Introduction

In 2017, six molecular targeted agents were approved

for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) in

Japan (1). Results of large-scale

clinical trials (2–7), as well as from our institution

(8), and other investigators in

Japan (9–12) have reported real-world clinical data

showing an improvement in the survival rate of patients with mRCC.

However, it is uncertain for which type of patient will this

treatment be effective. Differences in survival rates according to

the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) criteria

(13) and the International

Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) model

(14) are being studied. Motzer

et al reported that Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

performance status, serum hemoglobin level, time from diagnosis to

treatment, and corrected calcium, alkaline phosphatase, and lactate

dehydrogenase levels were significant independent predictors for

survival (15). It was also reported

that the prognostic factors used in the MSKCC classification are

robust and applicable in the contemporary era of targeted therapy.

Although these models correlated well with cancer survival, only a

few reports presented the survival rate as classified by metastatic

organ. In the cytokine therapy era, there was minimal variation in

the metastatic organ among Japanese patients (16,17).

Liver, bone, lymph node, and brain metastases were independent risk

factors for mRCC due to interferon-α administration. However, the

relationship between metastatic organ and mRCC treatment using

molecular targeted drugs (10,18,19) are

not well studied. Therefore, we aimed to investigate the survival

rate classified according to the metastatic lesion in the molecular

targeted agents era for mRCC in Japanese patients.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively analyzed 180 consecutively

treated patients who had received molecular targeted drugs for

mRCC. Regarding administration of first-line drugs, sunitinib 50 mg

was administered orally (PO) every day over 2 or 4 weeks, followed

by a 1- or 2-week washout period. Dose reductions, if needed, were

made in decrements of 12.5 mg. Sorafenib was administered

continuously at a full dose of 400 mg PO twice a day, with an

allowed dose reduction of 200 mg (2,3).

Temsirolimus was administered at a full dose of 25 mg div weekly

(7). For second-line drugs,

everolimus was administered continuously at a full dose of 10 mg PO

per day (4). Axitinib was

administered continuously at a full dose of 10 mg PO per day, with

allowed dose escalation of up to 20 mg, and dose reduction of up to

2 mg (20). According to the

therapeutic strategy in our institute, sorafenib is used as the

first-line therapy and sunitinib or everolimus as the second-line

therapy. From 2010 onward, we usually used sunitinib as the

first-line therapy, and from 2012 onward, we usually used axitinib

as the second-line therapy.

We calculated the overall survival (OS), OS

classified according to the MSKCC criteria (21), the number of metastatic organs, the

metastatic lesion, and presence or absence of nephrectomy. OS

period commenced from treatment with the initial targeted therapy.

OS was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the differences

were determined using the log-rank test. Cox proportional stepwise

multivariate analysis was used to evaluate the association between

the number of metastatic organ, metastatic site, MSKCC criteria,

presence or absence of nephrectomy and OS.

Response assessment was performed by using computed

tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans every 10–12 weeks,

and evaluated according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in

Solid Tumors (RECIST) v.1.1, and the change in the pancreatic tumor

size was calculated by the fraction of decrease or increase in the

sum of the largest diameter of the target lesions (22). A P-value <0.05 was considered

statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed

using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington,

USA). Permission to access the database for review of the medical

records of these patients was approved by the Local Research Ethics

Committee at Osaka City University (approval number 3441).

Results

The median age of the patients was 67 years (range:

