Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) accounts for 10% of all

hematologic malignancies and approximately 1% of all cancers

(1). It affects predominantly the

elderly and consists of a malignant proliferation of plasma cells

(PC). These malignant cells are mostly found inside the bone marrow

but they can also be present in extramedullary disease (ED)

(1,2). Plasma cells are responsible for

hypersecretion of M protein, which represents defective

immunoglobulin, and lead to a well-known association of symptoms

named CRAB-hypercalcemia, renal failure, anemia and bone lytic

lesions (2,3).

Pleural effusion (PE) in multiple myeloma is not an

uncommon finding, comprising about 6-14% of MM patients (4-6).

The most common causes of MM associated PE are congestive heart

failure, renal failure with or without nephrotic syndrome,

parapneumonic effusion and amyloidosis. Other causes can be

hypoalbuminemia, pulmonary embolism, secondary neoplasm and

lymphatic obstruction with chylothorax. In less than 1% of cases,

the effusion is a direct result of MM, designated as myelomatous

pleural effusion (MPE) (7).

Several mechanisms have been proposed for the pathogenesis of

pleural effusion in MM. They mostly originate from adjacent

skeletal or parenchymal tumors such as vertebral or pulmonary

plasmacytomas, direct pleural invasion by tumor nodules

(hematogenous dissemination) and mediastinal lymph node

infiltration with lymphatic blockage. The extramedullary spread can

be triggered by an invasive procedure (surgery or catheter

insertion) or by a bone fracture (8-11).

Rodriguez et al (12) established the diagnostic criteria

for MPE: Pleural fluid electrophoresis with monoclonal protein plus

atypical plasma cells in the pleural fluid plus histological

confirmation by pleural biopsy. Eighty percent of MPEs are

associated with IgA MM (13) and

present late in the course of the disease, carrying a poor

prognosis and a life expectancy of about 4 months. There is no

distinct therapy for the MPE and in some cases, palliative

pleurodesis is the only treatment possible (14).

Here we report an MPE associated with IgG/λ MM

presenting as a septic shock and renal failure requiring

hemodialysis in which a rare diagnosis was made after excluding all

other possible etiologies in a complex intensive care patient.

Case report

The authors describe the case of a 79-year-old white

woman, with IgG/λ MM, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus,

dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia. MM was diagnosed two months prior

admission (Fig. 1). At diagnosis,

the patient had an increase in total serum proteins (14.77 g/dl) at

the expense of an increase in γ-globulins (8.8 g/dl; 59.40%). The

measurement of serum immunoglobulins revealed an increase in the

concentration of heavy IgG chains (10,706.0 mg/dl) and free λ light

chains (2,720 mg/dl). Immunofixation revealed the presence of an

IgG/λ monoclonal gammopathy. At that time, medullary aspirate was

performed, which was very hypocellular (10.0x103/µl),

according to flow cytometry 10% of the cells were plasmocytes with

abnormal phenotypic characteristics CD38+,

CD138+, CD19-, CD56+,

CD10-, CD20-, CD117-,

CD45-.

She presented anemia and lytic bone lesions in the

skull. She started on oral melphalan and prednisolone. She was

classified as an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG)

Performance Status 1.

She was admitted to the emergency department in

March 2020 with symptoms of fatigue, severe bone pain, and

diarrhea. On admission, she presented with hemodynamic instability,

oliguric, and requiring oxygen through a face mask. Physical

examination revealed a decrease in breath sounds throughout the

right hemithorax. Complete blood count revealed anemia (Hb 8.1

g/dl), leukocytosis (12.7x109/l), neutrophilia

(11.3x109/l) and thrombocytopenia (35x109/l).

