Introduction

Pyomyoma (suppurative leiomyoma) is a rare, but

life-threatening, condition resulting from infarction and infection

of uterine leiomyoma (1,2). Incidence of pyomyoma has decreased due

to the development of antibiotics. Since 1945, only 50 pyomyoma

cases have been documented in the literature, with a mortality rate

of 6% (3/50) (3–5). The most likely cause of mortality was

delayed and difficult diagnosis. Although the triad of pyomyoma are

sepsis, leiomyoma, and no other source of infection (5), it may present with silent or

non-specific symptoms, which results in delayed diagnosis and

treatment. Visualization of intratumoral gas formation may be

suggestive of pyomyoma, but has not been consistently reported in

all cases. Furthermore, large abdominal complex masses are likely

to be first suspected as pelvic malignancies if found incidentally

in perimenopausal women.

The present study experienced a rare case of large

uterine pyomyoma in a perimenopausal woman who presented with

anemia gravis, severe inflammatory reaction and cachexia. A total

of 50 reported cases of pyomyoma in the literature since 1945 were

also studied.

Case report

A 53-year-old multigravida woman with 7 months of

amenorrhea was referred to the Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology (Wakayama Medical University, Wakayama, Japan) due to

gradual abdominal distension starting 2 years previously. The

patient exhibited muscle weakness and walking difficulty, but no

fever, abdominal pain or metrorrhagia. Her abdomen was swollen to

the size of a beach ball, with a 126 cm abdominal circumference and

body weight of 84.1 kg. An intrauterine device (IUD) had been

inserted following her third birth, and no history of any lower

abdominal or pelvic discomfort, leiomyoma, pelvic surgery, or other

predisposing factors were known. The present study was unable to

determine the uterine cervix with pelvic examination due to its

deviation, and was unable to acquire cytopathological findings of

the cervix and endometrium. Transvaginal and transabdominal

ultrasound examinations revealed a large abdominal mass with

heterogeneous echogenicity. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large unilocular mass with an

irregular surface and thickened wall, occupying the abdominal

cavity without gas formation (Fig.

1). Contrast CT revealed an expanded branch of the left

internal iliac artery, which was suspected to be the uterine

artery, surrounding the mass (Fig.

1B). Hemoglobin levels were 5.7 g/dl, white blood cell count

was 57,300/µl and C-reactive protein was elevated to 20.24 mg/dl.

Cancer antigen (CA)125 was also elevated to 200 U/ml. Blood and

vaginal cultures were negative. Possible diagnoses of the large

abdominal mass included gynecologic tumor types (benign or

malignant ovarian tumor, uterine sarcoma or pyometra) and

gastrointestinal stromal tumor or mucocele of the appendix.

Gastroscopy revealed no specific findings and colonoscopy revealed

difficulty of insertion above the sigmoid colon due to pressure

from the mass. Due to the finding of the uterine artery by contrast

CT, the origin of the mass was suspected to be the uterus.

