Introduction

Endoscopic resection is currently accepted as an

appropriate treatment method for early-stage colorectal cancer

(eCRC). Intramucosal CRC does not metastasize to the lymph nodes

and can be curatively removed by endoscopic resection (1,2). By

contrast, 6-12% of invasive eCRC cases, in which CRC invades

through the muscularis mucosae (MM), but does not extend into the

muscularis propria (MP), are associated with lymph node metastasis,

thus requiring additional colectomy/proctectomy and lymph node

dissection for curative treatment (3-6).

eCRC is grossly classified as a superficial type

(type 0), which is further divided into protruded type (type 0-I)

and superficial type (type 0-II) according to the Japanese

Classification of Colorectal, Appendiceal, and Anal Carcinoma,

third English edition, published in 2019 by the Japanese Society

for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum (JSCCR). This is referred to as

the JSCCR rule hereafter (7). The

protruded type can be further subclassified as the pedunculated

type (type 0-Ip), subpedunculated type (type 0-Isp), or sessile

type (type 0-Is) from the presence or absence of a pedicle

(7), while the Paris classification

states that the subpedunculated type should be managed in the same

manner as the sessile type (8). The

JSCCR project study revealed that the nodal metastasis rate of eCRC

with a submucosal (SM) invasion ≥1,000 µm was 12.5% (9). Additional surgery may be warranted in

patients with a SM invasion ≥1,000 µm when other risk factors for

lymph node metastasis are present, such as lymphovascular invasion,

poorly or undifferentiated component (poorly differentiated

adenocarcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell

carcinoma), muconodules at the invasion front, or high grade of

tumor budding/sprouting (BD) (10-12).

The depth of SM invasion is simply determined in sessile type

cases; however, it is relatively complex in the pedunculated type

due to the presence of stalks and tangled MM. In Western countries,

the Haggitt classification is used to determine the depth of SM

invasion. This system classifies head invasion [Haggitt level (HL)

1 and HL2] and stalk invasion (HL3) as a shallow SM invasion that

is equivalent to a SM invasion <1,000 µm in sessile lesions

(13-15),

while SM invasion of the underlying bowel wall (HL4) is recognized

as a risk factor of synchronous lymph node metastasis and the need

for additional surgical resection (16-19).

By contrast, the JSCCR rule has stated that the depth of SM

invasion should be measured from the MM lower border when the MM

can be identified or estimated and from the surface of the lesion

when it cannot be identified or estimated, irrespective of

macroscopic types. In an MM-tangled pedunculated lesion, the depth

of SM invasion should be measured from the reference line (7). With the JSCCR rule, additional surgery

may be considered in some pedunculated eCRC cases with head and

stalk invasion in which additional surgery can be spared by the

Haggitt classification method.

The present study aimed to validate the JSCCR rule

of measuring the SM depth in pedunculated-type eCRC cases, and to

subsequently compare its utility in considering the need for

additional surgery with that of the Haggitt classification

method.

Materials and methods

Patients and study subjects

Consecutive patients with pedunculated-type eCRC who

underwent endoscopic cold snare polypectomy or endoscopic mucosal

resection at Shioya Hospital, International University of Health

and Welfare (IUHW; Yaita, Japan) between 2006 and 2022 and Ota

Memorial Hospital (OMH), SUBARU Health Insurance Society (Ota,

Japan) between 2014 and 2022 were included in this study. The

exclusion criteria included having a history of invasive CRC within

5 years of endoscopic resection, concurrent invasive CRCs that were

resected soon after the endoscopic resection of pedunculated

lesions, unavailable clinical information and surveillance <100

days following endoscopic resection. Any eCRC cases with HL ≥1 in

which contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) was not

performed following endoscopic resection were also excluded.

Clinicopathological information was obtained through the electronic

chart systems of the respective institutions. When the

adenocarcinoma was intraepithelial carcinoma or was confined within

the lamina propria mucosae (LPM) and had negative resection

margins, the patients were recommended to undergo a colonoscopy in

12 months. When the adenocarcinoma invaded beyond the MM, but had

negative resection margins, the patients were followed-up every 6

months at the outpatient clinic for 5 years following endoscopic

resection. Serum tumor marker levels, such as carcinoembryonic

antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, were measured every 6

months. CECT was performed immediately or after 6 months at the

discretion of the clinicians and at 12 months following endoscopic

resection. Colonoscopy was performed at 6 or 12 months following

endoscopic resection at the discretion of the clinicians. In cases

of carcinoma-positive resection margins, positive lymphovascular

invasion and a SM invasion of ≥1,000 µm, additional surgery was

considered. The present study was conducted in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki, and the study protocol was approved by the

Ethical Review Boards of the participating hospitals: IUHW,

approval number: FK-94; OMH, approval number: OR24029. Due to the

retrospective design of the study and anonymization of the data,

consent to participate was not necessary.

Pathological examination

All specimens were routinely processed for

pathological diagnosis. The tumor size (maximal diameter),

histological type and BD were evaluated using hematoxylin and eosin

(H&E)-stained sections. Desmin protein staining was examined

using immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays, as needed, to measure the

distance of SM invasion. Elastica-van Gieson (EVG) staining and

CD34 IHC assays, if necessary, were used to evaluate venous

invasion, while D2-40 IHC assays were used to determine lymphatic

invasion. Briefly, resected specimens were rapidly fixed in 10%

neutral-buffered formalin solution for 24-48 h and embedded in a

paraffin block. The blocks were then cut into 3-µm-thick sections

for H&E and EVG staining, while they were cut into 4-µm-thick

sections for IHC. Primary antibodies for IHC were FLEX monoclonal

mouse anti-human desmin antibody (clone D33, 1:1; cat. no. IR606;

Dako; Agilent Technologies, Inc.), mouse monoclonal anti-podoplanin

antibody (clone D2-40, 1:1; cat. no. 760-4395; Ventana Medical

Systems, Inc.), and CONFIRM™ anti-CD34 mouse monoclonal antibody

(clone QBEnd/10, 1:1; cat. no. 790-2927; Ventana Medical Systems,

Inc.). Antigen retrieval was performed as needed, by heating in

Cell Conditioning Solution 1 (CC1) (Roche Diagnostics) at 100˚C for

60 min. Staining was performed on the VENTANA Benchmark XT

automated slide stainer (Leica Microsystems GmbH) in combination

with the ultraView DAB universal kit (Roche Diagnostics)

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nuclei were then

counterstained with hematoxylin (Sakura Finetek Japan Co., Ltd.).

Clinicopathological classification and staging were performed using

the World Health Organization classification of colorectal tumors

(5th edition) and the Union for International Cancer Control tumor,

node, metastasis staging system (8th edition) (20,21). In

addition, the subclassification of pathological tumor (pT)1 (the

tumor is confined within the SM) was performed using the JSCCR rule

with the following modifications: The Haggitt line, which links the

junctions between the tumor and non-tumor in the stalk, was used to

measure the depth of SM invasion instead of the reference line,

which was defined by the JSCCR rule as the boundary between the

tumor head and stalk (7) (Fig. 1A). pT1a and pT1b denote a SM invasion

of <1,000 and ≥1,000 µm, respectively (7). BD was evaluated according to the JSCCR

rule.

