Introduction

Endometriosis is a pathology of the female

reproductive tract (1), with a

morbidity rate of ~10% in women of reproductive age (2). Ovarian endometriomas (OE) are clinical

manifestations of endometriosis and comprise a risk factor for the

development of ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma (CCC) and

endometrioid carcinoma, regarded as endometriosis-associated

ovarian cancers (EAOC) (3,4). The primary histological type of EAOC

in Asia is CCC, accounting for 20% of all ovarian cancers (5). The prevalence of EAOC will likely

increase along with that of endometriosis; however, the underlying

mechanisms associated with carcinogenesis are controversial. Hence,

it is important to elucidate the mechanisms underlying malignant

transformation and pathogenesis of EAOC.

Endometriosis is caused due to the reflux of

menstrual blood containing endometrial tissues (6), and OE form when menstrual blood flows

into the ovary (6), carrying

endometrial epithelium and endometrial stroma into the ovary

(7). Moreover, iron within the

menstrual blood serves as an etiological factor for the development

of ovarian cancer from OE (8-10).

However, the precise mechanism through which iron ions flow in

endometrial epithelial cells remains unknown.

Iron ions are primarily absorbed by the epithelium

of the intestinal tract (11),

after which iron is transported by divalent metal transporter1

(DMT1) that imports and ferroportin (FPN) that exports iron ions

(12,13). Furthermore, transferrin receptors

(TfR) uptake iron ions in other organs (14). These transporters regulate

intracellular iron concentrations (11). Meanwhile, iron transporters in OE

and CCC have rarely been investigated, and the mechanism of iron

flow through endometrial epithelial cells of OE or CCC tumor cells

remains unclear.

Macrophages within the endometrial stroma of OE

accumulate around the epithelium to englobe iron (7). The M1 macrophage phenotype induces

inflammatory cytokines and bactericidal activity (15), and M2 macrophages polarize toward

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) after T cells and tumor cells

release cytokines such as IL-4, IL-13, and macrophage

colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) (15). Thereafter, TAMs migrate to hypoxic

regions, where they release growth factors and angiogenetic factors

that promote proliferation and metastasis (16). Although M2 macrophages have been

detected in OE and CCC (17,18),

their effect on OE carcinogenesis has not been investigated.

The present study aimed to immunohistochemically

determine the expression of iron transporters in the endometrial

epithelium of OE and tumor cells of CCC. We also evaluated the

relation of macrophages to endometrial epithelial carcinogenesis in

OE.

Materials and methods

Samples

The study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of Tokyo Women's Medical University Hospital (Approval number

5371). We retrospectively analyzed 20 OE tissues without malignant

lesions and 18 ovarian CCC that were surgically excised at Tokyo

Women's Medical University Hospital between January 2014 and

December 2019. Opt-out informed consent was obtained from all

patients.

Perls Prussian blue staining

Tissues were stained with Perls Prussian blue using

potassium hexacyanoferrate (II) trihydrate (Wako Pure Chemical

Industries, Osaka, Japan) and enhanced with Nuclear Fast Red (Cosmo

Bio Co, Tokyo, Japan).

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)

staining and immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections (4 µm) were

deparaffinized for 10 min. Then the sections were stained with

H&E according to routine hospital procedures. For

immunohistochemistry, antigen was retrieved by autoclaving for 20

min or microwave heating for 15 min in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer,

pH 6.0 or 9.0. Nonspecific protein binding in tissue sections was

blocked using Protein Block Serum-Free (Dako A/S, Glostrup,

Denmark) at 25˚C, for 20 min. The sections were incubated overnight

at 4˚C with primary antibodies, followed by secondary antibodies

(Dako) for 30 min at 25˚C, and finally with 3,3'-diaminobenzidine

(Nichirei Biosciences, Tokyo, Japan) to visualize antigen binding.

Nuclei were stained with hematoxylin (Wako Pure Chemical

Industries). Primary antibodies against the following were used:

DMT1 (1:800), TfR (1:500), CD68 (1:400), CD11c (1:500), CD163

(1:500), and CD206 (1:5,000) (all from Abcam, Cambridge, United

Kingdom), FPN (1:400; Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO, USA), Ki67

(1:100) and cytokeratin (1:200) (both from Dako), and CD10 (1: 50;

Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Samples prepared in the same

manner but without incubation with the primary antibodies were used

as negative controls (data not shown).

Immunohistochemistry analysis

The intensity of DMT1, TfR, and FPN staining was

scored using an arbitrary scale as 0, absent; 1, light; 2,

moderate; 3, intense. We used the score that was the most prevalent

in 10 fields. Due to endometrial epithelial detachment, 10 fields

could not be evaluated in three OE samples, and hence, these

samples were excluded from the analysis.