Following antibiotic medication and blood transfusion, the patient

underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral

salpingo-oophorectomy. Ureteral stents were indwelled in each side

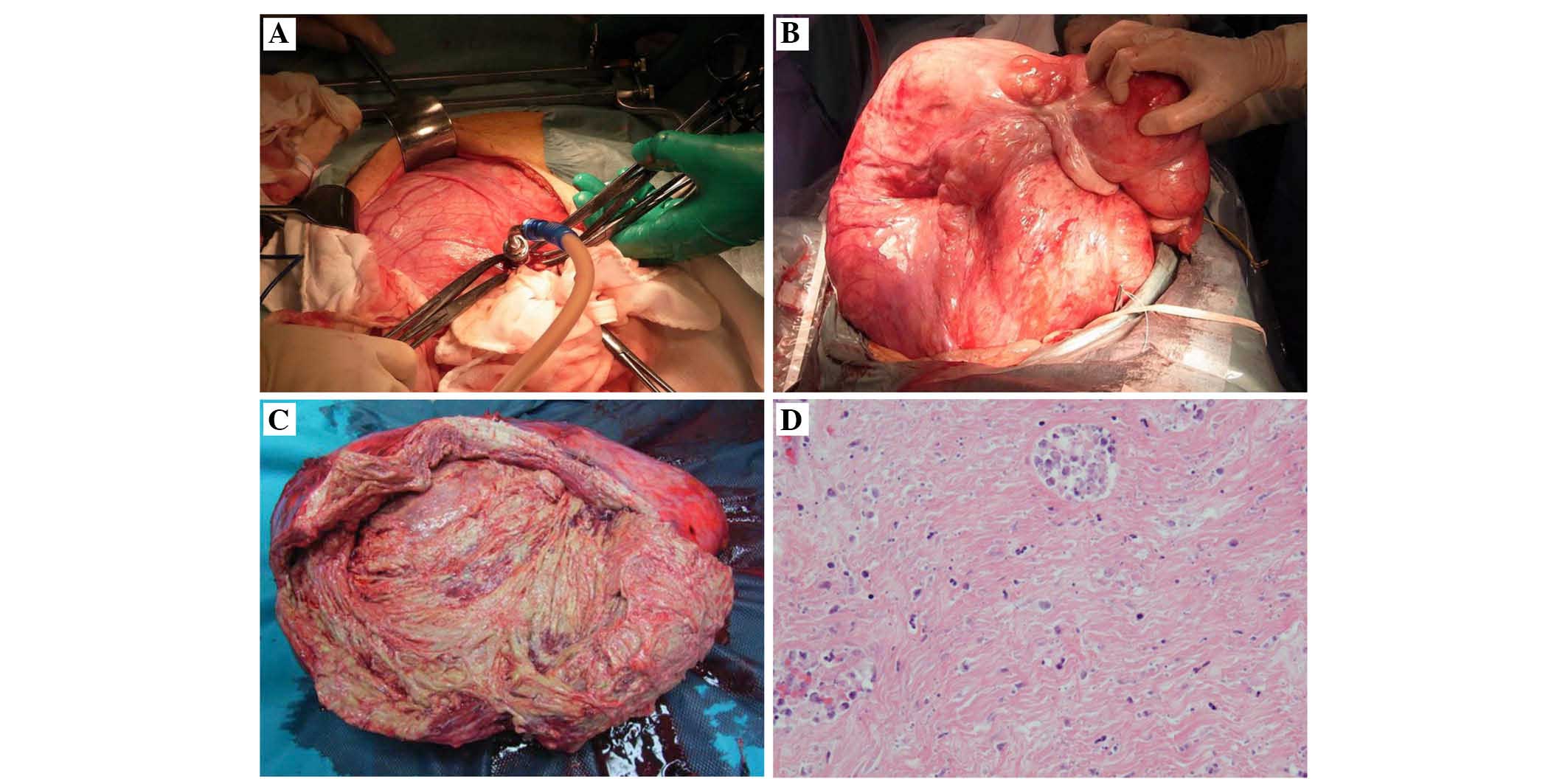

pre-operatively. Intraoperative findings demonstrated a solid tumor

arising from the back of the uterine body with normal bilateral

adnexa. Prior to removal, 12.4 liters of purulent, malodorous fluid

was drained from the tumor (Fig. 2A and

B). The resected mass was 50×37×20 cm in size and 13.5 kg in

weight. The surrounding myometrium appeared normal and measured 3

cm in thickness, and the cut surface of the mass was

purple-yellowish (Fig. 2C). Cultures

of the pus in the tumor revealed the presence of Streptococcus

agalactiae. An IUD was identified near the cervix, however

culture was negative. The pathological diagnosis was leiomyoma with

marked necrosis and chronic inflammation, with no evidence of

malignancy (Fig. 2D). Following

resection of the tumor, the patient's weight decreased to 55 kg.

The post-operative course was uneventful and the patient was

discharged from the hospital on post-operative day 14. At 4 months

follow-up, the patient's weight had increased to 62 kg due to a

good appetite.

