Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic had severe repercussions on

global health; currently, this infection is known for its ability

to harm any organ or system in the body (1). As with other viruses (2), the symptoms it causes can become

chronic (3). Indeed, due to the

success of vaccination efforts, it is estimated that 70% of

COVID-19 infections will have a greater long-term impact than

during the acute phase of the infection (4). The persistence of symptoms following a

COVID-19 infection is known as post-COVID-19 syndrome (5). This condition is characterized by the

presence of symptoms for at least 2 months following the initial

infection (6,7). The emergence of this syndrome does not

depend on the duration of the primary infection (8), but rather on factors, such as age and

the number of symptoms during the acute infection (9). The overall prevalence of post-COVID-19

syndrome has been calculated at 41.79%, although significant

variations exist across different populations (10). Due to the ability of the virus to

cross mucosal barriers (11),

post-COVID-19 syndrome can manifest in the cells and structures of

the skin (12). Potential lesions

associated with COVID-19 have been classified into six groups,

listed in order of prevalence: Acral (51%), vesicular (15%),

urticarial (9%), morbilliform (9%), petechial (3%), livedo

reticularis (1%) and other types (15%) (13). The mechanisms related to these

lesions include the excessive production of inflammatory cytokines

and stress hormones with subsequent damage to the production of

proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix (14), as well as dysregulations in the

humoral response of CD8+ T-lymphocytes (15) and residual effects of post-traumatic

stress (16). However, the

dermatological lesions observed in post-COVID-19 syndrome may

differ from those observed during the acute phase of infection.

Given that there is no specific treatment for dermatological

lesions caused by post-COVID-19 syndrome, the treatment of choice

depends on the symptomatology, thus rendering it essential to

describe the type and nature of the lesions presented (17). For this reason, in the present study,

a systematic review of the dermatological lesions and symptoms

presented during post-COVID-19 syndrome was conducted to detail the

clinical spectrum of this condition and guide the therapeutic needs

of those affected.

