not

filling the pelvic cavity prior to surgery (4,26,27).

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of Tokai University Hachioji Hospital and all the

patients provided written informed consent.

Treatment

CL involved a midline laparotomy with an incision of

30 cm or longer, whereas HALS was performed with 3 ports (rectum,

5/12/5 mm) and a vertical incision of ~45–55 mm in the umbilical

region (4,26,27). In

accordance with the Japanese General Rules for Classification of

Colorectal Carcinoma, a D2,3 resection was performed and at least

12 lymph nodes were harvested in all the patients from both groups

(28–30). No postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy

was administered to stage I patients; oral anticancer agents were

administered to stage II patients (400 mg/m2

tegafur/uracil and 3 g of polysaccharide K 5 days/week for at least

6 months); and modified 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (5-FU/LV) or

modified FOLFIRI (5-FU/LV + irinotecan: 85 mg/m2 of

irinotecan twice a month and 350 mg/m2 of 5-FU plus 150

mg/m2 LV on 5 consecutive days/month) was administered

to stage III patients for at least 6 months (31–36).

Survival

To identify metastasis/recurrence, we performed

ultrasound scan/computerized tomography (US/CT) and measured tumor

markers 3–4 times/year. If metastasis/recurrence was identified by

both US and CT, this was defined as metastasis/recurrence in the

present study (31–36). For patientsateach stage (I, II and

III) from the two groups, the 3-year relapse-free survival (3Y-RFS)

and 3-year overall survival (3Y-OS) were calculated. The mean and

median values of blood loss, operating time and postoperative

hospital stay, as well as the rate of conversion to open laparotomy

(only in the HALS group) were also calculated. Furthermore, we

compared postoperative complications, such as wound infection,

ileus, anastomotic leakage and re-operation, between the two

groups.

Statistical analysis

The Kaplan-Meier method was employed to estimate

3Y-RFS and 3Y-OS, while the log-rank test and hazard ratio (HR)

[(95% confidence interval (CI)] were used for comparisons between

the two groups. For other analyses, the χ2 test and

Mann-Whitney U test were used. P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference. Analyses were performed

with SPSS 21.0 statistical software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY,

USA).

