Introduction

Since anaplastic pancreatic carcinoma (ANPC) is rare

and accounts for only 2–7% of all pancreatic carcinoma cases, its

clinical features and surgical outcomes remain to be elucidated

(1,2).

A total of three pathological subtypes of ANPC exist: Spindle cell

carcinoma, giant cell carcinoma, and pleomorphic carcinoma.

Surgical resection is the only curative therapy for patients with

ANPC since no effective systemic chemotherapy or other

interventions are available; however, long-term survival remains to

be achieved in patients with ANPC even following curative surgery

(1,3).

ANPC is often associated with a delay in clinical presentation as a

result of its asymptomatic nature until the tumor has progressed to

an advanced stage. In several reports that have been published

since the early 1900s, ANPC was referred to as ‘giant-cell tumor’,

‘undifferentiated carcinoma’ with or without osteoclast-like giant

cells and ‘pleomorphic carcinoma’ of the pancreas (3–6).

Establishing the precise pre-operative diagnosis is

difficult due to the radiological findings being atypical and

similar to those of gastrointestinal stromal tumors, mucinous cyst

adenocarcinomas and pancreatic carcinomas. Upon admission, the

present patient's tumor was already huge and revealed enhanced rims

with hypodense lesions on computed tomography (CT) scans, which

appears to be a common radiological feature of ANPCs (1).

Of the three subtypes, spindle cell carcinoma is the

most aggressive subtype of sarcomatoid carcinoma and currently no

effective systemic chemotherapies or other interventions are

available. According to previous reports, two patients with ANPC

with rhabdoid features had dismal prognoses following surgical

intervention (7,8). The present study described a case of

spindle cell ANPC that exhibited aggressive growth following

emergency curative surgery.