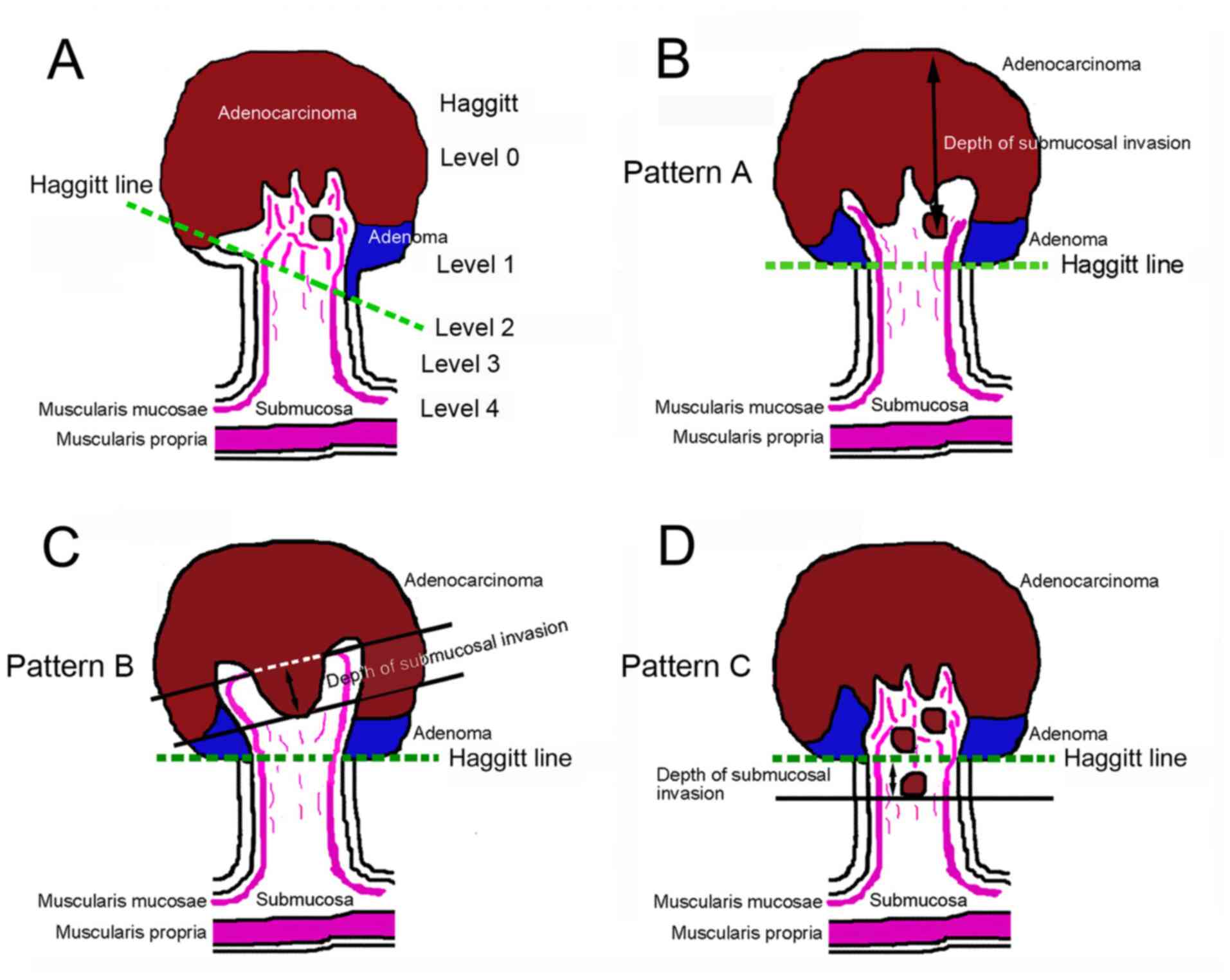

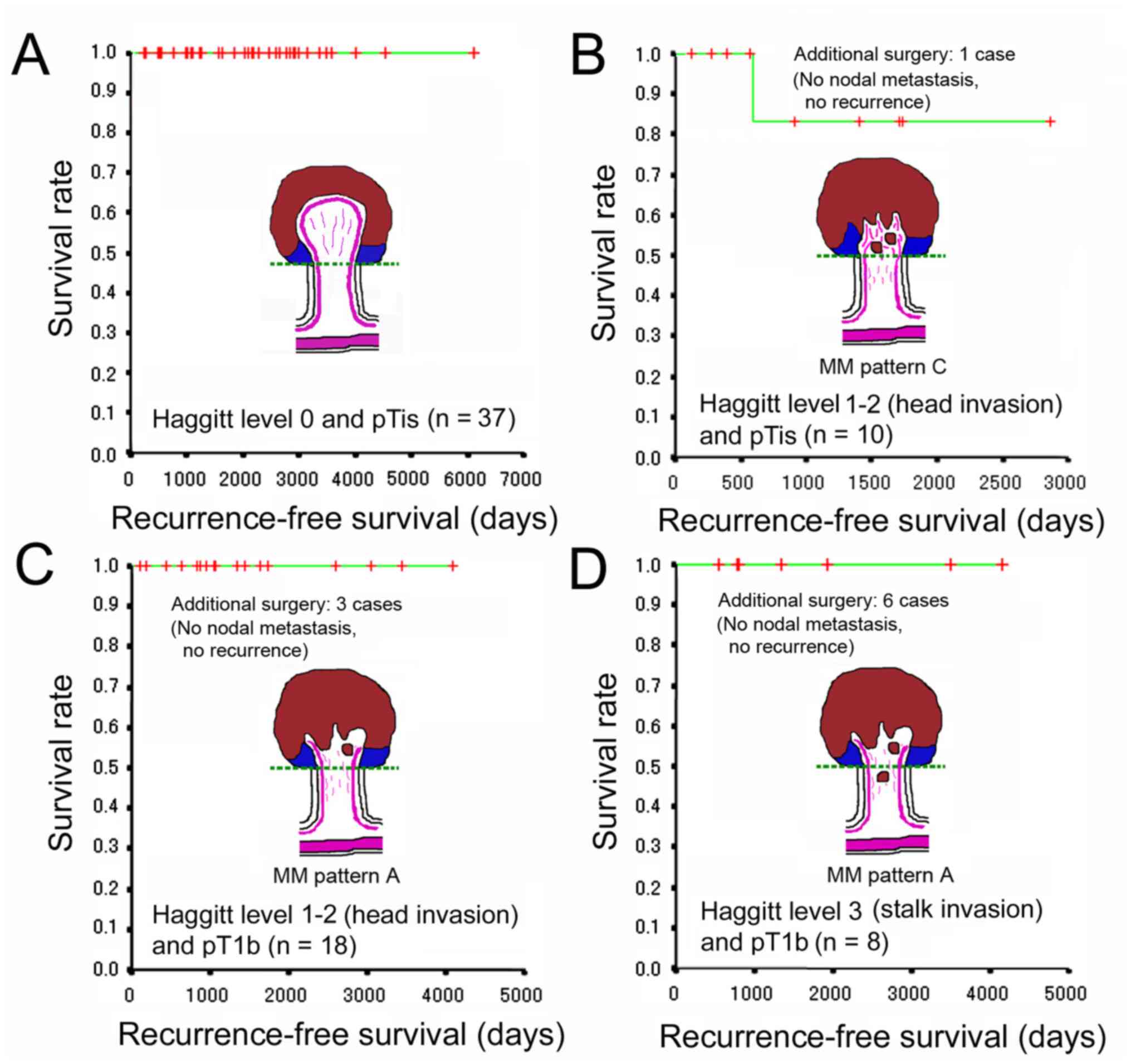

| Figure 1Method used for measuring the depth of

SM invasion in pedunculated-type eCRC. (A) The Haggitt line, which

links the junctions between the tumor and its stalk, was used to

measure the depth of SM invasion rather than the reference line,

which is defined by the JSCCR rule as the boundary between the

tumor head and stalk. (B) When the MM could not be identified or

estimated at the adenocarcinoma invasive front (designated as

pattern A), the depth of SM invasion was measured from the lesion's

surface. (C) If the MM could be identified or estimated in the

original form (designated as pattern B), then the depth of SM

invasion was measured from the lower border of MM. (D) When tangled

MM was observed (designated as pattern C), depth of SM invasion was

measured as the distance of invasion in the stalk beyond the

Haggitt line. eCRC, early colorectal cancer; JSCCR, Japanese

Society for Cancer of the Colon and Rectum; MM, muscularis mucosae;

