Introduction

Pulmonary sclerosing hemangioma (PSH) is an uncommon

benign tumor of the lungs, first reported by Liebow and Hubbell in

1956(1). Its origin has been

suggested to be vascular, mesothelial, mesenchymal, epithelial and

neuroendocrine (1-5),

but immunohistochemical examination suggests that PSH is derived

from primitive respiratory epithelium. It primarily affects Asian

women and the female: Male ratio is 5:1 (6,7). PSH

predominantly presents as a solitary, sharply defined slow-growing

mass, although it may present as multiple lesions (8). On imaging, PSH appears as a mass with

distinct margins, and the majority of the patients are

asymptomatic. Definitive diagnosis requires resection and

postoperative histopathological examination. Due to its atypical

image presentations, PSH may be easily misdiagnosed as a malignant

tumor prior to surgery, with a misdiagnosis rate that ranges from

25 to 56% (8). We herein report a

case of PSH and perform a review of the literature to explore the

clinical management of PSH.

Case report

A 23-year-old unmarried woman was hospitalized after

a mass was incidentally found in her right lung during routine

physical examination. The patient had a history of allergic

reaction to penicillin and cephalosporin. The patient was in good

general health and had no unhealthy habits, such as drug or alcohol

abuse or smoking. The patient's personal, menstrual and family

history were unremarkable.

The chest computed tomography (CT) of the patient

revealed several shadows in the right lung during a physical

examination in October 2014. The patient visited Qingdao Chest

Hospital (Qingdao, China) for further evaluation and the

γ-interferon release testing was found to be positive. The patient

was diagnosed with tuberculosis and was started on antituberculosis

treatment with rifampicin, armazide, ethambutol and pyrazinamide.

The patient started to experience intermittent fevers over the next

2 months of antituberculosis treatment, with the highest

temperature reaching 39˚C, usually improving at night and relieved

by ibuprofen. Interestingly, the patient had no history of cough,

expectoration, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations or weight loss.

The patient underwent regular chest CT re-examinations during the

antituberculosis treatment, which revealed no changes in the

lesions. The patient accepted CT examination again in March 2015

and no obvious changes were evident in the images of the right

lung. Percutaneous lung biopsy was performed, and histopathological

examination revealed inflammatory and hyperplastic changes. Most

importantly, the antituberculosis treatment was continued based on

the results of postoperative pathology.