Discussion

Pyomyoma occurs in both post-and pre-menopausal

women, however, the risk of suppurative myoma is increased by

pregnancy (1,2). For post-menopausal patients, systemic

vascular changes have been suggested to be the likely underlying

cause of pyomyoma (6). Necrosis of

the leiomyoma caused by vascular flow insufficiency in the uterus

following menopause is also a possible cause. A history of uterine

leiomyoma, pregnancy, abortion, menopause, uterine artery

embolization (UAE), IUD, vascular insufficiency (diabetes,

hypertension and atherosclerosis) and systemic disease or infection

may be predisposing factors for pyomyoma; however, definitive

diagnoses remain difficult. Although rapid clinical diagnosis for

pyomyoma is often difficult due to its low incidence and the

requirement to rule out the possibility of malignancy, mortality

has decreased due to the improvement in surgical treatments,

including myomectomy and hysterectomy, and broad-spectrum

antibiotics.

A MEDLINE search since 1945 revealed only 50

reported cases of pyomyoma: 27 were non-pregnant woman (mean age,

51.8 years; range, 36–69-years-old; Table I) (3–29) and 23

cases were associated with pregnancy or abortion (mean age, 33.6

years; range, 28–44-years-old). The mean pyomyoma size in

non-pregnancy and pregnancy-associated cases were 16.2 cm (3–38 cm)

and 13.5 cm (5–58 cm), respectively. Non-pregnancy pyomyoma tended

to be larger compared with pregnancy-associated pyomyoma, and the

present case was the largest among all reported cases of

non-pregnancy-associated pyomyoma. Severe anemia gravis and

inflammatory reaction were described in numerous pyomyoma cases,

including the present study. The presentation and complications of

pyomyoma vary. It has been shown that 2/50 cases had a history of

IUD usage (7,30), 5/50 cases had UAE (8–12), 6/50

cases had vascular insufficiency (4,13–17) and

8/50 cases demonstrated gas production (6,8–10,12,31–33).

Notably, gas production was observed in 4/5 UAE cases (8–10,12).

Although pyomyoma arises spontaneously, post-partum,

post-instrumentation or post-surgery have been reported in the

literature, only two cases include a IUD, and only one case has

been previously reported in a non-pregnant woman (7). Knowledge of IUD history may be helpful

in the diagnosis of pyomyoma.

| Table I.Previously reported cases of pyomyoma

without pregnancy, since 1945. |

Table I.

Previously reported cases of pyomyoma

without pregnancy, since 1945.

