Introduction

Biliary tract cancer (BTC), also known as

cholangiocarcinoma, is a cancer of the digestive system that

originates in the biliary tract, which transports bile from the

liver to the digestive tract (1).

BTC is a relatively rare type of cancer worldwide. However, high

incidence rates have been reported in Asia, thus rendering it the

sixth most common cause of cancer-related mortality in Korea

(2).

BTC is also well known for its poor prognosis and

the absence of an effective therapeutic target. Despite the

benefits of targeted therapies observed in the majority of solid

cancers, including lung, breast and even colorectal cancers, since

the 2000s, well-known targeted therapies, such as anti-human

epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) or anti-EGFR agents have

only marginally benefited patients with BTC (3). While the age standardized mortality

rate for lung cancer and colorectal cancer significantly decreased

over the past decade, from 36.6 to 14.9 per 100,000 and from 10.1

to 7.2, respectively, the mortality rate of patients with BTC has

exhibited only a minimal improvement (4.5 to 4.0 per 100,000, from

2010 to 2020) (2,4).

Due to its low incidence rate and poor prognosis,

BTC has been overlooked in major clinical studies. Limited research

and a lack of the accurate understanding of its current

epidemiological characteristics are also key issues with respect to

BTC treatment. With various chemotherapy combinations and the

discovery of therapeutic targets through next-generation

sequencing, along with the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors, the

treatment landscape for biliary cancer is evolving (5). However, there is a paucity of in-depth

studies in this area. Although reports indicate that PD-L1

expression and immune infiltration influence the prognosis of

patients with liver cancer including BTC (6-8),

conclusive results require further validation through prospective

clinical trials and translational studies.

Korea, along with Thailand and Chile, has one of the

highest incidences of BTC worldwide (14.5 per 100,000) (1). These regions exhibit differences in

etiology and genomic landscape, which in turn affect the overall

prognosis of patients with BTC. Therefore, regional exploration is

essential to understand these variations (9,10). The

National Health Information Database (NHID) of the National Health

Insurance Service (NHIS) also contributes to the positioning of

Korea as a valuable cohort for BTC research. The present study

aimed to investigate the recent trends in the prognosis of patients

with BTC and explores the differences based on patient

comorbidities and tumor anatomic sites.

Patients and methods

Data source

The data used in the present study were obtained

from the NHIS of Korea. Korean citizens are obligated to enroll in

the NHIS for healthcare services, which cover ~97% of the

population of Korea. NHIS data include information from all

hospitals, including inpatient and outpatient records, using the

International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related

Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes.

The NHIS database contains various types of

information, such as diagnosis, hospitalization and outpatient

treatments, medical expenses, prescribed medications, performed

surgeries, and patient demographics such as sex and age, as well as

the date of death when applicable. This information is stored based

on the content billed by the medical institutions. The database was

provided to researchers with all personal information, such as

names, resident registration numbers, addresses and phone numbers

anonymized or removed.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional

Review Board of Korea University Anam Hospital (Seoul, Korea; IRB

no. 2021AN0431).

Study population

The present study included patients diagnosed with

BTC between 2015 and 2020. BTC was defined as one of the following

primary diagnostic ICD-10 codes: C22.1 (intrahepatic BTC), C23.X

[gallbladder (GB) cancer], or C24.X (extrahepatic BTC). The date of

claim registration in the NHIS database was assumed to be the date

of diagnosis. Data from 2004 to 2014 were considered a washout

period to account for the absence of new drugs and to obtain

diagnostic data. Patients were included if they were aged ≥20 years

at the time of their first diagnosis of BTC and underwent surgery

within 1 year before or after the diagnosis, or were administered

gemcitabine hydrochloride or cisplatin following the diagnosis

(n=38,259). Among these, 24,659 patients who developed other types

of cancer following BTC were excluded, thus leaving a final cohort

of 13,600 patients for analysis.

Demographic variables, including age and sex were

also assessed. Previous medical history included diabetes,

hepatitis and gallstones. In the case that the corresponding

disease codes existed prior to the diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma,

they were considered part of the medical history.

The primary outcome variables were overall and

1-year mortality rates. The analyses included comparisons between

individuals who only underwent surgery and those who only received

medication, comparisons based on the year of diagnosis, comparisons

based on diagnosis codes, and analysis of mortality rates based on

the presence of diabetes, hepatitis, and gallstones.

In the case of individuals diagnosed with BTC, those

who underwent surgical treatment were defined with the code ‘Q7380,

Q7410, Q7342, Q7221, Q7222, Q7223, Q7224 and Q7225’. Among those

diagnosed with BTC, medications were defined using the medication

codes for ‘gemcitabine (164901BIJ, 164902BIJ, 164903BIJ, 164904BIJ,

164930BIJ, 164931BIJ and 164932BIJ)’ and ‘cisplatin (134501BIJ,

134502BIJ, 134503BIJ, 134504BIJ, 134505BIJ, 134530BIJ, 134531BIJ,

134532BIJ, 134533BIJ and 134534BIJ)’. For diabetes, the codes

R81.X, E10.X and E11.X were used; chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV)

was identified using B18.X; gallstones were identified using

K80.X.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as the mean ±

standard deviation, and categorical variables are presented as

frequencies and percentages. Cox proportional hazard regression

models were used to compare the risk of disease outcomes between

the groups, which allowed for the calculation of hazard ratios

(HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Before analyzing the Cox

model, a log-rank test was used on the Kaplan-Meier survival curves

to confirm differences among groups, where all groups exhibited a

P-value <0.05, thus satisfying the proportional hazards

assumption. This analysis was performed as an unadjusted analysis

without any adjustments. The reason for not using an adjusted

analysis is that the present study primarily focused on identifying

raw correlations. All statistical analyses were performed using the

SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute). All P-values were

two-sided, and a P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Study population

