Introduction

The outcome of surgically managed chronic subdural

hematoma (CSDH) is usually improved, with a median surgical

intervention-to-resolution time achieved until 160 days

(interquartile range, 85-365 days) (1-3).

However, the reappearance of hematoma occurs in up to 33% of

patients, which is related to higher morbidity and mortality rates

(4-10).

The primary pathogenetic mechanisms of the condition remain

uncertain; however, there is evidence of an interaction connecting

inflammatory, fibrinolytic and angiogenic pathways (2,3).

Numerous studies have recognized possible clinical, radiological

and surgical risk factors for the recurrence of hematomas,

including an advanced age, the male sex and other characteristics

inherent to the hematoma (4-6,10-12).

In extremely old patients suffering from multiple major

comorbidities, there are extensive repercussions, suggesting that

those at an older age are at a higher risk of developing recurrent

hematomas (4). A variety of

neurological symptoms frequently arise, ranging from mild focal

symptoms related to the long tracts to coma and mortality (2,3). The

diagnosis is typically complete with a computed tomography (CT)

scan of the head, which illustrates the hematoma and provides brain

compression (2,3).

Surgical hematoma evacuation constitutes the gold

standard for the recurrence of CSDH (2,3,13,14).

Drugs such as steroids, statins and tranexamic acid have been used

as adjunctive therapy to diminish the risk of reappearance.

Εqually, middle meningeal artery embolization (MMAE) recently gave

hopeful outcomes in recurrent cases (13,15-19).

Neuroedoscopy helps determine the adhesions in compartmentalized

lesions (20,21), while the role of membranectomy

remains to be established (22).

The present study describes the case of an elderly

male patient with refractory CSDH who was treated on an escalated

basis. In addition, after reviewing the relevant literature, the

complexity of refractory CSDH and all major available treatment

alternatives are discussed. Finally, the present study attempted to

identify the patient's ‘point of no return’, if any.

Case report

An 85-year-old male patient presented to the

University Hospital of Larissa (Larissa, Greece) in April, 2023 for

the first time complaining of increasing headaches and instability

while walking. The medical records of the patient mentioned

anticoagulant therapy (clopidogrel, 75 mg per day) for stroke

prevention by atrial arrhythmias (propafenone, 150 mg per day) and

diabetes type II (gliclazide, 60 mg per day). A clinical

examination revealed mild left hemiparesis [4/5 muscle strength

according to the Medical Research Council (MRC) Scale for Muscle

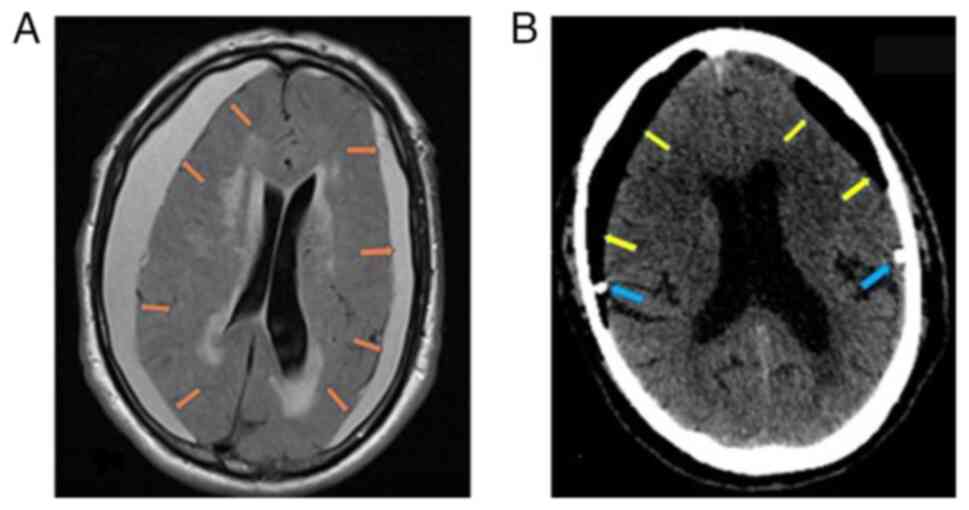

Strength], slow thinking ability, and mild disorientation. Magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain reealed bilateral subdural

hematomas that compressed the brain parenchyma (Fig. 1A). The patient underwent hematoma

evacuation through burr holes and a closed drainage system. The

post-operative head CT scan revealed complete hematoma evacuation,

and on the 2nd post-operative day, the patient could walk

unassisted without any neurological deficit (Fig. 1B).