Chemistry panel revealed C-reactive protein 352.4 mg/l, creatinine

3.96 mg/dl and albumin of 1.83 g/dl. Arterial blood gas analysis

showed a type 1 respiratory insufficiency and hyperlactacidemia

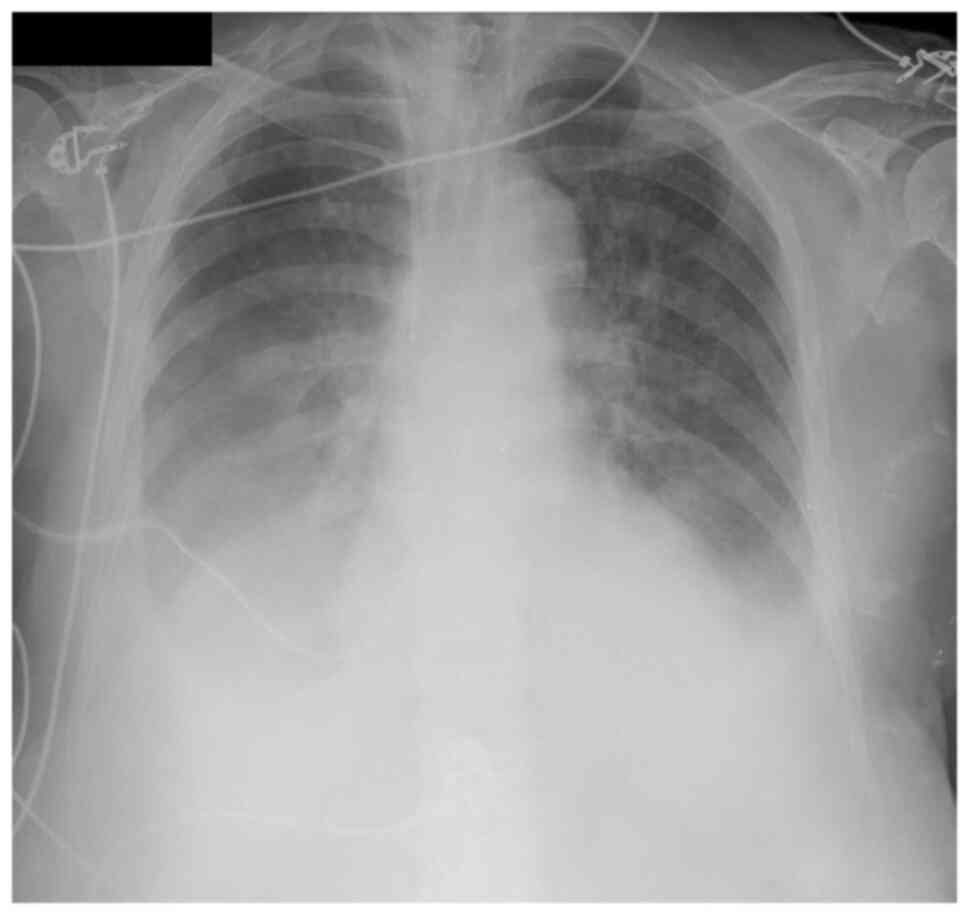

(4.9 mg/dl). The chest X-ray showed a bilateral pleural effusion

(Fig. 2). Diagnostic thoracentesis

was performed and the pleural fluid was compatible with an exudate

using Light's criteria (15).

She deteriorated and was admitted to the intensive

care unit for septic shock with multiorgan failure: renal,

hematological, neurological, cardiovascular and respiratory

failures. Blood and urine samples were withdrawn and sent for

microbiological analysis and she was started on broad-spectrum

antibiotics. Due to hypervolemia and acute renal failure, she was

put on sustained low-efficiency daily diafiltration (SLEDD) aimed

for a negative fluid balance. Despite all measures instituted, she

continued to deteriorate with dyspnea, tachypnea, desaturation, and

aggravated pleural effusion (Fig.

3).

The infectious etiology had been assumed as a most

likely cause for the pleural effusion. Despite diminishing

inflammatory parameters, pleural effusion enlarged causing

additional respiratory compromise. Other PE causes were also

addressed like renal failure and hypoalbuminemia. A detailed

systematic approach to investigate the etiology of this pleural

effusion was then undertaken.