We evaluated CD11c, CD163, and CD206 expression as

the average number of antibody-positive cells counted in 10 fields

at x400 magnification. We evaluated ratios (%) of Ki67-positive

nuclei and averaged the numbers of cells counted at x400

magnification in 10 fields. Two pathologists assessed the

immunohistochemical scores and numbers of positive cells in all

sections.

Statistical analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using

JMP® 14 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Continuous

variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical

variables (Nulliparous and Premenopause) are presented as numbers

(percentage) and compared with χ2 test or Fisher's exact

test. Shapiro-Wilk test was performed to determine if the

continuous variables were normally distributed. The levels of CA125

are expressed as the median with interquartile range (IQR) as they

were not normally distributed. Comparison of two groups with

normally distributed data (mean age and maximal cyst/tumor

diameter) was performed using Welch's t-test; otherwise, comparison

of continuous variables (median CA125) was performed using the

non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum test. Two groups and more than two

groups were compared using the non-parametric Wilcoxon rank sum

test and Steel-Dwass test (used after Kruskal-Wallis test),

respectively, to confirm the significance of iron transport

proteins and the number of positively immunostained cells.

Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Clinical features

Table I lists the

clinical features of the 18 CCC patients and 20 OE patients. The

average age of the CCC (56 years) and OE groups (47 years) differed

significantly (P=0.0105). Most CCC patients had a stage I disease,

according to the International Federation of Gynecology and

Obstetrics (FIGO) staging guidelines. Of the 18 CCC patients, seven

had a medical history of OE, two had a histopathological diagnosis

of OE, one had both medical history and histopathological diagnosis

of OE, and the medical history of OE in eight patients was unknown.

The maximal tumor diameter was significantly larger in CCC than

that in OE (P<0.001).

| Table ICharacteristics of patients with CCC

(n=18) or OE (n=20). |

Table I

Characteristics of patients with CCC

(n=18) or OE (n=20).

