Introduction

Prostatic cancer is one of the most highly prevalent

malignancies affecting males globally (1). The spectrum of prostatic neoplasms

includes a variety of rare histological variants. Among these,

prostatic pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma (PGCC) is an extremely

rare and poorly understood subtype, recently listed in the World

Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Urinary

System as a variant of acinar adenocarcinoma (2,3). Based

on current data, PGCC is an aggressive form of acinar

adenocarcinoma associated with a poor prognosis, despite treatment

(4). PGCC typically demonstrates a

small portion of more differentiated, yet high-grade, typical

prostatic acinar adenocarcinoma (5).

It is characterized by giant, bizarre cells with pleomorphic nuclei

upon a conventional histological examination (2,3,6).

Some PGCC cases may also contain components of other

tumor types, such as squamous cell carcinoma, neuroendocrine

carcinoma and prostatic ductal adenocarcinoma (2). When compared to conventional prostate

carcinoma, PGCC frequently exhibits high Gleason grade

characteristics and currently falls into the International Society

of Urological Pathology (ISUP) grade group 5 (3,6,7), based on the recent 5th edition WHO

classification of male genital and urinary tumors (2). Moreover, previous chemotherapy,

hormonal therapy and radiation therapy are commonly related to

occurrences of PGCC, particularly androgen deprivation therapy

(3,8). Given its rarity, prostatic PGCC often

presents significant diagnostic and treatment challenges,

exacerbated by its aggressive nature and poor prognosis. The

scarcity of prostatic PGCC case reports in the medical literature

underscores the need for more comprehensive data on this rare

pathologic entity. The present study reports a case of a

65-year-old male patient with prostatic PGCC and also provides a

brief review of the literature with the aim of shattering further

light on this rare entity.

Case report

Patient information

A 65-year-old male patient visited Smart Health

Tower (Sulaimani, Iraq) and complained of severe dysuria, nocturia,

and frequent, urgent, and difficult urination for a period of 3

months. He had previously visited numerous urologists, and they

diagnosed his condition as benign prostatic hypertrophy with

prostatitis. He developed acute urinary retention while on medical

treatment for prostatitis. An 18 French Foley catheter was inserted

for him for 1 week; however, following its removal, the patient was

unable to urinate again. Consequently, the Foley catheter was

inserted again and kept for 2 months, being changed once every 2

weeks. Despite receiving multiple different types of antibiotics

and alpha-blockers, his condition remained the same. He then

complained of a generalized body ache, weakness, anorexia, weight

loss, constipation, back pain and insomnia with severe lower

urinary tract symptoms (LUTS).

Clinical examination

Upon an examination, the patient was found to be

pale, have a low body weight, and have a soft abdomen with

tenderness over the lower abdomen. His urine bag contained turbid

urine. A digital rectal examination revealed a significantly

enlarged and painful prostate bulging into the rectum, with a

smooth surface and no nodularity. The upper portion could not be

reached due to its large size.