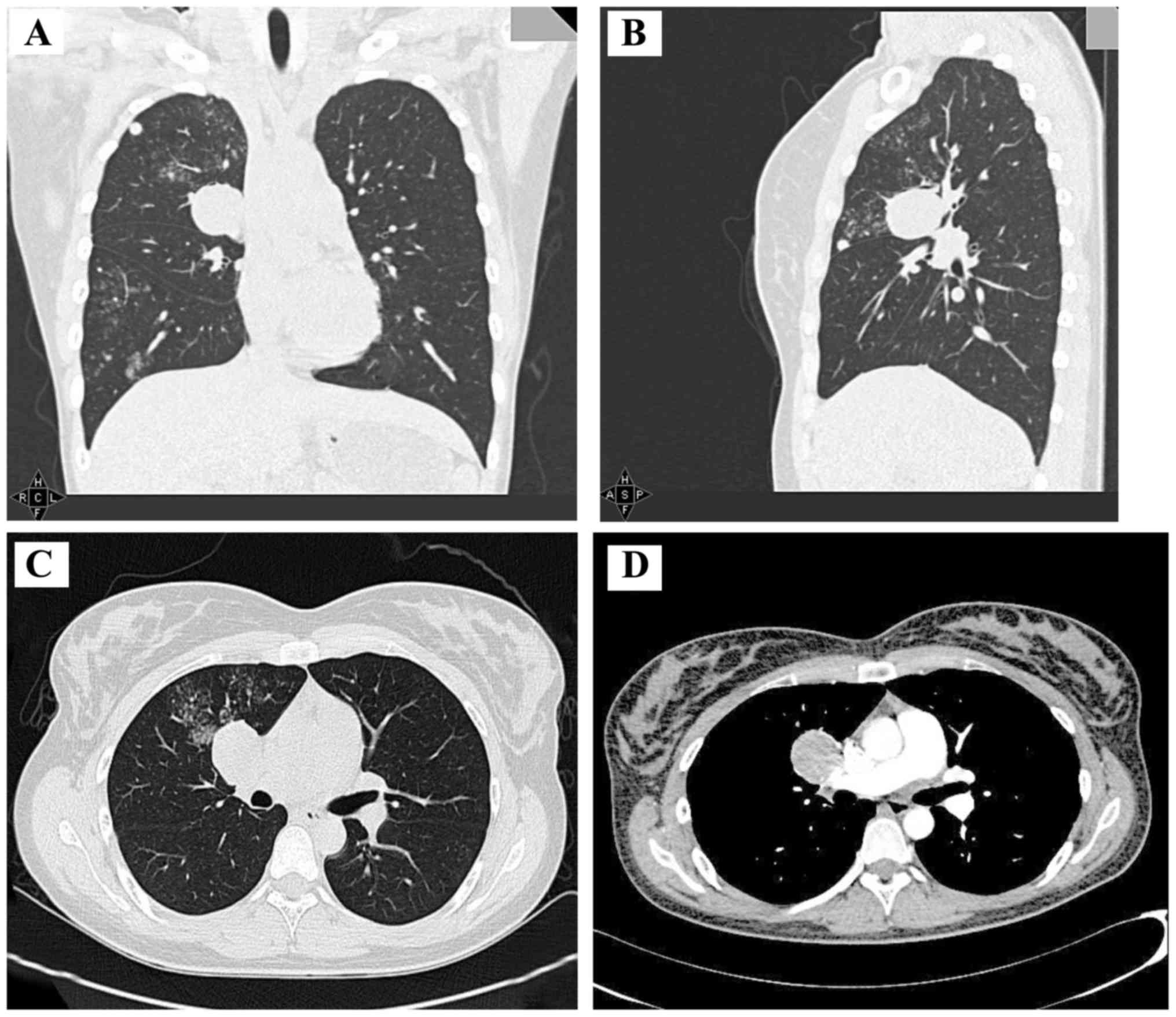

The patient first visited Chengdu Military General

Hospital (Chengdu, China) at the end of September 2015, and a CT

scan revealed a circular mass of soft tissue density in the right

upper pulmonary hilum. In addition, the right lung exhibited

scattered dot films and small nodules, consistent with the imaging

findings of pulmonary tuberculosis. Admission was recommended for

further evaluation, but the patient declined due to work

responsibilities. Antituberculosis treatment was continued on an

outpatient basis and further chest CT scans were performed in June

2016, April 2017 and August 2017. The CT scan performed in August

2017 revealed an increased number of dot films and small nodules in

the right lung, with the additional appearance of flakes of blurry

shadows (Figs. 1 and 2). The patient was then admitted to the

hospital and further examinations were undertaken.

The physical examination of the patient was normal.

The findings on routine blood and urine tests and bronchoscopy were

normal, apart from the results of the γ-interferon release testing.

In order to reach a definitive diagnosis, positron emission

tomography (PET)-CT was performed (Fig.

3), revealing the presence of multiple nodules of varying sizes

and densities. Furthermore, increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake was

observed in some of the nodules with calcification. As tuberculosis

recurrence was first suspected, the patient underwent thoracoscopic

surgery with right lung nodulectomy. Based on the postoperative

pathological examination of the nodules, the lesions were diagnosed

as multiple PSH, and four different histological patterns were

identified: Papillary, solid, sclerotic and hemorrhagic (Fig. 4A). Immunohistochemical evaluation of

the lesions revealed positive staining for thyroid transcription

factor (TTF)1 (Fig. 4B) and

cytokeratin (CK) 8/18 (Fig. 4C), but

negative staining for smooth muscle actin (Fig. 4E). The Ki-67 labeling index was 1%.