| Variable | CCC | OE | P-value |

|---|

| Mean age (SD),

years | 56(11) | 47(3) | 0.0105 |

| Nulliparous, n

(%) | 9(50) | 13(65) | 0.5118 |

| Premenopause, n

(%) | 5(27) | 19(95) | <0.001 |

| Maximal cyst/tumor

diameter, mean (SD), mm | 123(39) | 46(21) | <0.001 |

| Median CA125 (IQR),

U/ml | 45 (21-184) | 58 (28-172) | 0.6742 |

| FIGO stage, n

(%) | | | |

|

I | 14(77) | | |

|

II | 1(5) | | |

|

III | 3(16) | | |

|

IV | 0 (0) | | |

| OE positive, n

(%) | 10(55) | | |

| Iron deposition

positive, n (%) | 13(72) (in cancer

cells and stroma) | 4(20) (in

endometrial epithelium) and 20(100) (throughout stroma) | |

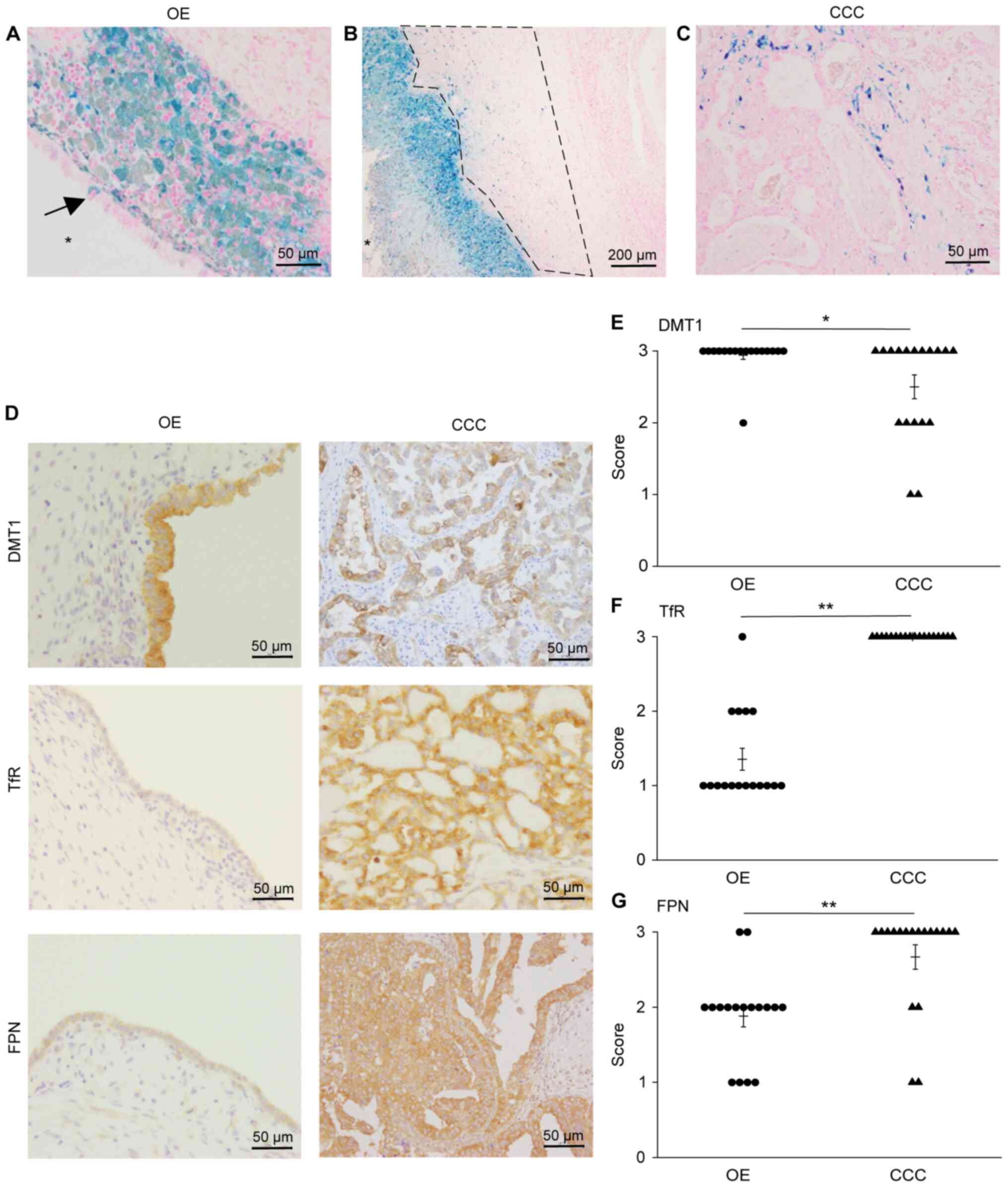

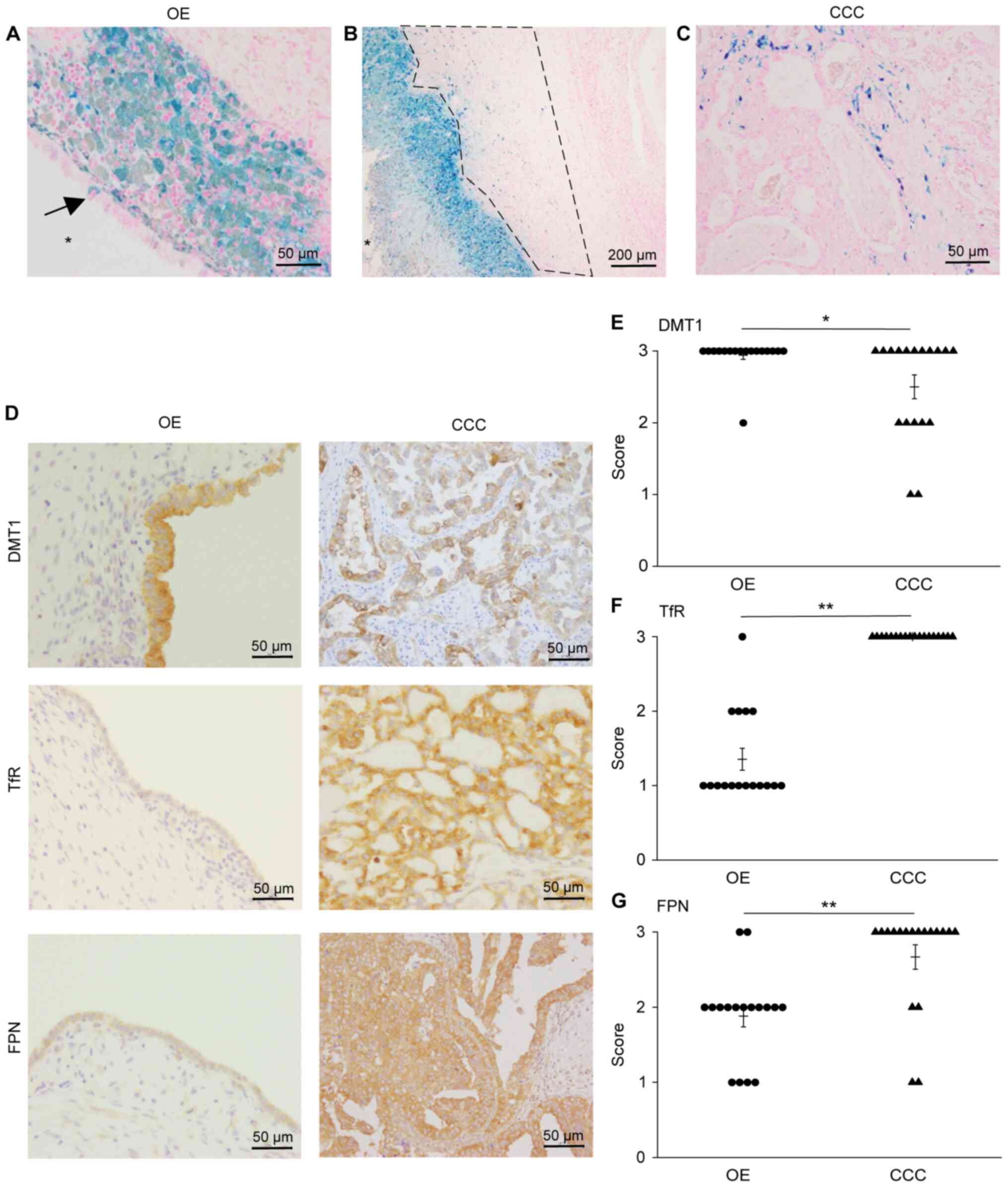

Iron deposition in OE and CCC

We initially investigated iron localization in OE

and CCC by staining tissue sections with Prussian blue (Fig. 1). Iron was deposited in the

endometrial epithelium (Fig. 1A

arrow) of four OE samples and englobed macrophages in the stroma

just below the epithelium (Fig. 1A)

of all OE samples. Iron was deposited throughout the stroma in all

OE specimens (Table I). Stroma

located beneath the aggregated englobed macrophages (referred to

herein as ‘deep layer’; Fig. 1B,

region within the dotted line) also contained iron. Iron was

deposited in CCC cancer cells and stroma in 13 specimens (Fig. 1C and Table I).

| Figure 1Iron deposits detected by Prussian

blue staining and expression of iron transport proteins in the

endometrial epithelium of OE and ovarian CCC tumor cells. (A) Iron

deposits in the endometrial epithelium of OE (arrow). Macrophages

englobed with iron are seen immediately below the epithelium.

Magnification, x400. Scale bar, 50 µm. The star (*) indicates the

lumen of OE. (B) Deep layer represents stroma beneath aggregated

englobed macrophages (region within the dotted line). Iron deposits

observed in englobed macrophages and deep layer. Magnification,

x100. Scale bar, 200 µm. The star (*) indicates the lumen of OE.

(C) Iron deposits in tumor cells and stroma of CCC. Magnification,

x400. Scale bar, 50 µm. (D) Immunolocalization of DMT1, TfR and

