Introduction

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP), also known as

occult cancer, accounts for approximately 3-5% of all cancers and

is the fourth most common cause of mortality due to cancer in the

US (1,2). CUP is defined as a case of metastatic

cancer where the origination site cannot be determined (1). Median survival after CUP diagnosis is

approximately 3-4 months, with less than 25% of patients alive

after one year (1,2). Patients with CUP are categorized into

two prognostic subgroups according to their clinicopathologic

characteristics. The majority of patients with CUP (80-85%) belong

to unfavorable subsets (3). The

favorable risk cancer subgroup (15-20%) includes patients with

neuroendocrine CUP, peritoneal adenocarcinomatosis of a serous

papillary subtype, isolated axillary nodal metastases in females,

squamous cell carcinoma involving non-supraclavicular cervical

lymph nodes, single metastatic deposit from unknown primary and men

with blastic bone metastases and PSA expression (3). Very recently, new favorable subsets

of CUP seem to emerge including colorectal, lung and renal CUP

which underlies specific treatments (3).

Patients with CUP receive significantly less

treatment yet use more health services when compared to patients

with metastatic cancer of a known site (4). In the era of targeted therapies,

accurate histopathological and molecular classification of tumors

is essential to administer the best tailored therapeutic strategy

(5). Classifications based on

epigenetic alterations have served this purpose. Indeed, cancer

cells are characterized by a massive overall loss of DNA

methylation (20-60% overall decrease in 5-methylcytosine), and by

the simultaneous acquisition of specific patterns of

hypermethylation at CpG islands of certain promoters, which can

alter gene function, thereby contributing to cancer progression

(5).

Relatedly, pancreatic cancer accounts for

approximately 3% of all cancers and is the third most common cause

of mortality due to cancer in the U.S. (6). The most critical prognostic factor

for pancreatic cancer is stage at diagnosis (7). Median survival time after stage 1 and

stage 2 pancreatic cancer diagnosis is 4 months, with stage 3 and

stage 4 pancreatic cancer decreasing survival time to 2-3 months

(8). Approximately 53% of

pancreatic cancer patients are diagnosed after metastasis has

occurred (9). Since CUP and

metastatic pancreatic cancer are comparable in incidence and

survival outcome, there may be similarities in patient

characteristics of those initially misdiagnosed with CUP who

ultimately receive a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Definitive

diagnosis is crucial to the prognosis of patients diagnosed with

CUP, but studies examining characteristics of this outcome are

limited (10,11). Therefore, we sought to build upon

our previous research (12) to

examine patient characteristics associated with definitive

diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic cancer in older patients who

initially present with CUP.

Materials and methods

Study population

This retrospective cohort study uses 2010-2015

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare data, a

national population-based cancer registry linked to Medicare

claims. The cohort consisted of patients identified in the SEER

dataset diagnosed with CUP, International Classification of

Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3) codes C80.9 and

those diagnosed with stage 3 and stage 4 pancreatic cancer (ICD-O-3

codes C250-C259), between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2015.

Initial CUP diagnosis was defined by the date of the first biopsy

or date of ICD-O-3 diagnosis, whichever came first. Patients had to

be continuously enrolled in Medicare fee-for-service (both Part A

and B) beginning 1 year prior to diagnosis through the observation

period. Only the first reported primary cancer for each patient was

included, that is, this was the first time the patients had been

diagnosed with any type of cancer. Exclusion criteria were used to

maximize patients whose claims data were complete: patients were

excluded if enrolled in Medicare due to chronic disability, as well

as those diagnosed only on a death certificate, at autopsy, or in a

nursing home as their care was likely dissimilar to other patients.

Only claims paid by Medicare were included so as to avoid erroneous

billing codes. The final cohort consisted of 68,146 patients, of

which 17,565 were initially diagnosed with CUP prior to a

pancreatic cancer diagnosis.