Diagnostic assessment

Laboratory investigations, including a complete

blood count, renal function tests and prostate-specific antigen

(PSA), were performed and all yielded normal results. The patient

was sent for pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for more

detailed information about the prostate and pelvic organs. The

report of the pelvic MRI revealed a large prostatic mass measuring

9x9x11 cm with a well-defined outline and multiple areas of cystic

degeneration. Some of the cysts exhibited fluid-fluid levels

(indicating variably-aged internal hemorrhage). The mass originated

from the prostate with a marked pressure effect on the rest of the

prostate, urinary bladder and rectum. No definite invasion to the

surrounding organs and no associated pelvic lymphadenopathy were

observed. There was a focal bone lesion involving the left pubic

bone, suggestive of bone metastasis. A well-defined enhancing mass

was located in the left gluteal region under the gluteus maximus

muscle measuring 16x11 mm. The urinary bladder wall was thin and

there was no ascites. The case was presented to a multidisciplinary

team, which included urologists, general surgeons, radiologists,

pathologists and uro-oncologists; the decision was to perform a

prostate biopsy for tissue diagnosis. Following preparation, the

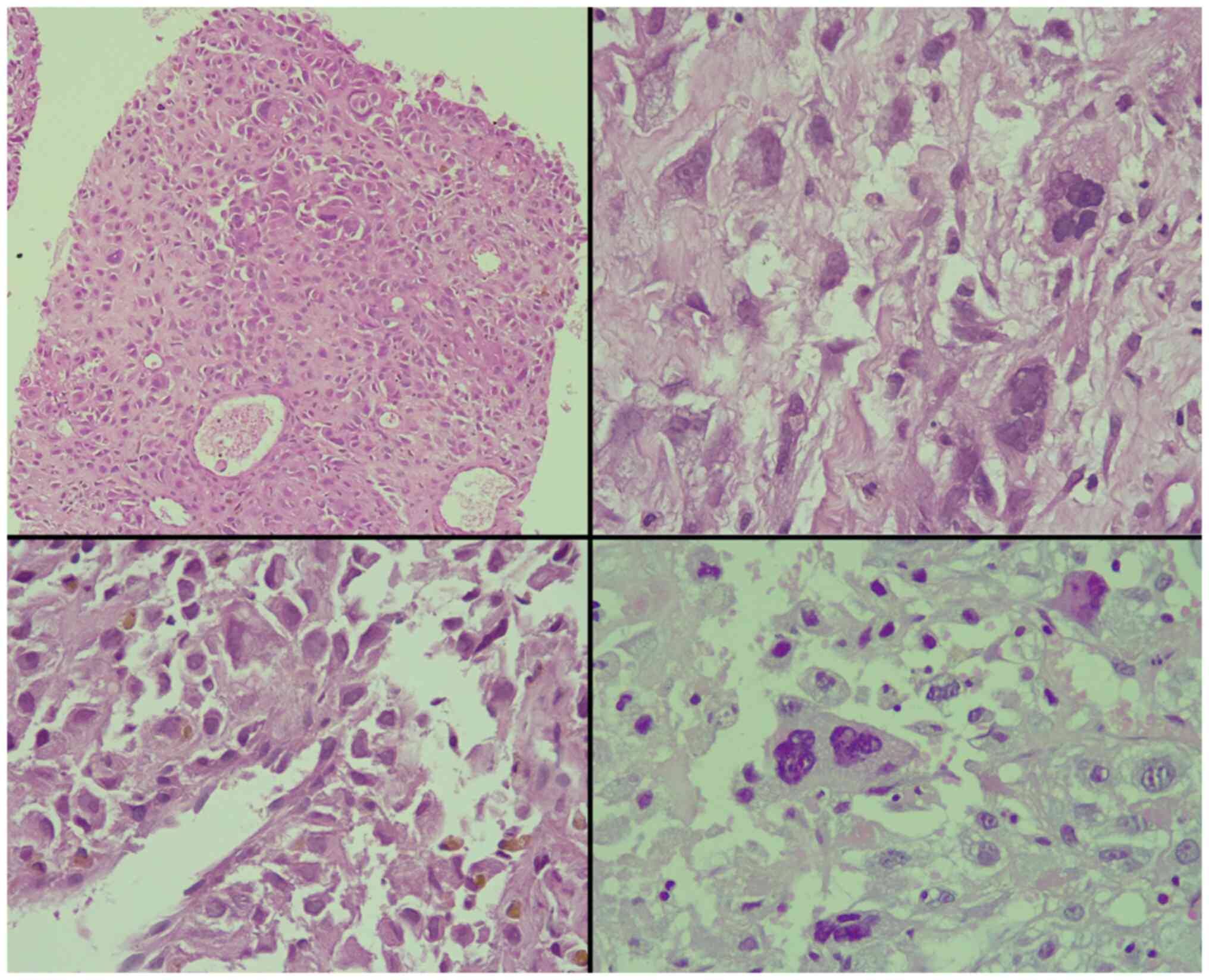

patient underwent a transrectal, 12-core prostate biopsy. Upon a

histopathological examination, it was found that 80% of the tissue

involved by the tumor had a Gleason score of 10 (5+5) for

conventional prostate carcinoma, composed of dyscohesive, large,

and pleomorphic cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and

bizarre, hyperchromatic nuclei with irregular nuclear outlines,

intranuclear inclusions, large macronucleoli and multinucleation

(Fig. 1). Perineural invasion was

observed; however, intraductal carcinoma, extraprostatic extension

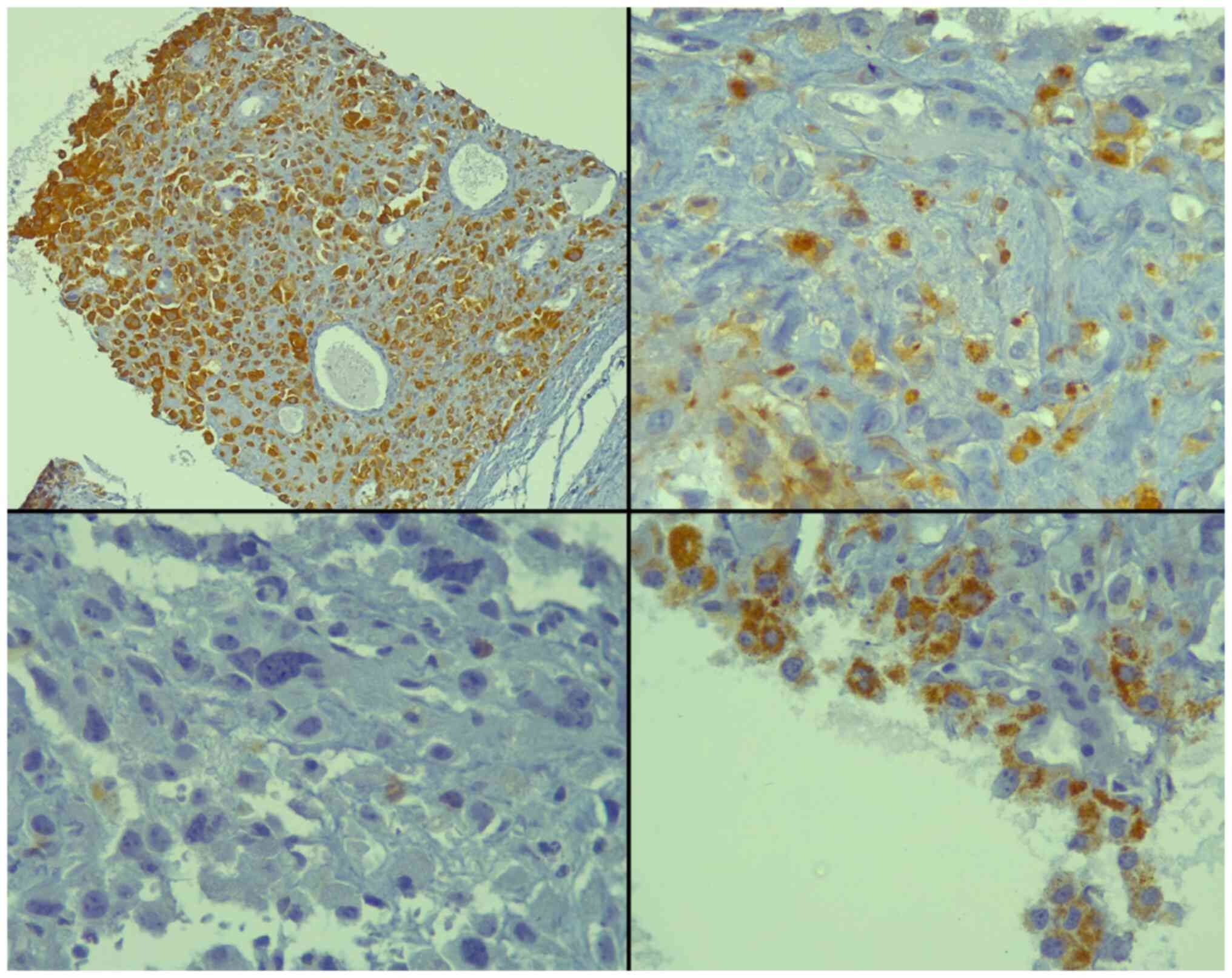

and lymphovascular invasion were not observed. An

immunohistochemical analysis revealed positivity of the tumor cells

for the pan-epithelial markers AE1/AE3 and alpha-methylacyl-CoA

racemase (AMACR), and focal positivity for sphingolipid activator

protein-2 (SAP) (Fig. 2). Of note,

all staining protocols and immunohistochemistry were conducted in

an external facility and not at the authors' institute. All the

other markers studied were negative, including PSA, melanin A,

desmin, CD34, CK7, CK20, caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2), GATA

binding protein 3 (GATA3) and thyroid transcription factor-1

(TTF-1) (data not shown). Hence, the diagnosis of PGCC of the

prostate was made.