35–84) Other patient characteristics and treatments are shown in

Table I. Patients belonging to the

intermediate risk class accounted for about 50% of all risk

classes. The number of metastatic organs was almost evenly

allocated to single or multiple. Lungs were the most common

metastatic organ, followed by lymph nodes and bone. The median OS

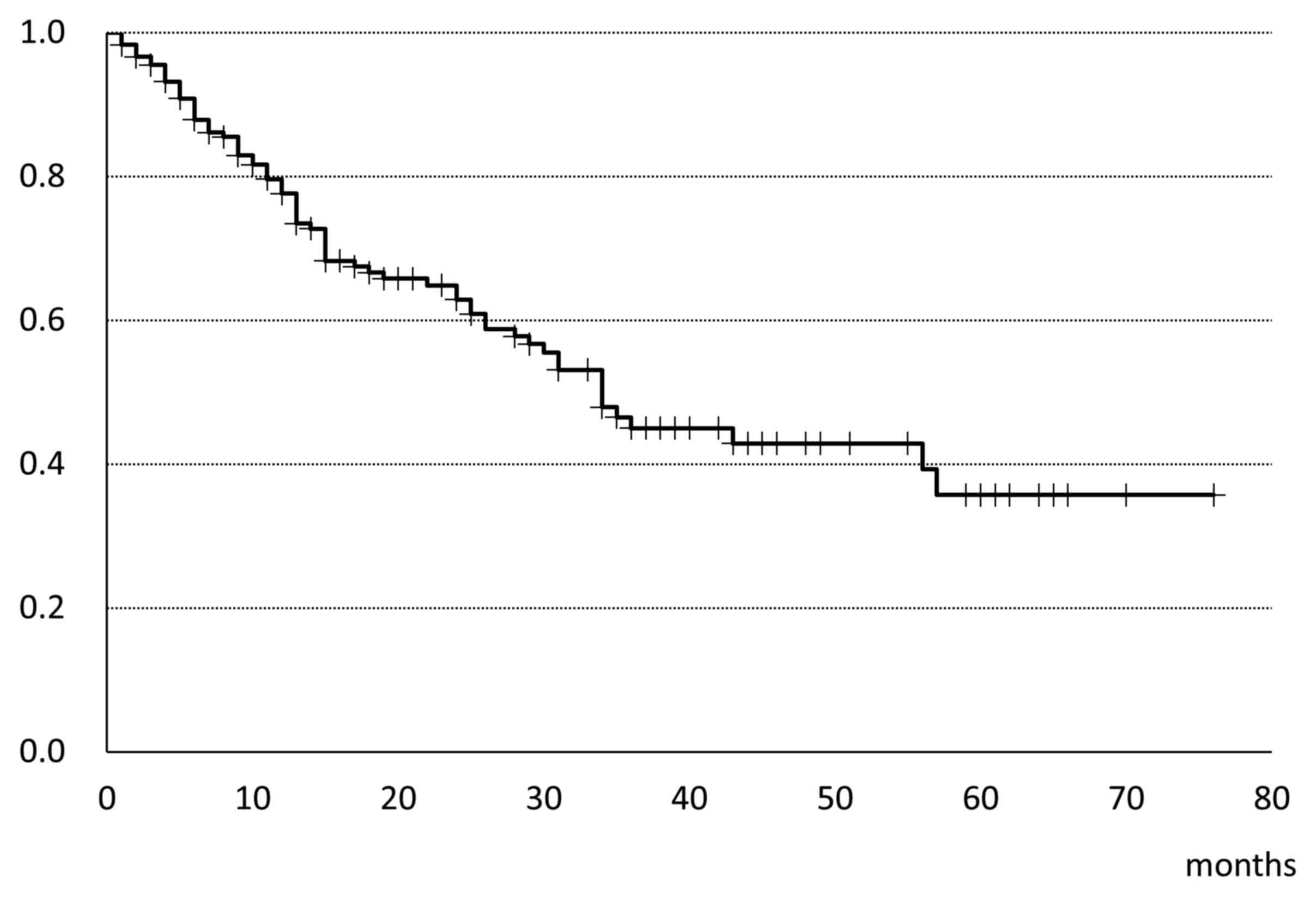

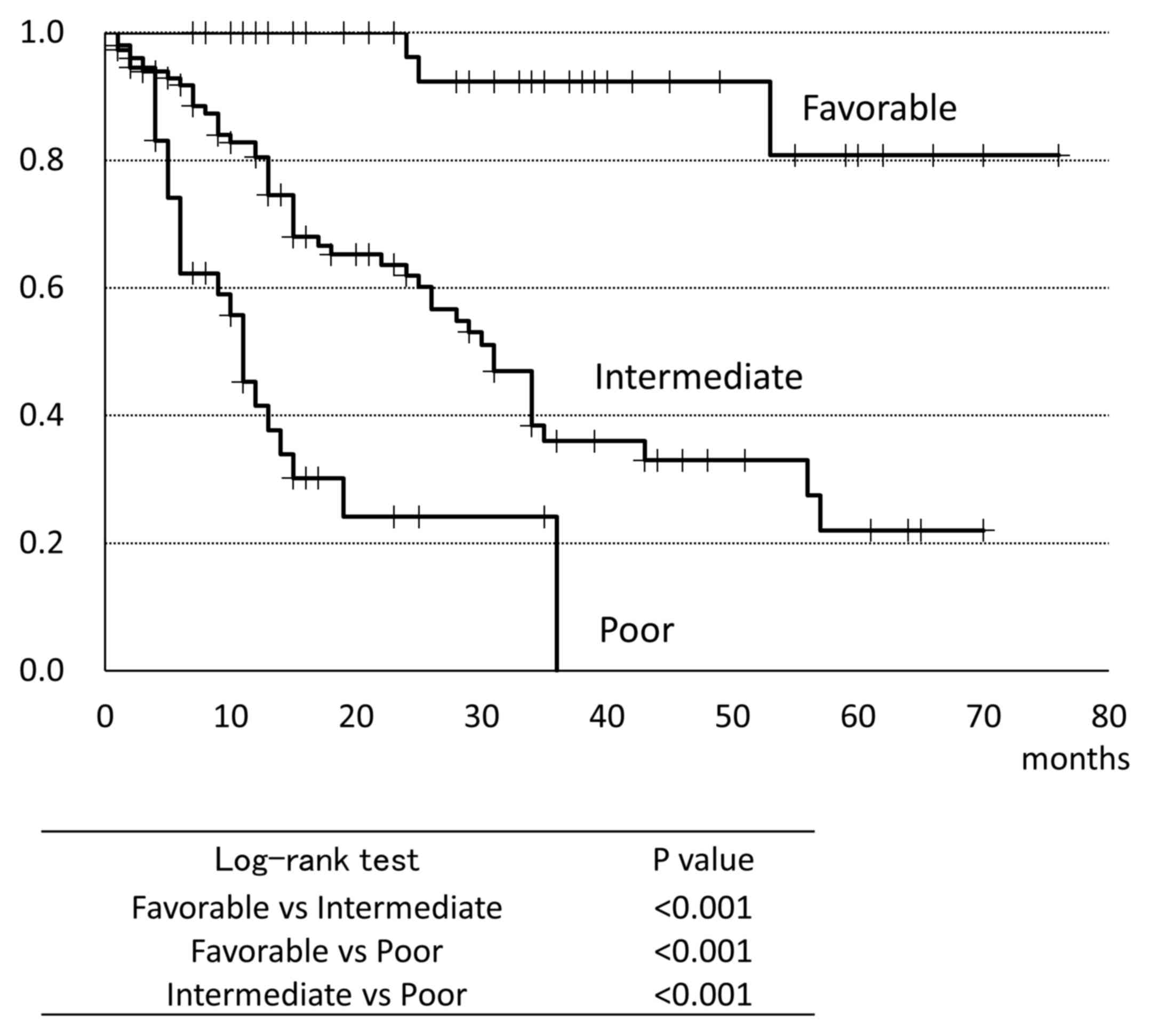

was 34 months (Fig. 1). Fig. 2 shows the OS classified by the MSKCC

criteria. Patients in the favorable group had a significantly

prolonged survival than those in the other groups; conversely, the

patients in the poor group had significantly shorter survival time

compared to those in the other groups (favorable: Not reached;

intermediate 31.0 months; poor: 11.0 months). In univariate

analysis, patients who performed nephrectomy or cytoreductive

nephrectomy had a significantly prolonged survival than those who

did not performed. Concerning the intermediate risk class (126

patients in total), this was subdivided into Intermediate group 1

(64 patients) and intermediate group 2 (62 patients). The median

age of intermediate group 1 was 67 years (range: 40–80); that of

intermediate group 2 was 69 years (range: 39–83). The other patient

characteristics and treatments are detailed in Table II.

| Table I.Patients characteristics and

treatments (N=180). |

Table I.

Patients characteristics and

treatments (N=180).