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics included sex, age in four

groups (65, 66-74, 75-84, 85 and older), race [White, Black, and

Other (which included Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, Native

Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and Multi-racial; per the race

variable definition in the SEER data dictionary)], ethnicity

(Latino or Non-Latino; per the ethnicity variable definition in the

SEER data dictionary), area of residence (rural or urban), and

histology of the primary tumor (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell

carcinoma, epithelial/unspecified, and neuroendocrine). Comorbidity

was assessed utilizing the Klabunde adaptation of the Charlson

comorbidity score (13).

Definitive diagnosis

Odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI)

were calculated using two binary logistic regression models to

analyze the patient characteristics of who received definitive

diagnosis between the CUP-Pancreas group (those with an initial

diagnosis of CUP who eventually received a stage 3 or 4 pancreatic

cancer diagnosis) and the Pancreas group (those diagnosed with

stage 3 or 4 pancreatic cancer only). All analyses were conducted

using SAS, version 9.4 (Cary, NC).

Results

Patient characteristics

There were 68,146 patients who received a definitive

diagnosis of stage 3/4 pancreatic cancer between 2010-2015.

Approximately 74% were diagnosed with pancreatic cancer only

(n=50,581) and 26% started with an initial diagnosis of CUP

(n=17,565). The CUP-Pancreas group were 53.4% female, 37.3% were

between the ages of 75-84, 81.6% were White, 92.3% were non-Latino,

59.1% lived in an urban area, 42.6% had a Charlson comorbidity

score of 2 or higher, and 60.7% were histologically confirmed as

adenocarcinoma (Table I). Of the

cases diagnosed with pancreatic cancer only, characteristics were

generally similar to those initially diagnosed with CUP, however,

29.9% were between the ages of 75-84 and 31.9% had a Charlson

comorbidity score of 2 or higher.

| Table IDescriptive characteristics of

definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis in those initially diagnosed

with CUP compared to those diagnosed with pancreatic cancer only,

SEER-Medicare, 2010-2015. |

Table I

Descriptive characteristics of

definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis in those initially diagnosed

with CUP compared to those diagnosed with pancreatic cancer only,

SEER-Medicare, 2010-2015.

| Characteristic | CUP-pancreas

(n=17,565) (%) | Pancreas (n=50,581)