SM, submucosal. |

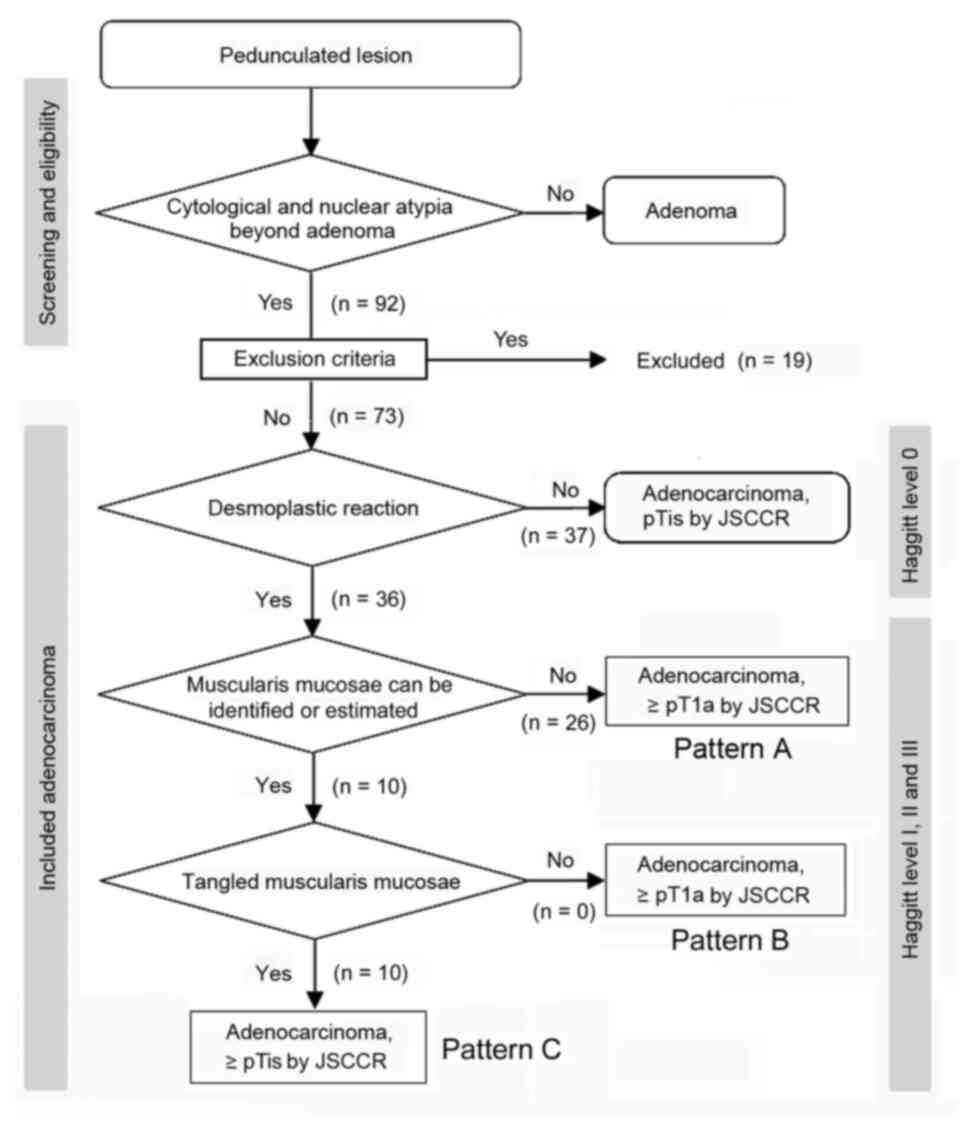

The flow diagram of the pathological staging of

pedunculated-type adenocarcinoma is presented in Fig. 2. Non-cancer glands often display SM

misplacement or pseudoinvasion in pedunculated-type tumors.

Therefore, submucosally placed glands were evaluated as

pseudoinvasion when they did not display cytological or nuclear

atypia strong enough for malignancy (Fig. 3A and B). In addition, the present study focused

on desmoplastic reaction, with adenocarcinoma cases without

desmoplastic reaction being diagnosed as intraepithelial carcinoma

or carcinoma confined within the LPM, corresponding to HL0 and pTis

by the JSCCR rule (22) (Fig. 3C and D). Adenocarcinoma cases with desmoplastic

reaction were staged as HL ≥1, which may be equivalent to pTis or

pT1 by the JSCCR rule (7).

Identification of the MM is pivotal for measuring the depth of SM

invasion and pT1 substaging by the JSCCR rule. Although the MM can

be easily identified on the H&E- and EVG-stained sections by

experienced pathologists (Fig. 3E to

H), it may be sometimes difficult to

distinguish between a tangled MM and carcinoma-associated fibrosis

(23,24). Desmin IHC assays were performed in

such cases. When the MM could not be identified or estimated at the

adenocarcinoma invasive front (pattern A) (Fig. 1B), the depth of SM invasion was

measured from the surface of the lesion (Fig. 4A and B). These cases were staged as ≥pT1a and HL

≥1. When the original MM could be identified or estimated, the

depth of SM invasion was measured from the lower border of the MM

(pattern B) (Fig. 1C). In such

cases, the lesions were staged as ≥pT1a and HL ≥1. When a tangled

MM was observed (pattern C) (Fig.

1D), the depth of SM invasion was measured as the distance of

invasion in the stalk beyond the Haggitt line (Fig. 4C and D). The SM depth of head invasion is deemed

to be <0 mm and the JSCCR rule specifies that such cases should

be described only as head invasion. Thus, cases of head invasion

with MM pattern C are practically treated as pTis. In the present

study, cases with MM pattern C are described as ≥pTis and HL ≥1.

Pathological diagnosis was independently performed by two

experienced pathologists, with diagnostic discordance resolved by

their discussion.

