Introduction

Myxedema crisis is a decompensated form of

hypothyroidism associated with high mortality rates. The condition

is more common among females and the elderly. A notable proportion

of patients (39-51%) are diagnosed with hypothyroidism at their

presentation as myxedema crisis (1,2). Central

hypothyroidism accounts for 5-17% of patients presenting with

myxedema crisis (2,3). Sheehan's syndrome is a rare condition

characterized by panhypopituitarism due to post-partum pituitary

necrosis. Sheehan's syndrome presenting as a myxedema crisis is

extremely rare.

The present study describes the case of a patient

with Sheehan's syndrome with a first-time presentation as myxedema

crisis. Furthermore, the patient developed acute parkinsonism

during the recovery phase of the myxedema crisis, resulting in a

prolongation of the altered sensorium. Acute parkinsonism leading

to prolongation of the altered sensorium in a patient of myxedema

crisis has not been reported previously, at least to the best of

our knowledge.

Case report

A 31-year-old female patient presented with multiple

episodes of vomiting for 1 week and hypoactive delirium for 3 days.

The patient was evaluated at a local medical facility for the same

and was found to have hyponatremia. She was managed for

hyponatremia with 3% saline, but was referred to the Tertiary Care

Centre at Dr Rajendra Prasad Government Medical College Kangra at

Tanda (Kangra, India) due to the persistence of altered sensorium.

Upon evaluation, she was found to have a history of fever 1 week

prior. She had no history of headaches, abnormal body movements, or

weakness in any body part. Her previous history was significant,

with secondary amenorrhea and the failure of lactation following

the delivery of a child 11 years prior. The child was delivered at

home and there was no history of post-partum haemorrhage. At the

time of admission, the patient was drowsy with a Glasgow coma scale

of 11/15, had bradycardia (pulse rate-, 50 beats/min) and

hypotension (blood pressure, 84/50 mmHg). Her oral temperature was

91.5˚F (33.1˚C) and she had pallor. Upon a neurological

examination, the pupils were found to be bilaterally equal and

reacting to light. There was no facial asymmetry. Neck rigidity and

Kernig's sign were absent. There was a delayed relaxation of deep

tendon reflexes. Bilateral plantar reflexes were flexor. A

cardiovascular examination revealed bradycardia, although other

systemic examinations were within normal limits.

An analysis revealed that her haemoglobin level was

106 gm/l (normal range, 120-150 gm/l), the total leucocyte count

was 4.1x109/l (normal range, 4-10) and her platelet

count was 90,000/mm³ (range, 1.5-4.5 lakh); the differential counts

were: Polymorphs, 88%; lymphocytes, 10%; eosinophils, 1%;

monocytes, 1%; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 40 mm/1st hour;

random blood glucose, 4.662 mmol/l; urea, 7.14 mmol/l (normal

range, 4.64-16.06 mmol/l); creatinine, 33.5 µmol/l (normal range,

35.36-106.08 µmol/l); serum sodium, 120 mmol/l (normal range,

135-155 mmol/l); serum potassium, 4 mmol/l (normal range, 3.5-5.5

mmol/l); aspartate aminotransferase, 56 IU (normal range, 5-34 IU);

alanine aminotransferase, 53 IU (normal range, 6-40 IU); and

alkaline phosphatase, 73 IU (normal range, 15-112 IU). Scrub and

dengue serology were negative. HBsAg, hepatitis C virus and HIV

serology were non-reactive. The results of a urine examination,

chest X-ray and ultrasound abdomen were all within normal limits.

Her arterial blood gas analysis, cerebrospinal fluid examination

and electroencephalogram were within normal limits. Given her

history of altered sensorium, the delayed relaxation of deep tendon

reflexes, bradycardia and hyponatremia, myxedema crisis was

suspected and her myxedema score was calculated. Her myxedema score

was 75, suggesting myxedema crisis. Thyroid function tests revealed

that T3 was <0.616 nmol/l (normal range, 1.08-3.14 nmol/l), T4

was 39.12 nmol/l (normal range, 64.35-141.57 nmol/l) and thyroid

stimulating hormone (TSH) was 1.14 mIU/l (normal range, 0.550-4.780

mIU/l), suggestive of secondary hypothyroidism as opposed to sick

euthyroid syndrome. Since there was a history of lactation failure,

secondary amenorrhea and the delayed relaxation of deep tendon

reflexes, the possibility of secondary hypothyroidism was kept.