Case report

A 74-year-old woman without any previous medical

history was admitted to our hospital in April 2015. Physical

examination revealed a firm tumor located in her left upper

quadrant. Abdominal ultrasonography detected a giant cystic tumor

containing high and low echoic lesions in the body and tail of the

pancreas. Admission laboratory tests revealed that the serum levels

of carbohydrate antigen 19-9, carcinoembryonic antigen and DUPAN-2

were elevated (78.0, 36.6 and 1,200 U/ml, respectively). On

contrast-enhanced CT scanning, the tumor occupying the left upper

and lower abdomen was measured to be 9.5×8.0 cm. This tumor

consisted of multilocular cystic components, both the rim and core

of the tumor were strongly enhanced on the arterial phase CT images

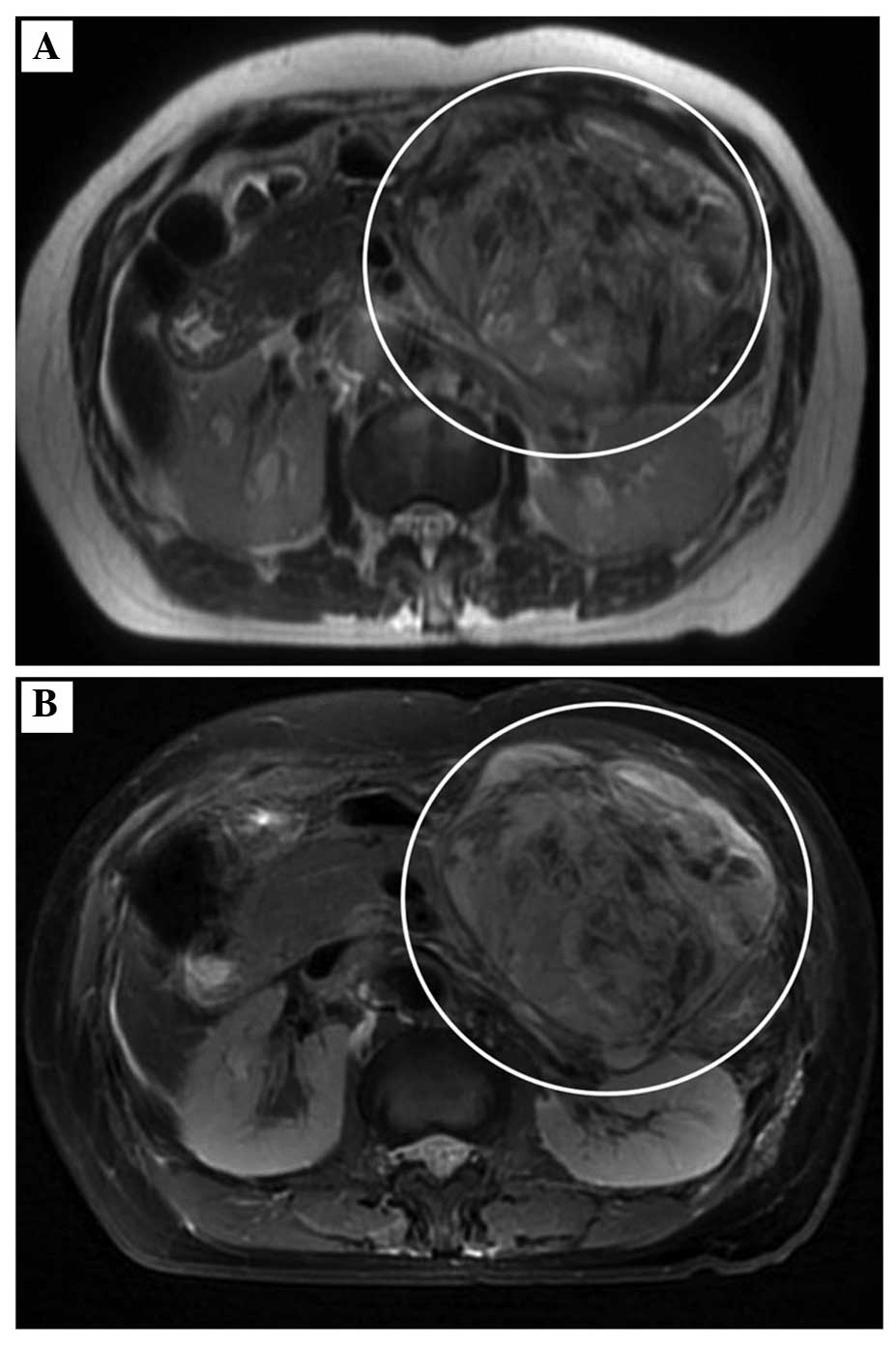

(Fig. 1). A dilatation of the distal

main pancreatic duct was evident, however, no distant metastases,

lymph node swelling or ascites were detected. The solid tumor

exhibited low signal intensity on T1-weighted magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) and relatively high signal intensity on T2-weighted