Data on patients who had been diagnosed with BTC

between 2015 and 2019 were collected from the NHID. Patients

diagnosed with other types of cancer were excluded from data

collection, resulting in a final cohort of 10,222 patients for

analysis. Among these patients, 2,614 patients (25.57%) had

intrahepatic BTC, 2,757 patients (26.97%) had extrahepatic BTC and

4,851 patients (47.46%) had GB cancer. The clinical profiles of the

final cohort are summarized in Table

I.

| Table IClinical characteristics and

comorbidities of the patients with BTC. |

Table I

Clinical characteristics and

comorbidities of the patients with BTC.

|

Characteristics | Patients

(n=10,222) |

|---|

| Age, years; mean

(SD) | 66.94 (11.58) |

| Sex | |

|

Male | 5,616 (54.94) |

|

Female | 4,606 (45.06) |

| Incidence year | |

|

2015 | 2,091 (20.46) |

|

2016 | 1,621 (15.86) |

|

2017 | 1,875 (18.34) |

|

2018 | 2,131 (20.85) |

|

2019 | 2,504 (24.50) |

| Medical

history | |

|

Diabetes

mellitus | 6,850 (67.01) |

|

Chronic

hepatitis B virus infection | 2,696 (26.38) |

|

Cholelithiasis | 5,668 (55.45) |

| Diagnosis of

BTC | |

|

Intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma | 2,614 (25.57) |

|

Gallbladder

cancer | 4,851 (47.46) |

|

Extrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma | 2,757 (26.97) |

The mean age of cohort was 66.94 (SD 11.58) years,

and 54.94% were male. Prior to being diagnosed with BTC, 67.01% of

the patients had diabetes mellitus, 26.38% had hepatitis, and

55.45% had GB stones.

Survival probability according to the

year of diagnosis

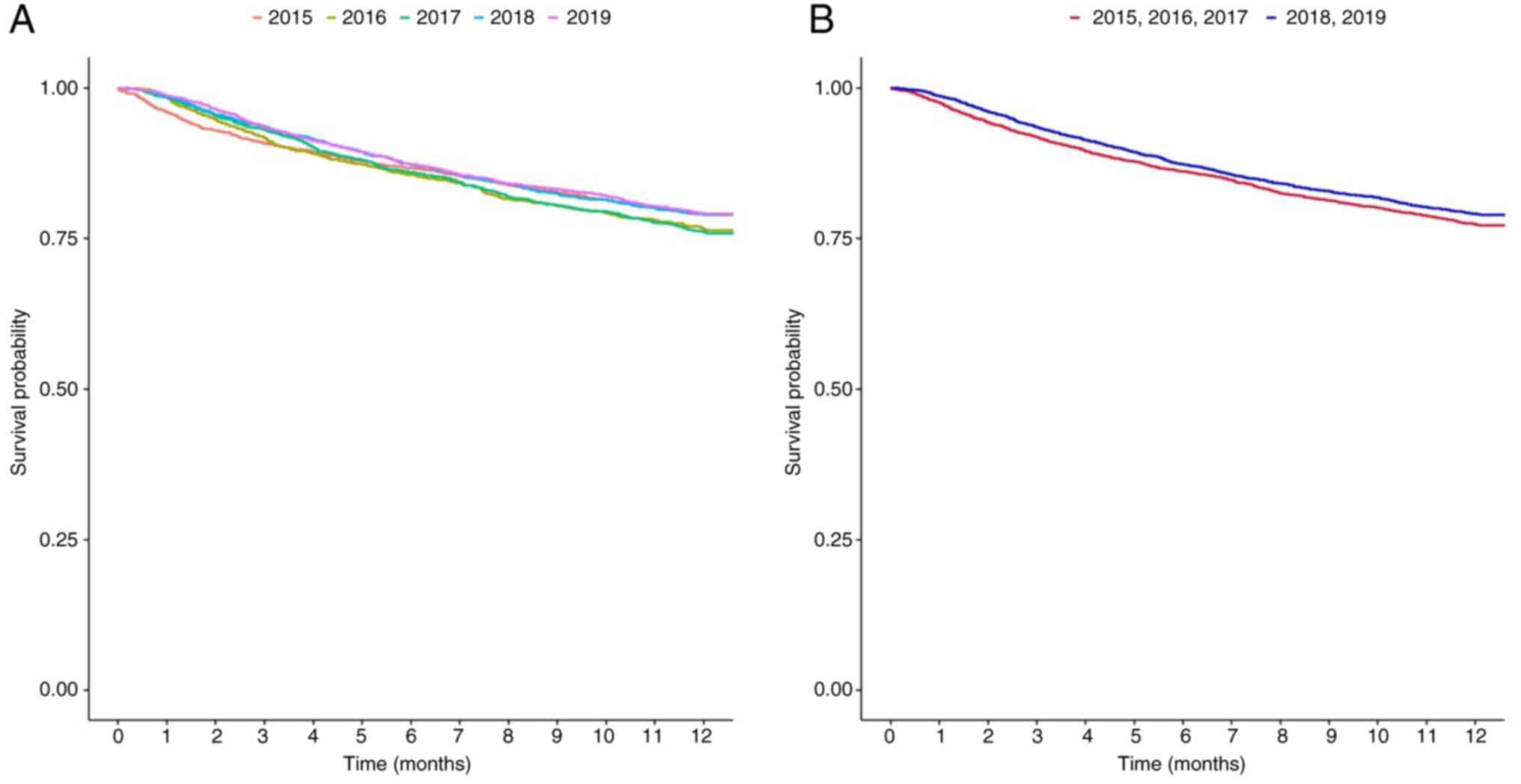

The HR of the 1-year survival rates of the patients

diagnosed each year are presented in Fig. 1 and Tables SI and SII: 1.133 (95% CI, 0.988-1.299) for 2016,