(%) |

|---|

| Sex | | |

|

Female | 9,387 (53.4) | 25,897 (51.2) |

|

Male | 8,178 (46.6) | 24,684 (48.8) |

| Age at diagnosis,

years | | |

|

65 | 2,025 (11.5) | 12,038 (23.8) |

|

66-74 | 6,031 (34.3) | 16,237 (32.1) |

|

75-84 | 6,553 (37.3) | 15,123 (29.9) |

|

85+ | 2,956 (16.9) | 7,183 (14.2) |

| Race | | |

|

White | 14,329 (81.6) | 41,122 (81.3) |

|

Black | 2,123 (12.1) | 5,564 (11.0) |

|

Other | 1,113 (6.3) | 3,895 (7.7) |

| Ethnicity | | |

|

Non-Latino | 16,212 (92.3) | 46,180 (91.3) |

|

Latino | 1,353 (7.7) | 4,401 (8.7) |

| Urban | | |

|

Yes | 10,379 (59.1) | 30,602 (60.5) |

|

No | 7,186 (40.9) | 19,979 (39.5) |

| Charlson comorbidity

score | | |

|

0 | 5,337 (30.4) | 21,649 (42.8) |

|

1 | 4,748 (27.0) | 12,797 (25.3) |

|

2+ | 7,480 (42.6) | 16,135 (31.9) |

| Histology | | |

|

Adenocarcinoma | 10,661 (60.7) | 29,843 (59.0) |

|

Epithelial

unspecified | 3,627 (20.6) | 11,077 (21.9) |

|

Neuroendocrine | 3,070 (17.5) | 9,105 (18.0) |

|

Squamous

cell carcinoma | 207 (1.2) | 556 (1.1) |

Definitive diagnosis of CUP-Pancreas

group

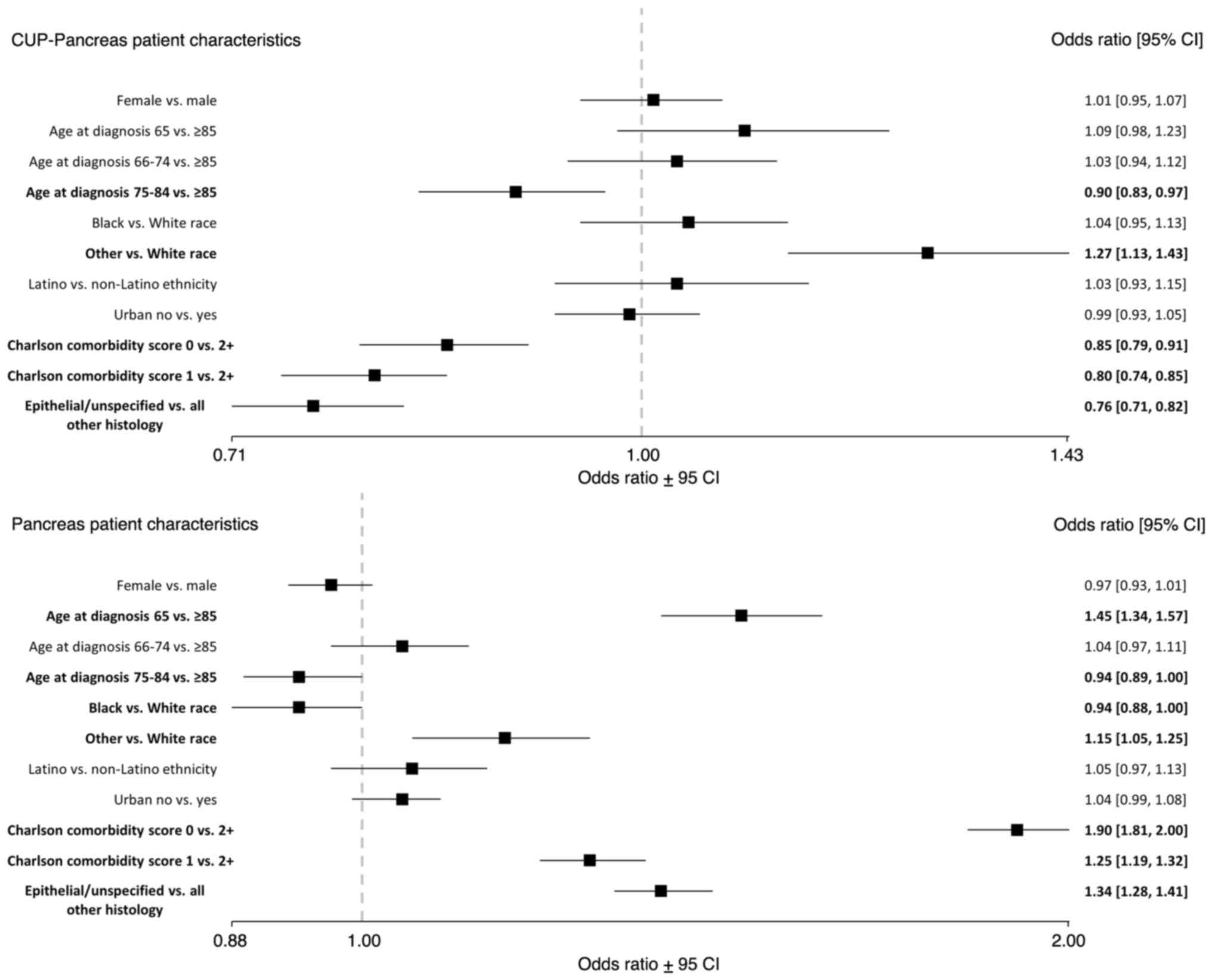

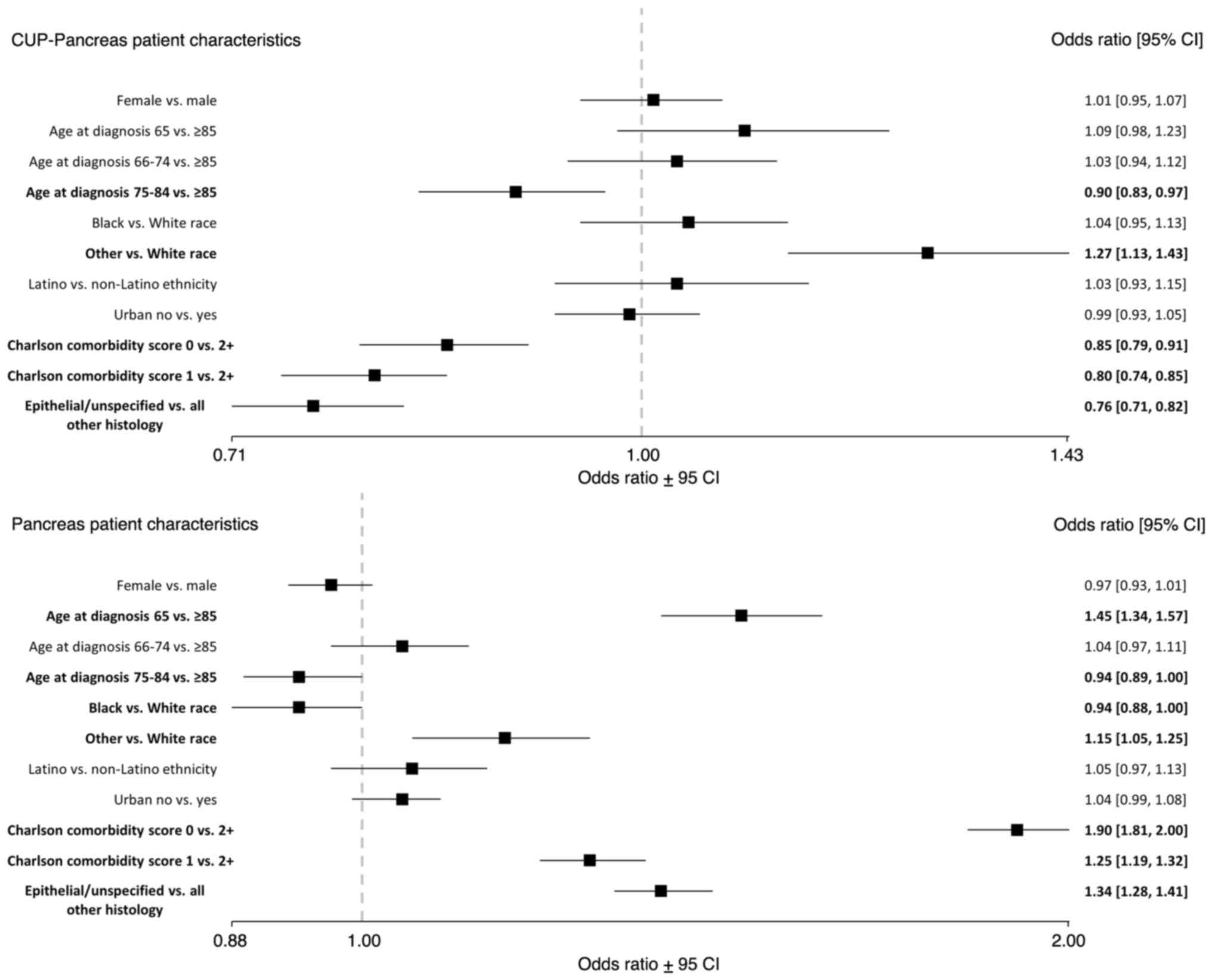

CUP patients between the ages of 75-84 had lower

odds of definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis [OR, 0.90 (0.83,