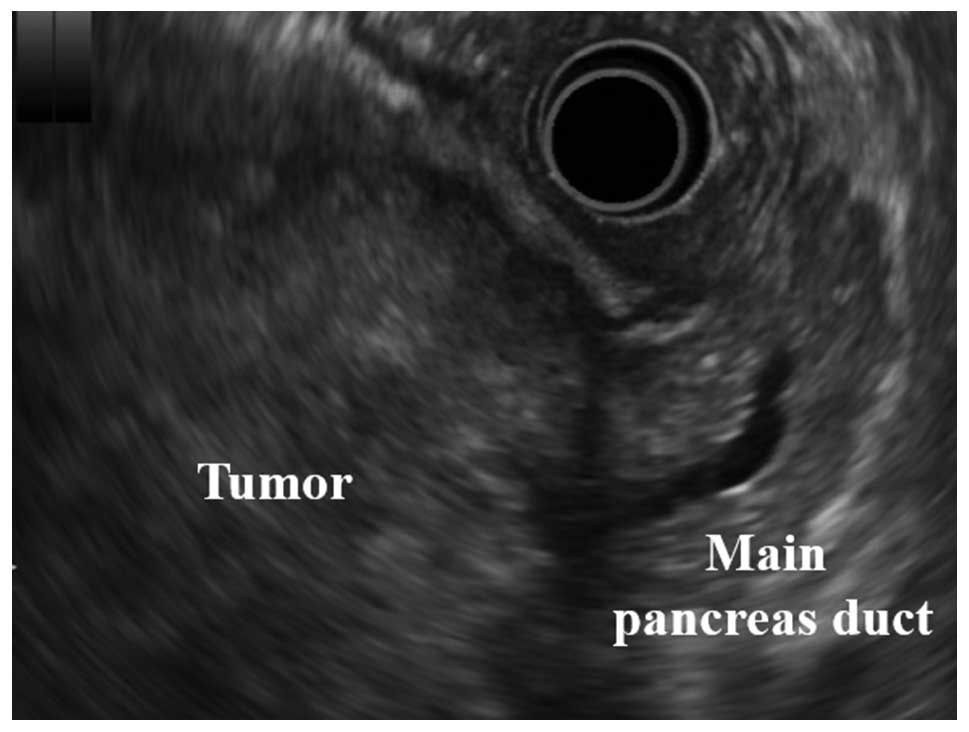

MRI (Fig. 2). Intraductal

ultrasonography demonstrated a huge solid tumor derived from the

body of the pancreas and located within a clear margin from the

stomach (Fig. 3).

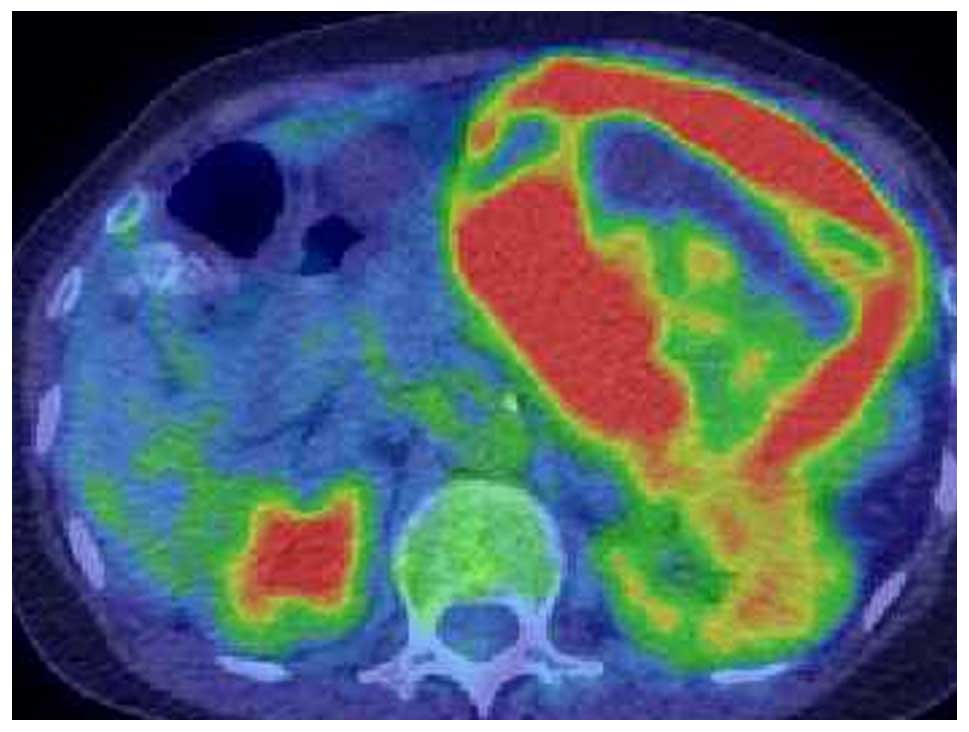

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission

tomography/CT identified no distant metastasis, and FDG

accumulation was detected only in the tumor lesion (Fig. 4). The differential diagnoses were

pancreatic adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor,

endocrine cell carcinoma or solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the

pancreas. At 3 weeks after the initial admission of the patient,

massive ascites suddenly emerged and the tumor increased in from a

size of 9.5 cm to 11 cm in the maximal diameter. The patient

experienced an increase in acute abdominal pain, which was

uncontrollable by analgesic medications. During an emergency

laparotomy, bloody ascites of 1,700 ml was observed; however,

peritoneal dissemination or liver metastasis was not detected. A

distal pancreatectomy and a splenectomy with regional lymph node

dissection were performed. The operation lasted 4 h 13 min. Blood

loss during the operation was 1,300 ml and the bloody ascites

volume was 1,700 ml.