| Characteristics | Nο. of patients | Percentage |

|---|

| Sex |

|

|

| Male | 140 |

|

|

Female | 40 |

|

| Age, years

(median) | 66 | range, 35–84 |

| MSKCC |

|

|

|

Favorable | 44 | 24.3% |

|

Intermediate | 99 | 55.2% |

| Poor | 37 | 20.5% |

| Nο. of metastatic

organ |

|

|

|

Single | 98 | 54.1% |

|

Multiple | 82 | 45.9% |

| Sites of

metastasis |

|

|

| Lung | 127 | 46.7% |

| Lymph

node | 54 | 20.0% |

| Bone | 51 | 18.8% |

|

Pancreas | 14 | 5.1% |

|

Liver | 13 | 4.8% |

|

Brain | 13 | 4.8% |

| Prior

nephrectomy |

|

|

| Yes | 165 | 91.6% |

| No | 15 | 8.4% |

| Molecular targeted

agents |

|

|

|

1st |

|

|

|

Sunitinib | 108 |

|

|

Sorafenib | 66 |

|

|

Temsilorimus | 6 |

|

|

2nd |

|

|

|

Everolimus | 30 |

|

|

Axitinib | 33 |

|

|

Sunitinib | 20 |

|

|

Temsilorimus | 14 |

|

|

Sorafenib | 2 |

|

|

3rd |

|

|

|

Everolimus | 21 |

|

|

Sunitinib | 7 |

|

|

Axitinib | 7 |

|

|

Sorafenib | 5 |

|

|

Temsirolimus | 5 |

|

|

Pazopanib | 3 |

|

|

4th |

|

|

|

Everolimus | 21 |

|

|

Sunitinib | 7 |

|

|

Axitinib | 7 |

|

|

Sorafenib | 5 |

|

|

Temsirolimus | 5 |

|

|

Pazopanib | 3 |

|

|

5th |

|

|

|

Axitinib | 3 |

|

|

Sorafenib | 2 |

|

| Table II.Results of the Cox proportional

stepwise multivariate analysis for the association between the

clinicopathological variables and cause specific survival. |

Table II.

Results of the Cox proportional

stepwise multivariate analysis for the association between the

clinicopathological variables and cause specific survival.

|

|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Comparison | Overall survival

(months) (median) | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|

| Lung vs. other

organs | 31.0 vs. 34.0 | 1.03

(0.74–1.42) | 0.846 |

|

|

| Lung only vs. other

organs | 36.0 vs. 31.0 | 0.66

(0.40–1.07) | 0.097 |

|

|

| Pancreas vs. other

organs | not reached vs.

31.0 | 0.20

(0.04–0.80) | 0.024 | 0.22

(0.05–0.94) | 0.042 |

| Brain vs. other

organs | 15.0 vs. 34.0 | 1.66

(0.81–3.38) | 0.163 |

|

|

| Lymph node vs.

other organs | 28.0 vs. 34.0 | 1.15

(0.76–1.74) | 0.496 |

|

|

| Liver vs. other

organs | 15.0 vs. 34.0 | 1.88

0.83–4.26) | 0.129 |

|

|

| Bone vs. other

organs | 15.0 vs. 34.0 | 1.23

(0.80–1.89) | 0.334 |

|

|

| Single organ vs.

multiple organs | 44.4 vs. 32.3 |

0.53(0.33–0.84) | 0.007 | 0.51

(0.33–0.82) | 0.005 |

| MSKCC |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Favorable vs. others | not reached vs.

26.0 |

0.07(0.02–0.25) | <0.001 | 0.10

(0.03–0.33) | <0.001 |

| Poor

vs. others | 12.0 vs. 53.0 |

4.21(2.52–7.02) | <0.001 | 2.33

(1.39–3.93) | 0.001 |

| Nephrectomy |

|

|

|

|

|

| Yes vs.

no | 35 vs. 13 |

0.46(0.23–0.93) | 0.030 |

|

|

Patients who had a single metastatic organ lived

significantly longer than those with multiple metastatic organs

(Fig. 3). OS classified according to

metastatic lesions was analyzed using univariate logistic

regression (Table II). Patients

with pancreatic metastasis had a good response to molecular

targeted drugs. Other metastatic lesions did not have a significant

impact on the patients' survival. In multivariate analysis,

pancreatic metastasis, the number of metastatic organs, and MSKCC

criteria were independent risk factors for OS.