Therapeutic intervention and

follow-up

While waiting for the results of the

histopathological examination of the prostate biopsy, the patient

developed acute abdominal distension and pain with repeated

vomiting, for which he was admitted to the emergency room

and was diagnosed with intestinal obstruction. Following 2 days of

conservative treatment (as at that time, the family refused any

surgical intervention, the gastrointestinal tract surgeon was

obliged to manage the patient by inserting a nasogastric tube,

antibiotics and IV fluid), the gastrointestinal tract surgeon

decided to do a laparotomy and end colostomy for him. After 4 days,

his condition deteriorated, and he developed severe sepsis with

wound dehiscence. He was admitted to the intensive care unit, and

after 2 weeks of follow-up, the patient passed away from multiorgan

failure.

Discussion

PGCC, a relatively rare tumor variant, has been

identified in several organs, including the hepatobiliary system,

pancreas, thyroid, urinary bladder, endometrium and kidney

(3,5,9). In the

context of the prostate, the first PGCC case was documented by Mai

et al in 1996(10). This

variant of carcinoma is interesting due to its unique histological

presentation and diagnostic challenges, particularly in

differentiating it from other forms of cancer.

Standard prostate cancer generally exhibits cells

that possess relatively uniform nuclei, even in high-grade cases

(7). This lack of pleomorphism

serves as a key characteristic that sets poorly differentiated

prostate cancer apart from urothelial carcinoma and allows for

differentiation from sarcomatoid carcinoma due to the absence of

spindle cells (3,5). However, in uncommon cases, the

histological features of pleomorphic giant cell adenocarcinoma of

the prostate can overlap with those of urothelial carcinoma, which

poses a diagnostic challenge, given that the treatments for these

two diseases are markedly different.

Clinically, determining whether a sizable tumor at

the bladder neck is of bladder or prostatic origin can be difficult

on imaging and even during cystoscopy. Experienced urologists have

submitted numerous cases of ‘bladder tumors’ that were initially

misdiagnosed by pathologists as urothelial carcinomas. Upon further

review and the implementation of immunohistochemistry, these tumors

were identified as high-grade prostatic adenocarcinomas (7). Previous reports of prostatic PGCC cases

(7,11) have detailed similarities to

conventional prostate cancer, including an aggressive clinical

course, an increased incidence in older patients, an association

with a high Gleason grade for standard prostate carcinoma

components, and typically focal, negative, or weak staining for

standard prostatic immunohistochemical markers (3).

Pleomorphic giant cell adenocarcinoma has very

particular histological features. The tumor cells display marked

pleomorphism and varying levels of cohesiveness. Even in the

presence of extreme atypia, more conventional features can still be

observed. If PGCC is associated with a more traditional acinar

adenocarcinoma, the latter component generally exhibits a high

Gleason grade, thereby categorizing this unique form of prostate

cancer under ISUP grade group 5, even in the absence of more

classical features (2,6,12). In

terms of morphology, PGCCs consist of unusually large cells that

typically comprise a small fraction of the overall tumor. These

cells are distinctively epithelial and form a cohesive structure,

which aids in distinguishing them from the diverse, pleomorphic

individual cells seen in sarcomatoid prostate adenocarcinoma

(7). Atypical mitoses are frequently

observed, and necrosis has been documented in the literature, with

the case reported by Larnaudie et al (13) illustrating hemorrhagic and necrotic

features. Another common observation is the clearing of the

cytoplasm, while spindle cell aspects have been described, albeit

being rare, as reported by Larnaudie et al (13). PGCC has been shown to be related to

other histological variants of prostatic carcinoma, including

squamous cell carcinoma, intraductal carcinoma and neuroendocrine

carcinoma (13). In the six cases

documented by Parwani et al (5), each one exhibited an additional

component of either small cell, squamous cell, or prostatic ductal

carcinoma. The tumor in the patient depicted herein displayed

clusters of loosely cohesive cells characterized by abundant

eosinophilic cytoplasm and large, hyperchromatic nuclei with

intranuclear inclusions, sizable macronucleoli and

multinucleation.