Data and methods

Using the PICO strategy, a systematic search was

conducted in the repositories of PubMed, Embase, Scopus and Google

Scholar, utilizing the following key words: ‘Long-Covid Syndrome

and skin manifestations’ OR ‘POST-COVID syndrome and cutaneous

manifestations’ OR ‘Post COVID and Skin’. Only original

multicentric articles, such as prospective cohort studies,

retrospective cohort studies, case series and case reports

published between January, 2020 and January, 2024, written in

English or Spanish, involving patients diagnosed with post-COVID-19

syndrome and documenting clinical skin manifestations or cutaneous

appendages, were included. Studies, such as systematic reviews,

meta-analyses, expert consensus, pre-experimental studies and in

vitro studies were excluded, as well as studies with

unavailable content or imprecise information about symptoms and

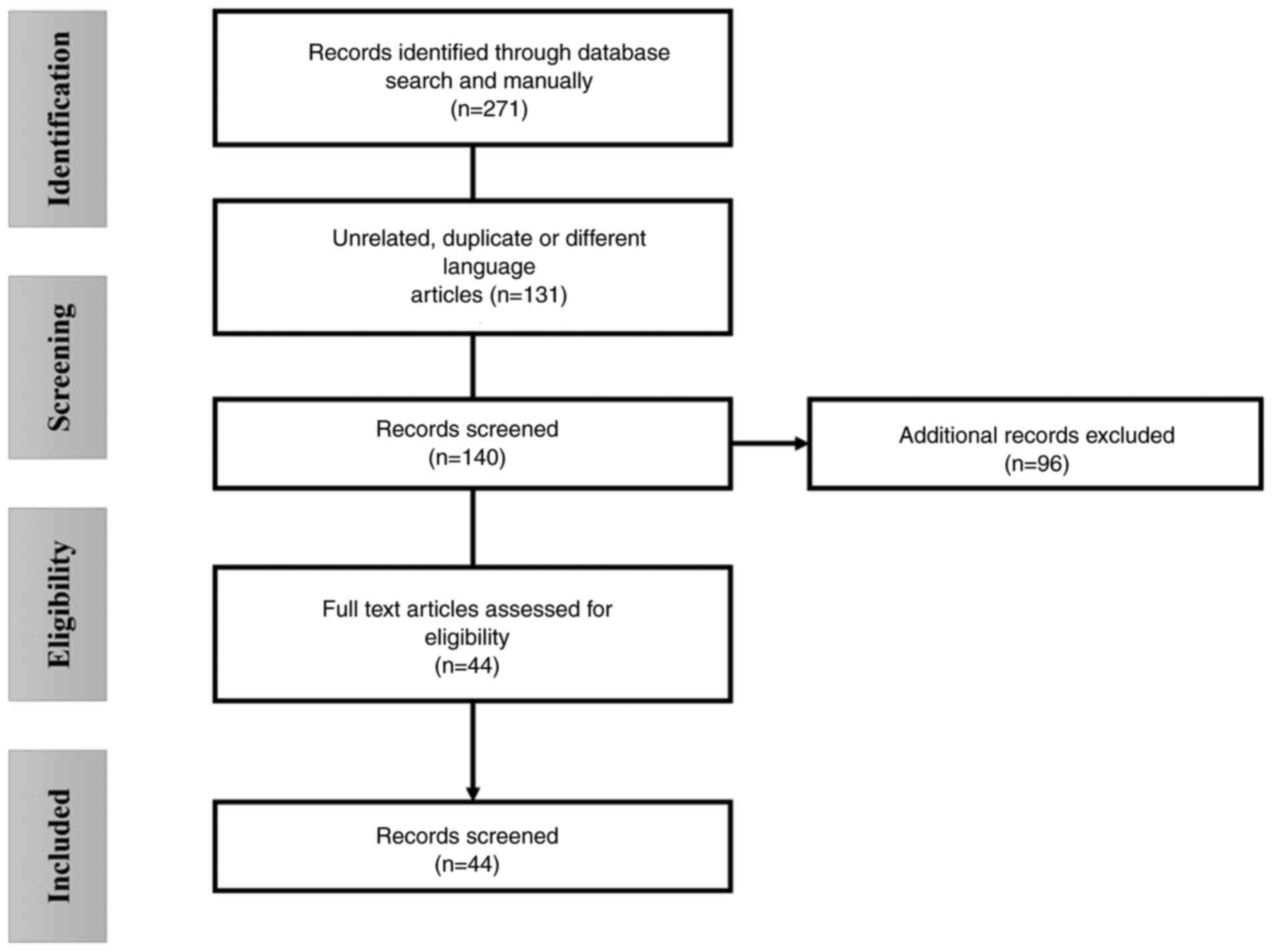

follow-up. Initially, a total of 271 candidate articles were found,

which were reviewed in parallel by two reviewers through the

reading of their abstracts and titles. Following the consensus of

the reviewers, the results of this analysis were organized in a

database, summarizing the characteristics of each record. A total

of 119 studies were discarded due to unrelated information to the

interests of the present systematic review, another 96 for

belonging to other types of studies, one article was excluded for

being in a language other than Spanish or English, and 12 studies

were excluded for duplications, resulting in 44 eligible articles

(Fig. 1).

In the 44 selected articles, data corresponding to

the research question were collected, along with information

regarding the number of participants, presented dermatological

symptoms and follow-up period, among other relevant findings. Of

the included articles, a total of 21 studies were prospective

cohort studies, while four studies were retrospective cohort

studies. Of note, one study was ambispective, and another was a

case-control type study. Additionally, nine studies were

cross-sectional, one study was a case series, and seven studies

were case reports. A list of the included studies is presented in

Table I.

| Table ISummary of the included studies. |

Table I

Summary of the included studies.

| Authors | Type of study | No. of

patients | Features | Findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Menges et

al | P | 442 | 7-Month

follow-up | Non-specific

dermatological symptoms in 11% of patients | (18) |

| Peghin et

al | A | 231 | Healthy

population | 10% Non-specific

symptoms | (19) |

| Peter et

al | R | 11,710 | 12-Month

follow-up | 5.6% of patients

had non-specific rash reactions | (20) |

| Popa et

al | R | 80 | Healthy

population | Non-specific

dermatological symptoms | (21) |

| Munblit et

al | P | 2,649 | More severe effects

in women | 8% of the

population with nonspecific symptoms | (22) |

| Subramanian et

al | P | 48,6149 | Healthy

population | Unspecified

alterations in nails, hair and skin | (23) |

| Fischer et

al | P | 491 | 12 Months

follow-up | Non-specific

symptoms in 23%, worsening depending on the severity of the initial

condition | (24) |

| Leth et

al | P | 49 | Hospitalized

patients | Non-specific skin

manifestations | (25) |

| Ariza et

al | CS | 319 | Psychiatrics

comorbid | Unidentified skin

symptoms | (26) |

| Moreno-Pérez et

al | P | 277 | 14 Weeks

follow-up | 8.36% of patients

with non-specific skin manifestations | (27) |

| Dryden et

al | P | 2,410 | Healthy

population | Skin rash 3.9% per

month and 1.9% after 3 months | (28) |

| Šipetić et

al | CS | 51 | Women with more

severe manifestations | Alterations in

nails, skin and hair: 27.4% of patients in general | (29) |

| Raj et

al | CS | 691 | 9-Month

follow-up | Non-specific skin

symptoms in 1.2% of patients | (30) |

| Funk et

al | P | 8,642 | Pediatric

population | Skin rash 12.50%,

10.30% in non-hospitalized patients | (31) |

| Asakura et

al | CCS | 8,018 | Japanese

population | 1.5% alopecia,

rash, cutaneous chilblains | (32) |

| Alkeraye et

al | CS | 806 | Mostly women | 52.7% with

alopecia, persistence after 3 months | (33) |

|

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas et al | P | 1,969 | Healthy

population | Hair loss (23.9%)

and rash (12%), more affected in women | (34) |

| Jung et

al | R | 1,122 | 4-Month

follow-up | 8.9% skin rash,

9.4% with noticeable hair loss | (35) |

| Kayaaslan et

al | P | 1,092 | Healthy

population | 1% non-specific

symptoms, and hair loss | (36) |

| Hennig et

al | P | 15 | 45 days of

follow-up | Moderate and severe

alopecia in the entire population | (37) |

| Förster et

al | P | 1,459 | Several months of

follow-up | Skin lesions in

2.3%, alopecia in 9.2% of patients | (38) |

| Domènech-Montoliu

et al | P | 484 | More severe in

females and COVID-19 severe infection | Skin lesions in

5.1%, loss of hair density in 22.25% of subjects | (39) |

| Al-Aly et

al | P | 73,453 | Healthy

population | Hair loss and skin

lesions in 7% of subjects | (40) |

| Peter et

al | CS | 12,503 | 12 Months of

follow-up | Skin rash, hair

loss in 7% of subjects | (41) |

| Saberian et

al | CS | 7,226 | Iranian

population | 32% with hair loss,

8% with skin lesions | (42) |

| Rossi et

al | CSR | 14 | 3 Months of

follow-up | Hair loss, worse

results are associated depending on the intensity of COVID | (43) |

| Dumont et

al | P | 1,034 | 12 Weeks

follow-up | Skin lesions and

pruritus in the population | (44) |

| McMahon et

al | P | 330 | 20 to 70 days

follow-up | Presence of

erythematous papules | (45) |

| Weinstock et

al | CS | 136 | Several months of

follow-up | Development of skin

lesions, nodules and alopecia | (46) |

| Bouwensch et

al | P | 160 | Healthy

population | Pruritus in 25%,

blisters and nodules in 12%, Rash, edema in 9%, vesicles and

pigmentary alterations in 6% of patients | (47) |

| Morris et

al | CR | 1 | 1-Month

follow-up | Ecchymosis and

vasculitis | (48) |

| De Medeiros et

al | CR | 1 | Immunocompetent

patient | Case of pemphigus

vulgaris with autoimmune component | (49) |

| Bekaryssova et

al | CS | 193 | Healthy

population | 9.4% of the

population with dermatitis | (50) |

| Qureshi and

Bansal | CR | 1 | Patient with

previous autoimmunity disease | Reactivation of

psoriasis after COVID-19, associated hyperthyroidism | (51) |

| Shimizu et

al | CR | 1 | Healthy

patient | Case of

dermatomyositis and nonspecific rash | (52) |

| Gold et

al | P | 185 | Healthy

population | 7 subjects with

skin rash and cases of Epstein Barr virus reactivation | (53) |

| Gupta et

al | CR | 1 | Healthy

patient | Report of

mucormycosis | (54) |

| Saad and

Mobarak | CR | 1 | Immunocompetent

patient | Cutaneous

mucormycosis secondary to COVID-19 | (55) |

| Ahsan and Rani | CR | 1 | Healthy

patient | Skin rash,

anti-COVID antibodies detected | (56) |

| Richter et

al | P | 59 | 12-Month

follow-up | Anti-epidermis

antibodies were found (41%) | (57) |

|

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas et al | P | 614 | Different