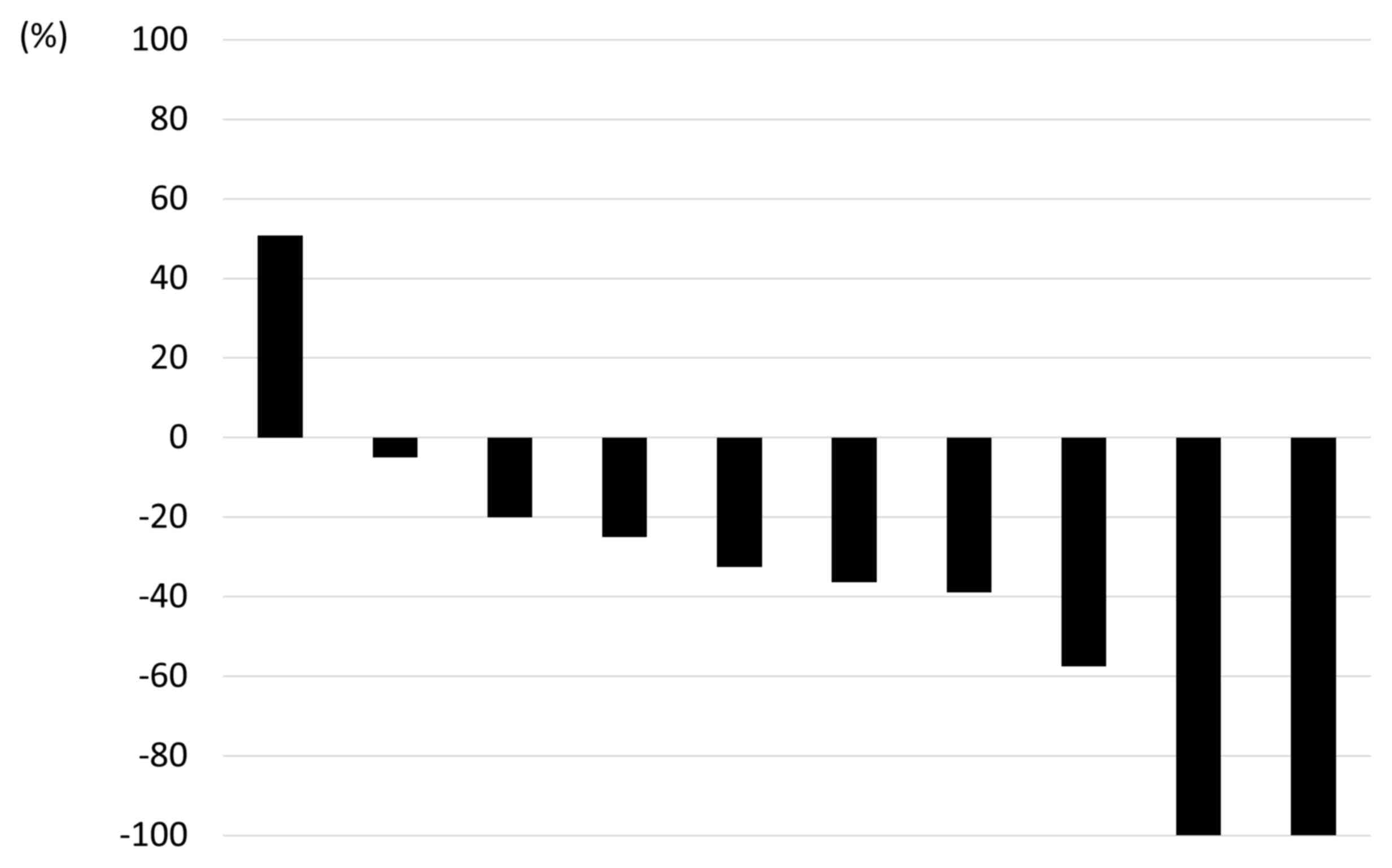

Next, we focused on pancreatic metastasis due to

RCC. The characteristics of patients with pancreatic metastasis and

other metastasis are shown in Table

III. Three out of 14 cases had metastases confined only to the

pancreas; however, all the 3 cases had multiple pancreatic

metastases in pancreatic head and there was no indication for

surgical resection. In patients with pancreatic metastasis, the

time from diagnosis to metastasis was significantly longer than in

cases with other metastasis (unpaired t test, Welch's test). The

maximum reduction from the baseline of the pancreatic tumors in the

10 evaluable patients is shown in Fig.

4. Partial remission was achieved in 6 cases.

| Table III.Characteristics of patients with or

without pancreatic metastasis. |

Table III.

Characteristics of patients with or

without pancreatic metastasis.

|

| Pancreatic

metastasis (N=14) | Other metastasis

(N=166) | P-value |

|---|

| Other metastatic

organs |

|

|

|

|

Lung | 10 | 117 |

|

|

Liver | 1 | 12 |

|

|

Brain | 1 | 11 |

|

| Lymph

node | 4 | 50 |

|

|

Bone | 3 | 48 |

|

|

Others | 6 | 27 |

|

|

None | 3 | – |

|

| Time from diagnosis

to metastasis (months) | 81 (1.5–182.5) | 37.4 (0–232.4) | 0.004 |

Discussion

Treatment of mRCC has changed over the last few

years, and treatment by molecular targeted drugs has become common

(2–4,6,7,20).