Diagnostic difficulties may arise when only the

pleomorphic component is present. The ability to recognize the

prostatic origin of the tumor is crucial, particularly in cases of

isolated metastasis, as the treatment modalities diverge

substantially, with one leaning towards hormonotherapy and

chemotherapy (13). To confirm the

origin of PGCC, the use of prostatic marker immunohistochemistry,

such as prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), PSA, NK3

homeobox 1 (NKX3.1) and androgen receptor, is recommended, as

previously suggested by Alharbi et al (7) and corroborated by Bilé-Silva et

al (4).

El-Zaatari et al (3) emphasized the importance of a

comprehensive panel of immunohistochemical markers for correct PGCC

diagnosis. Their review of 51 PGCC cases revealed that numerous

cases exhibited weak or no staining for any marker of prostatic

differentiation. Intriguingly, despite being commonly performed,

PSA staining was positive in only 2 out of 22 cases, whereas 10

cases exhibited weak and focal staining and the others were

entirely negative (3). The study by

Bilé-Silva et al (4) also

revealed a lower PSA positivity, ranging from 5 to 20%. However,

this low expression should not be construed as a negative PSA

expression, as it may result from various therapies (4). NKX3.1 emerged as a superior

prostate-specific marker for distinguishing urothelial carcinoma

and poorly differentiated prostatic adenocarcinoma, exhibiting a

high sensitivity and specificity for the latter (14). Yet, Alharbi et al.'s study

showed that its staining was not consistent, with some cases

showing only focal positivity or even negativity in the pleomorphic

component (7). Another promising

marker is homeobox B13 (HOXB13), exhibiting a high sensitivity and

specificity for prostatic tissue. A 2017 study suggested its

utility in confirming the prostatic origin of metastatic lesions

(13). However, the study by Alharbi

et al (7) revealed that

HOXB13 staining varied significantly among PGCC cases, with some

cases even showing complete negativity. The cases reported in the

study by Parwani et al (5)

were all positive for cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Lastly, the majority of

the PGCC cases in the study by Alharbi et al (7) exhibited negativity for GATA3, p63, and

thrombomodulin, which is useful for ruling out urothelial

carcinoma. All these findings emphasize the necessity for a

comprehensive panel of markers to ensure an accurate diagnosis of

PGCC. The case in the present study was positive for PSAP, AMACR,

and AE1/AE3, while being negative for PSA, CK7, CK20, GATA3,

melan-A, TTF-1, desmin, CD34 and CDX2.

Prior radiation, hormonal therapy, and chemotherapy

appear to be frequently associated with the PGCC phenotype

(4,8,15). There

is substantial evidence to indicate that PGCC develops as a result

of the dedifferentiation of high-grade, traditional prostate

carcinoma. The conventional prostatic adenocarcinoma component has

coexisted with all known PGCC cases. Notably, 11 out of 12 cases

with earlier traditional prostatic cancer, including the cases

reported in the study by El-Zaatari et al (3,5,6), had undergone radiation, chemo-, or

hormonal therapy prior to presenting with PGCC. This suggests that

prior treatment modalities may contribute to PGCC development

(3,5,7). This is

supported by observations of the frequent loss/weak staining of

prostatic differentiation markers in these tumors, pointing towards

a loss of prostatic differentiation (3). Further confirming this theory, the

study by Bilé-Silva et al (4)

demonstrated that all the patients with PGCC had previously been

treated with hormonal therapy.

The most recently published study by Bilé-Silva

et al (4), which included the

largest series of patients with extensive PGCC, provides a

comparative survival analysis between cases with PGCC and cases

with conventional high-grade prostate adenocarcinoma. The findings

indicate a significant difference in cancer-specific survival,

suggesting the aggressive nature of PGCC (4). This is also supported by the findings

of the cases reported by Alharbi et al (7).

Further research is required in order to confirm

these findings. Improving the understanding of this variant of

prostate cancer could allow for an earlier and more accurate

diagnosis, leading to more effective therapeutic approaches that

could potentially enhance patient outcomes.

In conclusion, PGCC of the prostate is an aggressive

variant with a dismal prognosis. It frequently occurs in patients

who have received prior prostatic cancer-directed therapy.

Prostatic marker immunohistochemistry, such as PSMA, PSA, NKX3.1

and androgen receptor can be used to confirm whether the PGCC is of

prostatic origin. The early recognition of this entity may

contribute to more effective therapy, as physicians could opt for

more aggressive treatments.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

SSF was a major contributor to the conception of the

study, as well as in the literature search for related studies. DMH

and FHK were involved in the literature review, in the writing of

the manuscript, and in the examination and interpretation of the

patient's data. FMF, SHM, BAA and HMR were involved in the

literature review, in the design of the study, in the critical

revision of the manuscript and in the processing of the figures.