| Author, year | Age | Key points | Laboratory data | Size |

Treatmenta | Refs. |

|---|

| Miller et al,

1945 | 51 | STM | WBC 38,700/µl | 35×25 cm | Subtotal hysterectomy

+ BSO | (3) |

| Kaufmann et

al, 1974 | 58 | STM, HT, DM | WBC 28,800/µl, Hb 7.3

g/dl | ns | No treatment | (4) |

| Greenspoon et

al, 1990 | 49 | STM | WBC 21,200/µl, Hb 7.4

g/dl | 11.5×9×11 cm, 2.5

kg | No treatment | (5) |

| Chen et al,

2014 | 67 | Gas production | WBC 12,300/µl, CA125

29.98 U/ml | 25×20×15 cm | TAH + BSO | (6) |

| Manchana et

al, 2007 | 42 | IUD | WBC 29,380/µl, Hb 8.7

g/dl, CA125 65.2 U/ml | 15×15 cm | TAH + BSO | (8) |

| Kitamura et

al, 2005 | ns | UAE, gas

production | ns | ns | TAH | (9) |

| Abulafia et

al, 2010 | 48 | UAE, gas

production | WBC 22,600/µl, Hb 8.1

g/dl | 11×10×6 cm | TAH | (10) |

| Shukla et al,

2012 | 65 | UAE, gas

production | WBC 7,900/µl | 12×10 cm | TAH + BSO | (11) |

| Pinto et al,

2012 | 36 | UAE | WBC normal, Hb 9.5

g/dl | 6.8×5.6×5.5 cm | Laparoscopic

drainage | (12) |

| Rosen et al,

2013 | 47 | UAE, gas

production | WBC 15,900/µl | ns | Supracervical

hysterectomy + RSO | (13) |

| Weiss et al,

1976 | 59 | DM | ns | 15 cm | TAH + BSO | (14) |

| Genta et al,

2001 | 60 | DM, DVT | WBC 14,100/µl, Hb 7.7

g/dl, CA125 109.7 U/ml | 25×20 cm | TAH + BSO +

omentectomy | (15) |

| Fletcher et

al, 2009 | 44 | DM | WBC 22,500/µl, Hb 7.8

g/dl, CA125 17.5 U/ml | 15.5×16×9 cm | TAH + BSO | (16) |

| Ono et al,

2014 | 69 | DM | WBC 10,710/µl, CRP

2.71 mg/dl, Hb 7.6 g/dl | ns | TAH | (17) |

| Goyal et al,

2015 | 42 | DM | WBC 10,200/µl, Hb

9.5 g/dl | 6 cm | Subtotal

hysterectomy + | (18) |

| Lee et al,

2010 | 46 | FDG-PET | WBC 10,100/µl, Hb

8.8 g/dl, CA125 59.2 U/ml | 38×30×10 cm, 3

kg | LSO +TAH | (22) |

| Bedrosin et

al, 1956 | 50 | N/A | WBC 12,800/µl, Hb

11.0 g/dl | 7 cm | TAH + BSO | (23) |

| Fuller et

al, 1985 | 68 | N/A | WBC 24,000/µl | 10 cm | TAH + BSO | (24) |

| Yang and Wang,

1999 | 46 | N/A | WBC 45,400/µl, Hb

7.0 g/dl | 13×12 cm | TAH + BSO | (25) |

| Gupta et al,

1999 | 60 | N/A | WBC 14,000/µl | 30×25 cm, 4.3

kg | TAH + BSO | (26) |

| Sah et al,

2005 | 64 | N/A | WBC 15,000/µl, Hb

8.0 g/dl | 22×23×10 cm, 3.5

kg | TAH + BSO | (27) |

| Yeat et al,

2005 | 53 | N/A | WBC 52,600/µl, CRP

42.4 mg/dl, Hb 8.6 g/dl | 12×12×10 cm, 1,020

g | TAH + BSO | (28) |

| Patwardhan and

Bulmer, 2007 | 38 | N/A | WBC 18,500/µl, CRP

22.5 mg/dl | ns | Myomectomy | (29) |

| Chen et al,

2010 | 46 | N/A | WBC 13,000/µl, Hb

7.9 g/dl | 14.3×12×8 cm | TAH | (30) |

| Kuriyama et

al, 2010 | 51 | N/A | WBC 15,900/µl, CRP

13.1 mg/dl | ns | TAH | (31) |

| Zangeneh et

al, 2010 | 47 | N/A | WBC normal, Hb 10.3

g/dl | 3×5 cm | TAH + BSO | (32) |

| Liu and Chen,

2011 | 42 | N/A | WBC 42,880/µl | 9.0×8.0×6.5 cm | Open drainage | (33) |

| Present report | 53 | IUD | WBC 57,300/µl, CRP

20.24 mg/dl, Hb 5.7g/dl, CA125 200.2 U/ml | 50×37×20 cm, 13.5

kg | TAH + BSO | – |

Pyomyoma was often associated with polymicrobial

infection. Among the 50 reported cases, infection by

Staphylococcus species was reported in 8 cases,

Streptococcus species in 7 cases, Escherichia coli in

6 cases, Enterococcus faecalis in 5 cases,

Clostridium species in 3 cases, Proteus species in 2

cases and Candida species in 2 cases. In the present case,

Streptococcus agalactiae was cultured from the pus and

tumor, however, not from the blood and vagina, suggesting the

infection existed focally within the tumor. Therefore, conservative

management with pre-operative broad-spectrum antibiotics and

appropriate surgery was performed successfully. For surgical

treatment, hysterectomy was performed in 32 cases, myomectomy in 10

cases and drainage in 6 cases.