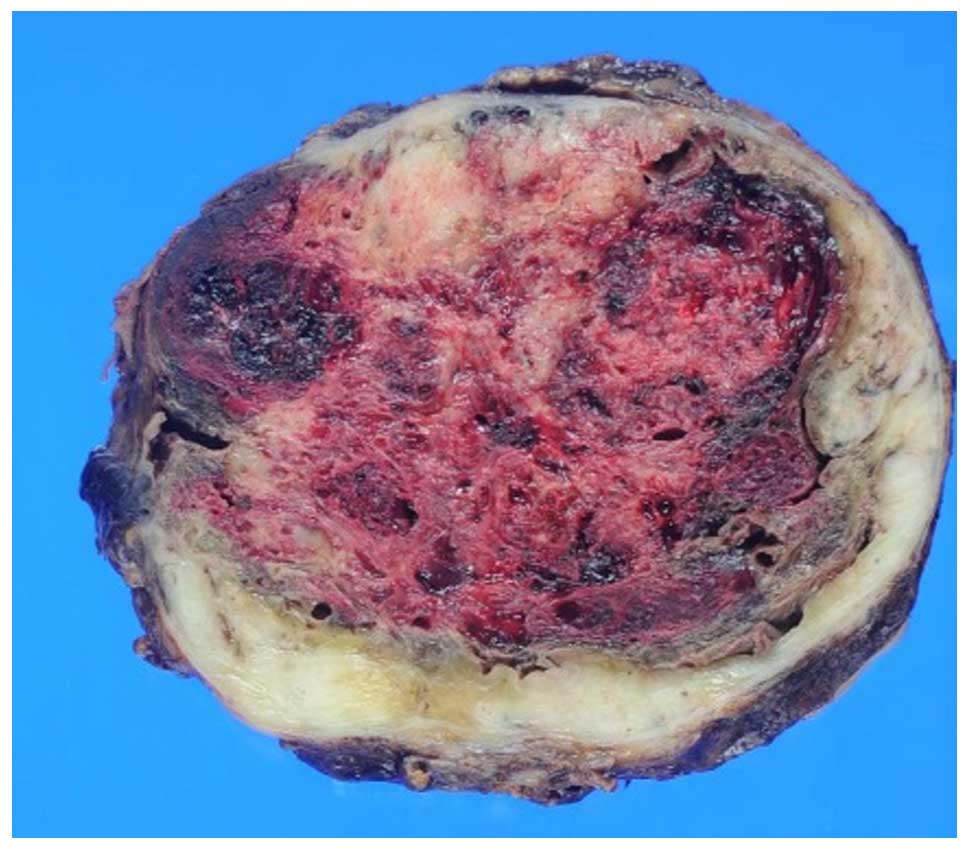

On macroscopic observation, the tumor was 11×12 cm,

and its appearance was elastic, hard and a white mass (Fig. 5). All specimens were processed in a