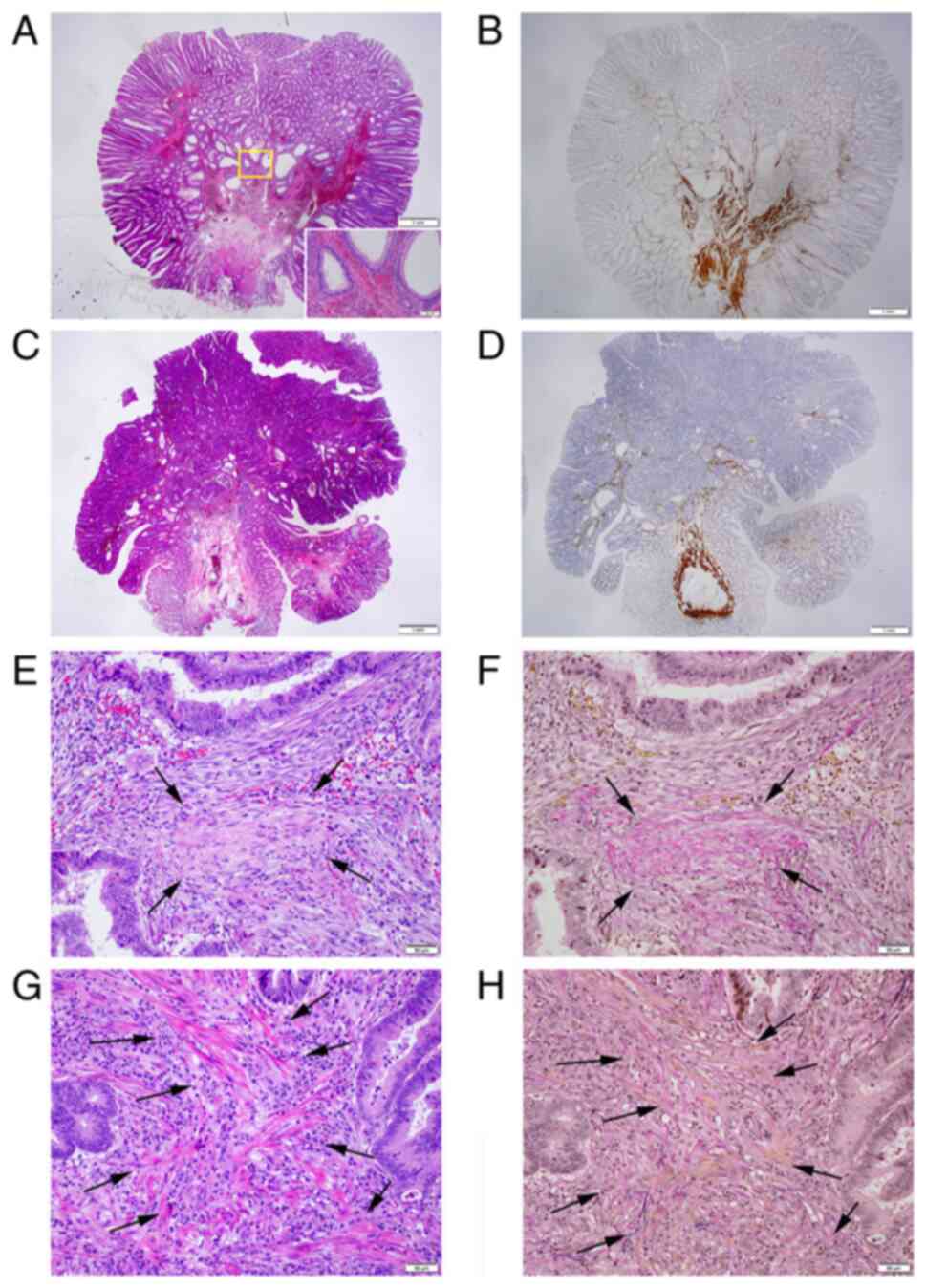

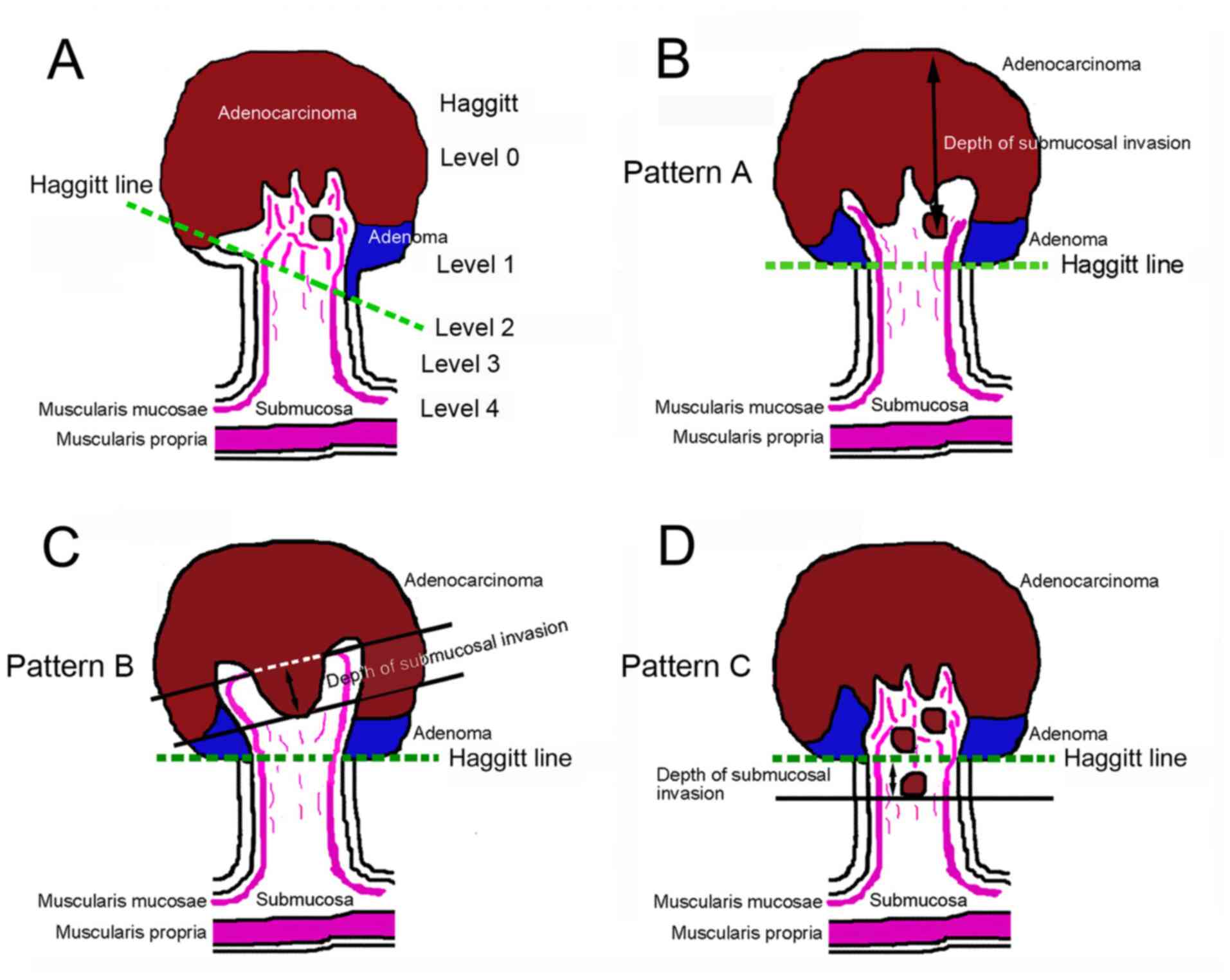

| Figure 3Pitfalls in cancer diagnosis, pT

staging and discrimination between desmoplastic reaction and a

tangled MM. (A) Representative histopathology of pedunculated-type

tubular adenoma displaying SM pseudoinvasion of adenomatous glands

(H&E; magnification, x1.25); Inset: Area within the yellow

square. Pseudoinvasive glands lack cytological atypia strong enough

for malignancy (H&E; magnification, x10). (B) Desmin IHC assays

demonstrate a tangled MM in the pedunculated-type tubular adenoma

(magnification, x1.25). (C) Pedunculated-type adenocarcinoma

initially appearing to present with head invasion with

disappearance of the MM. However, closer examination demonstrated

no desmoplastic reaction (case no. 58; H&E; magnification,

x1.25). (D) Desmin IHC assays demonstrated a tangled MM. This case

was ultimately evaluated as pTis/HL0 (magnification, x1.25). (E)