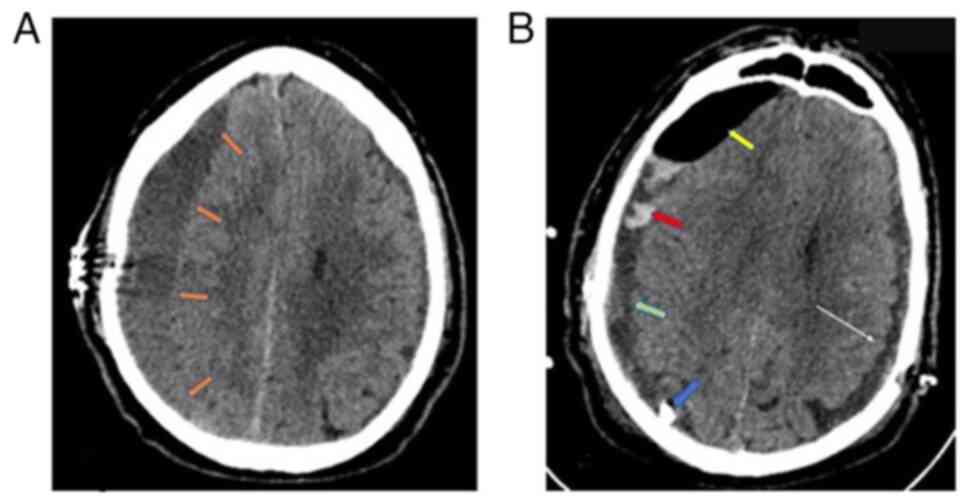

After 2 weeks, the patient returned to the hospital

with a recurrence of symptoms and a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score

of 13/15 (M:5, V:5, E:3), left hemiparesis and profound

disorientation. The new head CT scan revealed a recurrence of the

right subdural hematoma, which was again evacuated through a new

burr hole, now placed rostrally, and a closed drainage system

(Fig. 2A). In addition, in order to

prevent recurrence intraoperatively, the thick neomembranes that

were removed and a small amount of CSDH that was entrapped were

identified. The neurological status of the patient again completely

improved, while the post-operative head CT scan revealed partial

hematoma evacuation, which was treated conservatively with steroids

[dexamethasone was administered orally in a dose of 80 mg three

times a day for 1 week starting at the end of the first

post-operative week, and then gradual reduction of the dose (20 mg

at a time) every 5 days]. (Fig. 2B).

Based on a personalized management, it was decided to administer

dexamethasone as an add-on treatment for hematoma recurrence and

the option for MMAE was discussed; however, the patient did not

attend his regular follow-up.