population cohorts | Skin rash according

to variant: Wuhan 12.9%, Alpha 5.7%, Delta 5.0% | (58) |

| Kim et

al | P | 454 | 12-Month

follow-up | ‘COVID toes’ in

1.7% of the population | (59) |

Results

Taken together, the analyzed studies compiled

findings from 626,128 patients screened for dermatological symptoms

secondary to post-COVID-19 syndrome. In the majority of the

records, the findings occurred in a population that was previously

healthy. In five studies, the target population was notable for the

presence of chronical pathologies, psychiatric comorbidities, or a

history of autoimmunity. Furthermore, one study focused on

describing dermatological symptoms due to post-COVID-19 syndrome in

the pediatric population. The average follow-up period and the

onset of symptoms within the analyzed were ~7 months, with a

minimum follow-up of 6 weeks following the diagnosis of COVID-19

and up to a maximum of 12 months post-diagnosis. The most prevalent

dermatological symptoms in the population are detailed in specific

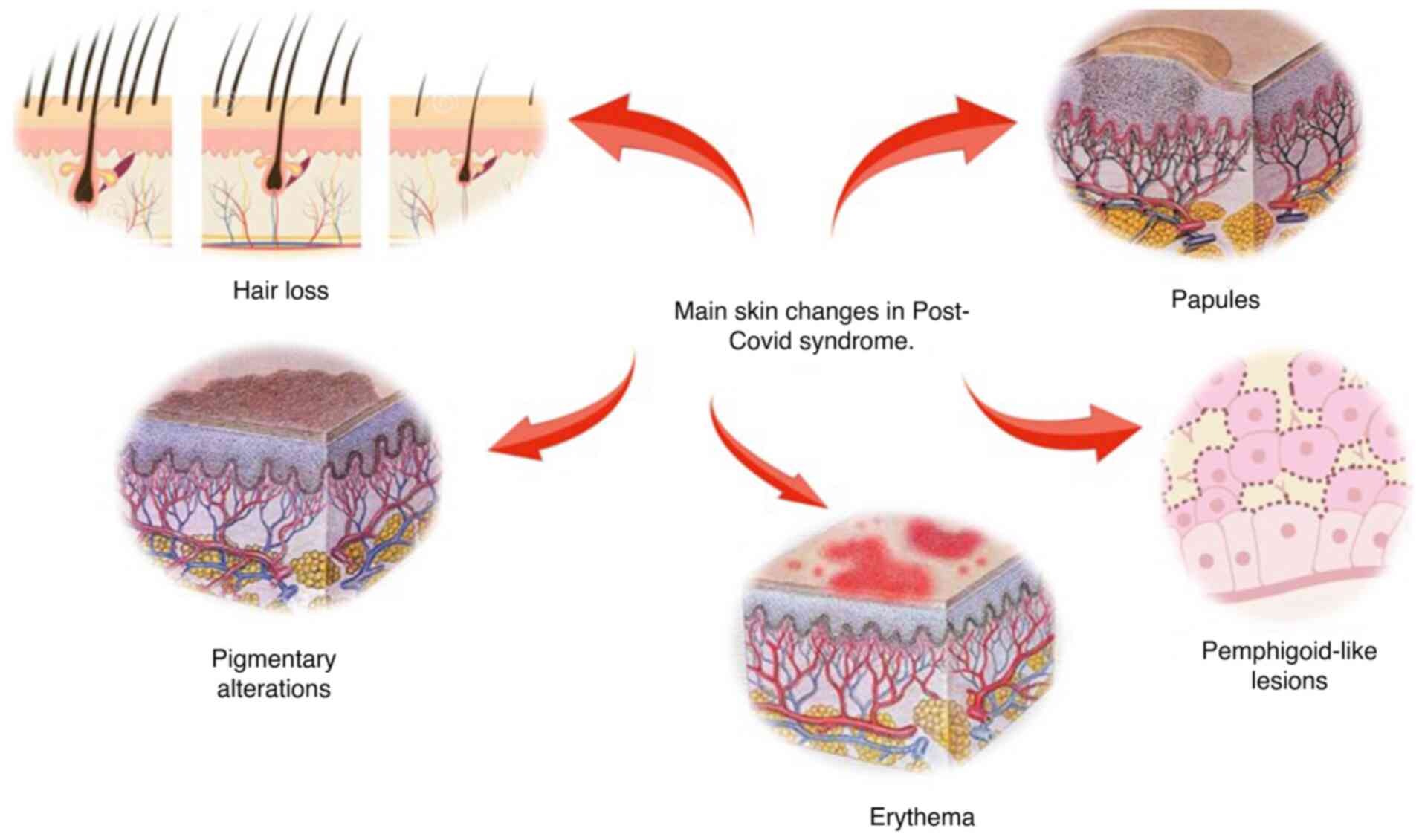

sections below. Additionally, Fig. 2

provides a graphical representation of examples of these

conditions.

Non-specific dermatological

manifestations

Among the studies analyzed, 14 articles described

non-specific cutaneous symptoms as the main finding. These symptoms

were described as ‘skin rash’, ‘dermatological alterations’ and

‘cutaneous symptoms’, without specifying the nature or

characteristics of these alterations (18-31).