1.15 (95% CI, 1.008-1.311) for 2017, 0.992 (95% CI, 0.869-1.131)

for 2018, and 0.986 (95% CI, 0.868-1.119) for 2019, with 2015 set

as the reference year. Numerically, the 1-year survival rate of the

patients with BTC increased from 20.95% in 2015 to 24.11% in 2017,

and then decreased to 21.07% in 2018, as shown in Fig. 1A and Table SI. The HR of the 1-year survival

rate of the relatively recently diagnosed patients was lower than

that of the patients diagnosed earlier, and the difference was

statistically significant (HR, 0.908; 95% CI, 0.836-0.987;

P=0.0237) (Fig. 1B and Table SII). Table SII presents the P-value derived from

the univariate log-rank test, whereas the P-value reported in the

main text corresponds to that obtained from the Cox proportional

hazards model.

Survival probability according to

treatment setting

In the analysis of the treatment setting, to compare

surgery and chemotherapy, 491 patients who received no treatment

and 856 patients who underwent both surgery and chemotherapy were

excluded, resulting in a total of 10,222 patients being included in

the analysis. When the patients were categorized according to the

treatment they received for BTC, 9,451 patients received surgery

only, and 2,802 received chemotherapy only (Table II). The survival probability was

markedly lower in the chemotherapy-only group than in the

surgery-only group (HR, 4.857; 95% CI, 4.508-5234; P<0.001,

Fig. S1).

| Table IIOne-year survival rates of the

patients. |

Table II

One-year survival rates of the

patients.

| Treatment | No. of events/n

(%) | Log rank z-test

statistic | Log rank test

P-value | HR (95% CI) |

|---|

| Surgery only | 1,133/9,451

(11.99%) | 45.8484 | <0.0001 | Ref. |

| Chemotherapy

only | 1,485/2,802

(53.00%) | | | 4.857

(4.508-5.234) |

Survival probability according to

anatomic site

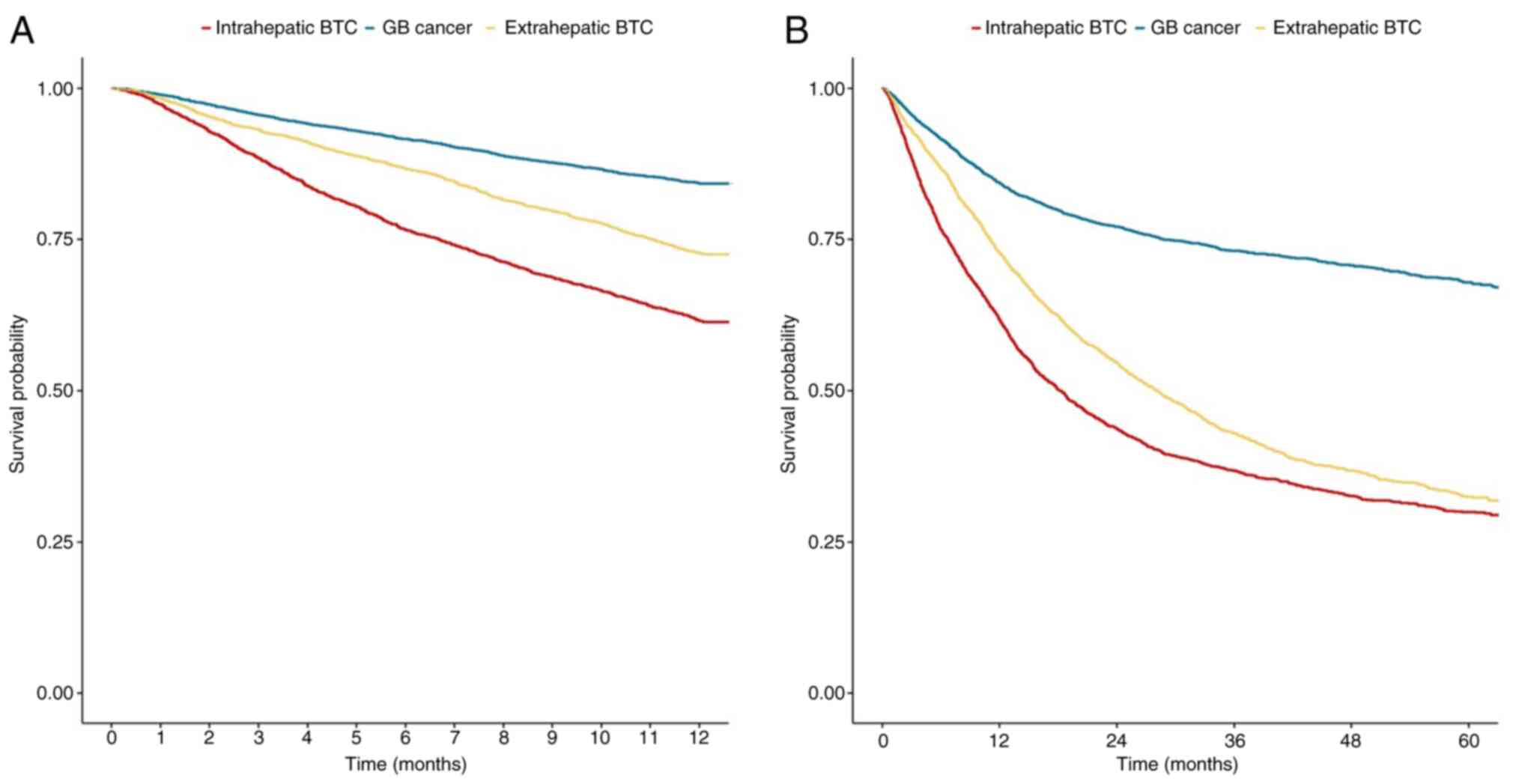

The survival rates of the patients categorized

according to anatomical tumor sites are presented in Fig. 2. The data for intrahepatic BTC,

extrahepatic BTC and GB cancer are also shown in (Tables SIII and SIV). The 1-year survival probability was

the lowest in GB cancer (HR, 0.349; 95% CI, 0.32-0.381;