Desmoplastic reaction. Dull pink spindle cells, specifically

immature fibroblasts, irregularly proliferate with an edematous and

myxoid background and with collagen fibers deposited in the center

(arrows) (H&E; magnification, x20). (F) Desmoplastic reaction

foci with collagen fiber deposit are stained red using the EVG

staining (arrows; magnification, x20). (G) Tangled MM. Clear pink

spindle cells (arrows), specifically smooth muscle cells, run in

thin bundles (H&E; magnification, x20). (H) Smooth muscle cell

bundles (arrows) are stained yellow using the EVG staining

(magnification, x20). EVG, Elastica-van Gieson; H&E,

hematoxylin and eosin; HL, Haggitt level; IHC,

immunohistochemistry; MM, muscularis mucosae; pT, pathological

tumor; pTis, intraepithelial carcinoma or carcinoma confined within

the lamina propria mucosae; SM, submucosal. |

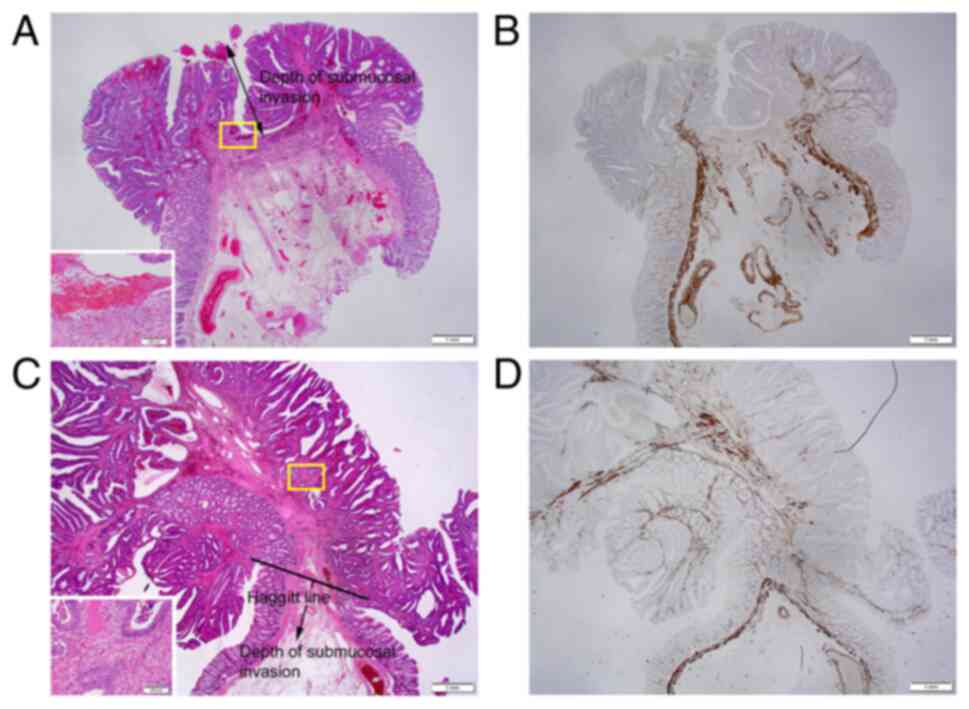

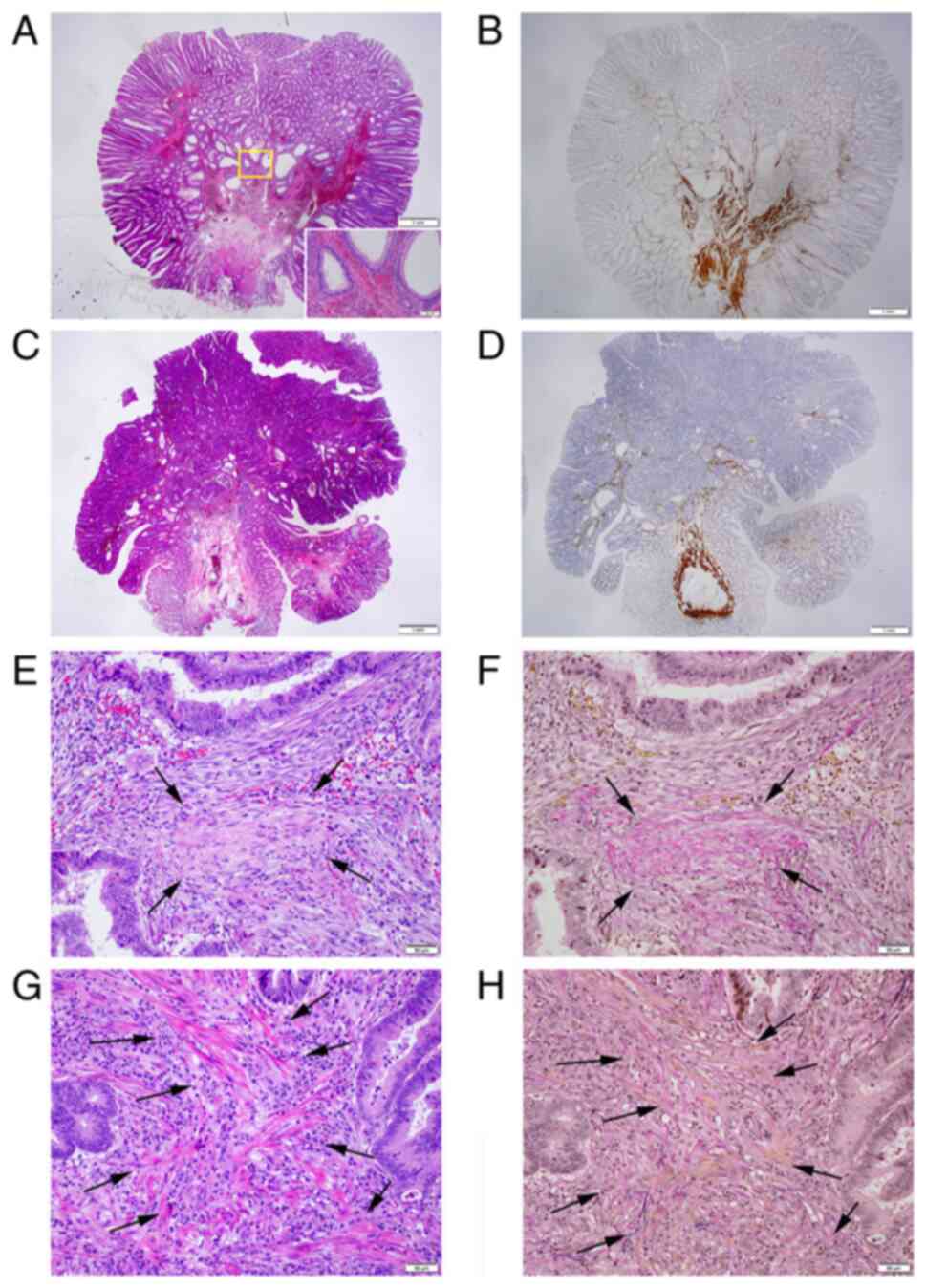

| Figure 4Representative histopathology of the

MM pattern in pedunculated-type eCRC cases. (A) When the MM could

not be identified or estimated at the adenocarcinoma invasive front

(designated as pattern A), the depth of SM invasion was measured

from the lesion's surface (H&E; magnification, x1.25); Inset:

Area within the yellow square. Desmoplastic reaction at the tumor

front, suggesting cancer invasion (H&E; magnification, x10;

case no. 74). (B) Desmin IHC assays demonstrated the disappearance

of the MM at the invasive front (magnification, x1.25). (C) When a

tangled MM was observed at the adenocarcinoma invasive front

(designated as pattern C), the depth of SM invasion was measured as

the distance of invasion in the stalk beyond the Haggitt line

(H&E; magnification, x1.25); Inset: Area within the yellow

square. Desmoplastic reaction at the tumor front, suggesting cancer

invasion (H&E; magnification, x10; case no. 41). (D) Desmin IHC

assays demonstrated a tangled MM at the invasive front

(magnification, x1.25). eCRC, early colorectal cancer; H&E,

hematoxylin and eosin; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MM, muscularis

mucosae; SM, submucosal. |

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables between two groups were

compared using the Fisher's exact test in the case of 2x2 cross

tabulations or the Chi-squared test with or without Yates'

correction as appropriate in the case of m x n cross tabulations.

Continuous variables between two groups were compared using the

Mann-Whitney U test. Continuous variables among three groups were

compared using the Kruskal-Wallis H test, with the ad-hoc test

performed by comparing two groups using the Mann-Whitney U test

with the Bonferroni correction. P-values <0.05 were considered

to indicate statistically significant differences, apart from the

Mann-Whitney U test with the Bonferroni correction, for which the

significance level was modified according to the number of groups.

Survival curves were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method and

significant differences in survival were analyzed using the

log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS

Statistics 20 (IBM Corporation).

Results

Pathological diagnosis, evaluation of

pT stage and HL

Overall, a total of 92 cases of pedunculated-type

adenocarcinoma with/without adenoma component underwent endoscopic

resection during the study period. Among these cases, 19 cases were

excluded according to the exclusion criteria. A total of 73 cases,

of which 70 cases had success with en bloc endoscopic

resection, were subjected to further analysis. Of note, 1 of the 3

cases which failed with en bloc endoscopic resection

underwent additional surgical resection. From the absence of

desmoplastic reaction, 37 cases were diagnosed as intraepithelial

carcinoma or carcinoma confined within the LPM, corresponding to

pTis by the JSCCR rule and HL0. Cases of adenocarcinoma with

desmoplastic reaction were classified as HL ≥1, which corresponds

to pTis or pT1 by the JSCCR rule. Further pathological substaging

was performed by measuring the depth of SM invasion. When the MM

could not be identified or estimated at the adenocarcinoma invasive

front (pattern A; Fig. 1B), the

depth of SM invasion was measured from the surface of the lesion.

This pattern was observed in 26 cases, which were staged as ≥pT1a

and HL ≥1. When the MM could be identified or estimated in an

original form at the adenocarcinoma invasive front, the depth of SM

invasion was measured from the lower border of the MM (pattern B;

Fig. 1C). This pattern, which

represents ≥pT1a and HL ≥1, was not observed in any of the included

cases. When a tangled MM was observed, the depth of SM invasion was

measured as the distance of invasion in the stalk beyond the

Haggitt line (pattern C; Fig. 1D).

This pattern was observed in 10 cases, which were classified as HL

≥1, corresponding to the pTis (within the Haggitt line) or ≥pT1a

(beyond the Haggitt line) stage by the JSCCR rule.

Ultimately, 47 cases were classified as pTis and 26

cases were classified as pT1b by the JSCCR rule. The pTis cases

were significantly older than the pT1b cases (P=0.040). Of the pTis

cases, 37 cases were HL0 (surveillance, 149-6,126 days; median,

2,106 days) and 10 cases were HL1-2 (surveillance, 112-2,860 days;

median, 877 days). Of the pT1b cases, 18 cases were HL1-2

(surveillance, 104-4,079 days; median, 1,050 days) and 8 cases were

HL3 (surveillance, 501-4,140 days; median, 1,306 days) (Table I).

| Table IClinicopathologic characteristics of

the included cases. |

Table I

Clinicopathologic characteristics of

the included cases.

| pT (JSCCR)/HL | pTis/HL0 | pTis/HL1-2 | pT1a/HL1-2 | pT1a/HL3 | pT1b/HL1-2 | pT1b/HL1-2 | pT1b/HL3 | pT1b/HL3 | P-value (P1/P2) |

|---|

| MM

patterna | NA | C | A and B | A, B, and C | A | B | A | B and C | NA |

| No. of cases | 37 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 8 | 0 | NA |

| Sex (M:F) | 24:13 | 7:3 | - | - | 16:2 | - | 5:3 | - | 0.280/0.446 |

| Age (median) | 35-88(71) | 46-77 (65.5) | - | - | 39-78(62) | - | 54-82(65) | - | 0.040/0.087 |

| Tumor site

(C:A:T:D:S:R:unknown) | 1:3:1:5:19:7:1 | 0:0:0:1:9:0:0 | - | - | 1:0:1:1:13:2:0 | - | 0:2:0:1:3:2:0 | - | 0.999/0.844 |

| Endoscopic en

bloc resection (yes:no) | 36:1 | 8:2 | - | - | 18:0 | - | 8:0 | - | 0.548/0.946 |

| ER status

(ER0:ER1:ERX) | 37:0:0 | 9:0:1 | - | - | 18:0:0 | - | 8:0:0 | - | NA |

| Additional surgery

(yes:no) | 0:37 | 1:9 | - | - | 3:15 | - | 6:2 | - |

<0.001/<0.001 |

| Surveillance after

endoscopic resection (median) (days) | 149-6,126

(2,106) | 112-2,860(877) | - | - | 104-4,079

(1,050) | - | 501-4,140

(1,306) | - | 0.363/0.063 |

The endoscopic resection margin status was unknown

in 1 case of pTis/HL1, which was excised in two sections, with the

patient later undergoing additional surgery. Additional surgical

resection was performed in 1, 3 and 6 cases of pTis/HL1, pT1b/HL1,

and pT1b/HL3, respectively. The incidence of additional surgery was

significantly more frequent in the pT1b cases than in the pTis

cases (P<0.001), and in the HL3 cases than in the HL0-2 cases

(4/65 vs. 6/8: P<0.001). The clinicopathological characteristics

of the the patients are summarized in Table I.

Pathological features, pT stage and HL

of the lesions

All but one of the cancer cases were well- or

moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma, with the other case

(pT1b/HL3) being mucinous adenocarcinoma. There was a significant

difference in tumor diameter between pTis (0.9-36 mm; median, 6.0

mm) and pT1b (2-40 mm; median, 10.5 mm) cases (P<0.001), and

among HL0 (0.9-14 mm; median, 4 mm), HL1-2 (2-36 mm; median, 10 mm)

and HL3 (6-40 mm; median, 10.5 mm) cases (P<0.001). The post hoc

analysis revealed that tumor diameter was significantly larger in

HL1-2 (P<0.001) and HL3 (P=0.001) cases compared with HL0 cases.