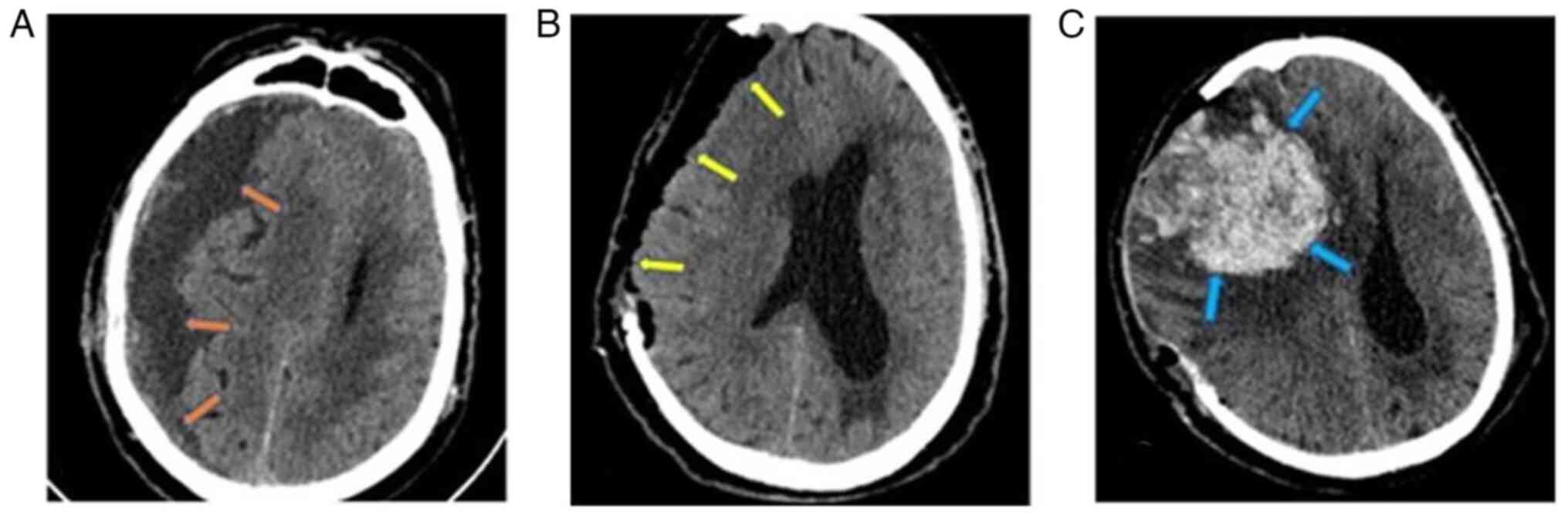

Subsequently, 1 month later, the patient was

admitted to the Emergency Room of the University Hospital of

Larissa comatose with a GCS score of 6/15 (motor response, 4;

verbal response, 1; eye-opening, 1). A new head CT scan revealed a

large recurrent subdural hematoma with a significant midline shift

(1.45 cm) (Fig. 3A). Considering the

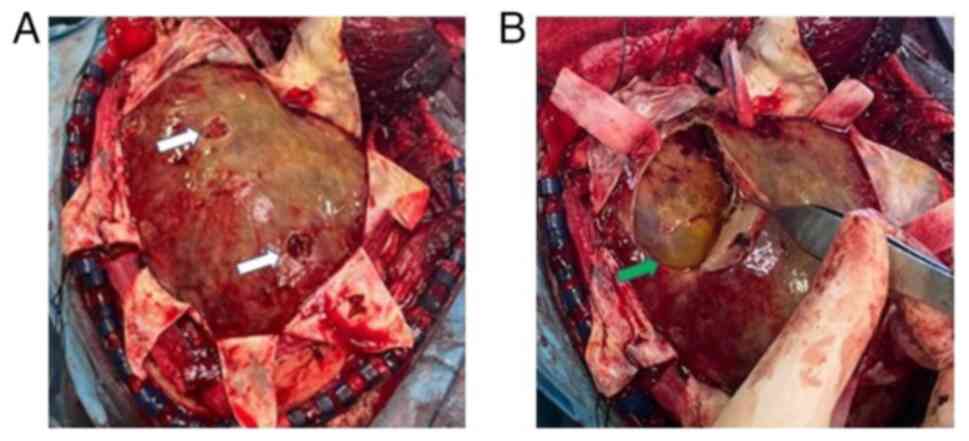

history of the patient, he underwent a decompressive craniectomy

for hematoma removal. After opening the dura, multiple layers of

hard neomembranes trapping a small amount of yellowish fluid in

numerous pockets were found (Fig.

4). Therefore, the neomembranes were removed and appropriate

hemostasis was performed, followed by layer-by-layer surgical wound

closure. An immediate post-operative CT scan revealed complete

hematoma removal and midline shift improvement (0.8 cm) (Fig. 3B), and the patient was transferred to

the intensive care unit for gradual awakening.

On the 2nd post-operative day, the patient exhibited

anisocoria (right, 5 mm; left, 2 mm), which soon changed to

fixed-and-dilated pupils and a tense skin flap of the craniectomy.

The final head CT scan revealed an extensive intraparenchymal

hemorrhage on the right side with a midline shift of 2 cm and a

trapped ipsilateral ventricle (Fig.

3C). At the request of the legal representative of the patient,

no further surgical intervention was performed, and the patient

succumbed within 48 h.

Discussion

The present case report demonstrates that a

relatively benign lesion, such as CSDH, may occasionally exhibit

very malignant behavior despite adequate treatment. The malignant

nature of CSDH in the case described herein became apparent with

the repeated recurrences, the subsequent intraparenchymal

hemorrhage, and eventually, the demise of the patient. It is

essential to re-consider several clinical and radiological

parameters throughout the disease course to identify the ‘point of

no return’, if any.