P<0.001), followed by extrahepatic BTC (HR, 0.641; 95% CI,

0.589-0.698; P<0.001) when intrahepatic BTC was used as a

reference (Fig. 2A and Table SIII). The median survival

probability was not reached for intrahepatic BTC (Fig. 2B).

Survival probability according to

comorbidities

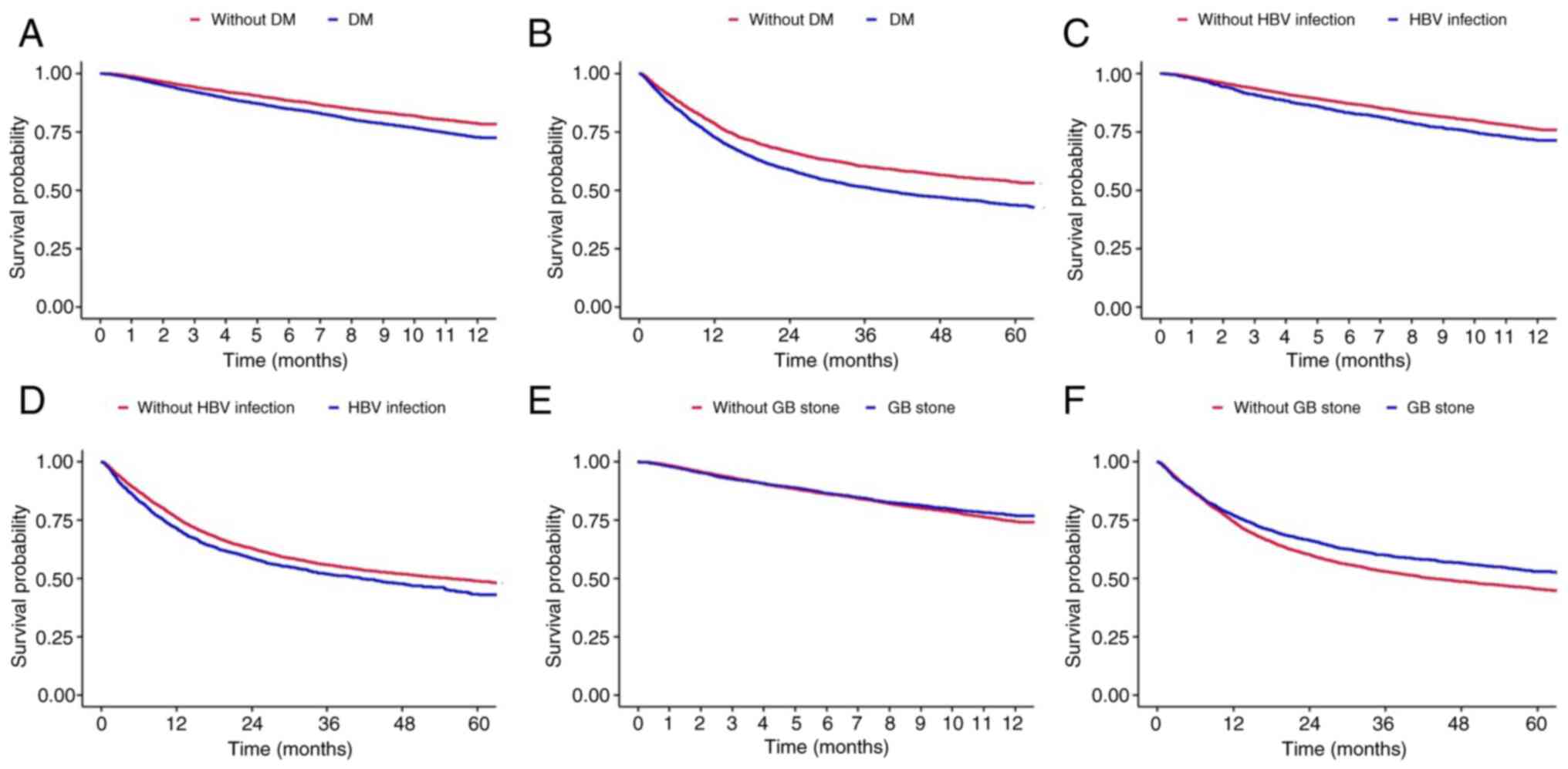

The present study conducted a subgroup analysis

according to the comorbidities of the patients with BTC (Fig. 3 and Table

SV, Table SVI, Table SVII, Table SVIII, Table SIX and Table SX). Patients who had been diagnosed

with diabetes mellitus prior to being diagnosed with BTC had a

poorer prognosis than those who had not (HR, 1.318; 95% CI,

1.225-1.418; P<0.001; Fig. 3A and

Table SV). The analysis of overall

survival revealed the same tendency (HR, 1.322; 95% CI,

1.252-1.397; P<0.001; Fig. 3B and

Table SVI). The median overall

survival of the patients without diabetes mellitus was 76.587

months (95% CI, 68.12-85.85), while that of the patients with

diabetes mellitus was 38.889 months (95% CI, 35.88-41.87) (Fig. 3B).