(Fig. 4D).

All examinations and medical procedures were

approved by the patient and her family.

Discussion

PSH is a benign tumor of the lungs with variable

histological characteristics. PSH was originally considered to be

of vascular origin due to the obvious characteristics of

hemangioma. After the first description in 1956 by Liebow and

Hubbel (1), several theories

regarding its origin were introduced, including vascular (1), mesothelial (2), mesenchymal (3), epithelial (4) and neuroendocrine (5). Currently, the results of the

immunohistochemical examination suggest that PSH is derived from

primitive respiratory epithelium. PSH has been reported to be more

prevalent in East Asian rather than in Western countries, and

typically affects middle-aged adults and exhibits a female

predominance, with women comprising ~80% of PSH patients (6,7). In the

majority of the cases (~95%), PSH presents as a solitary

slow-growing mass located in the peripheral lung parenchyma, except

for 4% of the cases that present as multiple lesions (8). The tumor size may vary from 0.3 to 8 cm

in greatest diameter, but the majority measure <3 cm. PSH is

almost always benign, with only 4% of PSHs invading the visceral

pleura and only 1% growing into the mediastinum or the bronchial

cavity. The right lung, particularly the lower lobe, has been

reported to be most commonly affected by PSH. The findings on CT

scans include a mass with distinct margins and increased density on

contrast-enhanced CT. The majority (80%) of PSHs are asymptomatic

or present with cough, hemoptysis and, occasionally, chest

pain.

Histologically, PSH includes two essential types of

tumor cells: Round stromal cells and surface cuboidal cells. Round

stromal cells with absent or rare clear nucleoli are small and

well-circumscribed. However, the surface cuboidal cells lining

papillary structures exhibit characteristics of bronchiolar

epithelium and type II pneumocytes. These cells may display

different degrees of nuclear heterogeneity. Therefore, they may be

arranged into four different histological patterns: Papillary,

solid, sclerotic and hemorrhagic. In the present case, although the

immunohistochemical examination revealed that the two cell types

were positive for TTF-1 and epithelial membrane antigen, the

expression of pancytokeratin A and various CKs were different in

the two cell types, as pancytokeratin A and CK staining was only

observed in the surface cells of the mass. Molecular studies

confirmed that both cell types were clonal in nature, demonstrating

that PSH is a true neoplasm.

The origin and progression of PSH remain

controversial. The current consensus is that primary papillary

alveolar epithelial cells proliferate and cover the fibrous tissue

of the alveolar wall. At this stage, the epithelial cells may be

atypical, but not malignant. Subsequently, sclerosis of

interstitial alveolar cells is aggravated, leading to implantation

of capillaries. As a consequence, hemorrhage occurs in the residual

alveolar cavity, causing a hemosiderin reaction or accumulation of

vacuolar macrophages and alveolar destruction.

Our patient had no obvious causes or positive

symptoms in the early stages of the disease. Several shadows were

located in the right pulmonary hilum, and the right lower lung was

surrounded by inflammatory exudations that were consistent with the

critical changes of pulmonary tuberculosis. Antituberculosis

therapy was recommended by the first attending physician, as well

as by other consultants thereafter, based on the consideration that

China is a region of high incidence of tuberculosis. The patient

was positive for whole-blood γ-interferon release assay. After

ruling out malignant tumors, common bacteria in the region, and

infection by atypical pathogens, tuberculosis remained the most

likely diagnosis. The patient also developed high fevers in the

afternoon, which was consistent with the typical symptoms of

tuberculosis. More importantly, the high fever disappeared after

antituberculosis treatment, suggesting treatment efficacy. However,

the pulmonary lesions increased after 6 months of treatment and the

biopsy results indicated inflammatory changes in the lungs.