Samples for the pituitary hormonal profile were sent and management

for the myxedema crisis was initiated. The patient was managed with

oral levothyroxine 500 µg stat followed by 100 µg once daily

through a Ryle's tube, hydrocortisone infusion, intravenous fluids,

injectable antibiotics and rewarming. Her pituitary hormonal

profile was suggestive of panhypopituitarism [prolactin, 76.08

pmol/l (normal range, 145.21-1,161.73 pmol/l); adrenocorticotropic

hormone, 1.30 pmol/l (normal range, 1.58-13.92 pmol/l); cortisol,

108.98 nmol/l (normal range, 120.18-626.75 nmol/l); luteinising

hormone, 5.4 IU/l (normal range, 1.9-12.5 IU/l); follicle

stimulating hormone, 3.11 IU/l (normal range, 3.85-8.78 IU/l); and

estradiol, 36.71 pmol/l (normal range, 71.58-528.62 pmol/l)]. The

hormonal profile of the patient is presented in Table I. The patient exhibited an

improvement in bradycardia, hypotension and hyponatremia over the

ensuing 4 days; however, there was no improvement in the altered

sensorium. She was awake, but not able to speak or move her limbs.

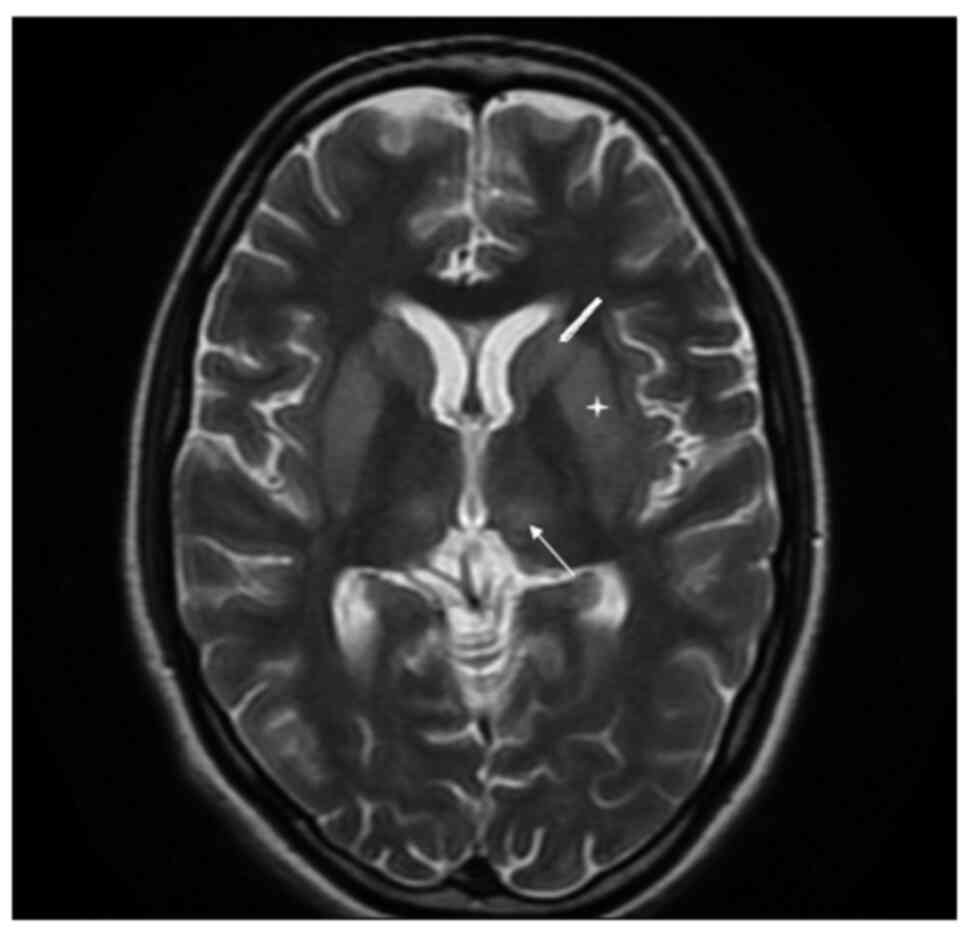

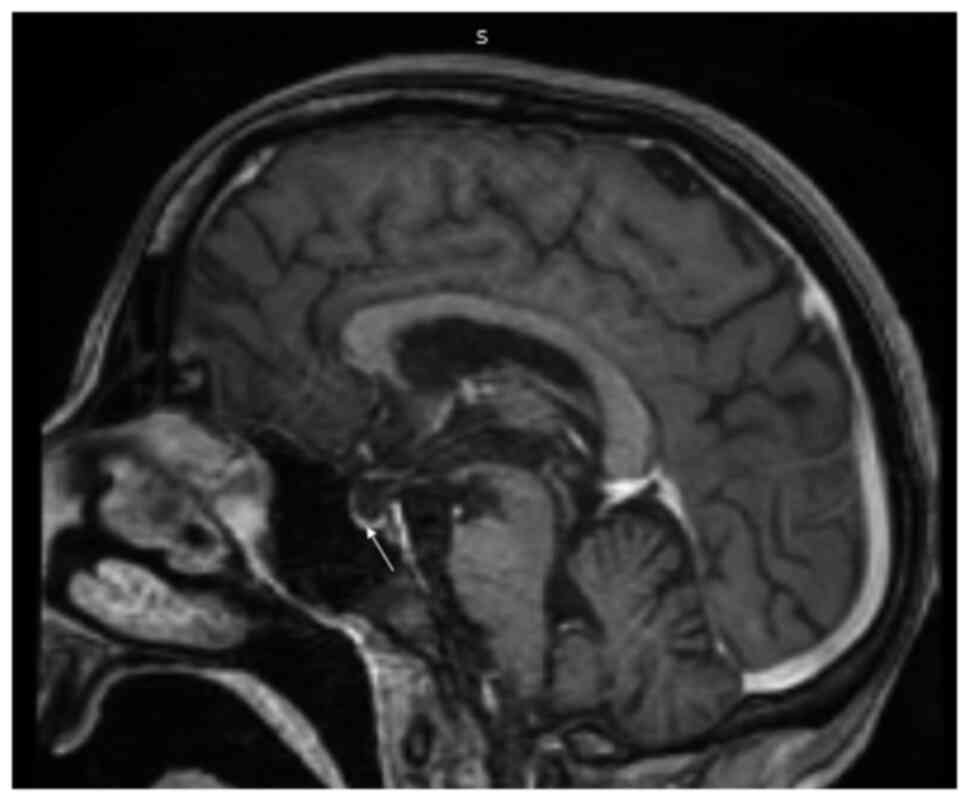

A repeat neurological examination was performed, which revealed

cogwheel rigidity and paraparesis. The possibility of acute

parkinsonism was kept. Magnetic resonance imaging of the sella and

brain was suggestive of an empty sella and extrapontine

myelinolysis (Figs. 1 and 2), substantiating the diagnosis of

Sheehan's syndrome with acute parkinsonism. The patient was

commenced on levodopa/carbidopa following which there was a partial

improvement in symptoms. She was discharged on oral hydrocortisone,