FPN. Magnification, x400. Scale bar, 50 µm. Comparison of (E) DMT1,

(F) TfR and (G) FPN expression. *P<0.05 and

**P<0.001 via Wilcoxon rank sum test. CCC, clear cell

adenocarcinoma; OE, ovarian endometrioma; DMT1, divalent metal

transporter 1; TfR, transferrin receptor; FPN, ferroportin. |

Immunostaining for iron transport

proteins

Considering that iron deposition was observed in

both OE and CCC, we investigated the expression of iron transport

proteins DMT1, TfR, and FPN by immunostaining (Fig. 1D). All specimens of OE epithelium

stained positive for these proteins. Specifically, DMT1 was scored

3 (intense staining) in 16 (Fig.

1E), TfR was scored 1 (light staining) in 12 (Fig. 1F), and FPN was scored 2 (moderate

staining) in 11 (Fig. 1G) OE

specimens. All three transporters were expressed at high levels in

CCC. Comparing the expression of the iron transport proteins in OE

and CCC specimens, we observed no remarkable difference in DMT1

expression (Fig. 1E), whereas

expression of TfR and FPN was significantly higher (P<0.001) in

CCC than in OE (Fig. 1F and

G).

Macrophages with englobed iron

infiltrate OE and CCC

Fig. 1 indicates

that iron ions flowed into and drained from cells. Iron was

deposited not only in epithelial cells but also in the stroma of

OE. Although Prussian blue staining revealed iron deposition in

macrophages located immediately below the epithelium, it was

difficult to ascertain whether iron ions in the entire stroma were

englobed by macrophages. Hence, we examined the distribution of

macrophages in the stroma to determine if they englobed iron ions

as well.

We detected the pan-macrophage marker CD68 in the

deep stroma layer, and the iron englobed macrophages below the

epithelium (Fig. 2A, CD68).

Immunohistochemical staining for CD11c (M1 macrophage marker),

CD163, and CD206 (M2 macrophage markers) markers revealed the

presence of CD11c+, CD163+, and

CD206+ cells immediately just below the OE epithelium,

and only M2 macrophages in the deep layer of the stroma (Fig. 2A, region within the dotted line).