0.97)] compared to patients 85 years or older (Fig. 1). CUP patients had lower odds of

definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis for those with a Charlson

comorbidity score of 0 [OR, 0.85 (0.79, 0.91)] or 1 [OR, 0.80

(0.74, 0.85)] compared to a score of 2 or higher; and lower odds of

definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis for epithelial/unspecified

histology compared to all other histology types [OR, 0.76 (0.71,

0.82)]. CUP patients who identified as a race other than Black or

White had higher odds of definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis

[OR, 1.27 (1.13, 1.43)] compared to White patients.

| Figure 1ORs of definitive pancreatic cancer

diagnosis in those initially diagnosed with CUP (n=17,565) compared

to those diagnosed with pancreatic cancer only (n=50,581) by

patient characteristics, SEER-Medicare, 2010-2015. Bold indicates

statistical significance (P<0.05). CUP, cancer of unknown

primary; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SEER,

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results. |

Definitive diagnosis of pancreas only

group

Pancreatic only patients between the ages of 75-84

had lower odds of definitive diagnosis [OR, 0.94 (0.89, 1.00)]

compared to patients 85 years or older (Fig. 1). Pancreatic only patients who

identified as Black had lower odds of definitive diagnosis [OR,

0.94 (0.88, 1.00)] compared to White patients. Pancreatic only

patients of 65 years had higher odds of definitive diagnosis [OR,

1.45 (1.34, 1.57)] compared to patients 85 years or older.

Pancreatic only patients who identified as a race other than Black

or White had higher odds of definitive diagnosis [OR, 1.15 (1.05,

1.25)] compared to White patients; higher odds of definitive

diagnosis for those with a Charlson comorbidity score of 0 [OR,

1.90 (1.81, 2.00)] or 1 [OR, 1.25 (1.19, 1.32)] compared to a score

of 2 or higher; and higher odds for definitive diagnosis for

epithelial/unspecified histology compared to all other histology

types [OR, 1.34 (1.28, 1.41)].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based

study focusing on metastatic pancreatic cancer in patients

initially diagnosed with CUP. CUP patients had higher odds of

receiving a definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis if they

identified as a race other than Black or White. CUP patients had

lower odds of receiving a definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis if

they were older, had fewer or no comorbidities, and histology

confirmed as epithelial/unspecified. Patients with comorbidities

may receive health services more often than patients without

comorbidities, thus are more likely to come in contact with the

health care system (14). However,

older patients with comorbidities may be unable to complete the

diagnostic workup necessary to make a definitive diagnosis

(15). Characteristics associated

with delay of definitive diagnosis in CUP to a specified primary

site including older age, epithelial/unspecified histology, and

higher comorbid burden of disease correspond with current

scientific literature on CUP patterns of care, namely

population-based studies focusing on patient characteristics and

healthcare utilization (4,16,17),

adherence and diagnostic guidelines (10), and risk factors and clinical

management (18,19).

In patients diagnosed with stage 3 or stage 4

pancreatic cancer only, definitive diagnosis was similar to CUP

patients by race, however, this subpopulation was younger and had

fewer comorbidities overall. Furthermore, the comorbidity score and

whether histology was epithelial/unspecified were not barriers to

definitive diagnosis for the pancreatic cancer only group,

suggesting there are imbalances in delivery of care compared to

patients initially diagnosed with CUP. This is likely due to (a)

the complexity of identifying the primary tumor site in CUP,

whereas in identification of pancreatic cancer, the clinician at

least has a point from which to begin a well-informed diagnostic

process; and (b) poor performance status of the patient with CUP, a

potential confounder this study could not account for.

These findings further elucidate the health

disparities evident in CUP and pancreatic cancer diagnoses.

Scientific literature on cancer health disparities reports higher

incidence of metastatic pancreatic cancer among Black and Latino

patients, as well as lower occurrence of treatment (primarily

surgical intervention), poor access to quality health care, and

higher rates of overall morbidity and mortality (20-22).