Therapeutic thoracentesis was performed and 2,650 ml

of serosanguineous fluid was removed (Fig. 4). The pleural fluid analysis showed

pH 7.9, adenosine deaminase 31.7 U/l, and glucose 88 mg/dl,

proteins 3.5 g/dl, and LDH 618U/l. The ratio between pleural and

serum LDH was indicative of exudative pleural effusion. Protein

electrophoresis of pleural fluid showed a monoclonal γ-globulin

spike (1.2 g/dl, 34,2%) (Fig.

5).

| Figure 5Pleural fluid capillary

electrophoresis showing a γ-globulin spike (Alb, 36.7%; α1, 5.7%;

α2, 10.4%; β globulina, 11.0%; γ, 34.2%; pico monoclonal, 33.4%).

Alb, albumina; α1, α1 globulinal; α2, α2 globulina; β1, β1

globulina; β2, β2 globulina; γ, γ globulina. |

Flow cytometry showed 89% of abnormal PCs positive

for CD38 (low, decreased intensity comparatively to normal PC),

CD138, CD56 and CD117, and negative for CD10, CD19, CD20 and CD45.

Normal PC phenotype, for comparison: CD45+low,

CD38+high, CD138+, CD19+,

CD20-, CD56-, CD117- (16). The pleural fluid cells were stained

with an 8-color panel of fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal

antibodies specific for the aforementioned molecules, processed

with BD FACS™ lysing solution according to the manufacturer's

instructions (Becton Dickinson) and acquired using a BD FACSCanto™

II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Data generated as FCS files

were analyzed using the Infinicyt™ software (Cytognos). FSC and SSC

were captured on a linear scale (250 channels), and SSC was

represented with a mathematical transformation to expand the values

of the lower part of the scale for a better visualization of the

populations. For fluorescence parameters, a logarithmic

amplification was used, with logical transformation, allowing for a

resolution of 262 144 channels (~5.42 decades) (Fig. 6).

| Figure 6Flow cytometry dot plots showing 89%

of abnormal PCs in the pleural fluid (red dots), together with

neutrophils (black dots), lymphocytes (dark blue dots) and

monocytes/macrophages (blue dots). The abnormal PCs were positive

for CD38 (low, decreased intensity comparatively to normal PC),

CD138, CD56 and CD117, and negative for CD10, CD19, CD20 and CD45.

Normal PC phenotype, for comparison: CD45+low,

CD38+high, CD138+, CD19+,

CD20-, CD56-, CD117-. APC,

allophycocyanin; APC-H7, allophycocyanin-H7; FITC, fluorescein

isothiocyanate; FSC, forward scatter; KO, chrome orange; PCs,

plasma cells; PC5.5, phycoerythrin-cyanine 5.5; PC7,

phycoerythrin-cyanine 7; PE, phycoerythrin; SSC, side scatter. |

The cytological exam and immunocytochemical study

proved to be compatible with a plasma cell proliferation (Figs. 7 and 8). Bacteriological exam of the pleural

fluid revealed a multi-resistant Escherichia coli.

Histological confirmation on pleural biopsies, was deemed as

presenting with no benefit for the patient and was not performed. A

diagnosis of myelomatous pleural effusion with bacterial

overinfection was made.

Although respiratory insufficiency had improved, the

patient still degraded and the conditions to start MM induction

therapy were not met. Due to the poor prognosis of extramedullary

disease, particularly involving MPE, and the deterioration of

performance status of the patient, it was decided to withdraw

therapeutic measures and begin palliative care. The patient died 10

days after hospital admission.

Discussion

In the past few years, the incidence of EMD has

risen, probably due to the greater sensitivity of imaging tests but

also due to the increased survival of patients as a result of

advances in the therapeutic strategy of MM (17,18).

Evidence of extramedullary disease is a clear marker of poor

prognosis and the MPE is no exception. Even with aggressive

therapy, MPE has a progression-free survival and overall survival

of fewer than 4 months. The prognosis is even worst when the

mechanism involved in the progression of the disease is

hematogenous spread (17,19).

The patient had an ongoing infectious process, with

renal and cardiovascular failure combined with hypoalbuminemia, so

she had multiple factors for pleural effusion and they were much

more prevalent than MPE. There were no pulmonary or bone lesions

suggestive of plasmacytomas on chest X-ray. The initial approach to

pleural effusion was incomplete, probably due to a lack of clinical

suspicion, contributing to the delay in diagnosis.