Double staining for iron and CD163 revealed the presence of M2

macrophages englobed iron ions in the deep layer of the OE stroma

(Fig. 2A arrow). We located

significantly more CD163+ and CD206+ cells,

than CD11c+ cells in the deep layer of OE (Fig. 2C, P<0.001). CD68+

cells, along with conspicuous staining of CD163+ and

CD206+ cells, were observed in the stroma of CCC tumors

(Fig. 2B). We also observed

macrophages with englobed iron (Fig.

2B arrow) and far more abundant M2 than M1 macrophages in CCC

specimens (Fig. 2D, P<0.001).

There were no statistically significant differences in the numbers

of cells positive for CD11c, CD163, and CD206 between OE and CCC

(data not shown).

| Figure 2Immunolocalization of CD68, CD11c,

CD163 and CD206. (A) Stroma under macrophages englobed with iron in

OE specimens designated as deep layer (region within the dotted

line). Distribution of CD68, CD11c, CD163 and CD206 in the deep

layer. Double staining for iron and CD163 shows M2 macrophages

englobed with iron in the stroma (arrows). The star (*) indicates

the lumen of OE. Magnification, x400. Scale bar, 50 µm. (B)

Distribution of CD68, CD11c, CD163 and CD206 in ovarian CCC

specimens. Double staining for iron and CD163 shows M2 macrophages

englobed with iron in the stroma of CCC (arrows). Magnification,

x400. Scale bar, 50 µm. Comparison of numbers of antibody-positive

cells in (C) OE and (D) CCC. **P<0.001 via

Steel-Dwass test (used after Kruskal-Wallis test). NS, not

significant; CCC, clear cell adenocarcinoma; OE, ovarian

endometrioma. |

Endometrial epithelium infiltrates the

stroma of OE

We postulated that the macrophages with englobed

iron in the deep layer of the OE stroma resulted from endometrial

epithelium infiltration of the OE stroma. We further hypothesized

that M2 macrophages colonized the epithelium and invaded the

stroma.

The endometrial epithelium forms rows in typical OE

(Fig. 3A). Fig. 2 demonstrates more abundant M2 than

M1 macrophages in the deep layers of the stroma (Fig. 3A; CD68, CD11c, CD163, and CD206 are

shown in Fig. 2A). The positive

rate of Ki67 (tumor growth marker) was low in the endometrial

epithelium (4.6%±1.6, Fig. 4A).

| Figure 3Keratin staining indicates

endometrial epithelium infiltration of the stroma. (A) Endometrial

epithelium of typical OE was used as a control. Endometrial

epithelium formed a row and was stained with keratin (region within

the black square in the H&E-stained figure; magnification,

x400). CD68+, CD11c+, CD163+ and

CD206+ cells below the epithelium and the deep stroma

layer (region within the dotted line). (B) Endometrial epithelium

of OE. Keratin staining in the area where endometrial epithelium

infiltrated stroma and formed lumens (region within the black

square in the H&E-stained figure; magnification, x400).

CD68+ cells around infiltrated epithelium. CD163 and

CD206 were stained more intensely than CD11c. (C and D) Endometrial

epithelium adjacent to ovarian CCC from two patients. Keratin

staining in the area where endometrial epithelium infiltrated the

stroma and formed lumens (region within the black square in

H&E-stained figure; magnification, x400). CD68+

cells surrounded infiltrated epithelium. CD163 and CD206 were

stained more intensely than CD11c. H&E staining magnification,

x100; scale bar, 200 µm. Other images magnification, x400; scale

bar, 50 µm. The star (*) indicates the lumen of OE. CCC, clear cell

adenocarcinoma; OE, ovarian endometrioma; H&E,

hematoxylin-eosin. |

Staining for the epithelial cell marker keratin

revealed the regions where the endometrium epithelium had

infiltrated the stroma and had formed lumens in one OE specimen

(Fig. 3B: Patient no. 1, region

within the black square in the H&E staining figure) and in two

CCC specimens with OE adjacent to CCC (Fig. 3C-D: Patient no.2-3, region within

the black square in the H&E staining figure). These regions

contained more abundant CD163+ and CD206+

cells than CD11c+ cells (Figs. 3B-D and S1, and Ki67 positive rate of 14.3-38.5%;

Patient no.1: 38.5±6.0%, Patient no. 2: 36.1±3.7%, Patient no. 3:

14.3±2.4% was observed in the endometrium epithelium infiltrating

the stroma (Fig. 4B-D).

Endometrium, as well as ovarian follicles, stained positive for

keratin. To avoid misinterpreting these findings as normal, we

distinguished endometrial epithelium from ovarian follicles using

CD10, a diagnostic marker of endometriosis (19). The endometrial stroma was positive,

while the follicular epithelium was negative for CD10 (Fig. S2).

Discussion

In the present study, we detected iron transporters

in OE and CCC using immunohistochemistry and identified M2

macrophages englobed with iron throughout the stroma of OE. The

endometrial epithelium infiltrating the stroma was highly

proliferative.