Although a number of treatment outcomes have been reported in the

real-world setting (10,23), there are only few reports on the

treatment outcomes classified according to metastatic lesion

(19). We retrospectively

investigated the treatment outcome by metastatic lesion with

molecular targeted drugs, and consequently, identified that

pancreatic metastasis had better response compared to metastasis to

other organs in the molecular targeted therapy era.

In the cytokine therapy era, there was minimal

variation in the metastatic organ in Japanese patients (17). It was reported that lymph node, bone,

hepatic, and brain metastasis correlated with progression on

univariate analysis, but not on multivariate analysis. Shinohara

et al (16) reported that

liver or bone metastasis were independent risk factors. In the

targeted therapy era, McKay et al reported that the presence

of bone and liver metastasis had a negative impact on survival

(19), and another report indicated

that lymph node metastases was associated with poor prognosis in

mRCC patients treated with targeted therapy (24). In Japanese patients, liver metastasis

was an independent factor for OS (10). However, patients with pancreatic

metastasis were very few among the population, and the relationship

between survival and pancreatic metastasis was not studied in these

previous studies. Yuasa et al reported that the pancreatic

metastasis (N=20) occurs a long time (median 7.8 years) after

nephrectomy, and that the OS of these patients is long (median not

reached, 10 year survival rate; 80%) (25), although, among 20 patients, only 6

patients were treated by molecular targeted drugs. Only Grassi

et al (26) and Kalra et

al (27) reported that

pancreatic metastasis is an independent prognostic variable in the

targeted therapy era. We also identified that OS of patients with

pancreatic metastasis was longer than that of those with metastasis

to other organs (not reached vs. 31 months, respectively) in

Japanese patients. According to our findings, the reason that

pancreatic metastasis might carry good prognosis is that pancreatic

metastasis occurred late, showed good response to molecular

targeted drugs, and few patients were classified to have poor

prognosis according to the MSKCC criteria. In fact, our study

showed that time to pancreatic metastasis was longer than that to

other metastases (81 vs. 37.4 months, respectively), and 60% of

patients with pancreatic metastasis achieved partial response.

Moreover, no patients with pancreatic metastasis were classified as

poor risk in our study population. As opposed, Chrom et al

(28) recently reported that the

presence of pancreatic metastasis was not an independent prognostic

factor.

OS for patients with mRCC treated by molecular

targeted drugs was 34 months, this result is comparable to other

reports by Japanese investigators (10,12).

According to the MSKCC criteria (13), survival rates in each group were

clearly stratified. IMDC criteria, which is another risk

classification, is now often adapted to mRCC; however, some of our

study participants had no available neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio,

especially those who were diagnosed before 2010; hence, we did not

investigate the IMDC risk. Although MSKCC criteria was established

in the cytokine therapy era, our results showed that it can be

applied efficiently, even in the era of molecular targeted drugs

(21).

Next, we investigated the relationship between the

number of metastatic organ and OS. OS for patients who had one

metastatic organ was superior to those with multiple organs.

Gerlinger et al mentioned that intratumor heterogeneity can

lead to underestimation of the tumor genomics landscape portrayed

from single tumor-biopsy samples, and may present major challenges

to personalized-medicine and biomarker development (29). Therefore, it can be said that it is a

reasonable result that the prognosis is better if the metastatic

lesion is in a single organ. As might be expected, a single

metastasis in a single organ must be enucleated because complete

resection of RCC metastases may be associated with log-term

survival (30,31), and we also performed metastatectomy

in such cases. In this study, the patient recruited was inoperable

due to the presence of multiple metastases in a single organ.

Despite that the cases who underwent metastasis resection were not

included, the prognosis was better in the single organ metastasis

group than in the multiple organ group; it is said that early

detection and prompt treatment of metastasis are useful.

This study was a retrospective study and thus has

certain limitations. Treatment strategy for mRCC patients is

changing across time, so there is minimum variation due to the

class of molecular targeted drugs. Treatment with immune checkpoint

inhibitors has also increased, and future investigation is

necessary.