Results

Comparison of survival between the two

groups

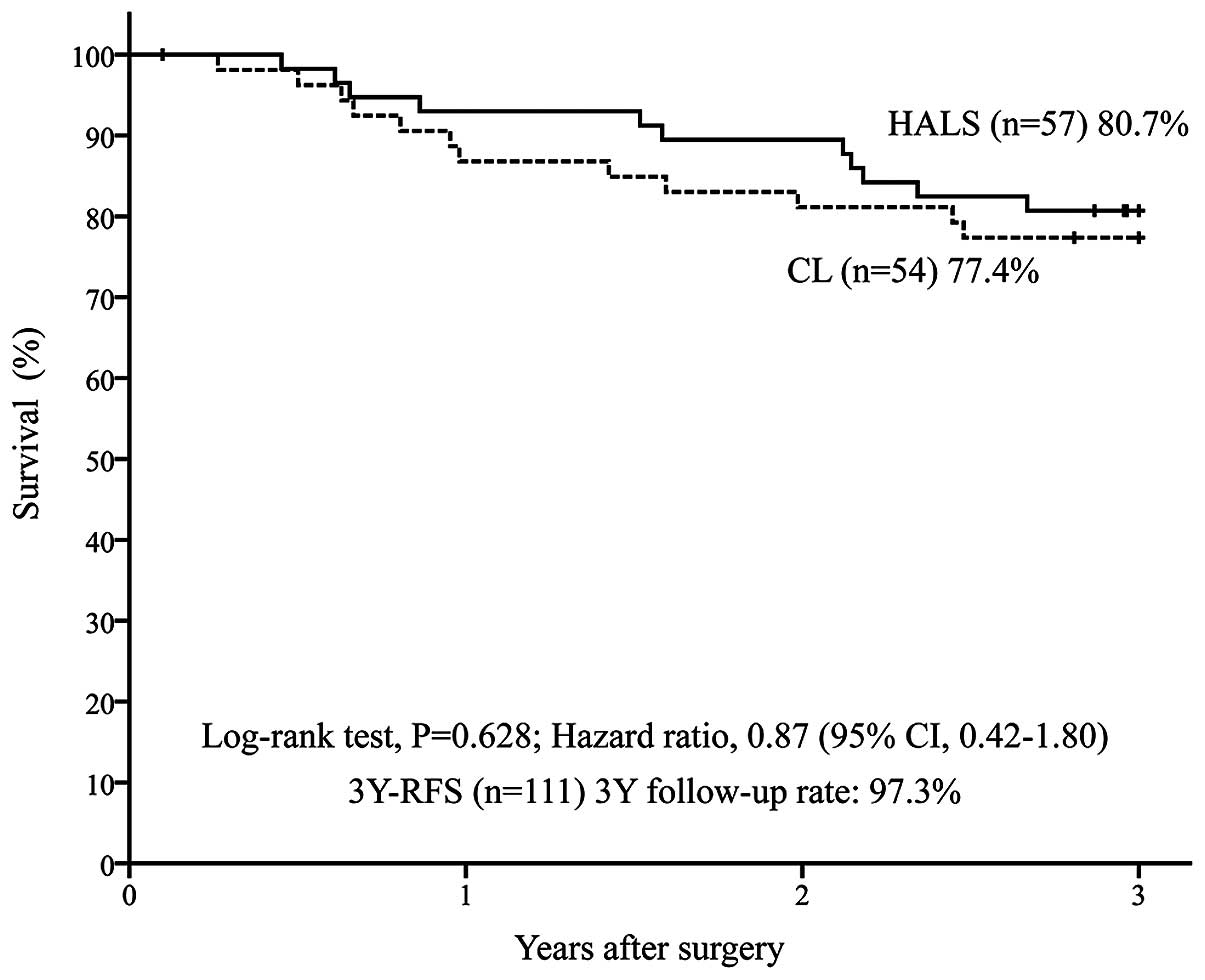

The 3Y-RFS of patients with stage I, II and III

disease (n=111) was 80.7% in the HALS group (n=57) and 77.4% in the

CL group (n=54) [P=0.628; HR=0.87 (95% CI: 0.42–1.80)] (Fig. 1). In addition, the 3Y-OS was 96.5% in

the HALS group (n=57) vs. 86.8% in the CL group (n=54) [P=0.064;

HR=0.27 (95% CI: 0.06–1.25)] (Fig.

2). The 3-year follow-up rate was 98.3% in the HALS group and

96.3% in the CL group (mean, 97.3%).

Intraoperative factors and hospital

stay

The mean/median intraoperative blood loss was

344.0/247.0 (range, 15–1969) ML in the HALS group (n=57) and

807.5/555.5 (121–4293) ML in the CL group (n=54) (P<0.001)

(Table III). The mean/median

operating time was 3 h 51 min/3 h 34 min (1 h 57 min-7 h 49 min) in

the HALS group (n=57) and 3 h 52 min/3 h 38 min (2 h 06 min-7 h 12

min) in the CL group (n=54) (P=0.454) (Table III). The mean/median postoperative

hospital stay was 19.8/17.0 (8–55) days in the HALS group (n=57)

and 25.5/18.5 (12–97) days in the CL group (n=54) (P=0.039)

(Table III).

| Table III.Intraoperative factors and hospital

stay in the HALS and CL groups. |

Table III.

Intraoperative factors and hospital

stay in the HALS and CL groups.

| Variables | HALS (n=57) | CL (n=54) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Blood

lossb |

|

| <0.001 |

|

Mean | 344.0 ml | 807.5 ml |

|

| Median

(range) | 247.0 (15–1,969)

ml | 555.5 (121–4,293)

ml |

|

| Operating time |

|

|

|

|

Mean | 3 h 51 min | 3 h 52 min | 0.454 |

| Median

(range) | 3 h 34 min (1 h 57

min–7 h 49 min) | 3 h 38 min (2 h 06

min–7 h 12 min) |

|

| Postoperative

hospital stay |

|

|

|

|

Mean | 19.8 days | 25.5 days | 0.039 |

| Median

(range) | 17.0 (8–55)

days | 18.5 (12–97)

days |

|

Postoperative complications

In the HALS group (n=57), the postoperative

complications included wound infection in 4 patients (7.0%), ileus

in 4 patients (7.0%), anastomotic leakage in 3 patients (5.3%),

urinary tract injury in 1 patient (1.8%) and re-operation in 2

patients (3.5%). There were no cases of conversion to open

laparotomy (0.0%) (Table IV). In the

CL group (n=54), these complications occurred in 9 (16.7%), 2

(3.7%), 3 (5.6%), 4 (7.4%) and 3 patients (5.6%), respectively;

there were no significant differences in the incidence of

complications between the two groups (Table IV).

| Table IV.Postoperative complications in the

HALS and CL groups. |

Table IV.