The prevalence of this condition varied among the articles, with

the majority of studies indicating a percentage ranging from 5 to

11% of the population. Of note, one study reported a minimum of

1.2% (30), and another reported a

maximum prevalence of 27.4% (29) in

the population. Additionally, three studies highlighted the female

sex and hospitalization as risk factors for presenting these

symptoms with greater severity (22,29,31).

Symptoms associated with hair

health

In addition to the non-specific cutaneous symptoms,

a total of 13 studies described a certain degree of affliction in

hair health. These conditions ranged from a decrease in hair

density and thinning of the follicle to pronounced persistent

alopecia lasting for months, with these issues enduring for an

average period of 3 months following acute COVID-19 infection. The

prevalence of this hair loss demonstrated a high variability,

manifesting in as few as 2% of the population (32) to >50% of study subjects (33), with the majority of the studies

indicating a prevalence between 7 to 35% (34-43).

In two studies, the severity of alopecia was linked to both the

female sex (32) and to the severity

of the initial COVID-19 infection (43).

Skin lesions

On the other hand, six studies described

well-defined skin lesions with distinct characteristics. In two

studies, the presence of papular lesions with irregular borders and

erythematous features was described (44,45). In

two other studies, the presence of subcutaneous nodules was

documented (46,47), one of which also reported the

occurrence of pruritus in 25% of the population, as well as the

formation of blisters and subcutaneous nodules in 12% of subjects,

edema in 9%, pigmentary changes and vesicle formation in 6%

(47). Additionally, one study

mentioned ecchymosis associated with vasculitis (48), and another described pemphigus

vulgaris-like lesions (49).

Dermatitis/associated pathologies

In six studies, cases of dermatitis and pathologies

that appeared concomitantly in the subjects analyzed were

presented. In one study, ~9.4% of the population exhibited

dermatitis with a significant inflammatory component (50). Additionally, two studies mentioned

the worsening of pre-existing pathologies related to autoimmunity,

such as the clinical reactivation of psoriasis (51) and dermatomyositis (52), as well as the reactivation of the

Epstein-Barr virus with the development of characteristic herpetic

lesions (53). Furthermore, two

cases of mucormycosis in immunocompetent patients were reported

(54,55).

Additional dermatological

findings

A total of four studies focused on uncommon

alterations. In two studies, antibodies against the epidermis were

found in up to 41% of the affected subjects (56,57). On

the other hand, one study analyzed the prevalence of cutaneous

symptoms based on the viral variant detected during the primary

infection, with a prevalence of 12.9% for the Wuhan variant, 5.7%

for the Alpha variant and 5% for the Delta type (58). Finally, one study reported the

presence of ‘COVID toes’, a finding where the skin of one or more

toes exhibits edema and bright erythema that gradually turns

violet, potentially showing violaceous brown spots, in 1.7% of its

population (59).

Possible pathophysiological mechanisms

involved in dermatological symptoms in post-COVID-19 infection

Some of the studies reviewed described potential

pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the onset of

dermatological symptoms during the post-COVID-19 state. First, the

cytotoxic potential of the coronavirus was suggested as a possible

contributing factor through molecular interactions with

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors present on the

host cell surface, which are abundantly expressed in the skin

(60). The interaction between

SARS-CoV-2 and this receptor induces endothelial dysfunction

characterized by localized hyperinflammation, vasculitis,

deposition of complement proteins, and the subsequent development

of skin and appendage lesions (61).

Furthermore, the persistence of this inflammatory

state would increase the production of specific interleukins (IL),

such as IL-6 and IL-4. The former has been linked to the loss of

immune regulation that normally maintains hair follicles in an

immune-privileged state, thereby ensuring their normal growth

(62). Elevated levels of IL-4, on

the other hand, promote keratinocyte apoptosis (63). These alterations, combined with the

overexpression of matrix metalloproteinases 1 and 3, may represent

the underlying mechanism responsible for symptoms, such as hair

loss. This is due to the fact that they can modify the cellular

microenvironment at the base of the hair bulb, thereby promoting

the initiation of the catagen phase in the hair growth cycle

(43).

Additionally, the studies included in the present

systematic review describe mechanisms related to alterations in the

hypothalamic-pituitary axis, generation of anti-epidermal

antibodies and mitochondrial dysfunction in epidermal cells. These

mechanisms have been previously identified as contributors to

long-term dermatological symptoms, not only in COVID-19, but also

in other viral infections, suggesting they may represent a common

pathogenic pathway (64,65).

Clinical implications of the findings

for dermatological practice

According to the analyzed studies, dermatological

symptoms following COVID-19 infection constitute one of the five

major symptom clusters observed in recovered patients. Notably,

these symptoms tend to appear at a later stage (22). The average prevalence of

dermatological symptoms in affected individuals is 51.07%,

primarily concerning hair-related conditions, which have been

proven to be among the most challenging to treat due to their poor

response to treatment (with a resolution rate <50%).

Additionally, they are associated with a more prominent negative

effect on the quality of life of patients and emotional well-being

(19,29,36,37).

Moreover, the onset of these symptoms appears to

follow a variable pattern, with manifestation occurring as early as

3 months post-acute phase, up to a maximum of 18 months in studies

with longer follow-up periods. Notably, there is a possibility that

these dermatological lesions may become chronic, as suggested by a

study theorizing that dermatological manifestations following

COVID-19 may persist indefinitely if left untreated (32) or may reappear periodically with

increased severity (47).

The preceding statements hold significant

implications for dermatological clinical practice. Given that skin

lesions secondary to the post-COVID-19 condition tend to manifest

at a later stage, establishing a link between a prior COVID-19

infection and these conditions can be particularly challenging.

Furthermore, studies indicate a poor therapeutic response to these

lesions, particularly in cases of hair loss, which is often

perceived as a relatively minor issue by numerous healthcare

professionals. However, this complication has emerged as having the

greatest impact on the overall well-being of individuals, rendering

their management a priority in dermatological care.