Risk factors

Zhu et al (12) performed a network meta-analysis on

the patient-related risk factors that are associated with an

increased risk of hematoma recurrence. The patient had several of

these predictors. Epidemiological risk factors included an advanced

age [standardized mean difference, 0.10; 95% confidence interval

(CI), 0.01-0.18], the male sex [relative risk (RR), 1.32; 95% CI,

1.50-1.51] and bilateral location (1.41; 1.20-1.67) (12). The radiological characteristics of

the original hematoma did not warn of an increased risk of

recurrence, as it was a type 1 lesion (hypodense; RR, 0.79;

0.59-1.05) and not a type 2 lesion (hyperdense, laminar, separated

and graded) (12).

Primary management

Neurosurgeons may opt between single burr hole

craniostomy (BHC), double BHC, twist drill craniostomy (TDC) and

minicraniotomy to remove CSDH; however, each of these has its own

recurrence and reoperation profiles (12,14).

There is evidence to suggest that double BHC is the most effective

approach (12). In addition, the

recurrence rate after BHC has been shown to be lower than after

minicraniotomy [odds ratio (OR), 0.58; 95% CI, 0.35-0.97] (15). Another meta-analysis by Yagnik et

al (14) revealed no difference

in the recurrence rate between BHC and TDC (OR, 1.16; 95% CI,

0.84-1.62); however, TDC was associated with a higher reoperation

rate, particularly when negative suction drainage was not used

(14). Zhu et al (12) highlighted the importance of

intraoperative saline irrigation (RR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.19-0.63) and

the use of a closed drainage system (RR, 0.45; 0.33-0.60) in

reducing the risk of hematoma recurrence. In the patient in the

present study, a single BHC was used with warm saline irrigation

and a closed drainage system on both sides. Han et al

(23) reported that the lack of

brain re-expansion was the strongest predictor of hematoma

recurrence (OR, 25.91; 95% CI, 7.11-94.35) and was strongly

associated with senile brain atrophy (OR, 2.36; 1.36-4.11)

(23,24). However, the post-operative head CT

scan revealed that the brain of the patient never re-expanded

sufficiently.

Management of the first

recurrence

According to Henry et al (13), when the symptoms recurred, he

hematoma was more complex, with a width >20 mm (OR, 2.37; 95%

CI, 1.56-3.60) and a midline shift >10 mm (OR, 1.61; 95% CI,

1.17-2.22). Therefore, it was decided to re-evacuate the hematoma

through a second BHC, which was connected to a closed drainage

system.

Steroids, statins and their combinations have been

proposed as medical adjuncts to reduce hematoma recurrence

(17,25). The effect of statins and steroids is

hypothesized to be mediated by their immunomodulatory properties

(25). According to Zhu et al

(12), patients receiving

atorvastatin (OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.14-0.69) and corticosteroids (OR

0.41; 95% CI, 0.24-0.70) had a lower hematoma recurrence rate. On

the contrary, Monteiro et al (16), based on a meta-analysis of seven

studies, found insufficient evidence to recommend the regular use

of statins (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.35-1.81) in CSDH. In two previous

meta-analyses of 12 and five trials, respectively, the authors

reported a lower recurrence rate with steroids (OR, 0.39; 95% CI,

0.19-0.79 and RR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.28-0.58), but at a higher

incidence of adverse events (RR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.71-4.28), including

psychiatric symptoms (RR, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.83-5.64), and no

difference in neurological outcomes (RR, 1; 95% CI, 0.93-1.08),

infection rate (RR, 1.86; 95% CI, 0.56-6.14) and all-cause

mortality (RR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.2-2.18) (26,27).

Considering all the available evidence, based on a personalized

management, in the present study, it was decided to administer

dexamethasone as an add-on treatment for hematoma recurrence and

discussed the option for MMAE.

MMAE is considered to reduce the risk of recurrence

by interrupting blood supply to the dura, thereby minimizing

leakage through the high permeability neomembranes (18,19). It

can be used in patients with previously untreated CSDH (upfront

MMAE), following surgical hematoma evacuation in cases without any

evidence of recurrence (prophylactic MMAE), and for recurrent CSDH

after prior surgical excision (18,19).

Currently, there is insufficient evidence to indicate that MMAE

reduces the risk of recurrence (18,19).

Management of the second

recurrence

In the present study, in the second recurrence, the

poor neurological status, significant mass effect, and the failure

of previous attempts mandated an urgent decompressive craniectomy.