Despite the existence of specific criteria,

diagnosing MPE remains a challenge. Pleural cytology has a

diagnosis rate for malignancy of around 60% (20). Blind pleural biopsy is a procedure

with associated risks and less attractive as a diagnostic tool,

since MPE affects the pleura irregularly. Nevertheless, pleural

fluid cytology or pleural biopsy provides the diagnosis of MPE in

approximately half of these patients (21,22).

Flow cytometry of pleural fluid is an excellent

complementary diagnostic method to the traditional strategy. It is

a fast, very sensitive and effective technique that allows not only

for plasma cell quantification but also for the identification of

phenotypically abnormal malignant plasma cells, thereby improving

the diagnosis of MPE. Its use is particularly relevant in

complementing the cytological assessment of serous fluids that lack

a predominance of plasma cells, or where these cells lack

definitive malignant morphological features (23). These characteristics add important

value to pleural fluid differential diagnosis. Thus, the authors

aim to warn of the need to review the MPE diagnostic criteria in

light of the current knowledge and available diagnostic tests.

Only a proper diagnosis will allow early

intervention. And despite the absence of aimed therapy for this

high-risk group of patients, the use of drugs, namely proteasome

inhibitors, (intravenous or intrapleural) has brought some hope in

the last few years (24). More

clinical trials are still needed in the future to better define the

correct strategy for these patients.

In conclusion, pleural effusion in patients with MM

is a heterogeneous entity that can arise from a varied number of

etiologies that require different treatments. A proper and complete

examination is essential in the diagnosis of MPE due to the

therapeutic and prognostic implications, including cytological

examination, protein electrophoresis with immunofixation, flow

cytometry and ultimately pleural biopsy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Luís Ramos Silva

(Department of Clinical Hematology, Hospital Center of São João,

4200-319 Porto, Portugal) and Professor Margarida Lima (Department

of Clinical Hematology-responsible for the cytometry and genetics

laboratories, University Hospital Center of Porto, 4099-901 Porto,

Portugal) for intellectual and technical assistance, and helping in

the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

ALR, MT and ASP contributed to the planning,

conduct, reporting, conception, design and acquisition of data, and

drafting the manuscript. JRB, CP and AP contributed to planning,

conduct, reporting, reporting, conception, design, and acquisition

of data and revision of the article. ALR, MT and ASP confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study involving a human subject was in

accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1975 as revised in 2000

and was approved by the Ethical Committee of University Hospital

Center of Porto, University of Porto (Porto, Portugal).

Patient consent for publication

The requirement for consent was waived and the study

was approved by the Ethical Committee of University Hospital Center

of Porto, University of Porto (Porto, Portugal).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Short K, Rajkumar S, Larson D, Buadi F,

Hayman S, Dispenzieri A, Gertz M, Kumar S, Mikhael J, Roy V, et al:

Incidence of extramedullary disease in patients with multiple

myeloma in the era of novel therapy, and the activity of

pomalidomide on extramedullary myeloma. Leukemia. 25:906–908.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Pileri SA, Harris

NL, Stein H, Siebert R, Advani R, Ghielmini M, Salles GA, Zelenetz

AD and Jaffe ES: The 2016 revision of the world health organization

classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 127:2375–2390.

2017.

|

|

3

|

Kyle RA and Rajkumar SV: Multiple myeloma.

N Engl J Med. 351:1860–73. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Byun JM, Kim KH, Choi IS, Park JH, Kim JS,

Shin DY, Koh Y, Kim I, Yoon SS and Lim HJ: Pleural effusion in

multiple myeloma: Characteristics and practice patterns. Acta

Haematol. 138:69–76. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wang Z, Xia G, Lan L, Liu F, Wang Y, Liu

B, Ding Y, Dai L and Zhang Y: Pleural effusion in multiple myeloma.