levothyroxine, ethinyl estradiol and progesterone, and

physiotherapy was recommended. At the 6th month of follow-up, the

patient was communicating well, the paraparesis had improved and

she could perform all household activities.

| Table IHormonal profile of the patient in the

present case report. |

Table I

Hormonal profile of the patient in the

present case report.

| Parameter | Patient value | Reference range |

|---|

| T3 | <40 ng/dl | 70-204 ng/dl |

| T4 | 3.04 µg/dl | 5-11 µg/dl |

| TSH | 1.14 µIU/ml | 0.550-4.780

µIU/ml |

| Prolactin | 1.75 ng/dl | 3.34-26.72 ng/ml |

| ACTH | 5.9 pg/ml | 7.2-63.3 pg/ml |

| Cortisol | 3.95 µg/dl | 4.3-22.4 µg/dl |

| LH | 5.4 mIU/ml | 1.9-12.5 mIU/ml |

| FSH | 3.11 mIU/ml | 3.85-8.78 mIU/ml |

| Estradiol | 10 pg/ml | 19.5-144 pg/ml |

Discussion

Sheehan's syndrome is characterised by the

development of hypopituitarism due to post-partum pituitary

necrosis. Severe post-partum haemorrhage leads to an impairment in

the blood supply of the physiologically enlarged pituitary gland

during pregnancy, culminating in pituitary necrosis. Owing to the

improvement in obstetrical care, Sheehan's syndrome is currently

rare in developed countries, but is still frequently encountered in

developing nations. In addition, it is more frequently encountered

with home deliveries as compared to institutional deliveries

(4). Although post-partum

haemorrhage is the most critical factor determining the development

of Sheehan's syndrome, other factors, such as genetic

susceptibility and autoimmunity also play a role. Growth hormone

deficiency is the most common deficiency observed in different

studies (5-8).