Intraoperatively, the thick neomembranes that were removed and a

small amount of CSDH that was entrapped were identified. The role

of membranectomy, both inner and outer, or only outer, is still

debated (22). An outer

membranectomy allows for the uninhibited expansion of the brain by

eliminating the mass effect from the neomembranes and reducing the

risk of re-bleeding, while inner membranectomy allows for the

unimpeded circulation of cerebrospinal fluid through dural

lymphatics (22). Hacıyakupoğlu

et al (22) used craniotomy

and membranectomy to treat 13 patients with recurrent CSDH with

good results and no recurrence after 3 months.

Endoscopically-assisted burr hole hematoma

evacuation offers a safe and effective alternative to craniotomy

(20,21,28). A

flexible neuroendoscope is inserted through one or two burr holes

in the frontal and/or occipital regions (28). Under direct vision, the trabeculae

are transected, the compartments of the hematoma cavity are united,

and the contents are flushed out with body-warm saline (28). If microhemorrhages occur, a bipolar

microcatheter is used for hemostasis (28). Any residual hematoma is drained

through a closed-tube system (28).

There is recent evidence to indicate that neuroendoscopy reduces

recurrence rates compared with conventional treatment (13.1 vs.

3.1% with plain BHC, P<0.001); however, the mortality, morbidity

and functional rates remain relatively unaltered (21). In addition, the need for special

instruments and training in the use of neuroendoscopy seems to

limit its broad usage, as in the case described herein.

Intraparenchymal hemorrhage

The patient in the present study experienced a

massive intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH) with a fatal outcome on

the 2nd post-operative day. IPH is a rare, yet serious complication

following CSDH evacuation (29). In

a previous literature review by Krueger et al (29), 48 cases were described. IPH

frequently occurs in males (85%), with CSDH causing a significant

midline shift (54%), at ~1.9 days (±3 days) after surgery (29). The hemorrhage is usually located in

the hemisphere ipsilateral (P=0.02) to the hematoma (29). Several interrelated mechanisms,

including altered venous circulation, rapid re-expansion of the

brain and local edema, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of

hemorrhage (29). A second

intervention is required in ~27% of cases, with mortality rates

reaching as high as 25% (29).

Point of no return

Table I estimates the

probability of hematoma recurrence for each of the aforementioned

parameters. OR values were derived from the literature, and the

relevant reference citations are cited in the last column. The

probability of recurrence was calculated based on the OR values.

The most influential factor in the patient described herein was the

lack of brain re-expansion (recurrence probability, 96%), followed

by hematoma width (70%) and the presence of senile atrophy (70%).

The first modifiable factor, the type of surgical evacuation,

ranked seventh (54%). Retrospectively, it appears that the

craniocerebral mismatch determined the serial recurrences and, as a

result, the fate of the patient in the present case report. In

theory, MMAE could reduce the risk of recurrence to 13%. However,

the available evidence was derived from studies on primary CSDH

without focusing on high-recurrence-risk patients, as in the case

described herein. The efficacy of MMAE remains to be determined in

this population in future studies.

| Table ISummary table of the characteristics

of the patient in the present study according to the evidence on

hematoma recurrence from the literature. |

Table I

Summary table of the characteristics

of the patient in the present study according to the evidence on

hematoma recurrence from the literature.

| Authors | Parameter | Odds ratio | Probability of

recurrence (%) | Modifiable

factor | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Han et al | Failure of brain

re-expansion | 25.0 | 96 | No | (23) |

| Zhu et al | Hematoma width

(>20 mm) | 2.37 | 70 | No | (12) |

| Han et al | Senile brain

atrophy | 2.36 | 70 | No | (23) |

| Zhu et al | Midline shift (>10

mm) | 1.61 | 62 | No | (12) |

| Zhu et al | Bilateral

location | 1.41 | 59 | No | (12) |

| Zhu et

al | Male gender | 1.32 | 57 | No | (12) |

| Yagnik et

al | Single burr

hole | 1.16 | 54 | Yes | (14) |

| Zhu et

al | Type 1

lesiona | 0.79 | 44 | No | (12) |

| Zhu et

al | Closed drainage

system | 0.45 | 41 | Yes | (12) |

| Shrestha et

al | Steroids | 0.39 | 28 | Yes | (26) |

| Zhu et

al | Irrigation | 0.35 | 26 | Yes | (12) |

| Ironside et

al, Jumah et al | No MMAE | 6.66 | 87 | Yes | (18,19) |

In conclusion, contrary to the common belief, the

management of a CSDH is a complex and challenging task.