An area of future research should focus on the patterns of care

associated with race, ethnicity, and social determinants of health

(to include socioeconomic status) in patients diagnosed with CUP

and pancreatic cancer, especially those in younger age groups given

increased incidence of pancreatic cancer in this population.

While SEER-Medicare data provided a robust sample

size, there are limitations in this study. Our study population was

limited to patients 65 years and older and did not include patients

with private insurance coverage. However, the age range of an

average patient with CUP is 80 years or older and the vast majority

of patients 65 years and older are insured through Medicare

(23). This study only

investigated patients with a final metastatic pancreatic cancer

diagnosis. It is also important to note clinicians may need to

report a definitive diagnosis to justify treatment for insurance

claims. Claims data for administrative and billing purposes might

be inaccurate from a biological or clinical disease

perspective.

There are significant deficiencies in the research

of other CUP-primary site cancers, for example ovarian and lung

cancers, as well as available studies comparing site-specific

therapy and empiric chemotherapy (24). These deficiencies include

limitations in recruitment methodology, study design, heterogeneity

among the CUP classifiers (e.g., epigenetic vs. transcriptomic

profiling), and incomparable therapies (24). An assessment of recently published

CUP literature recommends two comprehensive clinical trial designs

to address these limitations (24). Both designs are amenable to

implementing the latest diagnostics and therapeutic advances to

improve the quality of CUP research and the prognosis of many

patients (24).

This brief report discusses patient characteristics

associated with the definitive diagnosis of metastatic pancreatic

cancer in patients who initially presented with CUP based on a

large and representative population-based cohort. This profile

elucidates that about a quarter of patients who initially present

with CUP receive a definitive pancreatic cancer diagnosis and are

typically older with a higher burden of comorbidities. These

characteristics may contribute to delays in definitive diagnosis,

thereby negatively affecting survival and quality of life. Future

studies should focus on patterns of care and survival outcomes in

patients who initially present with CUP with other primary site

cancers.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of

Health (grant no. P30 CA042014-30).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are

available from the National Cancer Institute but restrictions apply

to the availability of these data, which were used under license

for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are

however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with

permission of the National Cancer Institute.

Authors' contributions

LLW was involved in study conceptualization, study

design, data management, data programming, formal analysis,

manuscript writing, manuscript review and editing, and funding

acquisition. JSG was involved in study conceptualization, data

management, data programming, manuscript review and editing, and

funding acquisition. LE was involved in study design, and

manuscript review and editing. ML was involved in formal analysis,

and manuscript review and editing. LLW and JSG confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethics approval was waived by the Institutional

Review Board at University of Nevada, Reno in view of the

retrospective nature of the study, citing SEER-Medicare data are

exempt [CFR 46.104(4)].

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

National Cancer Institute (NCI). Cancer of

unknown primary-health professional version. National Cancer

Institute, 2017. https://www.cancer.gov/types/unknown-primary/hp.

|

|

2

|

Pavlidis N and Pentheroudakis G: Cancer of

unknown primary site. Lancet. 379:1428–1435. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rassy E, Parent P, Lefort F, Boussios S,

Baciarello G and Pavlidis N: New rising entities in cancer of

unknown primary: Is there a real therapeutic benefit? Crit Rev

Oncol Hematol. 147(102882)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Schaffer AL, Pearson SA, Dobbins TA, Er

CC, Ward RL and Vajdic CM: Patterns of care and survival after a

cancer of unknown primary (CUP) diagnosis: A population-based

nested cohort study in Australian government department of

Veterans' Affairs clients. Cancer Epidemiol. 39:578–584.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Moran S, Martinez-Cardús A, Boussios S and

Esteller M: Precision medicine based on epigenomics: The paradigm

of carcinoma of unknown primary. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 14:682–694.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

American Cancer Society (ACS). Key

statistics for pancreatic cancer. American Cancer Society, 2020.

https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/about/key-statistics.html#references.