Although the precise mechanisms associated with the

carcinogenesis of EAOC remain under investigation, the

co-occurrence of the AT-rich interaction domain 1A (ARID1A) and the

phosphatidylinositol-4, 5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit

alpha (PIK3CA) mutation promotes CCC growth (20-23).

Moreover, an iron-rich environment contributes to cell

proliferation in OE, with oxidative stress and reactive oxygen

species implicated in DNA damage (8,10,23,24).

Thus, these findings suggest a relationship between iron and OE

tumorigenesis. However, the mechanisms through which endometrial

epithelium and tumor cells transport iron ions have remained

unknown. Therefore, we aimed to demonstrate iron flow using

immunohistochemistry. The transmembrane protein for ferric metal

iron, DMT1, plays a major role in the intestinal uptake of iron

ions (11). This protein is located

not only on the cell surface but also in endosomes (12), with TfR also located on the cell

surface. Because transferrin-binding trivalent iron molecules bind

TfR, the complex becomes internalized in cells via endocytosis

(12). Alternatively, FPN is the

only transporter that exports iron ions in humans (25). The iron-responsive element (IRE) and

iron regulatory proteins regulate DMT1, TfR, and FPN expression

(26,27). Hence, iron metabolism is strictly

controlled by these mechanisms. This control system collapses in

cancer, and the iron overload associated with cancer is largely due

to iron dysregulation (28).

Specifically, DMT1 expression is upregulated in colorectal cancer

as compared to healthy colons (29). Furthermore, the expression of TfR

and FPN is high and low in high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma,

respectively, implying storage of excess iron ions in cells within

this carcinoma type (30). The

present findings indicate the upregulation of DMT1 and

downregulation of TfR and FPN expression in OE. Moreover, the

levels of the iron transporters differed in CCC tissues. We also

verified that iron ions flow in and out of the endometrial

epithelium, indicating that the differential abundance of

transporters is associated with intercellular iron concentrations,

which participate in carcinogenesis.

Excessive iron was detected not only in the

endometrial epithelium but also in the stroma of OE, and M2

macrophages englobed iron ions in the stroma. Macrophages polarized

toward the M2 phenotype generally produce anti-inflammatory

cytokines and participate in tissue repair and angiogenesis

(15), whereas M1 macrophages

induce inflammatory cytokines and bactericidal activity. Therefore,

M2 macrophages are regarded as TAMs (15). These TAMs have been detected within

ascites from patients with ovarian cancer, where interaction

between tumor cells and M2 macrophages induced tumor progression

via signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)

(31). In agreement with these

findings, we detected more M2 than M1 macrophages in the stroma of

OE and CCC. Furthermore, we identified M2 macrophages englobed with

iron in the deep layer of OE stroma, which became a central focus

of the study. Considering that ovarian cancer is an epithelial

cancer, these M2 macrophages englobed with iron likely influence

epithelial carcinogenesis by infiltrating endometrial epithelium in

the stroma. The endometrial epithelium OE typically forms smooth

rows of cells (7,32). However, we demonstrate that

endometrial epithelium infiltrates and forms lumens within the

stroma. Moreover, the infiltrating epithelium was highly positive

for Ki67 compared with normal endometrial epithelium. This

indicates that the endometrial epithelium has potent proliferative

capacity, which is a state closer to cancer.

The infiltrative endometrial epithelium adjacent to

CCC is likely to be a precancerous lesion. However, infiltrative

endometrial epithelium in OE also has potential carcinogenic

capacity, as benign OE has loss-of-function mutations in ARID1A

like in CCC (33,34). Considering that OE harbors ARID1A

loss-of-function mutations, M2 macrophages in these regions might

accelerate carcinogenesis of the endometrial epithelium

infiltrating the stroma. We suggest that OE carcinogenesis occurs

not only in endometrial cysts but also in epithelium infiltrating

the stroma. Studies in a larger patient cohort are needed to verify

these findings. In a preliminary study, we performed an experiment

using an ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma cell line and identified

that TfR and DMT1 could be detected by western blotting. We thought

that we should conduct additional experiments using ovarian

endometrioma, ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma, and normal ovary

tissues as the study's primary aim was to compare between ovarian

endometrioma and ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Due to the lack

of ovarian endometrioma and normal ovary cell lines, we intend

further explore the role of iron transporters using an animal

model, where we will be able to access more tissue samples and

perform western blots. Nevertheless, our results provide insights

into a potential underlying mechanism of carcinogenesis from OE to

CCC while elucidating tumor growth features. Confirming these

findings using pathological specimens, we could recognize the

possibility of them being precancerous lesions. Moreover, careful

follow-up is needed for the prevention and early detection of CCC.

Further investigations of the mechanisms responsible for the

infiltration of the endometrial epithelium into the stroma are

warranted.