Discussion

The present systematic review detailed the findings

from studies focusing on post-COVID-19 syndrome and the

dermatological conditions it causes. The literature review

indicated a relatively limited number of records of dermatological

alterations resulting from this syndrome. This scarcity may be due

to the fact that such dermatological manifestations are not as

apparent until the initial impact of the health emergency is

mitigated (66). On the one hand,

while the majority of studies reported only mild and non-specific

skin lesions, other studies revealed two main findings: Firstly, an

increase in cutaneous symptoms associated with hyperinflammation

and immune dysregulations, and secondly, a significant prevalence

of hair loss and alopecia in the affected population.

As regards the first finding, the included studies

reported multiple cases of subjects whose pathology was associated

with hyperinflammation and the development of autoimmunity,

including the reactivation of autoimmune and viral diseases in a

silent state, as well as infections by opportunistic pathogens in

previously healthy individuals. Post-COVID-19 syndrome is

characterized by the development of residual inflammation due to

direct viral toxicity, as well as alterations in the regulatory

function of T-lymphocytes (67).

Studies focusing on this aspect have determined that after

recovering from the acute phase of COVID-19, the virus can cause

T-lymphocytes to exhibit autologous epitopes on their antigen

identification cell receptors, thus creating an autoimmune

environment, particularly in the female body (68).

Moreover, the excessive secretion of IL-6, D-dimer

and lymphopenia produced during the primary COVID-19 infection

increases the likelihood of developing post-COVID-19 syndrome

(69). This is consistent with the

findings that have been reported in previous research (70) and in the present systematic review,

where females and subjects with severe COVID-19 infection presented

more intense dermatological symptoms compared to the remainder of

the population. In line with this finding, previous research has

confirmed that some patients develop autoantibodies following

COVID-19 infection, regardless of whether they have a history of

autoimmunity or not (71). A

proposed mechanism indicates the viral capacity to generate

molecular mimicry with normal body structures (71). Thus, it is possible that the

generation of antibodies against skin layers contributes to the

development of skin lesions as indicated by some studies analyzed

in this review (56,57).

As regards hair loss and alopecia, these conditions

were initially reported during the peak of the pandemic in Spain

(72), and described as expected

findings during the acute phase and convalescence of patients

infected with COVID-19(73). At that

time, these conditions were considered mild and reversible, as with

other viral and bacterial infections, resulting from the alteration

of hair growth cycles following exposure to persistent inflammation

affecting the metabolism of keratinocytes and the dermal papilla

(74).

However, in the case of post-COVID-19 syndrome, it

has been reported that the onset of alopecia occurs more rapidly

and lasts longer compared to other pathogens, suggesting direct

damage to the hair follicle. This is due to the fact that ACE2

receptors, used by COVID-19 for viral entry, are present in both

mesenchymal cells of the hair follicle and its basal layers

(75). Additionally, it has been

theorized that certain components of the hair follicle increase

immunological reactivity against COVID-19, consequently leading to

an increase in antigen-antibody interactions in this area,

resulting in the degradation of the follicle root structures

(76). Furthermore, it is considered

that this localized toxicity generates intense oxidative stress,

leading to the premature onset of the catagen phase of the hair

follicle and hair apoptosis, as well as a reduction in

anticoagulant proteins in the perifollicular vessels, which in turn

facilitates the formation of microthrombi that reduce blood flow to

the hair root, causing it to thin and become fragile (77).

Although hair loss is considered a benign symptom

without real systemic repercussions, its impact on body aesthetics

is crucial for the individual, particularly considering that,

compared with other dermatopathies, the availability of treatments

for this condition is limited (78).

This renders hair loss one of the most critical dermatological

effects of post-COVID-19 syndrome, given the high prevalence rate

of this condition. Thus, the timely approach to this condition in

subjects with risk factors, such as women and severe COVID-19

should be considered a priority in dermatological health

matters.

Although the findings from the present systematic

review are notable due to their clinical implications in

dermatological practice, it is important to highlight the inherent

limitations of the present study. Since the studies analyzed

predominantly rely on reports provided by affected patients, there

is a notable risk of human bias. The integration of technological

tools, such as neural networks for the analysis of dermatological

lesions in post-COVID-19 syndrome, may allow for more accurate data

on the impact of this condition on dermatological health, as has

been observed with other conditions (79,80).

Therefore, the associations generated through these analytical

tools could contribute to future studies identifying both the risk

factors for symptom onset and the pathogenic pathways responsible

for the lesions in post-COVID-19 syndrome.

In conclusion, the present systematic review found

that the dermatological manifestations of post-COVID-19 syndrome

are primarily hair loss and skin lesions associated with persistent

inflammation and the development of autoimmunity, with the severity

of the initial clinical presentation and female sex being risk

factors for severity. Additionally, given that dermatological

lesions in post-COVID-19 syndrome may present in a delayed manner,

their diagnosis should always be considered in patients

experiencing symptoms that cannot be explained by other

dermatological conditions. Furthermore, due to the limited

therapeutic success for some symptoms, such as hair loss, further

studies are required to focus on comparing specific therapeutic

interventions for these conditions.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

BACF was a main contributor to the conception of the

study, as well as to the literature search for related studies.

BACF, WMR and DTJ were involved in the literature review, in the

writing of the manuscript, and in the analysis and interpretation

of the patient data obtained from the studies. BACF and DTJ confirm

the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Garg S, Garg M, Prabhakar N, Malhotra P

and Agarwal R: Unraveling the mystery of Covid-19 cytokine storm:

From skin to organ systems. Dermatol Ther.

33(e13859)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Carod-Artal FJ and García-Moncó JC:

Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and classification of the

neurological symptoms of post-COVID-19 syndrome. Neurol Perspect.

1:S5–S15. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Rocha KO, Zanuncio VV, de Freitas BAC and

Lima LM: ‘COVID toes’: A meta-analysis of case and observational

studies on clinical, histopathological, and laboratory findings.

Pediatr Dermatol. 38:1143–1149. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Goetzl EJ and Kapogiannis D: Long-COVID:

Phase 2 of the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Med. 135:1277–1279.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sykes DL, Holdsworth L, Jawad N,

Gunasekera P, Morice AH and Crooks MG: Post-COVID-19 symptom

burden: What is long-COVID and how should we manage It? Lung.