Patients who had chronic HBV infection also

exhibited a higher HR than patients who did not have HBV infection

(HR, 1.249; 95% CI, 1.147-1.36; P<0.001; Fig. 3C and Table SVII). The median overall survival of

the patients who had known HBV infection was 55.556 months (95% CI,

50.73-40.71; Fig. 3D). Patients with

known GB stones prior to being diagnosed with BTC had a decreased

risk of mortality (HR, 0.902; 95% CI, 0.834-0.976; P=0.01; Fig. 3E and F, and Table

SIX).

Discussion

The present study examined the 1-year survival of

patients diagnosed with BTC over a period of 5 years, beginning

from 2015. The present study investigated the impact of various

factors on the survival rates of patients with BTC. Consistent

yearly survival rates were observed with a slight decline after

2018. This decline was statistically significant when comparing the

pre- and post-2018 data. Intrahepatic BTC was associated with the

shortest survival time, whereas a history of diabetes or chronic

HBV infection negatively affected survival. However, cholelithiasis

was associated with an improved survival.

BTC is well known for its poor prognosis, with

patients with stage 4 disease having a 5-year survival rate

<10%.2 Several clinical characteristics contribute to this poor

prognosis: Diagnosis often occurs at an advanced stage due to the

absence of early symptoms, the heterogeneous nature of cancer with

a wide range of anatomies (from intrahepatic to the ampulla of

Vater) (1), and the limitation of

cytotoxic chemotherapy due to the lack of effective therapeutic

targets. While advancements in diagnostic techniques, active health

screening and the widespread adoption of genetic analyses, such as

next-generation sequencing have addressed numerous challenges

regarding BTC, the extent of the improvement in the prognosis of

patients with BTC remains elusive.

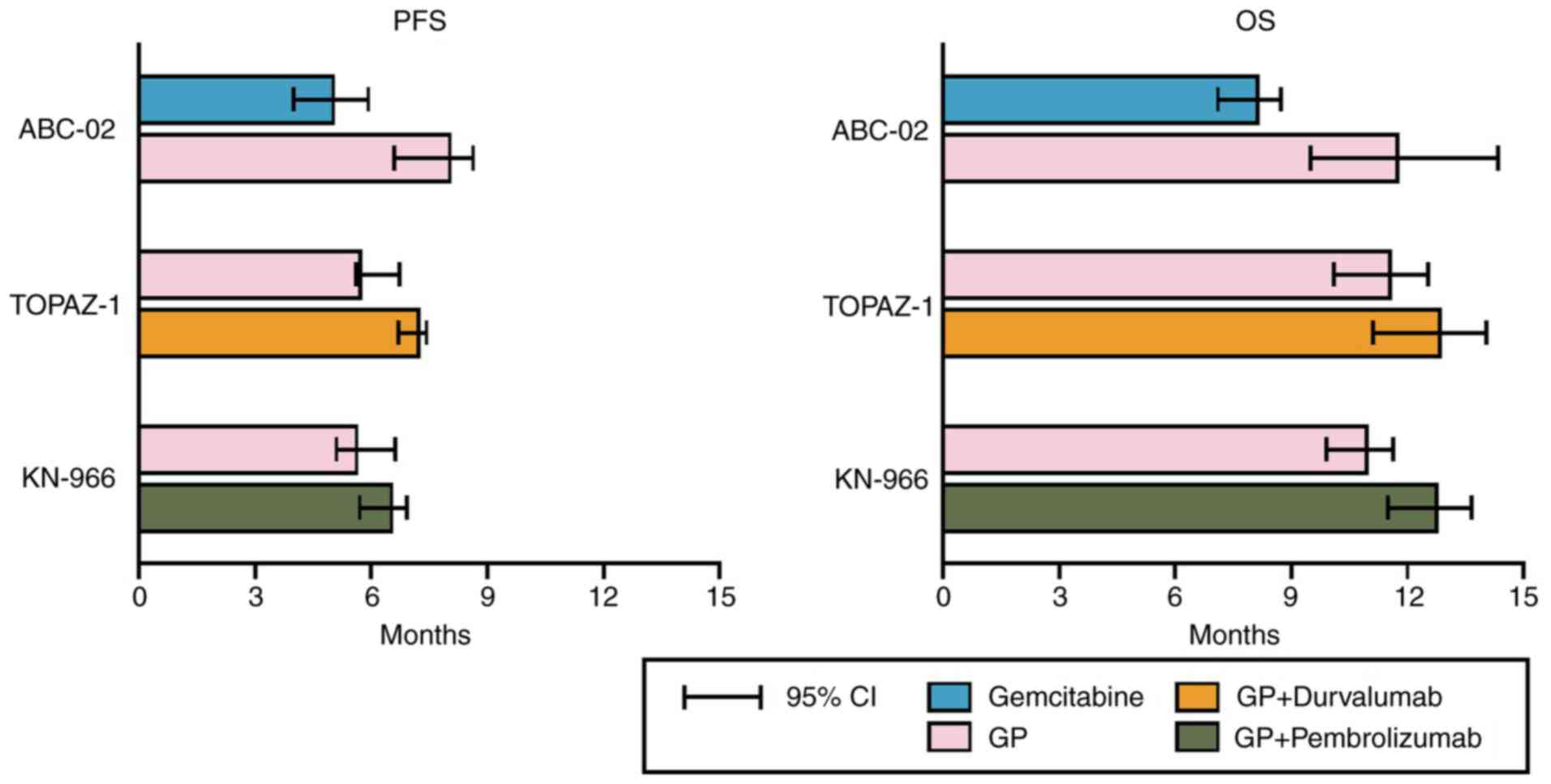

From a therapeutic perspective, combination therapy

using gemcitabine and cisplatin (GP) has been pivotal since 2010.