However, data regarding prolactin and TSH deficiencies are

variable. Although previous studies have reported prolactin

deficiency to be more frequent, a study in India observed TSH

deficiency to be more common (9).

Chronic Sheehan's syndrome typically has non-specific features such

as easy fatigability, lassitude, giddiness, etc., and thus often

remains undiagnosed for years. The first-time presentation of

Sheehan's syndrome in the emergency room as a myxedema crisis is

rare. In a previous study with a cohort of 23 patients of myxedema

crisis, 3 patients had Sheehan's syndrome as the aetiology of

hypothyroidism (1).

Myxedema crisis is an under-recognised differential

of patients visiting the emergency department with an altered

sensorium. The most critical part of the management of a myxedema

crisis is the timely suspicion of diagnosis and early initiation of

treatment (2). Hyponatremia is a

common metabolic abnormality in the emergency room and can itself

present as an altered sensorium. Hence, the suspicion of myxedema

crisis in the setting of hyponatremia, particularly when the

patient has not previously been diagnosed with hypothyroidism,

becomes difficult. The absence of features of frank hypothyroidism

in secondary hypothyroidism due to TSH-independent secretion of

levothyroxine, further adds to the difficulty (10). Moreover, the thyroid profile in

secondary hypothyroidism is similar to sick euthyroid syndrome,

which can be seen in critically ill patients of any aetiology. The

history of lactation failure and secondary amenorrhea in the

patient described herein was the key to the suspicion of secondary

hypothyroidism. The presence of a multitude of features like

hyponatremia, hypotension, bradycardia, hypothermia, etc. in a

patient of altered sensorium indicates towards the diagnosis of

myxedema crisis in such a setting. The use of myxedema score >60

aids in the confirmation of diagnosis (11).

Extrapontine myelinolysis (EPM) as a cause of

persistent altered sensorium during the recovery phase of myxedema

crisis has not been reported previously, at least to the best of

our knowledge. Persistent altered sensorium in a patient with

myxedema crisis can be due to electrolyte abnormalities,

cerebrovascular accident, septic encephalopathy, myxedema psychosis

and slow recovery in the elderly. Extrapontine myelinolysis occurs

due to a rapid osmotic shift and usually develops 7-14 days

following an acute insult (12).

Alcoholism, malnutrition, cirrhosis and severe burns are

well-recognized predisposing factors for the development of EPM

(13). However, hypocortisolism as a

predisposing factor for EPM has only recently been recognized

(14). Although the rapid correction

of hyponatremia of any aetiology can lead to EPM, chances increase

in the setting of undiagnosed hypocortisolism. Rapid steroid

replacement in the setting of hypocortisolism along with the

correction of hyponatremia by 3% saline can add to damage due to a

steep rise in sodium levels. The patient in the present study had a

history of secondary amenorrhea and lactation failure; however,

Sheehan's syndrome was not suspected at her initial medical

contact. Thus, the case in the present study also reiterates the

importance of a basic history and clinical examination, while

treating an electrolyte imbalance. In general, demyelination is

associated with a poor prognosis with the persistence of morbidity

following treatment. However, EPM associated with hypocortisolism

has been shown to have a more favourable outcome, as observed in

the patient described herein (15).

In conclusion, the present study describes a case

with the first-time presentation of Sheehan's syndrome as a

myxedema crisis. Sheehan's syndrome remains prevalent in developing

countries and should be suspected in females with a history of

lactation failure and secondary amenorrhea especially with home

delivery. The present case report reiterates the importance of

basic history and clinical examination, while treating an

electrolyte imbalance and exercising caution during correction. The

timely suspicion of myxedema crisis in patients presenting with an

altered sensorium in the emergency room remains the most crucial

part of managing the condition. Furthermore, the case described

herein highlights the importance of being vigilant during the

recovery phase of a myxedema crisis, and considering alternative

causes if altered sensorium persists.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as

no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current

study.