In conclusion, the presence of pancreatic metastasis

in patients with mRCC treated with molecular targeted therapy has a

positive impact on survival. The site of metastasis may possibly be

used for risk-stratification of patients with mRCC.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analysed during the

current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

YS and ST conceived and designed the study and were

major contributors in writing the manuscript. TI, MK, NN, TN and TY

designed the study and revised the manuscript. SY analyzed and

interpreted the data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Permission to access the database for review of the

medical records of these patients was approved by the Local

Research Ethics Committee at Osaka City University (approval nο.

3441).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr Satoshi Tamada received remuneration for a

lecture from Pfizer Japan (Tokyo, Japan), Bayer Japan (Tokyo,

Japan) and Novartis Pharma Japan (Tokyo, Japan). The other authors

have declared that they have no competing interests.

References

|

1

|

Shinohara N and Abe T: Prognostic factors

and risk classifications for patients with metastatic renal cell

carcinoma. Int J Urol. 22:888–897. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, Szczylik

C, Oudard S, Siebels M, Negrier S, Chevreau C, Solska E, Desai AA,

et al: Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N

Engl J Med. 356:125–134. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P,

Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik

C, Kim ST, et al: Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic

renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 356:115–124. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Oudard S, Hutson

TE, Porta C, Bracarda S, Grünwald V, Thompson JA, Figlin RA,

Hollaender N, et al: Efficacy of everolimus in advanced renal cell

carcinoma: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III

trial. Lancet. 372:449–456. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Rini BI, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Kaprin A,

Szczylik C, Hutson TE, Michaelson MD, Gorbunova VA, Gore ME,

Rusakov IG, et al: Comparative effectiveness of axitinib versus

sorafenib in advanced renal cell carcinoma (AXIS): A randomised

phase 3 trial. Lancet. 378:1931–1939. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J,

Hawkins R, Guo J, Nathan P, Staehler M, de Souza P, Merchan JR, et

al: Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma.

N Engl J Med. 369:722–731. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J,

Figlin R, Kapoor A, Staroslawska E, Sosman J, McDermott D, Bodrogi

I, et al: Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced

renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 356:2271–2281. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Ninomiya N, Tamada S, Kato M, Yamasaki T,

Iguchi T and Nakatani T: Prolonging survival in metastatic renal

cell carcinoma patients treated with targeted anticancer agents: A

single-center experience of treatment strategy modifications. Can J

Urol. 22:7798–7804. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Kondo T, Takagi T, Kobayashi H, Iizuka J,

Nozaki T, Hashimoto Y, Ikezawa E, Yoshida K, Omae K and Tanabe K:

Superior tolerability of altered dosing schedule of sunitinib with

2-weeks-on and 1-week-off in patients with metastatic renal cell

carcinoma-comparison to standard dosing schedule of 4-weeks-on and

2-weeks-off. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 44:270–277. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Miyake H, Miyazaki A, Harada K and

Fujisawa M: Assessment of efficacy, safety and quality of life of

110 patients treated with sunitinib as first-line therapy for

metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Experience in real-world clinical

practice in Japan. Med Oncol. 31:9782014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Akaza H, Oya M, Iijima M, Hyodo I, Gemma

A, Itoh H, Adachi M, Okayama Y, Sunaya T and Inuyama L: A

large-scale prospective registration study of the safety and

efficacy of sorafenib tosylate in unresectable or metastatic renal

cell carcinoma in Japan: Results of over 3200 consecutive cases in

post-marketing all-patient surveillance. Jpn J Clin Oncol.

45:953–962. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Shinohara N, Obara W, Tatsugami K and

Naito S, Kamba T, Takahashi M, Murai S, Abe T, Oba K and Naito S:

Prognosis of Japanese patients with previously untreated metastatic

renal cell carcinoma in the era of molecular-targeted therapy.