This combination has been shown to lead to improved response rates

and survival benefits over gemcitabine monotherapy (medial overall

survival, 11.7 vs. 8.1 months; HR, 0.64; P<0.001), establishing

a standard palliative treatment approach (11). Since then, for over a decade, no

treatment strategy has surpassed this combination therapy. A few

additional benefits of epidermal growth factor receptor and

vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitors have been

observed (12). It was not until

2022 that the addition of durvalumab to GP was proven to extend

survival (medial overall survival, 12.8 months) (13); subsequently, the combination with

pembrolizumab also began to yield promising results (medial overall

survival, 12.7 months, Fig. 4)

(14).

The absence of effective subsequent therapy

following the initial treatment also contributes to the poor

prognosis of patients with BTC. Based on a phase 2 clinical trial

published in 1998, fluorouracil (5-FU)-based regimens have been

widely used empirically (15);

however, owing to the rarity of the affected population, obtaining

well-designed phase 3 data has been challenging. Since 2014, the

ABC-06 trial has tested the FOLFOX regimen (5-FU, leucovorin and

oxaliplatin), eventually yielding the first positive data for a

second line therapeutic option in 2021(16).

However, in the era of precision oncology, BTC

treatments are evolving. A number of basic studies have identified

molecular targets that are potentially useful for target-directed

therapies, such as the fibroblast growth factor receptor

(FGFR), HER2, metabolic regulators, such as isocitrate

dehydrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH1/2), and

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit

alpha (17-21).

Among these, FGFR2-targeting agents (e.g., pemigatinib and

futibatinib) (22-24)

and IDH1-targeting agents (e.g., ivosidenib) have been approved by

the FDA (25,26). HER2 overexpression is also a major

treatment target in GB cancer (27),

and not only existing HER2-targeted agents (e.g., trastuzumab and

pertuzumab) (28,29), but also novel agents (e.g.,

zanidatamab) are being used for treatment (30). Ethnic differences in therapeutic

targets have been consistently reported (31), and particularly in Koreans, the

prevalence of IDH1/2 and FGFR2 aberrations is lower than that

typically reported (9). However,

with the widespread use of next-generation sequencing (NGS),

efforts to identify patients who could benefit from targeted

therapy are continuing, and the impact of these therapies on

prognosis is a subject that requires thorough investigation. Owing

to these efforts, the survival rates of patients with BTC are

steadily increasing, albeit at a gradual pace. Annual cancer

statistics in Korea have also reported that the 5-year relative

survival rate of patients with BTC exhibited an upward trend until

the period of 2011-2015 (29.1%) (32); however, from to 2015-2019 (28.5%), it

exhibited a decreasing tendency (-0.6%) (33). Based on our data, it is plausible

that these changes originated in 2018. Novel drugs, such as

nanoliposomal irinotecan (NIFTY) (34) and immune checkpoint inhibitor

clinical trials (TOPAZ-1 and KEYNOTE-966) (13,14),

have recruited patients in Korea since 2018. TOPAZ-1 and

KEYNOTE-966 demonstrated that a combination of immune checkpoint

inhibitors and chemotherapy significantly extended the survival

rates of patients with advanced BTC (13,14).

Continuous real-world follow-up studies are required to determine

the changes in the survival rates of patients with BTC following

immunotherapy in clinical settings.

Anatomical heterogeneity has long been a challenging

issue in BTC, with each cancer subtype exhibiting variable survival

rates. In the present study, the patients with intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma had the worst prognosis. This may be attributed

to its tendency to present with fewer symptoms, such as jaundice or

abdominal pain, leading to a delayed diagnosis. This finding aligns

with the research results from the study by Tawarungruang et

al (35), that tracked prognosis

following surgical treatment (median survival time 21.8 months in

distal cholangiocarcinoma vs. 12.4 months in intrahepatic

cholangiocarcinoma). Anatomical heterogeneity is closely associated

with molecular heterogeneity (36).

However, the difference in the response to chemotherapy among

anatomical subgroups in the ABC-02 and TOPAZ-1 trials was not

distinct (11,13), indicating the need for further

research in this area.

The subgroup analysis in the present study provided

several insights. Diabetes is a well-known risk factor of BTC

(37,38). In the present study, patients with

pre-diagnosed diabetes exhibited a significantly reduced overall

survival compared to those without diabetes (38.889 vs. 76.587

months). This suggests that diabetes not only functions as a risk

factor for the development of BTC, but also significantly affects

overall survival. Additionally, it was observed that patients with

a history of cholelithiasis had an extended survival compared with

those without. Regular follow-up sessions for known GB stones and

the early detection of cancer due to symptoms, leading to prompt

treatment, are considered to have contributed to the prolonged

survival of these patients. However, the present study identified

data-driven phenomena, not biological mechanisms, necessitating

cautious interpretation. Further in vivo and prospective

studies are required to validate these findings.

The present study had several limitations, which

should be mentioned. The present study was unable to obtain

information on the clinical or pathological stages of cancer, which

significantly affect survival and prognosis. The authors attempted

to overcome this limitation through precise operational definitions

by using various treatments. NHIS research utilizes data based on

insurance claims, which means that data for items not covered by

insurance are not provided. Additionally, sensitive data that could

identify patients were not disclosed to protect personal

information, such as family history or socioeconomic status.

Detailed medical information specific to particular test results or

specific medical conditions was unavailable for research purposes.

Nevertheless, the lack of information was not concentrated in any

one subgroup, but was applied to all subjects, which the authors

believe lends value to the results as a gross outcome of

macroscopic trends from big data.