The absence of adenoma component was significantly more frequent in

pT1b cases than in pTis cases (P=0.002) and in HL3 cases than in

HL0 cases (P<0.001), although no significant difference was

observed between HL1-2 and HL0 cases (P=0.570). The depth of SM

invasion in pT1b cases, as defined by the JSCCR rule, was 2.0-15 mm

(median, 5.0 mm) in 18 HL1-2 cases and 2.0-18 mm (median, 4.5 mm)

in 8 HL3 cases. These results are summarized in Table II.

| Table IIPathological features of the

lesions. |

Table II

Pathological features of the

lesions.

| pT (JSCCR)/HL | pTis/HL0 | pTis/HL1-2 | pT1b/HL1-2 | pT1b/HL3 | P-value

(P1/P2) |

|---|

| MM pattern | NA | C | A | A | NA |

| No. of cases | 37 | 10 | 18 | 8 | NA |

| Size of cancer

(median) (mm) | 0.9-14 (4.0) | 6-36 (9.5) | 2-30 (10.5) | 6-40 (10.5) |

<0.001/<0.001 |

| Histology

(W/M:P:Muc) | 37:0:0 | 10:0:0 | 18:0:0 | 7:0:1 | NA |

| Coexisting adenoma

(yes:no) | 36:1 | 10:0 | 16:2 | 3:5 |

0.002/<0.001 |

| Depth of SM

invasion (median) (mm) | - | - | 2.0-15 (5.0) | 2.0-18 (4.5) |

NA/0.955a |

| Invasion below the

Haggitt line (median) (mm) | - | - | - | 0.3-3.0 (1.3) | NA |

The lymphatic invasion rate was marginally more

frequent in pT1b cases than in pTis cases (P=0.051), while the

venous invasion rate was significantly more frequent in pT1b cases

than in pTis cases (P=0.042). There was no significant difference

in the lymphatic invasion rate and venous invasion rate among HL0,

HL1-2 and HL3 cases, and BD between HL1-2 and HL3 cases (P=0.156,

0.632 and 0.999, respectively) (Table

III).

| Table IIIpT staging, Haggitt levels and

adverse outcomes of the lesions. |

Table III

pT staging, Haggitt levels and

adverse outcomes of the lesions.

| pT (JSCCR)/HL | pTis/HL0 | pTis/HL1-2 | pT1b/HL1-2 | pT1b/HL3 | P-value

(P1/P2) |

|---|

| MM pattern | - | C | A | A | NA |

| No. of cases | 37 | 10 | 18 | 8 | NA |

| Lymphatic invasion

(yes) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0.051/0.156 |

| Venous invasion

(yes) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.042/0.632 |

| Budding

(BD1:BD2) | - | 9:1 | 15:3 | 7:1 |

0.999/0.999a |

| Positive nodes (by

pathology) | 0/37 | 0/10 (0/1) | 0/18 (0/3) | 0/8 (0/6) | 0.999 (0.999)/NA

(NA) |

| Recurrence | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.999/0.982 |

| Recurrence-free

survival (median) (days) | 149-6,126

(2,106) | 112-2,860(748) | 104-4,079

(1,050) | 501-4,140

(1,306) | 0.338/0.059 |

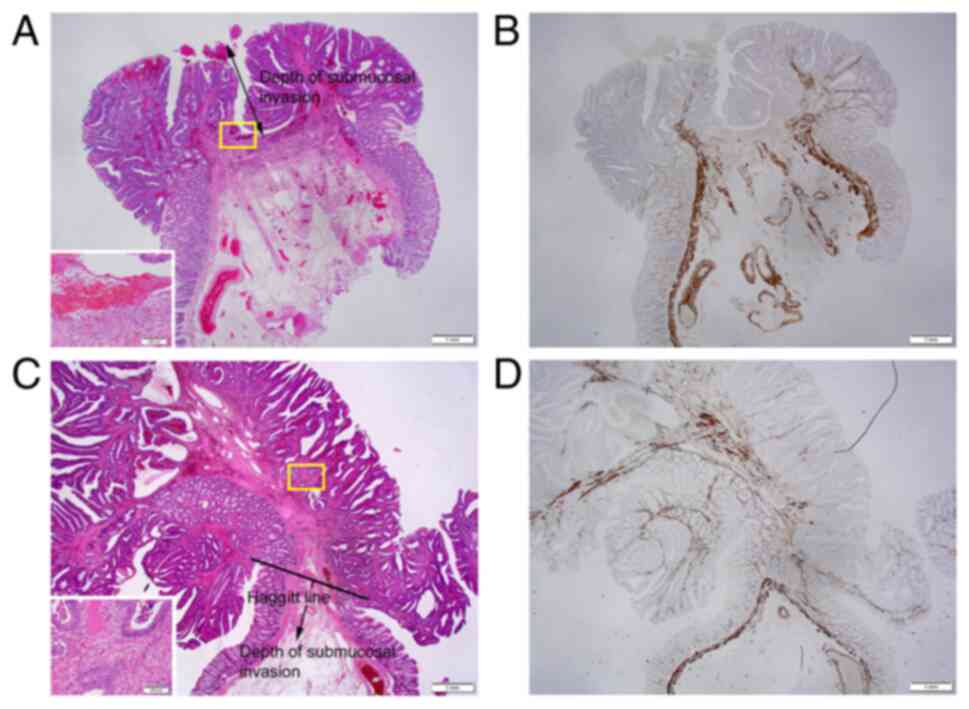

pT staging, HL and adverse

outcomes

In the present study, an adverse outcome was defined

as lymph node metastasis detected by the imaging studies and/or the

pathological inspection of surgically resected specimens and

recurrence diagnosed clinically and/or pathologically. Additional

colectomy/proctectomy with lymph node dissection following

endoscopic resection was considered in the cases with

positive/unknown resection margins, lymphovascular invasion, BD2

(5-9 buddings/x200 field), and pT1b by the JSCCR rule. Due to such

risk factors and the intentions of patients, additional surgery was

performed in 1 case of pTis and 9 cases of pT1b. The inspection of

the surgical specimens from those cases revealed no nodal

metastasis. Recurrence was not observed in any of the pTis/HL0

cases. Of note, 1 case of pTis/HL1 experienced recurrence in the

peritoneum 594 days following endoscopic en bloc resection

with negative resection margins. The stalk of the lesion was 8 mm

in diameter. The total size was 36x33 mm and the size of the

adenocarcinoma was 10x10 mm. The histological type was moderately

differentiated adenocarcinoma with MM pattern C in traditional

serrated adenoma. No lymphatic or venous invasion was seen by D2-40

and EVG staining, respectively. Muconodules were observed at the

invasive front, but the case was classified as pTis (head invasion)

by the JSCCR rule. Recurrence was not observed in any of the

pT1b/HL1-2 or pT1b/HL3 cases. The adverse outcome rates were 0, 3.6

and 0% in the HL0, HL1-2 and HL3 cases, respectively. No

significant difference was observed in the recurrence rate and the

recurrence-free survival between pTis and pT1b cases and among HL0,

HL1-2, and HL3 cases. No CRC-related deaths were reported at the

time of writing the present study. These results are presented in

Fig. 5 and summarized in Table III.

Discussion

In 2004, Kitajima et al (25) reported the results of the project

study led by the JSCCR that analyzed 865 pT1 CRC cases that had

been surgically resected. Lymph node metastasis was found in 87

cases (10.1%), comprising 10 (7.1%) of the 141 pedunculated lesions

and 77 (10.6%) of the 724 non-pedunculated lesions. Lymph node

metastasis was not observed in the pedunculated lesions with head

invasion and stalk invasion presenting an SM depth <3,000 µm if

lymphatic invasion was negative. The vertical distance from the

Haggitt line to the deepest portion of invasion was designated as

the SM depth in the pedunculated lesion. The nodal metastasis rate

in the non-pedunculated lesions was 0% (0/123) when SM invasion was

<1,000 µm and 12.8% (77/601) when SM invasion was ≥1,000 µm

(25). From these results, the JSCCR

guidelines 2005 for the treatment of CRC (26) stated that additional surgery

following endoscopic resection of CRC should be considered when any

of the following conditions was noted: i) Positive SM vertical

margin; ii) SM invasion of ≥1,000 µm; iii) positive lymphatic

and/or venous invasion; and iv) poorly differentiated

adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma. In these guidelines,

unlike in the study by Kitajima et al (25), the depth of SM invasion was

determined to be measured from the lower MM border when the MM

could be identified or estimated and from the lesion's surface when

the MM could not be identified or estimated, irrespective of the

macroscopic type. In addition, the SM depth was to be measured from

the reference line to the deepest portion of invasion in MM-tangled

pedunculated lesions (26).

Consequently, some cases with head invasion may be evaluated as

pT1b with deep SM invasion, making them candidates for additional

surgery.

In the present study, strict pathological diagnostic

criteria were applied for pT staging. In pedunculated lesions,

differentiation was required for the findings of SM localization of

normal and adenoma glands, specifically, SM misplacement and SM

pseudoinvasion. These phenomena may cause pT overstaging and result

in underestimating the prognosis of pT1 carcinoma cases. The

present study thus rigorously evaluated nuclear atypia as

malignancy and diagnosed SM invasion only when desmoplastic

reaction was observed at the invasive front, as cancer invasion in

the LPM usually does not cause desmoplastic reaction (22). Distinction between desmoplastic

reaction and a dissected or fragmented MM is usually not difficult

for experienced pathologists. However, EVG staining and desmin IHC

assays were conducted, as appropriate, in difficult cases.