199:113–119. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Castanares-Zapatero D, Chalon P, Kohn L,

Dauvrin M, Detollenaere J, Maertens de Noordhout C, Primus-de Jong

C, Cleemput I and Van den Heede K: Pathophysiology and mechanism of

long COVID: A comprehensive review. Ann Med. 54:1473–1487.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Raveendran AV, Jayadevan R and Sashidharan

S: Long COVID: An overview. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 15:869–875.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Palacios-Ceña D,

Gómez-Mayordomo V, Florencio LL, Cuadrado ML, Plaza-Manzano G and

Navarro-Santana M: Prevalence of post-COVID-19 symptoms in

hospitalized and non-hospitalized COVID-19 survivors: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 92:55–70.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lippi G, Sanchis-Gomar F and Henry BM:

COVID-19 and its long-term sequelae: What do we know in 2023? Pol

Arch Intern Med. 133(16402)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sk Abd Razak R, Ismail A, Abdul Aziz AF,

Suddin LS, Azzeri A and Sha'ari NI: Post-COVID syndrome prevalence:

A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health.

24(1785)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kabeerdass N, Thangaswamy S,

Mohanasrinivasan V, Rajasekaran C, Sundaram S, Nooruddin T and

Mathanmohun M: Green synthesis-mediated nanoparticles and their

curative character against post COVID-19 skin diseases. Curr

Pharmacol Rep. 8:409–417. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Yuen S: Dermatology services: The new

normal post COVID-19. Skin Health Dis. 1(e30)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

de Masson A, Bouaziz JD, Sulimovic L,

Cassius C, Jachiet M, Ionescu MA, Rybojad M, Bagot M and Duong TA:

SNDV (French National Union of Dermatologists-Venereologists).

Chilblains is a common cutaneous finding during the COVID-19

pandemic: A retrospective nationwide study from France. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 83:667–670. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Aldahish A, Vasudevan R, Salem H,

Alqahtani A, AlQasim S, Alqhatani A, Al Shahrani M, Al Mohsen L,

Hajla M, Calina D and Sharifi-Rad J: Telogen effluvium and

COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci.

27:7823–7830. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Zou H and Daveluy S: Toxic epidermal

necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome after COVID-19 infection

and vaccination. Australas J Dermatol. 64:e1–e10. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Tay MZ, Poh CM, Rénia L, MacAry PA and Ng

LFP: The trinity of COVID-19: Immunity, inflammation and

intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 20:363–374. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A'Court C, Buxton

M and Husain L: Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care.

BMJ. 370(m3026)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Menges D, Ballouz T, Anagnostopoulos A,

Aschmann HE, Domenghino A, Fehr JS and Puhan MA: Burden of

post-COVID-19 syndrome and implications for healthcare service

planning: A population-based cohort study. PLoS One.

16(e0254523)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Peghin M, Palese A, Venturini M, De

Martino M, Gerussi V, Graziano E, Bontempo G, Marrella F, Tommasini

A, Fabris M, et al: Post-COVID-19 symptoms 6 months after acute

infection among hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. Clin

Microbiol Infect. 27:1507–1513. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Peter RS, Nieters A, Kräusslich HG,

Brockmann SO, Göpel S, Kindle G, Merle U, Steinacker JM,

Rothenbacher D and Kern WV: EPILOC Phase 1 Study Group. Post-acute

sequelae of covid-19 six to 12 months after infection: population

based study. BMJ. 379(e071050)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Popa MV, Bogdan Goroftei ER, Gutu C,

Duceac M, Marcu C, Popescu R, Popescu R, Druguș D and Duceac LD:

Observational study of post-COVID-19 syndrome in healthcare workers

infected with sars-COV-2 virus: General and oral cavity

complications. Rom J Oral Rehabil. 15:198–207. 2023.

|

|

22

|

Munblit D, Bobkova P, Spiridonova E,

Shikhaleva A, Gamirova A, Blyuss O, Nekliudov N, Bugaeva P,

Andreeva M, DunnGalvin A, et al: Incidence and risk factors for

persistent symptoms in adults previously hospitalized for COVID-19.

Clin Exp Allergy. 51:1107–1120. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Hughes

S, Myles P, Wiliams T, Gokhale K, Taverner T, Chandan J, Brown K,

Simms-Williams N, et al: Assessment of 115 symptoms for long COVID

(post-COVID-19 condition) and their risk factors in

non-hospitalised individuals: a retrospective matched cohort study

in UK primary care. Res Sq, 2022.

|

|

24

|

Fischer A, Badier N, Zhang L, Elbéji A,

Wilmes P, Oustric P, Benoy C, Ollert M and Fagherazzi G: Long COVID

classification: Findings from a clustering analysis in the

predi-COVID cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health.

19(16018)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Leth S, Gunst JD, Mathiasen V, Hansen K,

Søgaard O, Østergaard L, Jensen-Fangel S, Storgaard M and Agergaard

J: Persistent symptoms in patients recovering from COVID-19 in

Denmark. Open Forum Infect Dis. 8(ofab042)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Ariza M, Cano N, Segura B, Adan A,

Bargalló N, Caldú X, Campabadal A, Jurado MA, Mataró M, Pueyo R, et

al: COVID-19 severity is related to poor executive function in

people with post-COVID conditions. J Neurol. 270:2392–2408.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Moreno-Pérez O, Merino E, Leon-Ramirez JM,

Andres M, Ramos JM, Arenas-Jiménez J, Asensio S, Sanchez R,

Ruiz-Torregrosa P, Galan I, et al: Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome.

Incidence and risk factors: A Mediterranean cohort study. J Infect.

82:378–383. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Dryden M, Mudara C, Vika C, Blumberg L,

Mayet N, Cohen C, Tempia S, Parker A, Nel J, Perumal R, et al:

Post-COVID-19 condition 3 months after hospitalisation with

SARS-CoV-2 in South Africa: A prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob

Health. 10:e1247–e1256. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Šipetić T, Rajković D, Bogavac Stanojević

N, Marinković V, Meštrović A and Rouse MJ: SMART pharmacists

serving the new needs of the post-COVID patients, leaving no-one

behind. Pharmacy (Basel). 11(61)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Raj SVA, Jacob A, Ambu V, Wilson T and

Renuka R: Post COVID-19 clinical manifestations and its risk

factors among patients in a northern district in Kerala, India. J

Family Med Prim Care. 11:5312–5319. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Funk AL, Kuppermann N, Florin TA, Tancredi

DJ, Xie J, Kim K, Finkelstein Y, Neuman MI, Salvadori MI,

Yock-Corrales A, et al: Post-COVID-19 conditions among children 90

days after SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw Open.