RMA and AMA were the pathologists who performed the

histopathological diagnosis of the patient. BAA and FHK confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for his participation in the present study.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the

patient for the publication of the present case report and any

accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Mahmood ZH, Mohemed FM, Fatih BN, Qadir AA

and Abdalla SH: Cancer publications in one year (2022); a

cross-sectional study. Barw Med J. 1(Issue 2)2023.

|

|

2

|

Moch H, Amin MB, Berney DM, Compérat EM,

Gill AJ, Hartmann A, Menon S, Raspollini MR, Rubin MA, Srigley JR,

et al: The 2022 World Health Organization classification of tumours

of the urinary system and male genital organs-part A: Renal,

penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol. 82:458–468.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

El-Zaatari ZM, Thomas JS, Divatia MK, Shen

SS, Ayala AG, Monroig-Bosque P, Shehabeldin A and Ro JY:

Pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma of prostate: Rare tumor with

unique clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular

features. Ann Diagn Pathol. 52(151719)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Bilé-Silva A, Lopez-Beltran A, Rasteiro H,

Vau N, Blanca A, Gomez E, Gaspar F and Cheng L: Pleomorphic giant

cell carcinoma of the prostate: Clinicopathologic analysis and

oncological outcomes. Virchows Archiv. 482:493–505. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Parwani AV, Herawi M and Epstein JI:

Pleomorphic giant cell adenocarcinoma of the prostate: Report of 6

cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 30:1254–1259. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Lopez-Beltran A, Eble JN and Bostwick DG:

Pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma of the prostate. Arch Pathol Lab

Med. 129:683–685. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Alharbi AM, De Marzo AM, Hicks JL, Lotan

TL and Epstein JI: Prostatic adenocarcinoma with focal pleomorphic

giant cell features: A series of 30 cases. Am J Surg Pathol.

42:1286–1296. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Santoni M, Conti A, Burattini L, Berardi

R, Scarpelli M, Cheng L, Lopez-Beltran A, Cascinu S and Montironi

R: Neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer: Novel

morphological insights and future therapeutic perspectives. Biochim

Biophys Acta. 1846:630–637. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Samaratunga H, Delahunt B, Egevad L,

Adamson M, Hussey D, Malone G, Hoyle K, Nathan T, Kerle D, Ferguson

P and Nacey JN: Pleomorphic giant cell carcinoma of the urinary

bladder: An extreme form of tumour de-differentiation.

Histopathology. 68:533–540. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Mai K, Burns B and Morash D: Giant-cell

carcinoma of the prostate. J Urol Pathol. 5:167–174. 1996.

|

|

11

|

Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, Delahunt B,

Srigley JR and Humphrey PA: Grading Committee. The 2014

International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) consensus

conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: Definition of

grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am J Surg

Pathol. 40:244–252. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Alhamar M, Tudor Vladislav I, Smith SC,

Gao Y, Cheng L, Favazza LA, Alani AM, Ittmann MM, Riddle ND,

Whiteley LJ, et al: Gene fusion characterisation of rare aggressive

prostate cancer variants-adenosquamous carcinoma, pleomorphic

giant-cell carcinoma, and sarcomatoid carcinoma: An analysis of 19

cases. Histopathology. 77:890–899. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Larnaudie L, Compérat E, Conort P and

Varinot J: HOXB13 a useful marker in pleomorphic giant cell

adenocarcinoma of the prostate: A case report and review of the

literature. Virchows Archiv. 471:133–136. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Epstein JI, Egevad L, Humphrey PA and

Montironi R: ISUP Immunohistochemistry in Diagnostic Urologic

Pathology Group. Best practices recommendations in the application

of immunohistochemistry in the prostate: Report from the

International Society of Urologic Pathology consensus conference.

Am J Surg Pathol. 38:e6–e19. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Aparicio AM, Shen L, Tapia EL, Lu JF, Chen

HC, Zhang J, Wu G, Wang X, Troncoso P, Corn P, et al: Combined

tumor suppressor defects characterize clinically defined aggressive

variant prostate cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 22:1520–1530.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|