routine manner for paraffin embedding and 5 µm-thick sections were

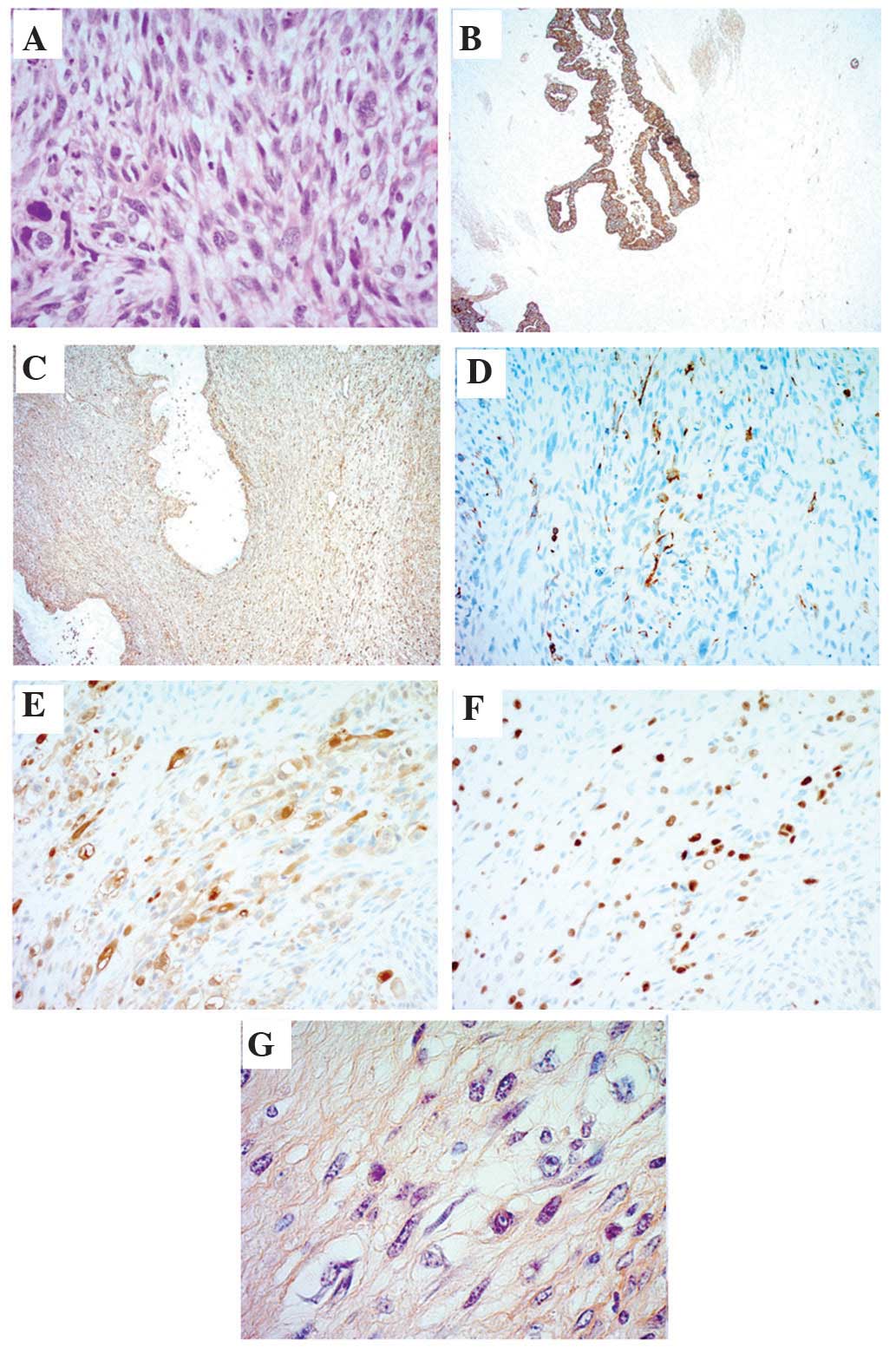

cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Histopathological

analysis of the sections revealed that the tumor cells had acquired

dedifferentiated rhabdoid features and were positive for

phosphotungstic acid-hematoxylin. Additionally, the tumor cells

were positive for phosphotungstic acid-hematoxylin (PTAH) stain,

myoglobin (cat. no. H0309; Nichilei Biosciences, Inc., Tokyo,

Japan), myogenin (F5D; cat. no. 1328706B; Dako, Carpinteria, CA,

USA), vimentin (V9; cat. no. H1402; Dako) and cytokeratin 5.2

(CAM52; cat. no. D04930; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA;

Fig. 6). Therefore, a diagnosis of

spindle cell ANPC with rhabdoid features was made based on the

pathological findings. The patient was discharged 14 days

post-operation without any complications. The patient succumbed to

mortality 8 months following the surgery while undergoing systemic

adjuvant chemotherapy.

Discussion

Spindle cell ANPC has been reported to have the

worst prognosis of the three ANPC subtypes (3). The presence of rhabdoid features in ANPC

is extremely rare; only two such cases have been reported to date

(7,8).