Postoperative complications in the

HALS and CL groups.

| Complications | HALS, no (%)

(n=57) | CL, no (%)

(n=54) |

P-valuea |

|---|

| Wound

infection | 4 (7.0) | 9 (16.7) | 0.114 |

| Ileus | 4 (7.0) | 2 (3.7) | 0.440 |

| Anastomotic

leakage | 3 (5.3) | 3 (5.6) | 0.946 |

| Urinary tract

injury | 1 (1.8) | 4 (7.4) | 0.151 |

| Re-operation | 2 (3.5) | 3 (5.6) | 0.603 |

| Others | 3 (5.3) | 5 (9.3) | 0.416 |

| Conversion to

CL | 0 (0.0) |

|

|

Discussion

In Japan, ~30–40% of rectal cancer surgeries are

performed by pure LACS, CL accounts for ~50%, while HALS and small

incision surgery are used for the remaining 10–20% (18). Since pure LACS has rapidly been

adopted over the last few years, several studies comparing pure

LACS with CL or HALS have been reported (8,9,19–23).

However, there is a major problem with the majority of the studies.

Usually, single-center comparison of surgical procedures employs

the CL group as a control; however, it is difficult to avoid bias

of background factors in studies of pure LACS or HALS, as these

procedures tend to be used for low-risk patients with a relatively

good general condition, who are able to tolerate the oblique

position with the head down, or patients with early-stage disease.

In addition, it may be difficult to achieve unification of

second-line treatment, including postoperative chemotherapy and

radiotherapy, as well as treatment following recurrence (4–10).

Moreover, if national clinical databases or guidelines are used as

controls, the study becomes a stage-stratified comparison of

outcomes with the national standards, which is not appropriate for

comparing surgical procedures. In our study, the CL group was

selected from patients who underwent surgery prior to the

introduction of HALS and we ensured that they were matched for

stage and received the same postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy as

the HALS group. All operations in both groups were performed by

Mukai et al (4,27), so the management of stage I, II and

III rectal cancer was standardized and at least 6 months of

treatment was completed by >80% of the patients in the two

groups (data not shown). In addition, <20% of the patients were

censored from our database, including those with unknown

details/dropout, which conforms to the Japanese Society for Cancer

of the Colon and Rectum Guidelines 2010 for the Treatment of

Colorectal Cancer and the database used in this study had a total

censored rate of 11.9% for the HALS group vs. 1.8% for the CL group

(P=0.001, data not shown). Furthermore, all the patients were

followed up for ≥3 years, with a 3-year follow-up rate of 98.3% for

the HALS group and 96.3% for the CL group. We are planning to

perform a final analysis in the next 2 years.

Studies comparing pure LACS with CL have identified

problems with the former, including a longer operating time and

increased cost, although the hospital stay is shorter and analgesic

use is decreased (7–10). There are also other problems with

performing pure LACS at medium-sized hospitals with 400–500 beds,

including the need for skilled surgeons, the training requirements,

the pressure on the anesthesiologists due to longer operations,

longer occupation of operating theaters and greater consumption of

materials. The comparison of pure LACS with HALS has also

identified problems, such as the slower learning curve for pure

LACS, additional time required and differences in the conversion

rate to open surgery (8,9,19–23). It has been reported that HALS is

associated with a markedly lower conversion rate compared to pure

LACS, with the rate being 0.0% (0/57 patients) in our study. This

result indicates that preoperative diagnosis and our indications

for HALS were strict and appropriate (2,4,7). In addition, there was less blood loss

and a shorter hospital stay with HALS compared to CL, suggesting

that HALS may be performed safely based on strict indications by

employing the magnified view obtained with laparoscopy.

In conclusion, HALS is a safe and reliable procedure

that utilizes the same left-hand manipulation as CL and allows

palpation/touch as it is positioned between pure LACS and CL. Since

HALS may be performed relatively easily at a low cost, we consider

it to be an excellent therapeutic option that deserves

re-evaluation, particularly in Japan, due to the decreasing

availability of surgeons and anesthesiologists.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the

Hand-Assisted Laparoscopic Surgery Research Group (grant no.

2012-5007; Tokai University Hachioji Hospital, Hachioji, Tokyo,

Japan) and the Research and Study Program of Tokai University

Educational System General Research Organization (grant no.

2012-03; Tokai University Hospital, Isehara, Kanagawa, Japan).