In summary, the present study discovered iron

transport proteins in the epithelium of OE and CCC tumor cells. We

also revealed M2 macrophages englobed with iron in the stroma of OE

and CCC. Epithelium invading the stroma of OE implies

carcinogenesis under the influence of M2 macrophages englobed with

iron. These findings offer a new perspective on the malignant

transformation of OE into EAOC, which may serve as a precancerous

index factor.

Supplementary Material

Number of cells positive for CD11c,

CD163 and CD206 in the endometrial epithelium-infiltrating stroma.

(A) Number of antibody-positive cells around the infiltrated

epithelium in (A) patient no. 1, (B) patient no. 2 and (C) patient

no. 3. The data are shown as the mean ± SD in 10 fields of

view.

Endometrial epithelium and ovarian

follicle infiltrated by OE stroma. CD10 staining of (A) ovarian

follicle and (B) endometrial stroma. (C) Keratin-stained epithelium

of ovarian follicle. Magnification, x400. Scale bar, 50 μm. OE,

ovarian endometrioma.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

KA, YN and HO contributed to study design. KA, YN,

TT and HO developed the methodology and assessed the authenticity

of the data. KA, YN and TT validated the data and performed formal

analysis. YN and TT provided resources. KA wrote the original

draft. KA, YN, TT and HO reviewed and edited the manuscript. HO

supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Institutional Review

Board of Tokyo Women's Medical University Hospital (approval no.

5371; Tokyo, Japan). Opt-out informed consent was obtained from all

patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Giudice LC and Kao LC: Endometriosis.

Lancet. 364:1789–1799. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Rogers PA, D'Hooghe TM, Fazleabas A,

Gargett CE, Giudice LC, Montgomery GW, Rombauts L, Salamonsen LA

and Zondervan KT: Priorities for endometriosis research:

Recommendations from an international consensus workshop. Reprod

Sci. 16:335–346. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, Lee A,

Near AM, Webb PM, Nagle CM, Doherty JA, Cushing-Haugen KL, Wicklund

KG, et al: Association between endometriosis and risk of

histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: A pooled analysis of

case-control studies. Lancet Oncol. 13:385–394. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Fukunaga M, Nomura K, Ishikawa E and

Ushigome S: Ovarian atypical endometriosis: Its close association

with malignant epithelial tumours. Histopathology. 30:249–255.

1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Machida H, Matsuo K, Yamagami W, Ebina Y,

Kobayashi Y, Tabata T, Kanauchi M, Nagase S, Enomoto T and Mikami

M: Trends and characteristics of epithelial ovarian cancer in Japan

between 2002 and 2015: A JSGO-JSOG joint study. Gynecol Oncol.

153:589–596. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Hooper G: The diagnosis and treatment of

endometriosis. Can Med Assoc J. 42:243–246. 1940.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Clement PB: The pathology of

endometriosis: A survey of the many faces of a common disease

emphasizing diagnostic pitfalls and unusual and newly appreciated

aspects. Adv Anat Pathol. 14:241–260. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Yamaguchi K, Mandai M, Toyokuni S,

Hamanishi J, Higuchi T, Takakura K and Fujii S: Contents of

endometriotic cysts, especially the high concentration of free

iron, are a possible cause of carcinogenesis in the cysts through

the iron-induced persistent oxidative stress. Clin Cancer Res.

14:32–40. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Fujimoto Y, Imanaka S, Yamada Y, Ogawa K,

Ito F, Kawahara N, Yoshimoto C and Kobayashi H: Comparison of redox

parameters in ovarian endometrioma and its malignant

transformation. Oncol Lett. 16:5257–5264. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Greenshields AL, Shepherd TG and Hoskin

DW: Contribution of reactive oxygen species to ovarian cancer cell

growth arrest and killing by the anti-malarial drug artesunate. Mol

Carcinog. 56:75–93. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Gunshin H, Mackenzie B, Berger UV, Gunshin

Y, Romero MF, Boron WF, Nussberger S, Gollan JL and Hediger MA:

Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled

metal-ion transporter. Nature. 388:482–488. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tabuchi M, Yoshimori T, Yamaguchi K,

Yoshida T and Kishi F: Human NRAMP2/DMT1, which mediates iron

transport across endosomal membranes, is localized to late

endosomes and lysosomes in HEp-2 cells. J Biol Chem.

275:22220–22228. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ross SL, Tran L, Winters A, Lee KJ, Plewa

C, Foltz I, King C, Miranda LP, Allen J, Beckman H, et al:

Molecular mechanism of hepcidin-mediated ferroportin

internalization requires ferroportin lysines, not tyrosines or

JAK-STAT. Cell Metab. 15:905–917. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Gammella E, Buratti P, Cairo G and

Recalcati S: The transferrin receptor: The cellular iron gate.