5(e2223253)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Asakura T, Kimura T, Kurotori I, Kenichi

K, Hori M, Hosogawa M, Saijo M, Nakanishi K, Iso H and Tamakoshi A:

Case-control study of long COVID, Sapporo, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis.

29:956–966. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Alkeraye S, Alrashidi A, Alotaibi NS,

Almajli N, Alkhalifah B, Bajunaid N, Alharthi R, AlKaff T and

Alharbi K: The association between hair loss and COVID-19: The

impact of hair loss after COVID-19 infection on the quality of life

among residents in Saudi Arabia. Cureus. 14(e30266)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Martín-Guerrero

JD, Pellicer-Valero ÓJ, Navarro-Pardo E, Gómez-Mayordomo V,

Cuadrado ML, Arias-Navalón JA, Cigarán-Méndez M, Hernández-Barrera

V and Arendt-Nielsen L: Female sex is a risk factor associated with

long-term post-COVID related-symptoms but not with COVID-19

symptoms: The LONG-COVID-EXP-CM multicenter study. J Clin Med.

11:413–423. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Jung YH, Ha EH, Choe KW, Lee S, Jo DH and

Lee WJ: Persistent symptoms after acute COVID-19 infection in

omicron era. J Korean Med Sci. 37(e213)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kayaaslan B, Eser F, Kalem AK, Kaya G,

Kaplan B, Kacar D, Hasanoglu I, Coskun B and Guner R: Post-COVID

syndrome: A single-center questionnaire study on 1007 participants

recovered from COVID-19. J Med Virol. 93:6566–6574. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Hennig V, Schuh W, Neubert A, Mielenz D,

Jäck HM and Schneider H: Increased risk of chronic fatigue and hair

loss following COVID-19 in individuals with hypohidrotic ectodermal

dysplasia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 16(373)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Förster C, Colombo MG, Wetzel AJ, Martus P

and Joos S: Persisting symptoms after COVID-19. Dtsch Arztebl Int.

119:167–174. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Domènech-Montoliu S, Puig-Barberà J,

Pac-Sa MR, Vidal-Utrillas P, Latorre-Poveda M, Del Rio-González A,

Ferrando-Rubert S, Ferrer-Abad G, Sánchez-Urbano M, Aparisi-Esteve

L, et al: Complications post-COVID-19 and risk factors among

patients after six months of a SARS-CoV-2 infection: A

population-based prospective cohort study. Epidemiologia (Basel).

3:49–67. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Al-Aly Z, Xie Y and Bowe B:

High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of

COVID-19. Nature. 594:259–264. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Peter RS, Nieters A, Kräusslich HG,

Brockmann SO, Göpel S, Kindle G, Merle U, Steinacker JM,

Rothenbacher D and Kern WV: EPILOC Phase 1 Study Group. Post-acute

sequelae of covid-19 six to 12 months after infection: Population

based study. BMJ. 379(e071050)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Saberian P, Pazooki B, Hasani-Sharamin P,

Garjani K, Ahmadi Hatam Z, Dadashi F and Baratloo A:

Persistent/late-onset complications of COVID-19 in general

population: A cross-sectional study in Tehran, Iran. Int J

Community Based Nurs Midwifery. 10:234–245. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Rossi A, Magri F, Sernicola A, Michelini

S, Caro G, Muscianese M, Di Fraia M, Chello C, Fortuna MC and

Grieco T: Telogen effluvium after SARS-CoV-2 infection: A series of

cases and possible pathogenetic mechanisms. Skin Appendage Disord.

21:1–5. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Dumont R, Richard V, Lorthe E, Loizeau A,

Pennacchio F, Zaballa ME, Baysson H, Nehme M, Perrin A, L'Huillier

AG, et al: A population-based serological study of post-COVID

syndrome prevalence and risk factors in children and adolescents.

Nat Commun. 13(7086)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

McMahon DE, Gallman AE, Hruza GJ,

Rosenbach M, Lipoff JB, Desai SR, French LE, Lim H, Cyster JG, Fox

LP, et al: Long COVID in the skin: A registry analysis of COVID-19

dermatological duration. Lancet Infect Dis. 21:313–314.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Weinstock LB, Brook JB, Walters AS, Goris

A, Afrin LB and Molderings GJ: Mast cell activation symptoms are

prevalent in long-COVID. Int J Infect Dis. 112:217–226.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Bouwensch C, Hahn V and Boulmé F: Analysis

of 160 nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients with mild to moderate

symptoms from an Austrian general medical practice: From typical

disease pattern to unexpected clinical features. Wien Med

Wochenschr. 172:198–210. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Morris D, Patel K, Rahimi O, Sanyurah O,

Iardino A and Khan N: ANCA vasculitis: A manifestation of

post-Covid-19 syndrome. Respir Med Case Rep.

34(101549)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

De Medeiros VLS, Monteiro-Neto AU, França

DDT, Castelo Branco R, de Miranda Coelho ÉO and Takano DM:

Pemphigus vulgaris after COVID-19: A case of induced autoimmunity.

SN Compr Clin Med. 3:1768–1772. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Bekaryssova D, Joshi M, Gupta L,

Yessirkepov M, Gupta P, Zimba O, Gasparyan AY, Ahmed S, Kitas GD

and Agarwal V: Knowledge and perceptions of reactive arthritis

diagnosis and management among healthcare workers during the

COVID-19 pandemic: Online survey. J Korean Med Sci.