In conclusion, the present study tracked the

survival trends of patients with BTC using national healthcare big

data, suggesting an improvement in the overall prognosis of

patients with BTC since 2018. Additionally, it was revealed that

the prognosis of patients with BTC varies depending on the anatomic

site of the cancer, as well as the presence of underlying diseases,

despite the absence of detailed pathologic information.

Supplementary Material

Survival probability of patients

treated with chemotherapy only and surgery only.

One-year survival rates of the

patients (Fig. 1A).

One-year survival rates of the

patients (Fig. 1B).

One-year survival rates of the

patients (Fig. 2A).

Overall survival rates of the patients

(Fig. 2B).

One-year survival rates of the

patients (Fig. 3A).

Overall survival rates of the patients

(Fig. 3B).

One-year survival rates of the

patients (Fig. 3C).

Overall survival rates of the patients

(Fig. 3D).

One-year survival rates of the

patients (Fig. 3E).

Overall survival rates of the patients

(Fig. 3F).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by a grant of from

Korea University (grant no. K2314161).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

Both authors (JYL and JWK) contributed to the

conception and design of the study. The data were collected by JYL.

JYL and JWK performed data analysis and figure visualization. JWK

wrote the first draft of the manuscript and both authors commented

on the previous version of the manuscript. JYL and JWK authors

confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All the authors

have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

All study procedures followed the ethical standards

of the responsible committee on human experimentation

(institutional and national) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1964

and later versions. The study protocol was approved by the

Institutional Review Board of Korea University Anam Hospital

(Seoul, Korea; IRB no. 2021AN0431). The data used in the present

study were obtained from the National Health Insurance Service

(NHIS) of Korea. The database was provided to researchers with all

personal information, such as names, resident registration numbers,

addresses and phone numbers anonymized or removed.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Valle JW, Kelley RK, Nervi B, Oh DY and

Zhu AX: Biliary tract cancer. Lancet. 397:428–444. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kang MJ, Jung KW, Bang SH, Choi SH, Park

EH, Yun EH, Kim HJ, Kong HJ, Im JS and Seo HG: Community of

population-based regional cancer registries*. Cancer statistics in

Korea: Incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2020.

Cancer Res Treat. 55:385–399. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lee J, Park SH, Chang HM, Kim JS, Choi HJ,

Lee MA, Jang JS, Jeung HC, Kang JH, Lee HW, et al: Gemcitabine and

oxaliplatin with or without erlotinib in advanced biliary-tract

cancer: A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study.

Lancet Oncol. 13:181–188. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ, Oh CM, Seo HG

and Lee JS: Cancer statistics in Korea: Incidence, mortality,

survival and prevalence in 2010. Cancer Res Treat. 45:1–14.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Banales JM, Marin JJG, Lamarca A,

Rodrigues PM, Khan SA, Roberts LR, Cardinale V, Carpino G, Andersen

JB, Braconi C, et al: Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: The next horizon in

mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol.

17:557–588. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Shi Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, Niu K, Mao X, Feng

K and Zhang Y: N6-methyladenosine with immune infiltration and

PD-L1 in hepatocellular carcinoma: novel perspective to

personalized diagnosis and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

14(1153802)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Deng M, Li SH, Fu X, Yan XP, Chen J, Qiu

YD and Guo RP: Relationship between PD-L1 expression, CD8+ T-cell

infiltration and prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

patients. Cancer Cell Int. 21(371)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Xie Q, Wang L and Zheng S: Prognostic and

clinicopathological significance of PD-L1 in patients with

cholangiocarcinoma: A meta-analysis. Dis Markers.

2020(1817931)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Lee J and Kim DU: Recent Update of

Targeted Therapy in Cholangiocarcinoma. Korean J Pancreas Biliary

Tract. 28:59–66. 2023.(In Korean).

|

|

10

|

Dey S, Chatterjee S, Ghosh S and Sikdar N:

The geographical, ethnic variations and risk factors of gallbladder

carcinoma: A worldwide view. J Investig Genomics. 3:49–54.

2016.

|

|

11

|

Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D,

Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira

SP, et al: Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for

biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 362:1273–1281. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Guion-Dusserre JF, Lorgis V, Vincent J,

Bengrine L and Ghiringhelli F: FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as a

second-line therapy for metastatic intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

World J Gastroenterol. 21(2096)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Oh DY, Ruth He A, Qin S, Chen LT, Okusaka

T, Vogel A, Kim JW, Suksombooncharoen T, Ah Lee M, Kitano M, et al:

Durvalumab plus gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced biliary tract

cancer. NEJM Evid. 1(EVIDoa2200015)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kelley RK, Ueno M, Yoo C, Finn RS, Furuse

J, Ren Z, Yau T, Klümpen HJ, Chan SL, Ozaka M, et al: Pembrolizumab

in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin compared with

gemcitabine and cisplatin alone for patients with advanced biliary

tract cancer (KEYNOTE-966): A randomised, double-blind,

placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 401:1853–1865.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Sanz-Altamira PM, Ferrante K, Jenkins RL,

Lewis WD, Huberman MS and Stuart KE: A phase II trial of

5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, and carboplatin in patients with

unresectable biliary tree carcinoma. Cancer. 82:2321–2325.