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

HALS

|

hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery

|

|

CL

|

conventional laparotomy

|

|

LACS

|

laparoscopy-assisted colorectal

surgery

|

References

|

1

|

Franklin ME Jr, Rosenthal D, Abrego-Medina

D, Dorman JP, Glass JL, Norem R and Diaz A: Prospective comparison

of open vs. laparoscopic colon surgery for carcinoma. Five-year

results. Dis Colon Rectum. 39 (Suppl 10):S35–S46. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Yano H, Ohnishi T, Kanoh T and Monden T:

Hand-assisted laparoscopic low anterior resection for rectal

carcinoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 15:611–614. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Mukai M, Tanaka A, Tajima T, Fukasawa M,

Yamagiwa T, Okada K, Sato K, Tobita K, Oida Y and Makuuchi H:

Two-port hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery for the 2-stage

treatment of a complete bowel obstruction by left colon cancer: A

case report. Oncol Rep. 19:875–879. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mukai M, Kishima K, Tajima T, Hoshikawa T,

Yazawa N, Fukumitsu H, Okada K, Ogoshi K and Makuuchi H: Efficacy

of hybrid 2-port hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery (Mukai's

operation) for patients with primary colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep.

22:893–899. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Koh DC, Law CW, Kristian I, Cheong WK and

Tsang CB: Hand-assisted laparoscopic abdomino-perineal resection

utilizing the planned end colostomy site. Tech Coloproctol.

14:201–206. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Guerrieri M, Campagnacci R, De Sanctis A,

Lezoche G, Massucco P, Summa M, Gesuita R, Capussotti L, Spinoglio

G and Lezoche E: Laparoscopic versus open colectomy for TNM stage

III colon cancer: Results of a prospective multicenter study in

Italy. Surg Today. 42:1071–1077. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Chung CC, Ng DC, Tsang WW, Tang WL, Yau

KK, Cheung HY, Wong JC and Li MK: Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus

open right colectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg.

246:728–733. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Yin WY, Wei CK, Tseng KC, Lin SP, Lin CH,

Chang CM and Hsu TW: Open colectomy versus laparoscopic-assisted

colectomy supported by hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy for

resectable colorectal cancer: A comparative study with minimum

follow-up of three years. Hepatogastroenterology. 56:998–1006.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Pendlimari R, Holubar SD, Pattan-Arun J,

Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Pemberton JH and Cima RR: Hand-assisted

laparoscopic colon and rectal cancer surgery: Feasibility,

short-term, and oncological outcomes. Surgery. 148:378–385. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Aimaq R, Akopian G and Kaufman HS:

Surgical site infection rates in laparoscopic versus open

colorectal surgery. Am Surg. 77:1290–1294. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Nakajima K, Lee SW, Cocilovo C, Foglia C,

Sonoda T and Milsom JW: Laparoscopic total colectomy: Hand-assisted

vs. standard technique. Surg Endosc. 18:582–586. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Kang JC, Chung MH, Chao PC, Yeh CC, Hsiao

CW, Lee TY and Jao SW: Hand-assisted laparoscopic colectomy vs.

open colectomy: A prospective randomized study. Surg Endosc.

18:577–581. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ringley C, Lee YK, Iqbal A, Bocharev V,

Sasson A, McBride CL, Thompson JS, Vitamvas ML and Oleynikov D:

Comparison of conventional laparoscopic and hand-assisted oncologic

segmental colonic resection. Surg Endosc. 21:2137–2141. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Young-Fadok TM: Colon cancer: Trials,

results, techniques (LAP and HALS), future. J Surg Oncol.

96:651–659. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Tjandra JJ, Chan MK and Yeh CH:

Laparoscopic- vs. hand-assisted ultralow anterior resection: A

prospective study. Dis Colon Rectum. 51:26–31. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Pattana-arun J, Sahakitrungruang C,

Atithansakul P, Tantiphlachiva K, Khomvilai S and Rojanasakul A:

Multimedia article. Hand-assisted laparoscopic total mesorectal

excision: A stepwise approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 52:17872009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Oncel M, Akin T, Gezen FC, Alici A and

Okkabaz N: Left inferior quadrant oblique incision: A new access

for hand-assisted device during laparoscopic low anterior resection

of rectal cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 19:663–666. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kitano S, Yamashita N, Shiraishi N, et al:

11th Nationwide surgery of endoscopic surgery in Japan. J Jpn Soc

Endoscopic Surg. 17:595–611. 2012.(In Japanese).

|

|

19

|

CimA R and Pemberton JH: How a hand-

assist can help in lap colectomy. Contemp Surg. 63:19–23. 2007.

|

|

20

|

Cima RR, Pattana-arun J, Larson DW, Dozois

EJ, Wolff BG and Pemberton JH: Experience with 969 minimal access

colectomies: The role of hand-assisted laparoscopy in expanding

minimally invasive surgery for complex colectomies. J Am Coll Surg.