37(e355)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Qureshi NK and Bansal SK: Autoimmune

thyroid disease and psoriasis vulgaris after COVID-19 in a male

teenager. Case Rep Pediat. 2021(7584729)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Shimizu H, Matsumoto H, Sasajima T, Suzuki

T, Okubo Y, Fujita Y, Temmoku J, Yoshida S, Asano T, Ohira H, et

al: New-onset dermatomyositis following COVID-19: A case report.

Front Immunol. 13(1002329)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Gold JE, Okyay RA, Licht WE and Hurley DJ:

Investigation of long COVID prevalence and its relationship to

epstein-barr virus reactivation. Pathogens. 10(763)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Gupta A and Singh V: Mucormycosis: ‘The

black fungus’ trampling post-COVID-19 patients. Natl J Maxillofac

Surg. 12:131–132. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Saad RH and Mobarak FA: The diversity and

outcome of post-covid mucormycosis: A case report. Int J Surg Case

Rep. 88(106522)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Ahsan T and Rani B: A case of multisystem

inflammatory syndrome post-COVID-19 infection in an adult. Cureus.

12(e11961)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Richter AG, Shields AM, Karim A, Birch D,

Faustini SE, Steadman L, Ward K, Plant T, Reynolds G, Veenith T, et

al: Establishing the prevalence of common tissue-specific

autoantibodies following severe acute respiratory syndrome

coronavirus 2 infection. Clin Exp Immunol. 205:99–105.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C,

Cancela-Cilleruelo I, Rodríguez-Jiménez J, Gómez-Mayordomo V,

Pellicer-Valero OJ, Martín-Guerrero JD, Hernández-Barrera V,

Arendt-Nielsen L and Torres-Macho J: Associated-onset symptoms and

post-COVID-19 symptoms in hospitalized COVID-19 survivors infected

with wuhan, alpha or delta SARS-CoV-2 variant. Pathogens.

11(725)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Kim Y, Bitna-Ha Kim SW, Chang HH, Kwon KT,

Bae S and Hwang S: Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome in patients after

12 months from COVID-19 infection in Korea. BMC Infect Dis.

22(93)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Cazzato G, Cascardi E, Colagrande A, Foti

C, Stellacci A, Marrone M, Ingravallo G, Arezzo F, Loizzi V,

Solimando AG, et al: SARS-CoV-2 and skin: New insights and

perspectives. Biomolecules. 12(1212)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Gawaz A and Guenova E: Microvascular skin

manifestations caused by COVID-19. Hamostaseologie. 41:387–396.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Pondeljak N and Lugović-Mihić L:

Stress-induced interaction of skin immune cells, hormones, and

neurotransmitters. Clin Ther. 42:757–770. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Mandt N, Geilen CC, Wrobel A, Gelber A,

Kamp H, Orfanos CE and Blume-Peytavi U: Interleukin-4 induces

apoptosis in cultured human follicular keratinocytes, but not in

dermal papilla cells. Eur J Dermatol. 12:432–438. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Genovese G, Moltrasio C, Berti E and

Marzano AV: Skin manifestations associated with COVID-19: Current

knowledge and future perspectives. Dermatology. 237:1–12.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Mui UN, Haley CT, Vangipuram R and Tyring

SK: Human oncoviruses: Mucocutaneous manifestations, pathogenesis,

therapeutics, and prevention: Hepatitis viruses, human T-cell

leukemia viruses, herpesviruses, and Epstein-Barr virus. J Am Acad

Dermatol. 81:23–41. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Deshmukh V, Motwani R, Kumar A, Kumari C

and Raza K: Histopathological observations in COVID-19: A

systematic review. J Clin Pathol. 74:76–83. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Najafi MB and Javanmard SH: Post-COVID-19

syndrome mechanisms, prevention and management. Int J Prev Med.

14(59)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Yong SJ: Long COVID or post-COVID-19

syndrome: Putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments.

Infect Dis (Lond). 53:737–754. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Batiha GE, Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI

and Welson NN: Pathophysiology of post-COVID syndromes: A new

perspective. Virol J. 19(158)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Jimeno-Almazán A, Pallarés JG,

Buendía-Romero Á, Martínez-Cava A, Franco-López F, Sánchez-Alcaraz

Martínez BJ, Bernal-Morel E and Courel-Ibáñez J: Post-COVID-19

syndrome and the potential benefits of exercise. Int J Environ Res

Public Health. 18(5329)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Stoian M, Procopiescu B, Șeitan S and

Scarlat G: Post-COVID-19 syndrome: Insights into a novel

post-infectious systemic disorder. J Med Life. 16:195–202.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Goren A, Vaño-Galván S, Wambier CG, McCoy

J, Gomez-Zubiaur A, Moreno-Arrones OM, Shapiro J, Sinclair RD, Gold

MH, Kovacevic M, et al: A preliminary observation: Male pattern

hair loss among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Spain-A potential

clue to the role of androgens in COVID-19 severity. J Cosmet

Dermatol. 19:1545–1547. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Nguyen B and Tosti A: Alopecia in patients

with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAAD Int.

7:67–77. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Czech T, Sugihara S and Nishimura Y:

Characteristics of hair loss after COVID-19: A systematic scoping

review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 21:3655–3662. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Sattur SS and Sattur IS: COVID-19

infection: Impact on hair. Indian J Plast Surg. 54:521–526.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Wei KC, Huang MS and Tsung-Hsien C: Dengue

VIPHHFDPC. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 8(268)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Gentile P: Hair loss and telogen effluvium

related to COVID-19: The potential implication of adipose-derived

mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma as regenerative

strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 23(9116)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Kinoshita-Ise M, Fukuyama M and Ohyama M:

Recent advances in understanding of the etiopathogenesis,

diagnosis, and management of hair loss diseases. J Clin Med.

12(3259)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Hu R, Mo Q, Xie Y, Xu Y, Chen J, Yang Y,

Zhou H, Tang ZR and Wu WQ: AVMSN: An audio-visual two stream crowd

counting framework under low-quality conditions. IEEE Access.

9(1)2021.

|

|

80

|

Hu R, Tang ZR, Wu EQ, Yang R and Li J:

RDC-SAL: Refine distance compensating with quantum scale-aware

learning for crowd counting and localization. Appl Intell.

52:14336–14348. 2022.

|