Antituberculosis therapy was continued, as the patient reported no

feeling of discomfort and the duration of antituberculosis therapy

was deemed insufficient. Unfortunately, the CT scan performed in

August 2017 revealed that the pulmonary lesions had increased after

the patient completed a 1-year course of antituberculosis

treatment. In addition, the PET-CT results indicated recrudescence

of tuberculosis. The clinical manifestations of the patient were

carefully analyzed and it was concluded that the diagnosis of

tuberculosis could not fully explain the patient's condition and

all the imaging findings. Thoracoscopic surgery and right lung

nodulectomy were performed in order to pathologically diagnose the

patient. Surgical excision is considered the best choice for single

PSH, while long-term follow-up is required to determine the

prognosis of multiple PSHs.

In conclusion, we herein present a rare case of PSH

with symptoms of discontinuous fever and multiple pulmonary nodules

that was misdiagnosed as tuberculosis in its initial stages.

Following adequate antituberculosis therapy, the lesions progressed

but the patient remained asymptomatic. Although bronchoscopy and

lung biopsy through percutaneous paracentesis were performed, there

were no positive results. Finally, thoracoscopy and

immunohistochemical examination were used to reach a definitive

diagnosis. In the literature, surgical resection is the preferred

treatment for solitary PSH; however, for multiple PSHs, continuous

follow-up and observation are crucial, as there is yet no effective

treatment. Although rare, PSH should be considered when the

suspected diagnosis contradicts the symptoms and results of

auxiliary examinations. Therefore, physicians must remain highly

vigilant in such cases to reach an accurate diagnosis and deliver

effective treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank colleagues from the

Imaging, Pathology, Laboratory and Thoracic Surgery Departments of

General Hospital of Western Theater Command for help in diagnosing

the patient.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Authors' contributions

HL was the patient's doctor. LM analyzed the data

and wrote the article together with HL and TZ. YC was pathologist

and confirmed the pathological diagnosis. DP, ZL and XD helped

during the treatment and collected data. ZX and ZC directed the

treatment of the patient, collection of data and writing of the

article.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All examinations and medical procedures were

approved by the patient and her family.

Patient consent for publication

The patient agreed for the case study to be

published.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Liebow AA and Hubbell DS: Sclerosing

hemangioma (histiocytoma, xanthoma) of the lung. Cancer. 9:53–75.

1956.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Ng WL and Ma L: Is sclerosing hemangioma

of lung an alveolar mixed tumour? Pathology. 15:205–211.

1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Huszar M, Suster S, Herczeg E and Geiger

B: Sclerosing hemangioma of the lung. Immunohistochemical

demonstration of mesenchymal origin using antibodies to

tissue-specific intermediate filaments. Cancer. 58:2422–2427.

1986.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Satoh Y, Tsuchiya E, Weng SY, Kitagawa T,

Matsubara T, Nakagawa K, Kinoshita I and Sugano H: Pulmonary

sclerosing hemangioma of the lung. A type II pneumocytoma by

immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopic studies. Cancer.

64:1310–1317. 1989.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Xu HM, Li WH, Hou N, Zhang SG, Li HF, Wang

SQ, Yu ZY, Li ZJ, Zeng MY and Zhu GM: Neuroendocrine

differentiation in 32 cases of so-called sclerosing hemangioma of

the lung: Identified by immunohistochemical and ultrastructural

study. Am J Surg Pathol. 21:1013–1022. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Katzenstein AL, Weise DL, Fulling K and

Battifora H: So-called sclerosing hemangioma of the lung. Evidence

for mesothelial origin. Am J Surg Pathol. 7:3–14. 1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Devouassoux-Shisheboran M, Hayashi T,

Linnoila RI, Koss MN and Travis WD: A clinicopathologic study of

100 cases of pulmonary sclerosing hemangioma with

immunohistochemical studies: TTF-1 is expressed in both round and

surface cells, suggesting an origin from primitive respiratory

epithelium. Am J Surg Pathol. 24:906–916. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lee ST, Lee YC, Hsu CY and Lin CC:

Bilateral multiple sclerosing hemangiomas of the lung. Chest.

101:572–573. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|