Authors' contributions

RG wrote the initial draft of the manuscript and

contributed to patient management. SC edited and finalised the

draft of the manuscript and contributed to patient management. VS

helped in editing the manuscript and contributed to patient

management. NSC helped in editing the manuscript and contributed to

the radiology-related patient management. NC helped in editing the

manuscript and contributed to patient management. DK helped in

editing the manuscript and contributed to patient management. All

authors have read and approved final version of the manuscript. RG

and SC confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent for participation was

obtained from the patient.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was

obtained from the patient for the publication of the present case

report and any related images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Dutta P, Bhansali A, Masoodi SR, Bhadada

S, Sharma N and Rajput R: Predictors of outcome in myxoedema coma:

A study from a tertiary care centre. Crit Care.

12(R1)2008.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Chaudhary S, Das L, Sharma N, Sachdeva N,

Bhansali A and Dutta P: Utility of myxedema score as a predictor of

mortality in myxedema coma. J Endocrinol Invest. 46:59–65.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Wartofsky L: Myxedema coma. Endocrinol

Metab Clin North Am. 35:687–698, vii-viii. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Zargar AH, Singh B, Laway BA, Masoodi SR,

Wani AI and Bashir MI: Epidemiologic aspects of postpartum

pituitary hypofunction (Sheehan's syndrome). Fertil Steril.

84:523–528. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Diri H, Tanriverdi F, Karaca Z, Senol S,

Unluhizarci K, Durak AC, Atmaca H and Kelestimur F: Extensive

investigation of 114 patients with Sheehan's syndrome: A continuing

disorder. Eur J Endocrinol. 171:311–318. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Gokalp D, Alpagat G, Tuzcu A, Bahceci M,

Tuzcu S, Yakut F and Yildirim A: Four decades without diagnosis:

Sheehan's syndrome, a retrospective analysis. Gynecol Endocrinol.

32:904–907. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kelestimur F, Jonsson P, Molvalilar S,

Gomez JM, Auernhammer CJ, Colak R, Koltowska-Häggström M and Goth

MI: Sheehan's syndrome: baseline characteristics and effect of 2

years of growth hormone replacement therapy in 91 patients in

KIMS-Pfizer international metabolic database. Eur J Endocrinol.

152:581–587. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lim CH, Han JH, Jin J, Yu JE, Chung JO,

Cho DH, Chung DJ and Chung MY: Electrolyte imbalance in patients

with Sheehan's syndrome. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 30:502–508.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Laway B, Misgar R, Mir S and Wani A:

Clinical, hormonal and radiological features of partial Sheehan's

syndrome: An Indian experience. Arch Endocrinol Metab. 60:125–129.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Brent GA and Weetman AP: Hypothyroidism

and thyroiditis. In: Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Melmed S,

Koenig R, Rosen C, Auchus R and Goldfine A (eds). 14th edition.

Elsevier, Philadelphia, PA, p423, 2020.

|

|

11

|

Popoveniuc G, Chandra T, Sud A, Sharma M,

Blackman MR, Burman KD, Mete M, Desale S and Wartofsky L: A

diagnostic scoring system for myxedema coma. Endocr Pract.

20:808–817. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

John TM, Jacob CN, Xavier J, Kondanath S,

Ittycheria CC and Jayaprakash R: A case of acute onset

parkinsonism. Qatar Med J. 2013:29–32. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Singh TD, Fugate JE and Rabinstein AA:

Central pontine and extrapontine myelinolysis: A systematic review.

Eur J Neurol. 21:1443–1450. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Imam YZ, Saqqur M, Alhail H and Deleu D:

Extrapontine myelinolysis-induced parkinsonism in a patient with

adrenal crisis. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2012(327058)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Perikal PJ, Jagannatha AT, Khanapure KS,

Furtado SV, Joshi KC and Hegde AS: Extrapontine myelinolysis and

reversible parkinsonism after hyponatremia correction in a case of

pituitary adenoma: Hypopituitarism as a predisposition for osmotic

demyelination. World Neurosurg. 118:304–310. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|