ANPC accounts for 2–7% of all pancreatic carcinoma cases. The

present case exhibited an atypical clinical presentation and

radiological findings, which allowed the present study to

distinguish ANPC from gastrointestinal stromal tumor, solitary

pseudopapillary neoplasms and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (1). Rapid tumor progression associated with

massive ascites and uncontrollable abdominal pain occurred in the

present case. Distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy were

successfully performed to excise the giant tumor. Establishing the

precise diagnosis was difficult due to the atypical radiological

findings and tumor rarity. Although a huge tumor of the pancreas

can be treated via surgical resection, the prognosis is poor even

following surgery. Whenever possible, radical resection is

recommended.

Although multiple case reports on ANPC have been

published, the clinical presentation and surgical outcomes remain

to be well investigated owing to the rarity of this disease

(3,9–12). Upon

admission of the patient, the radiological findings on

contrast-enhanced CT was a huge tumor with a well-enhanced rim and

hypodense areas in the center. On T1-weighted MRI, the tumor

exhibited a low signal intensity, however, on T2-weighted MRI, the

intensity of the signal was high.

Strobel et al (1) reported that ANPC is an aggressive type

of pancreatic cancer with a dismal prognosis (1). Whenever possible, resection must be

attempted, as it is the only treatment associated with a favorable

prognosis. Although the clinical presentation and radiological

findings are similar to those of pancreatic carcinoma, despite the

lack of a precise diagnosis, curative surgery, whenever possible,

must not be postponed. According to previous reports, obtaining

pre-operative tissue samples does not change the therapeutic

approach and is not advisable if the neoplasm appears

resectable.

Neither an effective chemotherapy nor a standard

regimen has been established for ANPC. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was

reported to be effective in one case, however, a standard regimen

was not established (13). Wakatsuki

et al (12) reported that a

complete response was achieved following treatment with paclitaxel

(PTX) (12). The present patient was

treated with a nab-PTX and gemcitabine regimen, which failed to

prevent multiple live metastases and peritoneal disseminations.

PTX, a microtubule-stabilizing agent, has proven effective in

treating several types of cancer, including breast, lung and

ovarian. PTX exerts a particularly strong antitumor activity

against certain types of sarcomas including angiosarcoma, Kaposi

sarcoma and carcinosarcoma of the uterus and heart (14–16).

Strobel et al (1) compared clinical features and surgical

outcomes of ANPC and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. In the ANPC

group, the duration of survival was significantly greater following

R0/R1 resection compared with after palliative treatment. On the

basis of the results of the previous study, the authors recommend

that patients with ANPC be operated on whenever a potentially

curative resection is possible since established systemic

chemotherapy or alternative therapy is available. Among the several

subtypes of ANPC, the spindle cell type exhibited the worst

prognosis even following curative surgery; the prognosis was

particularly poor in the present case of ANPC associated with

rhabdoid features.

Immunohistochemistry revealed that the present

patient's tumor was positive for cytokeratin 5.2, vimentin, desmin,

myoglobin, myogenin and PTAH. Kane et al (3) reviewed the immunohistochemistry results

of sarcomatoid components from previous reports and their results

are consistent with the present positive findings for desmin,

vimentin and myogenin (3). Notably,

PTAH positivity, which represents cell dedifferentiation into

striated muscle, was detected only in the present case. These

phenotypic changes suggested that the epithelial cancer cells had

transformed into mesenchymal cancer cells. The mechanism of such a

transformation may be owing to the presence of cancer stem cells or

the dedifferentiation of tumor cells into sarcoma cells.

In conclusion, ANPC is a rare and aggressive variant

of pancreatic cancer. Spindle cell ANPC is associated with a

particularly dismal prognosis. The only typical radiological

feature of ANPC is a large tumor with an enhanced rim and a

hypodense area in the center. As surgical resection is the only

intervention that results in long-term survival in patients with

ANPC, it must be attempted whenever possible. Further studies are

required to clarify the mechanism of the aggressiveness of this

type of cancer.