Reportedly, reproducibility is not high among pathologists when

distinguishing between MM-tangled and non-tangled cases

(coincidence rate: κ value of 0.55) (27). Desmin IHC staining was used to help

distinguish between the two.

Following these pathological evaluations, the cases

included in the present study were classified as follows: 37

pTis/HL0 cases, 10 pTis/HL1-2 cases, 18 pT1b/HL1−2 cases, and eight

pT1b/HL3 cases. As the adenocarcinoma size increased, the pT stage

and HL also increased, while the rate of coexisting adenoma

decreased. As was expected, no adverse outcomes were found in the

pTis/HL0 cases. Notably, no adverse outcome was observed in any of

the 26 pT1b/HL1-3 cases, although the JSCCR guidelines assumed

lymph node metastasis in ~10% of the endoscopically resected pT1b

eCRC cases (26). Herein, the depth

of SM invasion in the pT1b/HL1−2 and pT1b/HL3 cases ranged from

2.0-15 mm (median, 5.0 mm) and 2.0-18 mm (median, 4.5 mm),

respectively, far exceeding the thickness of the normal colorectal

wall (~3.3 mm). These data suggested that pT1b substaging using the

JSCCR rule may not be useful as a tool for determining the need for

additional surgery.

The latest JSCCR guidelines 2019 for the treatment

of CRC weakly recommends additional bowel resection with lymph node

dissection for pT1b pedunculated lesions, although other factors,

such as histological subtype, lymphovascular invasion, high BD rate

(BD2/3), and the wishes of patients, need to also be taken into

consideration (9). Since the JSCCR

guidelines 2005, a limited number of studies have validated the

prognostic utility of the pT1b substaging system in the

pedunculated lesions. In 2004, Ueno et al (11) measured the SM depth in the same

manner as the JSCCR rule and investigated the association of SM

depth with lymph node metastasis. However, they did not perform pT

staging, combining the data of pedunculated and non-pedunculated

lesions and analyzing them as one dataset. In 2016, Asayama et

al (28) solely reported the

prognostic significance of pT1b substaging using the present JSCCR

rule. Adverse outcomes were also very rare in their cases. The

lymph node metastasis rate was 3.9%, while the recurrence rate was

1.3% (Table IV). Their data also

suggested that pT1b substaging using the JSCCR rule may not be

useful as a tool for determining the need for additional surgery.

Furthermore, accurate pathological pT staging is somewhat

difficult. SM misplacement and pseudoinvasion of neoplastic glands

may result in overstaging. Additionally, pathologists often

disagree on whether the MM is tangled or not. Therefore, we propose

to reconsider the definition of deep SM invasion (pT1b) in

pedunculated lesions in the JSCCR rule.

| Table IVAdverse outcomes of JSCCR pT1

pedunculated-type lesions in the study by Asayama et al

(28) and the present study. |

Table IV

Adverse outcomes of JSCCR pT1

pedunculated-type lesions in the study by Asayama et al

(28) and the present study.

| | Rate of LN

metastasis (%) | Recurrence rate

(%) | |

|---|

| Author(s), year of

publication | pT1a | pT1b | pT1a | pT1b | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Asayama et

al, 2016 | 1/100 (1.0) | 3/76 (3.9) | 0/100 (0.0) | 1/76 (1.3) | (28) |

| Present study | - | 0/26 (0.0) | - | 0/26 (0.0) | |

| Total (%) | 1/100 (1.0) | 3/102 (2.9) | 0/100 (0.0) | 1/102 (1.0) | |

In 1985, Haggitt et al (13) reported that no nodal metastasis was

observed in 36 cases of pedunculated CRC with HL1-3, while one HL3

patient succumbed due to the disease. Several researchers have

since reported the rates of adverse outcomes, such as lymph node

metastasis, recurrence and disease-related mortality, in

pedunculated eCRC cases that underwent surgical or endoscopical

resection (11,13,25,28-30)

(Table V). According to these

previous studies and the present study, the lymph node metastasis

rates were 2.3 and 7.3% in HL1-2 and HL3 cases, respectively, while

the recurrence rates were 0.3 and 0.9% in HL1-2 and HL3,

respectively. Although Kitajima et al (25) emphasized the importance of vascular

invasion as a criterion of the need for additional surgery, Matsuda

et al (29) reported that the

incidence of nodal metastasis was 0 (0%) of 101 cases with head

invasion, in which lymphatic and/or venous invasion was observed in

29 (28.7%) cases. They thereby concluded that pedunculated invasive

eCRC can be managed by endoscopic treatment alone. These studies

suggest that additional surgery may not be necessary for

pedunculated CRC cases with HL1-2, irrespective of their vascular

invasion status. Although there are a limited number of similar

studies from Europe and the USA, the latest European (31) and American (32) guidelines suggest that only HL4 is a

risk factor of lymph node metastasis.

| Table VAdverse outcomes of pedunculated-type

lesions according to the Haggitt level reported in the

literature. |

Table V

Adverse outcomes of pedunculated-type

lesions according to the Haggitt level reported in the

literature.

| | Rate of LN

metastasis (%) | Recurrence rate

(%) | Dead of disease

(%) | |

|---|

| Author(s), year of

publication | HL0 | HL1-2 | HL3 | HL0 | HL1-2 | HL3 | HL0 | HL1-2 | HL3 | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Haggitt et

al, 1985 | 0/18 (0.0) | 0/9 (0.0) | 0/4 (0.0) | - | - | - | 0/65 (0.0) | 0/26 (0.0) | 1/10 (10.0) | (13) |

| Ueno et al,

2004 | - | 0/42 (0.0) | 6/24 (25.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - | (11) |

| Kitajima et

al, 2004 | - | 3/53 (5.7) | 7/88 (8.0) | - | - | - | - | - | - | (25) |

| Matsuda et

al, 2011 | - | 0/101 (0.0) | 8/129 (6.2) | - | 0/219 (0.0) | 1/121 (0.8) | - | - | - | (29) |

| Asayama et

al, 2016 | - | 1/78 (1.3) | 3/98 (3.1) | - | 0/78 (0.0) | 1/98 (1.0) | - | 0/78 (0.0) | 0/98 (0.0) | (28) |

| Kimura et

al, 2016 | - | 4/30 (13.3) | 5/46 (10.9) | - | - | - | - | - | - | (30) |

| Present study | 0/37 (0.0) | 0/28 (0.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | 0/37 (0.0) | 1/28 (0.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | 0/37 (0.0) | 0/28 (0.0) | 0/8 (0.0) | |

| Total | 0/55 (0.0) | 8/341 (2.3) | 29/397 (7.3) | 0/37 (0.0) | 1/325 (0.3) | 2/227 (0.9) | 0/102 (0.0) | 0/132 (0.0) | 1/116 (0.9) | |

In the present study, notably, recurrence was

observed in 1 case of pTis/HL1 without lymphovascular invasion by

pathological inspection. Both pT staging by the JSCCR rule and the

Haggitt classification were unable to help predict recurrence in

this case, emphasizing that there is no method which can be used to

completely predict adverse outcomes. The estimated risk level by

pathological inspection can only be used as a basis for deciding

whether to perform additional resections. Despite its shortcomings,

it can be considered that the Haggitt classification may be more

useful than the JSCCR rule as it can help avoid any unnecessary

additional surgical procedures.

Finally, there are some interesting studies on the

SM depth as a prognostic factor in eCRC. According to the study

‘The stratification of risk factors for the metastasis of pT1b SM

cancer (SM invasion more than 1,000 µm)’ by JSCCR (33), the incidence of lymph node metastasis

was 1.4% in cases wherein only SM invasion depth did not satisfy

the criteria for radical cure and where no other risk factors for

metastasis were observed. On the other hand, even if surgery for T1

eCRC was carried out at first, the incidence of metastatic

recurrence was 1.5% for colon and 4.2% for rectum (34). These studies suggest that surgery

performed due to the presence of only deep SM invasion may have

only restricted merit on prognosis.

The present study has some limitations. Firstly, the

present study was retrospective and was performed at two

institutions in the northern Kanto Region in Japan. Therefore, the

numbers of events were small, with potential ethnic bias. Secondly,

cases that were endoscopically resected were included, but those

which underwent surgery without endoscopic resection were not.

Therefore, the lymph node metastasis rate may have been

underestimated.

In conclusion, using the JSCCR rule to evaluate

pedunculated eCRC may cause pT1 overstaging and unnecessary

additional surgery. Other reference lines for measuring the SM

depth, such as the Haggitt line and MM of the underlying bowel

wall, should be reconsidered. Otherwise, pT should be excluded from

the risk assessment when considering additional surgery in

pedunculated eCRC cases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

YI, YO, TY and MI conceived and designed the study.

YI and SS performed the pathological diagnosis. YI analyzed the

data and wrote the manuscript. YO, TT, TY, HS and MI acquired the

clinicopathological data. YI, YO, and MI confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors critically revised the manuscript,

and have read and approved the final version to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Ethical

Committees of Ota Memorial Hospital (Ota, Japan; approval no.