Metallomics. 9:1367–1375. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Mantovani A, Sozzani S, Locati M, Allavena

P and Sica A: Macrophage polarization: Tumor-associated macrophages

as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends

Immunol. 23:549–555. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Pollard JW: Tumour-educated macrophages

promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 4:71–78.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yamada Y, Uchiyama T, Ito F, Kawahara N,

Ogawa K, Obayashi C and Kobayashi H: Clinical significance of M2

macrophages expressing heme oxygenase-1 in malignant transformation

of ovarian endometrioma. Pathol Res Pract. 215:639–643.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Canet B, Pons C, Espinosa I and Prat J:

CDC42-positive macrophages may prevent malignant transformation of

ovarian endometriosis. Hum Pathol. 43:720–725. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Toki T, Shimizu M, Takagi Y, Ashida T and

Konishi I: CD10 is a marker for normal and neoplastic endometrial

stromal cells. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 21:41–47. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Chandler RL, Damrauer JS, Raab JR,

Schisler JC, Wilkerson MD, Didion JP, Starmer J, Serber D, Yee D,

Xiong J, et al: Coexistent ARID1A-PIK3CA mutations promote ovarian

clear-cell tumorigenesis through pro-tumorigenic inflammatory

cytokine signalling. Nat Commun. 6(6118)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Yamamoto S, Tsuda H, Takano M, Tamai S and

Matsubara O: Loss of ARID1A protein expression occurs as an early

event in ovarian clear-cell carcinoma development and frequently

coexists with PIK3CA mutations. Mod Pathol. 25:615–624.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Samartzis EP, Noske A, Dedes KJ, Fink D

and Imesch P: ARID1A mutations and PI3K/AKT pathway alterations in

endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. Int

J Mol Sci. 14:18824–18849. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Huang HN, Lin MC, Huang WC, Chiang YC and

Kuo KT: Loss of ARID1A expression and its relationship with

PI3K-Akt pathway alterations and ZNF217 amplification in ovarian

clear cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 27:983–990. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ray PD, Huang BW and Tsuji Y: Reactive

oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular

signaling. Cell Signal. 24:981–990. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Donovan A, Lima CA, Pinkus JL, Pinkus GS,

Zon LI, Robine S and Andrews NC: The iron exporter

ferroportin/Slc40a1 is essential for iron homeostasis. Cell Metab.

1:191–200. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Schümann K, Moret R, Künzle H and Kühn LC:

Iron regulatory protein as an endogenous sensor of iron in rat

intestinal mucosa. Possible implications for the regulation of iron

absorption. Eur J Biochem. 260:362–372. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Miyazawa M, Bogdan AR, Hashimoto K and

Tsuji Y: Regulation of transferrin receptor-1 mRNA by the interplay

between IRE-binding proteins and miR-7/miR-141 in the 3'-IRE

stem-loops. RNA. 24:468–479. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Miller LD, Coffman LG, Chou JW, Black MA,

Bergh J, D'Agostino R Jr, Torti SV and Torti FM: An iron regulatory

gene signature predicts outcome in breast cancer. Cancer Res.

71:6728–6737. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Xue X, Ramakrishnan SK, Weisz K, Triner D,

Xie L, Attili D, Pant A, Győrffy B, Zhan M, Carter-Su C, et al:

Iron uptake via DMT1 integrates cell cycle with JAK-STAT3 signaling

to promote colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell Metab. 24:447–461.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Basuli D, Tesfay L, Deng Z, Paul B,

Yamamoto Y, Ning G, Xian W, McKeon F, Lynch M, Crum CP, et al: Iron

addiction: A novel therapeutic target in ovarian cancer. Oncogene.

36:4089–4099. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Takaishi K, Komohara Y, Tashiro H, Ohtake

H, Nakagawa T, Katabuchi H and Takeya M: Involvement of

M2-polarized macrophages in the ascites from advanced epithelial

ovarian carcinoma in tumor progression via Stat3 activation. Cancer

Sci. 101:2128–2136. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Tran-Harding K, Nair RT, Dawkins A, Ayoob

A, Owen J, Deraney S, Lee JT, Stevens S and Ganesh H: Endometriosis

revisited: An imaging review of the usual and unusual

manifestations with pathological correlation. Clin Imaging.

52:163–171. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, Zhao Y,

Tse K, Zeng T, Senz J, McConechy MK, Anglesio MS, Kalloger SE, et

al: ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian

carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 363:1532–1543. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Yachida N, Yoshihara K, Suda K, Nakaoka H,

Ueda H, Sugino K, Yamaguchi M, Mori Y, Yamawaki K, Tamura R, et al:

ARID1A protein expression is retained in ovarian endometriosis with

ARID1A loss-of-function mutations: Implication for the two-hit

hypothesis. Sci Rep. 10(14260)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|