Cancer Sci. 106:618–626. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Murphy BA, Russo P and

Mazumdar M: Interferon-alfa as a comparative treatment for clinical

trials of new therapies against advanced renal cell carcinoma. J

Clin Oncol. 20:289–296. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Ko JJ, Xie W, Kroeger N, Lee JL, Rini BI,

Knox JJ, Bjarnason GA, Srinivas S, Pal SK, Yuasa T, et al: The

International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium

model as a prognostic tool in patients with metastatic renal cell

carcinoma previously treated with first-line targeted therapy: A

population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 16:293–300. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P,

Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Pili

R, Bjarnason GA, et al: Overall survival and updated results for

sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic

renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 27:3584–3590. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Shinohara N, Nonomura K, Abe T, Maruyama

S, Kamai T, Takahashi M, Tatsugami K, Yokoi S, Deguchi T, Kanayama

H, et al: A new prognostic classification for overall survival in

Asian patients with previously untreated metastatic renal cell

carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 103:1695–1700. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Naito S, Yamamoto N, Takayama T, Muramoto

M, Shinohara N, Nishiyama K, Takahashi A, Maruyama R, Saika T,

Hoshi S, et al: Prognosis of Japanese metastatic renal cell

carcinoma patients in the cytokine era: A cooperative group report

of 1463 patients. Eur Urol. 57:317–325. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Patil S, Figlin RA, Hutson TE, Michaelson

MD, Négrier S, Kim ST, Huang X and Motzer RJ: Prognostic factors

for progression-free and overall survival with sunitinib targeted

therapy and with cytokine as first-line therapy in patients with

metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 22:295–300. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

McKay RR, Kroeger N, Xie W, Lee JL, Knox

JJ, Bjarnason GA, MacKenzie MJ, Wood L, Srinivas S, Vaishampayan

UN, et al: Impact of bone and liver metastases on patients with

renal cell carcinoma treated with targeted therapy. Eur Urol.

65:577–584. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Motzer RJ, Escudier B, Tomczak P, Hutson

TE, Michaelson MD, Negrier S, Oudard S, Gore ME, Tarazi J,

Hariharan S, et al: Axitinib versus sorafenib as second-line

treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma: Overall survival

analysis and updated results from a randomised phase 3 trial.

Lancet Oncol. 14:552–562. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Motzer RJ, Bukowski RM, Figlin RA, Hutson

TE, Michaelson MD, Kim ST, Baum CM and Kattan MW: Prognostic

nomogram for sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell

carcinoma. Cancer. 113:1552–1558. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wahlgren T, Harmenberg U, Sandstrom P,

Sandström P, Lundstam S, Kowalski J, Jakobsson M, Sandin R and

Ljungberg B: Treatment and overall survival in renal cell

carcinoma: A Swedish population-based study (2000–2008). Br J

Cancer. 108:1541–1549. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kroeger N, Pantuck AJ, Wells JC, Lawrence

N, Broom R, Kim JJ, Srinivas S, Yim J, Bjarnason GA, Templeton A,

et al: Characterizing the impact of lymph node metastases on the

survival outcome for metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients

treated with targeted therapies. Eur Urol. 68:506–515. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Yuasa T, Inoshita N, Saiura A, Yamamoto S,

Urakami S, Masuda H, Fujii Y, Fukui I, Ishikawa Y and Yonese J:

Clinical outcome of patients with pancreatic metastases from renal

cell cancer. BMC Cancer. 15:462015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Grassi P, Verzoni E, Mariani L, De Braud

F, Coppa J, Mazzaferro V and Procopio G: Prognostic role of

pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: Results from an

Italian center. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 11:484–488. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kalra S, Atkinson BJ, Matrana MR, Matin

SF, Wood CG, Karam JA, Tamboli P, Sircar K, Rao P, Corn PG, et al:

Prognosis of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and

pancreatic metastases. BJU Int. 117:761–765. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Chrom P, Stec R, Bodnar L and Szczylik C:

Prognostic significance of pancreatic metastases from renal cell

carcinoma in patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors.

Anticancer Res. 38:359–365. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Gerlinger M, Rowan AJ, Horswell S, Math M,

Larkin J, Endesfelder D, Gronroos E, Martinez P, Matthews N,

Stewart A, et al: Intratumor heterogeneity and branched evolution

revealed by multiregion sequencing. N Engl J Med. 366:883–892.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Alt AL, Boorjian SA, Lohse CM, Costello

BA, Leibovich BC and Blute ML: Survival after complete surgical

resection of multiple metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Cancer.

117:2873–2882. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Naito S, Kinoshita H, Kondo T, Shinohara

N, Kasahara T, Saito K, Takayama T, Masumori N, Takahashi W,

Takahashi M, et al: Prognostic factors of patients with metastatic

renal cell carcinoma with removed metastases: A multicenter study

of 556 patients. Urology. 82:846–851. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|