Furthermore, despite advances in the primary treatment of CSDH, the

outcomes remain suboptimal in certain cases. Therefore, the

literature has extensively explored potential predictors of

treatment failure. Recurrent CSDH, characterized by multiple

compartments and thick neomembranes, poses even greater challenges.

In fact, effective treatment alternatives for such cases are

extremely limited, as highlighted herein, including the patient in

the present study. Consequently, a more individualized approach is

required, which may involve more aggressive treatment options such

as craniectomy and membranectomy. In addition, future research is

required with the use of more advanced approaches, such as

endovascular embolization of the meningeal artery, which may reduce

the recurrence rate and lead to improved outcomes in patients with

CSDH.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

AGB and GF conceptualized the study. AGB, VEG, GF,

II, AK, TS and KNF made a substantial contribution to the

interpretation and analysis of the patient's data, and wrote and

prepared the draft of the manuscript. GF and AGB treated the

patient and performed the surgical procedures. GF and KNF analyzed

the data and provided critical revisions. GF and AGB confirm the

authenticity of all the data. All authors contributed to manuscript

revision, and have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed was obtained from the patient for

his participation in the present case report. The patient had

provided written informed consent for publication after the second

intervention.

Patient consent for publication

Written informed was obtained from the patient for

the publication of the present case report and any related images.

The patient had provided written informed consent for publication

after the second intervention.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Chang CL, Sim JL, Delgardo MW, Ruan DT and

Connolly ES Jr: Predicting chronic subdural hematoma resolution and

time to resolution following surgical evacuation. Front Neurol.

11(677)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Nouri A, Gondar R, Schaller K and Meling

T: Chronic subdural hematoma (cSDH): A review of the current state

of the art. Brain Spine. 1(100300)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Tommiska P, Lönnrot K, Raj R, Luostarinen

T and Kivisaari R: Transition of a clinical practice to use of

subdural drains after burr hole evacuation of chronic subdural

hematoma: The Helsinki experience. World Neurosurg. 129:e614–e626.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Cofano F, Pesce A, Vercelli G, Mammi M,

Massara A, Minardi M, Palmieri M, D'Andrea G, Fronda C, Lanotte MM,

et al: Risk of recurrence of chronic subdural hematomas after

surgery: A multicenter observational cohort study. Front Neurol.

11(560269)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Hamou H, Alzaiyani M, Pjontek R, Kremer B,

Albanna W, Ridwan H, Clusmann H, Hoellig A and Veldeman M: Risk

factors of recurrence in chronic subdural hematoma and a proposed

extended classification of internal architecture as a predictor of

recurrence. Neurosurg Rev. 45:2777–2786. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Shen J, Yuan L, Ge R, Wang Q, Zhou W,

Jiang XC and Shao X: Clinical and radiological factors predicting

recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma: A retrospective cohort

study. Injury. 50:1634–1640. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Greuter L, Lutz K, Fandino J, Mariani L,

Guzman R and Soleman J: Drain type after burr-hole drainage of

chronic subdural hematoma in geriatric patients: A subanalysis of

the cSDH-Drain randomized controlled trial. Neurosurg Focus.

49(E6)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Pahatouridis D, Alexiou GA, Fotakopoulos

G, Mihos E, Zigouris A, Drosos D and Voulgaris S: Chronic subdural

haematomas: A comparative study of an enlarged single burr hole

versus double burr hole drainage. Neurosurg Rev. 36:151–154.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Fountas K, Kotlia P, Panagiotopoulos V and

Fotakopoulos G: The outcome after surgical vs nonsurgical treatment

of chronic subdural hematoma with dexamethasone. Interdisciplinary

Neurosurgery. 16:70–74. 2019.

|

|

10

|

Bartek J Jr, Sjåvik K, Schaible S, Gulati

S, Solheim O, Förander P and Jakola AS: The role of

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with chronic

subdural hematoma: A Scandinavian population-based multicenter

study. World Neurosurg. 113:e555–e560. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhang JJY, Aw NMY, Tan CH, Lee KS, Chen

VHE, Wang S, Dinesh N, Foo ASC, Yang M, Goh CP, et al: Impact of

time to resumption of antithrombotic therapy on outcomes after

surgical evacuation of chronic subdural hematoma: A multicenter

cohort study. J Clin Neurosci. 89:389–396. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhu F, Wang H, Li W, Han S, Yuan J, Zhang

C, Li Z, Fan G, Liu X, Nie M and Bie L: Factors correlated with the

postoperative recurrence of chronic subdural hematoma: An umbrella

study of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. EClinicalMedicine.