|

|

7

|

Henrikson NB, Aiello Bowles EJ, Blasi PR,

Morrison CC, Nguyen M, Pillarisetty VG and Lin JS: Screening for

pancreatic cancer: Updated evidence report and systematic review

for the US preventive services task force. JAMA. 322:445–454.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Khalaf N, El-Serag HB, Abrams HR and

Thrift AP: Burden of pancreatic cancer: From epidemiology to

practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 19:876–884. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Zhang Q, Zeng L, Chen Y, Lian G, Qian C,

Chen S, Li J and Huang K: Pancreatic cancer epidemiology,

detection, and management. Gastroenterol Res Pract.

2016(8962321)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sève P, Mackey J, Sawyer M, Lesimple T, de

La Fouchardière C, Broussolle C, Dumontet C and Ray-Coquard I:

Impact of clinical practice guidelines on the management for

carcinomas of unknown primary site: A controlled ‘before-after’

study. Bull Cancer. 96:E7–E17. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Pentheroudakis G, Stahel R, Hansen H and

Pavlidis N: Heterogeneity in cancer guidelines: Should we eradicate

or tolerate? Ann Oncol. 19:2067–2078. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Smith-Gagen J, Drake CM, White LL and

Pinheiro PS: Extent of diagnostic inquiry among a population-based

cohort of patients with cancer of unknown primary. Cancer Rep Rev.

3:2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Klabunde CN, Warren JL and Legler JM:

Assessing comorbidity using claims data: An overview. Med Care. 40

(8 Suppl):IV26–IV35. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Department of Health Pharmaceutical

Oncology Initiative (DHPOI). The impact of patient age on clinical

decision-making in oncology. London, UK: Department of Health,

2012.

|

|

15

|

Massarweh NN, Park JO, Bruix J, Yeung RS,

Etzioni RB, Symons RG, Baldwin LM and Flum DR: Diagnostic imaging

and biopsy use among elderly medicare beneficiaries with

hepatocellular carcinoma. J Oncol Pract. 7:155–160. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Schaffer AL, Pearson SA, Perez-Concha O,

Dobbins T, Ward RL, van Leeuwen MT, Rhee JJ, Laaksonen MA, Craigen

G and Vajdic CM: Diagnostic and health service pathways to

diagnosis of cancer-registry notified cancer of unknown primary

site (CUP). PLoS One. 15(e0230373)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jones W, Allardice G, Scott I, Oien K,

Brewster D and Morrison DS: Cancers of unknown primary diagnosed

during hospitalization: A population-based study. BMC Cancer.

17(85)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Rassy E and Pavlidis N: The currently

declining incidence of cancer of unknown primary. Cancer Epidemiol.

61:139–141. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Pavlidis N, Rassy E and Smith-Gagen J:

Cancer of unknown primary: Incidence rates, risk factors and

survival among adolescents and young adults. Int J Cancer.

146:1490–1498. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Noel M and Fiscella K: Disparities in

pancreatic cancer treatment and outcomes. Health Equity. 3:532–540.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Tavakkoli A, Singal AG, Waljee AK,

Elmunzer BJ, Pruitt SL, McKey T, Rubenstein JH, Scheiman JM and

Murphy CC: Racial disparities and trends in pancreatic cancer

incidence and mortality in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 18:171–178.e10. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zhou H, Zhang Y, Wei X, Yang K, Tan W, Qiu

Z, Li S, Chen Q, Song Y and Gao S: Racial disparities in pancreatic

neuroendocrine tumors survival: A SEER study. Cancer Med.

6:2745–2756. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Federal Interagency Forum (FIF) on

Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans: Key indicators of

well-being. U.S. Government Printing Office, 2015.

|

|

24

|

Rassy E, Labaki C, Chebel R, Boussios S,

Smith-Gagen J, Greco FA and Pavlidis N: Systematic review of the

CUP trials characteristics and perspectives for next-generation

studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 107(102407)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|