OR24029) and International University of Health and Welfare

(Nasushiobara, Japan; approval no. FK-94). Due to the retrospective

study design and anonymization of data, consent to participate was

not necessary.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Morson BC, Whiteway JE, Jones EA, Macrae

FA and Williams CB: Histopathology and prognosis of malignant

colorectal polyps treated by endoscopic polypectomy. Gut.

25:437–444. 1984.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Fujimori T, Kawamata H and Kashida H:

Precancerous lesion of the colorectum. J Gastroenterol. 36:587–594.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Cooper HS: Surgical pathology of

endoscopically removed malignant polyps of the colon and rectum. Am

J Surg Pathol. 7:613–623. 1983.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kyzer S, Bégin LR, Gordon PH and Mitmaker

B: The care of patients with colorectal polyps that contain

invasive adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 70:2044–2050. 1992.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Minamoto T, Mai M, Ogino T, Sawaguchi K,

Ohta T, Fujimoto T and Takahashi Y: Early invasive colorectal

carcinomas metastatic to the lymph node with attention to their

nonpolypoid development. Am J Gastroenterol. 88:1035–1039.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Tanaka S, Haruma K, Teixeira CR, Tatsuta

S, Ohtsu N, Hiraga Y, Yoshihara M, Sumii K, Kajiyama G and

Shimamoto F: Endoscopic treatment of submucosal invasive colorectal

carcinoma with special reference to risk factors for lymph node

metastasis. J Gastroenterol. 30:710–717. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon

and Rectum. Japanese Classification of Colorectal, Appendiceal, and

Anal Carcinoma: The 3d English Edition [Secondary Publication]. J

Anus Rectum Colon. 3:175–195. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Participants in the Paris Workshop. The

Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions:

Esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002.

Gastrointest Endosc. 58:S3–43. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hashiguchi Y, Muro K, Saito Y, Ito Y,

Ajioka Y, Hamaguchi T, Hasegawa K, Hotta K, Ishida H, Ishiguro M,

et al: Japanese society for cancer of the colon and rectum (JSCCR)

guidelines 2019 for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Int J Clin

Oncol. 25:1–42. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Berman JM, Cheung RJ and Weinberg DS:

Surveillance after colorectal cancer resection. Lancet.

355:395–399. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ueno H, Mochizuki H, Hashiguchi Y,

Shimazaki H, Aida S, Hase K, Matsukuma S, Kanai T, Kurihara H,

Ozawa K, et al: Risk factors for an adverse outcome in early

invasive colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 127:385–394.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Tanaka S, Haruma K, Oh-E H, Nagata S,

Hirota Y, Furudoi A, Amioka T, Kitadai Y, Yoshihara M and Shimamoto

F: Conditions of curability after endoscopic resection for

colorectal carcinoma with submucosally massive invasion. Oncol Rep.

7:783–788. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Haggitt RC, Glotzbach RE, Soffer EE and

Wruble LD: Prognostic factors in colorectal carcinomas arising in

adenomas: Implications for lesions removed by endoscopic

polypectomy. Gastroenterology. 89:328–336. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee.

Fisher DA, Shergill AK, Early DS, Acosta RD, Chandrasekhara V,

Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Evans JA, Fanelli RD, et al: Role of

endoscopy in the staging and management of colorectal cancer.

Gastrointest Endosc. 78:8–12. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Pimentel-Nunes P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Ponchon

T, Repici A, Vieth M, De Ceglie A, Amato A, Berr F, Bhandari P,

Bialek A, et al: Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European society

of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy.

7:829–854. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Resch A and Langner C: Risk assessment in

early colorectal cancer: Histological and molecular markers. Dig

Dis. 33:77–85. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Backes Y, Elias SG, Groen JN, Schwartz MP,

Wolfhagen FHJ, Geesing JMJ, Ter Borg F, van Bergeijk J, Spanier

BWM, de Vos Tot Nederveen Cappel WH, et al: Histologic factors

associated with need for surgery in patients with pedunculated T1

colorectal carcinomas. Gastroenterology. 154:1647–1659.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cubiella J, González A, Almazán R,

Rodríguez-Camacho E, Rodiles JF, Ferreiro CD, Sandoval CT, Gómez

CS, de Vicente Bielza N, Lorenzo IP, et al: pT1 colorectal cancer

detected in a colorectal cancer mass screening program: Treatment

and factors associated with residual and extraluminal disease.

Cancers (Basel). 12(2530)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Knoblauch M, Kühn F, von

Ehrlich-Treuenstätt V, Werner J and Renz BW: Diagnostic and

therapeutic management of early colorectal cancer. Visc Med.

39:10–16. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Nagtegaal ID, Arends MJ and Salto-Tellez

M: Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. In: WHO classification of

tumours/Digestive system tumours. 5th edition. WHO Classification

of Tumours Editorial Board. IARC Press, Lyon, pp177-187, 2019.

|

|

21

|

Union for International Cancer Control

(UICC): Colon and Tectum. In: TNM classification of malignant

tumours. 8th edition. Brierley JD, Gospodarowicz MK and Wittekind C

(eds). Wiley Blackwell, Oxford, pp84-88, 2017.

|

|

22

|

Ohno K, Fujimori T, Okamoto Y, Ichikawa K,

Yamaguchi T, Imura J, Tomita S and Mitomi H: Diagnosis of

desmoplastic reaction by immunohistochemical analysis, in biopsy

specimens of early colorectal carcinoma, is efficacious in

estimating the depth of invasion. Int J Mol Sci. 14:13129–13136.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gascard P and Tlsty TD:

Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts: Orchestrating the composition of

malignancy. Genes Dev. 30:1002–1019. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Ueno H, Kajiwara Y, Ajioka Y, Sugai T,

Sekine S, Ishiguro M, Takashima A and Kanemitsu Y:

Histopathological atlas of desmoplastic reaction characterization

in colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 51:1004–1012.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kitajima K, Fujimori T, Fujii S, Takeda J,

Ohkura Y, Kawamata H, Kumamoto T, Ishiguro S, Kato Y, Shimoda T, et

al: Correlations between lymph node metastasis and depth of

submucosal invasion in submucosal invasive colorectal carcinoma: A

Japanese collaborative study. J Gastroenterol. 39:534–543.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Japanese Society for Cancer of the Colon

and Rectum (JSCCR): JSCCR guidelines 2005 for the treatment of

colorectal cancer (In Japanese). https://www.jsccr.jp/guideline/2005/particular.html.

Accessed on August 16, 2024.

|

|

27

|

Fukuzawa M: Management of early

pedunculated colorectal cancer. Gastroenterol Endosc. 64:2255–2267.

2022.(In Japanese).

|

|

28

|

Asayama N, Oka S, Tanaka S, Nagata S,

Furudoi A, Kuwai T, Onogawa S, Tamura T, Kanao H, Hiraga Y, et al:

Long-term outcomes after treatment for pedunculated-type T1

colorectal carcinoma: A multicenter retrospective study. J

Gastroenterol. 51:702–710. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Matsuda T, Fukuzawa M, Uraoka T, Nishi M,

Yamaguchi Y, Kobayashi N, Ikematsu H, Saito Y, Nakajima T, Fujii T,

et al: Risk of lymph node metastasis in patients with pedunculated

type early invasive colorectal cancer: A retrospective multicenter

study. Cancer Sci. 102:1693–1697. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Kimura YJ, Kudo S, Miyachi H, Ichimasa K,

Kouyama Y, Misawa M, Sato Y, Matsudaira S, Oikawa H, Hisayuki T, et

al: ‘Head invasion’ is not a metastasis-free condition in

pedunculated T1 colorectal carcinoma based on the precise

histopathological assessment. Digestion. 94:166–175.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Hassan C, Wysocki PT, Fuccio L,

Seufferlein T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Brandão C, Regula J, Frazzoni L,

Pellise M, Alfieri S, et al: Endoscopic surveillance after surgical

or endoscopic resection for colorectal cancer: European society of

gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society of digestive

oncology (ESDO) Guideline. Endoscopy. 51:266–277. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Shaukat A, Kaltenbach T, Dominitz JA,

Robertson DJ, Anderson JC, Cruise M, Burke CA, Gupta S, Lieberman

D, Syngal S and Rex DK: Endoscopic recognition and management

strategies for malignant colorectal polyps: Recommendations of the

US multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology.

159:1916–1934. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Tanaka S, Kashida H, Saito Y, Yahagi N,

Yamano H, Saito S, Hisabe T, Yao T, Watanabe M, Yoshida M, et al:

Japan gastroenterological endoscopy society guidelines for

colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection/endoscopic mucosal

resection. Dig Endosc. 32:219–239. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Kobayashi H, Mochizuki H, Morita T, Kotake

K, Teramoto T, Kameoka S, Saito Y, Takahashi K, Hase K, Oya M, et

al: Characteristics of recurrence after curative resection for T1

colorectal cancer: Japanese multicenter study. J Gastroenterol.

46:203–211. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|