Intern Med. 55:339–345. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kintzer J, Rosenow EC III and Kyle RA:

Thoracic and pulmonary abnormalities in multiple myeloma. A review

of 958 Cases. Arch Intern Med. 138:727–730. 1978.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Oudart JB, Maquart FX, Semouma O, Lauer M,

Arthuis-Demoulin P and Ramont L: Pleural effusion in a patient with

multiple myeloma. Clin Chem. 58:672–674. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Bladé J, de Larrea CF, Rosiñol L, Cibeira

MT, Jiménez R and Powles R: Soft-tissue plasmacytomas in multiple

myeloma: Incidence, mechanisms of extramedullary spread, and

treatment approach. J Clin Oncol. 29:3805–3812. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Weinstock M and Ghobrial IM:

Extramedullary multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 54:1135–1141.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

De Larrea CF, Rosiñol L, Cibeira MT,

Rozman M, Rovira M and Bladé J: Extensive soft-tissue involvement

by plasmablastic myeloma arising from displaced humeral fractures.

Eur J Haematol. 85:448–451. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Alexandrakis MG, Passam FH, Kyriakou DS

and Bouros D: Pleural effusions in hematologic malignancies. Chest.

125:1546–1555. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Rodriguez J, Pereira A, Martínez JC, Conde

J and Pujol E: Pleural effusion in multiple myeloma. Chest.

105:622–624. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Shirdel A, Attaran D, Ghobadi H and Ghiasi

T: Myelomatous pleural effusion. Tanaffos. 6:68–72. 2007.

|

|

14

|

Iqbal N, Tariq MU, Shaikh MU and Majid H:

Pleural effusion as a manifestation of multiple myeloma. BMJ Case

Rep. 12(bcr2016215433)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Light RW: The light criteria: The

beginning and why they are useful 40 years later. Clin Chest Med.

34:21–26. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Bataiile R, Jégo G, Robillard N,

Barillé-Nion D, Harousseau JL, Moreau P, Amiot M and

Pellat-Deceunynck C: The phenotype of normal, reactive and

malignant plasma cells. Identification of ‘many and multiple

myelomas’ and of new targets for myeloma therapy. Haematologica.

91:1234–1240. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Touzeau C and Moreau P: How I treat

extramedullary myeloma. Blood. 127:971–976. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Varga C, Xie W, Laubach J, Ghobrial IM,

O'Donnell EK, Weinstock M, Paba-Prada C, Warren D, Maglio ME,

Schlossman R, et al: Development of extramedullary myeloma in the

era of novel agents: No evidence of increased risk with

lenalidomide-bortezomib combinations. Br J Haematol. 169:843–850.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Usmani SZ, Heuck C, Mitchell A, Szymonifka

J, Nair B, Hoering A, Alsayed Y, Waheed S, Haider S, Restrepo A, et

al: Extramedullary disease portends poor prognosis in multiple

myeloma and is over-represented in high-risk disease even in the

era of novel agents. Haematologica. 97:1761–1767. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Havelock T, Teoh R, Laws D and Gleeson F:

BTS Pleural Disease Guideline Group. Pleural procedures and

thoracic ultrasound: British thoracic society pleural disease

guideline 2010. Thorax. 65 (Suppl 2):ii61–ii76. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Kamble R, Wilson CS, Fassas A, Desikan R,

Siegel DS, Tricot G, Anderson P, Sawyer J, Anaissie E and Barlogie

B: Malignant pleural effusion of multiple myeloma: Prognostic

factors and outcome. Leuk Lymphoma. 46:1137–1142. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kim YJ, Kim SJ, Min K, Kim HY, Kim HJ, Lee

YK and Zang DY: Multiple myeloma with myelomatous pleural effusion:

A case report and review of the literature. Acta Haematol.

120:108–111. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Palmer HE, Wilson CS and Bardales RH:

Cytology and flow cytometry of malignant effusions of multiple

myeloma. Diagn Cytopathol. 22:147–151. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Iannitto E, Minardi V and Tripodo C: Use

of intrapleural bortezomib in myelomatous pleural effusion. Br J

Haematol. 139:621–622. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|