43(101234)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Henry J, Amoo M, Kissner M, Deane T,

Zilani G, Crockett MT and Javadpour M: Management of chronic

subdural hematoma: A systematic review and component network

meta-analysis of 455 studies with 103 645 cases. Neurosurgery.

91:842–855. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Yagnik KJ, Goyal A and Van Gompel JJ:

Twist drill craniostomy vs burr hole drainage of chronic subdural

hematoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir

(Wien). 163:3229–3241. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Miah IP, Holl DC, Blaauw J, Lingsma HF,

den Hertog HM, Jacobs B, Kruyt ND, van der Naalt J, Polinder S,

Groen RJM, et al: Dexamethasone versus surgery for chronic subdural

hematoma. N Engl J Med. 388:2230–2240. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Monteiro A, Housley SB, Kuo CC, Donnelly

BM, Khawar WI, Khan A, Waqas M, Cappuzzo JM, Snyder KV, Siddiqui

AH, et al: The effect of statins on the recurrence of chronic

subdural hematomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World

Neurosurg. 166:244–250. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Yu W, Chen W, Jiang Y, Ma M, Zhang W,

Zhang X and Cheng Y: Effectiveness comparisons of drug therapy on

chronic subdural hematoma recurrence: A Bayesian network

meta-analysis and systematic review. Front Pharmacol.

13(845386)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ironside N, Nguyen C, Do Q, Ugiliweneza B,

Chen CJ, Sieg EP, James RF and Ding D: Middle meningeal artery

embolization for chronic subdural hematoma: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 13:951–957. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jumah F, Osama M, Islim AI, Jumah A, Patra

DP, Kosty J, Narayan V, Nanda A, Gupta G and Dossani RH: Efficacy

and safety of middle meningeal artery embolization in the

management of refractory or chronic subdural hematomas: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Neurochir (Wien).

162:499–507. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ichimura S, Takahara K, Nakaya M, Yoshida

K and Fujii K: Neuroendoscopic Technique for recurrent chronic

subdural hematoma with small craniotomy. Turk Neurosurg.

30:701–706. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wu L, Guo X, Ou Y, Yu X, Zhu B, Yang C and

Liu W: Efficacy analysis of neuroendoscopy-assisted burr-hole

evacuation for chronic subdural hematoma: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Neurosurg Rev. 46(98)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hacıyakupoğlu E, Yılmaz DM, Kınalı B,

Arpacı T, Akbaş T and Hacıyakupoğlu S: Recurrent chronic subdural

hematoma: Report of 13 cases. Open Med (Wars). 13:520–527.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Han S, Feng Y, Xu C, Li X, Zhu F, Li Z,

Zhang C and Bie L: Brain re-expansion predict the recurrence of

unilateral CSDH: A clinical grading system. Front Neurol.

13(908151)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Miki K, Abe H, Morishita T, Hayashi S,

Yagi K, Arima H and Inoue T: Double-crescent sign as a predictor of

chronic subdural hematoma recurrence following burr-hole surgery. J

Neurosurg. 131:1905–1911. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang J: Chinese Society of Neurosurgery,

Chinese Medical Association, Chinese Neurosurgical Critical Care

Specialist Council, Collaborational Group of Chinese Neurosurgical

Translational and Evidence-based Medicine. Expert consensus on drug

treatment of chronic subdural hematoma. Chin Neurosurg J.

7(47)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Shrestha DB, Budhathoki P, Sedhai YR, Jain

S, Karki P, Jha P, Mainali G and Ghimire P: Steroid in chronic

subdural hematoma: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis

post DEX-CSDH trial. World Neurosurg. 158:84–99. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhao Y, Xiao Q, Tang W, Wang R and Luo M:

Efficacy and safety of glucocorticoids versus placebo as an

adjuvant treatment to surgery in chronic subdural hematoma: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled

clinical trials. World Neurosurg. 159:198–206. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Hellwig D, Heinze S, Riegel T and Benes L:

Neuroendoscopic treatment of loculated chronic subdural hematoma.

Neurosurg Clin N Am. 11:525–534. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Krueger EM, Gustin AJ, Gustin PJ, Jaffa Z

and Farhat H: Intraparenchymal hemorrhage after evacuation of

chronic subdural hematoma: A case series and literature review.

World Neurosurg. 155:160–170. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|