Diagnosis of large pyomyoma is difficult since

surgery is required for a definitive diagnosis. A malignant tumor,

in particular ovarian cancer, was initially suspected due to the

findings of a large abdominal mass with signs of necrosis in a

cachexic perimenopausal woman with an elevated CA125 level. In a

previous report, imaging analysis was shown to identify only

non-specific results (6). MRI and

positron emission tomography did not improve the specificity of

pyomyoma diagnosis. Although intratumoral gas formation is markedly

suggestive of pyomyoma on ultrasound and CT imaging, gas formation

is not consistently observed, as with the present case. In the

present case, contrast CT contributed to the diagnosis of pyomyoma

due to the identification of the uterine artery location.

CA125 has been observed to be increased in other

gynecologic and non-gynecologic malignancies, as well as in a

variety of benign disorders, including leiomyoma. Among the

previously reported cases of pyomyoma, 5 cases reported CA125

levels (6,7,14,15,18),

with a mean level of 56.3 U/ml (29.98–109.7 U/ml). CA125 was

measured only in non-pregnancy-associated cases, possibly due to

suspicion of gynecological malignancy based on the age of the

patient and size of tumor. Furthermore, in pregnancy-associated

cases, diagnosis of myoma was likely during pre-natal examination

prior to the onset of the symptom, which may have contributed to

the identification of the tumor origin. In the present case, CA125

level was the highest compared with the previously reported

cases.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the third

IUD-associated case of pyomyoma, with the largest tumor size and

highest CA125 level compared with previously reported non-pregnancy

cases. A large pyomyoma is difficult to distinguish from a

gynecological malignant tumor, particularly in perimenopausal,

cachectic women with non-specific clinical presentation and without

a history of leiomyoma. A history of IUD usage and contrast CT may

be helpful in the diagnosis of pyomyoma. Gynecologists and general

surgeons must be aware of the possibility of pyomyoma when

presented with a large abdominal tumor, and in certain cases,

surgery in combination with broad spectrum antibiotics may result

in a good outcome.

References

|

1

|

Mason TC, Adair J and Lee YC: Postpartum

pyomyoma. J Natl Med Assoc. 97:826–828. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kobayashi F, Kondoh E, Hamanishi J,

Kawamura Y, Tatsumi K and Konishi I: Pyomayoma during pregnancy: A

case report and review of the literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res.

39:383–389. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Miller I: Suppurating fibromyomas. Report

of a case with a review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol.

50:522–526. 1945.

|

|

4

|

Kaufmann BN, Cooper VM and Cookson P:

Clostridium perfringens septicemia complicating degenerating

uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 118:877–878. 1974.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Greenspoon JS, Ault M, James BA and Kaplan

L: Pyomyoma associated with polymicrobial bacteremia and fatal

septic shock: Case report and review of the literature. Obstet

Gynecol Surv. 45:563–569. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Chen JR, Yang TL, Lan FH and Lin TW:

Pyomyoma mimicking advanced ovarian cancer: A rare manifestation in

a postmenopausal virgin. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 53:101–103. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Manchana T, Sirisabya N, Triratanachat S,

Niruthisard S and Tannirandorn Y: Pyomyoma in a perimenopausal

woman with intrauterine device. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 63:170–172.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kitamura Y, Ascher SM, Cooper C, Allison

SJ, Jha RC, Flick PA and Spies JB: Imaging manifestations of

complications associated with uterine artery embolization.

Radiographics. 25:(Suppl 1). S119–S132. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Abulafia O, Shah T, Salame G, Miller MJ,

Serur E, Zinn HL, Sokolovski M and Sherer DM: Sonographic features

associated with post-uterine artery embolization pyomyoma. J

Ultrasound Med. 29:839–842. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shukla PA, Kumar A, Klyde D and Contractor

S: Pyomyoma after uterine artery embolization. J Vasc Interv

Radiol. 23:423–424. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pinto E, Trovão A, Leitão S, Pina C, Mak

Fk and Lanhoso A: Conservative laparoscopic approach to a

perforated pyomyoma after uterine artery embolization. J Minim

Invasive Gynecol. 19:775–779. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rosen ML, Anderson ML and Hawkins SM:

Pyomyoma after uterine artery embolization. Obstet Gynecol. 121:(2

Pt 2 Suppl 1). S431–S433. 2013.

|

|

13

|

Weiss G, Shenker L and Gorstein F:

Suppurating myoma with spontaneous drainage through abdominal wall.