1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Lamarca A, Palmer DH, Wasan HS, Ross PJ,

Ma YT, Arora A, Falk S, Gillmore R, Wadsley J, Patel K, et al:

Second-line FOLFOX chemotherapy versus active symptom control for

advanced biliary tract cancer (ABC-06): A phase 3, open-label,

randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 22:690–701.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

O'Rourke CJ, Munoz-Garrido P and Andersen

JB: Molecular targets in cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatology. 73 (Suppl

1):S62–S74. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Goyal L, Saha SK, Liu LY, Siravegna G,

Leshchiner I, Ahronian LG, Lennerz JK, Vu P, Deshpande V,

Kambadakone A, et al: Polyclonal secondary FGFR2 mutations drive

acquired resistance to FGFR inhibition in patients with FGFR2

fusion-positive cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Discov. 7:252–263.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Javle M, Churi C, Kang HC, Shroff R, Janku

F, Surapaneni R, Zuo M, Barrera C, Alshamsi H, Krishnan S, et al:

HER2/neu-directed therapy for biliary tract cancer. J Hematol

Oncol. 8(58)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Riener MO, Bawohl M, Clavien PA and Jochum

W: Rare PIK3CA hotspot mutations in carcinomas of the biliary

tract. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 47:363–367. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Moeini A, Sia D, Bardeesy N, Mazzaferro V

and Llovet JM: Molecular pathogenesis and targeted therapies for

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 22:291–300.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Abou-Alfa GK, Sahai V, Hollebecque A,

Vaccaro G, Melisi D, Al-Rajabi R, Paulson AS, Borad MJ, Gallinson

D, Murphy AG, et al: Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally

advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: A multicentre,

open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 21:671–684.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Makawita S, K Abou-Alfa G, Roychowdhury S,

Sadeghi S, Borbath I, Goyal L, Cohn A, Lamarca A, Oh DY, Macarulla

T, et al: Infigratinib in patients with advanced cholangiocarcinoma

with FGFR2 gene fusions/translocations: the PROOF 301 trial. Future

Oncol. 16:2375–2384. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Rizzo A, Ricci AD and Brandi G:

Futibatinib, an investigational agent for the treatment of

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Evidence to date and future

perspectives. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 30:317–324.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Abou-Alfa GK, Macarulla T, Javle MM,

Kelley RK, Lubner SJ, Adeva J, Cleary JM, Catenacci DV, Borad MJ,

Bridgewater J, et al: Ivosidenib in IDH1-mutant,

chemotherapy-refractory cholangiocarcinoma (ClarIDHy): A

multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3

study. Lancet Oncol. 21:796–807. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Cho SM, Esmail A, Raza A, Dacha S and

Abdelrahim M: Timeline of FDA-approved targeted therapy for

cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 14(2641)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Roa I, de Toro G, Schalper K, de

Aretxabala X, Churi C and Javle M: Overexpression of the HER2/neu

gene: A new therapeutic possibility for patients with advanced

gallbladder cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 7:42–48.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yarlagadda B, Kamatham V, Ritter A,

Shahjehan F and Kasi PM: Trastuzumab and pertuzumab in circulating

tumor DNA ERBB2-amplified HER2-positive refractory

cholangiocarcinoma. NPJ Precis Oncol. 3(19)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lee CK, Chon HJ, Cheon J, Lee MA, Im HS,

Jang JS, Kim MH, Park S, Kang B, Hong M, et al: Trastuzumab plus

FOLFOX for HER2-positive biliary tract cancer refractory to

gemcitabine and cisplatin: A multi-institutional phase 2 trial of

the Korean cancer study group (KCSG-HB19-14). Lancet Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 8:56–65. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Harding JJ, Fan J, Oh DY, Choi HJ, Kim JW,

Chang HM, Bao L, Sun HC, Macarulla T, Xie F, et al: Zanidatamab for

HER2-amplified, unresectable, locally advanced or metastatic

biliary tract cancer (HERIZON-BTC-01): A multicentre, single-arm,

phase 2b study. Lancet Oncol. 24:772–782. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Tsilimigras DI, Stecko H,

Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I and Pawlik TM: Racial and sex differences

in genomic profiling of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg

Oncol. 31:9071–9078. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Jung KW, Won YJ, Kong HJ and Lee ES:

Community of Population-Based Regional Cancer Registries. Cancer

statistics in Korea: Incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence

in 2015. Cancer Res Treat. 50:303–316. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Kang MJ, Won YJ, Lee JJ, Jung KW, Kim HJ,

Kong HJ, Im JS and Seo HG: Community of Population-Based Regional

Cancer Registries. Cancer statistics in Korea: Incidence,

mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2019. Cancer Res Treat.

54:330–344. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Yoo C, Kim KP, Jeong JH, Kim I, Kang MJ,

Cheon J, Kang BW, Ryu H, Lee JS, Kim KW, et al: Liposomal

irinotecan plus fluorouracil and leucovorin versus fluorouracil and

leucovorin for metastatic biliary tract cancer after progression on

gemcitabine plus cisplatin (NIFTY): A multicentre, open-label,

randomised, phase 2b study. Lancet Oncol. 22:1560–1572.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Tawarungruang C, Khuntikeo N, Chamadol N,

Laopaiboon V, Thuanman J, Thinkhamrop K, Kelly M and Thinkhamrop B:

Survival after surgery among patients with cholangiocarcinoma in

Northeast Thailand according to anatomical and morphological

classification. BMC Cancer. 21(497)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Hang H, Jeong S, Sha M, Kong D, Xi Z, Tong

Y and Xia Q: Cholangiocarcinoma: anatomical location-dependent

clinical, prognostic, and genetic disparities. Ann Transl Med.

7(744)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Ren HB, Yu T, Liu C and Li YQ: Diabetes

mellitus and increased risk of biliary tract cancer: Systematic

review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 22:837–847.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Schlesinger S, Aleksandrova K, Pischon T,

Jenab M, Fedirko V, Trepo E, Overvad K, Roswall N, Tjønneland A,

Boutron-Ruault MC, et al: Diabetes mellitus, insulin treatment,

diabetes duration, and risk of biliary tract cancer and

hepatocellular carcinoma in a European cohort. Ann Oncol.

24:2449–2455. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|