References

|

1

|

Strobel O, Hartwig W, Bergmann F, Hinz U,

Hackert T, Grenacher L, Schneider L, Fritz S, Gaida MM, Büchler MW

and Werner J: Anaplastic pancreatic cancer: Presentation, surgical

management, and outcome. Surgery. 149:200–208. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hoorens A, Prenzel K, Lemoine NR and

Klöppel G: Undifferentiated carcinoma of the pancreas: Analysis of

intermediate filament profile and Ki-ras mutations provides

evidence of a ductal origin. J Pathol. 185:53–60. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kane JR, Laskin WB, Matkowskyj KA, Villa C

and Yeldandi AV: Sarcomatoid (spindle cell) carcinoma of the

pancreas: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett.

7:245–249. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Fabre J, Planques J, Bouissou H and

Sendrail-Pesque M: Sarcomatoid carcinoma of the pancreas. Toulouse

Med. 62:85–98. 1961.(In French). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Alguacil-Garcia A and Weiland LH: The

histologic spectrum, prognosis, and histogenesis of the sarcomatoid

carcinoma of the pancreas. Cancer. 39:1181–1189. 1977. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Ackerman NB, Aust JC, Bredenberg CE,

Hanson VA Jr and Rogers LS: Problems in differentiating between

pancreatic lymphoma and anaplastic carcinoma and their management.

Ann Surg. 184:705–708. 1976. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Kuroda N, Iwamura S, Fujishima N, Ohara M,

Hirouchi T, Mizuno K, Hayashi Y and Lee GH: Anaplastic carcinoma of

the pancreas with rhabdoid features and hyaline globule-like

structures. Med Mol Morphol. 40:168–171. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kuroda N, Sawada T, Miyazaki E, Hayashi Y,

Toi M, Naruse K, Fukui T, Nakayama H, Hiroi M, Taguchi H and Enzan

H: Anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas with rhabdoid features.

Pathol Int. 50:57–62. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Sano M, Homma T, Hayashi E, Noda H, Amano

Y, Tsujimura R, Yamada T, Quattrochi B and Nemoto N:

Clinicopathological characteristics of anaplastic carcinoma of the

pancreas with rhabdoid features. Virchows Arch. 465:531–538. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Okazaki M, Makino I, Kitagawa H, Nakanuma

S, Hayashi H, Nakagawara H, Miyashita T, Tajima H, Takamura H and

Ohta T: A case report of anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas with

remarkable intraductal tumor growth into the main pancreatic duct.

World J Gastroenterol. 20:852–856. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fujiogi M, Kobayashi T, Yasuno M and

Tanaka M: Anaplastic carcinoma of the pancreas mimicking submucosal

gastric tumor: A case report of a rare tumor. Case Rep Med.

2013:5232372013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Wakatsuki T, Irisawa A, Imamura H,

Terashima M, Shibukawa G, Takagi T, Takahashi Y, Sato A, Sato M,

Ikeda T, et al: Complete response of anaplastic pancreatic

carcinoma to paclitaxel treatment selected by chemosensitivity

testing. Int J Clin Oncol. 15:310–313. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Jones TS, Jones EL, McManus M, Shah R and

Gajdos C: Multifocal anaplastic pancreatic carcinoma requiring

neoadjuvant chemotherapy and total pancreatectomy: Report of a

case. JOP. 14:289–291. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Otsuki A, Watanabe Y, Nomura H, Futagami

M, Yokoyama Y, Shibata K, Kamoi S, Arakawa A, Nishiyama H, Katsuta

T, et al: Paclitaxel and carboplatin in patients with completely or

optimally resected carcinosarcoma of the uterus: A phase II trial

by the Japanese uterine sarcoma group and the tohoku gynecologic

cancer unit. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 25:92–97. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Brambilla L, Romanelli A, Bellinvia M,

Ferrucci S, Vinci M, Boneschi V, Miedico A and Tedeschi L: Weekly

paclitaxel for advanced aggressive classic Kaposi sarcoma:

Experience in 17 cases. Br J Dermatol. 158:1339–1344. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ram Prabu MP, Thulkar S, Ray R and Bakhshi

S: Primary cardiac angiosarcoma with good response to Paclitaxel. J

Thorac Oncol. 6:1778–1779. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|