N Y State J Med. 76:572–573. 1976.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Genta PR, Dias ML, Janiszewski TA,

Carvalho JP, Arai MH and Meireles LP: Streptococcus agalactiae

endocarditis and giant pyomyoma stimulating ovarian cancer. South

Med J. 94:508–511. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Fletcher H, Gibson R, Williams N, Wharfe

G, Nicholson A and Soares D: A woman with diabetes presenting with

pyomyoma and treated with subtotal hysterectomy: A case report. J

Med Case Rep. 3:74392009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ono H, Kanematsu M, Kato H, Toyoki H,

Hayasaki Y, Furui T, Morishige K and Hatano Y: MR imaging findings

of uterine pyomyoma: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Abdom

Imaging. 39:797–801. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Goyal S, Mohan H, Punia RS and Tandon R:

Subserosal pyomyoma and tubo-ovarian abscess in a diabetic patient.

J Obstet Gynaecol. 35:101–102. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lee SR, Kim BS and Moon HS: Magnetic

resonance imaging and positron emission tomography of a giant

multiseptated pyomyoma simulating an ovarian cancer. Fertil Steril.

94:1900–1902. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Bedrosian L, Gabriels AG Jr and Hengerer

AD: Ruptured suppurating myoma; a surgical emergency. Am J Obstet

Gynecol. 71:1145–1147. 1956. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Fuller AF Jr and Lawrence WD: Case records

of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 23-1985. N Engl J Med.

312:1505–1511. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Yang CH and Wang CK: Edwardsiella tarda

bacteraemia-complicated by acute pancreatitis and pyomyoma. J

Infect. 38:124–126. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gupta B, Sehgal A, Kaur R and Malhotra S:

Pyomyoma: A case report. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynecol. 39:520–521.

1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Sah SP, Rayamajhi AK and Bhadani PP:

Pyomyoma in a postmenopausal woman: A case report. Southeast Asian

J Trop Med Public Health. 36:979–981. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Yeat SK, Chong KM, Pan HS, Cheng WC, Hwang

JL and Lee CC: Impending sepsis due to a ruptured pyomyoma with

purulent peritonitis: A case report and literature review. Taiwan J

Obstet Gynecol. 44:75–79. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Patwardhan A and Bulmer P: Pyomyoma as a

complication of uterine fibroids. J Obstet Gynaecol. 27:444–445.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chen ZH, Tsai HD and Sun MJ: Pyomyoma: A

rare and life-threatening complication of uterine leiomyoma. Taiwan

J Obstet Gynecol. 49:351–356. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kuriyama K, Makiishi T, Maeda S, Konishi T

and Hirose K: Acute bilateral renal cortical necrosis complicating

pyomyoma. Intern Med. 49:511–512. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zangeneh M, Alsadat Mahdavi A, Amini E,

Davar Siadat S and Karimian L: Pyomyoma in a premenopausal woman

with fever of unknown origin. Obstet Gynecol. 116:(Suppl 2).

S526–S528. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Liu HS and Chen CH: Subserosal pyomyoma in

a virgin female: Sonographic and computed tomographic imaging

features. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 37:247–248. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Wong TC, Bard DS and Pearce LW: Unusual

case of IUD associated postabortal sepsis complicated by an

infected necrotic leiomyoma, suppurative pelvic thrombophlebitis,

ovarian vein thrombosis, hematoperitoneum and drug fever. J Ark Med

Soc. 83:138–147. 1986.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Karcaaltincaba M and Sudakoff GS: CT of a

ruptured pyomyoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 181:1375–1377. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Nguyen QH and Gruenewald SM: Sonographic

appearance of a postpartum pyomyoma with gas production. J Clin

Ultrasound. 36:186–188. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Stroumsa D, Ben-David E, Hiller N and

Hochner-Celnikier D: Severe clostridial pyomyoma following an

abortion does not always require surgical intervention. Case Rep

Obstet Gynecol. 2011:3646412011.PubMed/NCBI

|