206:946–952. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Sheng QS, Lin JJ, Chen WB, Liu FL, Xu XM,

Lin CZ, Wang JH and Li YD: Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus open

right hemicolectomy: Short-term outcomes in a single institution

from China. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 22:267–271. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Ng LW, Tung LM, Cheung HY, Wong JC, Chung

CC and Li MK: Hand-assisted laparoscopic versus total laparoscopic

right colectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis.

14:e612–e617. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sim JH, Jung EJ, Ryu CG, Paik JH, Kim G,

Kim SR and Hwang DY: Short-term outcomes of hand-assisted

laparoscopic surgery vs. open surgery on right colon cancer: A

case-controlled study. Ann Coloproctol. 29:72–76. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Meshikhes AW, El Tair M and Al Ghazal T:

Hand-assisted laparoscopic colorectal surgery: Initial experience

of a single surgeon. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 17:16–19. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tajima T, Mukai M, Yamazaki M, Higami S,

Yamamoto S, Hasegawa S, Nomura E, Sadahiro S, Yasuda S and Makuuchi

H: Comparison of hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery and

conventional laparotomy for colorectal cancer: Interim results from

a single institution. Oncol Lett. 8:627–632. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mukai M, Fukasawa M, Kishima K, Iizuka S,

Fukumitsu H, Yazawa N, Tajima T, Nakamura M and Makuuchi H:

Trans-anal reinforcing sutures after double stapling for lower

rectal cancer: Report of two cases. Oncol Rep. 21:335–339.

2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mukai M, Sekido Y, Hoshikawa T, Yazawa N,

Fukumitsu H, Okada K, Tajima T, Nakamura M and Ogoshi K: Two-stage

treatment (Mukai's method) with hybrid 2-port HALS (Mukai's

operation) for complete bowel obstruction by left colon cancer or

rectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 24:25–30. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Mukai M, Ito I, Mukoyama S, Tajima T,

Saito Y, Nakasaki H, Sato S and Makuuchi H: Improvement of 10-year

survival by Japanese radical lymph node dissection in patients with

Dukes' B and C colorectal cancer: A 17-year retrospective study.

Oncol Rep. 10:927–934. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon

and Rectum (JSCCR), . General Rules for Clinical and Pathological

Studies on Cancer of the Colon, Rectum and Anus. 7th. revised

version. Kanehara Shuppan; Tokyo, Japan: 2009

|

|

30

|

Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon

and Rectum, . JSCCR Guidelines 2010 for the Treatment of Colorectal

Cancer. Kanehara & Co., Ltd; Tokyo, Japan: 2010

|

|

31

|

Mukai M, Tajima T, Nakasaki H, Sato S,

Ogoshi K and Makuuchi H: Efficacy of postoperative adjuvant oral

immunochemotherapy in patients with Dukes' B colorectal cancer. Ann

Cancer Res Therap. 11:201–214. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Mukai M, Tajima T, Nakasaki H, Sato S,

Ogoshi K and Makuuchi H: Efficacy of postoperative adjuvant oral

immunochemotherapy in patients with Dukes' C colorectal cancer. Ann

Cancer Res Therap. 11:215–229. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ito I, Mukai M, Ninomiya H, Kishima K,

Tsuchiya K, Tajima T, Oida Y, Nakamura M and Makuuchi H: Comparison

between intravenous and oral postoperative adjuvant

immunochemotherapy in patients with stage II colorectal cancer.

Oncol Rep. 20:1189–1194. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Ito I, Mukai M, Ninomiya H, Kishima K,

Tsuchiya K, Tajima T, Nakamura M and Makuuchi H: Comparison between

intravenous and oral postoperative adjuvant immunochemotherapy in

patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 20:1521–1526.

2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Mukai M, Okada K, Fukumitsu H, Yazawa N,

Hoshikawa T, Tajima T, Hirakawa H, Ogoshi K and Makuuchi H:

Efficacy of 5-FU/LV plus CPT-11 as first-line adjuvant chemotherapy

for stage IIIa colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep. 22:621–629. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Mukai M, Kishima K, Uchiumi F, Ishibashi

E, Fukasawa M, Tajima T, Nakamura M and Makuuchi H: Clinical

comparison of QOL and adverse events during postoperative adjuvant

chemotherapy in outpatients with node-positive colorectal cancer or

gastric cancer. Oncol Rep. 21:1061–1066. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|